Text

Merry Christmas your arse

Originally published on Facebook on this date in 2012.

**********

As many of you know, I do a radio show. Every year I dutifully pull out my shopping bag of Christmas music, which I keep segregated in a corner of a closet, and attempt to compile a few sets of Yuletide music for my listeners who may go for that sort of thing. But there's only one song I spin every year: "Fairytale of New York," from the Pogues' 1988 album "If I Should Fall From Grace With God."

It's always seemed, to me, a perfect Christmas song, though it begins in an NYPD drunk tank. It manages an extraordinary feat: It is sentimental and unsentimental at the same time, romantic without ignoring the contusions that romance scores on us all (in what other Christmas tune can you hear someone call their loved one "a bum, a maggot...a cheap lousy faggot?"), celebrating the holiday while acknowledging the disorder and gloom that sometimes settles on celebrants at this time of year. As a composition, its melodic beauty never fails to captivate me. The performance is full of zest (especially in the lilt of its tin whistle), and the orchestral swell at the end always creates a palpable feeling of being uplifted.

The song was a lovely vocal collaboration between the Pogues' bibulous lead singer Shane MacGowan and Kirsty MacColl, daughter of the English folk icon Ewan MacColl and a U.K. star in her own right. So realistic and effective is their give-and-take on the song that if you didn't know it, you'd never believe the pair of them were not actually involved in a relationship. MacColl's turn, which plays in sweet counterpoint to MacGowan's drunken catarrh, is especially splendid, a poised mixture of affection and bile. ("Happy Christmas your arse.")

The song is probably best known visually from its original black-and-white video, but this live performance from 1988, filmed before a vocal audience, is the most winning version I've seen:

youtube

This wonderful 2006 BBC documentary about the song also serves as a hip-pocket history of the Pogues and Kirsty MacColl, who was killed in a 2000 boating accident. It's very funny and revealing; it's in six parts, so follow the adjacent links:

[video now unavailable; thanks Warner Music Group.]

The original video is linked in this recent story about "Fairytale" in the Guardian by the fine British writer Dorian Lynskey:

I never get tired of "Fairytale of New York." It's a part of the fabric of this maddening holiday, which calls up so many conflicting emotions in me -- sadness, longing, remembrances of drunken Christmases past, a kind of spiritual craving, and even sometimes a sort of disjointed joy. My mother died two days after Christmas a few years back; I never had the chance to play this song for her, and don't know if she was aware of it, but I think she probably would have appreciated it.

In October six years ago, my younger son Zane sat in with his brother-in-law's band the Filthy Thieving Bastards at a gig by the reunited Pogues at the Fillmore in San Francisco. I flew up to attend the show, and Zane and I sat in the VIP section when the Pogues performed.

They played "Fairytale of New York," with the young daughter of Jem Finer, who co-wrote the song with MacGowan, taking MacColl's part. During the song's climax, as fake snow drifted down from the ceiling, MacGowan soddenly swept her into his arms and slowly danced with her like a drunken bear. It was one of the greatest things I've ever seen on a stage. I was on verge of tears.

[here's video of Shane and Ella Finer performing the song in 2012:]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PIh6-aD-Cc0

"Fairytale of New York" perfectly defines my Christmas every year. Perhaps it does yours as well. Merry Christmas to all (especially to my boys Max and Zane). May the wind be always at your back, and hopefully you won't spend tonight in the drunk tank.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Lou Reed (Variety, 10/27/13)

Lou Reed died on this date 10 years ago, and Variety asked me to write an appreciation, which I re-post here.

**********

From the remove of 47 years, it is difficult to adequately calibrate the impact of “The Velvet Underground and Nico,” the debut album by the New York band fronted by Lou Reed, who died Sunday at 71. Bearing a cover by Andy Warhol that could literally denude itself (“peel slowly and see,” the legend read), the LP was a shock to popular music’s system. It addressed topics – heroin addiction, sexual aberration – that had hitherto been taboo in popular music, and mounted Reed’s literally stunning lyrics in a matrix of molecule-rearranging noise. It is one of those few records of which this can be said: Nothing like it had ever been heard before, and it permanently altered notions of what was possible, and permissible, in rock music.

While Reed was capable of shaking the foundations of propriety with compositions like “Heroin,” ‘I’m Waiting For the Man” and “Venus in Furs,” and would push the boundaries even further with subsequent outbursts like “White Light/White Heat,” “I Heard Her Call My Name” and the orgiastic “Sister Ray,” he proved he was no one-trick pony. He was capable of penning the most tender and empathetic ballads in the rock canon – “I’ll Be Your Mirror,” “Pale Blue Eyes,” “I’m Set Free,” the astonishing “Jesus.” He also proved that he was a rock classicist at heart with such much-covered standards as “Sweet Jane” and “Rock and Roll,” the latter of which may be the definitive statement of the joy that lies at the heart of the music.

After Reed exited the Velvet Underground after years of infighting and discord in 1970, he embarked on a solo career that was characterized over its course by periods of extreme risk, infuriating sloth and intermittent brilliance. He wrested glam from the British with “Transformer”; took his own stab at rock opera with the lush, depressive “Berlin”; ground ears to pulp with his two-LP noise extravaganza “Metal Machine Music.” Using more conventional elements of rock music but seasoning them with his hectoring style, he forged such highly personal latter-day works as “Street Hassle,” “The Bells,” “The Blue Mask,” “New York” and “Magic and Loss.”

Because he was a thorny, restless and often reckless spirit who proceeded to the tattoo of his own drum, his work could succumb to abject failure: Witness his Edgar Allan Poe homage “The Raven,” his misbegotten collection of guitar pieces “Hudson River Wind Meditations” and his last release, 2011’s “Lulu,” a much-maligned collaboration with Metallica.

But such failures were ultimately understandable and could even be anticipated, since from the start of his career Reed’s rep, and ultimately his import, rested on his willingness to take chances. That was never a sure way to conquer the charts, but it was a route to change, and Lou Reed permanently altered the musical landscape. Seemingly answerable to no one and nothing other than himself and his own artistic impulses, he became, to his discomfort, an exemplary figure. His influence has long been a given; especially in the punk and post-punk era, dozens of bands embraced his sound and style. Watching early sets by such groups as L.A.’s Dream Syndicate was like watching young, half-formed performers groping towards their own essence, with Reed’s work as a road map.

As a personality, he could be prickly, harsh, forbidding; his confrontations with music journalists held the status of legend. The caricature is maintained in “CBGB,” the recent film about the New York punk club, in which a character called “Lou Reed” makes a cameo appearance, with fangs out. Reed played himself best. In Allan Arkush’s 1983 rock movie “Get Crazy,” he portrayed a rock star named Auden. It is not a great picture, but he elevated it with his presence. He gets the last word in the film, under the credits, singing, in his wobbling, drawling voice, a song called “Little Sister” – a heart-on-the-sleeve number with a corking, lyrical solo at its end.

It’s surprising, sweet, loving. But then, he was an artist of many dimensions, and surprise was so much of what Lou Reed was all about.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

DEVO, Los Angeles Reader, Oct. 20, 1978

Take it from a fairly recent refugee, there are some basic problems with the American Midwest. “Morning Devotions” heralds the TV sign-offs around 1:30 a.m.

You have to drive 10 miles in the middle of the night to pick up a six-pack at the nearest Stop-n-Go. The jukeboxes in the local saloons feature Carly Simon, Dan Hill and college fight songs. The women have thighs like telephone poles, butts like half-empty potato sacks and think that down jackets and air-force parkas are high fashion. Mostly, the Midwest just stinks. Literally. The air is perfumed by the belched exhalations of a million factories stoking the Dispoz-a-Culture. In Chicago, you strangle on bitter lungfuls of “ozone alert” air. In Gary, the sky shines orange with the filings of the local steel mills. And in Akron, you can smell the essence of the Rubber City’s tire factories standing in the atmosphere like a hundred wheelies.

Post industrial depression in the Midwest breed a certain kind of teenager and a certain kind of rock ‘n’ roll. Midwestern kids escape into rock with a sort of fervent desperation bred by the mind-dulling landscape. A Midwestern rock show is a combination concert, party and fire-fight. Anyone who has ever witnessed a show at Chicago’s Aragon, Cleveland’s Agora or Detroit’s Cobo Hall knows what I mean. It’s not surprising that Vietnam writer Michael Herr, in a recent issue of Crawdaddy magazine, used nothing but combat metaphors to describe a Ted Nugent show in Detroit.

Aggressive rockers demand aggressive music, and Midwestern rock has an impressive history. Midwestern punk-pop of the early and mid-sixties bred such bands as the Cryan’ Shames, the Buckinghams and the imoortal Shadows of Knight (of “Gloria” fame), who barnstormed their way through teen rock clubs with funny names like the Sugar Shack and the Wild Goose. In the late sixties, which had already spawned the classic soul music of the decade, gave birth to the heavy metal Motor City Madness of such groups as the MC5 and the Stooges. The impact of Midwestern rock is being felt in the commercial rock of the late seventies. Such current hot sellers as Bob Seger, Ted Nugent and REO Speedwagon have all been around for 10 years, hauling ass and equipment from Cedar Rapids to Urbana to East Lansing, playing 200-plugs gigs a year, thrilling hordes of drunk, luded-out kids with a uniquely plains-derived brand of no-nonsense thunderrock.

