Text

I've been doing a lot of volunteer fieldwork with these guys recently so I thought I might as well do an infodump about them here.

The pygmy bluetongue skink (Tiliqua adelaidensis) is one of the most unique and unusual members of the Tiliqua genus, which includes the true bluetongues as well as the sleepy lizard/shingleback. However, the pygmy bluetongue actually lacks the blue tongue the group is named after, having a pink tongue instead! As its scientific name suggests, it is quite a range restricted species, being found only in open grasslands north of Adelaide, South Australia, as far north as Peterborough. Historically they ranged more extensively across the Adelaide Plains, as far south as Marion, but due to the destruction of suitable habitat they now occur no further south than Kapunda.

While most bluetongues are notable for their large size amongst skinks, with several species regularly exceeding 30 cm in length, the pygmy bluey lives up to its name by measuring a measly average of 9 cm long from snout to vent. This is actually still a fair size compared to the average skink, but it's miniscule by bluetongue standards. Even more notable than their size however are their habits, for they are the only species of lizard that is specialised to live exclusively in old spider burrows! The burrows of both trapdoor and wolf spiders are used, but trapdoor burrows are preferred in most instances.

Pygmy bluetongues spend the majority of their lives within these spider burrows, leaving only to defecate, seek out mates and disperse. The average length of time a lizard spends in a particular burrow is highly dependant on the individual - some are sedentary and spend many years within a single burrow, while others will move around fairly frequently. As well as places to shelter and raise their young (they have parental care, it's very cute), pygmy bluetongues also use the burrows as ambush sites, waiting at the top for suitable prey, usually a mid-sized arthropod, to stray close enough for them to quickly dart out and drag them into the depths.

now here's the ambusher

The chief natural predators of pygmy bluetongues are raptors and brown snakes, and sheltering in the burrow is the main defence against both of these threats. Their burrows are often wide enough for a brown snake to enter, but not wide enough for them to open their mouths in - this means all the brown snake usually gets by pursuing a sheltering pygmy is an angry lizard attacking its face, forcing it to retreat.

The lazy lifestyle of the burrow-stealing pygmy bluetongues is certainly unique, and also explains why they have been such an elusive species since they were first discovered by Western scientists in the 1860s. Rarely seen or collected, their habit of inhabiting spider burrows remained undiscovered for the longest time, and by the 1960s they had become so hard to find that they were believed to be extinct. That was until, in 1992, a pygmy bluetongue was found inside the stomach of a roadkill brown snake by amateur herpetologist Graham Armstrong, confirming their status as a Lazarus of the lizard world.

The historic rediscovery of the pygmy bluetongue

(Image credit: Graham Armstrong)

Our previous assumptions of extinction were fortunately premature, but the pygmy bluetongue skink is in serious trouble nonetheless. While they are able to live in a variety of different grassland types, both native and exotic, the extensive modification of their entire distribution through cereal cropping and urbanisation has led to their populations becoming very small and fragmented, giving them a ranking of Endangered on the IUCN Red List. Almost all of these populations are on private land (often grazed by sheep), which makes protecting and/or studying them particularly difficult and complex.

However, when it comes to future threats to the species, climate change is easily the most worrying. As Australia becomes ever hotter and drier, their small remaining distribution is likely to become largely unsuitable, threatening the existence of the entire species. To combat this, researchers are currently investigating the viability of translocating populations further south to areas with cooler climates, providing a safeguard if they do indeed disappear from their remaining natural distribution.

But how do you study a lizard that lives exclusively in small spider holes? Well, if you want to catch them, there's only one tool for the job - the humble fishing rod. Not any special fishing rod either, just a regular rod with a poor mealworm shoddily tied to the end. Using this, you can engage in a tug of war with the lizards until, if they aren't being too difficult, you're able to pull them completely out of their burrow and catch them to perform the necessary measurements and processing. David Attenborough kindly demonstrates this technique in Life in Cold Blood, although in his case the lizard was steadfast in remaining in the burrow!

the sacred tool of the mighty lizard fishermen

returned to their abode

Two additional Fun Pygmy Facts:

Fun Pygmy Fact #1 - The closest living relative of the pygmy bluetongue is the sleepy lizard!

cousins!

Fun Pygmy Fact #2 - Wooden artificial burrows purpose-made for pygmy blueys have proven effective, and the lizards inhabiting them even tend to be in better body condition than those in natural burrows!

