Video

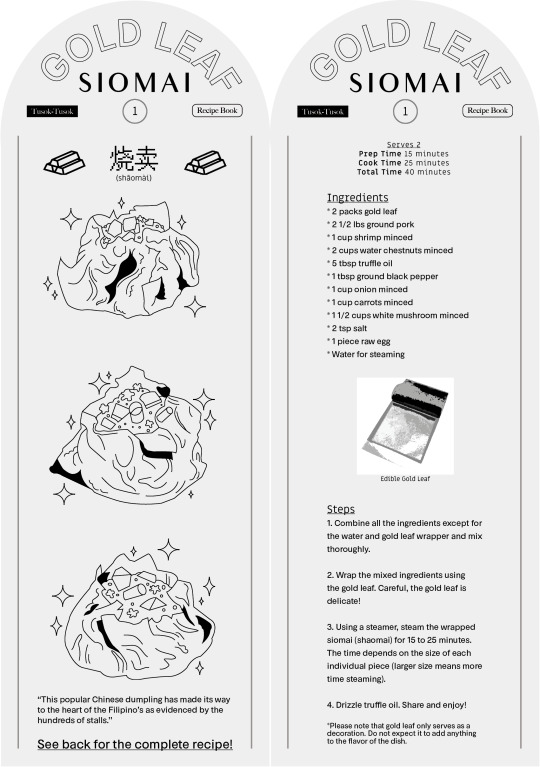

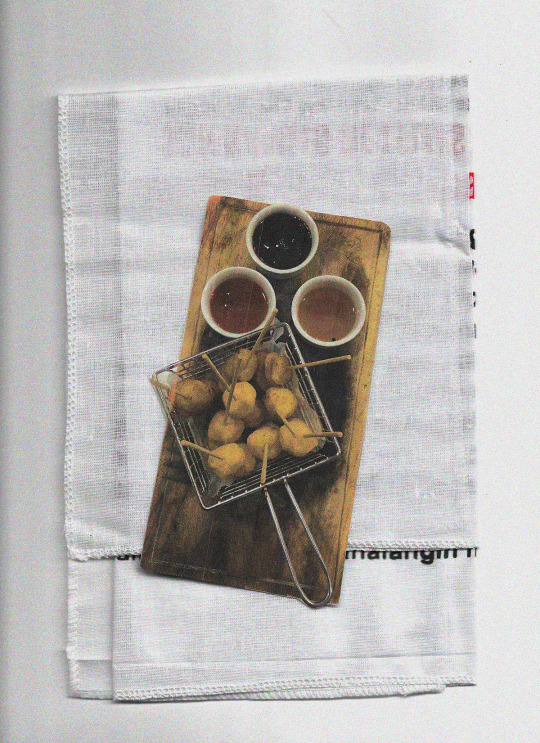

Episode 3 time! ⏰ We're taking the deep dive into the history and different versions of our favorite university meal, siomai.

0 notes

Video

It's Episode 2! Meet the people who run an irreplacable part of our neighborhoods.

0 notes

Video

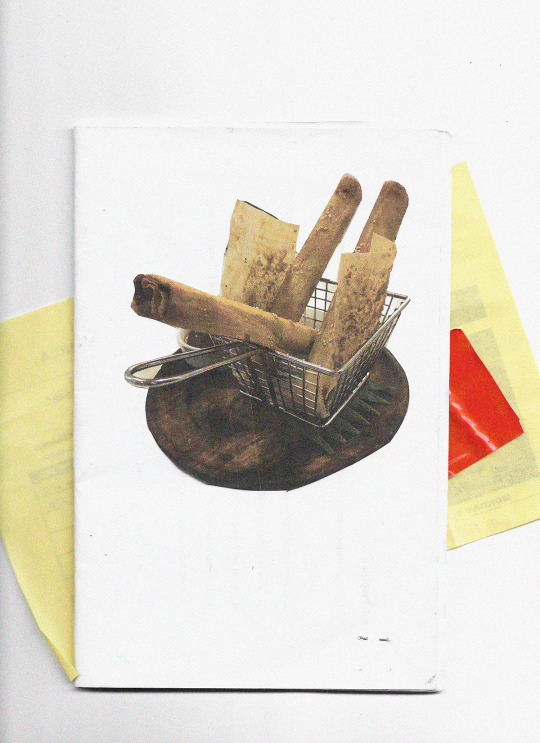

Here it is! Episode 1 of our new short documentary series on Filipino street food. We'll be taking a closer look into squidballs! See you next episode. 🤩

0 notes

Text

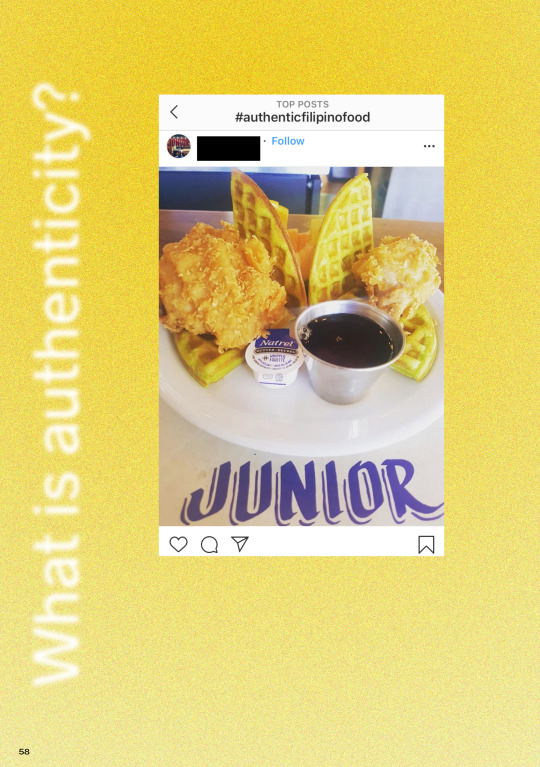

What is authenticity?

We are constantly on the search for “authentic” food... whatever that means. And that’s just the thing, what exactly does authenticity mean? What kinds of standards are we searching for?

Authenticity has one major philosophy: simplicity. With simplicity, there is the image of food that lacks pretentiousness and all the other bells and whistles that are so prominent in high-concept, high-price restaurants. There is a belief in the simplicity of the people who participate in the food’s commodity chain, and the processes within it: simple non-industrial harvesting, simple cooking methods, simple modes of preparation. Simple food plays into the mythology of having a meal free of commercial, profit-oriented interests, and instead, having it be associated instead with sincere workers. A classic example of this is upscale farm-to-table restaurants, that make generous usage of the words “grass fed”, “old fashioned”, or “greenmarket” on their menus.

The word “authentic” in the context of Filipino cuisine seems to imply things that aren’t necessarily in the realm of vegan buzzwords. Often, we judge a food’s authenticity based on its experience and maybe even its venue (where we eat it and in what manner). For example, authentic adobo is the adobo recipe our lola cooks, and everything else is just a deviation from it or a mere imitation. Of course, these “imitations” can be delicious, but they are not the adobo we recognize as the adobo. Another example is the quintessential Filipino version of spaghetti, sweet, with chopped up red hotdogs in it. And when someone asks specifically for authentic Filipino spaghetti, we point them to the nearest Jollibee.

