#wagnerrant reviews

Text

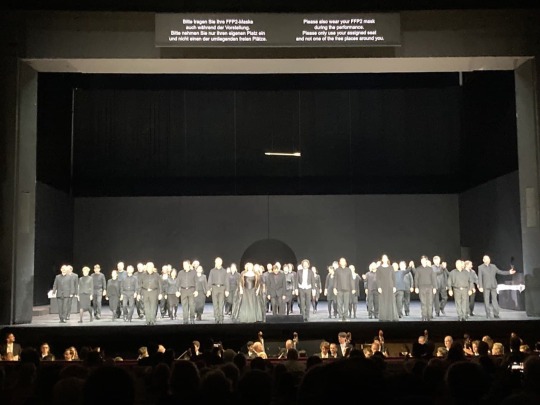

Wagnerrant Review #1: Double Parsifal

(Picture Source: here)

Work: Parsifal

House: Vienna State Opera

Date of performance: 11.04.2021

Team:

Director: Kirill Serebrennikov

Conductor: Philippe Jordan

With: Jonas Kaufmann, Nikolai Sidorenko, Ludovic Tézier, Stefan Cerny, Georg Zeppenfeld, Wolfgang Koch, Elīna Garanča

Notes:

This is not technically the first review posted on this blog. Still I decided to tag it as the No. 1, as it’s the first review ever since I (Admin Dichterfuerstin) decided to post reviews somewhat regularly. By that I mean that I plan on doing on or two per month, depending on my schedule and my mood. Most reviews will feature productions that have been around for longer, but I promise that I will watch and review every new production I can. I also take requests.

Trigger warning:

The following review of the new Vienna Parsifal discusses self-harm as it’s a prevalent element in Serebrennikov’s production. I ask you to keep this in mind when reading my text or watching the production. Don’t do either of this if you know you currently cannot deal with the subject.

Review: @dichterfuerstin

In the matinee talk preceding the premiere of the Vienna State Opera’s new Parsifal, director Kirill Serebrennikov announced a production that rather caters to an audience that doesn’t find the idea of devoting one’s whole live to serving a grail particularly appealing and struggle with the heavy role religion plays in Wagner’s monumental final work: According to Serebrennikov, his Parsifal portrays physical salvation just as in Beethoven’s Fidelio rather than religious one and focus less on myths and religion than on the development of the titular character, which is achieved by featuring two versions of the character. It is a rather radical concept, turning away from Wagner’s idea and calling for Serebrennikov’s own characters and storytelling. The director delivers a strong set-up in act one, but can’t avoid plot-holes and flat arcs.

The opera begins with Jonas Kaufmann’s face on a video screen. He appears on stage shortly after, as the old Parsifal, that watches act one from the front of the stage, reacting to all of his younger self’s decisions, mockingly lip-syncing Gurnemanz’ lines and singing his owns. He is supposed to recollect the events from act one and two and is already remembering, even though his younger self only goes on quite late into act one.

Until Parsifal’s entrance according to the libretto, the young Parsifal only is present on screens above the stage, where he is eventually shown killing another prisoner nicknamed “Swan”. Having Parsifal kill a human instead of an animal works. Not only because it fits Serebrennikov’s setting better. It also creates a bigger contrast between the young and the old Parsifal.

However this is the only occasion where the projections on the three screens serve the plot. During the rest of the opera they show images underlining the cruelty of prison life, creating an atmosphere but having no impact on what happens on the stage whatsoever. By act three they’re even somewhat distracting.

Behind Kaufmann, under the screens, is the huge and elaborate set, a prison, in where the young Parsifal such as all the knights are inmates. The audience watches them working out, fighting, and bribing the guards for cigarettes. One prisoner sleeps on a bench, to give Gurnemanz a prompt for his wake up-call.

Even though Gurnemanz’ position is lower than usually, when he’s not a prisoner but instead the factual leader of the grail’s knights, he’s the character changed least in this production. He may hide his cigarette’s from the guards, but he still commands over the knights and pages, and tells the story about Amfortas, while tattooing the other prisoners with mythical and religious symbols to remind the audience of Wagner’s plot and setting, and maybe to establish Gurnemanz as a somewhat religious character, as he proceeds to proclaim Parsifal the new king in a very holy service-like ceremony in act three, after singing at a random metal pole, since a spear isn’t needed in this production.

Amfortas, some kind of a leader of the resistance, as we learned in the matinee talk, was never hurt by someone else but instead suffers from mental illness and self-harms. He needs to be saved from himself. Amfortas’ father, Titurel, is long dead, he seems to speak to his son from above. He is partly responsible for Amfortas’ illness The unveiling of the grail is substituted by a mental breakdown, in which the prisoners try to stop Amfortas from giving himself even more wounds and pain.

The last main character to appear in act one is Kundry, in this staging a journalist investigating the prison and smuggling medicine for Amfortas. She is sung by Elīna Garanča who delivers an impressive role debut. While some journalists who had the opportunity to see the opera live claim that she seemed to struggle with combining the staging and the score, both her singing and her acting came across amazing on the recording. She plays Kundry not like a singer but like a good actress.

