Text

Safety at Sea the Lifeboat

Seafaring has never been safe, and yet until the late 18th century no one had really thought about how to save people. The British Humane Society for the Recovery of Persons Apparently Drowned was founded in 1774, but it was concerned with the resuscitation and care of persons found on the beach, as was the Humane Society of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

The Lifeboat in the Act of Saving Part of the Crew of a Ship Wrecked Near Tynemouth Castle after W Elmes, 1803 (x)

The Dutch were a little further ahead, having developed a so-called rescue vessel in 1769, but it is not known whether it was ever used. As is always the case with many things, something has to happen before there is a reaction, and that was the case in 1789. The ship (supposedly a coal ship) Abenteur was caught in a violent storm in the mouth of the River Tyne, and all attempts to rescue the crew failed due to the weather. This led three men, Henry Greathead, William Wouldhave and Lionel Lukin (who filed a patent in 1785) to develop a lifeboat.

William Wouldhave thinking about his lifeboat, by Ralph Headley 1896 (x)

All three were given a reward but it was Greathead who was allowed to build his design, including design ideas of the others. His boat was open, with a high bow and stern. And it was given extra buoyancy by cork belts on the hull. The first example was called original and had room for 24 men. Subsequently, over 30 were built by 1840 and placed on the coasts of England.

With the breeches buoy, developed from 1807 onwards, more than 140,000 lives were saved by 1824. (x)

Extract from the Caledonian Mercury of Edinburgh, Monday 28 December 1801

© The British Library Board

1824 was a special year because Sir William Hillary founded the National Institution for the Preservation of Life from Shipwreck, later renamed the Royal National Lifeboat Institution. They financed their stations, which were headed by a Coxwain, and their crews through donations.

The Zetland, an Original-type lifeboat built by Greathead stationed at Redcar 1801–80 (x)

In 1845, the first lifeboat with a light iron hull was developed. The American Joseph Francis, who had already developed several examples, then tried it with a punched corrugated iron hull. These boats were much lighter and could be brought into the water more quickly than the previous heavy wooden boats. This led to rapid success, and when steam engines were introduced in the late 19th century, salvage was even faster.

Every country today actually has lifeboats that go out to save lives in an emergency, even if it might put the crew’s own lives in danger.

131 notes

·

View notes

Text

Treatment of an almost drowned

I am reading a book about Surgeons at sea and just stumbled upon what happens to men when they go overboard. Even though most of the men on board could not swim, about 1/3 of the men who went overboard survived.

Could this man be saved by throwing empty barrels or other things overboard that were floating or by launching a boat.

So the rescued man was put over head, over a barrel to roll the water out of his lungs. Then most of the surgeons swore of using hot onion soup, this should stimulate and strengthen the breathing. Other treatments were bleeding or blowing tobacco smoke into the lungs. If the patient survived this treatment, he was allowed to rest for a few days before he had to go back to work.

Unfortunately the section is only very short, it would be interesting to know what else was tried

269 notes

·

View notes

Text

Acting Lieutenant

An acting lieutenant is a midshipman who has been temporarily promoted to the rank of a lieutenant. This authorised him to take on the duties that the new rank entailed. He was then also addressed with his new rank, the acting was only used in official papers. However, this is not an indication that the rank will be officially confirmed and that the midshipman will be promoted to this rank as soon as he has passed his exams, but it can be supportive if he can show that he has already served in this rank.

Midshipman now acting lieutenant Calamy gets the white patches on his uniform removed. - Master and Commander

This type of temporary promotion has existed since the 18th century and was applied to many ranks, including acting midshipman and acting master. However, the salary was not always adjusted for this time, but it did entitle him to wear the appropriate uniform if it was available.

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wreck of the William Young, Lake Huron, photo by Becky Schott

The William Young was built as a schooner in 1863 and cut down into a barge later. She was carrying coal and being towed with 3 other ships when she began to take on water. She sank but the crew was rescued in the Straits of Mackinac that day in October 1891. The 139 foot long ship sits upright in 120 feet of water on the Lake Huron side of the bridge. She is one of only two schooners in the Straits to still have a wooden wheel on the stern. There are many dead eyes still on the ship and coal inside. The bow is crushed but a windless and wood stock anchor can still be seen.