But it’s an extremely puritanical way of thinking, to assign the label of authentic over certain dishes or sub-cuisines. Maybe the label is helpful for context, but definitely not for validation. Our household adobo recipes aren’t universal – in fact, every family has their own adobo recipe. Filipino cuisine is special in the way it lends itself to a lot of experimentation, inclusion or exclusion of ingredients, based on the personal taste of the diner. There is no canon way of cooking a specific dish, even when the dish is steeped in family traditions. And on the example of Filipino spaghetti, we don’t see any Italians up in arms about “bastardizing” their bolognese.

I had also interviewed some people, asking them to describe Filipino street food in a few adjectives. Many of them used the word “authentic”. I further prodded, asking what authentic street food would look like. More often than not, the average response the the question was, the kind sold on the street by vendors and peddlers in carts. But any change from its context automatically made it inauthentic.

This almost seems like common sense. Of course the authentic street food would obviously be the kind sold on the street – anybody would be able to come to that conclusion. However, there is the subtle implication that this so-called authenticity in street food must, at any cost, resist any kind of change or development, lest it lose its figurative “authentic” badge of honor. When we start viewing the foodways (referring to the intersection of food in culture, traditions, and history) of the working class as something that is authentic, even picturesque and a representation of how street food should be, well… it runs the great risk of fetishization.

The blame shouldn’t be directed to the people I interviewed who equated authenticity with the current state of street food vendors and businesses, though. This is said with full seriousness: it’s the fault of the system! Filipino street food, despite its lack of proper support or tolerance from the government, has been regurgitated into a marketing scheme to attract tourists (primarily white tourists) to come taste our weird grilled chicken intestines and grotesque developing duck embryos – all in the name of exoticism! And this, at the end of the day, is advertised to be one of the primary authentic experiences one can have in the realm of Filipino cuisine.

But exoticism is much more loaded with things to unpack. Exoticness is something both desired and feared, but must always be understood as standing in opposition (May 1996). Prerequisites to exotic food seem to be qualities of unusualness and excitement. Unusualness is apparent in gourmet food writing, where food writers introduce obscure ingredients or dishes, framing this as a way of democratizing gastronomy, and broadening the definition of “good food”. But what makes food “unusual” in the first place is usually its link to foreign (in terms of ethnicity, race, and even class) non-white people and places. These people and places are both geographically and socially distant from the writer, and this re-introduction of unusual food merely provides a superficial image of the culture to which it belongs to, designated for the use and pleasure of the food adventurer. This way of eating is dangerous – it substitutes the authentic relations and connections we can have with food with the “quick fix” of exoticness, giving colonialism a friendly and more liberal looking face.

The issue with exotic food, or maybe this is its genius, is that it suggests the radical democratization of food, claiming that all food is equal and that the food world is borderless, but the fact that these exotic foods valued mainly for their foreignness inherently does nothing to demolish standards of differentiation or hierarchy. It does this while still avoiding offending these democratic sensibilities by steering clear of traditional snobbery and elitism.

So, authenticity is overrated. Cuisine lends itself to innovation, and nobody can change or ignore that; we cannot pin down a certain dish at a certain place and time and call it the authentic version over everything else. Food production and enjoyment are inevitably linked to political, economic, and cultural flux. The late, great Anthony Bourdain even said, there is nothing more political than food because what dictates who eats what, or more importantly, who can and cannot eat, is politics. The economy dictates what resources are made available, and to whom. And lastly, culture takes care of our tastes, what we like to eat.

Doreen Fernandez, a teacher and cultural historian who wrote extensively about Filipino cuisine wrote some time ago, “To be considered Filipino, culinary practices did not need to be Filipino by origin. Nor did they need to preserve some original or authentic form… The question is not ‘What is Filipino food?’ but ‘How does food become Filipino?’”

References:

Fernandez, Doreen G. “Culture Ingested: Notes on the Indigenization of Philippine Food.” Philippine Studies, vol. 36, no. 2, 1988, pp. 219–232. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/42633085.

0 notes

Text

Kung wala kayo, edi wala rin kami

An interview on the state of vendors in UP Diliman

I interviewed Ate Edna Sinoy at Balay Kalinaw in UP Diliman on April 10, 2019, catching her right before an Alliance of Concerned Teachers Partylist event. She had just walked up from the bodega-turned-office of Samahan ng Manininda ng UP Campus (or SMUPC for short) in Pook Palaris, a small village within the UP Diliman Campus.

As we stood outside on the balcony, we talked about the state of the vendor’s livelihoods within the campus, especially on how the changes and modernization schemes enacted by the UP administration are being felt by them. But despite many threatening policies, they continue to fight the good fight.

Tusok Tusok: Ano ang iyong pangalan at posisyon sa SMUPC?

Edna Sinoy: Ako po si Edna Sinoy, tagapangulo ng Samahan ng Manininda sa UP Campus.

TT: Ano ang prinsipal na misyon o layunin ng SMUPC?

ES: Ang layunin ng Samahan ng Manininda ay makapagserve sa mga estudyante, tapos ‘yung mga kawani, at sa lahat ng mga tao na dumadaan dito sa UP, diba. Atsaka siyempre, para magkaroon ng kabuhayan ang mga bawat pamilya, ang bawat kasapi, para matugunan ang mga pangangailangan ng aming mga pamilya. Sa pag-aaral din ng mga anak namin.

TT: Ano ang mga pinaka importante at urgent na mga isyu na hinaharap ng mga manininda sa UP ngayon?

ES: Sa ngayon, lingid sa mga estudyante na maraming pagbabago dito sa loob ng UP. Nandiyan na ‘yung pagpapatayo ng mga bagong mga gusali, tapos kaakibat niyan ay ang pagkakaroon din ng mga negosyo na sa loob ng UP. Nakaplano na ‘yung pagtatayo ng mga food hub, kung saan, ang mga manininda ay gusto na nila na ilagay sa isang lugar. Sa tingin namin, hindi na ‘yun makakatulong sa mga estudyante. Sa ngayon, nakakalat ang mga manininda para ‘yung mga estudyante na bago pumasok sa eskwela, may madadaanan silang manininda. Pwede silang bumili, habang naglalakad, kumakain sila. Kung sa food hub kasi, sasadyain pa nila ang mga lugar. Atsaka siyempre, iba na ang mga presyo ‘nun – posibleng tumaas ang mga bilihin, at sa renta pa lang, ang mahal na.

TT: Sa anong mga paraan kayo nagrerespond sa mga isyung ito?

