#these are rough but these are also where I peak with art its all downhill from here

Text

I'm sketching Jay moments for an idea I had

#ninjago#ninjago jay#jay walker#yes I like snake jay so ofc I'm giving him fangs#he deserves to keep at least some snake traits#these are rough but these are also where I peak with art its all downhill from here

269 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Is She Real?” and Other Distant Dreams within Dreams: Fifteen Films Which Are Completely Their Own Thing

There are films which stick to one’s mind due to their greatness as well as those which do the same for their extreme inferiority. Mediocre films have a tendency to leave one’s mind like an uneventful day once the night falls. Then there are films which one keeps coming back to because they are completely their own thing. These are films which stay in memory due to their striking originality. They might be masterpieces, and thus greatness could be among the explanans for the phenomenon of preservation, but they do not have to be. In terms of quality or personal preference, these films might be somewhere in the middle. They elude the nightfall of oblivion on other grounds. Although their survival of the test of time can thus be explained by reference to uniqueness, it should be emphasized that uniqueness in this case does not mean any conventional weirdness or doing the extraordinary. The notion I am interested here is not what you might call in-your-face uniqueness (feel free to insert a list of contemporary “indie” directors). Rather, I am interested in the unique unique. I am talking about films which stay with you, but you can’t really point your finger at them and say why; they stay with you not because of quirkiness, of artistic mastery, of historical significance, of intricate story or peculiar characters, but because of an utterly original approach to cinematic discourse -- which might, of course, include all of these to altering degrees. Such originality might be less obvious, but it is there, it is real, and it is singular.

The following list of fifteen unique films will not include the obvious candidates from the first films which did this or that to the weird-for-the-sake-of-being-weird adventures. I have tried to resist the urge to go where the fence is lowest and make a list of “weird movies”; instead I have tried to focus on a more subtle notion of uniqueness. The challenge as well as the allure of list-making are the constant limitations one sets for oneself. That is also the reason why no director pops up twice in the list. Another yardstick for a unique film of this kind is that the film in question cannot really be compared to anything else. Or if it can, the comparison remains loose at best. Hence the absence of films from auteurs whose bodies of work form distinct unique wholes but precisely as wholes, not singular parts. Jean-Luc Godard, Jean-Pierre Melville, Robert Bresson, Douglas Sirk, Howard Hawks, Yasujiro Ozu, Jean Rouch, Michelangelo Antonioni, you name it. All of them managed to craft an original cinematic discourse, but they developed the execution of that discourse in countless films that form an admirable whole of aesthetic consistency.

So, here, I am not interested in cultural peculiarity, a director’s originality, or uniqueness within a genre. I am interested in a slightly different kind of personality with regard to cinematic discourse. Although each of the following fifteen films exemplifying this unique uniqueness obviously belong to a director’s oeuvre, I believe that all of them stick out in one way or another. They have not been listed in order of personal preference or quality but in terms of uniqueness (which is, of course, a notion difficult to define, and which is a notion not completely free from personal preference and quality, I’m sure). As such, they tell another story, perhaps unique by nature, about the enigma of the seventh art.

15. Cria cuervos (1976, Carlos Saura, SPAIN)

It is an indescribable delight to witness Carlos Saura’s magnum opus Cria cuervos (1976) unfold before you for the very first time. Since the film, which tells the story about a young girl and her two sisters who try to cope with growing up after the death of their parents, was released one year after Francisco Franco’s death, it has become something of a standard interpretation to watch Cria cuervos as an allegorical tale of "the children of Spain” coping with the loss of their patriarchal leader in a new social reality. Yet any serious spectator will tell you that this is just one side of the film’s multi-layered coin of meanings. Its ambiguous structure might tie in with the prevalent narrative tendencies of Saura’s generation of left-wing Spanish directors, but it also works as a metaphor for the vague human mind. Not only cutting but also panning between the present, the past, and an imagined future, the film unfolds as a poignant story about loss and longing, the desire to be somewhere else, something else, some other time. One of the best films about childhood ever made, Cria cuervos denies romantic innocence without falling into the trap of naive pessimism. It embraces childhood as a part of being human, being mortal, being without something, being toward loss, being as always losing something.

The most famous scene from the film -- and an example of just this -- is definitely the scene where the young girl, played by the unforgettable Ana Torrent, listens to a pop song “Porque te vas” by Jeanette, a nostalgic love song about leaving that reminds the girl of her mother’s death. A touching moment beyond words that can only happen in the cinema, this scene exemplifies beautifully the tendency of children to cling onto seemingly insignificant objects that they will carry with them for the rest of their lives. The images where the girl quietly moves her lips in synchronization with the song are breath-taking and heart-breaking. The way how Saura executes this brief scene, in one sequence shot, is just so original, so inimitable, and so Saura. The emotions are not clearly visible on the child’s face, most likely because she is unable to understand let alone express them, but they come from another place that lies somewhere in between of sound and image. The context for this scene is her frustration with her aunt, who she briefly impersonates (”turn down the music”), which further pushes the obvious meanings and the obvious feelings outside. Maybe it is just a random pop song? What is left is the ambiguity of meaning and feeling. And that resonates. Powerfully. I have never seen anything quite like it. These are unique images which speak loudly about the power of cinema. Some might say that what makes Cria cuervos as unique as it is are Ana Torrent’s dark button eyes, but, in reality, it is how Saura frames them, how he lights them, and how he cuts from them. Cria cuervos has no single detail which would exhaust Saura’s style; yet his sense of composition, his choice of shot scale, his sense of color, sound, and movement are in every second of the film; they are characterized by the subtlest nuances which distinguish an ordinary beautiful object from a true work of art.

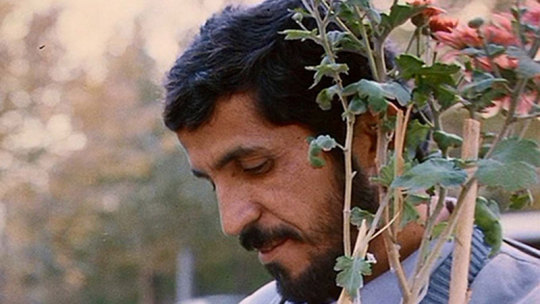

14. Nema-ye Nazdik (1990, Abbas Kiarostami, IRAN)

Abbas Kiarostami’s penchant for meta-cinematic discourse, which addresses enduring human themes through postmodern questioning of the possibilities of representation, reaches a peak in Nema-ye Nazdik (1990, Close-Up). Based on true events, it tells the peculiar story about a poor Iranian man, Hossain Sabzian (played by himself, like all the performers in the film) who pretended to be the famous Iranian director Mohsen Makhmalbaf for the Ahankas, an upper-class Iranian family to whom Sabzian told that he wanted to use them and their house for his next film. When Sabzian’s hoax was revealed, the Ahankha family sued him only to drop charges after Sabzian’s intentions proved out to be more complex than those of a traditional impostor. Kiarostami mixes documentary footage with staged scenes of what happened to the extent that it is impossible for the spectator to make a distinction. Not because of slyness, or Kiarostami’s talent to cover his tracks, but precisely because the distinction disappears: when the people involved are placed in front of the camera, acting out what has happened in the not-so-distant past, there is no longer a sense of staging but of being.

In a marvelous moment of poetic intuition and cinematic genius, Kiarostami’s camera picks up an empty spray can rolling downhill on asphalt. In the spirit of the “phenomenological realism” of the Italian neorealists, Kiarostami’s objets trouvés, like the empty spray can, are not symbols for something else. It might be juicy to see meaning written in the code of the empty spray can, say, in terms of the looming void behind the roles we all play, but Kiarostami’s camera uncovers it as a mere abandoned tool. Heidegger would call it Vorhanden, a being present-at-hand, whose factual existence is obvious to us after it has lost its functional purpose in its appropriate context, its primordial being as Zuhanden, a being ready-to-hand that one surrounds oneself with in the everyday reality of practical life. Even if this coarsely rolling empty spray can was the postmodern alternative to Sisyphus’ rock, it would be more a metonymy than a metaphor. It is a desolate, cast-off tool whose lonely mundane being paradoxically charms us in its banality. It is, what we might call in the spirit of anticipation, the taste of cherry.

