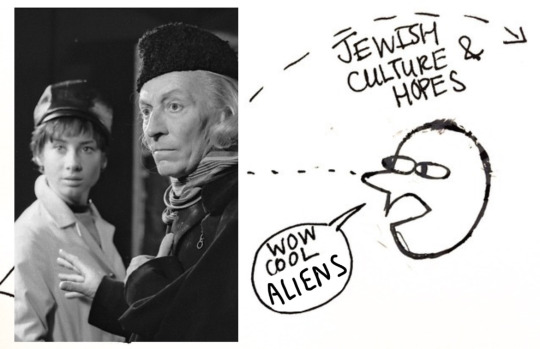

#this show was inevitably shaped by the visions of its jewish producers

Text

probably projecting but i can’t stop thinking about this. context: verity lambert and sydney newman (first co-producers of dw) were both jewish, as is carole ann ford (who played susan)

#am i imagining diaspora themes where there aren’t any? probably. is that helpful? probably not. but i digress#this show was inevitably shaped by the visions of its jewish producers#much of dw’s story involves being a stranger in a strange land - an adventurer or a refugee depending on how you look at it#i connected the dots. you didn’t connect shit. i connected them#ALSO: the original comic is by tumblr user:#millenniumitem#and it was about superman - so go check that out#doctor who#classic who#first doctor#susan foreman

174 notes

·

View notes

Link

“There’s never been a society that hasn’t had a clock running on it,” declares a character in Arthur Miller’s play The American Clock, “and you can’t help wondering – how long? How long will they stand for this?” Whether time is running out is a question on many people’s minds today on both sides of the Atlantic, whether they’re watching the “Brexit clock” tick or wondering how long the Trump presidency will endure. The American Clock is set during the 1930s but was written in 1980, as Miller watched America’s headlong race back into the gleeful, reckless greed that dominated the 1920s and led to the Great Depression, and it’s one of several of Miller’s plays that are being revived in London. Clearly that sense of timeliness, in every sense, is mounting.

In addition to The American Clock, this year will bring a new production of The Price with David Suchet to the Wyndham’s Theatre, Sally Field and Bill Pullman will star in All My Sons at the Old Vic, The Crucible will be mounted at the Yard with a female-led cast (including a woman playing the hero, John Proctor), and an almost entirely black cast will revive Death of a Salesman at the Young Vic. Miller’s plays are emblematic, representative: they are often set at moments of national crisis, whether the Depression, the Second World War or the Salem witch trials, as the conflicts of the characters symbolise epochal conflicts in American life. Read them together and you start to get a sense of a nation in a constant state of crisis.

Miller called The American Clock a “mural for theatre”, evoking the agitprop social murals of the 1930s, with a large ensemble representing all of the United States, presenting vignettes that shift and adapt across geography and time. One character picks up another’s narration, finishes another’s line. The stories are the interconnected experiences of a nation struggling to survive, as Miller attempts to render a “mythopoetic” vision of America that might be sufficient to its mythopoeic vision of itself, a nation of shared values and impulses, despite its differences.

The American Clock suggests that out of chaos can come new possibilities, an idea that many people with whom Miller would have had little sympathy are today banking on (again, in every sense). Miller rejected both socialism and fascism as too rigid and extremist; like most of his work, The American Clock suggests that a healthy society needs to find a balance between individual and collective needs. He would have had no truck with disaster socialism or disaster capitalism, but these are still possibilities the play leaves open.

Miller shows a cross-section, a collage, of Americans across the nation and the social spectrum struggling to achieve a balance between the two, in order to emerge from the catastrophe of the Depression – which Miller characterised in his autobiography, Timebends, as “only incidentally a matter of money. Rather it was a moral catastrophe, a violent revelation of the hypocrisies behind the facade of American society.” The ending of The American Clock is ambivalent about whether social renewal is possible, but understands that belief in American renewal is itself central to American renewal. Optimism becomes the only faith system that matters: hope as ideology, a communal identity defined by collective self-belief.