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Do you know what today is? Rope Yarn Sunday.

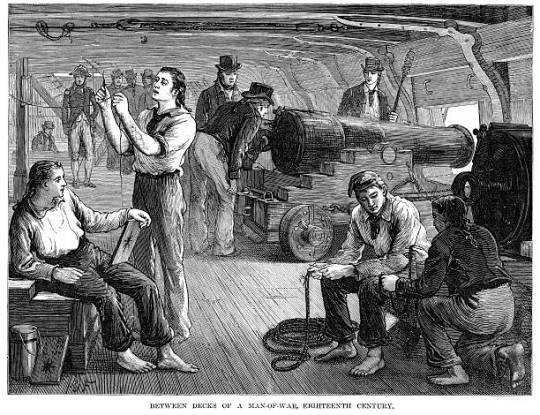

Between Decks of a Man-of-War, (x)

Back in the age of sail, that meant half a day’s work on board and then some free time to mend the clothes but also to relax. Therefore have a nice sunday.

830 notes

·

View notes

Text

Special sails

We are more familiar with ships that go up to the topgallant sail (t'gallant or t'garns'l), but there are still some special sails that are above it, these are the Royal, the Skysail and above that the Moonraker. Because of the height they reached, these ships were also called skyscrapers, but please do not confuse them with the skyscraper sail, which was hoisted above them in a triangular shape on much larger ships like clipper or steal barques during the 19th and early 20th century.

Royal

A royal is a small sail flown immediately above the topgallant on square rigged sailing ships. It was originally called the "topgallant royal" and was used in light and favourable winds. Royal sails were normally found only on larger ships with masts tall enough to accommodate the extra canvas. Royals were introduced around the turn of the 18th century but were not usually flown on the mizzenmast until the end of that century. It gave its name to a Dutch term for a light breeze-the Royal Sail Breeze or bovenbramzeilskoelte was a Force 2 wind on the Beaufort Scale.

Skysail

In the course of the 18th century (although the first written records do not exist until 1807), skysails began to be hoisted over the Royal, again in good weather and light winds.

Moonraker

The word itself dates back to the 18th century and was the name for a sail that was hoisted directly above the sky sail, and it was only hoisted when there was very little wind, because if the wind was too strong, it would simply tear off.

The Regina Maris, a danish barquentine from 1908 with a watersail ( red circle)

Watersail

A watersail is a sail hung below the boom. It is used mostly on gaff rig boats for extra downwind performance when racing. Often a watersail will be improvised from an unused foresail. Its psychological effects may be more effective than its aerodynamic ones. Surprisingly, its use can be traced back to as early as 1373. Possibly even earlier, since the 12th century.

188 notes

·

View notes

Text

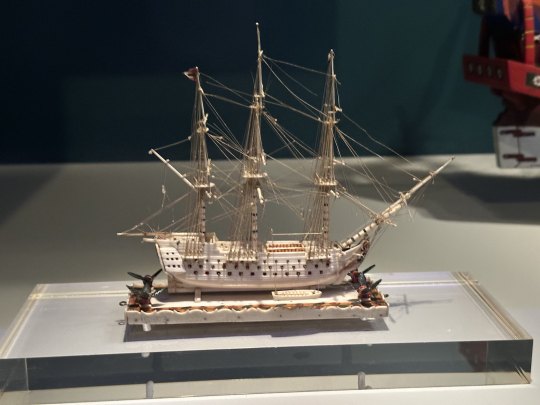

Went to the local museum and found the One Napoleonic Thing there

tiny bone ship!

