Text

CURTAINS

Seventh grade might just be the zenith of adolescent misery. Silly and childish but cunningly cruel, these kids are no longer cheerful and plucky nor are they settled in young adulthood. With each hunched shoulder and downturned glance, seventh graders show the world just how completely misplaced they feel. When my daughter, Jasper, was in seventh grade, she came home from school one day having just been dropped by her group of friends, suddenly, with hurtfully choreographed precision through simultaneous texts, and without apparent reason. She collapsed in my arms, limp and sobbing, telling her story through heaving gasps. There was a new, never heard before pitch in her voice, concordant with the agony of her four-year-old strep throat and her ten-year-old broken arm, but more textured and complex. Her sound was so full of emotion that it stunned me to the core, and exposed within me fresh, untouched territory on the surface of my heart. She dried her eyes and looked at me, asking without words for the assurance that she would be okay. I wiped a last tear from her cheek and told her she would get through this, that this is life, and that there is darkness and light in each moment. I chose my words carefully, shaping them as best I could in a way that she could hear, knowing that too much doctrine would lose her, and that most of all if I were to show her my new heart place, throbbing and raw, that it would be too much. So I covered it up, drew a dark cloth over its angry redness, and what remained was what she needed, a calm and steady light shining towards a path of resilience.

The moment did not last, and she withdrew from me and went to her room, headphones on, door locked. The next two weeks were a rollercoaster of ups and downs, a dream-like, darting story that I could barely patch together with frayed bits of conversation with Jasper and late night reading of the texts on her phone. Each day, she came home from school alone while her friends gathered together somewhere else. I spoke with my mother daily, and during my conversations with her, I wept. She’d answer the phone and my chest would swell with ache, my eyes overflow with tears. We spoke of the betrayal I suffered in seventh grade, how my friends, without cell phones or texts, choreographed a sudden, devastating betrayal. As we talked about my decades old hurt and Jasper’s fresh new one, my mother drew back the covering of her heart and described to me the pain she felt as I came home from school day after day, my suffering almost unbearable for her to see. Those friends that were swept up by the intoxicating whiff of adolescent power play are now beloved and close to me. But in seventh grade, my mother described, they hurt me deeply and revealed within her a first-felt heart place that she covered up as she looked into my thirteen-year-old eyes to let me know I would be okay.

My mother was with me when the radiologist shut the door after my mammogram and told us that I had breast cancer. I had felt a lump and was worried so my mother cancelled her plans to come along to my appointment. The world collapsed in that moment, dizzyingly spinning and rushing, deafening drum-beating heart and wave-crashing blood, windowless room and searing florescent lights. I turned to look at my mother and saw in her eyes the flash of a new heart place opening within her, blindingly bright, but in a moment it disappeared and was replaced by a love so solid and strong that it carried me through a year of chemotherapy, surgery, and radiation. She was there every single moment, holding my hand as the healing toxins poured into my body, smiling at me as I woke up from surgery, two breasts and two ovaries lighter. Not once did she pull back the curtain to show me her heart place, not once did she share with me her pain.

“It hurts so much, mom, I can barely stand it,” I said to my mother on the phone, driving to pick Jasper up after yet another call from school, the quiver in her voice revealing that the stomach ache she complained of to the nurse was actually more heartache caused by her peers.

“Tell me about it,” she said, ”How about watching your daughter go through cancer,” she said lightly, a dance we can now share, one with moves that sharpen with every year that passes since my diagnosis.

“Oh mom,” I said, shocked by a surge of understanding, “That must have been so very hard for you.” In that moment, I saw what I could not see when I was a daughter, suffering and scared, wrapped in the arms of my mother.

“Yes, it was hard, but I always knew you were going to be okay.” She had closed the curtain again, but this time it was a translucent, breezy cloth so that I could see the contours of her heart place, the ragged valleys and bottomless seas. In this moment we shared something new, another light in the darkness, the struggle of seventh grade and the terror of a daughter’s cancer, and the extraordinary power of a mother’s love.

0 notes

Text

To the Man Who Made My Little Silk Robe

Thank you, sweet soul, for your gift. How did you know just what I would need? I know so little about you, but I think about you each day as I pull my silk robe out of its matching drawstring sack and slip it on. For weeks, I’ve driven over the Golden Gate Bridge, still glorious every time, silk robe tucked into my purse, to arrive at UCSF’s breast cancer center in time to find parking for my daily 11:20 radiation appointment. I know the drive well, and after five months of chemotherapy and a bilateral mastectomy I can daydream the whole way from home to the hospital.

I was told by another patient that your mother was treated for her breast cancer at UCSF. You then designed and anonymously donated these beautiful robes to be given to women facing radiation treatment. I know very little else about you, however I imagine you to be impeccably dressed, at least some part Asian, slight in body, and gay. Blame the silk and “Project Runway” for much of this.

Beyond that, it is clear to me that you are someone extraordinary, and that you must have watched and listened with love and intention as your mother journeyed through radiation. Was she startled by her reflection in the women’s changing room mirror, even though the hair on her head and face had been gone for months? Did she stare curiously at the smooth stretch of skin where her breasts once were, numb to the touch and divided by two long scars mapping the path from armpit to armpit?

Perhaps she showed you the rectangular burn on her chest and the small, painful blisters that emerged by the end of her treatment. She must have described the way her skin was irritated by the course fabric of the hospital gown she was cloaked in each day. How did your mother feel when she realized she would need to completely remove this gown for each treatment so that the radiation techs could carefully arrange her body, naked from the waist up, on the narrow, cold table? I imagine you went to great lengths to design a robe that was simple for a woman to gracefully slip off just one shoulder and breast while remaining modestly covered everywhere else.

You picked the softest silk fabric, creamy and cool to the touch, and in a range of patterns to suit a variety of tastes, each one undeniably feminine. I sit with my cancer sisters in the women’s radiation waiting lounge, each of us wearing a beautiful silk robe made by you. We cluck about at each other’s pattern choice and share tips for tying the one-size-fits-all-remarkably-well sash. Kate, a shockingly young woman with an appointment time just before mine, chose a bold geometric pattern that reminded her of “a Gucci.” Mai, a Chinese grandmother who is the first person in her family’s memory to get any kind of cancer, chose the same fabric that I did, swirls of pink and white on black, like a Japanese kimono. And Carol, the African-American woman in her fifties who came to radiation each day with her mother and cried loudly in her arms on her last day of treatment, chose a shimmery black fabric covered with purple and gold overlapping crescents. We each wear your robes like they were designed specifically for us. You somehow knew this would matter very much.