There are good reasons why Miller is enjoying a renaissance this year: not only was he always a political writer, but his political questions align firmly with our zeitgeist. Miller wrote about the individual’s responsibility to society – but also about society’s responsibility to the individual. He challenged the key myths of American culture, broadly incorporated in the familiar ideas of the American dream, including materialism, self-sufficiency and selfishness, but also blind faith in the lotteries of rags-to-riches stories and the redemptive individual. Miller’s work consistently turns to themes of individual and community, trying to come together to rise above chaos but often stymied by the failings of those individuals.

****

Arthur Miller was born in New York in 1915, when Harlem was a mixed neighbourhood of German, Italian and Jewish immigrants, into which black Americans were moving as they left the South in search of opportunity. His father Isidore, who had immigrated from Poland, had built up a large and prosperous clothing business, but when Arthur was 14, it all came crashing down along with Wall Street. The business failed and the family descended the economic ladder. The effects of the Depression shaped not only Miller’s adolescence but his moral and political imagination – and the rest of his life. “I don’t think America ever got over the Depression,” he later said.

Whatever the truth of that may be, certainly Arthur Miller never got over it. He chose theatre, he said, although he had little experience of it even as an audience member, because “you could talk directly to an audience and radicalise the people”. That didactic impulse never entirely left him, but it swiftly acquired greater subtlety.

Miller’s first play, The Man Who Had All the Luck, closed in 1944 after just four days. Three years later, he found his first success, All My Sons, followed two years after that by Death of a Salesman, still the play for which Miller is best known. In 1953, he produced The Crucible, using the Salem witch trials of 1692 as an analogy for the witch hunts of McCarthyist America; the hat-trick clinched his status as one of America’s major playwrights of the 20th century.

Two years later Miller himself was subpoenaed by the House Committee on Un-American Activities and publicly defied them. He had begun (improbably, it was felt) dating Marilyn Monroe, who threw the weight of her popularity behind Miller as he resisted the committee’s pressure. At a press conference he announced simultaneously that he would not co-operate and that he and Monroe were engaged. Having refused to plead the fifth amendment, which protects a witness from self-incrimination (and is thus often viewed as a morally evasive choice at best), Miller was charged with contempt of court. His marriage to Monroe was complex and controversial, and for many years after her death in 1962, continued to define his public reputation – not least because of his 1964 play After the Fall, widely condemned at the time as an exercise in self-exculpation.

But culpability was always one of Miller’s themes, to which he returned in later life as the chaos attending a highly public marriage to a movie star, followed by her early death, subsided. Themes of guilt and complicity run through most of his plays as a counterweight to myths of American innocence and optimism: people don’t just betray each other, they betray themselves and their own ideals.

Each of these great plays is driven by their protagonist’s powerful need to believe in their innocence; their acceptance of guilt and collective responsibility is tragic but redemptive – except for Willy Loman, who can never be brought to see his own self-deceptions. They destroy him, and it is left for those wrestling with his legacy to insist that “attention must be paid” to such a man. But all three men at the centre of these plays are destroyed, in different ways, by the shame they feel for their choices, by their self-righteous efforts to justify themselves and the inevitable failures of those self-justifications. This makes denial another constant theme, one that Miller watches play out on personal levels to suggest the ways it operates nationally as well.

****

The structure of a play,” Miller liked to say, “is always the story of how the birds came home to roost.” His best plays open at the beginning of aftermath: they are, from one perspective, all denouement. At the start of All My Sons, Joe Keller has already committed the betrayal – selling bad plane parts to the military – that would more traditionally have been the climax of a different play about Keller’s conflicted decisions. Here, the drama is psychological: Keller and his family must come to terms with the choices he has already made.

Similarly, in Death of a Salesman, Willy Loman has already failed: his death merely makes manifest the moral and psychological death he suffered before the action began. In The Crucible, the affair of John Proctor and Abigail Williams that provokes the dramatic action is already over when the play begins. Drama is not cause, but effect. This also gradually brings the past into the present – a technique Miller learned from Henrik Ibsen – showing that even national history is really just the history of personal choices. Climax is confrontation: confrontations with truth, with personal repercussions and moral ramifications.

