Text

"I tell you, 21 years and I still have the anger. But I have sense enough to chanel that nager into working with my program and working with others. If I didn’t have that anger, I might not do anything. But when I read a letter, and it’s clearly another joyce ann brown story that you can see that this person did not comit that crime—that makes me angry, and it makes me angry enough to get up, make some telephone calls, find an innocence project, try to find some kind of system for that person that’s still sitting in prison, going through all the things that you went through during the nine years, five months, and 24 days…So, all of that anger. But we talk about it, and we do it because we need to go back and assist those that are still left behind.” --Joyce Ann Brown (https://youtu.be/w6GOBA-kdCM)

In an article scholar Shirley Wilson Logan introduces the idea of "Righteous discontent." Logan explains righteous discontent as “the rhetorical situations [in which] women…speak with moral authority borne out of the strong belief that they [are] correcting injustices, not just advancing ideas” (21). Evaluating past feminist rhetoricians, Logan suggests that there are three “manifestations” of righteous discontent: “(1) Telling the Stories of People, (2) Invoking the Past, and (3) Establishing Common Identification” (21).

Joyce Ann Brown lived a life of righteous discontent. Wrongfully sentenced to life in prison for a crime she did not commit, it took Joyce nine years to clear her name. But once she got out, she didn't stop there. She published her story. She started an organization to help others who were also wrongly imprisoned. She used her experience and pain to help others. She allowed her anger--her just and righteous anger--to push her towards good.

Logan says that "righteous discontent" is meant to “call upon other to speak out for a more just universe” (32). Joyce Ann Brown--with her life, her pain, her story--lived a life that did exactly that.

Source: Logan, Shirley Wilson. “Bending Toward Justice: Women’s Rhetorical Perfomances—Local and Transnational, Then and Now.” Retellings: Opportunities for Feminist Research in Rhetoric and Composition, edited by Jessica Enoch and Jordynn Jack, Parlor Press, 2019, pp. 19-33.

0 notes

Text

"[Aristotle] famously wrote that the female offspring is the first step towards ‘monstrosity’...Women, then, inhabit monstrously different bodies, and this difference rules every aspect of their being, even their soul. In this way, any departure from the bodily norm is seen as potentially 'crippling' in all other capacities, even the soul...Femininity and disability, then, are classically intertwined."

--Jay Dolmage, "Metis, Mêtis, Mestiza, Medusa: Rhetorical Bodies across Rhetorical Traditions"

0 notes

Text

Yall know I think about this case OFTEN. Darlie Routier. The way they crucified her for grieving in a way that was deemed "unacceptable." I think about this case at LEAST twice a week. Often more.

Composition and Rhetoric scholar Lindal Buchanan wrote a book titled Rhetorics of Motherhood. In the book, she addresses the identity of a mother and the rhetoric society employs when describing it that works both for and against a woman. She explores “How is the construct [of motherhood] defined? How are maternal appeals crafted, presented, and performed? What do they communicate about gender and power? How do they affect women?” “Rhetorics of motherhood,” Buchanan writes, “not only benefit women, giving them authority and credibility, but also impede them, always/already positioning them disadvantageously within the gendered status-quo” (5). While the entire book Is so good, in one chapter specifically, Buchanan borrows from scholar Richard Weaver, Buchanan discusses what Weaver calls “Devil terms” and “God terms”: God terms being words that invoke positive feelings and the ideal good, Devil terms being their evil counterparts (8). She then argues that “mother” is a cultural God-term, invoking feelings of good and bringing to mind words like “children,” “home,” “love,” “empathy,” “self-sacrificing,” and “strength.” The Devil term that counters mother, according to Buchanan? “Woman.” Rhetorically, this word is grouped in with others like “childlessness,” “work,” “self-centeredness,” “materialism,” “immorality,” and “sex” (9).

It strikes me that these terms were used so much in Darlie's case. They called her selfish. They called her materialistic. They called her immoral. They pointed out her boob job, that she went to a strip club, how much money she spent, the type of clothing she had. They used this all against her.

Rhetoric is powerful. And in some cases, dangerous.