ES: Madalas kami nagmimiting. Humihingi kami ng tulong sa mga organisasyon ng mga estudyante, mga organisasyon ng mga kaguroan, ng mga kawani. So, salamat, kasi nakakatulong talaga sila. Ang SMUPC ay hindi lang naman dito sa UP para kumita… Kami, bilang organisasyon, hindi ito ‘yung ordinaryong organisasyon lang na kanya-kanya. Ang ginagawa kasi ng samahan ay inaalagahan din ang kapakanan ng bawat kasapi, no. Ganun din sa mga estudyante. May mga iskolar kami – marami na kaming napagradweyt. Tatlo na ‘yung napagradweyt namin na iskolar na UP student… Ang Samahan, hindi siya ‘yung samahan lang na para makatinda lang. Hindi, kasama kami tumutulong din sa mga kapwa naming ibang organisasyon sa loob ng UP campus. Ang mga members namin ay binibigyan ng Samaha ng benepisyo: SSS, Philhealth, insurance. Katulad nga kay Amor*. Dahil inaalagahan talaga ang organisasyon ang bawat kasapi, may maiiwanan siyang pondo para sa mga anak niya. Enrolled kasi lahat ng members sa SunLife Insurance. Sa group insurance namin, makakaavail si Amor ng PHP140,000. Tapos, dahil kinuha namin siya bilang PRO, nadagdagan ito ng PHP250,000. Kaya sinisikap namin na mapaayos ang organisasyon, kasi gusto din po namin na hindi lang ito pang kabuhayan, kung hindi parang pamilya na kami. Nagkakaroon ng mga pagpapala ang Samahan, so inaambag namin ito sa mga alam naming nangagailangan – mga estudyante, mga empleyado, o mamamayan dito sa UP. Nagbibigay din kami ng support pag may mga trahedya. ‘Yun ang nakakalungkot kasi ang tingin nila, dahil maliliit lang kami ituring, kasi mga kariton-kariton lang, di lang nila alam na maraming nagagawa ang Samahan.

TT: Nasabi niyo na po kanina, may student hub na itatayo sa UP. May mas specific examples ba kayo kung paano maaapektuhan ang mga manininda?

ES: Malaki ang epekyo niyan. Marami na magtitinda dito sa loob. So, imbis na saamin nabibili, edi siyempre, lalo na pag may mga bago, pupunta sila doon. Alam mo naman ang mga estudyante, mahilig sila pag may mga bago. Pero ganoon pa man, hindi kami nawawalan ng pag-asa. Kasi ang mga estudyante naman, sisikapin namin na makapag-serve kami ng mas mura. Plano namin magkaroon ng mga survey, kung ano ‘yung mga gusto nilang mga pwedeng kainin. Hindi nagtatapos ‘dun sa mga puro fishbol, mga canton-canton lang, diba? Pero may mga plano na kami na baguhin ‘yan, dagdagan ng mga mas nutritious.** Sana ma katuwang namin ang mga estudyante para ihapag sa UP Admin na payagan na makapagbenta din ng ibang mga uri ng pagkain.

TT: ‘Yung student hub, may private [concessionaires] na papasok?

ES: Ino-offer na nila sa mga private concessionaires. Kung mapapansin mo, may 7/11. Dito, magkakaroon na ng mga Starbucks.

TT: May chismis na kumakalat na Ayala-funded daw ang student hub na ‘to.

ES: Opo! Kawawa. Atsaka, kung ‘ganun na, hindi na mura ang xerox, diba? So, ang epekto ay babalik din sa mga estudyante.

TT: Anong klaseng suporta ang binibigay ng UP Admin para sa mga manininda?

ES: Ang support ay depende sa umuupo. Meron diyan na negotiable lagi. Hinahamon pa nga kami ng all-out war, kasi tingin sa amin maliliit. Pero hindi kami nagpapatigil, na patuloy kami na nagkakaisa. Nilalaban ang mga karapatan namin, lalo na pag may suporta ng mga estudyante. Hindi naman nawawala ‘yon. Sobrang lumalakas loob namin. Nagpapasalamat din kami sa mga estudyante, kasi kinikilala nila ‘yung mga tulong at serbisyo na binibigay ng Samahan.

TT: So hindi sapat ang suporta ng UP Admin?

ES: Oo! Kasi katulad niyan, paaalisin kami nang wala naman kaming relokasyon, diba? Hindi muna nila inayos ‘yung may paglilipatan, tapos saka nalang pag nandiyan ang mga proyekto nila.

TT: Ano ang mga pinaka mahalagang pagbabago o reporma na gusto niyong makita na magbibigay ng mas madaming oportunidad o mas matatag na seguridad sa trabaho sa mga manininda?

ES: Sana kilalanin ng UP Admin ‘yung ginagawang serbisyo ng Samahan, ng mga manininda. Lingid sa kaalaman nila, ang manininda kasi, nasa guidelines naman ‘yan na mula 6 ng umaga hanggang 10 ng gabi, kami talaga ay hinihintay namin ang mga estudyante bago kami umuwi. Alam po namin na wala na silang makakainan. Tapos, sa manininda nakakautang ang mga estudyante. Pero sa mga private concessionaires hindi. Kahit hindi kami nababayaran, kahit gradweyt na sila, bale wala sa amin ‘yun. Mahalaga makatulong kami sa kanila. Mas maraming bumabalik at nagpapasalamat. Marami ngang gumagradweyt at ‘dun mismo habang nagmamartsa siya, nagpapasalamat siya sa mga manininda kasi kung wala daw kami, maaaring ‘di siya nakapasa sa exam kasi gutom na gutom siya. So, ayun, sobrang nakakataba ng puso ng mga manininda. Inspired kami na magtinda araw-araw, kasi turingan ng mga estudyante at manininda ay parang pamilya na. Marami sa amin, parang anak-anak na ‘yung mga estudyante. Tapos kunwari, bakasyon, tapos wala silang pamasahe, sa amin sila nakikitira kasi sarado na ang mga dorms. So ‘yun yung ‘di alam ng UP Admin. Sinasabi nila na hindi kami nakakatulong sa mga estudyante, pero kabaligtaran ‘yun. Basta bukas kami, kunwari pag may mga activity, humihingi sila ng support, kami naman dahil may mga suppliers kami, tumutulong kami. Kung wala kayo, edi wala din kami. Sana, ‘wag kayo magsawa.

* Amuris Bacaran, better known as Ate Amor, was a well-loved vendor who sold turon, banana-cue, and the like by the College of Social Sciences and Philosophy (one of the busiest buildings in the campus). While still continuing to work, she had been suffering from coronary heart disease and heart enlargement, and recently passed away late March of this year. May she rest in power.

** According Ate Edna, the policies enforced by the UP Administration only allow vendors to sell food like kwek-kwek, squidballs, pancit canton, hotdogs, biscuits, and other mostly instant and non-nutritious meals. There has been a long-standing clamor from both students and vendors for them to be allowed to sell more substantial food, such as rice meals.

