Quote

How I love those boats as they start to race, like horses chasing one another.

The neck of the river was unadorned before, but now, in the darkness of night, it is all

decked out.

The brightness of the boats’ candles is as the brilliance of stars; you’d think their

reflections were lances in the water.

Many boats are moved along by their sail wings and others by their oar feet; they look

like frightened rabbits fleeing from falcons.

Ibn Lubbal, Jerez (d. 1187 CE)

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

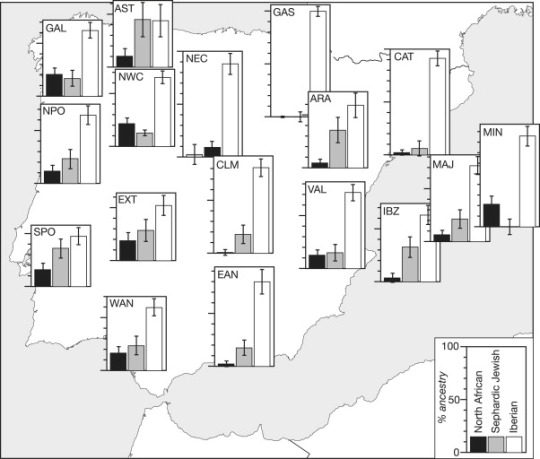

Iberian, North African, and Sephardic Jewish Admixture Proportions among Iberian Peninsula Samples.

28 notes

·

View notes

Photo

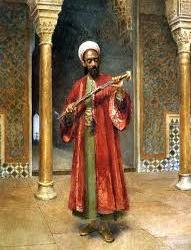

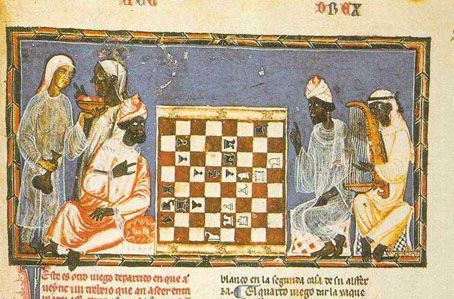

When African Men Ruled the World: 8 Things The Moors Brought to Europe

When the topic of the Moorish influence in Europe is being discussed, one of the first questions that arises is, what race were they?

As early as the Middle Ages, “Moors were commonly viewed as being mostly black or very swarthy, and hence the word is often used for negro,” according to the Oxford English Dictionary.

Author and historian Chancellor Williams said “the original Moors, like the original Egyptians, were Africans.”

The 16th century English playwright William Shakespeare used the word Moor as a synonym for African. His contemporary Christopher Marlowe also used African and Moor interchangeably.

Arab writers further buttress the black identity of the Moors. The powerful Moorish Emperor Yusuf ben-Tachfin is described by an Arab chronicler as “a brown man with wooly hair.”

African soldiers, specifically identified as Moors, were actively recruited by Rome, and served in Britain, France, Switzerland, Austria, Hungary, Poland, and Romania. St. Maurice, patron saint of medieval Europe, was only one of many African soldiers and officers under the employ of the Roman Empire.

Although generations of Spanish rulers have tried to expunge this era from the historical record, recent archeology and scholarship now shed fresh light on the Moors who flourished in Al-Andalus for more than 700 years – from 711 AD until 1492. The Moorish advances in mathematics, astronomy, art, and agriculture helped propel Europe out of the Dark Ages and into the Renaissance.

Source: Stewartsynopsis.com/moors_in_europe.htm

Universal Education

The Moors brought enormous learning to Spain that over centuries would percolate through the rest of Europe.

The intellectual achievements of the Moors in Spain had a lasting effect; education was universal in Moorish Spain, while in Christian Europe, 99 percent of the population was illiterate, and even kings could neither read nor write. At a time when Europe had only two universities, the Moors had seventeen, located in Almeria, Cordova, Granada, Juen, Malaga, Seville, and Toledo.