Miller’s imagination ran towards the epic and the heroic, apparently insignificant lives embodying significant themes; a certain tendency towards grandiosity was usually checked by the smallness of the lives he explored. Willy Loman’s ordinariness is what makes his claims to tragic heroism in The Death of a Salesman remarkable, rather than sentimental showboating, whereas John Proctor’s place in history risks making his martyrdom in The Crucible overblown. Loman’s tragedy is that he has worked hard, and cannot understand why there have been no rewards; on the contrary, there has been only failure. Like so many Americans today who feel “left behind”, Loman is the representative American who can’t understand why the dream has passed him by.

Although The Death of a Salesman is usually read as a broadside against “the American dream”, it is attacking only a cheapened version of the dream, one that postwar America was busily selling itself: condemnation of a society allowing its aspirational political ideals to deteriorate into justifications of selfish materialism. Miller gave the play a telling subtitle: “Certain private conversations in two acts and a requiem.” It is a requiem less for Loman than for the American dream itself: the degraded dream Loman desires is the corruption of an older, more generous one – ideals of mutual responsibility and opportunity, rather than a simple, deluded faith in the idea that “free enterprise” alone could build an exemplary society. That dream is represented in the play by Willy’s neighbours, Charley and his son Bernard, whose prosperity and stability are set in relief against the Lomans’ psychological and financial precarity. Charley and Bernard represent American meritocracy, for they are also honest, hard-working and compassionate. Bernard’s profession as a lawyer reflects their sense of civic responsibility, symbolising democratic ideals of justice and equality under the law.

Loman’s profession as salesman is just as symbolic of the debased dream he chases: the empty dreams of wealth and status that were engrossing mid-century America in every sense, turning it into a nation of salesmen peddling meretricious kitsch.

The Death of a Salesman was written just as the postwar boom began, as America enjoyed a new prosperity – thanks largely to government investment in programmes such as the GI Bill, which sent millions of returning soldiers to university, and the Federal Housing Administration’s loans, which created housing opportunities like Levittown, celebrated at the time as the American dream made real.

Such government loans gave a man named Fred Trump his start in the property business during the 1940s, when he borrowed sums he was later forced to concede before a congressional inquiry had been “wildly” inflated. He used these inflated loans to develop housing projects that became the foundation of the Trump Organization, which would be sued for racial discrimination by the US Department of Justice in 1973, two years after Fred’s son Donald took over the business. The story of Death of a Salesman is that of a nation running a real risk of moral collapse – of becoming a country of con men.

The story that inspired All My Sons was true. The corruption of American ideals is Miller’s perennial subject, the failures of his “everyman” figures to live up to the values their nation espouses – and thus, by extension, the nation’s failure to do the same. The American tragedy, he suggests, is the human tragedy: the story of people who sell out in every sense.

Willy Loman cannot accept that his values were misplaced; he dies rather than face the hollowness of his own life. Both All My Sons and The Price, by contrast, are plays about living with the feeling of having sold out and the costs of the choices we make. Materialism faces off against idealism once more – but now materialism has a more cynical feel. Loman’s tragedy is less bad faith than having put his faith in a bad bargain. Walter and Victor in The Price, selling off their dead parents’ belongings, are less deluded; they are wrestling with the unintended consequences of their own ordinary choices. They gradually pull down each other’s self-righteous justifications, learning the price of being oneself, while Miller suggests the price of a society that allows its morals to be shaped by economics, for a country that offers “no respect for anything but money”.

In his autobiography, Miller wrote that he hoped the audience would leave The American Clock with “a renewed awareness of the American’s improvisational strength… In a word, the feel of the energy of a democracy.” Can energetic improvisation create a collectivity that overcomes division? It’s tempting to answer with the words of another great American writer and say that it’s pretty to think so.

But cynicism was, for Miller, part of the malaise he seeks to redress: America is not America without its idealism. That said, his dramas end with tragedy, not transcendence. And his tragic heroes are not usually hubristic; their flaws are more ordinary, more sordid. They are men who seek exculpation – but culpability, Miller suggests, is the human condition, the original sin. Character may be destiny – but character is also choice. We are what we do, we are what we choose – and this goes for the societies we create, too, while we watch and wonder if the clock is running down. ...”

