#thirdpoliceman

Text

The sun was maturing rapidly in the east and a great heat had started to spread about the ground like a magic influence, making everything, including my own self, very beautiful and happy in a dreamy drowsy way.

—Flann O’Brien, The Thirdpoliceman

1 note

·

View note

Text

A Radio History of The Author

Flann O’Brien, Myles Na gCopaleen; Brian O’Nolan. These are a short series of archived interviews about him from RTE.

youtube

youtube

youtube

0 notes

Quote

From Twitter: Flann O'Brien would understand. @FlannOBrienSoc #ThirdPoliceman #HalfManHalfSUV #transportsofdelight— Joe Noonan (@NoonanJoe) March 1, 2019

http://twitter.com/NoonanJoe

0 notes

Text

The Third Policeman - Flann O'Brien

Not everybody knows how I killed old Phillip Mathers, smashing his jaw with my spade; but first it is better to speak of my friendship with with John Divney because it was he who first knocked old Mathers down by giving him a great blow in the neck with a special bicycle-pump which he manufactured himself out of a hollow iron bar. Divney was a strong civil man but he was lazy and idle-minded. He was personally responsible for the whole idea in the first place. It was he who told me to bring my spade. He was the one who gave the orders on the occasion and also the explanations when they were called for.

(First page, first paragraph)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Chapter 3.6 - A Dialogue on Life

Between Martin Finnucane and the narrator:

[N]...What is your objection to life?

[MF] Is it life? I would rather be without it for there is a queer small utility in it. You cannot eat it or drink it or smoke it in your pipe, it does not keep the rain out and it is a poor armful in the dark if you strip it and take it to bed with you after a night of porter when you are shivering with the red passion. {One of the few references (if not the only) to sex in the book, ed.} It is a great mistake and a thing better done without, like bed-jars and foreign bacon . . .

[N] That is a nice way to be talking on this grand lively day when the sun is roaring in the sky and sending great tidings into our weary bones.

[MF] . . . Or feather-beds, or bread manufactured with powerful steam machinery. Is it life you say?

[Joe] Explain the difficulty of life yet stressing its essential sweetness and desirability.

[N, to Joe] What sweetness?

[Joe] Flowers in the spring, the glory and fulfillment of human life, bird-song at evening--you know very well what I mean.

[N, to Joe] I am not so sure about the sweetness all the same. [To MF] It is hard to get the right shape of it or to define life at all but if you identify life with enjoyment I am told there is a better brand of it at the cities than in the country parts and there is said to be a very superior brand of it to be had in certain parts of France. Did you ever notice that cats have a lot of it in them when they are quite juveniles?

[MF] Is it life? Many a man has spent a hundred years trying to get the dimensions of it and when he understands it at last and entertains a certain pattern of it in his head, by the hokey [Holy Spirit?] he takes to his bed and dies! He dies like a poisoned sheepdog. There is nothing so dangerous, you can’t smoke it, nobody will give you tuppence-halfpenny for the half of it and it kills you in the wind-up. It is a queer contraption, very dangerous, a certain death-trap. Life?

{Indeed.}

0 notes

Text

Chapter 3.4 - The Captain of All the One-Legged Men

So far in Chapter 3, the narrator has been traveling from Mathers’s house, heading to the police barracks in an effort to get the cash box. He notices he is totally unfamiliar with the stunningly beautiful countryside around him, despite it being near his home. He also begins to remember his life, including the murder, but can’t remember his name. He imagines names that might be his, including Signor Beniamino Bari & Dr. Solway Garr, whose stories during a night at La Scala we hear through the narrator’s imagination. He then sets on about his journey.

The narrator begins to get sleepy (this happens a lot in the book) and lies down in a ditch. When he awakens, he is being overlooked by a very menacing character, a robber who will be revealed to be Martin Finnucane, “the captain of all the one-legged men in the country.” (p. 47.) Before he reveals himself to be a robber, the narrator tries to guess his occupation:

Bird-catcher

Tinker

Man on a journey

Fiddler

A man out after rabbits

A travelling man with a job of journey-work

Driving a steam thrashing-mill

Tin plates

Town clerk

Water-works inspector

With pills for sick horses

Farmer

Publican’s assistant

Something in the drapery line

Actor

Mummer [18-19th century English mime popular at Christmastime]

0 notes

Text

Chapter 3.3 - Horror at La Scala

We are treated in this chapter to more detail about Sr. Bari, the eminent tenor. We hear tell of out-and-out riots, met by bayonet charges no less, outside the opera house of La Scala, in Milan, when it is announced that there is no more standing room remaining for Sr. Bari’s rendition of Puccini’s La Boheme. Tens of thousands of Bari fans rush the entrance. Scores are hurt, including a silly-named Constable, Peter Coutts (strange name for an ostensibly Italian policeman). 79 are killed!