0 notes

Text

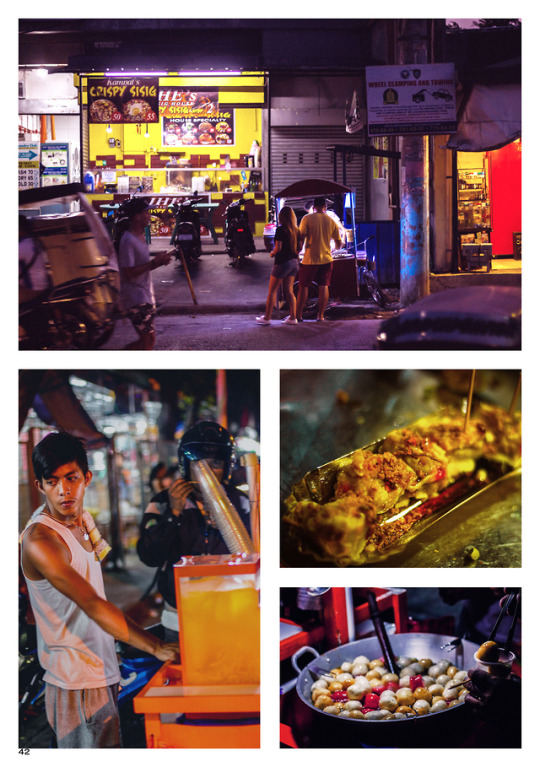

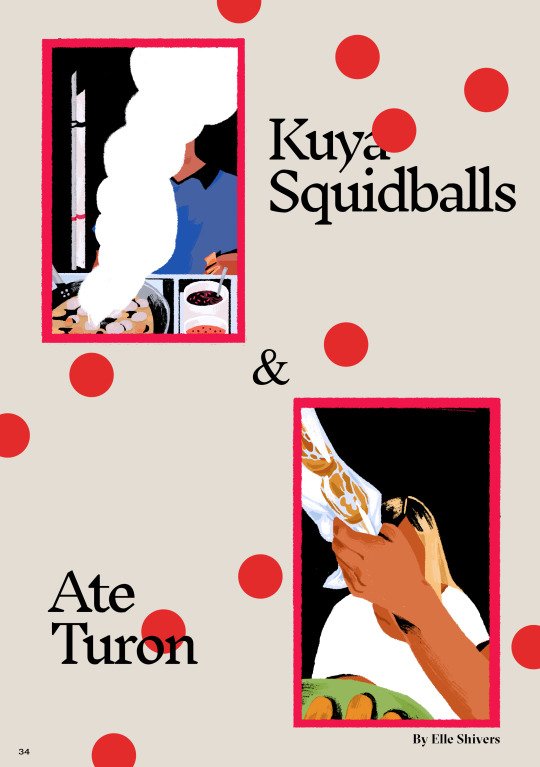

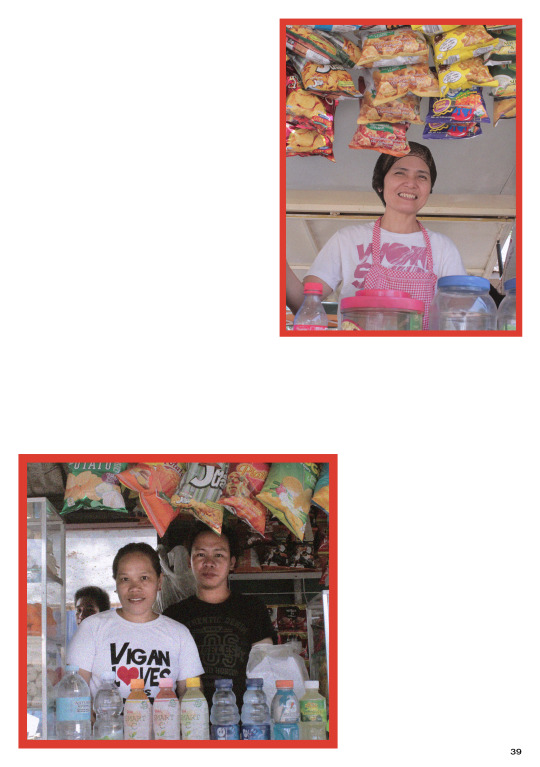

Kuya Squidballs & Ate Turon

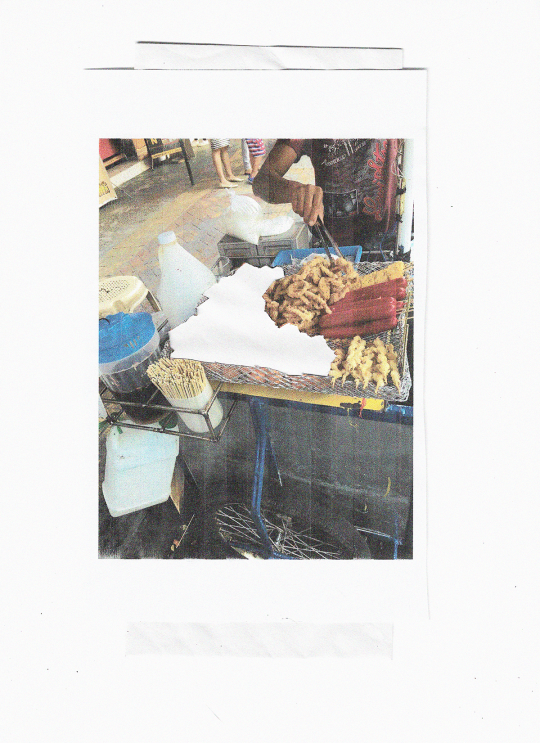

Enjoying and appreciating culinary efforts isn’t only limited to just sit-down restaurants, where the chef is often hidden in the kitchen. The maninindas, or street food vendors and peddlers, though they admittedly aren’t the kinds of people that first come to mind, also play a part in the culinary realm.

Just like running a restaurant, a cafe, or a bar, running a small street food business is no walk in the park. It also involves keeping track of inventories, going to the market, meeting a quota, and getting up early the next morning to do it all over again. And when all is said and done, Ate and Kuya undeniably serve food that we look forward to, that we crave.

And it really isn’t a walk in the park, to run this kind of business. The reality is, street food stalls or carts aren’t really “formal” businesses. So, no “employee” benefits, no paid leave, and definitely no safety net. Majority of the Filipino population is below the poverty line, and these people are potentially the main buyers and sellers of street food. A street food operation is a small, day-to-day, person-to-person, cash-based operation that requires no formal education; it has found its niche in developing countries like the Philippines. And it’s a vicious cycle – because of long standing poor economic conditions, the proliferation of street food is necessitated.

Food is not only about the product, but also about the people behind them. In this section, the people we’ll be talking to and about aren’t trained chefs, nor are they often-featured restaurant owners. We sometimes don’t even know their names, but we might refer to them as something like Kuya Squidballs or Ate Turon.

So, I asked them, what do you think the significance of being a manininda is?

