#there was a truck stuck in the middle of all lanes creating a traffic jam but at least my bus was finally able to get past

Text

so let's play a game called "is the dude who only talks to me when he's drunk at parties etc gonna talk to me in class today"

#my bet is on no 🥰#i don't care either way#im just cringing bc when he talked to me last friday i was giggling and being annoying..... bc drunk me likes attention </3 ew#anyways let's see if i even make it to class the weather is awful bc of snowstorm 🥴#there was a truck stuck in the middle of all lanes creating a traffic jam but at least my bus was finally able to get past#maybe I'll just be late. and probably won't be the only one.....#my posts

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

wielding fire

This is a windmill fan blade. It measures 37.5 meters long. How do I know?

It was the summer of 2009. I was 19, having just finished my freshman year in college, visiting my aunt and uncle in Beijing for the summer. My uncle took me and my cousin on a day trip to Datong China to visit the Yungang Grottoes. As usual with any long car ride, I was in my default mode: sitting shotgun next to my uncle driving the car, headphones in, listening to my iPod, taking in the sights passing by.

I always enjoyed long car rides that way, letting my thoughts come and go just as the world passed me by, from local roads to the long highway.

Then we get stuck in traffic. It was the weekend, but somehow cars started jamming up anyway. All the while, I just sat there, listening to Japanese rock and Jason Harwell. Moments later we see this giant windmill blade on a truck, practically teetering out of the truck’s back like a dinosaur tail.

My uncle decides to shift a lane to the truck’s right side. And soon enough, as we moved slowly through the traffic jam, we stopped right next to the truck drivers. My uncle unrolled his car window and shouted, “Hey, where are you guys going? How long is that thing?”

I forget where they were going, but the drivers replied 37.5 meters. With that, my uncle turned to look at me, his eyes piercing into my psyche. By then, one of my earbuds was off, and I just nodded. I turned off my iPod and took my headphones off the rest of the car ride. No words were said, but I understood what my uncle meant with his stare.

Earlier that summer, my uncle taught me a Confucius proverb: 三人行必有我师. It literally translates to “Three people walking past me, one of them must be my teacher.” Essentially, it means that you can learn a thing or two from anyone you meet. Now, in a traffic jam next to a windmill truck, my uncle had plainly demonstrated that to me.

But the reasons why my uncle taught me that proverb in the first place spanned beyond the the simple act of asking people questions. By the time of this day trip, I was probably two months in my three month summer vacation in China. A lot had taken place before that, a cumulation of moments and discussions that built up to that moment in the trip, in a traffic jam next to a windmill blade, when my approach to life started to turn.

At the end of the trip, sitting on an airport tram for the flight return home, I knew that I had changed. It’s been almost six years since that trip and I think I’m finally starting to understand and articulate how I felt and viewed my life from that point on.

While I had spent a few summers with my aunt and uncle in Beijing before, my 2009 visit was the first time they would see me as a young adult. The first time I really got to know them was when I was eight years old, when I traveled to Beijing alone. It was a bit scary being away from my parents for a summer, but my aunt and uncle made it fun, with visits to the beach, the zoo. Kids stuff.

My aunt is best described as a cross between Katherine Hepburn and Olenna Tyrell, strong willed and sharp minded. My mother fondly remembers one day in high school when my aunt ran up to her eagerly asking “Hey sis! What do people think of me? Do people find me fierce? Do they? Do they?!” In dinner conversations with her friends, my aunt spoke with quick wit and conviction, usually making an astute observation. When she enters the room to join her friends at a restaurant, sometimes someone would declare “The teacher has arrived.”

My uncle is best described as a cross between Vito Corleone and Winston Churchill, a straight up boss. The fact that he smoked cigarettes only further strengthened the illusion that his spoken words carried gravity. After a puff of smoke, he would speak in a deep raspy voice, his index and middle finger pointing authoritatively with a cigarette in between them.

My aunt and uncle both studied economics and law, which they claimed to be a source of their success as stock brokers. “We know the rules of the game,” they declare, every time the subject comes up.

So one year into college, I visited them again, excited for a summer vacation in China, cheery with naive optimism, looking forward to a time to sit back and relax. Little did I know, I was walking into a lion’s den, inhabited by two people hardened in demeanor and fiery in spirit.

Back in high school, my ideal vacation consisted of drinking iced ginger ale or lime tea while reading books, playing Counterstrike, and watching anime and movies. Academically, I worked hard enough to get straight A’s, but I was not a person who took initiative beyond what was asked. I was acting in response to external goals: get good grades, get into college, make sure my parents don’t yell at me. One year into college, and my attitudes were pretty much the same, just blindly following a formula that had been ingrained from going to a relatively good public school. Once I settled into my aunt and uncle’s apartment, I spent the days surfing the web on my laptop, watch HBO and CNN (the only two English language TV channels they had), or read a book.