It’s not Garanča’s fault that the character of Kundry eventually falls flat. According to Serebrennikov she was supposed to be a strong woman with a conflicting past, but not much of this is present throughout the opera. She starts out as the seemingly independent Journalist, who later turns out to be an employee at Klingsor’s magazine “Schloss.” He assaults her, she shoots him. This is also Klingsor’s entire role in this Parsifal. He doesn’t have any interaction with Parsifal and also seemingly no impact on him at all, a consequence of stripping the plot of Parsifal of important story elements such as the grail, god, and the celebacy of the grail’s knights.

Kundry seems interested in Gurnemanz’ tales, collecting pictures of the prisoner’s tattoos, being clearly interested in the myths and the prisoners, but we never learn her motivations. Eventually her arc is completed by her walking off the stage, arm in arm with Amfortas, who freed himself from his father by throwing out his ashes and was then healed through Kundry’s kiss. This would be a satisfying ending for an action film, considering the source material and the set up from act one it’s a lazy, far to easy way to resolve both of their character arcs.

Unfortunately, the entire ending is dissatisfying. Parsifal returns to the prison as his old self, yet his young alter-ego appears later on and kisses Kundry, the old Parsifal doesn’t mind, no matter how determined to separate them he was back in act two. After that Serebrennikov makes a surprising return to the libretto: Kundry washes Parsifal’s feet, he is made the king and baptises her, before fulfilling the production’s premise as a salvation opera. All the prisoners can finally leave the prison and reconnect with freedom, this production’s holy grail. Gurnemanz even takes his time to wave Parsifal good bye, who remains inside the prison. It’s a symbolic ending, in the libretto Parsifal is now responsible for the grail, a prisoner of the grail if you will. However this third act end ending fail to connect with the preceding acts.

The production falls flat on more than just a few occasions, however the cast and music manage to make up for it.

Most outstanding is Georg Zeppenfeld as Gurnemanz. Not only is his beautiful bass voice made for this characters, no other Wagner role is so incredibly fitting for him, he also manages to combine the prisoner and commanding Gurnemanz through his acting. Overall the acting is strong for a bunch of opera singers, who still have a reputation for being great singers but struggling with acting. There’s

Elīna Garanča delivering her impressive role debut, as well as Ludovic Tézier as Amfortas, appearing perfectly hurt and pained as he drags himself over the stage.

Parsifal Jonas Kaufmann is neither a debutant nor a born Wagner-Singer. His approach to Wagner’s music is rather italien, he values emotion and beauty over heroicness. It’s melancholic, well-fitting for this old Parsifal remembering his youth.

Kaufmann and his alter-ego actor Nikolai Sidorenko work together to create a character and they do it well. The only downside of having two Parsifals, besides some confusion on who is the active parsifal especially during act three, is that next to the fantastic actor Nikolai Sidorenko it becomes obvious that acting isn’t Kaufmann’s strong suit. He often resorts to a preset set of gestures, other than most of his colleagues who are their characters throughout the whole four hours long performance.

Last but not least, it’s the orchestra that is the center of nearly all of Wagner’s music. Philippe Jordan, the new musical director of the Vienna State Opera, leads his orchestra through this exhausting opera fluently, making every single Leitmotiv and their variations perfectly clear. But especially the solo parts stand out. But it’s also the unexcelled charm and emotionality of the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra that makes this performance so fitting and so beautiful. Even on screen, through speakers, this orchestra feels live, and alive.

This Parsifal is mostly worth listeing to, but also worth watching. While Kirill Serebrennikov couldn’t quite do justice to the setup for a deep and thoughtful story he created in act one, he was able to create a captivating production, with an ending that is good for Parsifal nights, where you want to leave the theatre or laptop with the feeling of having watched a happy ending instead of having been confronted with four hours of Wagner’s music-religion.

#wagnerrant reviews#parsifal#richard wagner#opera#wagner opera#review#vienna state opera#not a rant#officialwagnerrant

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Due to pre-premiere stress the next review will be posted around the middle of July. To make up for being late it’s gonna be a real special one: The production is TANNHÄUSER at the Bayerische Staatsoper and for the first time I will review a production I saw live.

- dichterfuerstin

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wagnerrant Review #2: The sea on land

Work: Der Fliegende Holländer

House: Klaipėda State Music Theatre

Date of performance: Streamed on Operavision on 02.04.2021

Team:

Director: Modestas Pitrenas

Conductor: Gediminas Šeduikis

With: Almas Švilpa, Sandra Janušaitė, Tadas Girininkas, Andris Ludvigs, Rafailas Karpis, Dalia Kužmarskytė.

Review: @dichterfuerstin

If just one of Richard Wagner’s operas is fit for outdoor performances, it is with no doubt Der Fliegende Holländer. Set at the sea, it almost demands a production staged open air, with the sea or any kind of water as it’s backdrop. Not much surprisingly, the Klaipėda State Music Theatre’s production of Der Fliegende Holländer is by no means the first of it’s kind. But But while other opera houses, for example the Theater Regensburg in southern Germany, went for semi-staged or even concertant productions, the Klaipėda State Music Theatre put on a fully staged and choreographed Holländer. The outcome is visually impressive.

