Text

A year ago today I finally finished writing my dissertation, edits and all. Looking back all I can feel is pure joy for staying the course and getting my Ph. D!!!!!!!!!

WHEN YOU REALIZE THAT YOU NEVER HAVE TO WORK ON YOUR DISS AGAIN:

138 notes

·

View notes

Text

Should Educators Expect Real Voices from their Students?

Student’s rights, teachers expectations, and vocalizations.

I have written this entire dissertation under idea that there is really no such thing as student voice. The Student is a role an individual plays. It is not a permanent role or even a semi-permanent role a person plays, like playing the role of a mother, brother, husband, friend, employee or daughter are. It is a role that is bound by time and, in our current social context, enforced by institutions that a large number of individuals do not trust. When individuals come in contact with a role, that role can be played cagily, or with sincerity, depending on what the individual determines will be the most appropriate for the situation. Much like a performer in a Greek drama, the individual wears the role like a mask. The mask itself does not have a voice. The individual speaks through the mask. And although the performance calls for preset lines (which is a restriction in autonomy), the voice that comes through the mask is still the voice of the individual. It was my goal in this dissertation was to examine how individuals coped with saying their lines through the mask, not focusing on the mask itself.

When thinking about how individuals use their voices in the academic context I believe it’s time we as educators ask ourselves if we have the right to expect or even desire students project their authentic voices in their work. There are psycho-social and emotional ramifications to the voice. The voice isn’t closest to the brain. It is nestled in a cradle north of the heart making it the heart’s highest communicator. When we ask diverse students for their true voice, we are asking them to speak from the heart.

While that request sounds wonderful in a touchy-feely way, it is ultimately a dangerous request. When educators ask diverse students to use their authentic voice we are asking a vulnerable population of students to be even more vulnerable in an institution that does not value, and sometimes punishes, vulnerability. Moreover, we live in a society where duplicity is often rewarded and vocalizing one's truth can have serious long term repercussions on one’s career and social standing.

As a result of these truths, I don’t believe educators have the right to expect students of any background to project their diamond voices in their writing. It’s not really our place to ask students to put themselves on the line, especially if they secretly harbor ideas that could be seen as radical or repugnant. Desiring to hear the voices of individuals in the student role can also backfire on a teacher, causing a contentious atmosphere between students and educators when students vocalize ideas that the teachers perceived to be offensive. A prime example of this is backlash the Sacramento Area Youth speaks program got from Caucasian teachers when educators felt students’ poems were anti-white (Watson, 2012). Thus delving into the realm of the voice can be a minefield for everyone who is involved.

While I wrote this draft, more than once other researchers asked me, “If students are using so many voices, how can they know which one really represents them?” When analyzing that question, I feel the same could be asked of seasoned scholars, teachers and administrators. In our own careers as educators and scholars we frequently use languages and voices that are not our own to navigate our journeys through academia. How do we know which voice really represents the core of who we are? With that question in mind, when we know we play different roles to make it in this society, why do we ask for, hope for, and sometimes, expect and grade students on using their real voices in their work when we don’t do that same thing all of the time in our own work? How can we demand students to be brave in a space that sometimes intimidates us into silence? Are we talking to ourselves when we ask students for their real voices? Are we giving out the advice we give ourselves but somehow can’t act on? Before we can ask the adults who come to us as students to project their real voices, we need to the more difficult work of modeling that behavior by practicing what we preach in our work.

These questions make it clear before we can ask individuals in the student role to project their real voices, we need to examine our own motives for that request to ensure the projection of voice is for students’ benefit in and outside of the classroom. Self-reflection can lead to some hard truths about what our real voices would say if vocalized out loud. Maybe the truth is we are working on a campus initiative that needs more brown people to give the appearance of a more diverse campus. We might find that we have been intellectually “slumming it” by asking students from backgrounds that are different from ours to share their real voices so we can peer into their lives and exoticize them. And maybe we are just feeding our teacher-savior complexes. We have to do that difficult, complicated inner work and know who we are inside so when students are going through their inner work process in preparation to project their voices, we can relate to them as human beings who struggle with the same issues under the same institutional pressures.

All cynicism aside, I think the majority of educators who aspire to hear their students’ voices do have loftier aspirations. Those educators, like myself, see the projection of authentic voice in the classroom as practice for projecting truth in our larger tumultuous society. Speaking up and speaking out against our systematically oppressive monoculture is extraordinarily important, especially now with the resurgence of bigotry and violence as a result of the recent presidential election. Xenophobic and homophobic groups will use all types of rhetoric at their disposal, like denying racism exists, online trolling, hate speech and fake news, to denigrate diverse people and to excuse violent behavior against diverse individuals. Diverse students will need more experience than ever to face down these volatile factions of the American populace. When educators work with diverse students to voluntarily cultivate their voices as a means to empower individuals talk back to oppression and the status quo, that is when the real work of voice can begin to take place.

0 notes

Text

Strategies for Supporting Diverse Writers in Diverse Contexts

Conclusion part 2

Strategy 1 : Build Trust Through Positionality and Allyship

Before any teaching can begin, it is crucial to lay the foundation for instruction by positioning oneself as an ally to diverse students. It is important to position oneself as an ally to diverse students in order for those students to sense they can trust the educator with their more radical ideas. Allyship does not mean an individual agrees with everything the student says or that the individual is a radical social activist. It is more of an indication of a willingness to listen to diverse people while refraining from judgment. Allyship also indicates an individual is willing offer support and advice to help further the student’s goals.

Indicating allyship can be a difficult process, especially for Caucasian allies. On the surface, indicating one is an ally might seem as simple as posting ally signs for different groups, like undocumented immigrants or LGBTQ students, or wearing a safety pin to indicate diverse students are safe in the presence of the individual wearing the pin. The problem is in the current global climate of rising xenophobia, it is hard for diverse students to believe these indications of allyship are nothing more than public displays of the shallowest form of acceptance. Most students begin to recognize faculty members as allies only after a consistent record of supporting diverse students through concrete actions. That action does not need to be drastic. To become an ally, start with actions that are in your comfort zone. Those actions could be as simple as establishing contact with diverse student groups you’d like to work with, talking to diverse students about issues that are impacting them to get their perspective, regularly attending talks that feature issues that are important to diverse students, offering to mentor diverse students, speaking against school policies that could hurt diverse students or pushing to make the faculty in one’s department more diverse. In the classroom, allyship could take shape by inviting diverse speakers to give talks or presenting texts with a range of perspectives from diverse authors.

No matter what actions an instructor decides to take, in my opinion, the most successful actions have compassion, humility and mutual human respect at the core of them. The most successful allies I have observed never tout their role as an ally, especially since using the term “ally” as a badge of honor can come across as using diverse student issues to boost one’s career. Usually students come to know professors are allies through word of mouth from other students who trust the professor. Thus, making respectful connections with students during actions of allyship is critical.

Strategy 2: Create Safe Spaces for Discussion

There are a number of ways educators can designate their classroom or office as a safe discussion space. For example, at the beginning of a class, an instructor can designate their class as a safe space by indicating that designation in the syllabus. Within the syllabus, the instructor can outline their ground rules for the safe space and ask students to provide input on those ground rules so each safe space classroom is unique to the students who are present. Here are three sample ground rules I present to students when establishing a safe space:

When discussing a topic, each person may speak for a maximum of 1 minute.