Here, in the peculiar zone between metaphor and metonomy, meaning and the lack of it (or independent meaning), inhabited by empty spray cans, lies the uniqueness of Nema-ye Nazdik. There is nothing holy or sacred in Kiarostami’s images. The material density of the rough texture of the depicted reality drains from them. The close-ups of the film -- whether in actual shot scale or in narrative intimacy achieved by precisely restrictive framing and extensive use of the off-screen space -- startle us with this banality of the facticity of being and the phenomenal surface of reality. The final close-up of the film shows us Sabzian, looking down, holding a bouquet at the gate of the Ahanka residence where Makhmalbaf has taken him to make amends. One senses the Chaplinesque tragedy of life in close-up. It is tragic because there is no comfort from contextualization; there is a factual detail thrown at us in its strange existential disclosure. A rolling empty spray can or a structured identity at ruins -- revealed, stripped, naked. The human theme of longing coalesces with the meta-cinematic theme of the possibility of representation as one feels the unquenchable thirst for escape, the yearning to be someone else in this banal world of objects-at-present. Where else in the cinema does one find all of this?

13. The Wrong Man (1956, Alfred Hitchcock, USA)

Although Hitchcock is definitely a genre director, meaning that he really devoted his whole career to the genre of suspense (whether in thriller, horror, espionage, or adventure), he made a lot of films which pushed the limits of genre aesthetics, conventional narration, and classical style toward unexplored territories in the land of film. Hitchcock’s legacy is in fact constituted precisely by his relentless desire to look for new ways of cinematic expression. The most obvious example would probably be the “trilogy” in which Hitchcock tested -- and, perhaps to popular opinion, failed -- the slow aesthetics of the long take: Rope (1948), Under Capricorn (1949), and Stage Fright (1950). Their uniqueness is admirable, and the two latter border on masterpiece, but the most unique of Hitchcock’s films is, I believe, The Wrong Man (1956).

If Hitchcock, the great manipulator of his audience whose “buttons” he loved to push, is placed in the group of directors who mastered formalist montage over realist mise-en-scène, following a heavily Bazinian distinction, we might conclude that The Wrong Man is the closest Hitchcock ever got to cinematic realism. Although the film does manipulate the spectator, guiding their gaze throughout rather than giving them the freedom of deep focus and multiplanar composition (the cardinal virtues of Bazin’s theory), its austere mise-en-scène, economic narration, and minimalist editing make it Hitchcock’s most Bressonian film. Interestingly enough, and this will bring us to the film’s uniqueness in a moment, Hitchcock’s biggest fan and André Bazin’s most famous disciple, François Truffaut first expressed great appreciation for The Wrong Man when it came out and later disowned the film in his famous interview book with Hitchcock [1].

The passage where Truffaut challenges Hitchcock, not in order to humiliate him but in order to get him to defend his artistic choices, is among the best parts of the whole interview book. Their discussion concerns the scene where the protagonist, played by Henry Fonda, is taken to his prison cell where he does not belong to because he really has not committed the crime he is being accused of committing. There is no dialogue or voice-over narration to tell us what the character is going through, but Hitchcock’s cinematic narration still visually focalizes into his internal, first-person point of view, while switching to an external, non-focalized third-person perspective in medium shots of the character in captivity. Hitchcock cuts between these medium close-ups of the character’s face as he is looking at something and point of view shots of the austere cell that serves as the object of his gaze. There is no music, no sound -- just stark images of a narrow, grey space. The calm cutting between these two types of shots manages to reflect the character’s inner life which becomes, so to speak, externalized by cinematic means. It is as though his mind extended to the space whose austerity became to articulate his experience of imprisonment, isolation, and, ultimately, loss of self. The non-subjective space turns subjective; its concrete features start to channel the character’s mental states in ways which contemporary directors like Lucrecia Martel have mastered.

The problem Truffaut has with the scene is its ending. The scene concludes with a medium shot where the protagonist leans against the wall of his cell, eyes closed, distraught, powerless. Suddenly, non-diegetic music starts playing on the soundtrack and the camera begins swirling in a circular loop around the character. As the movement of the camera accelerates, the music intensifies and finally reaches a crescendo coinciding with a fade-to-black to the next scene. Truffaut disliked this shot because it seemed to break with the Bressonian asceticism that Hitchcock had been practicing prior to it. It is also noteworthy to add that never again is there anything like this in the rest of the film (and thus the shot does break against the norm of consistency): The Wrong Man returns to its minimalist, Bressonian roots, letting go of the striking expressivity of such camera movement (which is not used to follow a character or reveal further details of narrative significance in the diegetic space). One might recall, for example, the unforgettable shot which dissolves the praying protagonist’s face with the “right man’s” face, and what a completely different feel that shot has to it -- it is something Bresson would never do, but it is something the Bressonian side of Hitchcock does.

Despite Truffaut’s challenge, Hitchcock refused to defend his film, disappointingly noticing that it was not that important to him. That might be the case, but it might also be that Hitchcock was not sure of his artistic choice, or he didn’t know how to explain his intuition, or he didn’t want to argue about such matters. Maybe he thought he had failed in his experiment. Either way, it is this moment which always gets me. It feels a little awkward, and it always pushes me just a little away from the film, to a strange borderline zone of cringe -- but, at the same time, it feels wonderful. It’s the moment where one can so clearly see Hitchcock’s legacy as an innovator and a re-generator, looking for new ways to make films -- and not always with success. It’s the moment when you realize that you are not watching Un condamné à mort s’est échappé (1956, A Man Escaped) but The Wrong Man. It goes against the realist style which avoids blatant and outspoken expression, but it goes so well with Hitchcock’s own style where a sudden cut to an extreme long shot from an extreme high-angle on the top of the United Nations building is completely natural. It’s also one of those moments, definitely alongside the great dissolve of the two faces, where one can sense the presence of cinematic uniqueness. Although I think Un condamné à mort s’est échappé is a better film, there is really nothing like The Wrong Man. From Hitchcock’s startling opening monologue to the inexplicable happy end, bordering on Sirkian irony, The Wrong Man is really its own idiosyncratic thing.

12. Lola Montès (1955, Max Ophüls, FRANCE)

Master director Max Ophüls’ final film and cinematic legacy Lola Montès (1955) is the definitive cult film. It’s strange, it’s wild, and its off-the-rails uniqueness made it a massive flop. It’s the stuff that dreams are made of... the dreams in cult film land. A lavishly told story about a woman with hundreds of lovers, who is now presented to us as a circus attraction, did not resonate with contemporary audiences. With the exception of the new film critics of Cahiers du Cinéma, who were to define the cinema of the following decade, everybody hated the film. To those who understood the magic, however, it was wonderful. To those who still do, it is beyond divine. The combination of box-office and critical failure with a huge budget and an unprecedented desire to challenge convention from the 50-year-old director, who was soon to pass away, turned Ophüls into a martyr figure for the new generation of French filmmakers. Like Orson Welles, Ophüls was -- to them in their own land -- a misunderstood genius, a maestro who died two years after the release of his final film that found too few kindred spirits.

What makes the case of Ophüls’ martyrdom so fascinating is the fact that on paper Lola Montès sounds like everything Truffaut et co. hated. It is based on a novel, its script has other writers in addition to Ophüls, it has an all-star cast (and without the obvious choice, the Ophüls favorite of the 50′s, Danielle Darrieux!), and it has lavish production values backed by a big budget. Does this not sound like le cinéma de qualité par excellence?

The fact that Lola Montès sounds like dull quality cinema on paper, however, does not mean that it looks like it on celluloid. And that’s what makes it unique. Known for his penchant for sumptuously elaborate camera movement (to the extent that a camera which is not moving on tracks simply looks naked in the Ophüls universe), Ophüls went an extra mile to make his forward-tracking dolly shots work in a wide circus arena without revealing the tracks. Resonating with the width of the diegetic space and the volume brought to it by such cinematography, Ophüls also widened his film into color and the CinemaScope aspect ratio for the first time in his career. Unlike anyone prior to him and few after, during a time when CinemaScope had not been around for longer than two years, Ophüls made the unexpected decision to play with the aspect ratio. For most of the screen time, we see the events unfold in 2.55:1, but, every now and then, when mood or character identification so requires, Ophüls narrows the aspect ratio back to the Academy ratio by placing curtains on both sides of the lens. The peculiar technique of altering the aspect ratio within shots in itself is enough to make Lola Montès unique, but the way it connects to the theme of the theater -- not only as the circus milieu but also as the publicization of the private sphere -- and the surprising yet accurate (which never feel too much on-the-nose) choices Ophüls makes in using it turn Lola Montès into a bizarre marvel.