To be frank, the production wouldn’t bet that special if it was just your normal indoor staging. Two big scaffolds, one on each side of a big platform, mark the stage, some seemingly actual harbour buildings work as a backdrop. The Dutchman himself appears on a boat. This ship is not on the water, as far as one can see it on the video it’s on railroads. The setting in a harbour is established by gold being transported in an elevator and the women unloading boxes from a boat. And in terms of Personenregie and choreography for the sailor’s chorus, director Modestas Pitrenas uses quite simple tricks as well: Senta and Erik having their emotional duets on oposite sites of the stage, to show how far away they are from each other, giving Senta big movements for her first aria, making it a dramatic storytelling. The sailors perform a little dance for Steuermann lass die Wacht. What Pitrenas does works, but it isn’t special.

It’s the water that makes on wish to have seen the production live. Not one scene of the opera is played on actual water, it’s all on land, but it doesn’t matter, theatre is about the illusion and the illusion works.

The art of director Modestas Pitrenas and probably even more of stage-designers Dalius Abaris and Sigita Šimkūnaitė gets the sea on land. They create a storm-shaken ship by having water running through the scaffolds, making sure nobody stays dry during the entire first act of the opera. This feeling of being on the stormy sea doesn’t only work for the audience at the scene. It translates strikingly through the recording as well and makes a captivating video. In person, it must have been breath-taking.

Unfortunately however, the performance of the singers cannot quite hold up to the impressive stage design. Some things can of course be excused, for example that the opera is slightly shortened. It doesn’t hurt. It’s also okay for the singers and the orchestra using microphones. The production was open-air after all and cannot profit from theatre acoustics, it even has to accommodate possible wind and other negative weather situations. A big problem when playing open-air is also the placement of the orchestra. There’s a reason for why the pit is usually located beneath or in front of the stage. In Klaipėda, the orchestra sits on a small platform next to the stage. The sound is well mixed and everything is nicely audible using earphones.

For me as a German listener the strong accents many of the performers have are distracting as well. However one has to consider that the production was not made for German people and most of the audience members probably did not even notice the accents.

Unfortunately, though, not all of the performers seem to be opera singers. Many lack vibrato or have a strong wobble, sound strained and audibly struggle to hit their respective role’s notes, something that cannot be helped by giving them microphones. Notable exceptions of this are Daland (Almas Švilpa) and Erik (Andris Ludvigs).

The orchestra on the other hand, especially the soli, played beautifully. Personally I found them a little too soft at the parts where the music has to explode, for the storm- and Holländer-motif. It could’t really match what was going on on stage. But it was pleasant to listen to, and maybe sounded more impressive live.

Overall this Holländer is very nice to look at. However it does not seem to be marketed at opera fans, more at theatre- or just event people that want to see a nice open air spectacle. If you have a free evening I’d recommend giving it a shot anyway. I had fun, even though I did not always like the singers.

#wagnerrant reviews#Der Fliegende Holländer#Richard Wagner#opera#Wagner Opera#review#klaipeda state theatre#not a rant

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wagnerrant Review #6 - Tristan und Isolde

Work: Tristan und Isolde

Bayerische Staatsoper

Date of performance: 31.07.202

Team

Director: Krzysztof Warlikowski

Conductor: Kirill Petrenko

With: Jonas Kaufmann, Anja Harteros, Okka von der Damerau, Wolfgang Koch, Mika Kares, Manuel Günther, Dean Power, Christian Rieger

Review: @beckmessering

Here’s an entirely hypothetical question: when not very familiar with an opera, is a Regietheater production with hotly anticipated role debuts the best opportunity to form an emotional understanding? Answers may vary, but take it from a someone whose opera education had a shamefully large Tristan-shaped hole: Krzysztof Warlikowski’s Tristan und Isolde at Bayerische Staatsoper is a production to to gnaw on – conceptually elusive and a puzzle with many pieces, but finally a great reward in scenery and in music.

Jonas Kaufmann lends Tristan his well-known baritonal timbre, although it’s not quite as prominent as usual. His voice is dense and rich, though not artificially darkened, and brings delicate piani as well as strength to the role. The third act with Tristan’s near-incessant monologues of increasing volume and intensity provide an audible challenge that doesn’t leave Kaufmann’s voice untouched: he sounds somewhat taxed by the time he’s finally allowed to collapse once and for all. Granted, it’s a punishing and brutal feat; the sheer amount of energy required to sing oneself to death likely isn’t equivalent to the amount a badly wounded man would still have. Kaufmann thus doesn’t quite look to be on death’s door despite a shirt soaked in progressively darker shades of red, but he nonetheless he provides a well-grounded interpretation of one titular character. He steers away from classic hero territory into something more nuanced and disconcerting if one only looks closely enough – Isolde, for that matter, hits the nail on the head when she replies “Frag deine Furcht!” to his “Und welchen Feind?”. He’s scared – or perhaps haunted by thoughts that won’t leave him alone, unable to keep his hands and his gaze still when not singing. He doesn’t outright long for death, but from the very start, he sure doesn’t seem at ease with life, either. Something isn’t quite right with Tristan – and just the right person is needed to unleash it fully.