856 notes

·

View notes

Text

She's so perfect she just goes right back to doing her thing

52K notes

·

View notes

Text

the child seeks refuge

Spinifex Hopping-mouse (Notomys alexis) - Bon Bon Station, SA, November 2023

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

you’re not a true dasyuromorph disciple until you have a wild quoll walk up to you and sniff your phone

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

The south-eastern shores of Granite Island, South Australia, taken whilst clambering across the boulders in search of little penguin burrows for an annual census. My team didn't end up finding any active burrows (in general they're a lot less common on this side of the island nowadays) although we did find one with hatched eggs and a ton of down.

Also apologies for not posting much here but currently I am being slaughtered by uni work

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy international wombat day!

Southern Hairy-nosed Wombat (Lasiorhinus latifrons) - west of Blanchetown, SA, September 2019

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

This year has been quite rich for new dasyurids - a couple months ago we were gifted with a couple new planigale species from the Pilbara, and even more recently, a new paper by Newman-Martin et al. was released that found mulgaras, previously believed to be two species, are actually six. Tragically, the number of mulgara species out in Australia's deserts today remains two, as four of these species are already extinct.

But I'm getting ahead of myself. For someone who isn't a dasyuromorph disciple or other variety of Australian mammal nerd, what are mulgaras?

"Crest-tailed mulgara" on the left and "brush-tailed mulgara" on the right

(Image credit: Yingyod Lapwong & Owen Lishmund)

Mulgaras (Dasycercus) are a genus of carnivorous marsupials in the family Dasyuridae, which includes Tasmanian devils, quolls and a huge variety of other smaller but equally vicious predators. A fair size as far as dasyurids go, these rat-sized mammals are specialists of arid and semi-arid environments and were previously widespread across much of inland Australia, but their distribution retreated deeper into the interior of the continent following European colonisation. One trait that sets them apart from other dasyurids is their burrowing prowess - while many dasyurid species will inhabit burrows dug by other animals, mulgaras are skilled diggers that will construct their own extensive burrow networks, complete with a main entrance and several side tunnels and pop holes.

Trying to figure out how many species of mulgara there are has always been a source of great confusion to mammal taxonomists. The first species described was Dasycercus cristicaudata back in the 1860s, followed by D. blythi and D. hillieri in the early 1900s. These two new species were synonymised with D. cristicaudata in 1988, leaving one species of mulgara. In 2000, mulgaras were split back into two species, D. cristicaudata and D. hillieri, but a 2005 study believed the species in question had been misidentified - what had been thought to be D. hillieri was actually D. cristicaudata, and what had been thought to be D. cristicaudata was actually D. blythi. Confused yet?

Dasycerus blythi

(Image credit: Walter Baldwin Spencer)

Since then, the consensus has largely been that the two species of mulgara were the crest-tailed mulgara (Dasycercus cristicaudata) and the brush-tailed mulgara (D. blythi), both named after their distinctive tail shapes. However, the new paper turns this idea on its head yet again, with the most dramatic revision of Dasycercus species thus far.

Based on measurements of the teeth and skull, Newman-Martin et al. identified six different species within Dasycerus - this included D. cristicaudata and D. blythi, the previously invalidated D. hillieri, and three newly described species, D. wolleyae, D. archeri and D. marlowi. Despite this, the two previously identified living populations remained the only surviving species, with the other four being considered likely to be extinct based on their distribution. However, in one final twist, the surviving mulgaras previously considered to D. cristicaudata were found to actually be D. hillieri after all, meaning the type species of the genus is now among those believed to be extinct!

Of these species, three (D. cristicauda, D. hillieri & D. archeri) could be considered to be "crest-tailed" and two (D. blythi & D. marlowi) are "brush-tailed", while the sixth species, D. woolleyae, is usually crest-tailed but rarely brush-tailed. Given this, the appearance of the tail is no longer a distinctive characteristic of any of the species, but the authors stated that the common name could be kept for the extinct D. cristicaudata and potentially also the extant D. blythi. All other species required new common names, listed below:

Ampurta (Dasycercus hillieri)

Spinifex/brush-tailed mulgara (Dasycercus blythi)

†Crest-tailed mulgara (Dasycercus cristicaudata)

†Northern/sand mulgara (Dasycercus woolleyae)

†Southern mulgara (Dasycercus archeri)

†Little mulgara (Dasycercus marlowi)

What was previously believed to be the "crest-tailed mulgara", D. cristicaudata, is now the ampurta, D. hillieri!

(Image credit: Mike Letnic)

The fact that four species of mulgara are now extinct is not only inherently disheartening, but these also represent the first known dasyurid species to have disappeared in modern times. Dasyurids were previously considered to be more resilient to the impacts of invasive species and habitat degradation than other small marsupials, hence why no species had yet been lost, but the discovery of extinct mulgaras demonstrates that we are likely underestimating the impact that European invasion has had on dasyurid diversity. There may well be many other species that have already been lost without us ever realising they even existed.

