Text

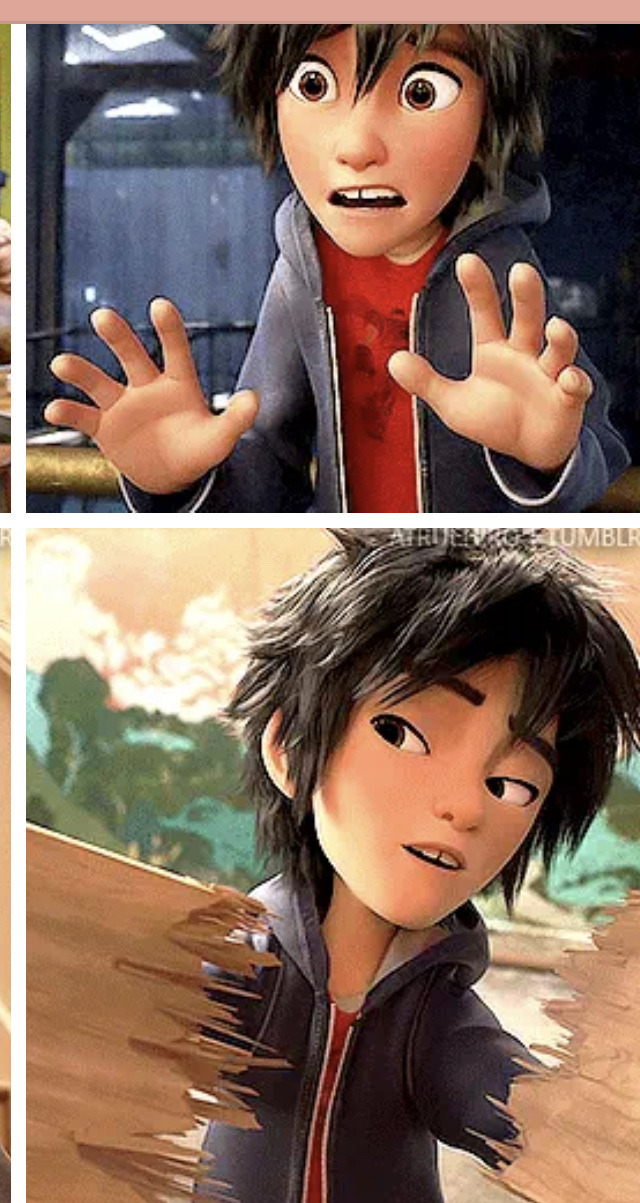

GUYS GUYS ITS HERE!!!

Lets fucking GOOOOOO

You gotta wait for the next part! Its gonna be hilarious!

961 notes

·

View notes

Text

Can I change your mind about the last building (New York)?🌝

just learned about a building in london that is so poorly designed it becomes a death ray that melts cars and creates a downdraft effect with wind so powerful that it knocks full grown adults to the ground

195K notes

·

View notes

Text

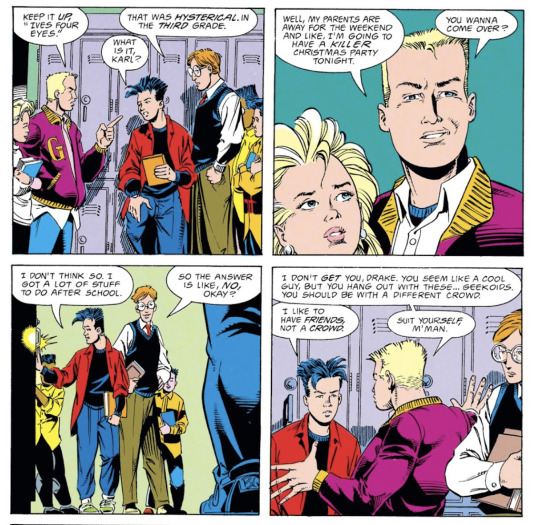

In his highschool days they kept trying to make out like Tim was someone all the guys wanted to hang out with but out of context it looks like Tim’s getting asked out like every time and I find that a little funny cause Tim wouldn’t have noticed either way

