#something about combining the artistic with the scientific and ending up with hawk

Text

At the phase of total normalcy about prewar childhood headcanons where I'm holding up pictures of early 1900s ballet dancers next to young pictures of Alan and making very thoughtful sounds, don't mind me

#something something i'm going to devise a headcanon about hawkeye's mother that is just so silly to everyone but me—#something about combining the artistic with the scientific and ending up with hawk#who operates in the area between the art and the science of medicine#appeals to me in a way that i cannot describe to you#i'm having a great time though these women are so strong-featured and stunning and i'm gay#my ramblings

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who Is The Most Intelligent Person To Ever Live?

So – who’s the smartest person to have ever lived? It’s likely that a handful of names just popped into your head. You’re on a science site, so it’s probable that Einstein cropped up, as well as Feynman, Hawking, Curie, and a few others. Some would vociferously argue for Tesla. Others would suggest Faraday or da Vinci.

Based on his body of work, it’s entirely unsurprising that “Einstein” is synonymous with “genius”, much in the way Newton was back in the day. Their incredible scientific and cultural legacies have led to both of them being described as some of the smartest people in history – but does such a phrase have any inherent meaning? Can anyone ever own that title without equivocation?

Human civilization has been around for many millennia; our species emerged from the tapestry of evolution way before then, perhaps around 350,000 years before the present day. Ever since it’s been a story told in countless chapters, each one often featuring an individual whose unique life opportunities, combined with their ingenuity, has changed everything.

Einstein wouldn’t have made his famous discoveries had it not been for the work of Aristotle and Copernicus, Galileo and the Herschels. Darwin wouldn’t have been prompted to advance his theories if it wasn’t for the work of Charles Lyell, a pioneering professor of geology.

Who’s to claim that Einstein is the smartest of them all when there are brilliant mathematicians like Srinivasa Ramanujan – whose contributions to the field are arguably comparable to that of Newton, the inventor of the game-changing calculus?

Today, these scientific discoveries come as part of a team, and it’s rare a single person has such heft in that way. As the world becomes more global, collaborations become wider and more international – and who are we to say is the smartest among them? As is often paraphrased, we all stand on the shoulders of giants, and it’s this stream of genius that drives progress.

Intelligence is also defined somewhat subjectively. Those history-makers were all science-themed examples, but what of the arts and humanities? What about the world of politics or economics? Although it’s perhaps easy to pick a scientist as the “smartest person ever”, you could surely argue that a military general, an artist, a novelist, or a musician could also take that spot.

Additionally, what an entrepreneur, say, considers to be intelligence may overlap a little with what a scientist suggests defines intelligence, but there are discrepancies. These discrepancies, valid or not, make deciding what constitutes intelligence a Sisyphean task.

This confusion is somewhat succinctly summarized by a 1971 paper, which described a “variety of problems arising out of current practices in the measurement of intelligence,” including, rather importantly, “the gross imprecision of definitions of intelligence.”

Saying that, if you really wanted to rank someone based on an objective measure of intelligence, you might be tempted to use IQ. As you’d expect, there’s a problem with that too, apart from the obvious fact that most of the candidates for the smartest people that have ever lived are now dead. Posthumous IQ tests aren’t exactly reliable, but that hasn’t stopped people from trying.

There are a wide range of IQ tests, the nuances of which we won’t get into here. Essentially, IQ tests measure the ability of someone to process both pre-existing information and brand-new data. W. Joel Schneider, a particularly eloquent American psychologist, explained back in 2014 that “good IQ tests should measure aspects of visual-spatial processing and auditory processing, as well as short-term memory, and processing speed.”

IQs are scored on a bell curve, so those at the far-left and far-right of the central distribution peak – where most of the population fall into – are exceptions.

A score of 100 is nominally the average, and, depending on the variety of the test you take, the maximum score can be around 161/162 on the text-heavy Cattell III B exam, or 183 on the diagrammatical Cattell Culture Fair III A exam. This doesn’t mean a higher IQ isn’t possible; upper limits are there because, toward the high end of the bell curve, the reliability of gauging IQ drops off.

Nevertheless, some rather unusual (and questionable) methods exist for estimating people’s IQ, including one in which the accomplishments of a person’s life are used to “calculate” a score. Suffice to say, it’s not a great method, but this type of estimation is generally why Shakespeare’s IQ is claimed to be around 210, Newton’s around 190-200, and Goethe – a German polymath – to be as high as 225.