This chaos is nearly matched by the “delirium” inside as Bari hits a high-C note in singing the aria Che Gelida Manina:

When he reached the high C where heaven and earth seem married in one great climax of exaltation, the audience arose in its seats and cheered as one man, showering hats, programmes, and chocolate-boxes on the great artist.

(p. 41) Quite the show. Mention is made of this aria, “What a cold little hand,” being the favorite of [Enrico] Caruso. There may be a clue here as to the time of the setting of TPP as well: Caruso first recorded Che Gelida Manina in 1906. While the recording is not referred too, it could be inferred that the novel is set after 1906 because it isn’t certain otherwise how the narrator would have been familiar with Caruso’s rendition of the aria except by hearing a recording.

This fantasy appears to be the narrator’s ego projecting itself as the great Bari, as noted by Joe:

A bit overdone, perhaps, but it is only a hint of the pretensions and vanity that you inwardly permit yourself.

And that is not all! We are next told of Dr. Solway Garr, possibly in the audience at Sr. Bari’s ultimate performance. He gallantly saves the life of a fainted duchess who turned out to have a denture in her thorax. Dr. Garr is hailed as a hero. He refuses ten thousand guineas from the duke, tearing the check “to atoms.” The crowd, in appreciation, bursts impromptu into a rendition of ‘O Peace Be Thine’ (a song I don’t know of) and Dr. Garr demurs. Quite the hero.

As the narrator says to himself after this tall tale, “I think that is quite enough.”

0 notes

Text

Chapter 3.2 - Paging Mr. Freund

Hugh Murray; Constantine Petrie; Peter Small; Signor Beniamino Bari; The Honourable Alex O’Brannigan, Bart.; Kurt Freund; Mr. John P. de Salis, M.A.; Dr[.] Solway Garr; Bonaparte Gosworth; Legs O’Hagan.

These are the names the author imagines might be his once he realizes he’s forgotten his name, though he remembers his life. Why is there no period after the “Dr” before Solway Garr? Typo? I don’t know. The other names I like very much.

Legs O’Hagan, in particular, sounds like he would be a cowardly Irish mobster who got his nickname by being the worst lookout ever, running away at even the slightest provocation.

Interestingly, Kurt Freund, whose name appears in the above list, was a “real-life” sex researcher who used measurements of blood flow to the penis to diagnose a wide variety of sexual . . . uh, proclivities, conditions, preconditions, preferences, orientations . . . whatever. Anyway, his research became the basis for the decriminalization of homsexuality in Czecholoslavakia in 1961 and in other countries later, though at first it was used to bar homosexuals from military service and to otherwise discriminate and punish. Based on his evidence, however, he eventually advocated that homosexuality was innate and not “curable.” He met resistance to these views but is widely revered today as an early advocate for LGBT rights. That said, his work has been criticized on all sides, whether for providing too easy a tool for discrimination, or for excusing perversion, or for just being general quackery. So, whether right or wrong, he can’t be said to be a politico or a crusader for either “side.”

More controversially, though, he also waded into the finer details of human sexuality by writing about and studying various “philias” that remain criminal, or that are, at least, politically questionable. His preference to diagnose rather than to condemn certain “turn-ons,” including that of active resistance by the sexual partner, remain highly controversial because they are said to turn criminal acts into diagnosable, inculpable conditions.

More interestingly still, in the late-1960s, when TPP was published, Mr. Freund’s earliest works, which first began to be published in 1958, would have been well known to those (as, say, journalists and civil servants such as the author) who could have easily accessed it. So let’s assume O’Nolan knew of Freund and his work and talked about it, maybe surreptitiously, to his colleagues. But TTP was written in 1939-40, before Freund had published anything, so if this reference is to the Kurt Freund, it would have had to have been added by the author to his manuscript for TTP much later than when it was originally written. That may seem unlikely, but it is also unlikely that the author just happened to coincidentally put a name as rare as Kurt Freund into his book. We will likely never know for certain, so let’s assume the author did intend to refer to the Kurt Freund...

Well, the author and his wife never had children despite 18 years of marriage. The author was raised in an oppressive sexual universe of Ireland in the 1920s. Little is known about his personal life.