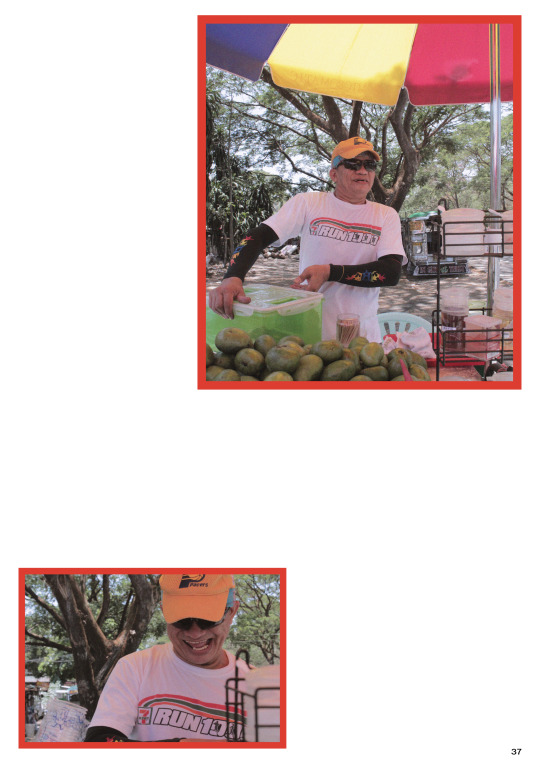

Kuya Nare

Ang kahalagahan ng trabaho bilang manininda ay unang-una, nagbibigay kami ng serbisyo sa community, sa mga kaguruan, at sa mga iba pang sektor na nangangailangan ng aming serbisyo. Sa pamamamagitan ng mga pangmasang itinitinda namin, nabibigay namin ‘yung serbisyo na para sa mga taga-community at sa mga Iskolar ng Bayan.

Kuya Francis

Marami na akong napasaya, pabalik-balik sila dito. Pag wala ako, nagagalit sila! Haha!

Ate Jane

Malaki ang kahalagahan ng trabaho ko. Napa-aral ko nang mabuti ang mga anak ko. Nagtapos sila. ‘Yung isa, sa Miriam College. Tapos, ‘yung isa naman, sa PUP. Kaya malaking kahalagahan ang pagtitinda para sa akin.

Ate Avi

Nakakapag-bigay kami ng serbisyo sa mga estudyante, at sa mga empleyado ng unibersidad!

Ate Dylene & Kuya Jess

Para makakain po! Haha. Ito po ang kabuhayan namin.

0 notes

Text

Foie gras taho and the appropriation of poor food

There was this fine restaurant in Bonifacio Global City (now closed) that served a thing called foie gras taho as part of their multi-course set menu. Its description of ingredients, which I quote from a screenshot I took of their now-defunct website, reads: “Steamed foie gras custard, sherry syrup, tapioca, green apple, miso, mushroom, chives”.

And to add to that, the name of the dish itself is “Inadequacy & Retaliation”, comparing the transformation of taho into something gourmet with Rizal’s assimilation into European society. This is how it was further described on the website by the chef (italics were added for emphasis): “This journey from [Rizal’s] inadequacy to empowerment inspired me to transform something so simple, almost poor into something decadent and worthy of international merit drawing a juxtaposed inspiration from both our hero’s journey in Spain and the reinvention of our local street dish into something more inspiring”.

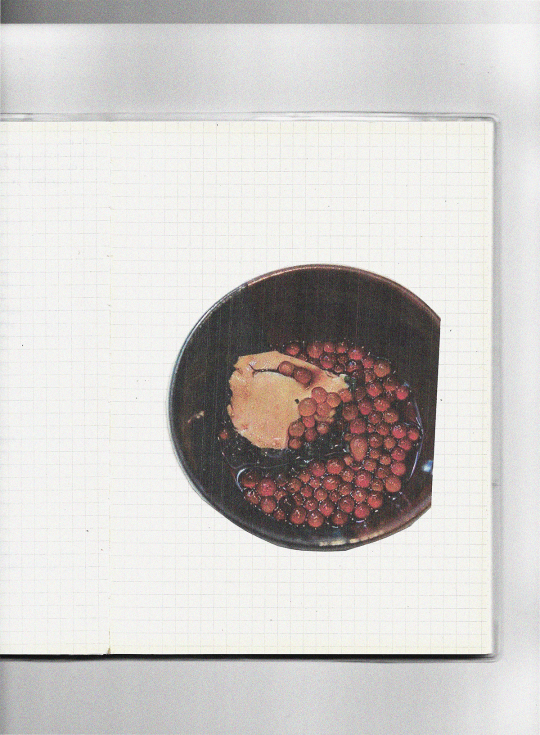

The thing is, this doesn’t even sound like taho anymore. Taho is probably one of the simplest of Filipino street foods – the traditional type consists of three main ingredients: sago pearls (or tapioca balls), arnibal, and silken tofu. There are flavored types of taho, for example, strawberry taho is especially popular in Baguio because the fruits grow abundantly in the cooler climate of the mountains. But gourmet taho or not, this hardly sounds like the thing it’s trying to “improve” on in the first place. From the description alone, it seems to be inclined to more savory flavors, which would make it virtually indistinguishable from “normal” taho, which we all recognize as being sweet, even sometimes sickeningly sweet.

But its unrecognizability as the taho this dish is trying to be isn’t even the main aspect that makes it problematic and conceptually iffy. We have to pay attention to the wording, the adjectives used to describe the two tahos that were made to be two contrasting entities: the taho that was in need of elevation and improvement, and the gourmet, foie gras taho. The former was described as being “poor”, “inadequate”, and lacking in inspiration. On the other hand, the reinvented taho was, well, everything but that – it’s the antithesis of everything poor taho stands for.

Does poor taho need retaliation, though? Have there been groups of diners and chefs calling for the rejection of street foods, in favor of more elevated versions worthy of “international acclaim”? Or is taho some sort of dying, endangered dish that needs revitalizing to bring it back into the attention of Filipino diners via presentation through a fine dining lens? Of course, none of these are even remotely true. If so, the most important question that needs to be asked is: is making taho “more inspiring” just an easy euphemism for making it more in line with the tastes of the rich and the more cultured, AKA, the ones who don’t consider street food to be in their vernacular diet? Arguably, taho and other types of street food are already inspiring enough – they have survived decades, if not centuries, feeding masses of everyday, working Filipinos.

Of course, chefs are much like artists; their main goal at the end of the day is, or at least should be, innovation. After all, on the other hand, it would be downright lazy and a fraud for a formally trained chef to serve the exact kind of thing you’d see being sold on the street, with little to no reimagining or transformation, for a much, much higher price. But, unfortunately (or fortunately), whether in food or in art, our actions have implications, and they are rooted in ideology. To put it simply, it seems that these dishes can only be considered worthy of culinary attention and acclaim when they are cooked with expensive ingredients and served in very controlled, civilized spaces. In the appropriation of the concept of taho, and fine, maybe even the image of it, it fails completely in not only representing it accurately and respectfully. But most importantly it fails in making no comment on why exactly they think that Filipino street food is uninspired, boring, and “poor”. But I think we can hopefully figure out why. (Hint: it’s classism.)