Since my diagnosis nine months ago, I’ve stumbled upon angels, often when I’ve least expected it – people I have met during my countless trips to the pharmacy, virtually through friends of friends of friends, or while captive for long hours in the infusion center. There is the woman I met for lunch with four other breast cancer warriors, all young mothers, who wisely told us, “I could be depressed and have cancer, or I could just have cancer. I choose just cancer.” And the voluntarily bald woman who works at my local grocery store and described to a terrified, just-diagnosed me the utter freedom and sexiness a woman can feel when the yoke of hair vanishes. Or my new but beloved friend and accomplished editor who reached out to invite me under her capable wing and helped release a ripe, new writer voice within me. You, maker of my little silk robe, are one of my angels, for you have made me feel understood and beautiful and so very human at a time when my body often feels like the lab materials for some grand experiment.

I hope you and your mother are well past this journey now, safely on the other side of treatment, radiation burns faded and hair grown back. I wish you both a long chapter of survivorship seasoned with new perspective and fresh inspiration. For the remaining weeks of my radiation treatment, I will wear my little silk robe with gratitude for the man your mother raised and in celebration of the extraordinary potential of a generous heart.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Long Game

I want to introduce you to hormone therapy, the sneaky, quieter member of the breast cancer battalion.Hormone therapy is patient and wise, with eyes on the long game, fighting with brains not brawn. It slips in slyly after its meathead cronies, chemo and surgery, make their big, braggy, bloody show of assault. It steps right over the detritus of scar tissue and destroyed GI lining in search of any microscopic, hidden remnants of disease still standing after the one-two-punch.

Hormone therapy settles right in for a ten-year stay, its job simple and clear. It is there to sweep up any estrogen that remains in the body, which surprisingly amounts to a significant measure even when the ovaries are removed or no longer functioning. Estrogen-positive cancers feed on the powerful hormone and can’t grow and spread without it. As a now ovary-less 42 year-old who is post chemo and a bilateral mastectomy, I’m taking the more effective, often harder to tolerate version of hormone therapy called aromatase inhibitors. Each morning I swallow one tiny yellow pill that blocks an essential enzyme needed for estrogen production, which, from a cancer-fighting perspective, is just what we’re hoping for.

I imagine these rogue cancer cells, those with the strength and intelligence to have survived thus far, withering away from hunger and thirst, their estrogen receptor sites like cracked, parched desert. It seems to me a miracle of science, the result of billions of dollars to sustain laboratories and trials so that we can manipulate the chemistry of our own bodies. Because of the promise of hormone therapy, women rejoice when pathologists report that their cancer is estrogen-sensitive, a.k.a. curable even if chemo, surgery, and radiation fail.

We estrogen-positive cancer women are urged to take these pills with gratitude and an unwavering commitment to our survival. We are told that these pills cut our chance of recurrence in half. We are told that the side effects which range from annoying to miserable must be tolerated if we choose life.

So most of us do. We tell ourselves that the debilitating bone and joint aches are a sign that the medicine is working. We accept that the drying up of our lady parts at an unnaturally young age is what we must accept if we are to reach ripe, old womanhood. We peel off layers of clothes as each hot flash reminds us that our hormone therapy is skillfully battling on. And we try not to think of our bones that might be eroding without estrogen to keep them strong, and our hearts that might congest because of hormonal manipulation.

It is an impossible choice to consider life with such compromise vs. an increased chance of cancer winning the game. So I’ve decided it’s not a choice, that it’s a path without options. It just is what it is, my body’s journey through this one life. And if it needs to be sweatier, dryer, and creakier than I had once imagined, than so be it.

0 notes

Text

12 Ways to Support a Breast Cancer Warrior

Given that one in eight women will develop breast cancer at some point in their lives, chances are you’ll have the opportunity to don your pink ribbons and stand by in support of your friend, sister, mother, or daughter. Breast cancer is highly treatable if caught early, but the treatment (chemotherapy, radiation, surgery, and hormone therapy, or some subset of these four) is unthinkably challenging. Breast cancer warriors have little choice but to fight long and hard, and in the process face an enormous physical and mental battle.

I've been a breast cancer warrior for eight months, chemo and surgery behind me, radiation and hormone therapy around the corner. My battalion is made up of loving, brilliant, powerful, and hilarious soldiers who have made this journey one of thriving, not just surviving. They have fed me, kept me organized and clean, encouraged me daily, spoiled me with surprises, and made me feel strong and sexy, even when each and every hair on my body had disappeared.

Science has proven that cancer patients who journey through treatment with support have an edge regarding survival. Below are twelve ways to be a breast cancer support soldier – the difference you will make is beyond measure.

1. Bring the Good Stuff: Love, laughter, support, affection, companionship are all essential. Avoid probing questions unless she invites you in. Leave your own fears at the door.

2. Rock the Bald: Take her to get a henna tattoo on her beautiful bald head. She will feel like an exotic queen.

3. Do Her Dirty Work: Come over to her house and clean it up. Organize her pantry and do her laundry.

4. Avoid the ER: Label her 30+ pill bottles with red sharpie on the lids so she doesn’t swallow a laxative when reaching for an Immodium. Wash your hands whenever you’re close by.

5. Run the Show: She will need meals delivered, kidcare, rides to treatment, errands run, and general caretaking. Take the lead role and help her figure out just what she needs. Then organize and rally the troops.

6. Shower her with the Little Things: Send her texts to tell her you are thinking of her and that you love her. Drop flowers or a pair of big earrings to compliment her henna’ed head by her door. Send a card or gift in the mail, sing a song on her voicemail. Do this often, all the way through her treatment and beyond, and don’t expect a response.

7. Keep Her Cozy: Send her fuzzy socks, candles, and hydrating lotion. Make her a quilt filled with art and love. Before her surgery, send her soft pajamas that open up in the front.

8. Run off with the Rugrats: If she has kids, take them with you as often as you can. Fill this time with joyful noise. Return them with a smile and a spotless report.

9. Heal with Humor: Liberally send lengthy viral jokes and raunchy or adorable (depending on her taste) youtube clips. Share her medical marijuana and have a chuckle fest. Spend a day on the couch with her watching funny movies.