Further there are details such as this in TPP:

‘Women I have no interest in at all,’ I said smiling.

‘A fiddle is a better thing for diversion.’ [Martin Finnucane]

(p. 47) This and other similar quotes from TPP could have just been in-character asides. But, is it not just as possible that the author was gay and was referencing Mr. Freund here because his work could be said to have normalized homosexuality at a time when it was condemned? Was the mention of Freund a signal to gay peers, or to himself? I don’t think the wider public would have been aware of Mr. Freund’s work until much later if at all, and such a one-off reference could have easily gone unnoticed. And perhaps that was the point. To make it obscure and unnoticeable to the point of deniability.

Obviously, I can’t say definitively, and I am not trying to fall into a lazy, “everyone is gay”-type of “edgy” criticism. But I know there is precious little sex in TPP. There is also a strange co-sleeping arrangement between the narrator and Divney. There are also a few quotes, such as the above, which tend to be very dismissive of women, not just generally, but in terms of attractiveness and sexuality in particular.

What’s more, in mulling this all over, you could consider the epically heterosexual and promiscuous life of many authors in the same era as Mr. O’Nolan, in contrast to the author’s own decidedly unremarked-upon personal sexual life, all in light of the mention of Mr. Freund and the other factors above, and decide for yourself whether these all carry with them any allusions as to the proclivities of Mr. O’Nolan in the sexual arena.

Or, you could consider that he could have just been a practicing Catholic, even if not a devout one, or even a lapsed one, who did not (or only very rarely and regrettably) practiced fornication, and who happened to have had to deal with infertility on the part of himself or his wife. He may also have been an alcoholic, which can carry with it its own obstacles to sex and procreation.

Still though, the mention of Kurt Freund is a bit strange and possibly telling.

A final note about Freund. He was a Czech Jew who married a non-Jewish Czech woman. They divorced in 1943 to protect his wife, Anna, and their daughter, Helen, from persecution by then-Czechoslovakian occupiers under anti-Jewish and anti-miscegenation laws. They remarried after the war and had a son. What a tragic and beautiful story. Also, Mr. Freund’s parents and brother were killed in the Holocaust. It is easy to forget how easy many of us have it today.

0 notes

Text

Chapter 2.3 - Gaunt Gossamer Gowns

Their colloquy on “no” ends with the narrator trying to get Mathers to disclose the location of the cash box or give it to him using the “do you refuse trick.” Mathers refuses because the narrator no longer knows his name. As such, Mathers could not get a receipt to show who he gave the cash box to. The author is troubled by forgetting his name, but thinks he can always pick anyone he wants. He has a brief interior monologue about Signor Bari, and then he and Mathers move on to a dialogue about gowns.

Mathers posits that everyone is given a gown at birth by the policemen and another on each birthday. The subsequent gowns are worn on top of the others, stretching as the wearer grows, and residing beneath the rest of the wearer’s habiliments like Mormon undies. These gossamer garments vary in color depending on the direction of the wind at the recipient’s birth, but are so faintly colored as to be almost imperceptibly fine. Nonetheless, the darker the original tone, the sooner the later layers become totally opaque, at which time the wearer dies. So the lighter the original color, yellow, say, the longer you will live. Brown or maroon and you’re heading for an early grave. And you can see it coming with each new layer of under-garb.

This talk of lightly-colored robes is faintly interesting, but despite reflection, I don’t see the point besides folly. It is a fantastical and absurd notion, but doesn’t tie in to anything later in the novel. These digressions are not uncommon in TTP and I don’t begrudge this passage, except that it is not really funny either. Just strange. Were the book ever filmed, I could see this exchange being omitted except visually, with glimpses of the narrator’s robes, progressively darker, throughout the story. Perhaps the policemen would be shown sewing them.

Or maybe this digression on wind and lightly-dyed gowns is a background story for a larger, never completed sequel or series of related books. It could provide color (so to speak) for a Third Policeman universe to be developed by Netflix or SyFy. I would love to see such a thing, with shows and movies about the narrator, the policemen, a young Mathers, Finnucane and his men, and all the rest of this terrifying splendor, but I fear I and anyone else who dared watch it would shortly be driven to suicide to escape the torment.