If an individual has already spoken on one topic, they must remain quiet until every student who wants to speak on the topic has the opportunity to say their piece.

Derogatory, disrespectful comments towards individuals are not allowed. If criticizing an idea, focus on presenting concrete reasons as to why that idea is problematic using constructive language.

The professor can also verbalize the intent to make the class a safe space at the beginning of the class and ask students to democratically create ground rules for the space. No matter which way the educator decides to enter into the conversation of creating a safe space, student co-creation of that space is critical to the development and maintenance of safety in the space. Student input on how to conduct a safe space is critical because when students are given the opportunity to co-create their learning environment they get to become comfortable with exercising their real voice in that professor’s presence and they get the opportunity to take ownership of what happens in the class.

Once ground rules for the space are determined, it is the responsibility of the professor to ensure all students and the professor adhere to the rules throughout the semester or school year. In the safe space, the instructor may find themselves taking on more of a discussion facilitator role, unless the instructor turns that role over to a student and quietly observes the conversation. As a discussion facilitator, it is critical the educator does not steer the conversation to a topic or ideological conclusion they prefer. Also it is important for educator/facilitators to model safe, neutral language that would further the conversation so students can learn how to replicate that language.

When creating a safe space, expect heavy emotions and hard confrontations to arise. Despite the fact that safe spaces have been described as cushy, touchy-feely spaces for diverse students in popular rhetoric, in reality they are anything but. When students talk about different topics, especially political, economic or race based issues, they will get into heated debates. During those debates it is important not to marginalize unpopular student perspectives as they may have grains of wisdom embedded within them. While it may be difficult to hear some of the more controversial student ideas, it is still important to hear those ideas out if they are presented appropriately. Hearing out unpopular student ideas give the students who air them the satisfaction of knowing they will be heard even if they disagree with the majority of the group. Also, hearing out students with unpopular ideas offers other students the opportunity to practice offering rebuttals to controversial notions. The trick to maintaining safe spaces during difficult conversations is ensuring students don’t simply use the discussion to complain about issues that bother them. It is important the facilitator (whether it is the instructor or a designated student) pushes the group to discuss possible solutions to the issues so students feel empowered to take actions they deem appropriate once they leave the space.

Finally, in the space it is important not to give too much attention to students who may be trolling other students in the space. Revisiting the ground rules may help curtail trolling. If the ground rules don’t stop trolls it may be necessary ask the student point blank during the discussion if they are trolling the space or to call out their behavior. Asking students to examine their own rhetoric and behavior is vital to maintaining the space because it gives them the opportunity to be self reflective about whether their ideas are furthering the conversation and leading to solutions or simply feeding their egos.

Strategy 3: Invitations and Conversations

While positioning oneself as an ally, it is important to connect with students through meaningful discussions. Those discussions can take place during the classes or one on one during office hours. Initiating conversations during classes may be less challenging than initiating one on one conversations. As instructors we are used to leading discussions by offering up topics, conundrums and questions for discussion. Inviting one on one conversations may be more challenging. To engage in one on one conversations, it is advisable to let the student initiate the conversation. It might seem counter-intuitive to wait for students to initiate a difficult conversation, especially if the professor has already intuited discussing that topic with the student was already on the horizon. In order to get students comfortable with the idea of approaching a professor with a difficult conversation, that professor needs to signal they are available to be a sounding board, even for thorny topics. Signalling can be done through an announcement at the beginning of a course or a casual mention during a conversation are good ways to tell students you are available to talk about complicated issues. During those casual mentions, if the students seem interested, tell a story of how you listened to a student (anonymize your story) and what that student’s outcome was to demonstrate you have experience in listening to diverse students.

One of the best ways to indicate a willingness to discuss complicated topics in relation to the field is presenting alternative pedagogies and theoretical approaches in the classroom. Again, presenting those approaches does not have to indicate agreement with those positions. It does indicate, however, the professor is in conversation with those approaches. Presenting a range of theoretical approaches gives students academic options they can use to broach complicated topics. I have found this approach works for students who want to talk about topics that hit close to home but who want to maintain a high level of privacy.

Strategy 4: Model Codeswitching

Before skill transfer through codeswitching can happen, language, whether discipline specific or culture based, must be translated. Up until this point, there has been an unspoken assumption that diverse students can intuitively learn how to codeswitch as long as they have the vocabulary in each register to describe something. ��Elizabeth’s example demonstrates we cannot assume students will automatically be able to translate language if they have the vocabulary to describe something. To help students who face issues with codeswitching, educators need to conscientiously supply vernacular approximations of our discipline specific language. Once we have given students an example of a vernacular definition of discipline specific words, it is important to model codeswitching between the vernacular and the discipline specific language. Providing vocabulary and demonstrating how to use those terms helps students learn how to connect what they are learning to the language they already possess. Modeling codeswitching and practicing it with students during discussions teaches students how to adeptly communicate within the discipline and how to communicate what they have learned with audiences outside of the field.

Strategy 5: Use Trans-textualism for Genre Transfer

As mentioned earlier, the teaching methods I employed while working with students were trans-textual writing pedagogies. I have had teachers ask me, “What does that mean on the ground?” What that means to me is explicitly describing the components of writing that transfer between genres and which rhetorical components each genre shares with other genres. While we are aware as compositionists that making all of nuances of genres is almost impossible, from the teaching experiences I describe here I have learned it is possible to describe those nuances to the best of our abilities. For example, to help some students transition from writing literary styled pieces to more scientific work, we discussed the parallel behaviors writers employ in both poetry and scientific work, namely observation and recording what is observed. Then we would discuss how those characteristics manifest differently in those two genres- in poetry the observer uses literary devices to convey an image of what has happened, the scientist records bare bone facts to convey what has occurred. Breaking down genres in this way helped students see how the writing and study skills they used in one genre could be used on another if those skills were manifested in rhetoric that was appropriate to the genre.

Moreover, using Freire’s dialogic approach and the Socratic method opens up space for students to articulate their subconscious understandings of genre to during classroom discussions. Each individual comes to the classroom with subconscious understanding of genre based on their encounters of genre in everyday life. Having students discuss the components of a genre without initial input from an instructor opens up space for instructors to ask students how they came to learn those components, if they recognize those components in other genres, how components change from genre to genre and it gives students the opportunity to practice creating transferable components and behaviors in their own writing.

Strategy 6: Make Instruction and Expectations Explicit

There is a lot of debate among compositionists as to how much instruction should be explicit in the writing classroom. I used explicit instruction in all of the previously described contexts. I was explicit about what assignments were given, and my reasons for giving those assignments. While I was also explicit in my description of genres, I was also extremely clear about the fact that genres are ever changing and malleable in the hands of the writer, and I explicitly encouraged experimentation. When students did experiment, I was explicit about the strategies students could go about to make their experiments successful written pieces. For example, one student wanted to write a research paper about their performances and the feminist theories their performances were based on. That student and I worked to make their research paper a genre hybrid that incorporated elements of a research literature review and an artist statement. The key to making that hybrid paper successful was explicitly discussing the components of each genre and talking with the student about which components of the academic research paper and the artist statement overlapped with one another. Once we were able to determine points of overlap, the student worked within those points to create a draft. That draft would have not been created if I had given vague directives to be “creative.”