In the 10th and 11th centuries, public libraries in Europe were non-existent, while Moorish Spain could boast of more than 70, including one in Cordova that housed hundreds of thousands of manuscripts. Universities in Paris and Oxford were established after visits by scholars to Moorish Spain.

It was this system of education, taken to Europe by the Moors, that seeded the European Renaissance and brought the continent out of the 1,000 years of intellectual and physical gloom of the Middle Ages.

Source: Blackhistorystudies.com/resources/resources/15-facts-on-the-moors-in-spain/

Culturespain.com/2012/03/02/what-did-the-moors-do-for-us/

Fashion and Hygiene

Abu l-Hasan Ali Ibn Nafi – who was also known as Ziryab (black singing bird in Arabic) and Pájaro Negro (blackbird) in Spanish- was a polymath, with knowledge in astronomy, geography, meteorology, botanics, cosmetics, culinary art and fashion. He is known for starting a vogue by changing clothes according to the weather and season. He also suggested different clothing for mornings, afternoons and evenings.

He created a deodorant to eliminate bad odors, promoted morning and evening baths, and emphasized maintaining personal hygiene. Ziryab is believed to have invented an early toothpaste, which he popularized throughout Islamic Iberia – primarily in Spain.

He made fashionable shaving among men and set new haircut trends. Royalty used to wash their hair with rosewater, but Ziryab introduced salt and fragrant oils to improve the hair’s condition.

Source: Wikipedia.org/wiki/Ziryab

Cuisine

Ziryab was also an arbiter of culinary fashion and taste, and revolutionized the local cuisine by introducing new fruit and vegetables such as asparagus, and by initiating the three-course meal served on leathern tablecloths. He insisted that meals should be served in three separate courses consisting of soup, the main course, and dessert.

He also introduced the use of crystal as a container for drinks, which was more effective than metal. Prior to his time, food was served plainly on platters on bare tables, as was the case with the Romans.

In general, the Moors introduced many new crops including the orange, lemon, peach, apricot, fig, sugar cane, dates, ginger and pomegranate as well as saffron, cotton, silk and rice, all of which remain prominent in Spain today.

Source: Wikipedia.org/wiki/Ziryab

Urban Utilities: Street lights, Hospitals and Public Baths

In the 10th Century, Cordoba was not just the capital of Al Andalus (Moorish Spain) but also one of the most important cities in the world, rivaling Baghdad and Constantinople. It boasted a population of 500,000 (200,000 more than now) and had street lighting, fifty hospitals with running water, three hundred public baths, five hundred mosques and seventy libraries – one of which held over 500,000 books.

The Moorish achievement in hydraulic engineering was outstanding. They constructed an aqueduct, that conveyed water from the mountains to the city through lead pipes.

All of this, at a time when London had a largely illiterate population of around 20,000 and had forgotten the technical advances of the Romans some 600 hundred years before. Paved and lighted streets did not appear in London or Paris for hundreds of years later.

Source: Houseofnubian.com/IBS/SimpleCat/product/ASP/product-id/315094.html

Urban Utilities: Street lights, Hospitals and Public Baths

In the 10th Century, Cordoba was not just the capital of Al Andalus (Moorish Spain) but also one of the most important cities in the world, rivaling Baghdad and Constantinople. It boasted a population of 500,000 (200,000 more than now) and had street lighting, fifty hospitals with running water, three hundred public baths, five hundred mosques and seventy libraries – one of which held over 500,000 books.

The Moorish achievement in hydraulic engineering was outstanding. They constructed an aqueduct, that conveyed water from the mountains to the city through lead pipes.

All of this, at a time when London had a largely illiterate population of around 20,000 and had forgotten the technical advances of the Romans some 600 hundred years before. Paved and lighted streets did not appear in London or Paris for hundreds of years later.