De Selbyiana

Some notes: This is where De Selby’s most famous theory, that of night as an accumulation of dark air, is first mentioned. (p. 32, n. 4) In that same footnote, oddly, De Selby’s work, A Memoir of Garcia, is first cited, but it short form (”Garcia”) as if it had been cited before. The work is cited in full for the first time six pages later. (Ch. III, p. 38, n.2) Whether this was an editing error, brought about by moving some footnotes around without revising them to ensure the full cite is made first and short cites only thereafter, or whether this is a purposeful gesture by the author as a nod to the absurdity and nihilism of TTP is unkown. I know as a former lawyer, that forgetting to correct short cites is very common when editing a brief under a deadline. You move the text with the first reference to a point after a subsequent short cite, or vice versa, and then when first reference is made, the reader doesn’t know what work you’re referring to. It is a pretty bad mistake because it is difficult for the reader to go ahead to try to find the full cite. But is also an easy mistake to make because editing for the propriety of short cites and long cites is a time consuming job often left until the end of editing and then often forgotten about.

In footnote 4 on page 32, we also see reference to a second commentary on De Selby from La Fournier, Homme ou Dieu (Man or God), the title of which refers, ridiculously, to De Selby.

At the end of this exchange, Mathers tells the narrator that the police barracks is nearby, and identifies the policemen as Pluck, MacCruiskeen, and Fox (disappeared for 25 years). The narrator announces his intention to visit the police barracks, but decides to sleep at Mathers’s house for the night first because the sun has gone down during the conversation--gone down, BACK THE SAME WAY AS IT HAD COME UP!!! Spooky!

The narrator also plans to complain to the police about the theft of an American gold watch of his--a lie he suspects may be responsible for the bad things that happen to him thereafter. And probably this is true. After all, if you’re in Purgatory for a murder, should you really double down on the lying? Oh well, we’re all in for it now.

0 notes

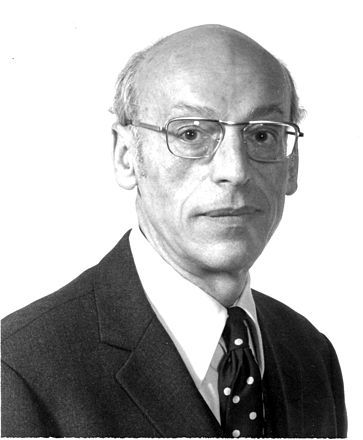

Photo

The name is Bari. Signor Bari, the eminent tenor. Five hundred thousand people crowded the great piazza when the great artist appeared on the balcony of St. Peter’s Rome. - (p. 31)

This is a great aside in the book. One of a few times when the author just drops in apropos-of-nothing mentions of sui generis characters who never again appear in the book. It seems like Joe mentions them, though it is not clear. Simple, fanciful, ephemeral descriptions. Like someone you met in a dream and remembered only once thereafter. Perhaps they are just momentary flights of fancy by the author, but I like imagining these characters. Bari is pictured here in an illustration from De Selby’s Golden Hours.

0 notes

Text

Chapter 2.2 - No and Thou Shalt Not

Spoiler: The narrator is killed by a booby-trap mine planted by Divney in lieu of the cash box. He then sees Mathers, sittting in a maroon dressing gown, bandaged about the face and neck (from the jellying the narrator delivered) with a tea set and oil lamp on a small table next to him.

After steeling himself, the author gets into a negatory-heavy back and forth with Mathers wherein Mathers explains that he led a sinful life and upon reflection had decided that the best way to avoid sin was to say no to everything, especially every offer or suggestion, whether from others or from within himself, including every question the narrator had been asking. (pp. 27-31)

Saying no to everything could be taken as a comedic reflection of the self-denial incumbent in Christianity, most prevalently in its monastic expression. The author would have been exposed to western monasticism growing up in the thoroughly Catholic Ireland of the 1920s. This would have included his school days at Blackrock College, which was founded by French Spiritans, formerly the Holy Ghost Fathers, though this is a spiritual congregation (with priests and lay brothers) and not a monastic order. Nonetheless, O’Nolan, like nearly all Irish of his time, would have witnessed around him many nuns, brothers, priests, and monks who had undertaken vows of poverty or other forms of “saying no” to the offers of the world around them, for asceticism, while being viewed somewhat skeptically in Western Christianity (Peter King, Western Monasticism, 33 (Cistercian Pubs., 1999)), nonetheless is featured in at least some aspects of all Catholic religious and clerical life. He would also have carried with him his own Catholic catechesis of self-denial as virtue.

Saying no to everything is actually also a pretty good strategy for avoiding sin. This makes sense because the universe of bad or sinful things one can indulge in is much larger than the world of good things one can do that can bring one closer to God. After all, eight of the Ten Commandments, say what not to do.