11. Daisy Kenyon (1947, Otto Preminger, USA)

On paper, again, Otto Preminger’s Daisy Kenyon (1947) seems like nothing but a love triangle done to death. Joan Crawford plays a woman who is having an affair with a married man, played by the impeccable Dana Andrews, but in the middle of their troubled affair -- that would suffice to constitute a love triangle -- enters a returning war veteran, played by Henry Fonda (the only actor to appear twice on this list!), who also catches the woman’s eye. The film unfolds as a series of moments which push the female protagonist to the embrace of one man or the other. What makes the film so unique, however, is its original cinematic discourse, its use of style and narration. In his admirably insightful new book on 40′s Hollywood, Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling (2018), professor of film studies, David Bordwell calls Daisy Kenyon “one of the most psychologically opaque films of 1940′s” [2]. Preminger’s cinematic narration is characteristically restrictive of narrative information. There is no voice-over, which would provide the spectator information about the characters’ inner motivations and feelings, but this is only made more ambiguous by the dialogue where the characters keep making contradictory statements about themselves and others. It is difficult to keep track of their mood swings as well as their cognitive discontinuities, and make any cohesive conception of their true motivations and feelings. This was yet to become the dominant characteristic of modern European cinema (mainly Antonioni, above all), but here it blends with classical Hollywood.

The film is filled with strange moments of peculiar, recurring pauses in dialogue which enhance an ambiguity that starts to feel bigger than the characters and their petty worries. Fonda’s character suddenly ends a moment of conversation with Crawford’s by saying “my wife’s dead” without receiving a response of any kind from his romantic interlocutor. Similarly, he nonchalantly proclaims his love to her -- “I love you” -- but gets no response in another passing moment of indifferent quietude. There are no typical responses nor are there typical initiatives. There are only words that try to grab onto something but most often miss their targets that perhaps never even existed.

The lack of conventional non-diegetic music, the use of deep-focus cinematography, deep space compositions, and lingering shots create a mood of emptiness and despair, which reflect a deeper difficulty in expressing oneself. This theme is articulated on the formal level of style and narration, but it also becomes knitted into the story world toward the end when the courtroom sequence plays with the ideas of illogical human behavior and the impossibilities of finding out what people have done and felt. When one of the two men and the Crawford character embrace one another in the film's final shot, it is equally impossible for the spectator to believe that this is the stable, happy end of a typical Hollywood romance. It is merely another dumbfounded pause, another pointless initiative, another unnoticed response, which will soon be followed by quietude, distance, and alienation.

10. Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975, Peter Weir, AUSTRALIA)

Australian director Peter Weir has made a lot of weak films (I am not a fan of the sentimental Dead Poets Society [1989] or the pseudo-intellectual The Truman Show [1998] -- though I do have a little thing for Fearless [1993]), but his breakthrough film, based on the novel by Joan Lindsay, Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) is a real treat. A fictional account of the disappearance of three schoolgirls and their teacher during an all-girls boarding school’s picnic on St. Valentine’s Day in 1900, Picnic at Hanging Rock begins with a quasi-documentary opening text and concludes with an extra-diegetic voice-over discussing the case, making it seem as if the story was true. More than fooling the audience, this device guides them into another world, where something like this might have happened, and into the hypnotic trance of a mystery, all of which is enhanced, of course, by the first images of a foggy landscape and the girl’s words in voice-over:

What we see and what we seem are but a dream, a dream within a dream.

Weir’s greatest film leaves a lasting impression with its unique, impressionist aesthetics of pale colors, quiet sounds, soft focus, lush cinematography, eerie panpipes music, and an often strictly limited field of focus. It is as if the film had been shot through lace or a veil, giving the effect of the faded fantasy image of the romantic belle époque. The final jaded slow-motion shots of the group before the disappearance have an otherworldly quality. They bear a resemblance to impressionist paintings, but the jaded pace of the visual stream of the images emphasizes their mechanic artificiality as though these were paintings made with the first motion picture cameras. Weir’s narrative structure is likewise closer to poetry or painting than to prose as the focalization of the narration is constantly switching, the characters remain a mystery with their inner world and their psychological motives left completely in the dark, the relations between the diegetic events are vague to say the least, and Weir cuts between them in an unconventional fashion. It is nothing short of cinematic uniqueness which stays with the spectator for the rest of their life. One of the most sensitive and clever mystery films of all time, Picnic at Hanging Rock keeps astonishing with its whimsical combination of mystery and reportage, impressionism and mystique, the fantastical and the real.

9. A Canterbury Tale (1944, Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger, UK)

Made in the days of Capra’s wartime propaganda series Why We Fight (1942-1945), whose patriotic spirit spread across the Atlantic to films calling for Anglo-American solidarity, Powell and Pressburger’s A Canterbury Tale (1944) defies tired cliches and patriotic sentiments in its utterly unique rhythm and tone. Taking Chaucer’s classic as an inter-textual framework, A Canterbury Tale focuses on three characters who, on their way to Canterbury, stop at a small village where a mysterious “glue-man” is terrorizing young women who dare to date soldiers. In contrast to most of the wartime productions of the time, Powell and Pressburger’s film turns its gaze from the grandiose to the minuscule, a small village that is unafraid to show its quirky silliness but as such grows into a metaphor for western civilization.

One of the famous director duo’s biggest critical and commercial flops, A Canterbury Tale defies easy classifications. What makes the film unique in a timeless sense lies in its tone and rhythm that are hard to describe. The set-up could mark the beginning of a frivolous farce, and the film is definitely not lost on moments of genuine hilarity, but, as a whole, A Canterbury Tale develops toward the area of peculiar pathos, humanistic tenderness, and profound melancholy. The mythic and the mundane, the romantic and the realist, the everyday and the sublime, the eternal and the transient all find their strange fusion in the film’s rendez-vous of distinct tones, moods, and ideas. Classical studio artificiality gets mixed with on-location authenticity, which is characterized by historical uniqueness as the contemporary spectator realizes that these places are no longer there, creating a tone like no other. In terms of rhythm, the film is always flowing without a hurry, yet never too slowly to announce itself as different or weird. The film’s uniqueness seems so simple, encapsulated in the smallest of things (the co-presence of the past and the present, the smell of the countryside that is imagined through the images, the allure of the any-space-whatevers), but it is so difficult to describe let alone achieve. It must be seen to be believed...

8. Dong (1998, Tsai Ming-Liang, TAIWAN)

The late 1990′s attracted some filmmakers to imagine eschatological scenarios and project them on the big screen. The approaching arrival of the new millennium generated visions of both anxiety and hope, but man’s relentless tendency toward end-of-the-world nightmares drew him closer to the former. These cinematic efforts on the brink of the new millennium usually vary between downright awful (Armageddon, 1998; End of Days, 1999) and surprisingly tolerable (12 Monkeys, 1995), but Taiwanese director Tsai Ming-Liang’s -- who had made a reputation for himself with the understated tale of eroticism Ai qing wan sui(1994, Vive L’Amour), whose final shot in itself might earn its own prize of uniqueness -- Dong (1998, The Hole) shows not only genuine originality and imagination before new times but also a unique tonal combination of both emotions associated with the historic transition: fear and hope.