Although balls-out rock still reigns supreme in the heartlands, there is growing evidence that the seventies are breeding a potent new strain of mutant rock. Strange noises have begun to emanate from, of all place, Ohio, where an insular group of young intellectuals anr cok ‘n’ rollers are making music that could change the face of popular music in the eighties. The industrial centers of Cleveland and (more important) Akron have brought forth a small nucleus of crazed rockers influenced by such diverse sources as Captain Beefheart, musique concrete, and the Stooges.

Two bands stand out in Cleveland: the frantic, nihilistic agressorockers the Dead Boys, who seem intent on one-upping the death-enamored shenanigans of Iggy and the Stooges; and Pere Ubu, perhaps the most intense and radical band in America today, who combine gnarled vocals, synthesized blips and roars, and twisted saxophones into a frightening vision of the void. Pere Ubu’s first album The Modern Dance (Blank Records 001) and Datapanik in the Year Zero (Radar English import RDR 1) are unreservedly recommended to those with a taste for music played on the outside. The Dead Boys’ two records are uneven, but may be appreciated by lovers of the loud and stooped in rock ‘n’ roll.

But Akron is where the action is, it appears. Stiff Records recent sampler The Akron Compilation (Stiff import Get 3) demonstrates the energy and diversity present in the Rubber City. Influences range from Brenda Lee to Jeff Beck to Frank Zappa. We should thank Stiff for putting together these homegrown singles for posterity; if it weren’t for The Akron Compilation, interesting limited editions by such unusual talents as Jane Aire and the Belvederes, Rachel Sweet, Tin Huey, the Bizarros and the Rubber City Rebels would vanish without a bubble on the surface. That would be a pity, because the album is full of unusual songs, enticing hooks, contorted rhythms and odd vocals that advertise the true flowering of Middle American strangeness.

Oddly enough, the most esoteric, forbidding and demonic of all Akron bands is the same band that has attracted the most attention and garnered the greatest popularity. This is, of course, the De-evolution Band, better known as DEVO.

DEVO excited the cognoscenti last spring with their astounding first single “Jocko Homo” b/w “Mongoloid.” The single, home-made on the band’s own Boojie Boy label, laid out their entire concept, a kind of flip side of Darwin that dictates the reverse evolution of mankind back to apedom. “God mad man, but a monkey supplied the glue,” DEVO sang, implying that the glue is rapidly becoming the essence. In this world, DEVO said, a mongoloid can wear a suit, hold down a job, and nobody will give a good goddamn.

DEVO’s rather rarified ideology could have been boring, were it not powered by a rock ‘n’ roll rhythm full of exhilaration and humor. The descending chords and synthesized blurps of “Jocko Homo” offered up a band that, while they seemed deadly serious about their message, imbued it with a sense of warped humor.

The group’s second self-recorded release, “Satisfaction,” may prove to be a major recording of the seventies. In the Rolling Stones’ original version of that rock classic, Mick Jagger’s tough, pitiless voice belied his sung “I can’t get no satisfaction.” We all knew he was getting all the satisfaction he could handle; it was the audience of the song that identified with the message.

In DEVO’s “Satisfaction,” the disjointed rhythmic pulse and Mark Mothersbaugh’s quirky vocals turn Jagger’s hymn of self-reliance into a psalm of modern defeat. The group turns an archetype of macho-rock posing into a real expression of tension and impotence, leavened, as always, with a parodic twist. DEVO has remained silent for practically a year, straitjacketed by some confused record company dealings. The group finally burst out into the open recently, with television appearances, the release of their first album (Q: Are We Not Men? A: We Are DEVO!, Warner Bros. BSK 3239), and two evenings of shows at Hollywood’s Starwood last week.

Are We Not Men is a quintessential piece of seventies rock, full of angst, self-doubt, terror and distaste. It isn’t perfect: The production (by technocrat Brian Eno) is a little too thin at times, and one song, “Shrivel Up,” fails because of its simple-minded lyric and stiff musical construction, but it is an auspicious debut that gives a perfect delineation of the DEVO world. Like many of the new breed of Midwestern bands, DEVO are post-industrial reactionaries. They sing about the inadequacy of the much-vaunted orgasm (“I think I missed the whole-a-hole-a-hole,” they croon in “Sloppy”), the futility of religion (“OK, relax, and assume the position,” Mark Mothersbaugh screeches in “Praying Hands”), the inexorability of death (their “Come Back Jonee” is a play on the teenage death song syndrome of the fifties and sixties), and the replacement of romance with sexual frustration and aberration (the topic of “Uncontrollable Urge” and “Gut Feeling”).

Grim stuff, you might say, but DEVO animates their themes with Mark Mothersbaugh’s hilarious vocals and shrieks, cartoony capering rhythms and jittery, humorous playing. DEVO’s ape’s-eye view of manking comes a cross on record, but it is in concert that the forcefulness and originality of their concept may be fully perceived. Visually, DEVO are the complete embodiment of their themes. As they point out in their official bio, the band members are “almost uniform in height and weight.” The front line is made up of two sets of brothers – Jerry and Bob Casale and Mark and Bob Mothersbaugh.

When these five apparent clones make their first appearance, dressed in identical suits made of prophylactic rubber and cardboard industrial shades, one immediately makes the connection between the players and their obsessions with evolution, natural selection, recombinant DNA, brain-eating apes and other conceits dealing with sciences manipulation of our genes. DEVO plays the role of what they call the “Smart Patrol” – “suburban robots who monitor reality” – and their impersonation, complete with cybernetic movements, uniforms, and assembly line-derived time signatures, make for a show that is at once terrifying, deeply ironic, funny and plenty of fun.

DEVO is an important band because it is the first to deal with modern industrial and scientific society and its discontents on such an explicit and intellectual evel. Indeed, the band’s conception may be so smart that they risk leaving a good deal of their audience behind. It is already readily apparent that a large part of the DEVO audience appreciates the group merely for their novel musical and theatrical approach. I started doubting that the crowd was getting the picture when a large part of the Starwood audience began very earnestly aping Mark Mothersbaugh’s fascist salutes during “Praying Hands.”

DEVO divides their world up into “aliens” those who have an understanding of their “otherness” – and “spuds” – the vast majority of the dull, brain-damaged and ordinary. It was clear at the Starwood last week that there was a hefty number of spuds in the audience who were digging DEVO on the same level that they might enjoy such novelty acts of the past as the Hello People or the Crazy World of Arthur Brown.

DEVO is a band that is making the transition from a cult item to the property of a mass audience. Its current set is more conservative than the shows that brought them attention last year. Although they still perform unrecorded songs such as “Mr. DNA,” “Smart Patrol” and “Wiggly World,” they seem content to stick to album material; they perform all but two songs from Are We Not Men? Their symbol of infantilism, Booji Boy, without a doubt the most powerful and suggestive figure in the DEVO universe, failed to put in an appearance at last Tuesday’s show. It sobered me to find one of America’s most revolutionary bands already acquiescing to the demands of the music industry.

These reservations notwithstanding, DEVO appears to be ready to be the first of the Midwestern New Wave to break out nationally. Whether rock audiences will respond to the sheer novelty of the DEVO look and sound or to the band’s truly perverse socio-scientific ideas, only time will tell. For now, the only thing to say about DEVO’s coming-out is that their Janitor-in-a-Drum brand of industrial-strength post-nuclear rock ‘n’ roll is the most welcome new musical genus of the year.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Poets of the Fess Hotel

Today, through a chain of associations called up by a book about alcoholic writers, and then by a volume of John Berryman’s best known work, I found myself ratcheted back to the year 1971, when I briefly entertained the delusion that I could write poetry. I was actively encouraged in this futile pursuit by a friend named John Tuschen, who cited Berryman as his favorite poet.

In ’71 I was living in Madison, Wisconsin, and had recently dropped out of the university there, after experiencing a drug-induced breakdown in late 1970 that led to several weeks in a psychiatric ward at the campus hospital.

After a brief period spent licking my wounds at my mother’s apartment outside Chicago, I returned to “Madtown,” where I immediately returned, unburdened by school work, to doing what I had been doing: drinking and using drugs, enthusiastically. The psychiatric care recommended by the hospital did not seem like a particularly useful option, and potentially an endless one, so I dropped my shrink after three sessions.