Source: Houseofnubian.com/IBS/SimpleCat/product/ASP/product-id/315094.html

Human Flight

The Moors’ scientific curiosity extended to flight when polymath Ibn Firnas made the first scientific attempt to fly in a controlled manner, in 875 A.D. His attempt evidently worked, although the landing was less successful.

Source: Culturespain.com

Advance Agriculture Techniques

Under the Moors, Spain was introduced to new food crops such as rice, hard wheat, cotton, oranges, lemons, sugar and cotton. More importantly, along with these foodstuffs came an intimate knowledge of irrigation and cultivation of crops. The Moors also taught the Europeans how to store grain for up to 100 years and built underground grain silos.

Source: Houseofnubian.com

Paper Making

Paper making was brought to Spain by the Moors, allowing the growth of libraries and, thereby, the accurate preservation and dispersal of knowledge – with Xativa, in Valencia, having the first paper factory in Europe.

Through the Moorish conquest of southern Spain, paper making first reached the Moorish parts of Spain in the 12th century. A paper mill is recorded at Fez in Morocco in 1100, and the first paper mill on the Spanish mainland is recorded at Xàtiva in 1151.

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

THE VOICE OF MAGDALENE || [8TRACKS] [PLAYMOSS] [SPOTIFY]

A newly re-edited playlist of mine featuring music composed and performed by women in the medieval era. The mix contains both religious and secular music from Western Europe, Armenia, Byzantium, and Al-Andalus. All pieces date between the 8th and 15th centuries.

Zarmani e Ints | Khosrovidukht (8th Century)

Avgoustou Monarchisantos | Kassia (810-865)

O Vis Aeternitatis | Hildegard von Bingen (1098-1179)

Mout M'abelist Quant le Voi | Maroie de Dregnau de Lille (13th Century)

Kharjas: Non Me Mordas Ya Habibi | Andalusian Anon. (13th Century)

Sol Oritur Occasus Nescius | Herrad of Landsberg (1130-1198)

A Chantar M’er de So Qu'eu no Volria | Comtessa de Dia (1140-1212)

Saltarello: “La Regina” | Italian Anon. (14th Century)

Amours, ou Trop Tart me Sui Pris | Attributed to Blanche of Castile (1188-1252)

Na Maria | Bieiris de Romans (early 13th Century)

Conductus: Ave Maris Stella | From the “Las Huelgas Codex” (13th Century)

Kharjas: Adir la-na Akwab | Andalusian Anon. (13th Century)

Si'us Qu'er Conselh Bela Amia Alamanda | Giraut de Bornelh (1138-1215) and

Alamanda de Castelnau (1160?-1223)

Mout Avetz Fach | Castelloza (early 13th Century)

Deuil Angoisseus | Christine de Pizan (1364-1430) and Giles Binchois (1400-1460)

Antiphon: Caritas Habundant in Omnia | Hildegard von Bingen (1098-1179)

Mon Chevalier, mon Gracieux Servant | Christine de Pizan (1364-1430)

Image: Sculpture of Mary Magdalene by Gregor Ernhart (c.1502), The Louvre.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

This is the sword of Abdullah al-Saghir - The last King of Granada.

Al-Andalus - ( Andalusia of the Islamic period ) - Golden Era of Andalusia

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

“La ignorancia lleva al miedo, el miedo lleva al odio, y el odio lleva a la violencia. Ésa es la ecuación.”

By Averroes (Ibn Rushd)

“Ignorance leads to fear, fear leads to hate, and hate leads to violence. This is the equation.”

42 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Tanto amare, tanto amare, / habib, tanto amare:

¡Enfermaeron welyos nidios / e dolen tan male!

Yosef al-Katib (a Jewish scribe in early 11th-century Iberia). This panegyric (or kharja) was written for Abu-Ibrahim Semuel and his brother Ishaq. Many other kharjas were written by women in praise of their lovers, and they would sing them while wandering the streets. The language is Mozarabic, which is best thought of as an amalgam of the early Spanish and Arabic of al-Andalus.