I am the Lord your God . . . You shall have no other gods before me. This has to be the only commandment that’s gotten easier to keep in modern times. There are just not as many other gods competing for your worshipping these days. Jehovah and Allah? Same God, in theory. Hindu pantheon? Couldn’t say much about it other than lots of arms; not really grabbing me. Buddha? Not a god. Shinto? That’s just folding paper animals. Thor? Marvel fans and Norwegian metal heads. Amun-Ra? Thanks for the founding myths, but no more pharaohs. Greco-Roman pantheon? Mostly planets, as it turns out. In the classical Mediterranean, this one might have been tough, what with the wide variety of sincerely-believed in gods around and the prevalent pantheism and so forth. But now? I got this one. . . . Unless you mean figurative gods, such that money, or booze, or certain videos that could become “gods” before God to me if I were greedy, or gluttonous, or lustful. Then that could get sticky. But those are their own sins (see below) and if this commandment covered those, it would render them superfluous which is against a cardinal rule of statutory construction. So this one is basically aimed at idolatry and mishy-mashy, let’s be Christian, but also Muslim or whatever too-ism. I’m on pretty solid footing here.

You shall not take the name of the Lord your God in vain. I slip up on this one a lot, but with some practice, following this one is very doable. It’s clear, unequivocal, and sets a pretty low bar, honestly. Thanks a lot, God. (That wasn’t sarcastic. Still, was that vain? I hope not. Otherwise, I’m off to a bad start.)

Remember the Sabbath and keep it Holy. There’s a lot more temptation here than there used to be (there’s always been some gray area, too, for “essential” professions and those with work reports due on Monday).

Still, keeping this commandment is not a cakewalk. For starters, everyplace but that weird, locally-owned appliance store and Chick-Fil-A is open until at least 6 on Sunday in an effort to compete with Amazon, so shopping is tempting on Sundays. Dining out is too. For starters, I’d recommend the Avocado Egg Rolls at Kona Grill. No one has ever told me shopping or dining out are no-nos on Sunday, but you are making the employees work to serve you and its not exactly essential, except the Avocado Egg Rolls--you have to try them.

Also, in today’s economy it’s a lot more likely you might have to work on Sunday even if you’re not a nurse or a quarterback. Fighting your Sunday work schedule with the religion excuse is pretty tough for most people who aren’t Amish or something as it’s usually greeted with a look that conveys, “What, you think you’re going to Heaven and I’m not, church boy?” or “Well, you’ll have plenty of time to go to church when you’re fired. Long live Ayn Rand and Mammon!”

Luckily, I don’t have to work Sundays, so I’m good here.

Honor your father and your mother. Love you guys. Once you’re out of this house and financially independent, this one is a lot easier. Don’t hold a grudge. Respect their shit. I got this one . . . Wait, this gets a little more complicated for Catholics, with all the extending of it to siblings and society and raising your own kids right and what not. Still though, I think I can get this one. Just have to be diligent.

Thou Shalt Not Kill. You’d think this is easy! But, not so fast. This also includes not injuring yourself by abuse of food, alcohol, drugs, and the like. Now, as a married parent of a newborn who spends all day at home, this one is a lot easier than it used to be, but its one you really have to watch out for in this era of low alcohol and drug prices, oversized entrees, and the cocktail renaissance (“I’m not an alcoholic, I’m a tastemaker and a chemist!”).

You shall not commit adultery. Oh boy. I knew we were going to get to this one. Well, you knew it was going to come up eventually, so to speak. This one is tough. No doubt about it. It includes basically everything you’ve ever thought about doing that you don’t talk about in front of your mom that’s not included in Cmdt. 5. Essentially, if it is not sex inside marriage with no impediment to pregnancy, you’ve run afoul of this one. Also, it gets a little touchy on the homosexuality front in today’s political and civil rights climate.

But remember, while you have to try, you get infinity second chances through confession . . . if you’re contrite. I know what you might be thinking, “But I’m not sure how contrite I’ll be tomorrow. And there’s so much temptation! Women’s Health today is basically Playboy from thirty years ago! And the tanning, forget about it. And the bras. And the shorts. And the INTERNET!!!! People sixty years ago or more had it much easier. They had to seek out temptation and they still failed all the time on Commandment 6. And you expect me to comply in the age of 4GLTE and incognito browser windows?”

To that I say, draw some solace in the Didache, the oldest of Christian instruction manuals, dating to the first century: “For if indeed thou art able to bear the whole yoke of the Lord thou shalt be perfect; but if thou art not able, do what thou canst.” Probably the most helpful advice ever given. I wish it was advertised a little more. So, good luck with this. I’d recommend getting married ASAP. Moving on.