10. Fill her Plate: Bring nourishment to her doorstep. Sign up for the meal train, check in with the lead support team to see if she’s eating kale salad or ice cream shakes. Family food needs might differ, so plan to feed multiple palates if necessary. Deliver in disposable containers.

11. Reach out with Retail: Take her shopping to get to know her new body. Honor what was lost and celebrate what is new. Visit the lingerie department when she’s ready. Bring champagne.

12. Love her Up: Understand that at times she may feel a raw and indescribable fear that is hard to comprehend. Do whatever she needs to help her through it. She will find immense comfort and healing in your love.

1 note

·

View note

Text

BATTLE ON

According to some, the year after cancer treatment is harder than the year of cancer treatment. Long days of nausea and fatigue fade into memory, food again tastes normal, energy returns, and life resumes. However, I’ve been warned by fellow cancer survivors that a depression sets in, a feeling of loss and an emptiness that easily slides into fear and worry. No longer are you tucked in the bosom of the unrelenting care of your doctors; rather, they’ve moved on to other patients, leaving you a bit bruised in the way of an ex-lover. You’re left with the onco-version of the post-break up coffee date --- a simple check in, without the sexy scans or MRIs, just a blood test followed by a conversation. “How are you doing?” the doctor will ask, as you gaze at her and wonder if she’s happier now that you’re no longer going steady.

As each of these rather dire warnings of future doom was delivered to me, staunch defiance and denial rushed in, even though it seemed rather suspicious that people kept offering the same omen. I was deep in the hell that is chemo and there was no way I was going to look outward to the misery ending only to find myself feeling some horrific emotional version of worse. I’m not that type of person, I told myself and anyone who asked, I’m the type that moves on and doesn’t look back. Next year will be about new adventures, long bike rides, new boobs, and a strong, healthy me!

At the end of chemo, my oncologist, who I’m finding is as outstanding as her reputation suggests, brought up the subject in her indescribably unique way. “Next year,” she said, as she palpated my collarbones to search for any suspicious lymph nodes, “will be hard. It can feel like you’re off on your own and it can be emotionally challenging.”

This was an unfortunate development. Not ready to admit defeat, I asked, “Do all of your patients struggle like this?” hoping to hear something like, “No, not at all. In fact, special, strong patients like you feel nothing of the sort!”

“Yes.” she said instead, with certainty. “But some are more able to cope with it than others.”

Ok, I thought, it’s going to happen to me, but I’m going to be a super-coper, and I will feel just a tinge of worry then jump back on my mountain bike with my perky boobs and ride off into the sunset. Plan was set. You can imagine my disappointment when days later, I felt what I understand now to be my first of a series of terrifyingly sad moments -- sickening, gut-wrenching aches of fear and overwhelm. The Chinese describe it as looking at your life from the bottom of a well, trapped and out of control with no foreseeable way forward. In these moments, I look directly into the eye of the worst of this whole thing, the version of the story that ends with me succumbing to disease at an unthinkable age. If I hold my gaze too long, I melt in true despair, rubbed raw by the immensity of what I’ve seen. So I look away, and I think through the facts and the odds that are hugely in my favor, and I fill my body with fresh, vital breath and close my eyes and rebalance. At times, I reach out to someone I love and ask them if I’m going to be ok. “Of course you are,” is the response and it’s exactly what I need to hear. It is a practice and a journey, exhausting and self-strengthening all in one.

I have moved into a place of acceptance that these moments will come and with each one that passes, I trust that I will have the strength to face the next one. I’ve been told that as time passes, the moments become less frequent and potent, and I’ll hold on to that promise. The cancer war is fought on multiple fronts by an army of body and mind, and sometimes the burden is on the mind to carry the heavy bulk of the battle. I can’t help but hope that life-altering gifts will come of my mind’s struggle through and past these moments: a bone-deep understanding that most of what we worry about doesn’t actually matter, an actionable belief that each day is a gift, and a desire to live a harmonious life.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

BEFORE THE AFTER

I’ve prepared for other highly significant days in my past, our wedding day, significant professional moments, the births of my kids, my father’s funeral this past spring. However, heading into my mastectomy/oophorectomy surgery I felt a unique mix of trepidation (6 hours under the knife and so many parts of me changed), excitement (I’m a new experience junkie and I’m getting new boobs), and a tiny, squeaky fear of dying. Feeling freshly energetic after the end of chemo, I decided I needed to prepare for surgery with some intention.

I went on several long walks with close friends, a practice I learned long ago watching my mother’s daily, life-nourishing walks with her best friend. I sat twice with a very wise and skilled practitioner named Susan who led me through a series of guided imagery experiences, and then practiced these mind/body exercises at night with Susan’s recorded voice leading me forward to a place of understanding and calm. I scheduled one Turkish body scrub to rid my skin of its dry, chemo-singed layers. I indulged in two massages with extraordinary healers trained to work with cancer patients. I wrote and wrote and, with the extremely capable and loving support of three dear writer/editor friends, polished my last blog piece, Dear Body - Love, Mind and sent it out for publication. Friends offered to take our kids for the night before surgery and through the whole next day, setting my mind at ease that they would be tucked away and cared for.

I had some really important conversations with friends and family. Most poignantly, I pulled both of my kids aside, separately, to talk with them about what was to happen on surgery day. I talked with them about the procedure, how it would happen, and just what would be removed and replaced in my body. I then engaged each of my kids in a conversation about my ovaries and breasts, and the role that they played in our joined lives, the sweet, cozy magic of breastfeeding and the minute eggs that became their little selves. These conversations were distinct for my seven-year-old boy and nine-year-old girl; each required a tone and tenor matched to their age and personality. However, they both collapsed with pleasure into the stories I told, folding into my arms, faces full of child love. And both agreed without question that it was time for these parts of me to go.

All of these exercises and conversations prepared me well. Ready and Steady became my mantra, and off to surgery we went early on the morning of December 22, bags packed, skin sanitized, and spirits at peace. We worked our way through paperwork, nurses, residents, and a mudslide-induced traffic delay for my primary surgeon, until at last I lay in my gurney, IV placed. As the oozy surge of anesthesia sent me off, my last gesture to my mom and Andy was two thumbs up with a big smile on my face.