Translation:

‘So much loving, so much loving, / my lover, so much loving

has made my bright eyes grow dim / and suffer so much!’

(via oakapples)

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ornament of the World

By Professor Maria Rosa Menocal as sent to me by David Shasha via Sephardic History Update. Professor Menocal recently passed away after a 3 year fight with melanoma.

A Golden Reign of Tolerance

By Maria Rosa Menocal

The lessons of history, like the lessons of religion, sometimes neglect

examples of tolerance. A thousand years ago on the Iberian Peninsula, an

enlightened vision of Islam had created the most advanced culture in Europe. A

nun in Saxony learned of this kingdom from a bishop, the caliph’s ambassador to

Germany and one of several prominent members of his diplomatic corps who were

not Muslims; the bishop most likely reported to the man who ran the foreign

ministry, who was a Jew.

Al Andalus, as the Muslims called their Spanish homeland, prospered in a

culture of openness and assimilation. The nun, named Hroswitha, called it “the

ornament of the world.”

Her admiration stemmed from the cultural prosperity of the caliphate based

in Cordoba, where the library housed some 400,000 volumes at a time when the

largest library in Latin Christendom probably held no more than 400. What

strikes us today about Al Andalus is that it was a chapter of European history

during which Jews, Christians and Muslims lived side by side and, despite

intractable differences and enduring hostilities, nourished a culture of

tolerance.

This only sometimes meant guarantees of religious freedoms comparable to

those we would expect in a modern “tolerant” state. Rather, it was the often

unconscious acceptance of contradictions on an individual level as well as

within the culture itself.

Much that was characteristic of medieval culture was rooted in the

cultivation of the charms and challenges of contradictions – of the “yes and

no,” as it was put by Peter Abelard, the provocative 12th-century Parisian

intellectual and Christian theologian. A century after his death, Abelard’s

heirs, Christian professors and students on the Left Bank of the Seine, were

among the most avid readers of the two great philosophers of Al Andalus: one

Jewish, Maimonides, and one Muslim, Averroes.

For many who came to know Andalusian culture throughout the Middle Ages,

whether at first hand or from afar – from reading a translation produced there

or from hearing a poem sung by one of its renowned singers – the bright lights

of that world, and their illumination of the rest of the universe, transcended

differences of religion. It was in Al Andalus that the profoundly Arabized Jews

rediscovered and reinvented Hebrew poetry. Much of what was created and

instilled under Muslim rule survived in Christian territories, and Christians

embraced nearly all aspects of Arabic style – from philosophy to architecture.

Christian palaces and churches, like Jewish synagogues, were often built in the

style of the Muslims, the walls often covered with Arabic writing; one synagogue

in Toledo even includes inscriptions from the Koran.

And it was throughout medieval Europe that men of unshakable faith, like

Abelard and Maimonides and Averroes, saw no contradiction in pursuing the truth,

whether philosophical or scientific or religious, across confessional lines.

This was an approach to life – and its artistic, intellectual and religious

pursuits – that was contested by many, sometimes violently, as it is today. Yet

it remained a powerful force for hundreds of years.

Whether it is because of our mistaken notions about the relative backwardness

of the Middle Ages or our own contemporary expectations that culture, religion

and political ideology will be roughly consistent, we are likely to be taken

aback by many of the lasting monuments of this Andalusian culture. The tomb of

St. Ferdinand, the king remembered as the Christian conqueror of the last of all

the Islamic territories, save Granada, is matter-of-factly inscribed in Arabic,

Hebrew, Latin and Castilian.

The caliphate was not destroyed, as our cliches of the Middle Ages would have

it, by Christian-Muslim warfare. It lasted for several hundred years – roughly

the lifespan of the American republic to date – and its downfall was a series

of terrible civil wars among Muslims. These wars were a struggle between the old

ways of the caliphate – with its libraries filled with Greek texts and its

government staffed by non-Muslims – and reactionary Muslims, many of them from

Morocco, who believed the Cordobans were not proper Muslims. The palatine city

just outside the capital, symbol of the wealth and the secular aesthetics of the

caliph and his entourage, was destroyed by Muslim armies.