These emotions are tied together in the film’s thematic nexus of encountering something new, a theme that is treated by Ming-Liang appropriately in an utterly novel fashion. The story takes place in a block of flats in the semi-urban outskirts of a Taiwanese city where people live in quarantine due to the lack of clean water, a problem that has some dire consequences, fitting for the new millennium: without water, people turn into cockroach-like entities that crawl in the dark spaces of moist dirt and dry trash. Two people, a man and a woman, who try to survive in this situation, are united when a hole appears on the man’s floor (being the woman’s roof) due to plumbing renovations. This hole, which is both physical and emotional -- concrete to the point that we can sense its material urgency and abstract to the point that words are not enough to express it -- begins to generate unprecedented intimacy between the two. The characters rarely communicate. At best, they might yell at each other when the woman, the neighbor beneath, finds her ceiling leaking. But there is a more tender connection, one that cannot be expressed by them. In a stroke of charming genius, Ming-Liang uses 50′s-style musical sequences, where well-dressed characters sing Grace Chang’s songs and perform dance numbers that convey the introverted characters silent feelings in a manner that obfuscates more than it clarifies (there is no aha-moment tailored for the spectator). As these musical sequences take place in the same desolate urban spaces where the characters exist, Ming-Liang’s realist aesthetics of the long take, deep space compositions, and a detailed naturalist mise-en-scène of faded colors and flickering lights are challenged by romantic artifice. The space, which turns into its own character, starts dreaming. It dreams of becoming something else, somewhere else, far and away, safe from the arrival of the new.

As the world prepares for never-before-seen destruction, the holes in the characters’ souls become tangible in the form of a narrow gap, not only the grey chasm between the two apartments but also the distinction between these two diegetic dimensions (the world of song and the world of silence). As the new both anxiety-inducing and hope-awakening millennium approaches, the two characters encounter love, something they had not expected, something they had forgotten, something that appears in a totally unprecedented form -- to them as well as to us, the audience. This unique story provides us with an interlude to reflect. Where are we going? New times are coming. We can always look back to the past. We can find solace in its embrace. What is collapsing? What can be recovered? What will the abyss of the hole engulf? And what will it bring about in times of chaos? A new connection, a new intimacy, a new cinema?

7. Herz aus Glas (1976, Werner Herzog, GERMANY)

Shot mainly in director Werner Herzog’s home environment of Bavaria, accompanied with gorgeous landscape shots from all over the world which still merge with the same central milieu, as well as Popol Vuh’s score, Swiss yodeling, and medieval music, Herz aus Glas (1976, Heart of Glass) is the shining ruby in Herzog’s prolific yet familiar oeuvre. Although Herzog is often celebrated as an eccentric filmmaker whose cinema constitutes an entirely unique thing of its own, his films are usually quite clearly connected to one another, and one knows what to expect from them (which is also a compliment to Herzog’s auteur caliber). Herz aus Glas, however, brings a breath of fresh air into a catalog that already seems to be as fresh as fresh can be. It is definitely the film that sticks out. No other Herzog film employs his unquenchable desire to pursue new profound images as strongly and startlingly.

The story concerns a Bavarian town in late 18th century whose main source of income comes from blowing a rare type of ruby glass. When the secret of the ruby glass passes away with the town’s deceased master, a prophetic seer from the hills descends to the townspeople and foresees their destruction. To anyone who has seen the film, it is quite clear that the story is secondary to the film’s strange, private discourse which might be better left unanalyzed since its mere verbal description seems to aggregate an insult at worst and a failure at best.

While there are certainly more than one factor which explain the film’s incomparable uniqueness (the presence of seemingly unrelated landscape shots as an additional level of discourse, the ambiguous story as well as its elusive structure, the extremely stylized mise-en-scène that creates a sense of alienation and distance), the raison d’être for the film’s reputation obviously derives from Herzog’s exceptional decision to shoot the whole film with the actors under hypnosis. Consequently, the film is rife with images of hypnotized people who stare very attentively at something in the off-screen space -- something, an object, a sight, an event, something that remains a mystery to the hopelessly unaware spectator. In the physical space, the actors are obviously looking at something Herzog the hypnotist has guided them to look at, but in the diegetic space, the characters are looking with great attention and focus on their pre-determined doom. Their focus is startling because, despite their attentiveness, they do nothing but walk towards their demise. This works because, though pre-determined, their doom is indeterminate in the sense that they cannot really make any sense out of it. A stroke of genius on Herzog’s part, this heavily stylized acting turns into a metaphorical framework for a community which is under collective hypnosis heading out to the horizon of destruction with a sense of blind determination.

The film is totally alienated from classical story-telling, and many of its scenes take place in spaces which we might see only once and whose relations to the rest of the spaces remain unclear. Mapmakers of fictive worlds, beware. They are places which Herzog remembers from his childhood, or places which he has imagined for his past or future. There are many elements which would annoy the regular movie-goer from the slowly developing cry of a woman as she witnesses two seemingly dead men on the ground to the inexplicable bursts of laughter from the old man. There are plenty of scenes which seem to serve no clear purpose. There is a scene where a painting falls from the wall behind a man after which he tries to lift it, fails, and then returns to his original posture as if nothing had happened. There is also a sequence shot of a glassblower making a glass horse out of the melt matter. This scene has no obvious meaning in the film, nor should it; the shot is just there. It is there for us to marvel at it and to reflect on the beauty of craftsmanship, the art of glassblowing.

If the quest of Herzog’s cinema is to always look for new images, then Herz aus Glas delivers more than any of his films. One of the many peculiarities of the film are the recurring landscape shots from all over the world which remind one of Herzog’s brilliant documentary Fata Morgana (1971). These landscapes might be the visions of the attentively looking townspeople or not. As such, they might be images of destruction, of the end, or of the beginning -- or not. They might be an imagined landscape of origins. My personal favorite is the shot, which has been done mechanically by a frame-by-frame technique, of a river of clouds on the top of a forest. There is an enchanting mystique to this hypnotic image. When we look at it, we might think that it is about something, but we should not make the mistake of trying to explain what that something is. Nor should we find an external point of reference to call it a metaphor for something else. We should embrace its mere cinematic aboutness.

6. The Quiet Man (1952, John Ford, USA)

John Ford, the man who made westerns, is to modern America what Homer is to ancient Greece. Beyond the genre of lonely travelers in the wild west, Ford took his cinematic myth-making to other worlds. They Were Expendable (1944) provided the first signs of Ford’s unadorned and unsung sensitivities beyond the desert, which, after initial opposition, he was able to appreciate (sort of) after Lindsay Anderson pressed him on the emotional depth of the film in his celebrated interview book. The real deal when it comes to Ford’s hidden personality, his artistic ambition, and his aesthetic sensitivity, however, is The Quiet Man (1952), a film like no other if there ever was one. It is a unique, poetic fable of pastoral idyll, understated modern anxieties, battling dialectics of reality and fantasy.

A classical love story where a man, Sean Thornton, played by Ford soulmate John Wayne, returns to Ireland from America where he falls in love with Mary, played by Maureen O’Hara, The Quiet Man is like an idyllic postcard, a tale of the fantastical countryside that is presented in an overly romanticized fashion. Its humor, varying between masculine slapstick and battle-of-the-sexes screwball comedy, would make the advocates of the me-too era cringe. However, I believe that Peter von Bagh was right in seeing the film as greater than life. To him, its scenes of love carry “metaphysical might.” [3] There is more to them than the eye can see. When Sean pulls Mary away from the door opened by ferocious wind to kiss her for the first time, there is a sense of baroque awe as Mary’s hems bend against her rigid legs in a gust of divine wind. Perhaps telling of its uniqueness, the film’s closest kindred spirit seems to be a film that looks totally different, Murnau’s Sunrise (1927), which carries similar “metaphysical might.”

The Quiet Man was not received well during its initial release. Its fable-like illusions threw away all hopes of Ford’s return to the realist cinema of Hollywood he helped establish in the late 30′s and early 40′s. The far landscapes of the wild west were replaced by a postcard idyllic Irish village of Inisfree where trains are late, chores can be put on a halt to chit-chat, and traditions persevere. From the beginning locus amoreus of a boat by lakeside at dusk to pastoral iconography of a redhead shepherding sheep, a priest fooling fish, and drunkards playing the accordion, The Quiet Man is Irish pastoral of 50′s American optimism. Despite the film’s idyllic nature and the romantic mise-en-scène that gives birth to it, one would be making the mistake if one concluded that The Quiet Man was completely lost on realism. “Inisfree is far from heaven, Mr. Thornton!,” reminds one character. It is rather that in it Ford manages to find a totally unique combination of realism and romanticism, the modern and the traditional, the American and the Irish, in a fashion that reminds me of Brontë’s Wuthering Heights (1847). Sean escapes America, the land of freedom and opportunities, to his home country of Ireland. Although never stated explicitly in the film, one can see a social undertone, as noticed by von Bagh: during the Korean War, which was still going on, disillusions scattered throughout America. Inisfree’s distance from heaven might be lost on Sean’s nostalgic eyes, but he seems to imply something about the looming vicinity of realism to us when, upon seeing Mary for the first time, his yet undiscovered love interest and wife-to-be, he states: “is she real?”