(The whole exhibition is pretty neat, it's about scale models and museum models, all the descriptions are a little silly/sarcastic)

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Orlop

Large merchant ships with a fixed deck are documented as early as the 13th century. This deck was called an averlop or overloop. In the course of the 17th and 18th centuries, the height of the deck in relation to the waterline changed. Until then, it was not only the lowest deck in general, but also the lowest gun deck. Below this began the so-called space, which could be divided by planking or could also have a light and therefore watertight deck. The overlop could be covered by a canopy. It is not clear from the sources whether this deck was given its own name. The term ‘Verdeck’ also generally refers to a deck and Dutch sources usually only contain descriptive lists of decks. In German usage in the 17th century, there is also no evidence of a distinction between decks by name. In Hamburg in 1685, all decks were described as overlop (‘overflow’). In Röding's dictionary of 1798, overlop is translated as overflow and generally as deck. In contrast, the English orlop is translated in the same work as Kuhbrücke ( cow bridge - where the cattle were housed) under the lowest deck.

Orlop deck of a ship of the line (in red), 1728, in: A Ship of War, Cyclopaedia, 1728, Vol 2

The orlop deck was used as an ideal storage area and at the same time as a recreation room for some of the ship's crew. As the deck did not have to be cleared or remodelled during combat operations, cabins and rooms located here were permanent and could even be locked. The purser could therefore store his valuable or dangerous items (small arms) here, and the surgeon his medical items (medicines, instruments), so that they were protected from unauthorised access. As the deck was below the waterline, it was one of the safest places on board during a battle. For this reason, the ship's surgeon often had his workshop down there, as he could do his work unhindered by the fighting and the wounded were brought to him on the orlop deck.

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lost the handle to his name

Said about minor officers aboard merchant ships who were relieved of their duties by the captain and were sent "from the land of knives, forks and teacups…" (i.e. the officers' mess) to the forecastle, perhaps because of their behaviour. The phrase refers to the loss of Mr. in front of their names.

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ahoy, shipmates!

Over the course of several delayed flights this weekend, I devoured a paperback copy of Edgar Allan Poe's The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket. I found it enjoyable, if not a Great Classic Work Of Literature.

My question to you now is, there's a chapter in the middle of the book where our castaway hero encounters a plague ship. It moves erratically through the water before them, with what appears to be a smiling, nodding sailor at the rail, acknowledging Arthur and his fellow castaways.

However, as the ship approaches, the stench of death washes over our hero and his companions, and as it passes under their stern, they can see that all aboard the ship are dead of some terrible, unknown disease, and that the smile and nod they perceived were the rictus of death and the movement of a seagull feasting on the dead sailor's flesh.

This is my first time reading this book, and yet there's something viscerally, intensely familiar about this imagery. I feel like I've read this somewhere else before. Perhaps it was in a graphic novel, because my mental image of this scene appears in a sort of comic-book style.

Does anyone have any ideas where I might have encountered this before? Any help would be appreciated.

@clove-pinks

@benjhawkins

@ltwilliammowett

@saranilssonbooks

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Suddenly struck with a need to explain to you how boat pronouns work (I work in the marine industry).

When you're talking about the design of the boat, you say "it".

When the boat is still being built, your say "it".

When the boat is nearing completion, you can say "it" or "she".

When the boat is floating in the water you probably say "she", unless there is still a lot of work to be done (e.g. no engine yet) then you say "it".

When the boat is officially launched and operating, you say "she". If you continue to say "it" at this point you are not incorrect but suspiciously untraditional. You are not playing the game.

If you are referring to a boat you don't really know anything about you may say "it" ("there's a big boat, it's coming this way"). But if you know its name, it's probably "she" ("there's the Waverley, she's on her way to Greenock").

If you are talking about boats in general, you say "it" ("when a boat is hit by a wave it heels over")

If you speak about a boat in complimentary terms, it's "she" ("she's a grand boat"). If you are being disparaging it may be it, but not necessarily ("it's as ugly as sin", "she's a grotty old tub").

If she has a boy's name, she's still she. "Boy James", "King Edward", "Sir David Attenborough"? The pronoun is she.

If it's a dumb barge (no engine), you say it. But if it's a rowing boat (no engine), you say she.

I hope this has cleared things up so that you may not be in danger of misgendering floating objects.