Explicitness also means not using code words or expecting students to ‘read between the lines” of what you are expressing during instruction. For example, if you say, “be more scientific” when really you mean, “be less emotional,” you are conveying an imprecise and inauthentic message because science and emotion are not mutually exclusive. If we want to encourage students to be their real selves in their rhetoric, we have to model that behavior with real, direct talk that does not sugar coat or dance around the message that is projected.

Strategy 7: Maintain then Augment Student Digital Skills

As we saw with Jimmy Recino’s example, sometimes when the academy integrates digital technology with instruction, deskilling of students can occur. That deskilling can come about as a result of using paper based writing prompts for an online environment, rigid formatting requirements, antiquated digital platforms or not allowing students to experiment with their writing. When students are digitally deskilled in the academic environment, they may see little connection between the work that is done in school and the writing they do elsewhere because the online writing they are doing in school is artificial. That artificiality stunts the transfer of rhetorical skills between contexts.

To maintain student skills, first pinpoint, acknowledge and integrate the skills students bring to the classroom into writing instruction. Allow space for students to teach their classmates and you what they know about digital writing. It is especially important for students to be able to demonstrate their skills because each student will have a different level of digital knowledge that others could learn from. Knowing what skills each student brings to the table will also allow the instructor to take those skills into consideration when developing digital based assignments.

To augment students’ digital skills experimentation, authentic audience and student ownership of projects is critical. When instructors allow students to experiment with their messages with an authentic audience, students have a tendency to be more invested in an assignment because responses from online audiences are immediate. Student experimentation could come about on a group level through creating digital assignments collaboratively in a democratic classroom or individually when a student experiments with storytelling through memes.

When students experiment, we have to give them the space to make mistakes, especially when using an authentic online audience. Once in a while an instructor might be faced with a written piece that makes them think, “I can’t allow so-and-so to publish this! They’ll get a bad reaction from their readers.” What we need to remember is the reader’s reaction is a critical part of the writing process. A writer cannot figure out how to tailor their messages to their readers without having authentic responses they can use to inform their future writing, so making authentic mistakes is a learning process we have to allow our students to go through when they are making their work public.

Strategy 8: Learn the Rules To Break Them

I’ve seen moments on campus where like there’s a proclaimed openness for creativity, but when those moments come, it’s like no, bureaucratically we’re gonna do this way.

- Justin Phan

Often educators claim to want students to be creative with their work but, as Justin points, out often when it comes to making creativity happen, the status quo stands in the way. Educators need to be crafty when finding new ways to integrate creativity while circumventing bureaucracy. To do this an educator needs to learn the rules in their institution that are related to student communication them devise work-arounds they and students can use to project creative messages.

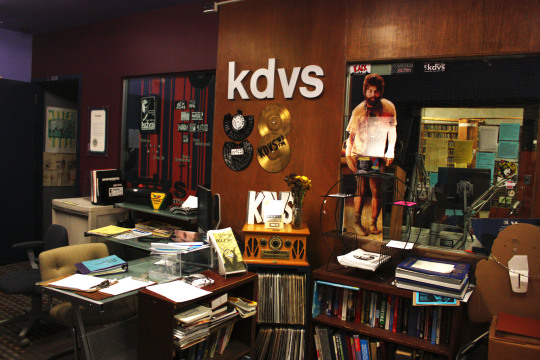

My favorite work around for projecting student voice is the disclaimer. Well written disclaimers are excellent tools for teachers who want to give students the space to vocalize their opinions on public platforms with authentic audiences. For example, in order for KDVS DJs to have controversial talk shows, the studio had public affairs DJs read the station disclaimer that absolved the station and the school from being responsible for student views. Using a disclaimer removes the need for an instructor to censor or even “subtly guide” the messages in their students’ work because the instructor has put the responsibility where it belongs- with the writer. Typically, when students are faced with taking responsibility for what they will publish in the public sphere, they will apply more care when creating a draft.

0 notes

Text

Voice 2.0: When Acquiescence Becomes Resistance

Conclusion Part 1

All of the students who have been showcased here agree they have used different voices, authentic and inauthentic to their true selves, to navigate the paths of their academic careers. These students defined the differences between their “real” voices and their CZ voices in terms of whether they were speaking their own truths in light of their cultural paradigms as an act of resistance to monoculture or whether they acquiesced to institutional conventions and ideas in their rhetoric. What is interesting about these findings is the fact that using standardized American English was not the defining factor for an inauthentic voice- the ideas behind what was articulated by students using standardized English was how students defined a voice as inauthentic.

This finding builds on previous findings in composition literature about the projection of diverse student voices in that it demonstrates the current generation of students may not have the same anxieties or difficulties about acquiring academic English the previous generation of diverse scholars had. For example, Mellix (1998) and Gilyard (1991) both struggled with the tensions between gaining skills in academic English while maintaining African American English as the main connection to their culture. Rodriguez (1982) lamented the loss of his mother tongue, Spanish, and his cultural identity as a result of acquiring academic English. All of these authors, like Villanueva when he suggests jaiberia, discuss voice was in terms of the degree or ways in which a diverse individual acquiesces and assimilates to the mono-culturally based institution through the use of a particular language or dialect. Othering was involved in the experiences of these authors; each one of these authors saw standardized English as the language of others, white Americans, not one of the dialects of their homeland.

In the current generation, there is a shift in paradigm. Like the previous generation, the current generation of diverse youth understands standardized English is the currency that will pay the tolls on their journey. These youth recognize the populace they will encounter in urban, digital and global markets are extremely diverse, with languages and cultures as unique as their own. Moreover, many of the people they encounter will speak some form of standardized English as well. Like Lu’s daughter (1998) who moved seamlessly between the language of home and school, the current generation of students code-switch with ease to fit different contexts, with no inner turmoil about demonstrating alliances to specific cultures through speech acts. This lack of turmoil may be because multiculturalism and multilinguism are valued more than they were when the previous generation scholars came into their own because of the changes that came about in response to civil rights activism. As a result, the current generation does not feel pressured to relinquish their ethnic, gender or sexual identities. Instead of feeling ashamed of not fitting the monocultural norm, these students cherish their unique backgrounds and work to respect the backgrounds of others.

The current generation of diverse students seems to be moving towards a culture of hybridity that does not view standardized English as a language of a normalized other that, in turn, casts their language and ways of being as abnormal. Instead, the youth view standard English as just another way to communicate their ideas. Removing the pressure of conforming to white and often male based heteronormative identities frees up student energy to focus less on getting the mechanics of standardized English down pat to ensuring their messages are crafted well in standard English and any dialect or language they choose to use. When those messages are crafted well they generally demonstrate students’ desires and demands for institutions to assimilate some of their culturally based ways of being and knowing on some level.

Students’ push for hybridity in academia is a step further than what the previous generation of compositionists wrote about as they progressed on their journies as scholars. However, the current generation’s approach is reflective of the practices and examples put forth by “radical,” social justice activist scholars of the previous generation, like Gloria Anzaldua and Angela Davis. I put radical in quotes here because at the time these and other activist scholars’ ideas were put forth they were considered radical, but since then those ideas have been normalized. We in academia like to joke that no one reads our work but the reality is, at least among diverse students who are focused on social justice, the current generation is reading the literature and utilizing what they have learned from it in their day to day behaviors and in their scholarly research.