That just-right-person is Anja Harteros as Isolde, who deserves perhaps the audience’s grandest ovation. Vocally, she is still in excellent shape until the last measures of her delicately sung Liebestod, having preserved her gleaming heights and pristine sound over all three acts. Her middle register, uniquely crystalline and incredibly poignant, could conceivably serve to distinguish her voice from thousands. Yet her singing by far isn’t too pretty to show feelings – Harteros’ voice suits a seething young woman with a rich inner life that progressively unfolds throughout the opera. “Lass’ uns Sühne trinken!“ is an actual threat, one that Tristan wholeheartedly embraces. After losing herself in love in the second act, she reemerges from it lonely and bitingly aware of it. Her grief, like her rage, is controlled yet bone-deep, and it inevitably leads her to die. Perhaps something wasn’t quite right with Isolde, too.

Wolfgang Koch sings Kurwenal with a vivacious, robust baritone that energetically prizes life – a great contrast to Tristan’s inclinations. However, Koch stays far from acting clownish, particularly in the third act, where he wears the worry about his friend on his sleeve, but ultimately remains powerless against Tristan’s impending death. While the latter ecstatically sings himself into delirium, Koch remains comparatively static, demonstrating his character’s inability to help and by extension, vastly different attitude towards life.

Okka von der Damerau’s Brangäne is a well-meaning figure trying her best to put Isolde at ease in this admittedly highly tense situation. While initially reminiscent of a caring aunt, the two women’s bond becomes far more sisterly in nature once the first act’s dialogue – or perhaps conspiracy – around Isolde’s secret potion stash unfolds. She braves the act’s finale with top notes of impressive volume and provides a surprisingly bright, silvery metallic sound for a mezzo. Considering the standout dynamic between the two women, it’s perhaps fitting that her voice blends so smoothly with Isolde’s and even elicits comparisons to a soprano’s sound.

Mika Kares as King Marke packs much disappointment into his clear, well-articulated bass, though it’s about far more than the good old besmirching of honour – this betrayal is personal to him and runs deep. Regrettably, he’s given little to do once he has discovered the wrongdoers in each other’s arms except stalk back and forth between Tristan and Isolde, so he resorts to various pronounced eye movements that verge on accidentally amusing. Brangäne’s single look of horror upon assessing the scene says more than any eye movement could.

Kirill Petrenko’s conducting is fluid, gentle, a statement in and of itself never at the cost of the singers. He crafts the prelude into an intensely lyrical treat, promising much and delivering on that by keeping the orchestra’s sound light yet rich enough to satisfy. He eschews heaviness, but never at the expense of intensity. Particularly the tense moments of the first act are played out very well, and the performance is audibly a successful collaboration between singers, conductor and orchestra: the singers are never drowned out, the orchestra makes its mark, and Petrenko himself brings both together with excellent timing to savour a spectrum of emotions.

Director Krzysztof Warlikowski transplants the setting into a wood-panelled room with high ceilings that traps all characters within its high ceiling, allowing them little escape from what troubles them. This room serves as a continuous backdrop throughout all three acts, although each act adds elements uniquely suited to the current happenings. During the prelude, two silent dancers dressed as almost frighteningly life-like dolls, one male and one female, appear. Their movements are tentative, childlike, evocative of a fragile state as they interact and cautiously touch each other. In the second act, a projection that previously illustrated the view outside a ship’s porthole serves as perhaps an emotional window into the lovers’ psyche. It shows grainy, black-and-white footage of Isolde sitting – waiting – alone on a bed, suggestive of a security camera’s spying eye. In the film, Tristan enters only during “O sink hernieder” and the two sit silently next to each other sans any eye contact, while the real-life Tristan of course has of course entered the stage some time ago. While both of these elements receive their resolution in the final act, the act two film is already subtly reflective of the singers’ actions onstage. While the first act was far more dynamic in terms of interaction, much of this movement disappeared once Tristan and Isolde fell in love, causing the lovers to remain comparatively static during their time together. This takes some time to notice and even more time to get used to, but it allows for much inference on the nature of this love. It’s of the paralysing sort, and it can’t coexist with normal life and regular interaction. There is wallowing in this love or interacting with the rest of the world – but ultimately, a choice will be have to be made. It’s a consuming love, yet clearly not of the physical or even romantic sort, judging from the frequent lack of touch and eye contact – perhaps it’s more of a kinship, a matter of two people having found a part of themselves in each other that they had lost. In any case, the concept avoids the stylisation of Tristan and Isolde’s love as something bright or pure – they may be enraptured, but their state of intoxication doesn’t induce wishful thinking in the audience. The music, more than anything else, connects the lovers with the onlookers. It’s a maddeningly subtle concept of interaction that can easily be taken as stiff or confused with lack of ideas, and the only time it doesn’t pay off is during King Marke’s confrontation in the second act, where Mika Kares isn’t given enough space to physically communicate the emotions of the normal world.