2K notes

·

View notes

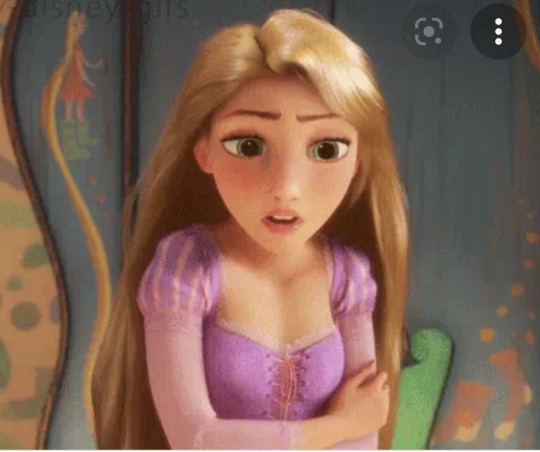

Photo

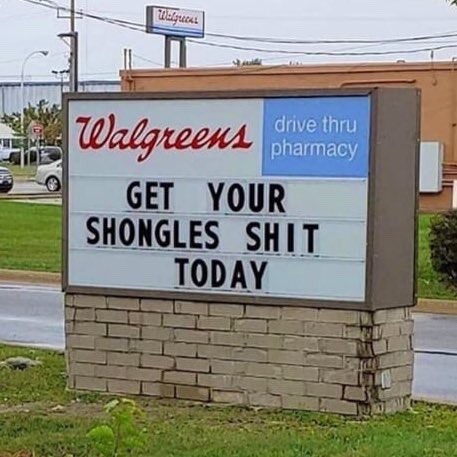

My poor little heart can’t take this, I love them so much

It was a good episode!

#good lord take me now#Eric#is a conniving simp to the very end and Kyle will always be angry#how do I fix my rotten brain to compute love in any other way#irrepressibly damaged and longing for that kind of connection#kyle broflovski#eric cartman#south park#butters

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

God i love my 90s babies, they run through my veins

My sister sent me this photo today with zero context and I laughed so hard I couldn’t breathe

120K notes

·

View notes

Text

kill me and don’t bother to resurrect me until I can watch the SP series animated like this and more Eric obsessively taunting a psychopathically angry Kyle

*bonk sfx*

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

The main four SP boys are so funny and i wish more people appreciated how funny the dynamic and history between specifically the four of them are.

They're the coolest kids in school and everyone wanted to be their friend. No one likes them. When one died (semi)permanently, they ran a The Bachelor-type contest to pick a new bestie. They forced a kid to dress like their dead friend. The vibes were still off though so the dead kid came back. They're eight years old. They're ten years old. They're 9 years old. One of them has an alcohol addiction and depression. They've all seen each other naked. When one of them got herpes, he immediately passed it to the other three. These two things are unrelated. Three of them know the other is a psychopath who will kill people who get in his way and they're just like "wtvr". They hate each other more than anything. They cannot stop being best friends or it'll ruin the future of America. They would kill or die for each other. At 50 years old they still have hissy fits like children out in public over an argument none of them even remembers having. They're obsessed with each other. One of them gave another AIDS. They make each other so much worse for being involved in their lives. There is no low any of them could stoop to that the others would find it impossible to be their friend still.

When Chef said that they're friends "whether you like [each other] or not" he wasn't kidding. Its literally inescapable and thats so funny to their dynamic, why would you ever try to change that lol.

704 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Importance of The Unlikable Heroine

I’ve always had this tendency to apologize for everything—even things that aren’t my fault, things that actually hurt me or were wrongs against me.

It’s become automatic, a compulsion I am constantly fighting. Even more disturbingly, I’ve discovered in conversations with my female friends that I’m not alone in feeling this impulse to be pleasant, to apologize needlessly, to resist showing anger.

After all, if you’re a woman and you demonstrate anger, you’re a bitch, a harpy, a shrew. You’re told to smile more because you will look prettier; you’re told to calm down even when whatever anger or otherwise “unseemly” emotion you’re experiencing is perfectly justified.