This appropriation of poor food into spaces like fine dining restaurants, expensive buffets, or fancy hotel lobby cafes isn’t a niche phenomenon. In fact, it’s indicative of a larger phenomenon sociologists and anthropologists have penned the “Omnivorous Theory”. Cultural omnivorousness describes the marker of “high status as signaled by selectively drawing from multiple cultural forms from across the cultural hierarchy”; it is defined by a breadth of taste and cultural consumption (Johnston & Baumann 2007). In other words, relying on what has been traditionally considered as highbrow (French food, fine dining, the like) is now ineffective or passe as a way of exercising elite-ness – the elite now turn to exploring their freedom to dabble and appropriate cultures that have been not traditionally seen as “high” from different ethnic and class cultures. With the Omnivorous Theory in place, we can recognize that the co-option and appropriation of food across social classes, particularly from the bottom up, is one of its main manifestations.

Parallel phenomena like our foie gras taho is observable everywhere. For example, fishermen have their own sub-cuisine, which is part of the larger culture which they are a part of. Often, a “gourmetship” is developed based on the smaller and less profitable products of their catch, and the result may taste superior than the “good” products, in turn commanding a higher price once it has been popularized and co-opted by those who want “in”. The San Francisco cioppino is an actual example of this. Another prime example is soul food. Food like collard greens, chitterlings (pig intestines), barbecued pork, and sweet potato pie were once the old-time food of the rural and impoverished American south, ergo, the food and symbol of the Black Power movement in the 1960s and 1970s. However, soul food eventually became the food of the African American elite, and when white elites tried it, they loved it. Black Power activists then sought to reevaluate the symbols of African American culture, as soul food took on great prestige and began to be served in the best restaurants, and not just African American ones (despite racism being a continuously lasting and powerful force). The leafy couve tronchuda in Portugal was once considered the food of the poor, but it has been revalued as a “nostalgic ethnic marker”; it is now a key ingredient in many Portuguese soups, and is found virtually in every gourmet restaurant in the country. Polenta has origins as “poor food” too, but it is not on gourmet menus in Italy, and is recognized globally as a hallmark of Italian food (Anderson 2005).

In the Philippines, having an extremely rich food culture that varies from region to region, and a very powerful middle class, this is very apparent currently in the local food scene, especially in urban areas. The Filipino working class also has valuable food systems that are critical in their lives (such as street food, the carinderia, et cetera). As mentioned earlier, street food is beginning to find a new and odd place in upscale Filipino restaurants, with it being framed as a “nostalgia food” or a taste of authentic Filipino-ness. They are served in a way that values aesthetic presentation, perfectly and deliberately arranged. It’s even consistently featured in international food festivals in business districts, in Makati or Bonifacio Global City.

Now, nobody is saying that eating is a no-fun-allowed zone, where reinvention and experimentation with food is forbidden. The point isn’t to say that food is static, and that it must belong to a certain group of people eternally, safeguarded so no “outsiders” can access it. Like language, cuisine grows and develops through the exchange or borrowing of ideas; there is no such thing as “purity”. It is defined by change. However, and this is a big however, this inevitability of change does not include an inevitability of misappropriation, of subscribing to a I-follow-no-rules approach. It’s… a lot to unpack, but it’s important that we try to, anyways. Just because food and cooking are things that makes us feel good, doesn’t mean that they are exempted from being distasteful or problematic in terms of concept or how its served. It’s just like art in a sense; a beautiful and expertly-made painting doesn’t mean it’s immune from criticism just from how amazing its outward appearance seems to be. We must be critical and discerning towards the intent behind what we eat, its social implications, its tone, and what kind of narrative it wishes to push about the people and culture that it “borrows” from. Again, nobody is outright banning you to eat any other incarnations of the foie gras taho if you really want to experience it. But we cannot be amnesiacs and selectively blind when it comes to being mindful that in appropriating “poor” food into “rich” contexts, no useful or insightful commentary is being made. There is no innovation in commandeering the aesthetics of the working class, while simultaneously treating them with disdain and patronization.

References:

Anderson, E.N. Everyone Eats: Understanding Food And Culture. New York University Press, 2005, pp. 110; 124-129; 136-139.

Johnston, Josée, and Shyon Baumann. “Democracy versus Distinction: A Study of Omnivorousness in Gourmet Food Writing.” American Journal of Sociology, vol. 113, no. 1, 2007, pp. 165–204.

0 notes

Text

In the shadow of the city

What is a city without the end goal of modernization in the name of convenience, better mobility, and general comfort in living? There is no such thing as empty space here: even the promised “green spaces” of Bonifacio Global City were eventually transformed into ground zero for office buildings and retail and dining outlets. As each year passes, the spaces we occupy seem more and more claustrophobic, and like every wall is on the verge of collapsing with how much we’re trying to squeeze in.

To some of us, the word “modernization” might sound like music to our ears – modernization of our public transport system, of our industries and infrastructure, of our thoughts. We often talk about how great it would be to decongest Metro Manila and start building cities and other urban centers in provincial areas. And in the city proper, where we’re situated, “modernization” has become a synonym for getting rid of the ugly parts of urban living. Case in point: the jeepney modernization scheme, which called for the phasing-out of jeeps which were at least fifteen years old and replacing them with more environmentally-friendly units. Of course, nobody is trying to refute that the public transportation system in the Philippines leaves much to be desired in terms of comfort, speed, and convenience (and that in itself is an extreme understatement), and that we should collectively – unquestionably – take steps to lower our carbon footprints. However, with the rapid, instantaneous, and drastic modernization we aspire for and want so badly, many Filipinos are left behind with no safety net, their livelihoods and families unaccounted for.

No matter how progressive we think any kind of modernization is, it will never truly be forward-thinking if it does not carry us all into a easier to navigate, more livable urban life. This is a simple fact: when we try to squeeze more things into a limited, inevitably whatever that doesn’t fit gets shoved out.

But let’s shift our focus a little bit and talk about how this affects food systems. Street food provides an irreplaceable source of inexpensive ready-to-eat food for workers of every class (most especially those of the lower classes) and occupation. It is an especially important part of the commuter’s day to day life. To the women and men who produce, make, and sell ready-to-eat food on the street, the microenterprise that the street food business provides significant income for themselves and their families. These public kitchens have helped feed an innumerable amount of Filipinos and have proven significant in the local economy: in 2010 the World bank estimated that 40% of the Philippines’ Gross Domestic Product comes from the underground economy, which street food is counted as a part of.. Generally, the number of street vendors increases with modernization as traditions of eating at home break down in the face of urban sprawl, transportation congestion, and the general instability of living in Manila. In spite of this, policies of both governments and international agencies sought to eradicate the sector. The food itself has been condemned as unsanitary, the vendors as a nuisance (they are a target of harassment during street clearings), and in general the industry as something that stands in the way of a “beautiful” and “modernized” city. According to a study on street food in the Philippines, “The precariousness of the trade stems from its very nature. Food must be prepared and sold daily. Skill is necessary for determining the amount to cook and the place to market. Illness of the vendor or her family members can mean the suspension of selling, which implies losing customers, profits, and even the space where they sell.”