Despite having this general restful mode, I did have one pre-determined goal for this trip. During my freshman year, I took an introductory class on Chinese history. After taking the class, I asked the professor what I should ask my aunt and uncle, on their views of Chinese history, particularly the modern half. Looking back, I realize I was incredibly unaware of the seriousness that that discussion would entail. I was casually curious and wanted to ask them questions because I felt like I knew something and wanted a higher level discussion.

So the day came, when, as I finished my dinner, I asked my aunt and uncle a few questions about modern Chinese history. I can’t remember what I asked that day because my memory is completely overwhelmed by the near-shouting level of their voices as they responded. They were immediately outraged at how unaware I was about what I was asking. All I remember was that they started talking about geography, how the availability of resources largely governed the development of China’s long history and large civilization. My intention was to get a grasp of modern China’s history, but they went back to square one, considering me too unfamiliar with basic concepts to deserve that high level of a discussion.

I was a bit disappointed. Dinner conversations from then on basically became lectures of sorts, where my aunt and uncle would express their views on the world and what I should do to become successful. It was in those conversations that they also laid out how naive I was in my behavior and how lax I was in this trip. I was sometimes dismissive of the seriousness of these conversations. This was supposed to be a vacation. Why the hell are they always rambling on and on about how I should be conscious of my abilities and career? Overall, the conversations turned out to go in a very different direction from where I wanted.

Of course I was struck by how judgmental they were being. The fact that I studied engineering only made things worse. “Listen here you uncultured philistine,” they’d remark, ���Given our liberal arts backgrounds, we’ll be sure to ingrain in you some cultural understanding by the time you leave!”

Over time, I began to understand their perspective. It became apparent that a majority of my “understanding” of the world seemed to stem from watching TV and movies. “Sometimes, you have to get to the source,” my aunt advised, “A lot of things are interpretations of interpretations of interpretations.”

Moreover, here I was, in a foreign country, and I rarely asked questions about what I was seeing on a daily basis. This led to the conversation where my uncle taught me the Confucian proverb.

All of these conversations were a steady build up to the day trip to Yungang Grottoes, the day my uncle rolled up next to a truck in a traffic jam and asked the driver about the windmill blade’s length.

When we arrived at Yungang Grottoes , we were immediately in awe of the incredible sights.

We paid for a tour guide. I tried my best to understand her speaking Mandarin. We both marveled at the enormity of sculptures before us. “Imagine, all of this was once painted and layered with gold leaf. Just imagine!” my uncle would proclaim, pointing with his two fingers, this time without a cigarette. I tried to come up with a question or two, but really couldn’t come up with anything, too overwhelmed with the task of taking it all in.

A tourist group shuffles past us, almost photos. Then, after a few short minutes, they leave, except for a boy and his father. “Hey, stand there a sec,” the father directed his son to stand in front of the statue. One second later, the father takes a photo, and then the next second they scurry off to catch up with the rest of the group.

It appeared as the perfect antithesis to what my uncle did at the traffic jam next to the windmill blade truck. Traveling affords a great deal of opportunities, only if you are cognizant of those opportunities and carefully take the time to follow your curiosities and listen to what people have to say. It becomes very meaningless if you frantically snap photos from one stop to the next.

After I came back from the trip, I realized the broader implications about what they were telling me. Life is filled with possibilities: ideas to explore, places to experience, potentials to realize. I had been a bit too passive up until then. As Theodore Roosevelt would say, “Get action. Do things; be sane; don’t fritter away your time; create, act, take a place wherever you are and be somebody; get action.”

This was something my parents had been trying to impress on me for my whole life. But it wasn’t until my aunt and uncle expressed the same sentiments in their conversations and actions that I finally started to do something about it.

By the time I was in college, a bunch of firewood had already accumulated inside my head: a habit of watching TEDTalks and reading stuff on Google Reader, a dormant interest in writing, and bunch of “Hey, wouldn’t it be cool if...” ideas scattered like wood chips and torn up newspapers in a dusty fireplace.

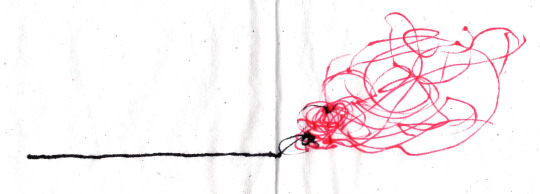

And with their conversations, my aunt and uncle lit up a tiny spark inside that fireplace.