My style of therapy took place in the warm confines of the 602 Club, the campus-adjacent bar on University Avenue that I had begun to frequent before my lockdown adventure. This saloon had become a main hangout for the local bohemians in training. I’d started going there when I was working in the acting company of Broom Street Theater, the local experimental stage. In the theater’s early days, John Tuschen had started up “The Camel, The Lion, and The Child,” its in-house literary magazine. We had gotten to be friends, and we both like to drink, so I’d roll down to the bar after a day’s work as a stock boy in the small corner market one block up the street. (My apartment, which I briefly continued to share with two college friends, was also nearby; we served as custodians in the building, and the rent was cheap.)

Tuschen looked like your average hippie, with a skinny frame and long, straight, lank hair. He looked at the world sharply through a pair of rheumy, often red eyes. He had the vestiges of a childhood speech impediment, and the slight hitch of a stutter gave his poetry readings a unique rhythm. We’d sit together in the 602 night after night, kibitzing, arguing, and people-watching in the narrow, overheated room over the joint’s trademark drinks, big cold glass schooners of beer, which washed down cheap bottom-shelf shots. Alcohol was our bond.

Invariably Tuschen would pull some new thing he’d written out of his pocket. He was a poet in the big Ginsberg style, and in the days we were closest he was hammering away at a long “Howl”-like jeremiad about America called “Your Muther’s Eye.” We would often be joined by another aspiring poet who called himself Hannibal Plath, a sweet, angelic-looking guy who broke the heart of just about every woman who crossed his path, and sometimes by my new flame Connie, a statuesque redhead from St. Petersburg, Florida, who had me utterly in her thrall.

These were heady times, and you wound up getting swept away by them. I went back to working sporadically at Broom Street, which was charitably housed in St. Francis House, the youth Episcopal center a few blocks up the street from the 602. The theater began to mount irregular “Bacchanals” — free-form evenings of theatrical vignettes, poetry readings, music, and what-have-you. (Into the latter category fell a premiere slideshow screening of Michael Lesy’s remarkable photo-essay “Wisconsin Death Trip,” later a famous book drawn from newspaper clippings and hellish photos shot in the late 19th century in upstate Black River Falls, which unspooled at the theater over a long, dark John Fahey guitar piece.) Tuschen and some of the other Mad City poets were invariable fixtures of the events. My theater mentor, director Joel Gersmann, also read; he had written his own volume of what he called “junk poetry,” titled “Deep Shit.”

It was an anything-goes time, and, inspired by the company I was keeping, I started writing some poetry of my own. My stuff was never burdened by the larger demands of the form — it was free verse, unambitious self-expression, post-adolescent soul searching and bouquet-tossing love songs for my muse Connie (who was essentially my principal audience, if truth be told). My sense of rhythm was fair enough to keep the work aloft. Though it was little better than doggerel, Tuschen agreed to throw down the few bucks it cost to type up, lay out, and photocopy a couple hundred copies of a small book of my work, which I titled “Red Boots” (after my girlfriend’s favorite footwear) under his Quest Publishing rubric.

By mid-1971, I was chafing at my then-current living situation in a hippie pad off campus, where I witnessed the dramatic meltdown of one of my three roommates, a young, drug-crazed heiress we called “Spacey Gracie,” whose family had the police swoop in and drag her off to a private loony bin. Tuschen proposed that I move into an open room down the hall from his at the Fess Hotel.

Located at 123 E. Doty St., a block and a half away from the state capitol that served as the city’s hub, the Fess was something of a local landmark. A residential hotel that had opened in 1854, it had been operated by the Fess family for four generations; 69-year-old Alice Fess, the wife of the current owner, was the building’s truculent manager.

The place was then on the downward slope of its existence; at that point downtown Madison had gotten a little seedy, and it was surrounded by a number of bars and strip joints that catered to the state office workers and political lobbyists. Ironically, considering the amount of drinking that went on around and in the hotel in those days, one of the most famous Fess patrons in earlier times was the axe-wielding temperance crusader Carrie Nation. (Abraham Lincoln was said to have stayed there, but no one was ever able to confirm that for sure.) The place had a lobby where most hours you could find one of the older tenants dozing in a soiled chair or zoned out in front of an ancient TV set. Both the day desk clerk and the night clerk were walleyed, so communicating with the staff, who always seemed to be staring at something to your left, was a disconcerting experience.

I don’t think I paid more than $150 a month for a second-floor single at the Fess. Accommodations were unspectacular: The room contained an uncomfortable bed, a stained sink, a small closet, and a tiny, scarred desk in front of a window that looked out onto the grey street, where I tapped out my work on a turquoise Olivetti portable. I used the communal bathroom just outside my door, which was occupied competitively by the other tenants. Tuschen had a suite down the hall — he was the Fess pathfinder, after all — and Hannibal also had a room on my floor. For obvious reasons, Tuschen’s spacious room became the focal point for a considerable amount of drinking among the three resident versifiers, all of us living out our Beat Generation fantasies.

A couple of times, the university’s visiting professor of creative writing entered into this fantastical den, and he made his presence forcefully known. His name was George Barker. Though he is little known or remembered in America today, Barker was one of England’s great poetry prodigies of the 1930s. He was T.S. Eliot’s protégé, and William Butler Yeats was an admirer.

At 58, he was gaunt and lined; he was suitably dressed in tweeds, and displayed the waspish, razor-tongued manner of the old-school British intelligentsia. He was accompanied by a smart, auburn-haired, very beautiful young woman he introduced as his wife. But we did not know that Elspeth Langlands was not yet George Barker’s wife — his spouse Jessica, a Roman Catholic, refused to grant him a divorce. Elspeth had been introduced to Barker, who was 27 years her senior, when she was 22 by Barker’s longtime mistress Elizabeth Smart, who had tired of the poet’s violent, alcohol-fueled behavior (which she, an alcoholic and drug addict herself, had chronicled in a 1945 novel in verse, “By Grand Central Station I Sat Down and Wept”) and happily handed him off to a new partner.

Barker would huddle with Elspeth on the floor of Tuschen’s flat with a gallon glass jug of Annie Green Springs, the sickeningly sweet, cheap party wine, at his side. He would get hammered on the foul stuff, which was manufactured purely for effect, all night long, as he diced up the manuscripts that Tuschen and Hannibal would read aloud for him. The work of these young writers could not have been further from the well-manicured “New Apocalyptic” writing that had won him kudos three decades ago, and he had little patience with it.

I never had the temerity, or the courage, to try out my jejune material on him, but one evening I made the mistake of reading Frank O’Hara’s “The Day Lady Died,” the New York poet’s shocked, moving reaction to Billie Holiday’s tragic demise.

After I finished, he paused for a beat and said, “Dear boy, that’s pure shit.”

That cold dismissal of a writer I love essentially ended my poetic aspirations for good.

“Red Boots” was published in early 1972, and sold tepidly at the Madison Book Co-op, the hip book outlet that became Bukowski’s local sponsor. While I was already re-enrolled at the University of Wisconsin, I managed to get a chance to live out a couple of my poetry fantasies before I hung up my spurs for good. The school actually hired me to give a reading on campus; I was paired with Bob Watt, the snaggle-toothed, lecherous pest exterminator/folk artist/“art” photographer who was a local legend in Milwaukee. Incredibly, Tuschen also convinced the university library to purchase copies of the entire Quest catalog, and so today “Red Boots” resides in the UW’s rare books collection. (I do not anticipate any scholarly interest — it’s truly dreadful.) After my father died in 2002, I learned with amazement that he kept a copy of the book — which contained a poem about our strained relationship — in his office desk.

Mrs. Fess learned from her clerks that Connie had been stretching herself across my narrow hotel bed, so I was politely asked to vacate the premises of her none too clean but nonetheless respectable establishment, and I moved into my girl’s pad on Fraternity Row. The Fess, which became a popular downtown restaurant for 20 years after the family sold it in 1975, is still operating today as a gastropub. The building was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1978.

We all went our separate ways. John Tuschen, who had titled one of his book “The Percodan Papers” after a favorite intoxicant, quit drugs and alcohol and became a drug rehabilitation counselor. In 1977, he was named the first poet laureate of Madison. He died in 2005; his longtime companion Suni asked me if she could reprint an honest but unflattering poem about him for a memorial volume, and of course I said yes, despite my misgivings about its quality. Hannibal left town, became a minister, and wrote a couple of spiritually themed self-help books. George Barker died at 78 in 1991, two years after he finally married Elspeth following the death of his wife. Elspeth Barker died at 81 in April of this year. A respected journalist, essayist, and novelist, she bore four of Barker’s 15 children.

Connie and I split up, then regrouped in Chicago, where we took root in a new bar on Lincoln Avenue. I began a protracted sidelong course to becoming a working journalist. I would learn that it was easier for me to write about what was in front of my eyes and ears than it was to chart the course of my heart. That great gift belongs to others.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Betty Davis Was a Big Freak

Written for the late lamented Music Aficionado in 2016, and republished on the day of Ms. Davis’ death, 2/9/22.