On the topic of modernization again – rapid economic transformation generally results in a greater disparity of incomes. And so, the potential for conflict between government and vendors only increases with congestion. This leaves us with the difficult question: how do we modernize our cities but still leave space for the traditional, small, informal enterprises such as street food?

In every city, wherever we step foot in Metro Manila there are all kinds of malls, all kinds of commercial spaces that promise a life of entertainment, leisure, or even urban beautification. And within these commercial establishments is a continuously growing number of food choices – in the larger malls owned by major developers most of these are franchises brought from abroad, marketed towards a middle-class and upper middle-class market (think Shake Shack, Red Lobster, Denny’s, Popeye’s, and others). Arguably, we can see that the most developed parts of our cities are in favor of the interests of more privileged and mobile classes – the ones who have a choice and obviously would not choose to subsist on street food for most of their meals. And if we are to keep up this adrenaline-fueled, tunnel vision method of making Metro Manila “better”, what will happen in the next few decades? Yes, we will have state of the art entertainment centers, a world-class dining scene, and lively shopping destinations, but that version of modernity would only be skin deep! The darkest, dirtiest side streets of Manila would continue to never be illuminated, and will be forced to survive on less and less as time goes on. All in aid of the comfort and relief for a select few. Modernization cannot be mutually exclusive.

Despite their unquestionable and established role in the cities, many of these street food vendors and peddlers are continually pushed outwards into our peripheries and downwards into more economic anxiety. Because of this lack of support and cold shoulder turned towards them, these small businesses are left with no choice but to stay the way they are, defined most by what a lot of us dislike about them – unsanitary, disorganized, an eyesore. While it’s within our rights to demand a better quality of life, this shouldn’t only be defined by the number of restaurants from abroad are brought here, or by the multiplication of ultra-commercialized spaces (that aren’t even really accessible for the wider masses of people to enjoy and take part in). Better quality of life in an urban, modernized cityscape must be defined by better quality of life most noticeably in the most vulnerable sectors.

References:

Tinker, Irene. “Street Foods: Traditional Microenterprise in a Modernizing World.” International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society, vol. 16, no. 3, 2003, pp. 331–349. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/20020170.

0 notes

Text

On the dirty kitchen

Let’s start with the question: why is it looked down upon to eat with our hands? The answer is easy, and we’ve been told many times why. It’s dirty, it’s rude, it’s uncivilized. And we’ve internalized it; in general, I don’t think we would choose to permanently turn away our spoon, fork, and knife in this day and age. While there’s nothing wrong with that – swearing allegiance to a gesture as inconsequential as eating with your hands won’t make any of us better or more Filipino – we can see there had been a shift somewhere in history where we picked up utensils and never really put them down.

In this shift, there is divisiveness in not only what we eat, but maybe more importantly, how we eat it. This can best be seen in how our values as a nation have contorted and transformed (maybe even by force) in the context of the Philippine kitchen. More specifically, the public kitchen.

The kitchen represents something – something more than a space where we prepare our meals or where we gather for them. The kitchen we recognize in our homes now, one that it only complete with a refrigerator, a sink, a stovetop, and maybe even a microwave, plus other smaller appliances, is a product that’s been shaped by our history. It has been a space in our homes, now irreplaceable, that has undergone a great amount of change over the past century due to colonization and foreign influence, and by extension, on changing notions on sanitation and hygiene in the country.

In earlier times, while we were still under the power of Spain, forced labor in the fields was so widespread and brutal that Filipinos, indios, no longer had the capacity to prepare food in their own homes. It’s not like they had the resources to, anyways – every family and every worker was short on the food and personal property required to prepare a full, substantial meal. So what happened was that everyone started to pool what they had together and bring their meals out into the fields, turning essentially the whole process of not only food preparation, but also the act of eating, into a communal activity. (But it’s important to note that the idea of communal eating wasn’t a completely new idea. Feasts were a prominent feature of pre-colonial Filipino society.)

However, the privilege to partition the spaces they occupied for specific activities was only accorded to the upper classes. Cleanliness was sacred, it was a virtue, and was expressed spatially. Spanish eating habits, that is, eating with utensils and definitely not with the whole town, became a key method for cultural elaboration. In other words, it became a surefire way for the elite to boast and make known their status. In the context of food and eating, to be an elite in those times meant that the “rituals” and decorum you have at the dinner table must be aligned with European ideals of manners. And so, the people eating out in the fields as a community, because of their lack of “European manners”, their lack of cultural elaboration, lack of formality became synonymous with the unclean and the uncivilized. Unsurprisingly, because they were indios. But even in the aspect of eating, something that is common between all classes, ways were still found to further push them down.

This idea of “partitioning of space” only continued to be prominent when the Americans came in. The American occupation reinforced negative attitudes towards public eating, but in this case, they claimed to have the medical sciences on their side. A certain disgust was held against our humid, tiring climate; it became easy to conclude that all Filipinos were diseased, and assert that we needed to be “freed” from it. But of course, even the most powerful nations in the world cannot alter the climate or the ecology of a country. The only feasible way to “free the Filipinos from disease”, it turned out, was to crack down on our kitchens and our food. Professor in the Department of Filipino in Ateneo de Manila University Joseph T. Salazar writes,

Interestingly enough, the perceived dangers stemmed from the habits of the locals that many visiting Americans found highly irregular and unsanitary. Instead of looking at a number of environmental conditions that contributed to the breeding of disease, the cookbooks and materials circulated by health and sanitation departments often attributed the problem as the consequence of cultural depravity.

These became the one of the main sites through which the Americans attempted to construct a model for modernity. Through modernizing the kitchen, enforcing ideals of what is “healthy”, what is “now”. But of course the underlying ideology was to push Filipinos into being “civilized”. After all, healthy (civilized) individuals equaled a healthy (civilized) society. And the kitchen was the perfect target for this – it was small, but pervasive enough that every household would (should) have one.

By the end of the American occupation in the Philippines in the 1940s, white, consumerist American modernities – partitioned houses, gated communities – became commonplace. It became the goal. All decisions, not only in terms of food choices, were justified by a fundamental need to if not improve, maintain, one’s social standing.

The idea of physical space had become a source of a new kind of anxiety, especially for the non-elite. Both imagined and physical spaces for the public have now been scaled down and erased significantly. And even within private spaces, the personal confines of a house, there is the tangible, observable phenomenon that the partitioning of space is literally used as a means to divide people of different social standing. Philippine domestic architecture has now fully embraced and embodies the old residues of colonial and racial privilege in the design of the kitchen. The existence of the dirty kitchen has replicated old attitudes about privilege, and therefore separation of class, by making distinctions between what kind of work is believed to be “acceptable” in the immaculate, protected confines of the main kitchen.

What is there to be done in a dirty kitchen? Of course, all the dirty work. It’s where all the smelly and messy food preparation is done, all the frying, all the smoking. Meanwhile, the main kitchen remains pristine – the ripening fruits are displayed, the knives slotted in their correct spaces in the block, and the counters always newly wiped down, shiny. The dirty kitchen is always separate from the “main” house, blocked off by a wall or maybe even a different structure entirely. The structures of our kitchens can translate how we interact with each other and our immediate environments, using food, cooking, and eating as the medium.