It is, in fact, this scene, this first encounter between the lovers-to-be, that always gets me. Its uniqueness escapes words. The scene begins with a long full shot of Mary amid sheep, which is motivated as Sean’s point of view shot as the scene progresses. There is a cut to a low-angle medium shot of Mary, which is followed by a reverse shot of Sean and then another low-angle medium shot of Mary, as she slowly vanishes beyond the frames of the screen space. A return to the long full shot of Mary amid sheep is followed by a medium shot of Sean. Dumbfounded, amazed, looking afar, and hopelessly in love, he says: “Is she real?” Ford’s brilliant choices in montage and shot scale articulate the distance between the characters, which will be a recurring theme in the film -- “There’ll be no locks or bolts between us, Mary Kate!” -- while also bringing them in close intimacy that still remains a mystery to both of them. There is a heavenly feeling to all of this. Where are we? The modern Sean, escaping the disillusions of 50′s American optimism, might be asking himself: “Is this -- Inisfree -- real?” We, the viewers, we, the lovers of the film, we, the lovers of cinema, might be asking ourselves: “Is this -- The Quiet Man -- real?”

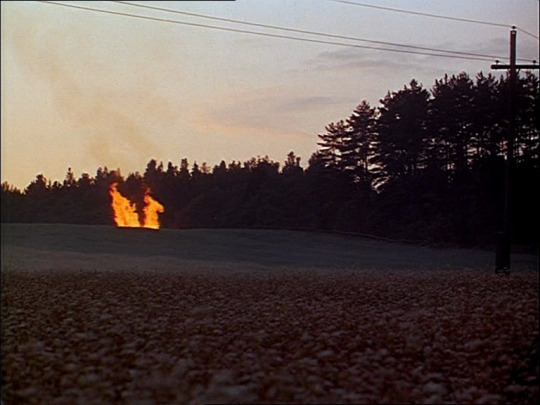

5. Tini zabutykh predkiv (1964, Sergei Parajanov, USSR/UKRAINE)

Ukraine-born director, Sergei Parajanov’s breakthrough film Tini zabutykh predkiv (1964, Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors) is on fire. It is on fire like a mixture of jazz and opera, a blend of ancient epic and modernist poem, a mishmash of waltz and jitterbug that never, for some odd unfathomable reason, feels haphazard. It feels eternal, timeless, and archaic, but, at the same time, contemporary and modern. The truly marvelous thing about all this is the fact that the story itself is a fairly traditional love story. Ivan and Marichka, whose families are rivals by heart, fall in love at a young age. After Marichka drowns in an accident, Ivan falls into depression but then remarries. In his new life of work and dull everyday chores, he is tormented by the memory of his first love. In the end, he dies either due to a hit from a sorcerer, who has made passes at Ivan’s new wife, or due to his incurable loneliness in a void universe without love.

Such a classical romantic tale acquires an unprecedented energy from Parajanov’s cinematography that is characteristically free and mobile -- in stark contrast to that of Sayat Nova (1969, The Color of Pomegranates), the director’s best-known film. The handheld camera is always on the move. It does not shake in the sense that the contemporary spectator has become accustomed to identify “handheld camerawork;” in fact, it can be very steady at times, but it moves quickly and ferociously. It pans so fast from one place to another that the eye does not register the spaces between the two steady screen spaces before and after the pan. It can appear to be fixed on a spot, but then it starts gliding or flying as in the amazing shot of Ivan lying on the large raft on the river. Watching the film unfold on the big screen is like having your head dislocated in some strange non-physical sense. One might think that such energy is distracting and makes one pay too much attention to the cinematography. The effect, however, is the opposite. It’s hypnotic. Everything feels intuitive and natural. One simply feels bewildered before this film to the extent that one starts imagining new images to the film. It is as if the camera found freedom and was liberated from its physical ties, becoming a disembodied eye whose movements are impossible to be predicted. The spectator never knows where the camera is going to move next, what the next angle will be, or in which scale the next shot shall be.

As such, the camera turns into a lyrical speaker of a poem or a stream-of-consciousness narrator of prose who identifies with the characters’ experience that cannot be accessed unambiguously. The most obvious example is not surprisingly the use of point of view shot when Ivan’s father is axed to death: red blood fills the screen, which is followed by a strange image of red silhouettes of running horses. Less obviously subjectivized stylistic decisions, where the camera identifies with characters’ experience, include the beginning scene where there is a “point of view shot” from a falling tree’s perspective, which is followed by a hypnotic spin of the camera as though it detached from material reality after a character dies under the tree. During the first embrace of Ivan and Marichka, Parajanov’s camera keeps the characters in focus and in a tight medium close-up, but the intimacy is complicated by implied visual distance: the use of the telephoto lens coalesces multiple layers of tree branches and other flora as a soft, flat veil enfolding the lovers in their natural innocence as the camera encircles them in eternity. When Ivan falls into depression after Marichka’s death, not only are the colors replaced by a surprising shift to black-and-white but also the movement of the camera becomes significantly calmer and slower. When Ivan starts feeling the presence of the dead Marichka -- as a ghost, as a memory -- there is a series of jump cuts showing Marichka behind Ivan’s window, rather than a return to the previous stylistic program. All of these exemplify cinema’s ability to subjectivize without the use of point of view shot or voice-over. Parajanov realizes this potentiality beautifully and uses different cinematic means without restriction but never without a consistent vision.

There are shadows from the past which obstruct Ivan and Marichka’s innocent love, but there are also shadows from the new past which prevent Ivan from moving on with his life. In an unforgettable scene that is still unparalleled in film history, Marichka’s ghost entices the delirious Ivan, recently struck by the sorcerer, to death in a wintry forest. Both characters move toward each other, but they do not seem to be walking in the medium shots that only show their heads moving against the background of the white forest as their voices sing a song of love without their lips moving. There is a strange sense of movement and ceased time. There is a touching sense of the wonderful yet painful grip of love. There it is, unshadowed, unforgotten, now.

4. Sud pralad (2004, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, THAILAND)

In terms of mere structure, this film is bonkers. Hardly ever has a film dropped as many jaws as Thai director Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s breakthrough feature Sud pralad (2004, Tropical Malady) during its initial festival release. At first glance, it might be tedious, it might be irritating, it might be, well, just too mysterious. It might feel too private. As one allows the images and the sounds to sink in, however, this masterful, dualistically structured film starts to make sense like Lynch’s Mulholland Drive (2001). Even more so than Lynch’s, I believe, Weerasethakul’s film is one of the best and most unique films ever made about love.

What begins as a love story between two men, a soldier and a country boy working at an ice factory, ending in an unexplained break-up, suddenly turns into a silent fable about a shape-shifting shaman and a soldier. The second part can be seen as an allegory for the first -- or vice versa. They comment on one another. They are co-dependent. They are lovers. There isn’t one without the other. What is more important than the logical connections between the two parts (one can either see them as flip sides of the same story or as a continuous story in the same fictive world) are their sensual and emotional resonances. Being a love story, the film’s English title (which is not a direct translation, one might add) already suggests a peculiar vision of love: not as a cure or as a utopia but as a malady, a sickness, something that consumes one’s body and soul. As the two men separate, they first devour each other. There is a sense of mystery in the air. What happened? Exactly. Who knows. Who’s to say?

Since their feelings -- both in initial infatuation and in the out-of-the-blue separation -- cannot be explained in words, they are articulated by the fable. The soldier is being consumed by the shaman, he is dying because of him, but he is also dependent on the shaman and must approach him. As the shaman shifts into a tiger, the aspect of consumption becomes poignantly discernible. Weerasethakul uses many lingering shots in the dark forest that suggest a fluctuation between the two characters. There is movement in the screen space, but is it the soldier or the tiger? They finally face each other in a bigger-than-life scene of intense stares that will haunt you for an eternity. The stare of the tiger occupies the screen space, dominating, hypnotizing the audience. There’s a strange sense of fear but also of lust; there’s an inexplicable desire to surrender as the malady takes over. Weerasethakul’s long take allows the tiger’s stare to sink in, to drill down to the spectator’s spine where its sensuous force begins to fester. The moment of devouring is at hand. This scene breaks hearts and sews them back together.