**********

To this day, the name Betty Davis – Betty with a “y,” that is – remains best known to connoisseurs of Miles Davis minutiae and ‘70s funk obsessives. While it’s true that Betty played an important off-stage role in the career of the jazz trumpeter, to whom she was married for just a year, and she undoubtedly made some of the best hardcore funk records of her era, she deserves to be recognized beyond the relatively narrow provinces of the jazzbo and the crate-digger.

Uncompromising, intelligent, brazen, aggressive, and not incidentally gorgeous, sexually provocative, and a fashion plate always ahead of the curve, Betty was a prophetic figure. Spawned by the explosion of music, fashion, and alternative culture of the late ‘60s, and by concurrent leaps in black consciousness and feminism, she was a take-no-prisoners singer and writer who presented herself as something new, rich, and strange with her self-titled debut album in 1973.

There were some badass contemporaries working the soul and funk trenches– gutter-tongued diva Millie Jackson and one-time James Brown paramour Yvonne Fair leap to mind immediately – but they seemed to be adapting tropes previously worked by male singers in the genres. Betty still sounds like something new: a tough, smart, demanding woman who reveled in pleasure and insisted on satisfaction, unafraid to claim what she wanted.

Despite the fact that she was associated with some high-profile male musician friends and lovers – beyond Davis, the roll call included Hugh Masekela, Jimi Hendrix, Sly Stone, Mike Carabello, Eric Clapton, and Robert Palmer – she was no groupie or bed-hopping climber. Possessed of her own self-defining vision, she was producing her own records and leading a tight, flexible little band by the end of her brief run.

In 1976, after completing four splendid albums (only three of which were released at the time), she disappeared, not only from the music business but from the public eye entirely. What happened? It’s an old story that many women in the industry will recognize: Her record company didn’t know what to do with her, and wanted her to tone down her act. Betty Davis wasn’t having any of that, thank you, and she hit the damn road.

She was born Betty Mabry in Durham, NC, in 1945. She grew up country, and was exposed to down-home, get-down music early. On the title track of her second album, They Say I’m Different, she runs down the artists who served as inspirations: Big Mama Thornton, John Lee Hooker, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Howlin’ Wolf, Albert King, Chuck Berry. The blues, in one form or another, is the backbone of her style.

Her family relocated to Pittsburgh when she was young, but at 16 she left home for the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York. There she was hurtled into the roiling cultural vortex of the Village. She took up modeling, working for the toney Wilhelmina agency, and began running with a posse of similarly disposed, equally beautiful women who called themselves the “Electric Ladies.” Sound familiar? One of her closest cohorts was Devon Wilson, for many years a notorious consort of Jimi Hendrix known for her freewheeling, outré sex- and drug-saturated lifestyle.

Mabry began to try her hand at singing, and cut a few self-penned singles. They were in an old-school mold in terms of structure, but her very first 45 hints at things to come. “Get Ready For Betty,” a 1964 track released by Don Costa (discoverer of Paul Anka and Trini Lopez and a key arranger for Frank Sinatra), is stodgy early-‘60s NYC R&B to its core, but its message is pointed: “Get out my way, girl, ‘cause I’m comin’ to take your man.”

She also made a stolid romantic duet ballad with singer Roy Arlington and, produced by cult soul man Lou Courtney, a homage to the Cellar, the New York club where she DJed. But she didn’t start reaching the upper echelon of the music biz until one of her songs, a hymn to Harlem called “Uptown,” was cut by the Chambers Brothers for their smash 1968 album The Time Has Come, which also included the psychedelic soul workout “Time Has Come Today.”

The Chambers association probably secured a singles deal for her at Columbia Records, and her first session for the major label was produced by her former live-in boyfriend, South African trumpeter Masekela, in October 1968. By that time, she had split with him: A month earlier, she had married a far more famous horn player, Miles Davis, whom she had met in 1967. Davis and his regular producer Teo Macero would head her second session for Columbia in May 1969.

Those two dates were released for the first time as The Columbia Years 1968-1969 earlier this month by Light in the Attic, the independent label that has restored Betty’s entire catalog to print over the last decade. While devoted fans can be grateful that the work is finally seeing the light of day, it does not make for easy listening, for it was clearly made by people groping in the dark.

Betty’s artistic persona was at that point completely unformed, and so her male Svengalis did their best to mold the clay in their hands, with feeble results. Masekela evidently completed just three tracks, two of which, “It’s My Life” and “Live, Love, Learn,” were issued as a flop single. The homiletic song titles give the game away; the music, straight-up commercial soul backed by a large group (which included Wilton Felder and Wayne Henderson of the Jazz Crusaders and Masekela), has nothing original to say.

The date with Miles is a bigger waste, if a more spectacular one. The personnel couldn’t have been more glittering: Hendrix sidemen Billy Cox and Mitch Mitchell; ex-Detroit Wheels guitarist Jim McCarty; bassist Harvey Brooks, studio familiar of Bob Dylan and former member of the Electric Flag; and Davis’ then-current or future band mates Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter, John McLaughlin, and Larry Young.

But nothing jells. The material is either weak (Betty’s directionless original “Hangin’ Out” is the best of a bad lot) or incongruous (lumbering covers of Cream’s “Politician” and Creedence’s “Born On the Bayou”). Worse, the jazzers are unable to lay down anything resembling a solid soul-rock foundation, and even reliable timekeeper Mitchell blows the groove on more than one occasion. Miles gets impatient with his spouse at one point, rasping over the talk-back, “Sing it just like that, with the gum in your mouth and all, bitch.”

Apparently intended as demos, the failed tracks were consigned to the tape library. By late ’69, Miles and Betty’s marriage was history. She left her mark on his music: She appeared on the cover of his cover of his 1968 album Filles de Kilimanjaro and inspired its extended track “Mademoiselle Mabry” (based on the chords that opens Hendrix’s “The Wind Cries Mary”) and “Back Seat Betty” from his 1981 comeback album The Man With the Horn.

Moreover, she moved him toward the flash style that would dominate his music through the mid-‘70s, by exposing him to the slamming music of Hendrix and Sly and exchanging his continental suits for psychedelic pimp togs. Would we know Bitches Brew, On the Corner, and Agharta without Betty Davis? Maybe, maybe not.

For her part, Betty remained in the wings for a while. She collaborated on demos for the Commodores; in London, she modeled, worked on songs for Marc Bolan of T. Rex, and declined a production offer from her then-paramour Clapton. Drifting back to New York, she met Santana percussionist Carabello. They became involved romantically, and in 1972 she relocated to the San Francisco Bay area, where Carabello’s local connections led to the formation of a stellar band to back her on a debut album.

One reads the credits for Betty Davis in awe. The rhythm section was the Family Stone’s dissident, puissant rhythm section, bassist Larry Graham and drummer Greg Errico (who also produced). Original Santana guitarist Neal Schon, future Mandrill axe man Doug Rodrigues, founding Graham Central Station organist Hershall Kennedy, and keyboardist and ace Jerry Garcia collaborator Merl Saunders filled out the instrumentation. The Pointer Sisters, Sylvester, and Kathi McDonald were among a large platoon of backup vocalists.

Issued in 1973 by Just Sunshine Records, an independent label owned by Woodstock Festival promoter Michael Lang (who also released a set by another unique woman, folk singer-guitarist Karen Dalton), Betty Davis was one hell of a coming-out party. Since her abortive Columbia dates, she had developed a unique vocal attack that could leap from a velvety croon to a Tina Turner-like shriek in a nanosecond. The stomping funk of the studio band backed her up to the hilt.

Like Turner, she was one Bold Soul Sister. The lust-filled opening invitation “If I’m in Luck I Might Get Picked Up” announces that a new game was afoot. The statement of romantic/sexual independence “Anti Love Song,” the lovers’ chess match “Your Man My Man,” and the self-explanatory “Game is My Middle Name” offer up a startling, hard-edged new model of a hard-funking female vocalist.

The album’s most affecting track may be “Steppin in Her I. Miller Shoes,” Davis’ level-headed elegy for her sybaritic friend Devon Wilson, who sailed out a window at the Chelsea Hotel in 1971. “She coulda been anything that she wanted…Instead she chose to be nothing,” Davis sings, implying that route wouldn’t be one she would take herself.

“If I’m in Luck” grazed the lower reaches of the R&B singles chart and the album failed to reach the LP rolls at all, but Davis was undaunted. For 1974’s They Say I’m Different, she took the producer’s reins, which she would hold for the rest of her career. While the backup lineup is less glitzy (though Saunders, Pete Escovedo, and Buddy Miles, on guitar no less, appear), the support is still sizzling; crackling drums and burbling clavinet put over a set of songs that may have been even stronger than those heard on her debut.

No one who hears “He Was a Big Freak” is likely to ever forget it; it’s a startling dissection of a masochistic relationship -- inspired by Jimi Hendrix, and not, as many have assumed, by Miles Davis (“Everyone knows that Miles is a sadist,” Betty remarked later). Almost as notable are “Don’t Call Her No Tramp,” a prescient condemnation of what we now call slut-shaming, and the autobiographical title track, with slicing slide guitar work by Cordell Dudley.