What followed was a series of quite remarkable events that made an already unusual day rather extraordinary. Very soon after my thumbs up dive into anesthesia, the hospital’s power went off. Yes, that’s right, the hospital’s power went off. Apparently a generator kicked right in, but at that point, the hospital chief decision maker ordered all surgeries that hadn’t been started to be transferred to another campus several miles away. I was deep in a snoozy, feel-no-pain zone, however no cut had been made, so the anesthesiologist pulled me out of my deep sleep in preparation for the transfer. At this point, chief decision maker decided there was actually enough power to perform six surgeries, a couple of which were underway, and mine was selected as one that would remain at the Mt. Zion campus. So I woke up, only to be told through a gauzy haze that my surgery would continue under generator power, to which I replied, “OK,” and disappeared back into drugged sleep.

All proceeded without a hitch. I woke up six hours later in a dark and oddly empty recovery room, and was somehow inspired to start singing “Bye, bye, Boobies” to the tune of Bye Bye Birdie. My next words were to ask, “Was it published?” in reference to Dear Body-Love, Mind, which was in fact published that day on the amazing blog, Momastery. It seems that many thousands of people read and shared my post while my body was undergoing the very transformation that inspired the piece. Very powerful indeed.

The surgery is now behind me, phase two in my kick-cancer’s-ass game plan. I am recovering well but slowly, as my incisions heal and body forms anew. My journey from before to after has felt smooth, even with power outages and recovery pain. I am tremendously grateful for the care I received at UCSF, the astonishingly brilliant surgeons I entrusted with my life and the extraordinary nurses and caretakers who guided me in and out of the surgery experience. And, I am grateful for the preparation I could never have managed without the support of my universe of wise, beloved family, friends, and healers.

0 notes

Text

DEAR BODY - LOVE, MIND

Dear Body,

As we march together toward the big day, I thought it might be helpful to huddle up. We’ve been joined as one for a little over 42 years and, I’d say, have been a pretty phenomenal team. I realize, however, that I haven’t often spoken directly to you with intention, while you talk to me pretty much all the time through sensations of pleasure, pain, fatigue, hunger, thirst and desire. So here goes, my first formal letter you.

I want to start with some appreciations. Thank you for healing the scrapes and cuts of our childhood and for tolerating the soccer goalie dives that left your hipbones raw and bloody each August through December. Thank you, body, for being so very strong, for climbing mountains, swimming seas, and running one damp D.C. marathon. You must have been relieved when I entered my 20s and took up yoga; we became really close then and you got to sweat, purge, stretch and strengthen without pummeling your joints and connective parts. Most recently, you rode up mountains on our bike, pumping like a machine, rarely complaining and almost always ready to push harder.

Thank you for making our babies; for serving up two perfect eggs and growing those delicious children inside of you. Thank you for knowing just what to do during the long nine-month stretches, for opening up to let those babies out, and for making more milk than any one infant would ever need. I’m so grateful that you didn’t become diseased until after those wonderful babies were born, and until they grew old enough to manage this journey with resilience and compassion. I imagine you had to fight pretty hard to do so. Thanks, body.

And, some apologies. I’m sorry, skin, for that tanning booth chapter in high school. I’m sorry, feet, for each time I forced you into narrow high heels. To a body who needs a good nine hours of sleep per night, I apologize for the years 1998 – 2003. I’m sorry, body, for the times I wished parts of you were smaller, leaner, higher, smoother, tighter, or otherwise different. And poor, sweet hair, I’m sorry for all the chemicals. It’s no wonder you bailed on me.

It has been six months now since we sat in that small, windowless room to hear that the thickened area on your right breast was not actually an infection; rather, it was stage two breast cancer. Since that surreal moment, I’ve learned so much about how you function and the millions of miracles that happen within you every day. I’m in awe of the complexity that allows us to thrive, the delicate balance that is essential for health, and the power of science to fight disease. I find myself craving a deeper understanding of the intricacies of your inner-workings and of the various phases of treatment. I wish I could somehow be the one to care for you, that I was twenty years younger and could go to medical school and be your doctor.

I want you to know how sorry I am that you’ve had to endure liters of toxic chemotherapy pouring through your veins, but body, let’s be straight with each other: you kinda turned on me. It’s not your fault – the DNA we inherited was mutated, leaving your breast and ovarian cells primed to become carcinoma. You’ve handled the chemical onslaught as best you could, often speaking to me with unquestionable clarity and commanding, “Get in bed and stay there. Get up only to pee.” I listened, dear body, and we made it through.

So now we head into the next battle, one where parts of you will be removed. There’s too much risk that your mutated breast and ovary cells will yet again become cancer, so surgery we must face. I hope that together we can let go of these parts, grateful for the miracles they performed, mournful for the loss of them, at peace with the reality that they must go.

I’m sorry that three surgeons will cut into you, marking your beautiful skin with scars and scooping out pounds (yes, pounds) of tissue. I ask that you’ll graciously accept our implants, working to fend off infection and heal smoothly. I know your back will appreciate the lighter load, and your shoulders will love riding around bra-strap free.

It’s you and me, body, heading into the next unknown. I promise to honor your strength and beauty and to nourish and care for you as you heal. Here’s to us.

Love,

Mind

___________________________________________________________________

Dear Mind,

Thanks for the letter. You’re overthinking things. Our new boobs are gonna be awesome.

Love,

Body

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

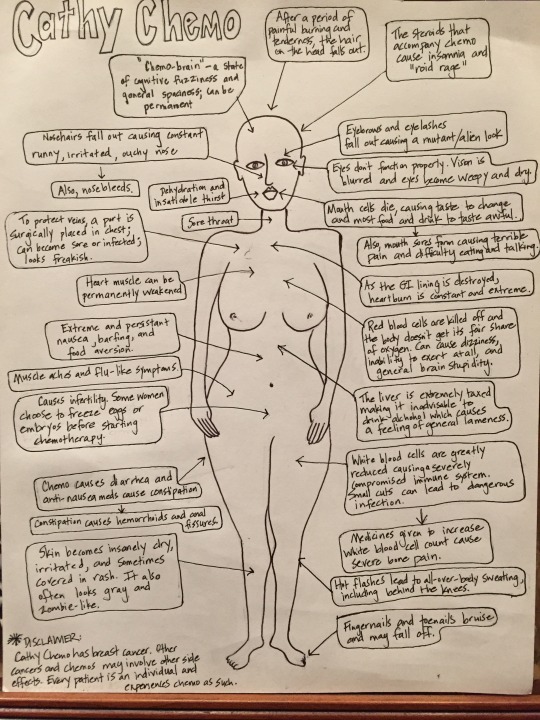

CATHY CHEMO

I have been itching to draw lately, and also feeling the need to process the last five months of chemo now that I'm done with that chapter. Tonight, I ended up sketching what has turned out to be my avatar, Cathy Chemo, see illustration below. Making Cathy was the perfect way for me to gather together all of the moments between now and last July 2 and see it all on one page. I look at Cathy with a mixture of wonder, horror, and amusement, because really it's just so very absurd!