This shift has occurred among youth due to the realization that surrendering to the institution or working within the bounds of it’s so called power, even on a small, subversive level, is a relinquishment of personal power. The fact of the matter is institutions need our acquiescence, our silence and our insincere messages to perpetuate its oppressive practices. In changing our vocalized messages we have already surrendered to oppression.

In addition to talking back to institutionalized oppression, the student work that comes about as a result of using “radical” discourse offers the possibility for student originality that goes far beyond what could be considered “abnormal discourse” (Bruffee, 1992). Bruffee argues “abnormal discourse sniffs out the stale unproductive knowledge and challenges its authority (p.31)” by undermining our reliance on “normal discourse” or what I call “institutionally derived” discourse because to call such discourse normal makes all other discourses pathological. When students merge their academic acumen with novel ideas that stem from their unique backgrounds, original, progressive knowledge is created. Because of the synergistic relationship between academic investigations and unique paradigms, students may project messages that go against everything we’ve learned to be “truth” during our own journeys of institutionalized education. In the following sections, I will overview all the strategies described in this dissertation that came about as a result of the research I did so more teachers can welcome voices of resistance into their teaching practices.

0 notes

Text

Diverse Voices in The Disciplines

Part 2: Justin Phan Challenges the Academic Status Quo through Alternative Ethnic and Gender Rhetoric

(Photo source: UC Riverside Ethnic Studies Department)

Justin Phan exudes a grounded seriousness that draws a teacher in whether they are in front of the class or meeting with him one on one. The attention in Justin’s eyes never wavers, even when talking about topics most students perceive as boring. When teaching, I always felt certain Justin was working to absorb as much of the information that was being co-created during the learning process in each moment during class. That said, I deeply respected Justin because he is not the type of student to take the information that is presented at face value. Justin always critically analyzes the rhetoric around whatever is being discussed so he can have the ability to critically respond to the mindsets and concepts that underlie that rhetoric with his own ideas. Justin’s willingness to articulate his findings on the eurocentric rhetoric that surrounds diverse peoples, gender, and the concept of race gives Justin a number of opportunities to practice translating his culturally based ideas into academic rhetoric through codeswitching in safe spaces.

As the son of Vietnamese immigrants, Justin seeks to understand how the confluence of militarism and post-colonialism impact gender, race and nationalism in the Vietnamese diaspora. In terms of the current composition literature on students of immigrant descent, Justin Phan would be labeled an Asian ESL student, despite the fact that Justin has an extraordinarily high English competency in everyday conversation and in his writing. However, when Justin began college as a biological sciences major he did not feel confident as a writer. For Justin, writing seemed to focus on grammatical rules and formulaic approaches to composing a message. Justin claimed he would spend hours working on the mechanics of a page trying to get it “just right” while missing the opportunity to focus on honing his message. Justin admitted:

“I felt like I wasn’t good at writing. I felt like for me for a while I didn’t really, like, do any reading or writing. It was something I was kind of worried about, and I was kind of taught it as a formula, usually with the five paragraph thing and try to do your topic sentences and stuff. And so I tried to write that for a while. I always saw writing as just like plugging in and following that formula that they taught us, not really thinking about what kind of lessons or what kind of message I'm trying to convey. So I think really early on, maybe that’s just the way that writing was taught at high school.”

Justin also had trouble with striking a balance between being conversational or being formal in his work because of his perceptions of the constraints of academic writing. Justin perceived the genre to be more clinical and emotionally detached, so he had more difficulty with academic writing. Much like the other students featured in this research, Justin’s identity informs the topics of his papers. Despite that fact, Justin definitely felt a split between his academic and personal voice.

So now I’m having trouble, well how do I know if it’s like academic enough and how do I know if it’s too personal?...

I think it’s still all part of me, because I feel like, I believe that people function differently in different circumstances. And so when I need to write for an anthro paper, I might take on more of this objective voice, while also trying to intervene... while at the same time I’m writing for one of my feminist study classes, those things are, in a sense, given, the idea that subjectivity shapes how you talk about things. So I feel a little more at ease reflecting on personal experience[in a feminist class], than I would have said about a sociology class, where a professor might say, like, anecdotal evidence is not evidence.

In this quote we can see when Justin determines a particular discipline does not value the same evidence he does, in this case valuing storytelling as evidence, the split between his academic and scholarly voice occurs. While Justin admits he understands people communicate differently in different circumstances, he also still has issues switching between the rhetorical stances of each discipline.

Justin went on to describe how all that changed. When Justin got to college two things happened to him concurrently. First, Justin gained awareness of the academic dialoguing process that occurs perpetually across theories, theorists, and texts through his first university classes.

“...over the years I started seeing reading and writing as more of like a dialoguing process. So I started imagining the books as people that I’m just talking to, or like they’re talking to me, and eventually I started thinking about, like, citations as like, well, if you’re in this room with all these people, you are just trying to make a point and have this person, well this x person said this and let them speak for a while, and, well, ‘this’ is what I'm trying to get at by having them speak. So it seemed, eventually I think I saw writing as more of a performative process, where it was kind of like there’s a production side to it, where you’re producing a piece of work to convey a particular message, and it’s also how you are trying to frame it as you’re going along with different points and putting yourself in dialogue.”

In understanding the dialoguing process, Justin realized the way to interject himself into that dialogue was through writing. While this seems like a no-brainer for most of us academics, the fact that Justin came to this realization independently is huge given the fact that most diverse students see the ideas and approaches that are a part of the academy as set in stone with no entry point for new, alternative ideas.

The second thing that happened to Justin was during his first years at UC Davis was much more personal. Justin completed what he describes as a “racialization process,” meaning he was designated “Asian” by the school which is problematic because that term was developed through a Eurocentric paradigm and doesn’t reflect the uniqueness of each cultural group that originated from the continent of Asia. Being lumped in this way led Justin to question and talk back to the stereotypes that were foisted upon him and others who would be designated “Asian” by white monoculture. Justin reported:

“prior to coming to Davis, I didn’t really closely identify as being an American... You know I came into the world with my family, right? They didn’t call themselves Asian Americans; they called themselves Vietnamese, because we’re Vietnamese immigrants—folks from Vietnam, but here in the US. So there’s a family culture that was there, and there were ways that school tries to categorize me in particular way based on the historical legacy of racism. So you know that I’d be, I think part of the reason I was in honors classes was because I was a quiet Asian student who did homework. You know, like, I think that’s part of it...the ways that I interacted with being Asian American was different I think, before coming to Davis.”

The racialization process Justin began to undergo in high school reached a critical point when he started attending Davis. Justin argues the academic institution racialized him and other diverse students by lumping them into groups according to monoculture based “assumptions of positionality.” Assumptions of positionality presumes an individual has insider knowledge of a particular group or represents a particular group because they identify with that group or have characteristics of that group. The assumption of group representation may occur despite the fact that the individual may not identify themselves in the same way, or there may be a body of group foundational knowledge that individual may not have access to.

Justin went on to describe the different types of Asian students that get lumped into identities that are pre-constructed by monoculture based rhetoric based on assumptions of positionality:

“There’s international students, students who face things differently, folks that are breaking down model minority stuff, and saying that not all Asians are wealthy, hardworking, super good at math and science. And I think that coming from the Bay area, I was able to play into that [stereotype] in many different ways...”