But, while more than half of the mulgaras are tragically now extinct, we must also appreciate the precious species that remain. The brush-tailed or spinifex mulgara thankfully remains widespread and common, but the ampurta now occurs in only a small portion of its former range and is considered to be vulnerable to extinction - we must take careful steps to protect this enigmatic little marsupial, unless we want to see Dasycercus lose yet another species in the not too distant future.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

maleefowle <33333

hello wilds of tumblr

A few days down at Dhilba Guuranda-Innes National Park on the Yorke Peninsula last weekend delivered the goods as usual. I was mainly targeting peninsula brown snakes, which was a big success with 4 individuals seen! This big girthy fella (his name is Clifton) gave me particularly good views before I had to shoo him off the road.

I encountered lots of other cool guys along the way of course, including reintroduced tammar wallabies (woylies continue to evade me though), plentiful emus and even a surprise malleefowl.

(From left to right - tammar wallabies, tawny-crowned honeyeater, emus, malleefowl, painted frog, sleepy lizard/shingleback and eastern bearded dragon)

Herping season is now well underway so hopefully I can find more cool stuff if I manage to not die from uni work

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

I do not know this monitor's name, but I am hereby calling him Skrain

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

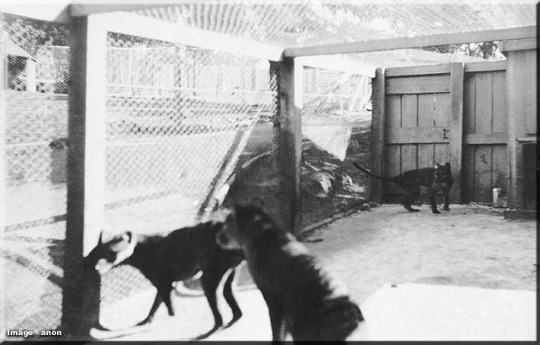

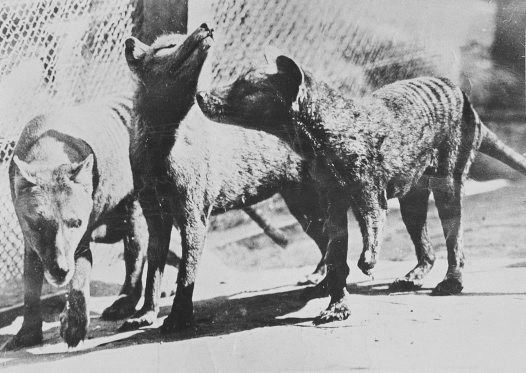

Three young female thylacines at the Hobart Zoo, one of which has an amputated forelimb

By: Michael Sharland & unknown photographer(s)

Ca. 1925

783 notes

·

View notes

Text

Went for a long drive north of the city today, didn't actually end up seeing much wildlife wise but Pinecone Jim and Blackbeard were there so it was all good

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Commune with the Common Eastern Froglet

The common eastern froglet (Crinia signifera) is, as its name suggest, a widely encountered species of frog in eastern Australia, as well as the island of Tasmania. This species can be found in many habitats, including deciduous eucalyptus forests, wetlands, and agricultural and urban ponds and dams. During the dry season, froglets will also shelter under logs or leaf litter to prevent desiccation.

C. signifera is one of the smallest species of frog, reaching only 3 cm (1.2 in) in length. Most individuals are brown, but specific markings can vary widely from region to region; some have dark stripes while others take on a more mottled appearance, though generally the belly is lighter than the back and head. Because this species is largely terrestrial, they lack webbing on their toes.

Like most frogs, the common eastern froglet consumes primarily insects, especially mosqitoes, cockroaches, flies, and small spiders. In turn, the species is food for a wide variety of predators including larger frogs, fish, birds, and small rodents. Because C. signifera is active all year round, its distinctive cricket-like "Crick crick" call can be heard in every season, typically as males attempt to attract a mate, though their coloration and small size makes them difficult to find.

Under ideal conditions, C. signifera mates througout the year. Once a male has attracted a female, typically by being the loudest male in an area, he will climb on top of an inseminate her in a common position known as amplexus. Afterwards, the female will lay upwards of 200 eggs attatched to a leaf or stick at the water's surface level. Though these eggs are a popular snack for predators, it only takes about 10 days for them to hatch; afterwards, hundreds of tadpoles will occupy the water for anywhere from 6 weeks to 3 months. Fully mature adults leave the water to find food and mates, but will often stay close to their original breeding ground.