If you don’t, no one will like you, and certainly no one will love you.

I’m not sure when this apologetic tendency of mine emerged. Maybe it began during childhood; maybe the influence of social gender expectations had already begun to affect me on a subconscious level. But if I had to guess, I would assume it emerged later, when I became aware through advertisements, media, and various unquantifiable social pressures of what a girl should be—how to act, how to dress, what to say, what emotions are okay and what emotions are not.

Essentially, I became aware of what I should do, as a girl, to be liked, and of how desperate I should be to achieve that state.

Being liked would be the pinnacle of my personal achievement. I could accomplish things, sure—make good grades, go to a good school, have a stellar career. But would I be liked during all of this? That was the important thing.

It angers me that I still struggle with this. It angers me that even though I’m an intelligent, accomplished adult woman, I still experience automatic pangs of inadequacy and shame when I perceive myself to have somehow disappointed these unfair expectations. I can’t always seem to get my emotions under control, and yet I must—because sometimes those emotions are angry or unpleasant or, God forbid, unattractive, and therefore will inconvenience someone or make someone uncomfortable.

Maybe that’s why, in my fiction—both the stories I read and the stories I write—I’ve always gravitated toward what some might call “unlikable” heroines.

It’s difficult to define “unlikability”; the term itself is nebulous. If you asked ten different people to define unlikability, you would probably receive ten different answers. In fact, I hesitated to write this piece simply because art is not a thing that should be quantified, or shoved into “likable” and “unlikable” components.

But then there are those pangs of mine, that urge to apologize for not being the right kind of woman. Insidious expectations lurk out there for our girls—both real and fictional—to be demure and pleasant, to wilt instead of rally, to smile and apologize and hide their anger so they don’t upset the social construct—even when such anger would be expected, excused, even applauded, in their male counterparts.

So for my purposes here, I’ll define a “likable heroine” as one who is unobjectionable. She doesn’t provoke us or challenge our expectations. She is flawed, but not offensively. She doesn’t make us question whether or not we should like her, or what it says about us that we do.

Let me be clear: There is nothing wrong with these “likable” heroines. I can think of plenty such literary heroines whom I adore:

Fire in Kristin Cashore’s Fire. Karou in Laini Taylor’s Daughter of Smoke and Bone series. Jo March in Little Women. Lizzie Bennet in Pride and Prejudice. The Penderwick sisters in Jeanne Birdsall’s delightful Penderwicks series. Arya (at least, in the early books) in A Song of Ice and Fire. Sarah from A Little Princess. Meg Murry from A Wrinkle in Time. Matilda in Roald Dahl’s classic book of the same name.

These heroines are easy to love and root for. They have our loyalty on the first page, and that never wavers. We expect to like them, for them to be pleasant, and they are. Even their occasional unpleasantness, as in the case of temperamental Jo March, is endearing.

What, then, about the “unlikable” heroines?

These are the “difficult” characters. They demand our love but they won’t make it easy. The unlikable heroine provokes us. She is murky and muddled. We don’t always understand her. She may not flaunt her flaws but she won’t deny them. She experiences moral dilemmas, and most of the time recognizes when she has done something wrong, but in the meantime she will let herself be angry, and it isn’t endearing, cute, or fleeting. It is mighty and it is terrifying. It puts her at odds with her surroundings, and it isn’t always easy for readers to swallow.

She isn’t always courageous. She may not be conventionally strong; her strength may be difficult to see. She doesn’t always stand up for herself, or for what is right. She is not always nice. She is a hellion, a harpy, a bitch, a shrew, a whiner, a crybaby, a coward. She lies even to herself.

In other words, she fails to walk the fine line we have drawn for our heroines, the narrow parameters in which a heroine must exist to achieve that elusive “likability”:

Nice, but not too nice.

Badass, but not too badass, because that’s threatening.

Strong, but ultimately pliable.

(And, I would add, these parameters seldom exist for heroes, who enjoy the limitless freedoms of full personhood, flaws and all, for which they are seldom deemed “unlikable” but rather lauded.)