What made different Justin’s college racialization experience different from his high school experience of being racialized were the student-run community centers on the UC Davis campus. Becoming involved with UC Davis’ student activist community raised Justin’s awareness about talking back to and resisting the legacies of racist monoculture. That resistance includes rejecting the model minority stereotype that has been projected onto Asians by whites because that stereotype was created to denigrate other ethnic groups.

When describing being described as “Asian” by an institution and responding to institutions through activists networks, Justin says:

“it’s a new racialization process coming to Davis, and being part of networks that would try to challenge those logics institutionally, that try to categorize that all Asian folks are similar, or saying that ‘This is what Asians are like,’ based on the funding grants, or stuff like that. I know that people are working on a grant right now, so if you are at school [that is] twenty-five percent Asian serving, then you can apply for this grant. So like I think for me, it was coming here and seeing activists being like, ‘Wait we’re not all Asian in this particular way that you’re trying to construct us.’”

The type of critical response to academic schemas and systems diverse, radical scholars construct as Justin describes here brings to light the amount, or lack thereof, of nuance researchers and administrators bring to the table when describing and working to serve diverse students. Justin questions the assumptions embedded in these types of identities because they have been pre-constructed by a racist system. Superimposing assumptions of positionality on groups of people can lead to faulty decision making based on limited data and activist acts in response to, or in accordance with, the negative outcomes of those decisions, whether they be administrative or pedagogical outcomes.

Coming to Davis, there is system networks of student centers, academic departments that really try to politicize these Asian ideas of race and try to really kind of combat racism or combat other forms of oppression on campus. And so being part of those networks of people, who consider themselves radicals or anti-oppression activists like stuff like that, really shifted and made me think about the world completely differently, cause ‘politics,’ ‘radicals,’ and ‘Asian-American’ I would never use in a sentence prior to coming to Davis.”

Justin learned to talk back to and reach beyond the limitations of monoculturally constructed identities when he joined student groups that presented alternative pedagogies that integrated ethnocentric and gender-based ways to construct knowledge. The alternative pedagogies of the student groups introduced Justin to active facilitation between diverse groups of people and differing theoretical frameworks. Justin ended up combining his awareness of the ongoing academic conversation with the theories and approaches he learned in activist spaces. Justin then transferred the practices of facilitation from those activist spaces to his reading and analysis of texts when he became a humanities major.

Justin went on to describe how he came to see writing as a “performative process” that put himself “in dialogue” with the authors he read, which is a critical, well-documented skill advanced writers possess. Justin also came to see the differences between facilitating dialogues among real people and acting out imaginary dialogues between authors and their theories.

“I started seeing facilitation as an important part to writing, so if you were to, it’s kind of like facilitating a conversation of different theoretical frameworks or different people who have different opinions, and trying to get at some kind of consensus with it. Rventually I started realizing that consensus isn’t necessarily what I’m trying to do...”

Justin’s reading practices revealed to him that the theories and ideas he works with do not have to concur with one another, leading him to get comfortable with ideological conflict and ambiguity. When ideas talk back to one another to create ideological conflict, that conflict opens up space for new ideas to challenge old concepts and bring more nuanced approaches to an issue.

In Loco Parentis: Parenting Other People’s Adult Children

One of the main on-campus issues Justin wanted to talk back to was what Justin described as a parental tone and approach the university takes to its students. Justin calls UC Davis’ approach to managing its students “In Loco Parentis”, or the institution acting as a stand in for the student’s parents and family. To support his claim, Justin examined the rhetoric in a number of UC Davis publications using anthropological approaches. One of the textual data sources Justin used to demonstrate the patronizing parental voice the school uses to speak with students was, coincidentally and ironically, Aggie Voices. I did not discover that fact until I read Justin’s first completed draft, so I did not influence his analysis of the blog in any way.

Justin’s results demonstrated UC Davis’ publications frequently evoked the image of family by referring to the campus community as a family in multiple publications. After constructing the university’s familial ideal, the institution worked within that family framework to hand down rules and discipline, much like a parent would, to students. Justin argued UC Davis’ approach to communicating with students and the community at large negated the students’ autonomy and rights as unique individuals with their own families and cultures. Moreover, in invoking a parental stance the university refused to see students as adults who are, more often than not, paying for their own education in one way or another. Positioning the students as adults would confer more power to students since they would be seen as they are - consumers paying large sums of money for the university’s product, not children who need discipline and management.

Justin found the conversations we had where we triangulated ideas and delved into the political in a private safe space was most helpful for his papers. I never interjected my own personal politics but I did present different sides from different theoretical approaches (I used ideas from linguistics, sociology, discourse analysis, feminist theory and decolonizing pedagogy) and in regards to each on-campus political issue to help Justin sort out his ideas. However, I was the second person Justin sound boarded his ideas with. First, Justin engaged in these and other topics with his mentor, Professor Mama. Professor Mama, who Justin described as having extensive experience with activism, encouraged Justin in his quest to merge his activism-informed ideas with his academic analysis. Professor Mama encouraged Justin to complete his research using a research journal so he could chart the development of his thoughts and findings. In both his conversations with Professor Mama and myself, Justin got to practice code-switching between the language of the academy and the world of activism effectively while analyzing complicated, political topics related to diverse people in the academy.

Engaging thorny topics, like criticizing the rhetoric of the institution where one works or studies, a tricky strategy because talking about politics or other complicated ideas can be explosive for an instructor’s career. That said, these conversations have to happen so students can see how a more seasoned academic code-switches between the languages of different spaces, so they can see how an academic positions their ideas and so students have the opportunity to practice code-switching and positioning in a safe space. Conversations like these have to be done in such a way that the educator doesn’t come off as partial to any particular idea or cause. The conversation also has to be initiated by the student and co-navigated by the student and educator. The initiation of a political conversation by the student indicates the student feels the educator is trustworthy enough to approach about with the topic in addition to being knowledgeable about it. It might seem counterintuitive to wait for students to initiate a difficult conversation, especially if the professor has already intuited discussing that topic with the student was already on the horizon. Professors hold high levels of power over students, whether we like to admit it or not. If a professor initiates a difficult conversation, that initiation could lead to the student feeling manipulated or led in their academic pursuits.

Again we see how trust between the educator and the student, particularly when it comes to the student trusting the educator with their deepest ideas, impacts how the student crafts their message. It is important to remember the student is being initiated into a discipline by the instructor, so the instructor is the “face” of the discipline, so to speak. Student encounters with the faces of a discipline will determine how the student characterizes the discipline itself and whether the student believes their ideas will be engaged, validated or even accepted by a discipline. Justin’s example provides a sharp contrast to Elizabeth’s example. Justin’s non-academic rhetoric was welcomed and engaged by his mentor, so he felt he had a point of entry into his discipline. In contrast, Elizabeth’s mentor rebuffed her language and ideas, so Elizabeth did not feel welcomed into her discipline, despite the fact that other individuals in the discipline would be interested in her ideas. In these students’ examples, we can see how much power we educators have as individuals when it comes to ushering in more diverse students into our disciplines. The fact of the matter is we have a lot of power on the individual level, more power than we typically give ourselves credit for. Seemingly monolithic disciplines are made up of individuals, namely us scholars. When we criticize our disciplines for not being more diverse, we’re criticizing ourselves. We have to take into consideration the fact that our disciplines may not be more diverse because we as individuals have not welcomed diverse ideas and peoples. Perhaps we have inadvertently upheld the status quo by teaching and doing things the way they have always been done because it is safe or because it is all we know. Justin’s relationship with Professor Mama demonstrates disciplines grow and evolve when the participants of that discipline are willing to grow and evolve. Professor Mama saw Justin had something to teach, something she and her discipline. In inviting a student to become a teacher, Professor Mama fueled Justin’s passion for research while opening space for the discipline of Anthropology to evolve.