As far as we can tell, America’s Marilyn vos Savant, who took an adult Stanford-Binet IQ test at age 10, has a Guinness World Records-verified IQ score of 228. This is considered to be the world’s highest recorded IQ.

Other living figures, including Hawking, may have IQs attached to their name, but they don’t necessarily know what they are. The theoretical physicist famously told a New York Times reporter in 2004 that he had “no idea” what his IQ was, adding: “People who boast about their IQ are losers.”

Schneider also points out that such values aren’t so valuable in isolation; their true value shines when you see what they often correlate with, such as creativity and general life success. IQ is a sort of gauge of current potential.

The most salient point here, though, is that it’s debatable as to what an IQ test actually measures and what it fails to measure. They’re generally seen as a good measure of reasoning and problem solving, but that’s not the whole story.

Some studies suggest that IQ bumps are linked to how motivated the person taking the test is; raw intelligence alone isn’t enough to guarantee greatness. Intelligence changes over time too, for a whole host of reasons – so IQ tests only measure a person’s cognitive abilities at that point in time.

These examinations also don’t measure the full spectrum of a person’s intelligence. Emotional intelligence, for example, isn’t quantifiable using IQ tests, and neither is your practical intelligence. IQ tests don’t measure curiosity, a key feature of what many refer to as “genius”.

Something else that must be emphasized is that such tests don’t take into account the fact that people’s life circumstances radically differ. Intelligence is less impactful if the means to translate that into discoveries and advancements isn’t around.

From financial restrictions to the coincidental geography and time of their birth, there are likely plenty of geniuses that have, and will, elude the pages of history through no fault of their own. Lest we forget that, with some historical examples, women have been – and still are – suppressed by systemic sexism, which has undoubtedly condemned many to a life lived in the shadows of men.

Don’t get us wrong: IQ tests are a useful measure, but they don’t have a monopoly on intelligence. They’re imperfect in many ways, and you certainly can’t use them as a quick way to rank a person’s smarts, living or dead.

Considering all the above, I’d strongly argue that you cannot say that any one individual person was the smartest person to ever have lived. It’s not just that the question is complex; it’s fairly meaningless. Instead, let’s make sure we do all we can to elevate the disadvantaged, and support each new intellect that arises – in whatever form that takes – so new geniuses don’t slip through the cracks.

Read more: http://www.iflscience.com/brain/who-is-the-most-intelligent-person-to-ever-live/

from Viral News HQ https://ift.tt/2v1ahEP

via Viral News HQ

0 notes

Text

Art in Context

I have just got back from a lecture tour from Adelaide to Sydney. After 21 talks in 24 days – not to mention 19 lunches and 16 dinners with members of the various committees - I was bound to have become a bit disoriented. But, perhaps, this feeling may have been exacerbated because the itinerary, which had been worked out with great skill by the Association of Design and Fine Arts Societies of Australia, had a habit of looping around and doubling-back on itself. Hence Adelaide, Melbourne and Sydney all seemed to appear and disappear with startling regularity. All perfectly logical, as it turned out, but it got me thinking about the links between the places that I was visiting and the talks that I was giving as well as about the idiosyncratic relationship that Australia seems to have with maps.

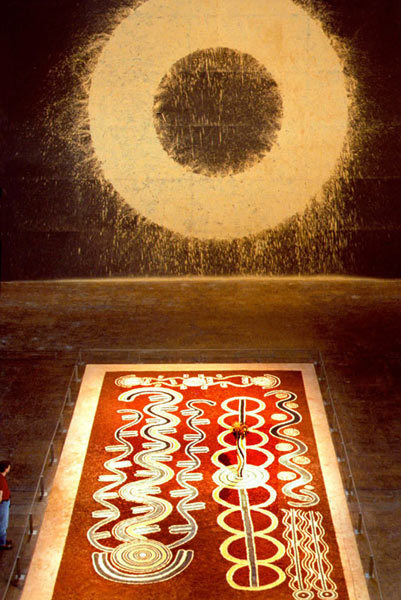

I first noticed this in Adelaide when I came across a chart that the anthropologist Norman Tindale had created, which disproved the notion of Australia as a continent that had been populated by nomadic people before the arrival of the Europeans. That afternoon I had been talking about Jacquetta Hawkes’ use of Henry Moore’s drawings of quasi-archaeological figures in her book Back to a Land to illustrate the way in which ancient sites help to shape our perceptions of a landscape. What I found particularly interesting, however, was that Tindale had used language variations to map the locations of different indigenous groups. I was reminded of this a few days later when comparing Richard Long’s circular wall-piece at the 1988 exhibition, Magiciens de la terre, to a piece by an indigenous Australian artist on the floor next to it. I had just been explaining how Long recorded his subjective impressions – including the snatches of pop songs that came into his head – and juxtaposed them with the place names on hi walks. I then remembered how one of the audience had told me that indigenous people had chosen the place names in the area because they imitated the sounds made by frogs in specific locations. They were thus useful in helping them to find their way across an otherwise undifferentiated landscape.