85K notes

·

View notes

Text

If you're in the need for some kind of magical artifact of magic for your setting, consider Fresnel Lenses which are used in lighthouses:

These things are Alive.

13K notes

·

View notes

Text

Classic sea shanties like:

"I fucking hate this ship and I cannot wait to get off."

"I got off the ship on the dock but I know I'm going to get back on the ship when my leave is up. Fuck."

"Storm."

"Big storm."

"Is it just me or does this ship have like. Really clean lines. Like damn. Okay. Not saying I'm feeling attracted to the ship, per se, but. Damn."

"Sometimes you see weird shit that you cannot explain and you just kinda have to shrug and go. Welp."

54K notes

·

View notes

Text

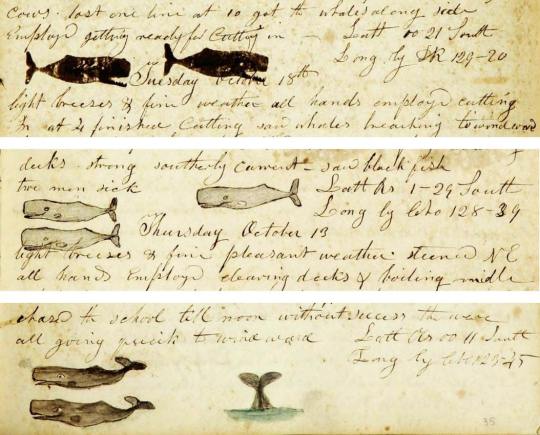

Merry whales in the log of the ship Susan, kept by Reuben Russell. Nantucket Historical AssociationPublic Domain

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Sailors and Mental Health

Please note: This post is about mental health, attempts at treatment and accommodation, self-harm and suicide. If you are affected by what you have read or have current problems that you cannot deal with on your own, please contact a mental health helpline.

Do not suffer in silence.

Another type of disease affected the men as much as any other type of disease. But it was either not recognised at all or only with difficulty. We are talking about mental illnesses.

References to mental illness and their treatment can be found as early as 5000 BC with skulls showing evidence of trepanation. Texts from Ancient Egypt, China, Ancient Greece and the Romans also indicate an awareness of different types of mental illness dating from 1500 BC to 200 AD. After the fall of the Roman Empire theories of mental illness, including different personality types and temperaments (Theophrastus) and ‘rational explanations’ (Hippocrates), largelyreverted back to the belief in demons and other supernatural causes. It took nearly 1000 years before the first hospital for the mentally ill in Europe, Bethlem Royal Hospital, admitted its first patients in the 1300s. Key theories and ideologies emerged over the next 300 years largely driven by the Renaissance period that swept through Europe. Descartes’ ‘theory of mind’ and Burton’s ‘Anatomy of Melancholy’ are examples of influential works from this period.

This post, however, is mainly about an insight into the treatment and care of sick Sailors of the 18th and 19th century of the Royal Navy.

By the end of the 18th century the Surgeons had noticed an increase in the number of Sailors being admitted to one of London’s Asylums due to mental breakdown, especially after major battles. Sir Gilbert Blane (1749-1843), Physician of the Fleet, quickly realised that during the war the number of such men had increased sevenfold and the wings for such cases in the Royal Navy Hospitals were expanded during the 19th century. He recognised that the men often suffered from severe anxiety, depression and trauma. However, he did not see it as such as it is today. He only recognised the symptoms, such as partial paralysis, sleep disturbances, dysesthesia, delusions and more. As was the case with soldiers in the army, these illnesses were attributed to the war.

Most of Bethlehem Hospital by William Henry Toms for William Maitland - William Maitland’s History of London, published 1739 (x)

This was also partly the case, but the other circumstances such as malnutrition, trauma through violence and mistreatment among each other were not seen. French physician François Boissier de Sauvages de Lacroix, however, described something he had noticed in the Sailors in their normal everyday lives. He called it brain fever. The patients were restless, had severe insomnia and delusions, and their moods could go from happy to sorrowful in a short time. Despite the lack of sleep, the men were overactive and yet powerless at the same time. What he found there were the first documented cases of biopolar disturbances. Although he tried to treat them like a fever, he often had to watch the patients injure themselves or even jump into the sea.