But in the end, much of Europe far beyond the Andalusian world was shaped by

the vision of complex and contradictory identities that was first made into an

art form by the Andalusians. The enemies of this kind of cultural openness have

always existed within each of our monotheistic religions, and often enough their

visions of those faiths have triumphed. But at this time of year, and at this

point in history, we should remember those moments when it was tolerance that

won the day.

Maria Rosa Menocal is director of the WhitneyHumanitiesCenter at Yale and author of “The Ornament of the World: How Muslims, Jews and Christians Created a Culture of Tolerance in Medieval Spain.”

From The New York Times, March 28, 2002

26 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Worthy I am, by God of the highest, and

Proudly I walk with head aloft

My cheek I give to my lover and, to those who wish them,

I yield my kisses

“I am, by God, fit for High Positions” a poem by Wallada, daughter of al-Mustakfi - ruler of Cordoba (1023 - 1031/32)

translated by Nada Mourtada-Sabbah and Adrian Gully in their article of the same name on women’s political role in al-Andalus.

(via mariamagdaline)

67 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Everything declines after reaching perfection.

al-Rundi on the fall of Al-Andalus (via justuju)

164 notes

·

View notes

Photo

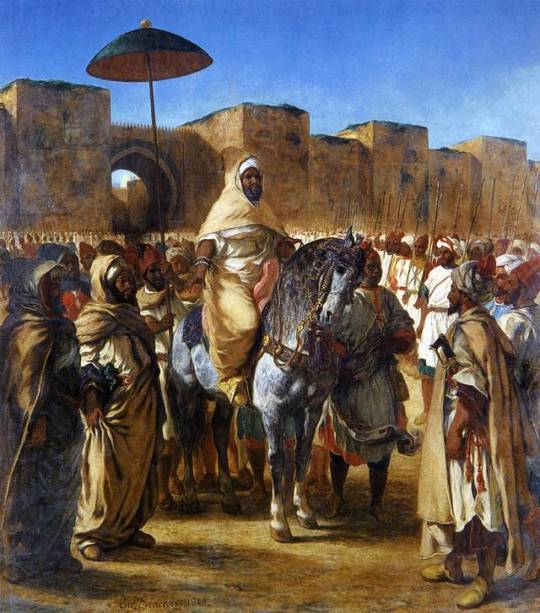

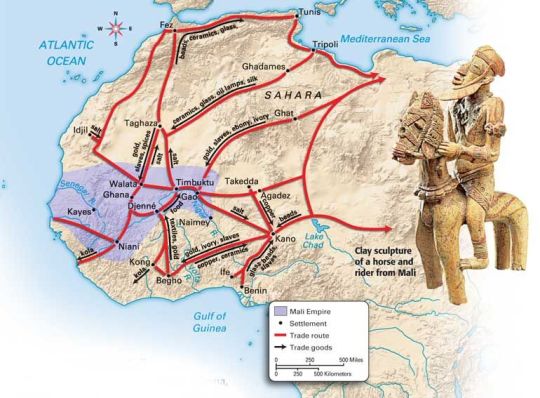

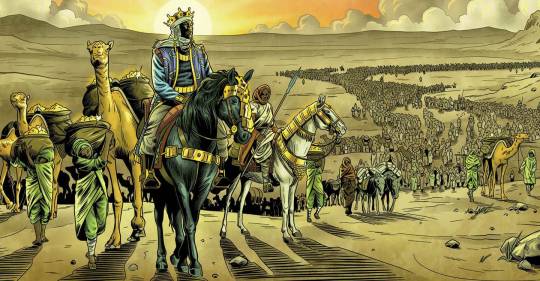

Moneybags Musa’s Wild and Crazy Pilgrimage!!!