0 notes

Text

Diverse Students in the Disciplines

Part 1 : Can Westernized Science Learn From The Native Paradigm? Elizabeth Moreno’s Experience

There has been much discussion about the importance of ensuring diverse students learn the ins and outs of discipline-specific language (Bazerman, 2003; cited by Bawarshi and Reif, 2010) and the political and linguistic complications surrounding that learning process (Villanueva, 2011) in the field of composition. In those discussions, there have been lingering questions as to whether the acquisition of discipline-specific languages and genres are tools that usher students into assimilating the prevailing monoculture or whether using that language is a necessary skill diverse students must acquire to initiate themselves into the knowledge generating society.

The UC Davis McNair scholars grapple with the tensions between those two polarities every day in their research and personal lives. They walk the fine line between becoming scholars who investigate their topics rigorously while maintaining their culture based paradigms. I took a two-pronged approach when responding to these students’ needs. I taught the basic components of academic journal article writing with a Hallidean approach by sticking closely to the standard characteristics of the genre and showcased how the sections shifted according to discipline as best as I could. I balanced that prescriptive approach by putting student knowledge and collaboration at the forefront, especially when I did not know the discipline well, like in the case of mathematics proofs. Before any lecture on the genre, I had students define what the genre meant to them or what rhetorical components they noticed in the genre. Starting with student knowledge building bolstered students’ agency because they were given the opportunity to access, display and validate the knowledge they had in their collective consciousness about genres. Activating that part of students’ consciousness also made students metacognitively aware of the psychological level genres spring from and work upon.

While the students and I collaboratively built knowledge on how academic writing manifests in their disciplines, I also encouraged the students to experiment in their work with genre-mashing and by playing with vocabulary. I gave the students who were brave enough to experiment with genre-mashing semi-explicit information on how to execute their work by describing how the different components from each genre could compliment one another, how they could negate one another and how to move between the rhetorical moves in each genre on the sentence and section level as they combined components. For example, I guided one student to create a journal article that integrated components of the artist’s statement to describe the theoretical foundations of the performances they produced for their research project.

Using the experiences of the McNair scholars students, this final results portion works to adds to the discussion surrounding diverse students and discipline-specific language by challenging both sides of the divide. The experiences of Elizabeth Moreno and Justin Phan demonstrate the acquisition of discipline-specific language does not necessarily lead to assimilation. Moreover, their examples demonstrate how diverse students move beyond simply acquiring discipline specific rhetoric to reconfigure genres by integrating their culture based paradigms with discipline-specific language. Integrating their own rhetoric into their discipline-specific research allows these students to talk back to their disciplines and the assimilationist rhetoric that is embedded in it.

However, I found students could only accomplish that goal when they are adequately supported by the educators they work with. Below I will describe how Elizabeth and Justin integrated their culture based rhetoric with their research, some challenges they faced and which teaching strategies were best suited for these students. I will also examine the circumstances that lend themselves to assimilationist practices of voice suppression in the disciplines by focusing on the experiences of Elizabeth, a veterinary student of Native descent who felt excluded from the language of her discipline.

(Photo Source: Elizabeth Moreno’s Facebook Page)

There is one in every class. The student that flies under the radar, who almost doesn’t get as much attention as they should until towards the end of the semester when the teacher finally realizes, “Hey, this student is freaking brilliant.” The instructor kicks themselves a little bit for fawning over the smarty pants or being overly annoyed (and attentive) to the trouble makers. But they don’t waste too much time because they want to use every remaining moment of class enjoying that quietly brilliant student.

That student is Elizabeth Moreno. Initially, it was hard to see how smart Elizabeth was because I’m not sure she realizes how smart she really is, so she doesn’t project an air of extreme confidence in her intelligence like most gifted students will do. Elizabeth was kinda quiet at first during the summer writing intensive I held my first year with McNair. As time wore on she gained confidence, testing out more vocabulary words, offering up fun jokes and basically keeping the mood light by putting on Spongebob Square Pants during lunch breaks after we had been writing all morning.

Elizabeth impressed me with her willingness to experiment with vocabulary and phrasing in her writing. During the course of our class, Elizabeth diligently tried out each strategy in the 10 Step method, which led to more comprehensive discussions on how the shades of meaning each word can shift the meaning of a sentence (or simply not fit) even if a synonym of that word could be used appropriately. I appreciated Elizabeth sparking off those conversations because many of the other students were not willing to take the time to investigate the meanings of words then experiment with those words in their work. Elizabeth’s conversation sparked the curiosity of her peers and led them to consider how word precision can make a difference when it comes to clarifying one’s messages.

The speed and ease with which Elizabeth wrote also blew me and her classmates away. No one expected Elizabeth to be the second person to complete the McNair Journal Article in the cohort. Elizabeth’s article on increasing mare prolactin levels using artificial lights was sophisticated and Elizabeth seemed to really enjoy completing writing overall. So when Elizabeth volunteered to participate in this research foray, I was really excited to learn more about her writing process. I didn’t realize going into the interview I was in for a lot more surprises.

Going into the interview Elizabeth expressed a paradoxical situation. She had a fair amount of confidence in her writing but she felt she didn’t communicate her ideas well, which surprised me because I always found Elizabeth to be a clear communicator in her writing. Elizabeth felt her verbal communication was impeded by stuttering because her mind was typically a few steps ahead of what she was saying and she was always searching for the most erudite to say things, which she described as “nerve-wracking.”

Elizabeth’s constant search for the right words is definitely affected by her ESL status. Although she is highly fluent in English,as a woman of Yaqui descent Elizabeth reported she has trouble translating ideas from Yaqui to English. That trouble is not because of a lack of vocabulary on Elizabeth’s part as a woman who speaks English as a second language. The issue lies in the fact that Yaqui paradigm is completely different from Eurocentric ways of seeing and being in the world. For example, according to the Yaqui, the world is composed of five worlds, the flower world, the dream world, the night world, the desert world and the mystical world. The goal of Yaqui religious practices is perfecting these worlds and mitigating the harm that has been inflicted on these worlds by human beings. The Yaqui ways of seeing the world is reflected in the ways Elizabeth would like to approach veterinary science:

I get the feeling that most people, and just humans in general, like to think of themselves as being above animalistic tendencies, and we have to change certain aspects of the environment around us, so that we can have a better life sort of thing… things like changing, physically altering ourselves, our bodies, even though what you know how inter-created everything is. Essentially it’s the way it’s supposed to be, it has a reason, and it might not be the most attractive design, but it works. Yup, some humans just want to think that, like they want to distinguish themselves above animals and the environment and just nature in general. Whereas the Yaqui and just other Native Americans, it’s not just the Yaqui, it’s like a partnership with the mother Earth. And going with the flow of how the nature systems are working, kind of like take it as it comes kind of thing, like things happen for a reason. Didn’t rain because well it didn’t rain, and we have to figure out, we have to change ourselves to, you know, not to try and change the Earth, just so we’re happy, without thinking about what the heck, what implications it can have on the ecosystem and things like that. But that’s kind of what I feel when it comes to the mindset of the world between Western thinking versus Native American thinking…

Elizabeth reported that she is aware her Yaqui mindset affects how she communicates with people. She finds she has an easier time communicating with people who can see the world from this alternative perspective, but not so well with people who are firmly entrenched in the western mindset.