The symptomatic treatment of such diseases was a fundamental problem. No one really knew how to deal with these men, so schizophrenia was treated like malaria or depression was dismissed as melancholic mood, which was treated with sea air, sun bathing and walks. People hoped for help in the asylums of the cities. The Admiralty sent its men to Hoxton House. Between 1794 and 1818, 1289 men were treated there, of whom 364 were discharged as recovered. 272 died as a result of the treatment and 52 simply disappeared. The more serious cases, 494, were transferred to Bethlem. There they were considered incurable. The Bethlem in London was an asylum with a terrible reputation. It had been run under inhumane conditions since the 14th century.

The hospital may have looked like a palace, but treatment of patients was hardly ideal, as shown in this etching of William Norris in 1814 (x)

106 Sailors and 20 Prisoners of War had to share two rooms 7.9m long and 4.9m wide. Basic equipment such as tables, chairs, some beds, plates and cutlery were forbidden. Sanitary facilities were almost non-existent and men were left like cattle in their own filth. The diet, which typically consisted of: 450g (16oz) red meat, 450g (16oz) vegetables, 55g (2oz) cheese, 570ml (1 pint) broth, 1 litre (2 pints) tea, and 2 litres (4 pints) 'small beer’ per day. There were no medicines, fresh clothes or even fresh air. Ultimately, the men were left to fend for themselves. Officers were therefore often placed in private institutions such as Bath, where they were given a cure to restore their health.

However, unlike really physically recognisable illnesses, mental illnesses had a stickma attached to them and many hid their problems in order to avoid social problems. Or they were not taken seriously and so depression was perceived as a mood or a woman’s problem. Sailors, who were considered to be masculine and tough, did not have such illnesses (people with mental illnesses were also called lunatics) according to society. However, the opposite was the case. The Navy had a major problem with depression, which was exacerbated by pressure and expectations in the officer ranks. Especially in the Expedition service in the early to mid-19th century, this pressure was exacerbated by the demand for results in a short time, the poor prospects for quick promotions and the desperate position some found themselves in. What pushed some to suicide, that’ s what happened to the two captains of HMS Beagle. On their first expedition, Captain Pringle Stokes shot himself and the later Vice Admiral Robert FitzRoy took his own life with a razor.

Patients in Bethlem, also called Bedlam, in the fresh air, by K.H. Merz 1834 (x)

The cases became more frequent and many an officer was taken out of service with serious self-inflicted injuries and placed in one of the naval asylums. At the beginning of the 1820s, as the conditions of the wounded in the hospitals changed, so did those of the mentally ill. The diets were changed and the accommodation became more comfortable. And labour therapy was tried, although not entirely successful, because the men who seemed physically healthy could then work in the gardens for fresh vegetables, which saved money and labour. (Only after WWI did these treatments intensify and show some success). In addition, medicines were now being tested for the benefit of mental health and experimental operations were also being carried out. But also questionable water and cage therapies were tried.

For example, William Kemp was given mercury treatment in 1830. He had been taken to the Haslar Hospital for conspicuous behaviour, violence towards crew members. William Kemp inflicted, who was brought to Haslar in 1830 for his violent and noisy behaviour and, when a mercury cure failed to cure him, was treated as follows: 'Since the commencement of his present illness his bowels have been kept open by the compound rhubarb pill, the compound aloetic pill, and small doses of sulphate of magnesia and antimontartrate. A blister was placed on his head without benefit, but the cold infusion had the effect of quieting him and making him less noisy.’

William Kiddall, a sailor who was admitted to Haslar with mania in 1826, fared differently. Six years later, on 17 August 1832 at 11.30am, he was 'observed yawning’. As he was “unable to account for his sensations”, he was put to bed, and at 2 p.m. “vomiting and purging” began on the order of the orderlies. The report continues: He was then placed in a warm bath and given brandy, aromatic ammonia [i.e. smelling salts] and opium tincture to awaken the vital forces, which were obviously very low; but there was no reaction. At 4 p.m. he was again placed in a bath and a venisection [bloodletting] was performed on both arms and on the internal carotid artery, but hardly any blood came out, and what little was found was viscous and extremely dark in colour. Then a branch of the temporal artery was opened and about a drop of blood with the same appearance was obtained. At 9.30 p.m. he was dead.