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Creative Destruction and Terah’s Idol Shop - Understanding Judaism’s Approach to Capitalism and the Issue of Income Inequality

By Andrew Siegel

Economic data shows that income inequality - the gap between the richest and poorest members of society - is the highest it has ever been in the United States.[1] As the 2020 federal election cycle builds, a chorus of potential presidential candidates from the left are putting forward proposals meant to arrest the increasing capture of economic gains by those in the top 1% of American society. President Trump expectedly has characterized all such proposals as socialist. What is surprising, however (and heartening to those who believe a thoughtful dialogue on this topic is long overdue), is that many of the beneficiaries of the accelerating wealth accumulation that has occurred over the past two generations in this country are now acknowledging that something needs to change. To wit:

● Starbucks founder Howard Schultz, who Forbes estimates has a net worth of $3.7 billion, is considering running for president in order to, among other things, address what he calls a “crisis of capitalism” in the United States.[2]

● Hedge funder Ray Dalio, whose wealth Forbes estimates at $18.4 billion, released a white paper in April calling for the reform of capitalism due to its compounding positive effects for the wealthy and negative spiraling impact for the poor. Dalio says this feature of American capitalist “is creating widening income/wealth/opportunity gaps that pose existential threats to the United States.”[3]

● Private equity titan Steve Schwarzman (net worth $12.4 billion) this month outlined what he called a “Marshall Plan to address increasing income inequality in America.”[4]

● Larry Fink, whose Blackrock is the world’s largest asset manager, last year released a letter to 1,000 corporate CEOs whose stock Blackrock owns on behalf of clients. Its premise: “Around the world, frustration with years of stagnant wages, the effect of technology on jobs, and uncertainty about the future have fueled popular anger, nationalism, and xenophobia. In response, some of the world’s leading democracies have descended into wrenching political dysfunction, which has exacerbated, rather than quelled, this public frustration.”[5]

Motivation for these and similar proposals comes from a general sense of societal good (while not ignoring that a continued well-functioning American and global economy is in any case positive for the billionaire class).[6] Dalio, for instance, argues, “The best results come when there is more rather than less of: a) equal opportunity in education and in work, b) good family or family-like upbringing through the high school years, c) civilized behavior within a system that most people believe is fair, and d) free and well-regulated markets for goods, services, labor, and capital that provide incentives, savings, and financing opportunities to most people.”[7] The arguments tend naturally to be economics-based or about systemic risk, rather than grounded in principles of fundamental fairness, ethics or justice. No one has yet put forth a widely accepted deontological or teleological maxim for what we might call “conscientious capitalism” - a capitalism that does not inevitably result in 40% of the wealth in the hands of 1% of the population.[8] A worthwhile question, therefore, is what Judaism might say about capitalism, and about the current state of inequality between rich and poor that the American brand of capitalism has created.[9] Within principles of social justice that we could identify as particularistically Jewish, is remedying economic inequality an appropriate end? And if so, what could Jewish law and values contribute to defining the challenge and proposing a vision for a more economically just future?

The Torah says nothing about capitalism per se, of course - the notion of “capital” wouldn’t be named for another few millennia after revelation. Capitalism is simply the accumulation of wealth, which is then used as a resource to be combined with ideas and productivity. The output raises the standard of living of those involved in the capital-consuming project. At its heart, capitalism is about creation and how to benefit from it - and this is a subject on which the Torah has much to say. We don’t get three words into the opening line of Beresheit without it; 25 lines later, man is given dominion over the earth and all of its creatures. (Genesis 1:28-30). Later, when Abram is told by God to go forth from Haran, Abram takes with him “kol rakushim ashar rakshu” - variously translated as all the wealth he had accumulated or substance he had gathered or property he had purchased. We can safely say that Judaism and capitalism share as foundational creative acts, productivity, and accumulating value-generating resources.[10] Once Adam and Eve left Eden, human effort became a critical component of our existence; it’s assumed humans are meant to labor.[11]