Thou shall not steal. OK, we’re breathing a little easier now after the double-whammy of 5 & 6. Keep in mind though, that this includes a lot of economic stuff, like not paying an unlivable wage, price manipulation to get advantage on the harm of others, corruption, appropriation of the public goods for personal interests, work poorly carried out, tax avoidance, counterfeiting of checks or any means of payment, any forms of copyright infringement and piracy, and extravagance. So just remember, being a slack-ass piece of shit at work is stealing too. And, on the flip side of the coin, so is being a hard-ass, greedy owner/boss.

You shall not bear false witness against your neighbor. This commandment covers a lot of ground about just not being a bad person. In addition to outright perjury, this bad boy covers rash judgments and presumptions, disclosure of another’s faults without reason (detraction), calumny, gossip, flattery, bragging, boasting, etc. But if you can avoid talking shit about others, lying, and bragging about yourself, you should be OK here for the most part. There’s also a lot of ways to venially violate this commandment (e.g., white lies), unlike with six. So even if you mess up here, just pray about it. You won’t get caught in a state of mortal sin if the Second Coming happens before confession on Saturday (whether this Saturday or the last one before Holy Week next year, whenever you might go). OK, so don’t talk shit about people. Got it. We’re almost there, and the last two are basically one!

You shall not covet your neighbor's house . . . wife . . . or anything that is your neighbor's. This one is pretty tricky because it covers internal dispositions of covetousness of the flesh. So, basically lust. I feel like this one is there just to really hammer home that you should try to keep your mind pure, not just your body. But obviously, impure sexual thoughts is one of the most difficult of the sins to keep at bay, so it seems a little onerous to have this commandment on top of “Big Six.”

Maybe there’s another reason for it, though. Maybe it’s here to serve as a tax evasion charge that the U.S. attorney hits a criminal with when they can’t prove the extortion racket. Or the constitutionally dubious sodomy charge when they can’t quite prove the rape, or the false imprisonment, or Mann Act violation. “What’s that? You say you didn’t actually have sex with her. You were just over at here house, eh? Well, guess what? NINTH COMMANDMENT, buddy! We saw you looking at her at the bar. Listen, you can plea this out to coveting now, but if you want to go to trial we’re going for lust, adultery, the whole smear. You’re lucky we came in when we did.” OK, so there’s been some good and some bad so far, but only one to go.

You shall not covet your neighbor's house . . . wife . . . or anything that is your neighbor's. (Wait, what?) This one takes much the same language of Cmdt. 9 and focuses on the coveting of material goods, not the flesh. So this one covers greed and envy, primarily. This can be hard for some to keep, I’m sure. Keeping up with the Joneses is a national pastime after all. But just don’t be greedy, be happy with what you have, and you should be OK. There, you did it! Even if you didn’t keep all the commandments, you tried. Now go to confession.

So other than remembering the Sabbath and honoring your mother and father, and going to church on Sundays, there’s not much else you have to do. In fact it’s the doing that gets you into trouble: doing drugs, doing “it,” etc. In fact, if you said no to everything but what you had to do to stay alive (like Mathers), kept the Sabbath, honored mom and dad, and went to Church on Sunday, I’d say you’d have a guaranteed ticket to Heaven. You wouldn’t even have to go to confession because you wouldn’t have done or failed to do anything you had to do or not do.

So with so many more things to say no too than to say yes to, if you are looking to lead a holy life in a Catholic worldview, as Mathers is in the novel, it is wholly logical for him to conclude that the best way to redeem himself from his sinful life is to say no to everything.

This being a darkly comic novel, however, both Mathers and the author quickly discover a Jesuitical workaround to Mathers’s principle of prohibition. The narrator will just start questions with, “Do you refuse to tell me...?” Then Mathers will say no, and answer the question. Ta da! Mathers slyly admits that he’s okay with this sidestep:

So if you ever hear someone offer a priest a drink by saying, “Father, would you turn down a glass of whiskey?” you now know what’s going on.

0 notes

Photo

One of De Selby’s wall-less houses, from the County Album. Pretty solid-seeming, actually, apart from the tarpaulins.

0 notes

Text

Chapter 2.1 - De Selby on Houses

At the outset of Chapter II, the author expounds directly about De Selby’s theories for the first time. In particular, his views on residential architecture are discussed. These views are best exemplified in illustrations in De Selby’s Country Album of two types of houses: one with a roof and walls of loose tarpaulins that roll down from the gutters around large doors and windows, and another with one wall facing the prevailing wind and tarpaulins providing the remaining structure including the roof. These homes are built on masonry but surrounded by latrines.