Different and its attendant singles tanked, but Betty managed to maintain her profile with live gigs noteworthy for their uninhibited bawdiness, on-stage abandon, and the star’s Egyptian-princess-from-outer-space wardrobe sense. By early 1974 she had assembled a hot, lean road band that included her cousins Nickey Neal and Larry Johnson on drums and bass, respectively, plus keyboardist Fred Mills and guitarist Carlos Morales. This lineup would back her on her last two albums.

The end of Just Sunshine’s distribution deal liberated Davis, who, at the suggestion of then-boyfriend Robert Palmer, inked with Palmer’s label Island Records. The company released Nasty Gal in 1975, and it may be Davis’ best-executed work. The pared-down backing lets the songs shine, and there are good ones here: The shameless title song, the vituperative blast at the critics “Dedicated to the Press,” and the out-front ultimatum for sexual satisfaction “Feelins” get right up in the listener’s face. The most surprising track is the ballad “You and I,” an unexpected songwriting reunion with Miles, orchestrated by the trumpeter’s famed arranger Gil Evans.

It’s a tremendous album, and Betty supported it with live shows that ate the funk competition alive. A bootleg of an especially out-there set recorded at a festival on the French Riviera in 1976 literally climaxes with Nasty Gal’s “The Lone Ranger,” an in-the-saddle heavy breather that Davis wraps up by feigning a loud orgasm.

One should remember that at this particular juncture, Madonna was studying dance at the University of Michigan.

But Nasty Gal faded with hardly a trace, and Davis’ relationship with Island swiftly became fractious. It’s easy to see why the label declined to issue her final album, originally called Crashin’ From Passion and ultimately released, after years as a bootleg, by Light in the Attic in 2009 as Is It Love or Desire. The collection, which leans heavily on songs about sex, doping, and heavy drinking, includes “Stars Starve, You Know,” an outright condemnation of the games record companies play:

They said if I wanted to make some money

I’d have to change my style

Put a paper bag over my face

Sing soft and wear tight fitting gowns

They don’t like the way I’m lookin’

So it’s hard for my agent to get me bookin’s

Unless I cover up my legs and drop my pen

And commit one of those commercial sins…

Oh hey hey Island

And that was all she wrote. Until writers began to seek her out in the new millennium as her records became available again, Betty Davis was an invisible woman, one who had blazed a trail that other talents, such as Prince and Madonna, would blaze more profitably after her. She was definitively ahead of her time.

Asked by one writer what she had done since leaving music, Davis, who turns 71 on July 26, responded with the most tragic thing one can imagine any artist saying: “Nothing really.”

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

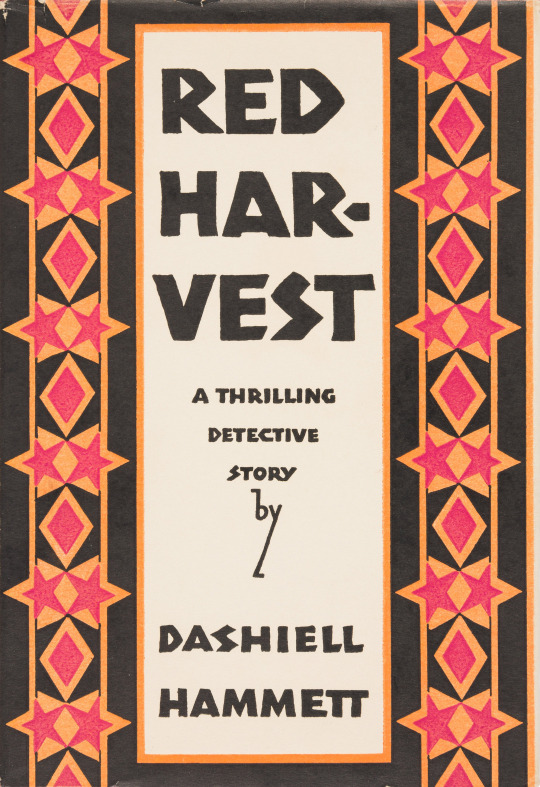

The movie legacy of “Red Harvest”

Strange but true: Dashiell Hammett’s fantastic 1929 hardboiled novel Red Harvest has spawned no less than four movie adaptations – including two certified genre classics – but has never been credited on the screen as the original source material.

The book was the debut full-length work by Hammett, who would go on to create such enduring screen characters as detectives Sam Spade (in The Maltese Falcon) and Nick and Nora Charles (in The Thin Man). However, screenwriting sleight-of-hand robbed the writer of full credit for his blood-soaked work, which spawned the samurai opus Yojimbo (1961), the spaghetti Western A Fistful of Dollars (1964) and the gangster sagas Miller’s Crossing (1990) and Last Man Standing (1996).

Originally serialized in the tough-guy pulp magazine Black Mask, Red Harvest featured a protagonist/narrator already familiar to readers of Hammett’s short stories: the short, fat, hard-drinking, and clever operative of the Continental Detective Agency known only as the Continental Op. (Hammett never gave him a name.

The book was inspired by Hammett’s own early career at the Pinkerton Detective Agency, which was frequently hired by industrialists to break strikes, employing any means necessary. The writer’s biographer Diane Johnson suggests that he may have been involved in the 1917 murder of a union organizer named Frank Little in Butte, Montana.

In the novel, the lone wolf detective arrives in a corrupt, lawless Montana town named Personville (known as “Poisonville” by some) at the behest of a local mining magnate and newspaper publisher, whose empire is being threatened by the warring gangs of mobsters he hired to bust up a labor conflict and have now taken over the city’s rackets. The first corpse hits the pavement in the novel’s first few pages, and the bodies pile up so fast and so high that the Op himself loses count at 19 or so.

Amid the mounting carnage, the Op manages to stay alive by playing the murderous thugs and on-the-take cops against one another. Like Spade in The Maltese Falcon, the nameless detective, who is not afraid to ignore the letter of the law, uses the snares and tactics of his criminal adversaries to defeat them at their own game.

Hollywood made only one ill-fated attempt to translate Hammett’s book to the screen, in the little-seen early 1930 talkie Roadhouse Nights. The Op became a newspaperman played by comic actor Charlie Ruggles, and the film itself dispensed with most of the plot to become a vehicle for two singers, Helen Morgan (the star of Show Boat on Broadway) and vaudevillian Jimmy Durante.

It was left to Japanese director Akira Kurosawa and his co-screenwriter Ryuzo Kikushima to make the first, savage movie version of Red Harvest, 31 years later, as Yojimbo (The Bodyguard).

Transplanting the action to provincial Japan in 1860 and dramatically paring down Hammett’s byzantine plot, the movie follows the machinations of a lone ronin – a masterless samurai – who wanders into a nearly deserted town ravaged by violence and disorder. (Played by Kurosawa’s frequent star Toshiro Mifune, he assumes the moniker “Sanjuro,” though his true name is never known.) Deserted by its law-abiding citizens, the city is being torn apart by conflict between a pair of rival gangs in the service of two wealthy adversaries, a sake brewer and a silk merchant.

All the elements that would reappear in later versions of the story are in place here. A master swordsman, Sanjuro sells his services to both sides in the conflict, flip-flopping his loyalties from one minute to the next. His only ally is the town saloon keeper. He slyly rescues a married woman who has been taken as a hostage and concubine by one of the bosses and reunites her with her husband.

His deception is uncovered, and – in a sequence drawn from another serialized Hammett novel, The Glass Key (1931) – he is beaten nearly to death before making a dramatic escape, during which he witnesses the wholesale extermination of one of the gangs. Finally recovered from his wounds, he has a climactic duel with the other gang and its punk second-in-command Unosuke (Tatsuya Nakadai), who owns the only pistol in the town.

Yojimbo was a great enough success that it spawned a sequel, the comedic Sanjuro, in 1962. Perhaps more importantly, a 1963 screening of Kurosawa’s original film at the Arlecchino cinema in Rome inspired a B-movie director to make a Western adaptation, which failed to credit its samurai derivation.

Sergio Leone’s low-budget 1964 feature A Fistful of Dollars – perhaps not the first “spaghetti Western,” but certainly the most famous – translated the elements of Kurosawa’s story to the fictitious Mexican border town of San Miguel. “Sanjuro” became a poncho-clad Western gun-for-hire played by Clint Eastwood, late of the American TV series Rawhide. (Though one character refers to Eastwood’s character as “Joe,” ads for the American release of the film pegged him as “The Man With No Name.”)

The battling factions of Kurosawa’s picture became two outlaw gangs tussling for control of the city, the Rojos (Mexicans) and the Baxters (Americans). The mercenary anti-hero’s main adversary, patterned after Unosuke, was the crazed Winchester rifle-wielding Ramon Rojo, played by the masterful Italian actor Gian Maria Volonte (incongruously billed as “Johnny Wels”). With one major plot addition – the massacre of a Mexican army detachment by the Rojos’ gang – the feature followed Kurosawa’s film point by point, with a uniquely gritty, sunbaked look and operatic approach that set the spaghetti Western style for all time.