Conservation status: The IUCN considers the common eastern froglet to be of Least Concern. Though the species is threatened by habitat loss, it is remarkably resilient to the chytrid fungus which has devestated so many other Anuran species.

If you like what I do, consider leaving a tip or buying me a ko-fi!

Photos

Stephen Mahony

Matt Clancy

David Paul

George Vaugan

105 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some scenery and common wildlife from an evening in Cleland National Park, both before and after dark

(Daylight critters - yellow-tailed black-cockatoo, New Holland honeyeater, sulphur-crested cockatoo)

(Creatures of the night - common ringtail possum, common brushtail possum, koala and southern boobook)

Additional invasive thug - look at those chompers!:

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

The lesser bilby (Macrotis leucura), less degradingly known as the yallara by the Wangkangurru people, is one of Australia's many many obscure recently extinct mammals. It was last seen alive by western observers in 1931, although based on First Nations knowledge (and a skull found under an eagle's nest) it appears to certainly have survived at least into the 1960s.

(Image credit: Oldfield Thomas’ Catalogue of the Monotremes and Marsupials in the British Museum)

The yallara was smaller and less colourful than the living greater bilby (M. lagotis), hence its description of as the "lesser" of the two species, but what it lacked in stature it made up for in ferocity. Unlike its larger cousin, the yallara was reportedly very aggressive and feisty, with Hedley Finlayson (one of the few scientists to observe the species in life, and the last) writing that they:

"...completely belied their delicate appearance by proving themselves fierce and intractable, and repulsed the most tactful attempts to handle them by repeated savage snapping bites and harsh hissing sounds, and one member of the party, who was persistent in his intentions, received a gash in the hand three quarters of an inch long from the canines of a male."

Although few observations of the species were made in life and much of their ecology remains a mystery, they may also have been more carnivorous than the living greater bilby. Investigations of stomach contents found large quantities of skin and fur from rodents, with only limited seeds and no insect fragments having been ingested. However, this information only comes from a small sample of individuals, so whether or not the yallara was the most predatory of all modern bandicoots will likely remain uncertain. They also differed in behaviour from greater bilbies by always blocking the entrance to their burrow after entering.

The species was only observed by Europeans in the harsh deserts of north-eastern South Australia and the south-east of the Northern Territory, but testimony from Aboriginal peoples indicates it also extended further west into the Great Sandy and Gibson Deserts of Western Australia. Being reported as common when last observed by Finlayson in the 1930s, its decline and extinction appears to have occurred entirely unobserved by western eyes, but it is likely that they were a victim of the usual troubles - invasive species and changing fire regimes.

128 notes

·

View notes

Text

The lesser bilby (Macrotis leucura), less degradingly known as the yallara by the Wangkangurru people, is one of Australia's many many obscure recently extinct mammals. It was last seen alive by western observers in 1931, although based on First Nations knowledge (and a skull found under an eagle's nest) it appears to certainly have survived at least into the 1960s.

(Image credit: Oldfield Thomas’ Catalogue of the Monotremes and Marsupials in the British Museum)

The yallara was smaller and less colourful than the living greater bilby (M. lagotis), hence its description of as the "lesser" of the two species, but what it lacked in stature it reportedly made up for in ferocity. Unlike its larger cousin, the yallara was reportedly very aggressive and fiesty, with Hedley Finlayson (one of the few scientists to observe the species in life) writing that they:

"...completely belied their delicate appearance by proving themselves fierce and intractable, and repulsed the most tactful attempts to handle them by repeated savage snapping bites and harsh hissing sounds, and one member of the party, who was persistent in his intentions, received a gash in the hand three quarters of an inch long from the canines of a male."

Although few observations of the species were made in life and much of their ecology remains a mystery, they may also have been more carnivorous than the living greater bilby. Investigations of stomach contents found large quantities of skin and fur from rodents, with only limited seeds and no insect fragments having been ingested. However, this information only comes from a small sample of individuals, so whether or not the yallara was the most predatory of all modern bandicoots will likely remain uncertain. They also differed in behaviour from greater bilbies by always blocking the entrance to their burrow after entering.

The species was only observed by Europeans in the harsh deserts of north-eastern South Australia and the south-east of the Northern Territory, but testimony from First Nations people indicates it also extended further west into the Great Sandy and Gibson Deserts of Western Australia. Being reported as common when last observed by Finlayson in the 1930s, its decline and extinction appears to have occurred entirely unobserved by western eyes, but it is likely that they were a victim of the usual troubles - invasive species and changing fire regimes.

128 notes

·

View notes