Weerasethakul’s inimitable cinematic discourse, which operates on the immediate level of senses and sensations, uncovers animals and other natural entities in their own right, as they appear, rather than as conventional metaphors for something else. They are embraced as the Other. Indeed: Sud pralad is a film about primordial otherness of everything else beyond oneself, a theme that Weerasethakul tackles by telling a love story. Because in love one experiences otherness most intimately but also most painfully. One might be very close to the other, but one also experiences the growing distance. One must confront the insurmountable challenge to understand the other. There is one’s own mind to keep one company, and then there is the rest of the world. There is the man devouring one’s hand and then going away for good. There are street lights in the night. There is music in the air. There is a sense of heartrending wonder. There is the intensely staring tiger ready to devour the one. And there is the one ready to take the plunge.

3. Distant Voices, Still Lives (1988, Terence Davies, UK)

By its enigmatic title alone, Terence Davies’ heavily autobiographical film Distant Voices, Still Lives (1988) invites expectations of originality, and those expectations are not disappointed to the slightest. The ambiguous title is rife with meaning, but at the most direct level it works as a structural point of reference since the film is distinctly divided into two separate parts. A story about a working-class family living in Liverpool, the film’s first part, “Distant Voices” focuses on the power the family’s father has on their co-existence in 1940′s, while the second part, “Still Lives” portrays the lives of the children in their early adulthood in the 1950′s -- away from the presence of the war but still far from the new youth culture that was about to emerge. Under the father’s abusive influence, they cried and sang in a bomb shelter; now, safe from heavy rain in a cinema, they cry as they watch Henry King’s Love Is a Many-Splendored Thing (1955). This is but one parallel in a film where things get entangled, where popular culture, communal singing, historical events, universal themes, and extremely personal memories fuse in an unprecedented network of cinematic thinking.

The peculiar two-part structure, made striking by the two-year gap in production and inevitable change in some of the crew, would be enough to mark the film as singular, but this narrative division is only one element in an idiosyncratic whole that constantly draws the spectator’s attention to the artificial nature of the cinematic representation in question. The film’s narration itself is self-aware to the extent that the spectator inevitably pays attention to it: the non-linear representation of past events in an order that seems associative at best is bound to make the spectator ponder representation. Davies thematizes representation or, more accurately put, memory, its mechanics, and the possibility of representing and remembering. On an immediately stylistic level, Davies employs heavy use of light coming from an off-screen source as well as over-exposed light in the screen space which, together with the pale and tainted colors that filter every image, give a peculiar, golden hue to the sepia-like, nostalgic mise-en-scène reminiscent of scuffed photographs. The cinematography, which varies between utter stillness and slow pans and dolly shots, often gives a strong impression of tableaux vivants from early cinema, which remind one of old family photographs. The same goes for the film’s strikingly exact and centralized compositions: never has a symmetrical two-shot felt this precise and powerful, static and dynamic at the same time -- artificial and proud of it.

On both levels of narration and style, Davies draws the spectator’s attention to the artificiality of everything: that all this has been “produced” -- structured and conditioned by a mind that is reminiscing something. That something belongs to a world that no longer is, and that never was just like this. It is an utterly unique world that is only here and now, in the moment one is watching this film and remembering it in their own mind. There is a sense of discipline and order which always leave something outside, making it absent, outside of memory’s reach, while encapsulating something, making it present, within memory’s constituted and conditioned sphere. On both levels, Davies’ film is strongly characterized by elements of distance and stillness as his filmic portrayal of family leaves his characters relatively distant, beyond our absolute reach, in picturesque mobile paintings that invite us to reflect what lies beyond their frames of stillness and distance, sight and sound.

2. Zerkalo (1975, Andrei Tarkovsky, USSR)

It’s nothing. Everything will be alright. Everything will be...

A monumental yet intimate masterpiece of memory, undoubtedly the best film on this list, if not simply the best film ever made, and one of the few films I have seen more than ten times, Andrei Tarkovsky’s most personal film Zerkalo (1975, Mirror) is beyond flawless. Like Bresson, Tarkovsky certainly has a very distinctive oeuvre that feels consistent in its stylistic unity, but there is something intensely singular about Zerkalo that elevates it above a body of six other masterpieces or fringe-masterpieces. Some directors have tried to follow Tarkovsky in creating their own mirrors, but none have achieved either the same level of quality or of uniqueness. The beautiful thing about the film is, and this is key to its uniqueness as well, that Tarkovsky manages to bring the private to the public (not only by juxtaposing his own experiences with Russian history but also by uncovering the universal structure in human experience) without ever coming close to sacrificing the innate privacy of some of his images at the altar of effortless intelligibility.

The first time viewer is bound to be confused by the enigma. In the course of repeated viewings, however, the fuzzy reflection begins to take shape. A dying poet recalls his life which unfolds in sequences that take place in three different time frames: his childhood in the early 30′s, his adolescence during WWII in the early 40′s, and his parenthood in the late 60′s. He ventures into the abyss of his suffering as well as that of his nation and humankind in general, but, in the midst of pain, a vague promise of peace is discovered. Mixing archival footage with traditional scenes of dialogue on different time frames, reciting poems and playing music, using oneiric images as well as concrete motifs of mirrors and fire, juxtaposing colors with sepia and black-and-white, Zerkalo coalesces the personal with the collective and the dreamlike with the material. It creates an unparalleled rhythm that has an eerie, otherworldly feel to it, which, nevertheless, feels so intimately tied to nature and sensation that one can almost touch it. But when you reach your hand toward the mirror, it once again reveals its elusive shape that escapes your grasp.

In its stream of impressions and ideas, the poetically flowing narrative of Zerkalo works as a lucid parable of the human mind. The mere viewing experience of the film works as a cheap form of psychoanalysis for some. Film scholar and programmer Antti Alanen calls it “a space odyssey into the interior of the psyche” [4]. The ambiguously focalized narration flows in ways which resemble free association. There is an event and there is another; there is an image, then a sound; there are pauses and gaps, inexplicable connections of heart and soul, lines drawn by a tormented mind trying to comprehend and grasp something that, as he himself puts it, cannot be expressed by words. From grand sights such as the collapse of the house and the flight of a bird through a window to tender details of a human hand before a flame, a redhead with a blistered lip in the snow, and a cut from one gaze to another, the film’s narrative flow follows a logic of its own, a logic on a higher level, a logic that feels consistent but cannot be laid out in non-cinematic terms. To some, there is spiritual force in this, the power of both the subconscious and the Hegelian Weltgeist traversing across the images.

Zerkalo tackles questions that are no less than the biggest but also the simplest in life: What is human life? What is its meaning? What is its meaning to us as individuals and as mankind? Why and how is it experienced as meaningful? There are no answers, there is no great revelation, and how could there be, but there are little junctures of awe, touches with the world, small manifestations of fire before us. The protagonist’s ex-wife wonders why something like the burning bush never appeared to her. We might wonder the same. In Tarkovsky’s mind, it seems to me, this is due to the loss of connection to something transcendent to us and our petty affairs -- not necessarily to god but perhaps to nature, to values as such, to what really matter, to our primordial origin. Or, perhaps, more modestly, there is a loss of connection to the mirrors around us, manifesting as the inability to accept bewilderment and live in lack of comprehension. The film is full of moments of such transcendence: the bird landing on the boy’s head in a strikingly beautiful composition of Brueghelian proportions, the massive gust of wind blowing over the departing man on the serene field after a chance encounter, the mysterious fall of an oil lamp from the table on the wooden floor, and the disappearance of a faint ring stain on a table as the lady vanishes. What are these magical moments, these manifestations of burning bushes, other than Ereignisse that ask us to accept irrationality, to look into the mirror and marvel? The great revelation to the big questions might never come, but the reflection on the mirror keeps getting clearer only to be beclouded again and vice versa.