Between the 13th and 16th centuries one of the wealthiest and most powerful empires in the world was the Mali Empire, located in what is now west Africa. It’s mighty army numbers over 100,000 at a time when France and England could barely muster an army over ten thousand. It ruled over millions of people. It’s capital, Timbuktu, served as a center of culture, wealth, and learning in Africa. Most importantly, because of it’s geographical location, the Mali Empire controlled an important network of trade routes between Europe, the Middle East, and sub-Saharan Africa, making the empire fabulously wealthy.

At it’s height, Mali was ruled by the powerful king Mansa Musa, who reigned from 1312 to 1337. Being the sovereign of a fabulously wealth empire meant of course that Musa himself was fabulously wealthy. In fact, he was so wealthy that he is often credited as the wealthiest man in history. It is extremely difficult to estimate how wealthy he was by modern standards, however most estimates claim around $400 billion US. By contrast Jeff Bezos’ net worth is around $118 billion. Whether this number is accurate or not, it is undeniable that Mansa Musa was seriously loaded.

Musa was a devout Muslim, and as such conducted a pilgrimage to Mecca in the years 1324-1325. When one usually thinks of a religious pilgrimage, especially in the Middle Ages, typically extreme hardship and sacrifice comes to mind. NOT FOR MONEYBAGS MUSA!. Musa made sure that on his pilgrimage to Mecca he would be traveling in style and luxury the likes of which the world had never seen. Making up his procession were 60,000 servants and slaves as well as hundreds of draft animals that carried all his “necessities”. Among his possessions was a large amount of gold. Each servant and slave carried around 1.8kg (4 lbs) of gold, while 80 camels carried around 23–136 kg (50–300 lb) of gold. Altogether he carried around 116,119 kg (256,000 lbs) of gold, worth around $5 billion US today.

Mansa Musa was very generous with his gold when his procession traveled across North Africa and the Middle East. Throughout every city, village, and town he would spend money like a drunken sailor, blowing money so fast that he would make the average US Congressman blush. He bought fine clothes, antiquities, fine foods, and other valuable collectibles. He would also donate large sums of money to local mosques, or commission the building of new mosques. He was extremely generous to the poor, donating to charitable organizations and surprising beggers and panhandlers with bags full of gold. Often, when parading through a city, he would have his servants toss gold coins to spectators. Mansa Musa’s wild pilgrimage would cement his legacy of wealth for centuries to come.

And he would completely devastate the economy of the Arabia and North Africa for the next decade. What Mansa Musa didn’t understand, in fact what few people understood at the time was the concept of inflation. The value of money is based upon it’s rarity. When more money is added to the money supply without an equal rise in the amount of goods and services, money losses value. If an extremely large amount of money enters the money supply very quickly a situation can occur called “hyperinflation”, where the economy is overwhelmed with too much money, making money itself almost worthless.

When Mansa Musa made his return trip to his empire he noticed that cities which were once thriving economies had been devastated by severe economic depression and had become bastions of poverty. What had happened? As it turns out due to Mansa Musa’s extreme generosity with his gold, he had flooded the local economy with so much gold that gold itself had become worthless. The consequences were dire. People saw their life savings made worthless overnight. Businesses and trade collapsed. The local populace had regressed from societies of complex trade to primitive barter. Unemployment, poverty, and homelessness reached epic levels while crime skyrocketed. Mansa Musa had made a big mistake.

Musa tried to fix the situation by selling back the items that he had purchased and taking large, high interest loans from moneylenders in order to contract the money supply. However the damage had been done, and many of the lands he visited would be gripped by economic depression for the next decade.

3K notes

·

View notes

Photo

ALGERIA. Timiaouine. Tuaregs from Mali fleeing drought. March 1974.

Raymond Depardon.

563 notes

·

View notes