But it is not only ideas of different kinds of work that are partitioned, but of course, within this is the partitioning of who does the work and what spaces they are allowed to occupy. Though it may be an uncomfortable topic (but absolutely a necessary one) for many middle to upper middle class Filipinos, we cannot deny that there are certain spaces within our households that our househelp can and cannot occupy or use. The dirty kitchen is a prime example of this – despite there being an arguably better kitchen with better appliances and layout, it is one of those spaces that only we can fully utilize. It’s also common that the househelp eat their meals in the dirty kitchen, unless the family of the household is unusually generous.

We still continue to hold onto a great, unshakable anxiety towards “dirtiness” within the spaces and concepts of food and eating – and this is completely normal when talking about concerns about health or diet. But more often than not, this anxiety towards “dirtiness” is also attributed to a certain kind of people, a certain kind of labor: one that is derived from our idea of lack of conduct or lack of understanding of formalities.

Being thrust into modernity, being forced to conform to Western ideals of civilization has left a lasting scar on how we treat not only each other, but more importantly, how we treat the people who do not have as much as us. Until we decide that now is the time to figure out how to let go of partitioning (both literally, and figuratively) the spaces we occupy based on class and the types labor intertwined with it, we will never truly find an end to being a bitter, vicious cocktail of both complacency and uneasiness.

References:

Salazar, Joseph T. “Eating out: Reconstituting the Philippines’ Public Kitchens.” Thesis Eleven, vol. 112, no. 1, Oct. 2012, pp. 133–146, doi:10.1177/0725513612452654.

0 notes

Text

A different kind of food magazine

The food magazine – it’s not the usual lens through in which we consider issues of class. If anything, the conventional publications about food and dining are virtually apolitical. After all, what exactly is there politicize in glossy, touched up pictures of food?

The food magazines we pick up at groceries, at bookstores, or in waiting rooms are probably one of the easiest distractions we can get to avoid the stress of our already political lived realities. Food is a staple in our lives because we are living beings, and we aren’t given much choice on the matter. But good food is comfort, a form of escapism even, something to imagine fondly much like one imagines a romance. This is the kind of passionate imagery food magazines aim to project in our minds: imagery that leans towards detachment from everything that isn’t the divine and the indulgent. Now, let me dream of this delicious thing I saw on page 35 that I’ll probably never get around to making.

But wait – before you’re completely convinced – there’s of course the argument that of course we can examine the hierarchical nature of our society using food as a medium. More specifically, the food magazine. Through escapism, a more pleasurable, more opulent world is promised. Thus, the idea of food porn. From the most carefully edited food magazines, to even the free-for-all essence of microblogging, especially on Instagram, the idea of food porn has been made so pervasive that even our titas are slapping the hashtag onto their latest post. It’s a buzzword, a surefire headline to even the most overdone article. And what is pornography, be it for food or humans, but a manifestation of escapism and self-indulgence? And to stretch the logic, what is pornography, especially the human kind, but a reproduction of the hierarchy between the man and woman, the masculine and feminine, the empowered and disempowered?

Jumping off of that last point, Alan Madison – a producer and director of high-budget food shows, who happens to have a background as a former production assistant in the porn industry – argues that pornography has nothing to do with the enhancement and increased valuation of images. He argues,

Porn’s images are graphic, not stylized; real, not enhanced… If there were an accurate definition of food porn it would not be recipes in food magazines augmented with the sumptuous close-up photography. Instead, [it] would be the grainy, shaky, documentary images of slaughterhouses, behind-the-scenes fast food workers spitting in their products, or dangerous chemicals being poured on farmland.

And arguably, the “real” things are the things we would rather not think about or talk about, much less in our safe haven in the pages of the food magazine. The “real” things are political, and that brings us back to issues of class and of social hierarchies.

It’s entirely possible to think of these things through food and food magazines – we can simply start by asking the question, for who is all this? What kind of aspirations are we not only encouraged to have, but also told we would be better off having, through these images? Of course, this last question is true for all aspects of advertising. For example, even the most normal, unflashiest of cars get the flashiest and ultra-cinematic treatment of shots of either zipping through the city, going on gritty off-road adventures, or action movie appropriate car chases with Michael Bay-esque explosions in the background (of course all to pick up a beautiful lady in a shapely dress). International food magazines that are targeted to a more affluent audience – like Saveur or Gourmet – have articles about French vineyards and wine connoisseurs, about vacationing in Sicily and the best restaurants to go while you’re there. While there are magazines which are notches lower in snootiness, both international – like Bon Appetit and Food & Wine Magazine – and local – like Yummy and FOOD – there is always a premium put, well, on the premium. Or on whatever product an advertiser is willing to pay more for, but that’s a different story altogether.

But if food is an inescapable part of our experience, why are only the good-looking dishes and ingredients and brands hogging the limelight? We know that food is not always pretty, and there are interesting conversations to be had about them. In order to have truly productive discussions about how we can examine both ourselves and our community, we must take a closer look and dig deeper into the things we often take for granted – like what we eat.

Jack Goody, a social anthropologist, puts it best: he said that status, class, and prestige comprise probably the most important area signaled by food. In division of social class, there is a corresponding division of food and physical space. And of course, maybe not you, but much of us would like to emulate status – the kind of status set forth by lavish food magazines – and so there is an inevitable cycle that begins. But what about the other side of the coin? There is a whole food system out there, a whole world at odds with the haute cuisine world, and it is worth talking about too with the kind of focus and prevailing accessibility of the magazine. This is the food culture of the working class Filipino, of both the consumer and the merchant involved. The food that people like us eat for the novelty or photo-op are the foundations of communities that are afforded less. It is community.

And of course, it’s never really just about food. There are a truckload of issues that must be unpacked when talking about “poor food”, AKA the stuff you’d never see in a mainstream food magazine unless they were to be “re-imagined” by a professional chef and but on a clean white platter. Issues like appropriation, urban beautification, commercialization (which will be attempted to tackle later on), are ticking time bombs that when exploded, will hit the most vulnerable the first and the hardest.

We can imagine the food magazine to be more than what it is, and more than what it has been known to be. Hopefully we can agree that what we eat is political, whether we like it or not, because it involves other people, it involves regulations and prohibitions, and it involves money. So why should writing about it and talking about it stay deliberately apolitical and neutral? We can imagine the food magazine to be an avenue for education and mobilization – and not just towards making a trip to the supermarket or booking a reservation. And the soil is fertile for just that, because food is one of the few things that is universal, that is appreciated and looked forward to by all of us. And this publication will hopefully try to fill in at least a tiny gap in the space left behind by food magazines and other similar literature that move forward and towards a higher center, continuously.

References:

Gastronomica: The Journal of Critical Food Studies, Vol. 10 No. 1, Winter 2010; (pp. 38-46)

Goody, Jack. Cooking, Cuisine, and Class: A Study in Comparative Sociology. , 1982.

1 note

·

View note