The place of Tristan’s youth in the third act finally unites the previously introduced ideas: Tristan awakes at a table surrounded by dolls seated at a dinner table and dressed like the one representing him in the prelude. As he recalls the early death of his parents, the suggestion that he grew up in a boarding-school atmosphere and carried the burden of being orphaned plants the core idea that he comes from a place of loneliness. Absent a place of emotional safety and affection, his outlook on life is shaped by the inner fragility and unsteadiness he was instead endowed with, and causes him to escape into a love – or a construct – that opposes this life. The question of whether his love is static and at odds with life by nature or rather by Tristan’s nature remains somewhat open, but both are conceivable. During Isolde’s Liebestod, the projections return, showing the lovers lying side by side on the bed again while the room floods with water. As the two inevitably drown, they gaze into each other’s eyes for the first time while the film turns colourful. What initially seems oddly romanticising of death and clichefully pleasant becomes exceptionally poignant when seen as the lovers’ attitude towards death and final fulfilment rather than the director’s views.

It’s an interpretation that becomes more wrenching the longer one thinks about it – multi-layered, elusive, and it refreshingly strays from unduly heroic characterisations that don’t fit the story well. Admittedly, the focus is somewhat aimed at Tristan, and by necessity of the set, much of the psychologization of Isolde in the first act has to occur in the same setting Tristan’s mind will eventually be dissected in. Partially bound by the story and partially by the staging, she can’t be given the same due, which, considering Harteros’ standout Isolde, is a slight shame. Nonetheless, the production doesn’t feel uneven, and when adding music and singers, it becomes a harmonising whole entity. I myself may have closed my eyes in an attempt to fall in love, and I don’t see anything more befitting this opera.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wagnerrant Review #5 - Not enough Holländer

Work: Der Fliegende Holländer

Bayreuther Festspiele

Date of performance: 25.07.2021

Team

Director: Dmitri Tcherniakov

Conductor: Oksana Lyniv

With: Georg Zeppenfeld, Asmik Grigorian, Eric Cutler, Marina Prudenskaya, Attilio Glaser, John Lundgren

Trigger warning: S*icide mention, mass m*rder mention.

Review: @dichterfuerstin

Dmitri Tcherniakov’s Der Fliegende Holländer looks more like the latest episode of Netflix Germany’s Dark than like an old sailor’s tale. The audience is presented with the foggy image of a small town. Grey brick buildings, grey pavement, grey streetlight. Just the rubber boots that are part of most of the costumes pay a small tribute to the original setting. Maybe the small town is a fishing village. And just like the sets, the story told on stage has little to do with what’s written in Wagner’s libretto.

It’s a crime story, rather than a mystery.

Instead of being a sea captain, the Holländer appears as a man referred to as “H” who according to the writings on stage has a “strange, returning dream”. This dream, or rather memory, is shown during the overture. “H” is shown as a little boy whose mother has an affair with no one less than Daland himself. When her affair is discovered, the village shuns H’s mother to the point where she commits suicide in front of her son.

The set is a little too calm for how booming and fast Oksana Lyniv’s overture is, and it’s radically different to what Wagner wrote in his libretto, but it works with the music pretty well during the first two acts. He remembers Daland, Daland has a vague idea who the stranger is. And Mary, excellently sung by Marina Prudenskaya and in this production upgraded to Daland’s wife and Senta’s (Step-)mother, seems to know exactly. She carries the Holländer’s picture around and is visibly scared of him. Add to this the perfectly spooky and mysterious atmosphere. It takes a while for the audience to realise that the “dream” is in fact a memory that the wondering of how much of it is true and what’s going to happen is always prevalent, especially every time the Holländer walks past the house where his mother died.

The characterisations in Tcherniakov’s production are on point. Mary is just strict enough, Georg Zeppenfeld’s Daland is not only audibly full in character, his facial expressions are on point throughout the entire opera. Of course, the modern setting does make him basically trading away Senta more awkward and actually less understandable.

Especially since Senta is very young. Daland’s daughter doesn’t seem much older than sixteen thanks to Asmik Grigorian’s brilliant acting. She’s way younger than the Holländer, even Erik seems too old for her. But she’s sassy. She’s impudent, she smokes, she dyes her hair. She isn’t that dreamy girl carried away by the tale of the mysterious dutchman, she rather seems to mock him, and yet falls in love when she meets him in at dinner. Asmik Grigorian conveys all of this not only in her acting but also in her voice. Of course, she sounds older, but it doesn’t matter. The sound is clear, the diction well, and the Festpiel-debut successful.

John Lundgren’s Holländer is equally well-acted. Though he doesn’t do much. The Holländer’s a very passive character, spending most of his time watching, and being strange. He constantly seems out of place thanks to his white sweater in contrast to the rather brown costumes everyone else, including Senta, wears. Making the Holländer stand out is a standard decision, but it is very well executed by costume designer Elena Zaytseva. Lundgren’s voice fits as well, apart from becoming audibly strained in act three. He isn’t as booming as most Holländer’s, rather pretty, but that is perfect for this characterisation, where the Holländer isn’t punished for cursing on God but traumatised because he saw his mother getting hounded until she killed herself. He isn’t even a captain, he’s alone. To the end of the opera, a handful of men he met at the pub who listened to him telling his story become his crew and get spared when the Holländer shoots into the crowd gathered on the town square to celebrate.