1. Sans soleil (1983, Chris Marker, FRANCE)

Contrarily to what people say, the use of the first person in films tends to be a sign of humility: all I have to offer is myself. [5]

These are the words of Chris Marker. A private recluse, a documentarian, a poet and a reporter of the cinema, Marker escapes easy classification. The creator of the most unique short film La jétée (1962), Marker is also celebrated as the father of subjective documentary. After making what is most likely the best depiction of the political turmoil in the second half of the 20th century in Le fond de l’air est rouge (1977, A Grin without a Cat), Marker turned inward -- or did he? -- in the pioneer piece of whatever you want to call it, poetic essay film or subjective documentary, Sans soleil (1983, Sunless). “I could tell you that the film intended to be,” Marker affirms, “and is nothing more than a home movie. I really think that my main talent has been to find people to pay for my home movies.“ [6]

Anybody can make home movies, and everybody does in these pathetic days of YouTube vlogging, but only Marker can make home movies that are simultaneously ultimately his and ultimately ours. A home movie for the ages, Sans soleil tackles the perennial topic of French cinema (think of the whole oeuvre of Alain Resnais), the difficulty of memory, which has both individual and social implications for the representation of the past. In the beginning, there is an image of children in Iceland. Happiness signified. Is this a memory? Images signifying a happy childhood memory, any-memory-whatever. “How can you remember thirst,” asks the man behind the camera, whose letters the female voice-over, the alleged receiver of these letters with an alleged sender, another disembodied character like the man, reads out loud.

Marker’s Sans soleil does not develop ordinary motifs or conventional techniques in dealing with memory. No matter how innovative -- and groundbreaking -- Resnais’ methods are, they are no match for Marker’s meta-approach. Rather than thematizing memory with a device, Marker deals with the theme through itself, by trying to remember it, by trying to become conscious of itself. The man wonders how have people been able to remember anything without pictures. Pictures are the memory. Montage is the memory. Viewing the film is memory.

While timeless, Sans soleil is also absolutely a film of its time. It comes right out of the postmodern era when man’s relationship with history, time, memory, and space was challenged on all fronts of human thought and creativity. The history of the documentary film is filled with numerous travelogues -- from the ghost train films of early cinema to Flaherty’s Nanook of the North (1922) and Wright’s The Song of Ceylon (1934) -- but Marker’s Sans soleil challenges the whole possibility and meaningfulness of the travelogue. In his mind, in the mind of Sans soleil, time and space cannot be conveyed over individual, experienced knowledge. The poetic narration of Sans soleil constantly turns to itself and challenges its representation. The film consists of shots, which are more or less separate from one another, that are organized by the letters read by the woman, letters that she has received from a man, the man behind the camera. Thus there is a double focalization, the word and the image. When the levels of the image and the words of the letters occasionally coincide, the spectator is tempted to think of the images as shot by the man from his point of view, but Marker’s film seems to escape such an easy way out of the puzzle. Marker takes man’s relationship with history and the past by dealing with the relation between real and reconstructed memory. Is there a difference? Is there a difference between our collective history and our personal histories? Is there a difference between a home movie and a movie? Is knowledge of the world possible?

We know little of Marker’s private life. His most private and personal film, Sans soleil, perhaps paradoxically, adds nothing to this lack of knowledge. In a strange way, it achieves an extremely intimate level by creating a peculiar distance. It hides behind images and words. We never see the central characters. We see reconstruction. We see implications. We see conclusions without premises. We see the end of the road but not the road.

There are no clichés in Sans soleil because it is beyond the definition of cliché and convention. The man behind the camera has seen so much that at the moment only banality interests him, as he states in a letter. The unique and the original have become dull. The banal is the new unique. He preys banality like a bounty hunter. In this quest, banality turns into something else -- or does it? In a synthesis of banal moments, the montage of images becomes its own living thing.

A filmic version of stream of consciousness, the only structure of Sans soleil is its lack of structure. There is fragmentation on both the level of the whole and the level of the part. The words stop and random notes put a pause on a flow that, for a moment, seemed to have a clear structure. “By the way, did I tell you that there are emus in the Île de France?” The images freeze, the words stop, the images continue, the images give rise to a continuation into an unprecedented series of separate images. Yet, despite all of this, the film has a rhythm like no other, and it never feels scattered. It is cohesive on another level. It follows the unknown logic of its private internal auteur. Sans soleil is not remembered for its words nor for its images, but for the synthesis of it all -- and, most importantly, the impressions and feelings that arise from this synthesis. We do not remember individual shots, individual sentences, or at least we do not think of them. We remember the film.

I remember the cut from the Japanese dancing to an emu. I remember the abrupt cuts from the serene desert to the chaotic Hong Kong. I remember the cats in the temple. I remember. I remember the electronic sounds accompanying swans in a lake. I remember the counterpoint. I remember the tension, the voltage, the trance of it all. I remember the lack and the absence. I remember the presence and the richness. I remember the unique, the one and only, Sans soleil, the distant voice that both fades and stays in memory.

Some runner-uppers, or the mandatory honorable mentions: Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut (1999) and 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), Woody Allen’s Zelig (1983), Jean Vigo’s L’Atalante (1934), Dziga Vertov’s Chelovek s kino apparatom (1929), Souleymane Cissé’s Yeelen (1987), Leos Carax’s Mauvais sang (1986), Luis Buñuel’s L’Age d’Or (1930), Atom Egoyan’s Exotica (1994), David Lynch’s Dune (1984), Frank Perry’s The Swimmer (1968), Edward Dmytryk’s The Sniper (1952). Charles Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter (1955).

Notes:

[1] Truffaut, François. 1984. Hitchcock. Revised Edition. New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, p. 239-243.

[2] Bordwell, David. 2018. Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling. Chicago: Chicago University Press, p. 220.

[3] Bagh, Peter von. 1989. Elämää suuremmat elokuvat [Films Bigger Than Life]. Otava, p. 405. My own translation.

[4] https://www.bfi.org.uk/films-tv-people/sightandsoundpoll2012/voter/785.

[5] https://chrismarker.org/chris-marker/notes-to-theresa-on-sans-soleil-by-chris-marker/.

[6] Ibid.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Always read the fine print

The latest AOPA Air Safety Institute in-person seminar, “Peaks-to-Pavement… Applying Lessons from the Backcountry,” was a big hit. The crux of the seminar was emphasizing that if certain tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) kept you safe while operating in challenging backcountry conditions, then they’d probably also serve you well in more benign frontcountry flying.

I’d like to share some of my observations; a sort of PIREP summary of what I encountered during my presentations in six states/13 cities. Some caveats: This was not a Bush Pilot 101 course. We made it clear that this wasn’t a comprehensive how-to on backcountry flying, and stressed that pilots should seek qualified instruction before flying in the backcountry.

We also pointed out that the concept of “backcountry” has more to do with the condition of an airstrip, than its actual geographic location. They don’t have to be isolated, one-way in/out, dirt strips, at 9,000 ft MSL in the Rocky Mountains. You can have an airstrip that exhibits a lot of backcountry traits (short/soft/rough, sloped, obstructed takeoff and departure paths, no weather info or services available, etc.), located within earshot of the drive-thru window at your local, sea-level, Burger King.

I always enjoy poking, good-naturedly, at pilots who own their airplanes. It’s my contention that pilots ought to know their planes intimately, and not just from a seat-of-the-pants, stick-and-rudder proficiency standpoint. They should know everything about their plane that is, in fact, critical to their safe, proper, and efficient operation. The most important information is readily available; it’s right there in the Pilot Operating Handbook, or Owner’s/Aircraft Flight Manual.

Read the POH – all of it.

It was pretty obvious that some folks hadn’t cracked open their respective book(s) in a long time. Those who had studied their documents, tended to be familiar with the BIG PRINT stuff, like their Normal Procedures sections and Emergency checklists, but were not so well-versed when it came to the various Notes, Warnings, and Cautions found throughout. There’s a lot of free, but hard-earned, wisdom in that fine print, all intended to protect life and limb.

When it came to aircraft performance-related issues, lots of folks either never, or at least rarely, applied the adjustments/corrections, as directed by the manufacturer.

It was also clear some pilots had been operating (successfully, since they’re still alive and kicking), mostly by using various combinations of ROTs (Rules of Thumb), WOM (Word of Mouth), TLAR (That Looks About Right), etc., and in some cases, the good ol’ WAG (Wild A** Guess)! Since that stuff worked for them so far, and nothing bad had happened yet, they saw no reason to change their behavior.