1 note

·

View note

Text

MY GIRLS

I haven’t put on a real bra since my diagnosis. For me, a real bra is a thing of armor, constructed with large swaths of hefty material, shaped for full coverage and held together by thick, sturdy straps. My bras have no time for playthings like lace or sheer material. The most my bras can manage is a swirly flower embroidered into the canvas-like fabric, an attempt at feminizing that ends up feeling more like a doily on an antique table. Beyond their aesthetic shortcomings, my bras leave me feeling constricted, pinched, and agitated. Lift and stabilize they do, but at quite a cost, and after my diagnosis, I stopped wearing them altogether, opting for absurdly incapable but deliciously comfortable thin, wireless bralets. Something shifted and I was no longer able or willing to tolerate any discomfort in the bra department, and I somehow stopped caring altogether whether my girls were properly placed and held.

When I first learned that I had breast cancer (bad news) I very soon connected the dots and realized my heretofore burdensome bosom would be forever changed, reduced, and lifted (fabulous news!). My early breast cancer conversations with friends were filled both shock about my disease and merrymaking about my future new boobs. Why not? I’ve been lugging these things around for decades, proud that they did such a stellar job serving their one actual purpose (my kids nursed heartily, often, and for a solid 18 months each), but always burdened by their bounty. I’m an athlete, and have been stuffing my breasts into ill-performing sports bras since high school soccer. Bathing suits are impossible, and there are whole categories of clothes that are simply off-limits (spaghetti straps, anyone?). To imagine a life in which I’m freed from this bosomy burden is indescribably exciting, a life where I no longer need to wear my matronly, function-forward brassiere (rumor has it I won’t actually need any brassiere), where I can run freely without first securing all parts, and where I can throw on any dress on the rack, regardless of straps, coverage, or cut.

All of this is to say that for months now, I’ve been more than ok letting go of my upper lady parts in exchange for a pair of high, firm, hassle-free new ones. But now, as I actually face the surgery, just 22 days away, feelings of fear and loss are creeping in. What will it feel like when they’re gone? Will I miss them? Will my new pair ever become part of me in the same way? The skin will remain, the nipples will be gone (and eventually tattooed back on), but the tissue inside, down to the muscle below, will be scraped away so that my BRCA2 mutated breast tissue won’t turn on me yet again in the future. I’ll emerge from surgery with tissue expanders underneath my chest muscle, placeholders for the silicon implants that will eventually be there. What will THAT be like? What will it feel like to have these foreign pieces inside of me? Will I feel the seamless sense of whole that I have always felt in my body?

People get joints replaced all the time and don’t tend to mourn the loss of the failed knee or hip and wonder how the prosthetic will effect feelings of identity. A knee is not a boob, however, and a boob is not a hip – neither play such a central role in femininity, sexuality, and identity. Women all over the world choose to have breast implants, and I imagine feel lucky to have the chance to change their bodies in that way. Perhaps it’s the absence of choice for me, that my surgery is not the elective type that I’ve been saving for for years and finally had the time, money, and courage to do; rather it’s the next step in a treatment plan that leaves me pummeled, weakened, and in ways, disempowered, because there are no choices to be made, just acceptance of what lies ahead.

So for now, I’ll leave my mega-bras in the drawer as I make my way to December 22. I hope that my surgery will bring me a much deserved and joyful change in my body, and I will also honor my loss for what it is and must be.

1 note

·

View note

Text

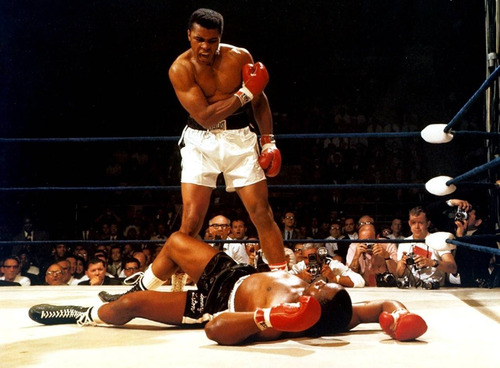

KNOCKOUT

Tomorrow is my last chemo infusion, at least the last of this series of 16 mind-melting, body-pummeling, hair-killing, nausea-inducing, energy-zapping chemo infusions. I began this chemo journey perched upon a sturdy foundation of determination, physical fitness, and general kick-ass mojo. I told my oncologist to give me everything she’s got, that I was not scared, and that I was ready to do all that I could to beat this cancer. I had been riding my bike to the top of Mt Tam, trail running, and balancing it all with a regular yoga practice. I was cooking and eating a healthful, mostly vegetarian, nutrient and flavor rich diet, rarely including sugar or processed foods. My mind was vibrant and charged, and I felt healthy, invincible, full of physical power, and ready to fight.

Twenty long weeks later finds me celebrating a slow walk around the block as a solid daily workout. Meals consist of anything I can get past my mouth sores into my fickle stomach, often a bowl of ice cream, a milk shake, or a variety of white, starchy, nutrient-less foods. My mind, its edges woefully dulled by chemo, can barely follow my Facebook feed. Yoga makes me want to vomit, running is an absurd impossibility, and my bike hangs pouting in the garage like an abandoned lover.

When you look at this remarkable juxtaposition you might think that chemo won the battle, that I end this journey defeated. But there lies the staunch irony of chemotherapy. This bizarrely toxic and horrific potion that has stripped me down to the basic elements of being alive (as in my heart is still beating and I’m breathing so I must be alive, but at times it’s hard to tell) has beaten out the enemy, so I actually won! Maybe this is how boxers feel at the end of a really hard fight -- face bloodied, nose broken, ribs cracked, but mighty glove lifted in victory.