For two hours the audience wonders where the production will lead. Will Senta die where the Holländer’s mother died? Will they die together as it’s written in the libretto? And in the end, it’s a mass shooting and arson committed by the Holländer. Although this ending makes perfect sense for the Holländer the way he’s set up in Tcherniakov’s production, it’s a somewhat disappointing ending.

Daland doesn’t even appear on stage. Shouldn’t he have some kind of reaction to the Holländer’s doing? For the first time Grigorian’s acting isn’t sufficient enough for the audience to understand what she’s feeling, the production doesn’t really provide good answers. And while making Mary Daland’s wife made her more important, the character didn’t have enough to do to explain why it’s her who eventually shoots the Holländer and then has to be cared for by Senta.

The ending is an ending for a crime story. It’s a thriller, but not the one Wagner intended. For the Holländer, the focus should be a little more on the bond between Senta and the Dutchman. But on it’s own, the story told by Dmitri Tcherniakov is interesting and thought-through.

At least Oksana Lyniv’s conducting stays consistently emotional. The 43-years-old Ukranian conductor makes her Festspieldebut in this production, as the first ever woman to conduct an opera at the Bayreuther Festspiele, and she does it well.

She manages to remain unfazed by the many interruptive noises in this production. Be it chairs or tables collapsing in act one, or gunshots in act three, and she’s singer-friendly. Maybe a little too singer-friendly, sometimes the orchestra does seem too much in the background. But overall, she does an amazing job. Her overture stands out the most, but the entirety of her Holländer is nothing short of beautiful. And fulfils the most admirable task of holding orchestra, soloists and chorus together, which is especially difficult this year: Due to the pandemic, half of the chorus acts on stage, the other half sings in the chorus-hall and their singing gets transmitted into the audience via speakers. And somehow this needs to sound natural – and be on time. Lyniv and chorus master Eberhard Friedrich work together well, so the audience doesn’t hear that something’s different this year.

This by the way also isn’t noticeable in the production. Neither does the stage seem empty nor are there six feet distance between every two singers. It’s a standarf production, and just as it’s standard for Bayreuth, director Dmitri Tcherniakov got booed by the audience. Undeserved, it’s a captivating and interesting to watch production, but it won’t make history as one of the strongest Bayreuth-productions either - it just isn’t enough Holländer.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wagnerrant Review #4 - Mishaps and Emotion

Work: Tannhäuser

House: Bayerische Staatsoper

Date of performance: 11.07.2021

Team

Director: Romeo Castellucci

Conductor: Asher Fish

With: Georg Zeppenfeld, Klaus Florian Vogt, Simon Keenlyside, Dean Power, Andreas Bauer Kanabas, Ulrich Heß, Martin Snell, Lise Davidsen, Elena Pankratova, Sarah Gilford, Soloists of the Tölzer Knabenchor

Review: @dichterfuerstin

With Jonas Kaufmann’s Tristan debut right next to Anja Harteros’ Isolde debut (Watch the stream on staatsoper.tv, July 31st, 5PM CEST, it’s worth it), it’s hard to believe that the event I was looking forward to the most in the 2020/21 opera season was a performance of a four-year-old production that I’ve seen online before. But it was and so I did everything to get my hands on tickets for this season’s only performance of Tannhäuser at Bayerische Staatsoper. I cannot describe how happy I was when I got them and how sad I am now that it’s over. I hope that writing this review will help me revive those five hours at Bayerische Staatsoper – truly a special evening.

The best part of the entire production is the opening scene. Romeo Castellucci uses the fairly long overture and Venusberg music to visualise Tannhäuser being lured to Venus. A group of topless woman shoots arrows at a picture of a human eye, later the picture changes to that of a human ear, bewitching Tannhäuser’s senses until he gives in. A Tannhäuser-double walks on stage and climbs up the backdrop.

This entire scene is choreographed flawlessly, every arrow compliments the music, and their placement on the backdrop is planned in a way where it works both for the picture of the eye and for the ear.

Castellucci did everything himself in this 2017 production of Tannhäuser. He directed, designed the sets, the costumes, and even the lighting. Solely the choreography by Cindy van Acker isn't his work. The result is a stunning unity of visuals on stage.

It’s those that tell the story, not the characters. Elena Pankratova, who returned to the production to replace Daniela Sindram, pretty much only had to sit around as Venus, but she doesn’t have to move. It’s the mountain of flesh she’s sitting in, and the fact that both her and her lovers seem to melt away in fat and skin, that explains to the audience that Venus is a personification of both Lust and Gluttony.

In act two, the singers could just stand in the wings to sing their lines. Not their acting tells us how they define love, but a single word written on a cube serving as altar and speaker’s desk at the same time. When Tannhäuser finally bursts out the confession that he’s been with Venus the words disappear and instead black colour gets spray-painted around in the cube. The black, forbidden aspect of Tannhäuser’s soul.

The entire production gradually becomes blacker. While act one is even fairly colourful – fleshy pink for Venus, and bloody red for the Wartburg-knights’ costumes the deer they’re hunting, act two is white with only implied skin and nudity, though a lot of it, and act three is black until the curtain-call.