Who is this “unlikable” heroine?

She is Amy March from Little Women. She is Briony from Ian McEwan’s Atonement. Katsa from Kristin Cashore’s Graceling. Jane Austen’s Emma Woodhouse. Sansa from A Song of Ice and Fire. Mary from The Secret Garden. She is Philip Pullman’s Lyra, and C. S. Lewis’s Susan, and Rowling’s first-year Hermione Granger. She is Katniss Everdeen. She is Scarlett O’Hara.

These characters fascinate me. They are arrogant and violent, reckless and selfish. They are liars and they are resentful and they are brash. They are shallow, not always kind. They may be aggressive, or not aggressive enough; the parameters in which a female character can acceptably display strength are broadening, but still dishearteningly narrow. I admire how the above characters embrace such “unbecoming” traits (traits, I must point out, that would not be noteworthy in a man; they would simply be accepted as part of who he is, no questions asked).

These characters learn from their mistakes, and they grow and change, but at the end of the day, they can look at themselves in the mirror and proclaim, “Here I am. This is me. You may not always like me—I may not always like me—but I will not be someone else because you say I should be. I will not lose myself to your expectations. I will not become someone else just to be liked.”

When I wrote my first novel, The Cavendish Home for Boys and Girls, I knew some readers would have a hard time stomaching the character of Victoria. She is selfish, arrogant, judgmental, rigid, and sometimes cruel. Even at the end of the novel, by which point she has evolved tremendously, she isn’t particularly likable, if we go with the above definition.

I had similar concerns about the heroine of my second novel, The Year of Shadows. Olivia Stellatella is a moody twelve-year-old who isolates herself from her peers at school, from her father, from everything that could hurt her. Her circumstances at the beginning of the novel are inarguably terrible: Her mother abandoned their family several months prior, with no explanation. Her father conducts the city orchestra, which is on the verge of bankruptcy. He neglects his daughter in favor of saving his livelihood. He sells their house and moves them into the symphony hall’s storage rooms, where Olivia sleeps on a cot and lives out of a suitcase. She calls him The Maestro, refusing to call him Dad. She hates him. She blames him for her mother leaving.

Olivia is angry and confused. She is sarcastic, disrespectful, and she tells her father exactly what she thinks of him. She lashes out at everyone, even the people who want to help her. Sometimes her anger blinds her, and she must learn how to recognize that.

I knew Olivia’s anger would be hard for some readers to understand, or that they would understand but still not like her.

This frightened me.

As a new author, the prospect of writing these heroines—these selfish, angry, difficult heroines—was a daunting one. What if no one liked them? What if, by extension, no one liked me?

But I’ve allowed the desire to be liked thwart me too many times. The fact that I nearly let my fear discourage me from telling the stories of these two “unlikable” girls showed me just how important it was to tell their stories.

I know my friends and I aren’t the only women who feel that constant urge to apologize, to demur, to rein in anger and mutate it into something more socially acceptable.

I know there are girls out there who, like me at age twelve—like Olivia, like Victoria—are angry or arrogant or confused, and don’t know how to handle it. They see likable girls everywhere—on the television, in movies, in books—and they accordingly paste on strained smiles and feel ashamed of their unladylike grumpiness and ambition, their unseemly aggression.

I want these girls to read about Victoria and Olivia—and Scarlett, Amy, Lyra, Briony—and realize there is more to being a girl than being liked. There is more to womanhood than smiling and apologizing and hiding those darker emotions.

I want them to sift through the vast sea of likable heroines in their libraries and find more heroines who are not always happy, not always pleasant, not always good. Heroines who make terrible decisions. Heroines who are hungry and ambitious, petty and vengeful, cowardly and callous and selfish and gullible and unabashedly sensual and hateful and cunning. Heroines who don’t always act particularly heroic, and don’t feel the need to, and still accept themselves at the end of the day regardless.

Maybe the more we write about heroines like this, the less susceptible our girl readers will be to the culture of apology that surrounds them.