The thing is, this thing ain’t over! Not even close! In about two weeks, I should feel relatively normalish (as if I know what that means anymore) for a couple weeks as my body and blood rebalance in preparation for surgery. And we’re not talking about just any surgery, we’re talking about the kind of surgery that takes a frightening number of hours (I actually haven’t asked for the exact number because I’m afraid to know), that involves the removal of several body parts, and that requires not one, not two, but three surgeons. And then, as if my poor poisoned and carved body needs more assault, we move onto radiation. I learned today that my doctor team feels 100% sure that I will need radiation, zapping any shred of hope that I was holding on to that I might escape that chapter. I was actually pretty forlorn to hear this, as radiation can wreak havoc on the reconstruction process, and my visions of a new and perfect rack have lifted me right up and out of my chemo blues when such lifting was needed.

But alas it is what it is – a saying that has become my mantra. This is what it is – there is no other way around it but to walk through it one absurdly horrible step at a time. There really is no choice but to endure the torture that is my treatment’s bedfellow, and whenever possible to feel gratitude that it’s all possible for without each of these essential pieces my cure would become harder to achieve.

So, with my own bloodied but mighty glove, I hear the bell ring to end round one, I huddle in my corner to rehydrate, wipe the sweat from my eyes, and prepare to head back out to face my opponent again.

0 notes

Text

NADIR

This week was the second week of my first round of AC, aka Adriamycin Cytoxan, a chemo cocktail that’s been used for years with known benefits (great) and side effects (awful). I had been told that the nausea would likely subside after about a week, and that I should feel tired but almost normal the second week. As promised, the first week brought intense and rather unrelenting nausea, finally fading on day six or so. At that point, however, I didn’t feel normal at all. I felt physically pummeled and emotionally distraught, my expectations of feeling decent for a few days of reprieve shattered. I wasn’t sure why I was feeling so awful or which medication to take to help, so I decided to call my oncologist.

Within an hour or so, I got a call from Jeanine, one of the two nurses who field all chemo-side effect calls from patients. Her voice warm and nurturing, enough to trigger a little girl tightness in my throat, asked me to describe my symptoms.

“Well, I feel absurdly tired, like I can’t really get out of bed and my body feels like lead, and my mouth is filled with sores so I can only drink liquids, and I tried to walk up a hill and I couldn’t breath and had to stop like ten times, and every time I stand up I almost faint, and I feel like my heart is in my ears I can feel the pounding so loudly, and my skin itches all over, and I’m so achy I feel like I have the flu.”

“Aw, I’m so sorry to hear that,” she replied, “A lot of those side effects are due to AC, but it also sounds to me like you’re anemic. You’ve actually been anemic for some time, but you’re now symptomatic so I bet your hemoglobin counts have fallen to a point where we’d like to give you a blood transfusion. Would you be comfortable with that?”

Blood transfusion? This sounded rather dramatic and creepy. Jeanine went on to describe the procedure, which, I learned, did not involve draining all of my blood and replacing it with someone else’s as I had thought. I would receive two small bags of packed red blood cells and some saline, and my cell-needy blood would all stay in tact. The whole thing would take 4-6 hours and they could schedule me to come in in two days.

“Is this normal?” I asked, “I mean, is this something that you expected to happen?”

“Oh yes, this is much to be expected. You’ve been on taxol and carbo for twelve weeks, both of which can make you anemic, and AC really takes a toll. And, you’re now at the nadir of this AC cycle, the low point, so it makes sense that you’re feeling so awful.”

The nadir. The lowest point in the fortunes of a person or organization. The lowest level, all-time low, bottom, rock-bottom. Yes, it seemed I had reached a nadir, of the AC cycle, and of my chemo course. No longer running with friends or really doing much that requires standing or moving, the chemo seems to be A. doing it’s job (the tumor is no longer visible on MRI!) and B. kicking my ass. What was a few hard days in each cycle seems to have morphed into day after day of feeling rather awful in ways too many to keep track of. My chemo brain makes it hard for me to follow the movies I watch with kids. Seriously, I had to ask Jasper repeatedly to explain the plot turns in the Book of Life (not a complicated script…). The mouth sores make eating, already challenging because of nausea and confused, fickle taste buds, almost impossible. I wake up in the morning feeling like I’ve been up for three days.

The bright side of the nadir is that it’s the bottom, and the only place to go is up. Since Jeanine oriented me at my own personal multi-leveled nadir, things have indeed improved, and I’m now able to look down at that rock-bottom spot from someplace better. First, I got the transfusion, hungrily accepting two bags of blood from two donors, wondering what prompted them to donate that day (Blood drive at the office?) and sending gratitude into the universe. The next day I woke up feeling better than I have in months, the world in finer focus and an energy in my body that reminded me of life before chemo redefined what it means to “feel good.” I still peter out midday, but the paralyzing aches are gone and each day I’ve felt periods of feeling able to function relatively normally.

And, as important as my new super-powered blood is the support that has rushed in. My cousin Michelle took a week off of work to be with me for my first week of AC and she spent all week caring for me, sorting my pills, cooking protein-rich soft foods that I could stomach and get past my mouth sores, reorganizing my linen closet, and holding my hand. Michelle left and a few days later my sister arrived from Maine to help me through AC #2, bringing her immense sister/auntie love.

I arrived at my kids’ school one morning a few days ago, beaten down, exhausted and miserable. The first friend I saw offered to arrange indefinite daily playdates for seven year old Dylan who needs play and exercise after a long day at school. The second friend I saw offered to put together a meal train of kid-friendly dinners for the next couple of months. After just one walk to school, I arrived back at home, climbed into bed, and felt myself lift away from my nadir, transfused with love, support, and community.

And that’s how this has been, this remarkable cancer journey. Science and doctors and infusion bags attack my tumor. Anti-nausea medication and packed red blood cell bags ease my side effects. And all along have been my people, surrounding me with the most essential layers of support -- meals, stunningly thoughtful gifts, patient companionship, so much laughter, walks (both slow and speedy), youtube clips to make me laugh, books in the mail, candles, lingering visits to my couch or bedside, emails and phone calls filled with advice and care, long and beautiful hugs, thinking-of-you texts and cards, and so much more, every day. It is what sustains me, what pulls me out of my nadir, buoyed by the best that humans can be.