One of the key areas we focused on was short and/or soft field operations, and all the associated factors that can ambush you. I’d start this discussion with a trick question: “What’s the FAA definition of a short field?”

The answer, of course, is there isn’t one; the pilot decides what is short, and therefore it’s subjective. What may be short for someone flying an ancient Stinson 108 at max gross weight, may not be short for a guy in a featherweight Carbon Cub. Equally as important, what is short for you today, may not be short for you tomorrow (OK, maybe next week), based on your proficiency in short field ops.

Deciding what constitutes a soft field was a bit easier; we generally agreed that anything not paved was soft, although there are certainly some very hard, but unpaved, surfaces.

My next question: “What’s the effect of grass on takeoff and landing distances?”

Most would answer correctly that grass increases takeoff distances, including both ground run and distance to clear the proverbial 50 ft. obstacle. But, by how much made them pause: “It depends; is the grass tall or short, wet or dry?” was a typical, but correct, response.

The answer may, or may not, be found in the performance chart “Notes” section in your plane’s POH. Some aircraft manufacturers direct you to make very specific adjustments to the info you derive from their charts or tables. Others, not so much.

Cessna’s guidance varies from “…on a dry, grass runway, increase takeoff distances [both “ground run” and “total to clear 50 ft. obstacle”] by 7% of the ‘total to clear 50 ft. obstacle’ figure” (1973 Cessna 150 Owner’s Manual) to “…on a dry, grass runway, increase distances by 15% of the ‘ground roll’ figure“ (1976 Cessna Skyhawk Model 172M Pilot’s Operating Handbook.)

Having different correction factors for different airplanes makes sense, because they are different. The danger comes when you arbitrarily apply an adjustment from a previously-owned plane to the one you’re flying right now… and it doesn’t end well.

Beechcraft must not trust pilots to do math; they publish separate charts just for grass surfaces: e.g., “Normal Takeoff Distance-Grass Surface.” However, the really fine print in their Notes section says, “For each 100 pounds below 2750 lbs., reduce tabulated distance by 7% and takeoff speed by 1 mph” (Beechcraft Sierra 200 B24R Pilot’s Operating Handbook). Now that’s some precision flight planning guidance!

Grass can definitely reduce runway performance – but by how much?

By comparison, the Piper Cherokee 140B Owner’s Handbook only provides a vanilla “Take-off Distance vs. Density Altitude” chart, with no guidance on adjustments.

At the extreme end of the manufacturer’s takeoff guidance spectrum, the one POH for all Piper Super Cubs simply states, “Don’t worry about it.” (I’m kidding.)

When it came to landing, a fair number of pilots were adamant that grass decreases landing distances.

No, it doesn’t. At least according to the manufacturers. I got into several heated discussions with folks who swore (while demonstrating it with their hands) that they could drop it in, over a 50 ft. obstacle, plant it firmly, dump the flaps, slam on the brakes, and stop less than 100 feet past the threshold.

I’d like to think I could too, but, for example, the Notes section on the “Short Field Landing Distance at 2550 Pounds” chart for a 180 hp Cessna 172S unequivocally states: “For operation on dry grass, INCREASE distances by 45% of the ‘ground roll’ figure.”

When landing our Cessna 150, the POH guidance is: “For operation on a dry, grass runway, INCREASE distances (both ‘ground roll’ and ‘total to clear 50 ft. obstacle’) by 20% of the ‘total to clear 50 ft. obstacle’ figure.”

Piper doesn’t even address landing on anything other than a “Paved Level Dry Runway, No Wind, Maximum Braking, Short Field Effort,” with power “Off” and 40 degrees of flaps, so it’s up to you to figure out your own correction calculus for any other combination.

Other aircraft’s POHs direct different adjustments; but in all cases, if they address grass landings, they’ll tell you to increase the distances – regardless of your technique.

Of course, the manufacturer is taking into account all the science behind the landing kinetics; boring stuff like mass, inertia, friction coefficients, braking effectiveness on different surfaces, etc. We all believe that with our finely-honed pilot skills, we can do way better than what their data says. But when it comes down to Art vs. Science, the latter usually wins.

My next question: “What are the effects of slope on takeoff and landing distances?” Now, it got really interesting!

Since not all manufacturers address the impact of slope on their specific airplanes, you really must contemplate the guidance that is out there and evaluate the TTPs you’re comfortable with.

Some commonly accepted, generic ROTs for the effects of slope, include the following relationships: a 1% upslope will increase effective takeoff distance by 5%; a 5% upslope will increase effective takeoff distance by 25%. (Note: Don’t ask me to quote a single source; there’s lots of reputable ones out there, including Wolfgang Langewiesche.)

If you further adjust/pad these numbers, or interpolate for a slope somewhere between 1% and 5 %, or greater (yikes!), the math overwhelmingly supports the commonly accepted notion that you “always” takeoff downhill and “always” land uphill.

But “always” isn’t the same as “always, always, always…” because there are times when it may be prudent to do the opposite: takeoff uphill and land downhill. Two of the key variables being wind direction and velocity.

Always land uphill… right?

Understanding the impact wind has on takeoff and landing distances was another area folks seemed content to guess at, instead of applying specific POH guidance.

The Cessna 172S “Short Field Takeoff Distance at 2550 Pounds” chart Notes state: “Decrease distances 10% for each 9 knots headwind.” You could be confronted with a situation where the 5% increase in takeoff distance caused by a 1% upslope, is more than offset by the 10% decrease in distance afforded by a headwind.

Even more interesting, the Notes also add: “For operations with TAIL WINDS up to 10 knots, increase distances by 10% for each 2 knots.”

Although it is absolutely desirable that you always take off and land into the wind, you might not have that option. The manufacturer may provide the data you need to make a pragmatic decision regarding tailwind operations. The real question is: are you comfortable and competent enough to do it? Or the more appropriate question: should you? The best answer might be, “Wait for conditions to improve.”

All these discussions led nicely into the next topic that people tended to guess about, possibly at their peril: can I clear that obstacle off the end of the runway?

Obstacles aren’t always the natural kind (high terrain, tall trees, Bigfoot, etc.); some of the most dangerous ones are man-made (powerlines, towers, bridges, buildings, wind turbines) because we’ve gotten so used to seeing them, they’ve become innocuous. For our discussion, “Spiraling up over the airfield” wasn’t an option; we’ll talk about the impact of density altitude on aircraft performance in another segment.

The concept of flying an Obstacle Departure Procedure (ODP) doesn’t just apply to IFR operations.

The challenge is that ODPs require understanding climb gradient requirements versus rate of climb requirements, and how the two are related. The idea of flying a self-engineered ODP, if required, to escape from an obstructed environment, shouldn’t intimidate anyone – if they know how to do the math.

There are two key ingredients needed to design your own ODP. First, you must calculate your ground speed. Second, you must know how tall and how far away the obstacle is, so you can calculate the climb gradient required; i.e., how many feet per mile you’ve got to climb to clear it.

Since we don’t have climb gradient “Feet per Mile” gauges in our planes, we’ve got to come up with a performance metric we can use: our rate of climb in Feet per Minute.

You don’t need a formal departure procedure to do some basic climb math.

The math is simple: multiply your groundspeed (we’ll use 70 mph), by the climb gradient required (e.g., a mountain ridge, 800 ft. above field elevation, 2 miles away = 400 ft. per mile): 70 X 400 =28,000.

Take the “28,000” number, divide it by 60, and you’ve just come up with 467 feet per minute – the rate of climb required to clear the ridge. Having a vertical speed indicator is a bonus, but if you’re familiar enough with your plane’s performance, you shouldn’t need one.

The bottom line: don’t tempt fate. If you determine that you’ll need to generate a 467 foot-per-minute rate of climb, and on your best day, at sea level, your 65 hp Champ can barely wheeze at 200 feet per minute… don’t even bother starting the engine.

Note: if you want to err on the conservative/safe side, overestimate your groundspeed – that means you’ll be closing on the obstacle quicker and will require a higher rate of climb.

Of course, you can also just cheat and carry the descent/climb tables from a government approach plate book. They’ve done the math for you.

At the End of the Day