Maybe they will grow up to be stronger than we are, more confident than we are. Maybe they will grow up in a world brimming with increasingly complex ideas about what it means to be a heroine, a woman, a person.

Maybe they will be “unlikable” and never even think of apologizing for it.

22K notes

·

View notes

Text

This is fucking incredible. I struggled to wrap my head around Kyle’s inconsistencies— I believe he has the strongest empathy of the boys, but sometimes his unintentional callousness was confusing to me. I couldn’t figure it out. I actually attributed it to emotional-unavailability, where he cares but solidly puts himself first, but that didn’t always hold up, because he’s susceptible to manipulation and is often sucked into/consumed by the problems of others.

Anyways, what I mean to say is that this is amazingly done. Love it!

Also, just watched the Vaccine Special (which had me going down the rabbit hole of Kyle’s parents). Why the hell aren’t people talking about how shitty Kyle’s parents (especially Gerald) is? The scene where he purposely blackmails and emotionally manipulates his nine-year-old kid fuckin hurt. (“Hey…and don’t kill your mom.”) It was seriously off-putting and shocks me that I see a lot of positive commentary about Gerald’s behavior (maybe in contrast to Stan, Kenny, and Eric’s basketcase parents).

Kyle's attitude toward mental health

Okay, I love Kyle to death, but I want to talk about one of his biggest apparent flaws in the show. I say 'apparent' because I think there is an underlying reason why his attitude about mental health seems less than ideal, but before I get into that I want to highlight some of the moments in which he reacts to mental health struggles.

The first time he's kind of confronted with someone who's really going through it is in Cartman's Mom is a Dirty Slut when he, Stan, and Kenny spy on Cartman having a tea party with his toys. Kyle's first instinct is to go make fun of him, and Stan says "No, dude. This look really serious. I think we'd better get help.", to which Kyle responds with a confused/surprised "Really?". After that, Kyle is the first one to suggest to Mr. Mackey that there's something wrong with Cartman, showing that he's on board with Stan's concerns - he just wasn't able to identify that there was something wrong on his own, initially. This, I think, is an example of Kyle being consistently shown, especially in the early seasons, to be a little more immature than the other boys in the sense that he doesn't understand adult subjects or themes, has interests that are more childish than the other boys, and is just generally a little behind. He's able to empathize with Cartman, at least momentarily, only after it's pointed out to him that there's probably something going on.

Later, in Raisins, Kyle is faced with Stan's heartbreak over Wendy and just... really doesn't get it. He wants to help, but tries things that only address the surface issue (Stan wants a girlfriend) rather than the actual issue (Stan is heartbroken over Wendy specifically). Kyle has only experienced one brief, meaningless crush at this point, and so he can't identify with Stan's struggle. He thinks that moving on should be easy. Stan's inability to move on, and his subsequent attachment to the goth kids, angers Kyle because he doesn't understand what's going on. His response to Stan's heartbreak and the goth kids' general attitude towards life is to just get over it, citing that there are other people in the world who have it much worse than them and know what "real pain" is. He then tells Stan to stop feeling sorry for himself, which Stan refuses.

The next time Kyle is confronted with a major mental health issue is when Stan starts hoarding in Insheeption. It's implied, by the fact that Wendy is the one to initially bring the issue up, that Kyle either hasn't noticed it yet or hasn't realized that there's something wrong. Like the example of Cartman's tea party, Kyle needs to be told there's an issue because he just doesn't know enough about psychology and mental health to recognize it on his own. But his response in this case, once he sees Stan's reaction to the hoarding expert, is to suggest that Stan talk to Mr. Mackey. At this point he's aware of the resources available to them and is able to understand that there's something wrong that needs to be addressed by an adult. At the end, Kyle is also able to point out that Stan's problem wasn't actually resolved and there must be something in his past that he's not dealing with, which I think shows growth in his understanding. I wouldn't be surprised if he spent the whole episode off screen, researching hoarding on his own time.