Accordingly, Judaism and capitalism are not necessarily competing ideologies. From the moment Adam is forced to rub two sticks together to create fire, humans are set on a course to utilize resources, materials and our own creativity to produce and progress. Increasing nature’s yield is a basic and positive human activity, in the view of our Sages - as long as the bounty is used to lift up humankind in harmony with our better instincts. The rabbis saw the inherent duality of the human drive. They observed that we are made up of two yetzers (from the shoresh meaning to form or create) - the yetzer rah and yetzer hatov. Our yetzer hatov must always be watchful of the yetzer rah, as they are in constant interplay. R. Nachman said in R. Samuel’s name, “Can then the Evil Desire be very good? That would be extraordinary! But without the Evil Desire, however, no man would build a house, take a wife and beget children; and thus said Solomon: ‘Again, I consider all labor and all excelling in work, that is a man’s rivalry with his neighbor’.” (Bereishit Rabbah 9:9) Aware of both the promise and the challenge of that duality, Judaism is careful to subsume the human drive within its foundational ethics.

Judaism does not require that we actively seek to redistribute wealth. It does not favor the poor over the wealthy and in fact our Sages warn against doing so. Just as Moses and David rose to great heights despite laboring as shepherds at points in their respective journeys, Judaism does seem to favor social mobility. We find support for this notion of course in the famous codification by Maimonides of the levels of charity. Its highest form is the rectification of the social imbalance through upward mobility based on effort. Maimonides understood that our helping others to build their own income and wealth would become part of a larger virtuous cycle, where poverty is transformed into wealth in turn offered for the spiritual and physical well-being of the community.

Our desire to increase wealth and income must comply with three basic notions of Judaism:

God is the sole source and owner of all wealth.

Judaism establishes communal obligations.

We must walk in God’s ways.

As Jews, we are obligated to build, defend and deploy wealth only in ways appropriate under the Law. The use of our wealth and income must be in keeping with the positive (i.e. action) attributes of mercy, justice and loving-kindness.[12] According to scholar Meir Tamari, a network of halakhic rulings exist “in order to ensure that the way a man accumulates wealth is neither morally damaging nor physically harmful to his fellow men. It must also be in accordance with the norms of God-given (Torah) morality, even when these run counter to the accepted practice of the particular society in which a Jew might find himself.”[13] Jewish notions of social justice include remedying economic inequality.

As Tamari suggests, we know that Judaism is opposed to the current effects of capitalism as damaging to social justice; we find extensive guidance within Judaism for shaping a more just form of capitalism that leaves plenty of room for wealth creation and accumulation. Shmitah, peah, bikurim, gleanings and jubilee teach not only faith and trust in God’s providence[14], but are examples of the category of hefker, or ownerless-ness. See, e.g. Mishnah Peah (1-8). Because we are utterly dependent on God for our economic well-being, we must act justly in business toward others. Failure to abide causes undue hardship to others, and once this reaches systemic proportions - as we are experiencing today - causes society’s fabric to fray.

Multiple halakhot reinforce ethical behavior in the economic realm from the perspective of Jewish social justice concerns. These principles includes just weights and measures (see Leviticus 19:36), restrictions on misrepresentation (G’neivat Da’at), taking advantage of information asymmetries in the marketplace and coercion (see Baba Bathra 40b). The mishna of Baba Metzia 58b discusses the ona’a of statements in commerce, where one is prohibited from asking the price of an item if he does not have intent to purchase it, since the seller will feel mistreated and be dejected. There are extensive laws regarding the treatment of servants and workers, far too numerous to go into depth about here. As shown through these well-established concepts, Judaism provides an ethical framework that is meant to strip economic activity of its potential to create unjust or hurtful outcomes. In much of this, a common thread can be discerned.