1 note

·

View note

Text

GAMETIME

We’re going to play this blog entry Breaking Bad-style. I’m going to paint for you a picture of the end scene, the surprising, ironic hard to patch together finale, and then we’ll cut back to the beginning and tell the how-the-hell-did-that-happen story. I promise there will be no blood, crystal meth, or ATM homicides.

Imagine me, in an audio/video recording studio at the brand-spanking new Levi’s Stadium, home of the SF 49ers. I’m completely bald with a henna tattoo covering my entire head, wearing jeans, boots, and a pink mesh football jersey with a big 49 on the back, framed by the words “Early Screening, A Crucial Catch.” I first am planted on a stool, lights blaring and eclipsing all but the fuzzy outline of the camera lens. In the room are a cameraman (adorable) and a director (even more adorable) and another pink-mesh clad breast cancer spokesperson; she however, seemed both more excited (downright giddy) and more prepared than I.

A series of awkward, not-quite-right interview questions follows: “How did you feel the moment you were diagnosed? (Really? How do you think I felt?!?!); What has been most challenging for you? (Actually, I have been blown away by the beauty that keeps emerging in this journey, making even the nausea and exhaustion pale in comparison to the extraordinary experiences that continue to inspire and empower me, including the fact that I’m getting interviewed for a breast cancer film in Levi’s stadium…).

After the interview, I’m moved over to a set filled with 49ers gear – shoulder pads, gloves, footballs covered in pink ribbons, helmets. I’m then filmed interacting with the gear – catching a football (challenging, as it emerges from a black hole of darkness), “suiting up” in my pink jersey, and pushing the pink-ribbon side of the football into the camera slow motion style.

Huh??? Yup, bizarre. It all began hours earlier when I arrived at Levi’s Stadium for a breast cancer survivor spa crawl in the cheerleader’s Goldrush Lockerroom. 30 other breast cancer ladies and I were treated to facials, massages, hand treatments, make-up makeovers, and, yes, oddly, hair styles (turns out I was one of only two baldies there as most of the ladies beat their cancer years ago). As the event proceeded, I was approached by a staff member asking if I’d be willing to bring my bald, henna’ed head into the studio for an interview. The final clip (referred to as a public service announcement, hmmmm…..) would be shown on the jumbotron at the next Sunday’s game, just before 200 pink mesh dressed breast cancer survivors rush the field at half time to symbolize our fight against cancer.

Inside the Goldrush Lockerroom, where cheerleader magic happens.

Ian WIlliams dug the henna.

Now some of you are reading this in disbelief, so excited that I had access to the inner-sanctum of Levi’s Stadium, treated to spa delights, and held up as a hero by the NFL. Others are rolling their eyes and perhaps fuming at the absurd confluence of two highly touchy issues of today, the pink-washing controversy and the NFL’s recent plunge into alleged masogyny, child abuse, and general women-bashing behavior. And I will say I was and still am caught between these two places – one of gratitude for the support and gifts received, including a bouquet of beautiful pink flowers given to each pink lady by a local florist/fellow cancer survivor, mixed with cynicism at the corporate machine and its haughty claws that have sunk deeply into a profoundly troublesome disease to the benefit of their profit and public image. At the end of the day, however, the words of the event organizer resonate powerfully within me. She stood up as we all ate a post spa-crawl dinner at the stadium’s fine new Michael Mina restaurant. “I’ll admit that we are using you,” she said, “but there will be 68,500 people at this game on Sunday watching you all, and if even one woman is motivated to get a mammogram then you could be saving a life.” So, for now, I’ll wear my pink mesh and fall in line with my sister-survivors in hopes that awareness, even when enmeshed with things complex and political, will save lives and raise crucial research dollars so that women everywhere can beat this disease.

That's me on the jumbotron at this past Sunday's 49ers game... I didn't make it to the game due to the extreme chemo-unfriendly weather conditions...however, clip can be viewed here:

http://www.49ers.com/video/videos/49ers-Honor-Breast-Cancer-Survivors-with-Ceremony/9e5356b2-d83d-446e-b03f-69371b0363cc

1 note

·

View note

Text

Is the chemo bag half full or half empty?

Last week’s infusion marked half way to sixteen, which happens to be Andy’s and now Dylan’s favorite number. Andy has long been committed to sixteen, enamored by its tidiness, its quality of breaking down easily into even parts. When I break sixteen into two sets of eight chemo infusions, I’m left at the midpoint of a journey that at times is the peak of a mountain with views far, wide, and clear, and at other times like the bottom of a dark cavern where I strain to set my eyes on a waning light above.

It’s most often my physical state that determines my perspective on my chemo halftime show. On my good days, I’ve got energy, my nausea’s controlled, and I can run four miles with a good friend with a skip in my step. I might go out to lunch and actually feel hungry, order food without wondering how it will adversely effect my GI tract in one way or another. These half full days let me work, checking in intellectually with my beloved project, connecting with colleagues and being my professional self. I enjoy my children, and feel grateful for the simplicity that defines our days during this chapter – nothing else to consider but getting healthy. I feel like a cancer superhero, strong, energized, capable, and unwaveringly optimistic, soaring through town with a henna crown on my bald head. Halfway is an accomplishment, a trophy, a celebrated pit stop where friends cheer and offer mineral broth and fresh cut flowers. I feel grateful for the surprising experiences that have appeared along the way – being bald and beautiful; feeling invincibly able to win this battle; and, most stunningly, receiving love in measurements inconceivable from family, old and new friends, former students, and strangers on the street who greet my bald head with an initial alarm that almost immediately morphs into an open-hearted, essentially human offering of love and support.

However, there are moments when the side effects gather strength and momentum, colluding surreptitiously because there’s power in numbers. My nausea, an almost constant companion now, can peak and become a dizzying misery; my worsening neuropathy, a disturbing numbing, tingling, and pain in my hands and feet, can hurt and terrify me of possible permanent damage; my GI tract refuses to pause between stubbornly bound and boundlessly liquid, waking me at night to horrific pain and mess; and exhaustion and body ache that remind me of pregnancy and childhood flu keep me quietly in bed unable to self-entertain with books or screens.

In these moments, this journey feels truly endless. Halfway is a cruel torture sentence and I cannot fathom that I’m about to do what I just did all over again, but worse as the toxins cumulate and my platelet count wanes. I pause shoulder-slumped squinting forward unable to see the end, its view blocked by towering pill bottles. The road ahead narrows as it unfolds ahead of me, disappearing into an unwelcoming darkness.