Then, obviously, there's Ass Burgers. When confronted by Wendy, Kyle says of Stan's depression, "I've tried, Wendy. I've called him, I've been to his house. But since his diagnosis, all he's done is gotten worse." This demonstrates that Kyle is 1) taking Stan's diagnosis seriously, even if we all as viewers know it's the wrong diagnosis and 2) that he's been actively trying to be there for Stan and knows it's not helping. He then says, "I can't keep doing it, Wendy. I know he has an illness, but goddamn, it's like being around a black hole that just sucks the life out of everything." And then, "All his negativity is starting to make me depressed. I have to let him go. And whatever happens next, I'm going to embrace with a totally positive attitude." Kyle has tried to be there for Stan in between YGO and AB, but Stan's depression is having a negative impact on Kyle's own mental health. Kyle's choice here isn't the wrong one - he's putting up a boundary to protect himself. It's not that he's unsympathetic to Stan's problem, in fact he's taking it very seriously, it's that he recognizes that HE can't personally help and continuing to try to be there for Stan is making him depressed. Again he has a very "just get over it" attitude, but this time it's not directed at Stan, it's directed at himself. He's telling Wendy that he has to get over his own feelings and force himself to have a positive attitude.

He again takes this "positive attitude" approach in the Mysterion trilogy when Kenny is clearly in distress and trying to explain his curse to the boys. Kyle's attempt to comfort him involves telling him it's actually pretty cool to not be able to die. This obviously doesn't go over well with Kenny, who just wants to be understood. I don't think Kyle is trying to be dismissive, I think he really thinks he's helping by trying to get Kenny to change his perspective, but it comes off the wrong way.

In Buddha Box, he says, "I got news for you, Cartman! Everyone has anxiety! Everyone gets nervous! Everyone is afraid being around people! Everyone has feelings they'd rather stay home alone! And you know what they do? They get over it. And they stop being a piece of shit!". Again, Kyle's response to someone apparently struggling is to tell them to get over it and have a different attitude. Obviously Cartman is misusing the term anxiety to have an excuse to be on his phone, and Kyle recognizes that, but the way he goes about telling him off sounds very dismissive of people who actually have anxiety - at least on the surface. If you read into that little rant, there's more to it than that, which I'll get to later.

I think Kyle's attitude toward mental health is more complicated than it seems. He's not very good at problem identification, but once a problem makes itself known he can go one of two ways: he tries to help, or he takes a more 'just get over it' stance. The former, I think, is his natural response - he might suck at helping because he's a kid and not a professional therapist, but he usually does TRY, at least, before giving up because he can't help. The latter, in my opinion, is a direct result of Gerald Broflovski's parenting style and general attitude toward Kyle. Going all the way back to Chickenpox, we have Gerald's moronic 'gods and clods' take on society. He thinks that some people are deserving of success and others aren't, which he tells Kyle, who then unthinkingly parrots that attitude in his essay because he places so much trust in his parents' opinions. Then, cut to season 20's Oh, Jeez, when Gerald says "Kyle, you've gotta lighten the fuck up, buddy. Every day with you it's 'Dad, I feel guilty about this. Dad, I'm so confused about that.' You're a kid. You're supposed to just laugh and make fun of shit. Stop being such a pussy, okay pal? Fuck." Sound familiar? Gerald's response to Kyle's distress and anxiety is to 'just get over it'. It makes sense to me, then, to assume that this is Gerald's general attitude toward people who struggle. Keeping in mind that Gerald is successful and wants to curate the image of success, I think that's why he's SO dismissive of Kyle's problems - it's super common for parents to have the attitude of "other people have it worse than you, you have nothing to be sad/anxious about, so get over it". This is the kind of attitude Gerald seems to have, so I think when KYLE says things like that, he is parroting his father just like he did with the 'gods and clods' thing. I don't think this is Kyle's natural reaction to people who are struggling, I think that it's a trained response. Gerald thinks that people who are struggling are just pussies and shuts down/is actively annoyed by his child who is pretty consistently in distress for one reason or another. Kyle isn't allowed to feel sad or anxious at home, so he turns around and demands that other people stop feeling that way too.