The preconceived way in which Long imposes lines and circles on a landscape evokes a wonderful description in Voss, Patrick White’s great novel of Australian exploration. In it the eponymous hero, who is trying to find his way across the continent, sends back his indigenous guide for help but the latter gives up since he becomes distracted by his habit of living in the moment around him. I was reminded of Voss’s hubris once again when someone told me that when gold was discovered near Melbourne the locals drew a misleading map, which indicated that their town was much closer to it than Geelong, thus ensuring the city’s future development as the state capital. Similarly, towards the end of my trip another of my hosts told me that the famous trio of explorers who discovered a trail over the Blue Mountains may have been accompanied by an indigenous guide or at the very least have followed paths that had been known to local people.

The relationship of landscape to national identity reappeared in a lecture about Munch in the form of a comparison of the romantic landscapes of the Norwegian artist, Johann Christian Dahl, to the work of the Australian painter Eugene von Guerard. Most of my lectures, however, seemed to focus on the way in which artists used the language of history painting to create statements about contemporary life. This was true of a talk about the links between Rembrandt’s Night Watch and the role of the militia at the start of the Dutch revolt and of another about Joseph Wright of Derby’s allegories of the philosophical and scientific ideas of 18th century Britain. Since several of my talks were about the European Enlightenment, I was also intrigued to discover how the artists who accompanied Baudin, the French explorer who came across Flinders in Encounter Bay, portrayed indigenous people in sympathetic poses in accordance with preconceived ideas of the ‘noble savage’ that they had derived from Lahontan and Robinson Crusoe

.

The most iconic of Australian heroes is, of course, Ned Kelly and I was fascinated to find how much Sidney Nolan’s great series about the outlaw resonated more strongly in Australia than when I had first seen it in England. The same was true of Jackson Pollock’s Blue Poles whose purchase by the National Gallery of Australia for AS$1.3m in 1973 created a political scandal for Gough Whitlam’s government. Watching Australians queue up to take their selfies with the painting – now estimated to be worth about $300 million - it seemed far more significant than it had at its recent showing at the Royal Academy or when it left the artist’s studio. Nolan explained his curious decision to to adopt a comic opera idiom for the series because he felt that the policemen who were pursuing Ned had been naïve to sleep in hammocks in the wilderness and to burn trees for warmth, which gave away their position. Indeed, there is something of the Pirates of Penzance about his portrayal of one of the members of the posse when he unwisely decides to take Ned Kelly’s wife upon his knee.

Equally hagiographic but in a very different way were the works of Rodel Tapaya, an artist from the Philippines, whose paintings were being exhibited in the gallery adjacent to the series in Canberra. His combination of south Asian animist beliefs with post-modernist extravagance and sci-fi dystopia provided an interesting contrast to the work of several indigenous Australian artists on show.

Among them were the late Rover Thomas whose laconic paintings read both as depictions of the outback and as modernist abstractions. Only when one reads the labels does one find that their titles refer to actual events in the recent history of indigenous people from the devastation of Cyclone Tracy to the shooting of a cattle rustler. Like his fellow artist from the Kimberley, Queenie McKenzie, Thomas has become an important figure in the reinterpretation of Australian history by indigenous people. One of the most recent expressions of this is the decision by the current director of the war memorial in Canberra to show paintings of the conflicts that they waged against the settlers. The huge number of young people that Australia lost in two world wars made this a controversial decision. Although comparable to the Imperial War Museum North’s display of a police shields from the miners’ strike or memorabilia from Greenham Common, its real significance can only be appreciated on the spot.

The week before I left for Australia I happened to visit Highgate Cemetery where Sidney Nolan is buried a stone’s throw from Karl Marx. Despite my best efforts, I was unable to find his grave, which is located next to a narrow path among a group of other émigrés. In retrospect, it seems a fitting metaphor for how far my journey would lead me off the map.

0 notes