Noting Red Harvest as the source of Yojimbo, Leone said in a 1971 interview, “What I wanted to do was to undress these [Japanese] puppets, and turn them into cowboys, to make them cross the ocean and to return to their place of origin.”

But Leone paid the price for his piracy. Sued for plagiarism by Kurosawa – who remarked in a letter to the Italian filmmaker, “[A Fistful of Dollars] is a very fine film, but it is my film” – he was forced to surrender 15% of the worldwide gross and turn over distribution rights of his film in Japan and the Far East to the Japanese director’s company. Undaunted, Leone brought back the Man With No Name in a pair of larger-scaled, more violent sequels, For a Few Dollars More (1965) and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966), with Eastwood returning in his career-making role.

Oddly enough, the slam-bang action of Red Harvest and the heady box office receipts of its two adaptations did not inspire an American rendering of the story for decades. And, when it finally reached the screen for the first time, the tale ended up as an original pastiche of two Hammett novels.

Written by brothers Joel and Ethan Coen – who had used a phrase borrowed from Red Harvest as the title of their 1984 debut feature Blood Simple – and directed by Joel Coen, Miller’s Crossing reinstated the Prohibition-era setting of Hammett’s stories. The gang war conflict of Red Harvest is staged in the Coens’ feature between Irish mobster Leo O’Bannon (Albert Finney) and his Italian rival Johnny Caspar (Jon Polito), who come to blows over the activities of Jewish bookie Bernie Bernbaum (John Turturro).

However, the film’s stormy central relationship, between O’Bannon and his fixer, friend, and confidant Tom Reagan (Gabriel Byrne), replicates the alliance between mobbed-up political boss Paul Madvig and his faithful right-hand man Ned Beaumont, who fends off gangster Shad O’Rory’s power play in The Glass Key.

Despite its obvious derivations from Hammett’s books, Miller’s Crossing was a wholly original piece of work that transcended the uncredited glosses on its sources. The same could not be said for the other gangster-pic adaptation, Last Man Standing, which, while it more or less restored Hammett’s original setting, credited the Kurosawa-Kikushima script for Yojimbo as its inspiration.

Bruce Willis plays a freelance gunman calling himself “John Smith” – a name that draws cackles from his foes – who rolls into the Depression-era Texas border town of Jericho in a Model T Ford, packing two shoulder-holstered .45s and an immutably sullen expression. Dressing the ceaseless violence of the plot in a dusty neo-Leone palette, writer-director Walter Hill trots through Yojimbo’s original plot points, turning the warring factions into rival bootleggers (Irish and Italian, of course) and tacking on the massacre from A Fistful of Dollars to lift the body count.

Willis’ Smith is the putative hero of the piece, and, while he rescues the damsel in distress like his samurai and spaghetti Western predecessors, his relentless misogyny and utter humorlessness, and the actor’s silly, open-mouthed “shootout face,” make him a difficult figure to root for. The lone bright spot in the picture is the reliably weird Christopher Walken’s chilly turn as the scar-faced top gunman Hickey, a clone of his psycho precursors Unosuke and Ramon Rojo, who wields a Tommy gun instead of a pistol or a repeating rifle.

Last Man Standing is a poor excuse for an American rendering of Red Harvest, and it leaves one hoping that someday a truly gifted director will take up Hammett’s grimly funny, dark novel and its pudgy, boozy, cagey hero and give them the widescreen homegrown treatment they deserve. The book is an American classic, and it deserves a rendering in its own, long-buried name.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sex Pistols, SF, 1/14/78

This very bad piece of writing, which I wrote as the whey-faced “Los Angeles correspondent” for a Wisconsin music rag, is posted in the interest of music history. When last seen, the group’s lead vocalist was featured on “The Masked Singer.”

**********

The Sex Pistols

“Notes From New Babylon,” Emerald City Chronicle, Feb. 7-21. 1978

Los Angeles, January 17, 1978

In San Francisco on Saturday, the Sex Pistols proved that they don’t fire blanks. And the crowd shot back.

The last date on the Pistols’ eight-day American tour was held before 5,000 people in that bastion of hippiedom, Winterland. With the hall’s bright red floor and tiered seating conjuring up a high school gym, the concert resembled nothing so much as a junior high dance held on Mars.

The Faithful, the True Believers were out in force. With a couple of busy punk venues and a number of homegrown New Wave phenoms to its credit, San Francisco has learned over the last year to dress and act the punk part.

Although the majority of the audience consisted of curious booboisie ready to gawk at this year’s New Thing, there were large numbers of Real Fans decked out to the teeth. The “haute couture” came courtesy of Gillette, Johnson and Johnson, and Handy Trash Bags. They came in see-through plastic raincoats, t-shirts torn, stapled and safety-pinned, vertigo-inducing patterned shirts and blouses, berets, sunglasses of every configuration and color, and leathers of every persuasion. The hairdos were chopped and channeled and tinted red, pink, green, yellow, orange, spikey like the coiffures of electrocuted felons. Scott Mackenzie go home – flowers and beads have long been consigned to the trash, and Love City’s torn down. A New Wave has hit North Beach.

I grabbed a spot about 25 feet in front of the stage and waited out the opening acts, two local groups, the Nuns and the Avengers, both determined to outlast their welcome. The highlight of the first two hours was drunken rock critic/”musician” R. Meltzer’s attempt to incite the crowd with a string of addled and half-hearted obscenities. The crowd got some early target practice, and Meltzer was led from the scene by an impatient Bill Graham.

The Pistols arrived at 10:15.

Bassist Sid Vicious took the stage first. When Vicious finally doffed his knee-length greatcoat, he displayed a body covered with livid scars; a fresh bandage shielded a recent wound. What Vicious, self-styled “worst bass player in the world,” lacks in musical expertise, he makes up for with his winning personality.

During the set, he showered the audience with ropes of spittle, spat beer on the front row, verbally invited ringsiders to spar with him, and in general displayed manners that Amy Vanderbilt would consider sub-par. The security crew on his side of the stage stayed busy all night. He survived.

Steve Jones, the pudgy guitarist, took a stance of pugnacious cool. Looking the low-life toff in a cherry-red coat, he sneered, strutted, jumped and spat this way through the set, oblivious to the return fire. Spit hung from his face like a veil of Spanish lace. Through it all, his axe barked like a wounded creature.

Drummer Paul Cook bashed his way along, unaware of the barrage that rattled his cymbals and smacked his bass drum.

Last to join the fray was John Rotten.

Oh, Johnny Rotten, most scabrous of rock and rollers. Your heart goes out to this wretched soul with his Day-glo pallor and drawn, acned visage. He lurches out in Gestapo leather, leather pants festooned with chains, two vests, white shirt. But forget the fashion – the first thing you notice as he hunches over the mike are his brilliant blue eyes, freezing with malice, riveting you to the Winterland floor when they shoot your way.

He greets the crowd. “Welcome to London.”

Thus begins an hour-long salvo in which the audience shows their feverish affection by launching every object in their possession at the stage in a true love-hate gesture. You name it, beer cans, fruit both fresh and rotten, stink bombs, a box of Tampax, toilet paper, a dispenser of birth control pills, shoes, skirts, pieces of tattered clothing, loose change, chains, safety pins, a squirt gun, anything throwable, an unrelenting storm for 60 minutes. “The stuff yer throwin’ ain’t good enough,” complains John Rotten, and two umbrellas sail onto the stage. “‘At’s more like it, now throw some cameras, we can use some nice cameras.” Each object is scrupulously examined and sometimes pocketed by the singer.

Ignoring the bombardment of foreign matter and the thunderstorm of hockers from the first rows, the Pistols hammered through thirteen balls-to-the-wall rockers in their formal set – eleven songs from Never Mind the Bollocks, one B-side (“I Wanna Be Me,” the flip of “Anarchy in the U.K.”), and one new tune. Each note vibrated with anger. Rotten communicates it all. He may be the most visceral performer I’ve ever seen; his performance wracks his voice, body and spirit so, you’re afraid he’ll collapse right in front of you.

Each song as performed live was a new epiphany, animated by that paralyzing stare and crook-backed accusation that is uniquely John Rotten. Perhaps the finest hour came in “Pretty Vacant,” as the staccato opening lick, repeated and repeated, insinuated and finally exploded. Jone and Vicious jumping up, the crowd screaming, as the band plunged into the ultimate anthem of the True Lost Generation, the Blank Generation of the Seventies.

The group closed with “Anarchy in the U.K.,” retooled to read “Anarchy in the U.S.A.” After a pause, they returned, in a bow to their greatest American influence, they performed an exhausting workout on Iggy’s “No Fun.” Rock of Ages, let me hide myself in thee

Paul and Steve drag a groupie up from the crowd, Paul latches a hand onto her butt and leers back at the crowd, Sid trades last endearing words with the front row, Rotten pulls himself from the floor and beats an agonized retreat, and the Sex Pistols Tour of the Americas is over.