Which brings me to my next point - Kyle has his own struggles with mental health. He's first of all susceptible to depression, as he says in Ass Burgers. Not everyone will get depressed after being around a depressed person, but Kyle has to distance himself from Stan because Stan's mental health is impacting his own mental health. This is a common reaction for people who are already struggling or have a predisposition to it. In addition, Kyle's response to Cartman's "anxiety" in Buddha Box is really telling. Kyle is under the impression that EVERYONE experiences anxiety, which just isn't true - he only thinks that because HE experiences anxiety and has convinced himself it's just part of everyone's life experience. Kyle basically admits in his little rant to Cartman that he is constantly nervous and afraid of being around people (which makes sense, considering what he's been through and how people generally treat him, especially in the later seasons). He says that "everyone" just gets over it and what he means by that is that he, personally, is still high functioning despite his anxiety. He's convinced himself that his experiences are universal, which they aren't.

Kyle is consistently shown throughout the series to be plagued by guilt, doubt, and phobias (such as in Turd Burglars). He also faces a lot of stress from Cartman's constant abuse, feels the weight of religious and moral expectations on his shoulders, and is under a ton of pressure from his parents to perform well in school and be a good son. On top of that, he's been through a lot of traumatic experiences (which is true for a lot of the kids in South Park, and they all deal with it differently). His peers are generally not very sympathetic to him (yes that includes Stan, lately), and neither is his father, so he's in turn not allowing himself to address his own issues. He's internalized this "other people have it worse" and "stop being a pussy" attitude and has convinced himself that it's selfish to struggle, or that everyone else is in the same boat so there's no point in talking about it.

So in short, Kyle's attitude toward mental health is likely a direct result of what he's been taught at home, and he has his own mental health struggles that he's actively not dealing with. He needs a therapist.

173 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m gonna vent here for a sec. I saw this ~4 yrs ago, I denied it. When another relationship of mines failed in May, instead of unaliving myself, I forced myself to reflect (to put it simply).

I always remembered this post and it hit me like a train when I finally got it.

Person A, who I project myself on is who I WANT TO BE: witty, highly-ambitious, confident, adventurous, and emotionally unavailable.

Person B, on the other hand, is in one-sidedly in love with Person A. It’s pure, consuming, love-sick, I’ll-do-anything-for-you type despite it NEVER being reciprocated because Person A is so unattainable, emotionally unattached, too busy chasing the world.

I had a crashing realization that I was mimicking this in EVERY relationship in my life…except, I was the obsessed Person B, always in a one-sided love with a confident, busy, emotionally unavailable person A.

Dreaming of being Person A, who I saw as the epitome of desirability (inadvertently, I found these traits attractive, too), I would write/draw/imagine Person B’s love in the way that I WANTED to be loved (inadvertently, that’s how I SHOW love, too).

I have never been the same bc of this post.

No one admits is but everyone’s REAL favorite ship dynamic is just

Person A: Character you can project onto

Person B: Your type

236K notes

·

View notes

Text

Kyle saying OMG passive aggressively for 12 seconds straight

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

My head canon for Kyle is that he has a slight overbite. I think the look of it on an otherwise angry character is adorable and dorky, too. I love fanart that have it!

4 notes

·

View notes

Video

Someone make a one hour version

Kahl Park WIP

Descend into this journey of madness as Movie Maker messes up the overall quality of this godforsaken piece of garbage.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