This third act is the most impactful part of Castellucci’s production. It doesn’t raise nearly as much questions as act one and two – why do the knight’s costumes look like BDSM-fetish outfits? Why are there feet all over the stage during the Sängerkrieg? It shows the passage of time in the most impactful way. While more and more ridiculous numbers appear on the black screen – millions and millions and millions of year pass, the audience is shown the process of corpses rotting. And it’s not Tannhäuser’s and Elisabeth’s corpses, the names on the graves are those of the singers – Klaus and Lise. The message of this image? Tannhäuser and Elisabeth can’t be together in this timeline, but their story surpasses their lifetime.

But no matter how powerful the imagery: Once again the singers do pretty much just stand and sit around while the stage speaks for them. Thus they can’t convince through their acting choices, but have to put everything into their voices.

And they do. Especially Georg Zeppenfeld convinces as Landgraf Hermann. He is probably the most reliable singer of our time, he doesn’t seem to have off-days. And as always he’s at his best in this performance. His voice carrying easily through the performance and singing a dignified, powerful Landgraf. And no matter what happens, he always remains calm.

The opposite of calm is obviously Tannhäuser. Klaus Florian Vogt debuted the role in this back in 2017 and hasn’t been replaced for even one year ever since. With good reason: His unusually light voice is a perfect fit for the sometimes too self-assured, sometimes insecure Tannhäuser. In addition to this, Vogt noticeably puts his whole soul into his performance, even though he apparently did not have the time to fully revise his, which led to a kind of sad “In ihr liegt in Maria” instead of the famous “Mein Heil liegt in Maria” and other mishaps. He makes up for his mess-ups by making his Tannhäuser especially emotional. He’s not afraid of letting a character’s emotions influence the sound and spices up the Romerzählung by singing with a different voice when quoting the pope, in comparison to when he’s just Tannhäuser.

Lise Davidsen as Elisabeth is equally impressive. Having heard her as Sieglinde just some weeks before, I remembered her sometimes not being loud enough to get over a Wagnerian orchestra. This time however, she was in perfect form and every single one of her notes reached the audience, even the more quiet and scared lines in act three. I loved those especially. Davidsen dares to give her Elisabeth an insecure, questioning tone for “Sie sind’s” and “Sie kehren heim” and thus makes the audience really understand how much she fears Tannhäuser not coming back.

With their voices harmonizing perfectly, with their acting skills, their creativity and emotion, Davidsen and Vogt make a great duo and we can only hope to hear them together in many more productions – next up is Die Walküre in Bayreuth.

The most impressive performance, however, delivers Simon Keenlyside as Wolfram von Eschenbach.

Stepping in for another singer with just one day’s notice is hard, especially if this singer is Christian Gerhaher, munich’s favourite baritone. But Keenlyside, most well-known for his Mozart-interpretations mastered his unexpected Wagner-Challenge with ease. He acted as if he’d been rehearsing the production for weeks, and his big voice filled the Nationaltheater with ease, while always embracing Wolfram’s character. Not once he slipped into just singing his lines. Of course one could criticise that he never seemed to keep his hands still, unusual, when you’re used to Gerhaher’s interpretation of Wolfram von Eschenbach, but let’s be honest: This would be nothing more than beckmessering.

Keenlyside is not the only one stepping in, though the others had about two weeks to prepare for their roles. Elena Pankratova, returning as Venus for Daniela Sindram, who was supposed to take over the role this season, and like Zeppenfeld and Vogt an original cast member in Castellucci’s production sings, as if she had planned to come back to Venus, her strong Soprano outshines the unflattering costume her director gave her.

Last but not least, Asher Fish conducted the performance for Simone Young. While it would have been nice to see a female conductor for diversity’s sake, opera is a world still very much dominated by men, one cannot complain about Fish’s conducting. He works out orchestra parts that are hardly noticeable, sometimes works them out too much, like when Tannhäuser is discovered by the Wartburg-society in act one he pronounces the more rhythmic parts so hard the music ends up sounding like traditional dance music you’d expect at German fairs. But just like Vogt seems to have finally found his libretto in act two, the conducting gets more balanced and with sensible dynamic- and tempo choices Fish gives the opera the amount of tragedy and sadness it needs, together with the mixture of euphoria and anger Tannhäuser’s descriptions of love in act two need.

Even if not everything went well – the choir could have been more balanced, the very first set change in act didn’t go as smoothly as it’s supposed to go, and not everyone knew their lines – the performance was touching, very nice to see, and fantastic to hear. I’m so glad to have been there, and cast and crew deserved all of the applause they got – certainly more than ten minutes of clapping and cheering.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wagnerrant Review #3: Das Rheingold im Hafen

Work: Das Rheingold

House: Theater Regensburg

Date of performance: 03.07.2021

Team

Director: Andreas Baesler

Conductor: Chin-Chao Lin

With: Adam Krużel, Brent L. Damkier, Oliver Weidinger, Philipp Meraner, Seymur Karimov, Selcuk Hakan Tiraṣoğlu, Vera Egorova-Schönhofer, Deniz Yetim, Tamta Tarielashvili, Anna Pisareva, Vera Seminiuk

Review: @dichterfuerstin

It’s already a tradition and always sold out: For the third time Theater Regensburg rented out the Bayernhafen, a port in the east of Regensburg, to put on an opera. Two years ago, it was Tosca, four years ago, the first open air spectacle of this kind, it was Der Fliegende Holländer. This year the theater took on the ambitious challenge and produced Das Rheingold. Needless to say, when 800 additional tickets got released, I grabbed a front-row seat and went to check out this production.