Elizabeth’s writing trajectory may have been affected by the complications of having to navigate translating between two mindsets. Elizabeth described her writing learning trajectory as being praised early on in elementary school for being extremely detailed with the images, but having that praise turn to criticism in high school when her AP English teachers characterized the descriptions as “fluff.” Elizabeth reported she had a hard time adapting to that change, saying:

Probably this is probably where my stubbornness came in, cause I was always the good writer, so I was like, “What the fuck,” you know, “What are you talking about? How do you not understand what I’m trying to say?” …apparently the rules of communication had changed since elementary school.

Elizabeth went on to describe struggling with communication overall during and after high school, but paradoxes still lingered. For example, she reported going to her high school AP English teachers to clarify their understandings of the arguments in her papers. Elizabeth’s teachers initially docked her paper grades down for not being clear, but upon review with Elizabeth, her arguments came across. When Elizabeth completed first year writing in community college, she received yet another contradictory message about writing. That instructor criticized her for not being detailed enough and for not focusing on her writing. Elizabeth conceded she was not focused at that time, that she had basically stopped caring about her writing and went through the motions to get credit at that point. Elizabeth claimed by the time she completed the writing courses that were required for her degree, she felt writing probably was not that important for her as a person in the sciences. Elizabeth’s lost interest in writing during that time could be attributed to the conflicting feedback she got from writing teachers as she shifted across each stage of learning. A coherent message about all of the components that constitute good writing, which could have included advice on how details can contribute to building a powerful argument, probably could have helped Elizabeth feel more confident about using her strengths in image making to communicate her arguments more effectively.

The theme of ineffective communication leading to going through the motions arose again in Elizabeth’s interview when we discussed her McNair Research Project on artificial light and mare prolactin levels. Elizabeth revealed that she had problems getting her mentor to hear her ideas about animal behavior and that their conversations led to Elizabeth having anxiety about communicating her ideas with that professor throughout the course of the program. Elizabeth’s anxiety was especially pronounced because she struggles with depression and PTSD as a result of previous traumas. In the following example, Elizabeth recounts when her mentor insulted her using academic language when Elizabeth tried to put forth an idea on pregnant mare behavior:

Elizabeth: Um, let’s see. Although I, for instance, I can understand how people say, “you can’t talk to animals,” it’s just, we don’t communicate the same way they do, but there’s still ways of kind of at least limiting down what they are trying to tell us. So in this case when we were trying to find a project for me to work on, we were talking about how no one has really figured out how the mare or the female horse knows that it’s pregnant. We know how it happens chemically, but we don’t know how they know. And I think I mentioned something like, “Why don’t we just ask them?” I was kinda leading to that. And she’s just looks back at me with this, kind of like, you’re so stupid face. It’s like, “but they can’t tell us.” And I’m like, “duh they can’t freaking tell us, but we can at least find a freaking way.”

Kenya: Right. And they can tell us by the way they act, and there’s horse whisperers, right?

Elizabeth: Yea, you know? And she finishes that topic with, “Yeah, we’re gonna have to work on your critical thinking skills.”

In this example, Elizabeth’s mentor hinted Elizabeth lacked the intelligence to create research on animal behavior, an insinuation that effectively shut down Elizabeth’s desire to elaborate on what she meant by “asking” a horse how it knows it is pregnant. During the interview, Elizabeth’s rhetoric displayed she did have the aptitude to describe how a researcher could “ask” an animal questions. Without much prompting on my part, Elizabeth elaborated on the idea of communicating with animals saying:

“… there are certain plants that animals kind of gravitate towards, cause it’s kind of alleviates the symptoms. So we know something about a plant and what it does, what effects it seems to have on the animals, then we can, it’s like listening, it’s like hearing animals say, like this is what’s wrong with me, I have a freaking upset stomach, that is why I’m eating a bunch of grass, so I can just puke it out. Like that’s what I need, and at least they get to tell you, instead of you just, at least they have the chance to kind of tell the veterinarian, like, “This is what’s wrong with me.” Cause that’s what I’ve always heard growing up. Like, “it’s hard being a veterinarian versus a doctor cause you can’t talk to an animal.” And so there was that idea, and then another idea I had, it’s not quite veterinarian medicine, but it’s just like how animals and humans can kind of work together better, how they can kind of communicate better.”

Elizabeth’s method of communicating with animals by backtracking the cause of their behaviors, like in the example Elizabeth presented of analyzing the foods they eat, is scientifically testable. If the research questions and methods were formulated with precision by building on the knowledge that is already in the veterinary field and expanding upon it with ideas that are based on Elizabeth’s Yaqui knowledge, Elizabeth could get answers to her questions. Unfortunately, Elizabeth was stymied from developing research around her ideas simply because her mentor was not prepared to hear Elizabeth out by asking Elizabeth to elaborate on what she meant by “asking the animals.” “Asking” could have taken the shape of presenting a mare with a range of herbs to determine if the mare knew it was pregnant based on the herbs they ate as a research project Elizabeth did not feel sure if her mentor’s response felt aggressive because her mentor was actually aggressive or whether she was overreacting due to her PTSD. Regardless of her mentor’s intent, they never continued that line of conversation again. More troubling, Elizabeth felt anxiety in relation to every communication she had with that professor, even simple emails.

After reviewing the entirety of the interview, it is my opinion that there is a strong possibility Elizabeth’s mentor was in the habit of not listening to Elizabeth at all because of disinterest on her mentor’s part. That lack of attentiveness could have led to the cutting remark Elizabeth reported. I glean that possibility from Elizabeth’s description of her professor’s attitude towards Elizabeth’s research topic and the McNair Scholar’s program itself. Elizabeth reported her mentor was not really interested in animal behavior, which was Elizabeth’s focus, so they were, in Elizabeth’s words, “already at a loss there.” Elizabeth also claimed her mentor didn’t see the McNair Scholars as a fellowship program because her mentor always referred to it as a scholarship, despite Elizabeth’s protests to the contrary:

“…that one I can’t say I freaking miscommunicated, ‘cause I told her. I was like, “No we have, we get paid during the summer, we have to basically act like researchers, and you teach us how to do it,” you know?”

Elizabeth claimed her mentor saw the work Elizabeth did for the program as juvenile, which led to tension between them when it came time for Elizabeth to complete her research conference presentations and the final journal article. During the creation of Elizabeth’s research conference poster, for example, Elizabeth’s mentor criticized her images, the colors she used and other graphic details. Elizabeth’s mentor also criticized her for being “overly analytical” and having a “one track mind” in her research. Tensions between the two even continued after the completion of Elizabeth’s paper. For example, The McNair scholars director and I had to step in and contact Elizabeth’s mentor to get her paper approved as the professor did not readily communicate with Elizabeth. As a result of that tension, Elizabeth stopped engaging with the questioning phase of the research process and simply piggybacked off her mentor’s work to complete her McNair project.