They actually swear like the SP kids I love it

uno

506 notes

·

View notes

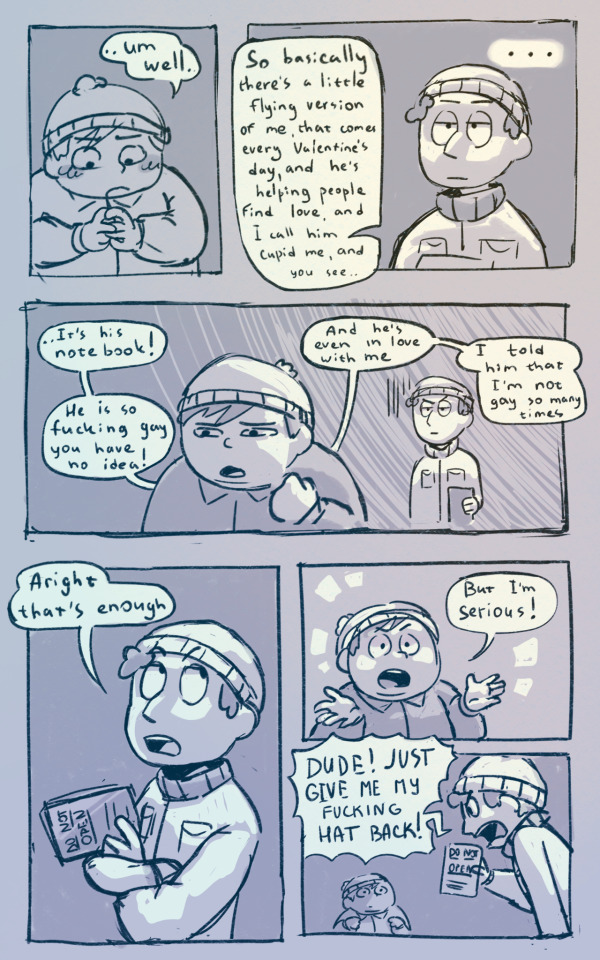

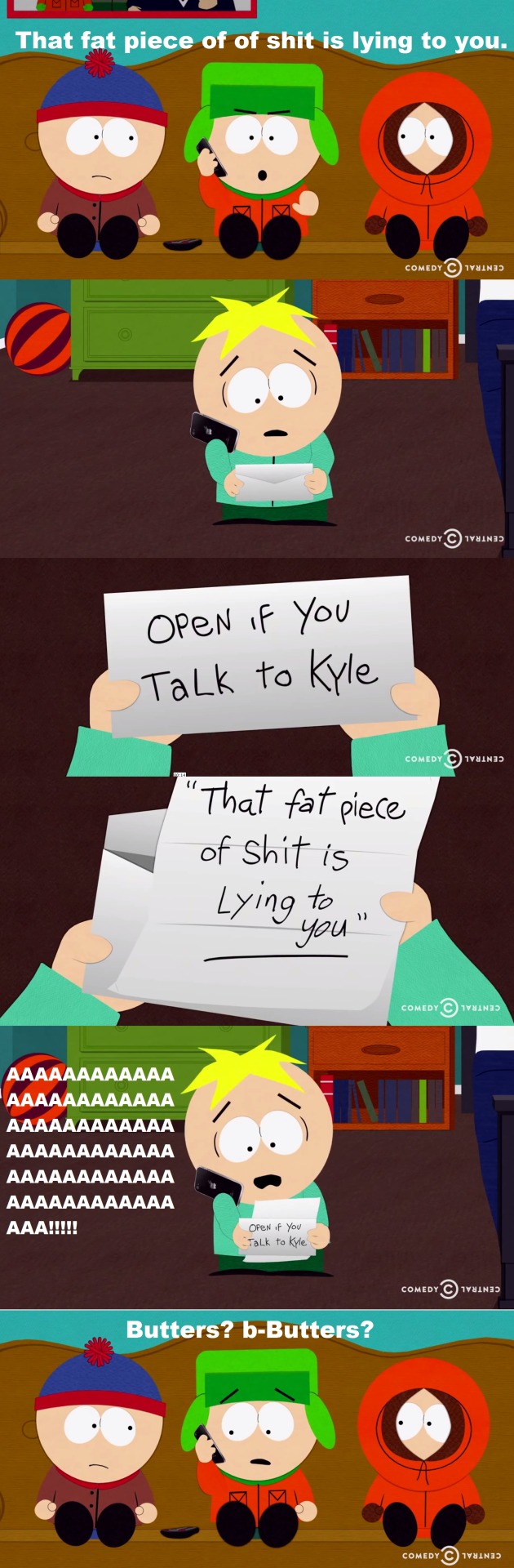

Photo

This fucking kills me

3K notes

·

View notes