Abridging an opera is one thing. Abridging a Wagneropera is another. With lyrics and music being so tightly connected, with leitmotifs and nothing even remotely resembling an aria, it seems nearly impossible to put on anything that isn’t the original. Theater Regensburg did it anyway: They staged a version of Das Rheingold edited and abridged by Eberhard Kloke, lasting merely 90 minutes, reducing the libretto and completely omitting Donner an Froh. I’m not sure why they went for an edited version. There aren’t any restrictions on how long an opera can be, and as long as you have a testing concept you can also have productions of unlimited size. They also don’t lack singers. I could name a handful of singers working at Theater Regensburg not employed this evening.

Much to my surprise the abridged version worked out musically. Without having a score or libretto at hand, which I obviously did, you’d barely notice the changes, especially as a non-Wagnerian. However, some of my favourite parts got omitted. I never again want to se a Rheingold without Donner’s iconic call.

The abridging was actually most noticeable in the plot. Due to shortened conversations the only characters ever mentioning Freia’s golden apples were the two giants, which resulted in a rather sudden decision to go to Nibelheim, and Froh’s absence eventually resulted in Loge being low-key in love with Freia. This however turned out to be a showcase for Brent L. Damkier who not only proved he could sing an excellent Froh but was also a more than satisfying Loge. He isn’t what I’d call a character tenor, yet his voice fit the part perfectly. Together with his nice acting he made up for the weaknesses of the shortened libretto and his costume, which could have been way more fiery.

While he profited from the shortened libretto, Fasolt, sung by Seymur Karimov, suffered. The abridged libretto left him with not much more than two lines. One of the nicest characters in the entire opera got lost this way, together with an amazing voice. Karimov is one of the best singers Theater Regensburg has to offer. His voice and acting would have landed him Alberich, or at least a longer Fasolt if I had been in charge of casting this production.

Overall, the singers were good. An important mention is definitely Adam Krużel who has sung at Theater Regensburg for 30 years and who will now retire, after having done a fine Wotan. Singing this powerful role must be a satisfying last performance for him. The audience thanked him with lots of applause.

Being open air, the theatre obviously used micmicrophones and speakers, and sitting very close to one of the speakers, it was clearly audible for me that the sound was not coming from the orchestra and singers performing live on the other side of the water, which is why it took me a while to get into the performance. This got better during the performance and in the end I was fully invested in the musical experience, until the director decided that the best time for the finale fireworks is while the final orchestra bit is still playing. This is not only unfair towards the audience, but also towards orchestra and composer.

The rest of the production is more difficult to judge as it initially was supposed to be put on indoors. As this wasn’t possible due to corona, director Andreas Baesler had to move. Adapting a concept for a moderate sizes opera stage to the 200 meters long harbour stage is a challenge that needs to be kept in mind.

Andreas Baesler made the best of it: Following the tradition of previous open air productions he incorporated the setting into his production, for example by letting the giants sit in two cranes. However only for their first appearance, after this they walked on the ground and were the same size as anyone else.

As the audience sat far away from the stage it was hard to recognise the singers, especially ALberich, who’s costume had the same colour as the backdrop. This is why the production was supported by projections on the Stadtlagerhouse, a huge building serving as the backdrop of open air productions, created by Clemens Rudolph. While the pictures were hard to recognise at first, they helped understanding the plot after dark, by establishing the setting of the scenes and sometimes showing close-ups of singers.

The only thing I did not like about the projections was the lack of continuity regarding the Rhinemaidens, who’s singers only got on stage for the final bows, during the performance they remained in the orchestra tent.

In the final scene Rudolph projected video footage of swimmers, in the opening scene three dancers on a boat acted as the rhinemaidens, thus making the water part of the stage and allowing Alberich to actually pull the gold, a giant golden ball, out of the water. Personally, I’d appreciate it if the same characters were portrayed by the same singers. However, I understand why the decision was made: Recognizing projections in daylight is hard, and having three women dance on a small boat in the dark is dangerous.

Overall the lack of continuity is something I noticed in this production a lot. The costumes did not fit together at all. While Alberich was dressed in gray, old-looking clothes, the

giants had neon coloured suits resembling rain jackets, while the Rhinemaidens on the boat wore flapper-style dresses with fishtails underneath. It seamed like Baesler struggled to decide on a concept.

While the fireworks and the lack of continuity were off-putting, I’d still be lying if I said I did not enjoy the evening, as did the rest of the audience. The singers were good, the atmosphere nice, and it’s a pity the planned second performance had to be cancelled due to the weather – when cast, crew and audience had already arrived at the location.

5 notes

·

View notes