You see, De Selby blames houses and living indoors generally for mankinds current softness and dissolution, so it seems he wants to make shelter as thin and rudimentary as possible.

It is presumed these designs for houses are risible, but they actually would not be so bad in the right climate. In southern Greece or other Mediterranean climes, perhaps southern California or Chile, such houses would probably suffice as shelter, provided the tarpaulins could be made taught and were opaque.

But in De Selby’s drawings, the tarps are loose and flowing, making the houses resemble “a foundered sailing-ship.” (p. 21) Thus, it is clear that De Selby’s tent-houses would scarcely be shelter at all in northern Europe, whence he and his critics hail. (To say nothing of the ill health-effects of the latrine moats surrounding his houses.) Accordingly, we see a common view of De Selby in which he is hailed as a genius but nearly all his ideas are explained as unfortunate examples of momentarily lapses of his geniusness.

This may seem a familiar human tendency, for example, in politics:

President Trump is a compassionate guy, it just so happens that everything he says evidences a complete lack of compassion or sympathy, for reasons not under his control and against which he has no defense.

Or, in defending your best friend to your wife:

Honey, I know Dan got arrested for disorderly conduct at our wedding, and did cocaine at our reception, and has huge gambling debts, and is unemployed, and dumped his last girlfriend for no reason after eight years, and may have possibly stolen some stuff last time he stayed here, but deep down, he’s really a good guy.

And so in this case, where De Selby’s genius is evidenced in the fact that he apparently has legions of intellectuals devoting their lives to analyzing and chronicling everything he ever wrote and did, while spending much of that effort explaining why most all of those writings and doings were not actually spectacularly wrong or insane. It’s absurd and quite funny. And the humor of it only grows as the author delves further into De Selbyiana throughout the book, and the inanity of De Selby and his commentators is taken to even greater extremes.

We are introduced here to the first of De Selby’s comentators by name, La Fournier, a French intellectual whose work on De Selby is entitled L’Engime de l'Occident. He attributes the “regrettable lapse” of De Selby’s work on houses to his having later discovered his own doodles and then sought to explain them in a way that accounted for his estimation of his own genius. (pp. 21-22)

0 notes

Text

Chapter 1.9 - The Aftermath

There is not a lot to be said about the aftermath of the murder, but a few details from earlier in the story are made more clear. First, the narrator specifies that he was inseparable from Divney after the murder for three years before he retrieves Mathers’s cash box. (p. 18) That would make him 27 when the murder occurred, as he said he was about 30 at the time they had been known to be inseparable and he began to explain why. (p. 12)

Second, the narrator explains that the physical intimacy between he and Divney was imposed by the narrator in an effort to make Divney so uncomfortable that he would relent to the narrator’s demands to give up the cash box. Although explained, this is still a little hard to believe, even in this context, without more insight into the narrator’s psyche, which isn’t really given. So while I thoroughly enjoy this introduction to the story, in all its weirdness and color, it does require a little too much of a leap.

The narrator ends up having to bury Mathers nearly entirely by himself because Divney ducks out (probably to hide the cash box) while the narrator is pummeling Mathers’s head. Divney finally returns and, after a funny line about the narrator thinking Divney left to attend to a call of nature, they finish the job together.

The narrator starts to ask about the cash box on their ride home and frequently thereafter. Divney won’t tell him where it is until the heat is off. The narrator doesn’t believe there’s any heat because no one misses Mathers, who travels frequently.

We get a window into Divney’s true nature when he laughs uncontrollably after recounting their line to distract Mathers, “Would that be your parcel on the road?” It is the second most disturbing thing in the story so far, after the murder.

After three years of the narrator not letting Divney out of his sight, and after the narrator's starting to even carry a pistol, Divney finally agrees that things have quieted down and says he will go get the cash box.

“We will get the box,” he says. Divney gives a hurt look. But I think that’s only because he realizes now that he’s going to have to kill the narrator. I think his plan was to tell the narrator he was going to get the box and then disappear, probably to Cloankilty.