Elizabeth did concede her mentor taught her how to write the introduction and hypothesis portion of a research paper for their discipline, which she did find beneficial. When I asked Elizabeth if her authentic self wrote her paper, she plainly responded, “No… That was someone else.” Elizabeth went on to reveal her real self had not shown up in any of her writing in school. She agreed with my assertion that if a student was passionate about their work, their real selves would appear. However, the opportunity for Elizabeth’s real self to compose had not arisen because the real Elizabeth was too unconventional for the academy.

Elizabeth’s case was a difficult one for me because after the interview I came away with the idea that Elizabeth had needed more instruction on how to couch her ideas in rhetoric individuals working from a western paradigm could hear them. In other words, she needed more practice with codeswitching and she needed to execute that practice in a safe space before testing it on professors. During the interview, I asked Elizabeth:

Do you think if you had said something like “well maybe if we observe their behaviors to get some cues we can see how they understand they’re pregnant”, do you think she would have accepted something like that?

Elizabeth: Um she probably would have…

Unfortunately, I came to this realization too late. Elizabeth was in the first cohort of students I worked with at McNair, and I only taught those students over the summer, so I didn’t have the opportunity to work with her on codeswitching like I did with the following two cohorts. When Elizabeth seized on practicing vocabulary using the ten step method I presented, I took it as Elizabeth wanting to improve her vocabulary when in actuality it was a sign Elizabeth wanted to improve the way she communicated her messages in academic English. What she needed was the ability to structure her sentences in the moment, not more words that could potentially muddy her message.

Looking back on Elizabeth’s example I have also come to realize how much new information is lost when diverse students are not able to pre-package their ideas into rhetoric that is easily digested by higher ups in their disciplines. Elizabeth’s ideas were sound but the halting way she presented them, partially due to confidence issues, partially because of difficulty in translating between the Yaqui and western paradigms, obscured the value in those ideas. Elizabeth could have submitted her findings in the peer-reviewed Journal of the American Holistic Veterinary Medical Association if she had been encouraged to pursue her research. For Elizabeth, encouragement could have taken the shape of more listening or asking follow-up questions like, “what do you mean by ‘ask’” questions that could have pushed Elizabeth to flesh her ideas out.

That said, even if Elizabeth presented her ideas in a better way, would they have been heard? In Elizabeth’s case, we can see how miscommunication between diverse students and professors can happen due to issues on both sides. Yes, diverse students may need more practice in codeswitching to academic speech. However, professors from Eurocentric backgrounds may need more practice with mindful listening and conversation engagement to build student trust and confidence. Conversation engagement is not just asking questions or asking students to elaborate on their ideas. It also includes putting one’s own ideas about the world on hold to allow students to present their own ideas without the fear of being judged. Judgment and feedback are two completely different things. Judgment is the projection of value on an idea. Feedback, on the other hand, gives students something to work with based on what is known in the field and generates ideas on how to go about discovering new knowledge based on the research interest of the student. The student trust that arises from conversation engagement and feedback leads to more opportunities for students to build their code-switching abilities. Having multiple opportunities to engage in the feedback process brings students to the point where they can synthesize their culture based ideas with academic rhetoric, thus adding to their respective discipline while circumventing total assimilation. What Elizabeth got from her mentor was judgment, not feedback, which led to the shutdown of her authentic voice because she didn’t perceive her mentor to be a safe person to entrust her ideas.

In Elizabeth’s case, we can the perpetuation of the status quo and assimilation into standard genres is not simply the result of teaching formulaic approaches to the academic journal article genre, nor is it the result of fitting ideas into academic rhetoric. It is the result of enculturating diverse students into the normalization of idea and voice suppression through microaggressions and the outright dismissal of novel, culture-based approaches that have not been couched in academic language.

I could be said that Elizabeth’s mentor discouraged her line of questioning to protect her from making a research misstep. Indeed, sometimes instructor dismissal of student ideas is done under the premise of protecting students from making mistakes in their work or in their careers. We instructors may think we are saving students time and effort if we discourage them from an idea. Maybe we are, maybe we aren’t. Maybe the idea of “protecting” students is just a patronizing way of saying a diverse student isn’t capable of facing challenges in the field. Maybe that protection is just a continuation of the “protection” others projected on us when we wanted to do ambitious research but were told to tone it down for the sake of our careers. Maybe that protection stems from the fear of having a student venture into territory that is filled with knowledge that we, as “experts,” cannot comment on.

Whatever the case may be, the bottom line is as educators it’s not our job to protect students. It doesn’t matter if we agree with their ideas or not or whether we think their ideas are foolish or not. History has proven time and time again some of the best scientific discoveries have come from “foolish” ideas, so it is completely plausible our students may be touching on new discoveries. All that matters is if we tell them in a concrete way why their ideas may or may not be doable. The trick is to present students both sides of an issue and to let them decide on their own whether to move forward. We can also plainly present them with the possibility of challenges they may face so they can develop their own solutions if they decide to move forward with their ideas. We can also help them work through the solutions to those challenges to the best of our ability. As we can see in Elizabeth’s case, kibbitzing a seemingly stupid idea is an injustice to the student and the field. Giving judgment, even supposed well-meaning judgment, instead of constructive feedback silences a student’s voice and stops the creation of new knowledge in the discipline.

Silencing oneself to fit into a culture is the cause of assimilation, whether it is through rhetoric or through behavior. The written generic format has little to do with that assimilative process and code-switching doesn’t do it either. The written genre-based work is just the final product that documents the silencing that had already taken place during the rhetorical and behavioral exchanges between the discipline’s inductors and inductees.

However, when a diverse student is enculturated into their discipline by a mentor who encourages culture based vocalization in conjunction with critical analysis, the genre documents that as well. The following student, Justin Phan, is a prime example of how diverse students are currently gaining mastery over written academic rhetoric while also infusing their own culture based mindsets into their disciplines. Justin’s example will demonstrate this cross-pollination can only happen when diverse students are adequately supported by their instructors and academic communities.

0 notes

Text

Context and Audience’s Impact on Voice

Analysis of Student Interviews

When I originally developed this research, I wanted to do a textual analysis of all the student volunteers’ writing to determine whether their voices shifted according to discipline and context. That desire evolved as I conducted interviews with the students, which led to the development of one central textual analysis and my development of understanding voice by listening to the students’ feedback. I found as I analyzed their interviews the things students had to say about the contexts in which they composed their writing and rhetoric and how their personal histories influenced their voices was much more interesting than the texts themselves. I also found there were interesting parallels between two pairs of female students in each of the remaining contexts I will examine, The Diversity Forum and the McNair Scholars program.

In the following section, I’ll describe in detail what students revealed about how their personal histories, cultures, their self-knowledge and their level of discipline-specific knowledge influenced the manifestation of their authentic voices in their academic work. Here I will focus on the students I worked with on the Diversity Forum before moving on to the analysis of the McNair Scholars’ feedback.

Listening as Rhetorical Instruction Tool