As you can see from these two examples, it was more a pure symptom treatment but not a real help. None of the men really recovered and they often died, either as a result of the treatment itself, see above, or they took their own lives. Dealing with these diseases only happened in the 20th century and during the great world wars, but for everyone before that it was often a pure torture.

256 notes

·

View notes

Text

Exposed by a Shark

In 1799, a naval scandal sent shockwaves through the British West Indies: and american Brig, the Nancy, was suspected of smuggling enemy goods. These were the days when four sparring countries filled Caribbean waters with friction and suspiction. Britain, Spain, France and the Netherlands were engaged in a bitter colonization campaign, each vying to be masters of the sea. Though America was neutral, it came as a bitter blow for Britain when they found evidence suggesting that their (ex) brothers across the Atlantic were trading with the Dutch.

The Flag of the United States, First hoisted at the Island of St. Thomas by Capt. Hugh Montgomery, on the news of the Declaration of Independence, 1776. A brig called Nancy, not the “Nancy”, is is depicted here. (x)

Fingers immediatley pointed towards the brig Nancy, which had set sail from Baltimore to the Dutch island Curacao on 3 July that year. From there she saild to Haiti, where HMS Sparrow, was sent to intercept her. After fleeting chase, she was captured and escorted to Port Royal, Jamaica, where a thorough search of the vessel commenced and all of her cargo seized. Nancy’s captain Thomas Briggs, was questioned at length, but, to all surprise nothing incriminating was found. To all intents and purposes, everything was legitimate, and it appeared as though British suspicions were unfounded. A furious captain Briggs even produced official documents that cleared the ships of any wrongdoing. Just when it seemed that the americans were about be acquitted, Fate dealt Britain a surprising hand.

A lieutenant named Michael Fitton, of the Royal Navy, serving on HMS Ferret, but he was on a Tender from HMS Abergavenny at the time, when he caught a shark. Inside the creature’s stomach was a bundle of papers, which, it transpired, were the Nancy’s real documents, proving beyond any shadow of a doubt that the vessel was indeed carrying contrabands of war.

The original shark papers (x)

Captain Briggs had thrown these papers overboard when he realized the Sparrow was on his stern, and a passing shark had devoured them. The paper’s he’d handed over the Sparrow were fakes. A further search of the Nancy was conducted, and secret hideaways containing the concealed commodities were discovered. The Nancy was officially declared as a prize and Captain Briggs and his crew were taken into captivity.

Otago Daily Times, Issue 17960, 12 June 1920, Page 10 (x)

The shark’s jaw were inscribed with the words ‘Lieut. Fitton recommends these jaws for a collar for neutrals to swear through.’

216 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was reading Utmost Gallantry by Kevin D. McCranie and came across an intriguing line. When Captain Isaac Hull of USS Constitution was fleeing a British squadron in 1812, he passed within gunshot range of a British frigate, but the enemy held her fire. Hull later wrote that the frigate "did not fire on us, perhaps for fear of becalming her as the wind was light."

I immediately remembered that Frederick Marryat wrote something very similar about a ship's guns somehow stopping the wind, and found it in The King's Own: "wind lulled by the percussion of the air from the report of the guns."

This was apparently a genuine sailors' superstition!

Action at Sea: an English and a French Frigate Engaging by Robert Dodd c. 1802 (ArtUK).

I searched Google Books for more references and found one in a late 18th century dispatch to the Admiralty quoted in Memoir of Robert, Earl Nugent: "their guns had so lulled the wind as to leave us little prospect of getting nearer to them."

I can see how, in an era long before smokeless powder, it might seem like firing large guns made the wind die down as the combatants were enveloped in clouds of smoke.

@ltwilliammowett have you heard this one?

29 notes

·

View notes