Source: Buchanan, Lindal. Rhetorics of Motherhood. Southern Illinois U P, 2013.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"As women, we have been taught either to ignore our differences, or to view them as causes for separation and suspicion rather than as forces for change. Without community there is no liberation, only the most vulnerable and temporary armistice between an individual and her oppression. But community must not mean a shedding of our differences, nor the pathetic pretense that these differences do not exist. Those of us who stand outside the circle of this society's definition of acceptable women; those of us who have been forged in the crucibles of difference -- those of us who are poor, who are lesbians, who are Black, who are older -- know that survival is not an academic skill. It is learning how to take our differences and make them strengths. For the master's tools will never dismantle the master's house. They may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change. And this fact is only threatening to those women who still define the master's house as their only source of support."

--Audre Lorde

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

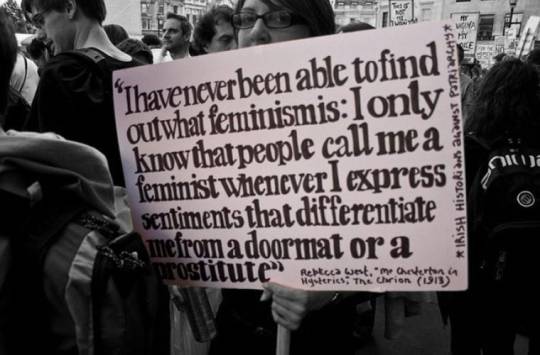

I remember the first time I ever expressed the ideas of feminism. The response was "You can think that way, but why don't you just not reference feminism? You think a man would want to marry you if you express these loud and radical ideas?" It was definitely bizarre and confusing. I felt disoriented and lost. Wasn't that the very thing I was talking about? NOT letting what men think of me define me? Going AGAINST this idea that men should run my life? Trying to make my voice heard and accepted as it is? I didn't understand it. And, the weirdest feeling of the entire situation was I knew the person saying this to me was coming from a place of care and concern. A genuine place of love. I knew they believed what they were saying, that they thought I would forever be alone if I stood up for myself and expressed my own value, strength, and place in the world. I didn't understand it. And I don't think I ever will.

Source: The photo came from this article, which was a really great read. https://theswaddle.com/arguments-against-feminism-research-data/

1 note

·

View note

Text

"The feminism I had studied was too white, too American. The only issues defined by white women as 'feminist' had structured discussions. Their language revolved around First World 'rights' talk, that Enlightenment individualism that takes for granted 'individual' primacy. Last, but in many ways most troubling, feminist style was aggressively American."

--Haunai Kay-Trask, "Feminism and Indigenous Hawaiian Nationalism"

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hysterical

/həˈsterək(ə)l/ (adjective): feeling or showing extreme or unrestrained emotion

When your body is used without your permission, who wouldn't have extreme or unrestrained emotions?

0 notes

Text

"We are assembled to protest against a form of government, existing without the consent of the governed – to declare our right to be free as man is free..."

-Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Seneca Falls Convention

0 notes

Text

Dr. Jacoby: “Bobby, were you sad when Laura died?

Bobby: "Laura wanted to die.”

Dr. Jacoby: “Did you sometimes get the feeling that Laura was harboring some awful, terrible secret?…A secret bad enough that she wanted to die because of it? Bad enough that it drove her to consciously find peoples weaknesses and prey on them, tempt them, break them down? Make them do terrible, degrading things? Laura wanted to corrupt people because that’s how she felt about herself.”

Laura Palmer. The great martyr of Twin Peaks. The supposedly innocent victim, whom we later find out was a cold hearted, manipulating, coke-dealing sex worker. Then another layer of Laura’s life is revealed, and we learn she is a victim of incest–her own father, controlled by a demon named BOB, came to her room regularly to rape her. And then she is murdered by him. And throughout the series, the great question is: Did Laura WANT to die? Was she living a dangerous, scandalous life in hopes that she would be killed? Was she asking–begging, even–to be murdered so she could be released from her pain? And we are meant to conclude yes: Laura, a woman who was raped and murdered by her own father, is somehow now at peace after being brutally killed.But let’s be honest: is she? Did she want to die? Was she “asking for it”–whether that “it” be rape or murder? Who would ask for that? Maybe she wanted to die, but did she want to die like that? Violently? Brutally? Horrifically? And then tied up in a plastic sheet and left on the shore? No one would want that. Nobody.

0 notes