Verdicts? Delirium from the Acolytes, boredom, confusion and indifference from the Fleetwood Frampton clones. You know where I stand, and if you don’t have a place to stand, you might as well find a place to lie down. They might not be the new Beatles (thank god for that), but the Sex Pistols have revitalized rock and roll for me in the deathly Seventies.

P.S. (1/25/78) From where I sit, it looks like the Sex Pistols may be finished. Daily Variety and the L.A. Times said, yes, it’s all over last Thursday. On Sunday, the Pistols’ U.S. rep was denying it all on local radio, but the denial had a kind of uninformed, hollow ring to it.

Mid-last week, John Rotten went before the press and said that the band was splitting, that he was tired of the “big band” hype the group received on its American tour. A couple of local observers here feel that this is just a ploy to remove Sid Vicious, whose behavior suggests that he might be a potentially dangerous psychopath, but I personally doubt it.

So what, you ask. The Pistols haven’t been around long enough to matter to a lot of people, but they have set the trend. With the wheels in motion, there is now a movement to continue without them. My feelings are that it’s too bad, a great band is going down prematurely, but John Rotten will still be around to be a star. A star IN SPITE OF HIMSELF.

Long live the Pistols.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rock Gunfight in the Antipodes

Listening today to the hot new Grown Up Wrong! comp by Sydney’s Lipstick Killers, whose lone officially released single was produced by Deniz Tek of Radio Birdman, it occurred to me that my old Music Aficionado faux faceoff between Australia’s pioneering bands of the ‘70s (all of which I dearly love) has disappeared into the online ether. It’s time to bring it back.

**********

By Chris Morris

The mid- to late ‘70s were fertile days for rock ‘n’ roll in Australia. Here and there across the vast but not terribly populous island continent, fires were started by several attitude-filled bands bent on doing things their own damn way. They all managed to make their way off the island, but if they hit the American consciousness, it was for little more than a nanosecond during their heyday.

Who were the truest Rock Wizards of Oz? For this Down Under face-off, I’ve selected three contenders: the Saints, Radio Birdman, and the Scientists. All of them had fairly slim discographies; ironically, the act probably least known in the U.S., the Scientists, recorded most prolifically, with their core line-up producing several magnificent albums and singles during a productive four-year stretch in the early ‘80s. But none of these bands ever stayed together long enough to make a deep impression among the Yanks.

So where’s the Birthday Party, you ask? There are a few things to consider. First of all, though the band and its precursor unit the Boys Next Door were in business from 1976 on, they didn’t release their first LP until 1980. Also, Nick Cave is well known enough that more (king) ink needn’t be spilled on him. Finally, I still resent the fact that Cave stole PJ Harvey away from me, so it’s personal.

On with the showdown…

HIT ME LIKE A DEATH RAY, BABY

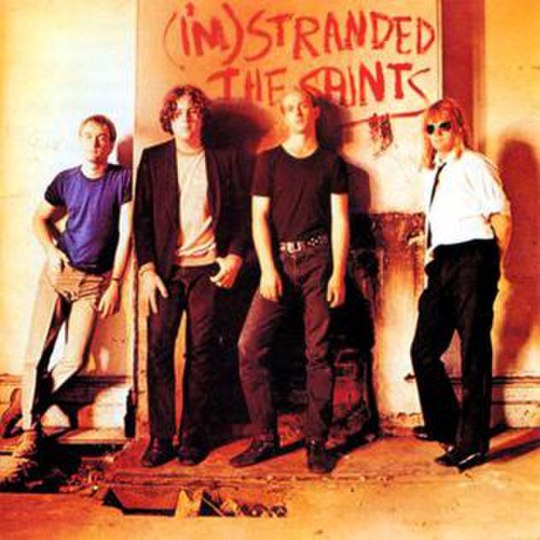

The Saints, founded 1974 in Brisbane

The prime movers of the Saints were a pair of literal outsiders: vocalist Chris Bailey, born in Kenya to Irish parents, and guitarist Ed Kuepper, raised in Germany. Thus the otherness of their work is no surprise.

With schoolmate Ivor Hay – who over time would play drums, bass, and piano with them – the pair founded a combo originally known as Kid Galahad and the Eternals (borrowing their handle from a 1962 Elvis Presley picture), but they swiftly renamed themselves the Saints and began playing in their hometown on the northeast coast of Australia.

Listening to their records, which were made in something of a cultural vacuum, it’s difficult to get a handle on where the Saints’ distinctive, aggressive sound came from. To be sure they were aware of such homegrown precursors from the ‘60s as the Master’s Apprentices and the Missing Links (whose 1965 single they covered on their debut album). It’s safe to assume they were conversant with the Velvet Underground, the Stooges, and Lenny Kaye’s 1972 garage rock compilation Nuggets. Yet they bred something utterly their own in the ocean air of Brisbane.

With Hay on drums and Kym Bradshaw on bass, Bailey and Kuepper mounted noisy local gigs that swiftly attracted the antipathy of the local constabulary; they wound up turning their own digs into a club to play shows. In 1976, they recorded and issued a self-financed single featuring two originals, “(I’m) Stranded” and “No Time.” These dire, ferocious songs were distinguished by venomous lyrics, unprecedented velocity, and guitar playing by Kuepper that sounded like a (literal) iron curtain being attacked with a chainsaw.

The record died locally, but a copy of its U.K. issue found its way into the hands of a critic at the English music weekly Sounds, which declared it the single of the week. This accolade got the attention of EMI Records, which signed the band and financed the recording of an album, also titled I’m Stranded, in a fast two-day Brisbane session.

The album, which was ultimately released in the U.S. by Sire Records, blew the ears off anyone who heard it, and it landed with a bang in England, where punk rock was lifting off in all its fury in early 1977. It was hurtling, powerful stuff that stood apart from punk in several crucial ways: While some of the songs were clipped and demonic in the standard manner, the Saints proved they could take their time on expansive numbers like the almost Dylanesque “Messin’ With the Kid” and the sprawling, hellriding “Nights in Venice.” And one has to wonder how British p-rockers took to their perverted take on Elvis’ squishy “Kissin’ Cousins.”

Made by musicians who never considered themselves “punks,” and who in fact abhorred the label, (I’m) Stranded is nevertheless one of the definitive statements in the genre, and it has maintained its force to this day.

Settling in England for the duration, the Saints decided to throw a curveball. One could not find a more profoundly alienated album than Eternally Yours (1978), a series of yowling protests, twisted prophecies, and savage put-downs, including the snarling second version of the single “This Perfect Day.” But, though the record was loud and for the most part swift, the group applied the brakes to their sound somewhat, and a couple of songs, including the caustic album opener “Know Your Product,” were dressed by a soul-styled horn section. Punk loyalists ran for cover.

By the time Prehistoric Sounds was issued in late ’78, the dejected Bailey and Kuepper were moving in different directions, and you can hear it in the grooves. The record is slow, almost listless at times, and its logy originals are complemented by incongruous Otis Redding and Aretha Franklin covers with none of the energy of earlier Saints soul-blasts. It is an album primarily for loyalists, and by then there were few in that number.

Kuepper exited the band on the heels of the third album’s release and returned to Australia, where he enjoyed a long career as leader of the Laughing Clowns; Bailey continued to perform under the Saints mantle with a shifting lineup that at last count numbered more than 30 players over the course of 37 years

Bailey and Kuepper reunited for one-off gigs in 2001 (at the ARIA awards ceremony) and 2007 (at Australia’s Queensland Music Festival).

THERE’S GONNA BE A NEW RACE

Radio Birdman, founded 1974 in Sydney

People who toss the “punk” handle around often throw Radio Birdman into the mix, but the sextet from Australia’s Southeast Coast may be best referred as the world’s youngest proto-punk band.

Its mastermind was guitarist, songwriter, and producer Deniz Tek, a native of Ann Arbor, Michigan, who emigrated to Sydney in 1971 to study medicine. As a teen, he got a chance to witness Detroit’s most explosive pre-punk bands – the MC5, the Stooges, and the Rationals; he would later wind up collaborating with important members of all those groups.

After apprenticing with and getting bounced from a Sydney band called TV Jones, Tek formed Radio Birdman (its name a corruption of a lyric from the Stooges’ “1970”) with singer Rob Younger; the lineup ultimately solidified with the addition of guitarist (and sometime keyboardist) Chris Masuak, bassist Warwick Gilbert, drummer Ron Keeley, and (on and off and then on again) keyboardist Pip Hoyle.

Rapidly acquiring a fan base made up of some of Sydney’s lowest elements, including members of the local Hell’s Angels, Radio Birdman ultimately took over a bar, re-dubbed (in honor of the Stooges, of course) the Oxford Funhouse, as their base of operations. The band’s severe Tek-designed band logo emanated fascist-style vibes for some; at a co-billed appearance in Sydney, the Saints’ Chris Bailey remarked from the stage, “We’d like to thank the local members of Hitler Youth for their stage props.”