A flame quickly caught on. Almost immediately, I felt driven to do things with some sense of purpose. It was about doing what I thought would be a good idea, not just talking about it. It was about following through. It was about recognizing what opportunities were in front of me and taking them.

Around this time, I was an intern at an architectural design office. I was unpaid and hardly could do anything, not understanding a lot of Chinese, and not able to even use drafting software like Sketchup and AutoCAD. I had gotten the position simply through family connections. And so, for the first few days, I sat and did absolutely nothing. I browsed the web and read online newspapers.

After the day trip, I started looking around the office and noticed a good number of architecture books written in English. Some of them also had Chinese and English written side by side. That weekend, I went to a bookstore and bought a Chinese English dictionary. The next few days, to the office’s amusement, I sat down at my desk, with the dictionary, reading DETAIL magazine articles written in the two languages, and jotting down words I didn’t recognize in Chinese. The English translation on the opposite side helped clarify any ambiguous definitions I found.

Back at my aunt and uncles, our conversations continued. I started to enjoy listening to them. I can still picture those moments in my mind’s eye. My uncle is smoking, the fumes hovering over the warm glow of an antiquated looking shaded lamp by his side. My aunt sits in a grand arm chair discussing her days working in a bank, earning her first paycheck and bonus.

When I got back to campus after that summer, I could hear my uncle’s voice as if he were with me, commenting on whatever was fascinating: a building on campus, the surrounding natural scenery, or some point made in talk or lecture. Within the first few days of arriving on campus, before the academic year even began, I went to the library to check out books. I checked out a book my uncle recommended, A Short History of Nearly Everything, as well as a book about Tadao Ando, an architect I read about a few times in the architecture design office. Later on, I attended a guest lecture on mathematics and why golf balls had dimples. That winter break, I asked my dad to have a few books checked out from the local library before I got back.

From then on, I enjoyed reading a lot more than I used to. Reading a book, I realized, was just like sitting down with another aunt or uncle telling his or her stories.

I’ve sat with Uncle Malcolm, who talked about first impressions and how they can be deceiving, Uncle David on his time in Japanese hotels and smoking, Uncle Dick on physics, the nature of curiosity, and understanding the world, Uncle Tim on what it takes to be effective and in control of your life, Uncle Seth on why the world needs more purple cows and how dips in performance are critical moments, Uncle Ben and Aunt Rosamund on how to see possibilities in any scenario, Uncle Steve on the early days of computing and phone hacking, Aunt Cheryl on her hiking trip and the nature of death and loss.

Vacations, weekends, off time, now appeared to be opportunities to make something, pursue side projects. Reading about people like Austin Kleon and Ben Barry only further stoked the fire, as they served as examples of how to take initiative of things, however silly or irrelevant to one’s “career” they may appear.

My life since that trip has been a richer and more meaningful adventure. Who I am today can be significantly attributed to what my aunt and uncle impressed on me that summer, a driving fire.

I must admit, however, that that same fire has brought on some unexpected challenges. My mind is now flooded with ideas, more than I can possibly act on. And yet every idea I think of makes me feel obligated to follow through on it. It’s hard to say no and even harder when I feel like I am not living up to my full potential. When I’m with other people, sometimes the conversations feel so banal and absurd. I once felt so bored during a conversation about cute dogs, I thought, “Huh...so this is what a normal conversation feels like.”

My aunt and uncle did help stoke a fire inside me, but they left me to figure out how to wield it.

These days, I’m only beginning to balance my approaches to life, the passive and the active. It can be fun to make things and dive deep into ideas with friends. But small talk and “just being” have their benefits as well. I have to learn to recognize the flow of life’s pace, the moments when it stands still and the times it leaps and gallops into the unknown.

______

Recently, I competed in a wushu competition for the first time. Thanks to my laid back attitude in high school, the idea of competing never crossed my mind when I was a teenager. At the end of the competition, I felt content to be finally following through on something I loved doing. A few weeks ago, as I was writing this blog post, my mom told me my aunt and uncle were getting divorced. Initially I was shocked but not saddened by the news, because I didn’t think it was going affect me that much. Then a question came to mind. As my aunt is my mother’s sister, I knew that I would still call her “aunt” when I see her.

“But what do I call him now? Do I still call him “uncle” when I see him?”

My mom replied, “What makes you think you’ll ever see him again?”

My heart sank. She then explained that he had already moved on with his life and was already seeing someone else. There was now no reason for him to ever see me.

If I ever do see him again, I will still greet him first with “hello uncle”, not out of a naive ignorance of the divorce, but out of familiarity and gratitude. He was a mentor. He was family.

0 notes