To carry out his plan to kill the narrator, Divney slyly convinces the narrator to get the cash box by himself–a little reverse psychology. He convinces the narrator that it would be “just” for the narrator to get the box alone since Divney had withheld it for so long. I can actually see how this might work because it ostensibly shows some trust on Divney’s part. Or it would show trust if Divney’s weren't actually going to murder the narrator too. I suppose the narrator is just too trusting, but it could also be taken as naivete to the point of idiocy. The narrator does suspect that Divney might use the time when the narrator goes to get the box to go get the box himself, but this doesn't make a lot of sense after three years. In either case, I can overlook the lack of believability here because the author wouldn’t want to give away or make too obvious at this point that the narrator is going to die.

The duo later walk to Mathers’s house, and the narrator agrees to go get the cash box inside under the floorboards because Divney will never be out of his sight, as he stays leaning against a stone wall across the road.

The author goes into the house, saying with much forboding that he doesn’t even know his own name.

0 notes

Text

Chapter 1.8 - A Remorseless Bludgeoning of a Defenseless Old Man on a Deserted Country Road

It sounds a little worse when it is made clear, doesn’t it? The murder of Mathers is described in a few short paragraphs on page 16 of the book. Though it is not described in elaborate detail, the raw brutality of the crime is jarring:

Damn.

Yet again, it is hard to understand how the narrator, an otherwise mild-mannered armchair intellectual with a passion for an obscure polymath named De Selby, is not only talked into a murder by a lazy bartender, but how he has what it takes to brutally smash the victim’s skull with a spade, stopping only due to fatigue. Mathers head must have been reduced to a paste. It really is shocking as a crime, described in a cold, real, detail that seems even more jarring in the context of an otherwise cartoonish book. But this only makes it harder to understand the narrator and his psyche in any real sense.

0 notes

Text

Chapter 1.7 - Motive

In a flashback to explain why he never left Divney’s side for several years--the murder and Divney’s refusal to give the narrator the proceeds of the concomitant robbery. This is explained to have occurred “several years” before, but well after the Wrastler was introduced at the pub, when the narrator was about 24. So, the murder of Mathers would seem to have occurred when the author was probably 26 or 27.

At that time, the narrator explains that Divney started reading “or pretending to read” the narrator’s exhaustive, collated index on De Selby and his commentators. Divney effusively praises the book, saying that the narrator could make a fortune in royalties. He encourages him to “put it out.” The narrator demurs, explaining that an unknown like him would have to self-publish, at great personal expense. (That sounds familiar!)

Divney then again laments that the farm is losing money for lack of fertilizer, caused, according to Divney, by the “Jewmen and Freemasons.” The author knows this is not true, yet he says nothing.

Again, this is pretty hard to understand. Why wouldn’t the narrator just say, “You know what, Divney? You are full of shit. You have been lying to me for years. Where do you get the money for these suits? Also, you are robbing the customers! I want a full accounting of this farm’s and the pub’s expenses and your personal funds or I am going to charge you with embezzlement. Also, get the fuck out of here.” The only explanations offered are that he is physically afraid of Divney (though besides robbing passed out customers, Divney is never indicated to be physically violent, yet the author is missing a leg) and/or that the narrator is so obsessed with De Selby that he needs Divney to work the farm and pub so the narrator can spend all his time studying the great De Selby. Since Divney is probably the only person to be found who would do this job for free beer and food, it does put the author in a bind. But enough of a bind to agree to a murder? It’s hard to grasp.

Divney mentions that they should see about getting some money for the narrator to publish his book on De Selby, and also some for Divney so he can marry a woman named Pegeen Meers. Several days later (the long con) Divney, mentions Mathers, letting the narrator figure out that he doesn’t intend to borrow from Mathers or ask him for charity. This process takes another six months, but which point the robbery and murder of Mathers has slowly crept into the daily conversation of Divney and the narrator. You have to admire Divney’s deviousness and patience in carrying out this master plan of his. Indeed, I would have enjoyed reading more about Divney’s long con.

Three months more, and the narrator had agreed to the plan. Three months more again and he tells Divney he has put aside any misgivings. That is a full year that Divney works on the narrator to get him to carry out this plan, and this on top of the years of nagging about the finances of the farm and pub--all of which may have been laying the groundwork for the narrator’s involvement in the murder. In retrospect, it is terrifying how Divney convinces the narrator to carry out the crime with him so subtly and over such a long period of time.

I cannot recount the tricks and wiles he used to win me to his side. - p. 15

Fuckin’ A.

The main trick appears to be flattery.

It is sufficient to say that he read portions of my ‘De Selby Index’ (or pretended to) and discussed with me afterwards the serious responsibility of any person who declined by mere reason of personal whim to give the ‘Index’ to the world.

So Divney gets the narrator to commit murder by appealing to his pride. A deadly sin indeed.

0 notes