These moments have been rare during my own halftime show, in fact I can count them on one slightly numb hand. And they pass, often with help from some pillar of strength – Andy or my mom, my closest lieutenants, or maybe a text from a friend or a gift in the mail -- and usually from more pills that ease the symptoms. But beyond the pills and support, I must access that core place inside myself, that inner reserve of strength and determination, like my own private stash of perspective serum, locked safely deep inside of me and accessible only with a password of even breath, conscious centering, and resilience. I push through and reorient, at peace again knowing my chemo bag is unquestionably half full, and that the road ahead, lit by love and spiritual growth, will end in just eight more infusions as we arrive in celebration at a perfect sixteen.

0 notes

Text

Beautiful Bald

For months now, I’ve been writing my I’m-now-bald blog entry in my head. It’s pretty much involved equal parts devastating feelings of loss, vain pangs of insecurity, and angry roils of resentment. I’ve spent a fair amount of time thinking about my impending hair loss. For a while, I planned to use a product called Penguin Cold Caps, head-shaped gel helmets that are frozen to -52 degrees F and strapped to my scalp every twenty minutes throughout each of my sixteen infusions, including one hour before and two hours after, making what is already a dawn to dusk day longer. I was told the caps might save 75% of my hair, or, on the unlucky end of the stick, just 25% of it. Ultimately and with wavering resolve, I made the call to go for bald.

In preparation, I cried my way through my first short haircut of my life, until my beloved hairdresser Nichole swiveled me away from the mirror. However, when she turned me back cut complete, I saw in the mirror a very different but beautiful version of myself. I loved it! And I spent the next several weeks as a woman with short hair -- sharper, stronger, more chic – and learned that the lack of maintenance alone made my new cut a winner.

As the Tuesdays come and go, and the chemo does its most essential work of shrinking my tumor and eradicating any cancer cells in my body, so does it attack the rapidly reproducing hair follicles on my head. For the last few weeks, I have awoken each morning to a pillowcase- and mouth-ful of hair, and my scalp has burned with a very unique and painful sensation. Day by day it thinned so I started wearing hats and scarves, or combing what hair remained over the thinnest parts. Two days ago, I woke up, looked in the mirror, and saw a large bald spot on top of my head.

I cried to my sister. “This might just be the worst part,” she said. I was terrified that my cancer journey which thus far has been on my own terms, would be taken public without respite, that I’d be some version of sick person that people stare at and pity. I was scared that I would look ugly and wrong and that this would make an already challenging time unbearable. I sunk as low as I’d been in weeks, but with the help of friends and family (and some retail therapy), pushed through to a place of acceptance.

Andy, Jasper, Dylan and I shaved my head today. I sat down on a little kitchen stool while they huddled around me. Somehow the moment had transformed to one of excitement and possibility rather than fear and sadness. Each kid took a turn with the clippers, and we all laughed and howled as the chunks of hair fell onto the wood planks of the kitchen floor. “What!?” I said, “Is it ok?”

“It’s amazing,” said Andy, “You look beautiful.”

Dylan pulled me to the biggest mirror in the house and I found my bald and beautiful reflection smiling back at me. I felt a surge of power and relief and thrill! Could it be that I might actually like being bald? Is it possible that I could look beautiful, feel light and lovely, and wear no hair like a badass cancer-fighting warrior? It’s seems that yes, I can, and although I’m sure there will be moments when I long desperately for my locks, I have no doubt that this too is an unmistakable gift.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Summer's Child

I remember saying to one friend shortly after my diagnosis, “Not only do I need to deal with my cancer, but I need to deal with my kids dealing with my cancer!” At first, the kids seemed to take it all in stride. We did have to clear up any confusion regarding the fatality of the disease, explaining that just because their beloved grandfather and, yes, it’s true, hamster both died from cancer this spring does not mean that their mother will follow the same path. We explained that we’d need to cancel out of the many summer plans we’d just finalized including trips to the east coast and to family camp in the Sierras. For the first time, they’d be staying put all summer and going to full time day camp, a prospect they initially found exciting.

Seven-year-old Dylan has kept a relatively stable perspective on the whole thing, and has pretty much bounced through the summer sporting a consistent sheen of suntan and boy-dirt. Nine-year-old Jasper, however, weeks into the summer began to show signs of an inner roiling tension, an instability like we’ve not yet seen in her, evidenced by angry outbursts inspired by seemingly insignificant moments in a pattern we at first struggled to decipher. We had ourselves a situation and it was rapidly escalating to terrifying proportions, behaviors that we imagined we’d be spared until the ominous teen years. Doors slammed hard, runaways were attempted, and heretofore unspoken words were slung across failed family dinners. And then came words, strung together in heart-piercing sentences like, “My life will never be normal again,” and, “You will be cured but I may never be.” Meanwhile, the nausea brewed in my belly, my scalp burned with rash and dying follicles, and fatigue kept me in bed more than out. Not a pretty scene in the Donner house.

Rather stunned by Jasper’s rage, Andy and I crafted a game plan that involved assuming, with measurable apprehension, that her behavior was directly related to my health, and that the best way to go was loving and supportive rather than punitive. We patiently sat through her tirades, totally insecure in approach but solid in resolve to help our daughter navigate this uncharted emotional hurricane.

With each episode has come a move towards Jasper’s self-understanding that her life has suddenly changed, that she no longer feels an essential sense of control and safety, and that this makes her angry over small things that aren’t what she wanted or expected. She is developing strategies to manage the anger and we can actually watch her gather control of herself and walk outside or take a deep breath. At times, the anger folds into utter sadness, her brown eyes filled with anguish and a life grip around our necks. At these moments, our hearts break for our little girl, and our own anger rushes in because we cannot protect her from this.

But isn’t it true that Jasper is developing skills that some adults never master? To self-reflect, to understand her pain, to recognize the root of her anger, and to develop the ability to manage it all? Might it be true that this journey is a gift to Jasper, that she will emerge more prepared for whatever life has to offer? I think so, and I am in awe of the wisdom, strength, and power that I see in her right now. While she suffers so, she is growing up and it is amazing to see. And, as she wonders if her life will ever be ordinary again, the answer might be that no, it will be extraordinary.

4 notes

·

View notes