Despite much antipathy and some attendant violence, the band maintained a loyal local following, and in 1976 it issued a strong four-song EP, Burn My Eye, via local studio-cum-independent label Trafalgar. This was succeeded the following year by a full-length debut album, Radios Appear.

Anyone looking for something resembling punk will likely be disappointed by that collection. The band wears its all-American hard rock/proto-punk influences on its dirty sleeve. Radios Appear is dedicated to the Stooges (whose “No Fun” was the lead-off track on the Aussie issue of the LP), and a song co-written by Tek and Stooges guitarist Ron Asheton, “Hit Them Again,” was cut during sessions for the record. Tek pays deep homage to MC5 guitarist Wayne Kramer with his playing, and blatantly cops a signature lick from the 5’s “Looking at You” at one juncture. The album title was lifted from a Blue Öyster Cult lyric, and the Tek-Masuak guitar-bashing bows to their multi-axe sound. Finally, in both Younger’s sometimes Morrisonian vocalizing and Hoyle’s Ray Manzarek-like ornamentation, homage to the Doors in paid in full. Given that Sydney is a beach town, there’s even a frisson of surf music in the mix.

Bursting with power-packed originals like the apocalyptic “Descent into the Maestrom,” youth-in-revolt anthem “New Race,” the cryptic, insinuating “Man with the Golden Helmet,” and Tek’s autobiographical “Murder City Nights,” Radios Appear was a power-packed set that established Radio Birdman as Oz’s leading rock light.

However, renown did not equal success in Antipodean terms. In 1978, the band cut its second album, Living Eyes, at Rockfield Studio in Wales; it was a solid effort that included remakes of three Burn My Eye numbers (including the wonderful Tek memoir “I-94,” about the Michigan interstate) and excellent new originals like “Hanging On,” “Crying Sun,” and “Alone in the End Zone.” But, with success seemingly within their grasp, Sire Records – their American label, and the Saints’ as well – switched distribution and cut their roster, leaving their new work without a home. Within months of this catastrophe, Radio Birdman disbanded.

The principals scattered, to Younger’s New Christs and Tek and Hoyle’s the Visitors; Tek, Younger, and Warwick Gilbert later joined MC5 drummer Dennis Thompson and the Stooges’ Ron Asheton in the one-off New Race. Tek also later recorded with Wayne Kramer and Scott Morgan of Ann Arbor’s Rationals in Dodge Main.

Radio Birdman’s original lineup reunited for a 1996 tour; in August 2006 – after four of the original sextet regrouped to record a potent new album, Zeno Beach – the band played its first American date ever, at Los Angeles’ Wiltern Theater. Your correspondent was there, and it was freakin’ incredible.

IN MY HEART THERE’S A PLACE CALLED SWAMPLAND

The Scientists, founded 1978 in Perth

Among the important Aussie bands of the ‘70s, the Scientists were among the first to be directly influenced by the punk explosion in New York.

As guitarist-singer-songwriter Kim Salmon – the lone constant in the Scientists’ lineup during their existence – wrote in 1975, “Reading about a far-off place called CBGB in NYC and its leather-clad denizens, all with names like Johnny Thunders, Richard Hell, and Joey Ramone, got me thinking…I immediately went searching for Punk Rock. What I found were The Modern Lovers and The New York Dolls albums.”

Salmon first dabbled in the new sound with a band bearing the delightfully punk name the Cheap Nasties. Cobbled together in Perth – the Western provincial capital of Australia – from members of such local acts as the Exterminators, the Victims, and Salmon’s the Invaders -- the early Scientists were as derivative as one might imagine. Their early songs, heard on their self-titled LP (the so-called “Pink Album”) and an early single and EP, sport original songs authored by Salmon and drummer-lyricist James Baker, the backbone of shifting Scientific crews through 1980. The tunes range from straight-up Dolls/Heartbreakers rips (“Frantic Romantic,” “Pissed On Another Planet,” “High Noon”) to buzzing romantic pop-punk in a Buzzcocks vein (“That Girl,” “She Said She Loves Me”).

Not terribly promising stuff, but, after the departure of Baker for the Hoodoo Gurus in 1981 and a brief stint in a trio called Louie Louie, Salmon assembled a new Scientists who would prevail for nearly four years. That outfit – Salmon, guitarist Tony Thewlis, bassist Boris Sujdovic, and drummer Brett Rixton – promptly relocated to Sydney and started making the noise they are noted for.

By that time, Salmon had begun cocking an ear to the Birthday Party (and no doubt paid careful attention to the sordid noise on the Melbourne group’s 1982 album Junkyard), had discovered the miasmic voodoo of the Cramps, and started grooving to the dissonant, slide guitar-dominated racket of Captain Beefheart and his Magic Band. In short order, he would also absorb the bluesy downhome assault of Los Angeles’ roots-punk outfit the Gun Club.

The Sydney-based Scientists hooked up with indie label Au Go Go, which issued a devastating run of careening, mossy records by the band in 1982-83 – the vertiginous singles “This is My Happy Hour”/“Swampland” and the corrosive “We Had Love” (backed by a faithful cover of Beefheart’s “Clear Spot”), and the heart-stopping mini-album Blood Red River, which bore the churning “Set It On Fire,” “Revhead,” and “Burnout.” Others were essaying a similar style, but the Aussie youngsters were beating their elders at their own game.

Eying the big time, the band moved to London in 1984. Some opportunities presented themselves initially: The band got European tour slots with the Gun Club and early Goth act Sisters of Mercy. But their deal with Au Go Go fell apart acrimoniously; while they made a pair of fog-bound albums, You Get What You Deserve (1985) and The Human Jukebox (1987) for Karbon Records (and a set of re-recorded songs, Weird Love, was issued in the U.S. by Big Time Records), they scraped by in Britain.

Defections from the ranks commenced in ’85, and by early 1987 the depleted Salmon used money from a housing settlement to move back to Australia, where he founded a new band, the Surrealists.

Still valued among the cognoscenti, Salmon, Thewlis, Sujdovic, and latter-day drummer Leanne Chock appeared, at the invitation of Seattle’s Mudhoney, at London’s All Tomorrow’s Parties Festival in 2006. Earlier this year, Chicago-based archival label the Numero Group issued a comprehensive four-disc box of the band’s original recordings.

So, at the end of the day, who is the all-time champeen of ‘70s Oz rock?

Scoring on points, the Saints are tops for Being Punk First with additional wins in the Pure Noise and Weltzschmerz categories, Radio Birdman takes the Technical Ability and Old-School Attitude slots, and the Scientists prevail in the Loud Young Snot and Grunge Thug division.

And the championship belt goes to…the Saints!

Of course, that could all change tomorrow, but that’s rock ‘n’ roll for ya.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Moby Grape: Rock ‘n’ Roll Tragedy

Methinks it’s time to restore this old Music Aficionado post about the great SF band to the Interwebs.

**********

In 1966, amid the ferment of San Francisco’s active music scene, five disparate musicians were brought together in a new band. Heavily laden with talent, the group cut a 1967 debut album that is still ranked among the finest, most assured bows in rock history. Almost instantly, they were tabbed as the act to beat.

Yet, if it’s recalled at all today, Moby Grape’s name is synonymous among rock connoisseurs with tragedy, failure, unfulfilled promise, and chaos. The story of how what appeared to be rock’s Perfect Beast became a rolling catastrophe is one of the all-time cautionary tales in the annals of music and the music business.

One looks back at Moby Grape and wonders, “How could they fail?” Among performing units of their era, they were seemingly rivaled solely by their Los Angeles contemporaries Buffalo Springfield, whose glittering lineup included the mighty singer-songwriter-guitarist triumvirate of Neil Young, Stephen Stills, and Richie Furay.

Moby Grape trumped the Springfield’s three-pronged attack. All five members of the group sang, and they forged a deftly blended choral attack unique among bands of the day. All five musicians also wrote, with consistent brilliance and economy. Their three-guitar front line could blow any outfit unlucky enough to share a stage with them right off the boards, and their powerful rhythm section was unmatched by any on the Haight-Ashbury scene.

So what the hell happened? How did Moby Grape, anointed upon arrival as possibly the best Frisco had to offer in that city’s glory days, run aground?

The seeds of the band’s disorder may have been sown in its founding. In late 1966, its five members were brought together by an ambitious manager seeking a new act to work, as major label A&R men began poking around for acts that were playing in San Francisco’s burgeoning rock ballroom scene. (More will be said about that manager in a while.)

The magnetic linchpin of the new band was singer-songwriter-guitarist Skip Spence. The Canadian musician had served as the drummer for Jefferson Airplane and had played on the group’s debut album Jefferson Airplane Takes Off. However, feeling marginalized creatively in the Airplane, he abruptly quit the band for a sojourn in Mexico. On his return to the Bay Area, he linked up with the Airplane’s erstwhile manager to make a fresh start.