That common thread is the important of truth-telling. We may not be silent in the face of wrongdoing or injustice. In its list of God’s commands to Moses, several of which form the basis of commercially-oriented Halakhah, Leviticus 19 contains the obligation to reprove. In a way, regardless of their positions as captains of industry, the successful capitalists now weighing in on the ill effects of America’s economic system are truth-telling. They are honoring the Torah requirement to rebuke. [15] To rebuke requires us to know right from wrong, and there is a very small series of steps from realizing the truth, to stating it, and to acting upon it, as Moses did for the daughters of Jethro (Exodus 2:16-19). Judaism requires that we speak up now about the injustices being caused by wealth and income disparity due to the separation of modern capitalism from the ethical roots established in the Torah and Halakhah.

Sociologists tell us that inside the modern corporation, managers look to each other for guidance, to demonstrate understanding of the corporate culture and to exhibit get-it-done behavior.[16] Compensation and promotions accrue to those who best demonstrate the behaviors promoted by the corporate culture. External moral norms, the link between objective goods and reward, are replaced by the need for positive reviews, which need in turn incentivizes sociability and self-promotion. As a result, learned self-rationalization eventually overtakes concepts like merit, hard work, brotherhood and common interest. The overwhelming peer pressure to achieve results or avoid failure crowds out the impulses that would, in another setting, cause one to prioritize doing the right thing. So perhaps there is an answer elsewhere, a sort of “kinder, gentler” invisible hand?

In contrast to the way his theories are today often interpreted, Adam Smith was a moralist. His 1759 work, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, is one of the foundational works of consequentialism. His economics were normative. Commercial pursuits were seen as fulfilling outlets for individual creativity, energy, productivity, resourcefulness and agency. Unfortunately, however, that sort of human capital has not led to consistent convergence of wealth within individual economies in the 200 years since the industrial revolution. There are just too many forces and actors involved. As contemporary political economist Thomas Piketty has argued, “The history of inequality is shaped by the way economic, social and political actors view what is just and what is not ... there is no natural, spontaneous process to prevent destabilizing, inegalitarian forces from prevailing permanently.”[17] Within economics itself, there is no input for the objective of securing our own well-being as well as that of our neighbor. As Mary Hirschfeld argues, economics needs an injection of both philosophy and theology if we are to overcome the atomistic definition of capitalism that permits, on rationalistic grounds, the concentration of wealth and well-being into fewer and fewer hands.[18]

Wealth inequality is one of the most pressing issues of contemporary social justice. Judaism, therefore, must confront its causes. It must challenge the conduct within American capitalism in an effort to reinsert ethical impulses and ends, regardless of whether that would demand that we hold ourselves to a standard beyond that required by law (lifnim mishurat hadin). At the same time, it is critical to remember that Judaism, within its overall boundaries, has never challenged the creative impulse in the context of trade, as a specific case. The Tanakh features many stories of self-actualization, including of our greatest prophet Moses. Judaism has no theological criticism to offer against the enrichment of individuals in the commercial sphere. What it does seek to guide is moderation of selfish impulses through consideration of our fellow human. It obligates us to conduct ourselves economically with humility due to our understanding that everything we have belongs to God and is due to God’s favor. It commits us to see the bigger picture, to seek community for the sake of peace. The tenets of Judaism can be a source of insight, which may lead, if not to solutions for this issue, then at least for thoughtful consideration of improvements in the way we think and conduct ourselves while in trade. Judaism’s ability to find room for creation, innovation and accumulation alongside ethical behavior is why it has standing to contribute guidelines for conscientious thought and action to our modern economic behavior, as our belief in one God with attributes of justice and loving-kindness has helped confront the other idols of our making since Abrahamic times.

[1] See, e.g. https://www.epi.org/productivity-pay-gap/; https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/05/opinion/what-are-capitalists-thinking.html?action=click&pgtype=Homepage&clickSource=story-heading&module=opinion-c-col-left-region®ion=opinion-c-col-left-region&WT.nav=opinion-c-col-left-region; https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2013/12/05/u-s-income-inequality-on-rise-for-decades-is-now-highest-since-1928/

[2] https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=650255208731179

[3] https://economicprinciples.org/Why-and-How-Capitalism-Needs-To-Be-Reformed/?utm_medium=adwords&utm_source=GS&utm_content=341819909261&utm_campaign=60minutes-search

[4] https://www.cnbc.com/2019/04/18/steve-schwarzman-raise-minimum-wage-eliminate-taxes-for-teachers.html

[5] https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/investor-relations/larry-fink-ceo-letter; https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/on-leadership/wp/2018/01/16/worlds-largest-money-manager-to-ceos-you-must-do-good-for-society/?utm_term=.dce24989a780

[6] For instance, Dalio’s two arguments for why the income and wealth gaps need to be closed are: “They slow our economic growth because the marginal propensity to spend of wealthy people is much less than the marginal propensity to spend of people who are short of money” and “They result in suboptimal talent development and lead to a large percentage of the population undertaking damaging activities rather than contributing activities.” In other words, we need poor people to make more because they tend to spend while rich people tend to save; and they’ll revolt unless we give them cake. OK, the last bit of paraphrasing isn’t quite fair, but it’s not far off the mark. See note 3.

[7] See note 3.

[8] https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2017/12/06/the-richest-1-percent-now-owns-more-of-the-countrys-wealth-than-at-any-time-in-the-past-50-years/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.76286d322377

[9] Harry Frankfurt takes strong issue with the idea that income or wealth inequality is a moral issue. See Frankfurt, H., “Equality as a Moral Ideal” in Ethics, Vol. 98, No. 1 ((Oct., 1987), pp. 21-22. His claim is, rather, “that what is morally important with respect to money is for everyone to have enough” - what he terms “the doctrine of sufficiency”. (p. 22) The importance of Frankfurt’s essay is in his recognition that Rawlsian ethics break down in the economic sphere, pointing out that even Rawls acknowledged that it is rational to want as much of the primary goods - rights and liberties, opportunities and powers, income and wealth - as possible. (p. 45) It is this challenge of defining “sufficiency” when it comes to wealth and income that Jewish law, and in particular certain rules governing charity, may offer a more helpful maxim than Rawls’ Original Position. God understands the psychological damage and danger to our souls from feeling “less than” (see, of course, Exodus 20:14 and also Deuteronomy 7:25). We might frame this new maxim therefore not in reference to inequality between people or nations but rather teleologically, such that “no person should have less resources than is necessary to produce the same amount of societal good as had fortune otherwise made such resources available to him or her.”

[10] In 1942 economist Joseph Schumpeter coined the phrase “creative destruction” to explain his theory of incessant product and process innovation, what he thought was the essential factor in capitalism’s growth phenomenology. One might argue that Schumpeter’s notion of ‘creative destruction” has its roots in Abram’s smashing of idols in Terah’s shop.

[11] See Siegel, S. “A Jewish View of Economic Justice” in Contemporary Jewish Ethics and Morality: a Reader, Dorff and Newman, eds. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995). Pp. 336-43.

[12] See Tamari, M. “Jewish Ethics, the State and Economic Freedom” in The Oxford Handbook of Judaism and Economics, Aaron Levine, ed., (Oxford University Press, 2010)

[13] Tamari, M. With All Your Possessions: Jewish Ethics and Economic Life. (Toby Press, 2014). p. 50

[14] See., e.g. Jeremiah 17:7: “Blessed is the man who trusts in the Lord and whose hope is the Lord.”

[15] We may assume for purposes hereof, that the individuals we cite are not breaking the Halakhah against creating a false impression of piety. We can certainly hope that their motivation is pure, rather than inserting themselves into the debate out of moral exhibitionism. As it is stated in the Talmud Bavli, Shabbat 31a, when a person is brought to judgment, the first question asked is whether he was honest in business, which is a reference to the requirement of having acted at all times - including while at derech eretz (work) - in fear of God.

[16] See, e.g., Jackall, R. Moral Mazes: The World of Corporate Managers (Twentieth Anniversary Edition). (Oxford University Press, 2010).

[17] Piketty, Thomas. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. (The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2017), pp. 27-28

[18] See Mary L. Hirschfeld, Aquinas and the Market: Toward a Humane Economy. (Harvard University Press, 2018) Professor Hirschfeld argues, among other things that the rational choices that economists presume are made in human commercial activity are devoid of ethics and virtues and therefore do not make an accommodation for non purely economic ends.

0 notes