#so meanwhile the right have all their votes concentrated on mostly two parties

Text

the spanish left when the far right has a rise in popularity after they've spent the last few years playing stupid identity politics games, sucking up to the us, embarrassing themselves in international relationships, passing badly redacted and shitty laws in the name of feminism that only ended up screwing up women and victims of sexual assault, while doing absolutely nothing to stop the rise of costs of living and help working class people and families

#oh my god who could've predicted this!#right wing parties are all united meanwhile the ''''left'''' do nothing but infight and start a billion different political parties#so meanwhile the right have all their votes concentrated on mostly two parties#the left has it all dispersed in a dozen parties#working class: help im drowning in debt i can't afford to pay rent my kids are starving im about to get kicked out of my house#la gilipollas de irene montero: vote for my buddy!!!!! bc shes a deaf lesbian 🤪#the general elections are gonna be funnnnn#I thought vox was gonna have waaay more votes tbh considering the political climate#forgot conservatives usually play it safe and mostly just vote pp#i was kinda expecting them to pull a 2016 podemos but usually the left is way more risky with the way they vote#talking about podemos....... lmfao#they're in the absolute mud#con las leys de mierda que pasaron los dos últimos años y la campaña con los eventos drag que hicieron es lo que se merecen la verdad#no puedes ir con esa mierda de discurso viendo tal y como están las cosas en españa y esperar no llevarte la hostia descomunal#tienes a medio país en la ruina viviendo en zulos y con los precios de todo por las nubes#cagon dios aprovecha y haz campaña en torno a eso y déjate de las gilipolleces de los guiris#qué cojones le importa al votante medio las políticas de identidades si lo que les preocupa es que no llegan a fin de mes#es que uf#luego a llorar porque los imbéciles de vox se llevan todos los votos de las zonas rurales y la clase obrera#que a ellos les importa 2 cojones los trabajadores y las familias obreras pero al menos saben qué hacer para ganarse el voto

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

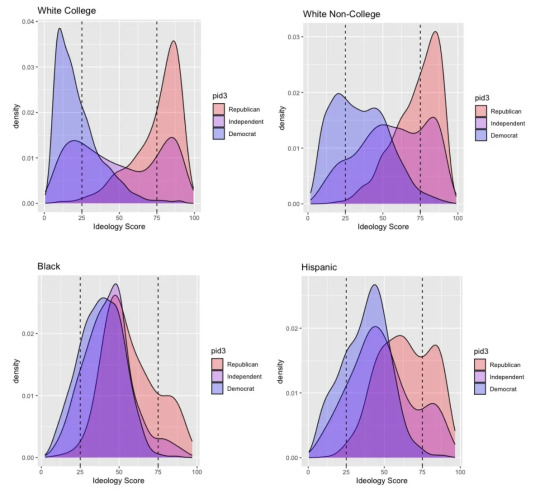

The polarized partisan hellscape of today is mostly a white (college) thing.

If everything seems polarized these days, it’s probably because of the circles you run in. Not everyone is like this. And the people that aren’t—the multiracial working class—are wildly underrepresented in political media.

The Shape of Polarization in America, Patrick Ruffini

Different groups are polarized in different ways, and by this I mean that while white college graduates are extremely polarized in their views, Black and Hispanic voters are hardly polarized at all, holding largely moderate positions on policy that don’t shift dramatically as a result of their partisanship. Whites with college degrees are outliers in the levels of polarization, with partisans in this group tending to cluster at polarized extremes on policy.

Another way to boil this down is to bucket people into different ideological camps based on a 75-percent cutoff for ideological consistency. So, giving the conservative or liberal answer more than 75 percent of the time places you in each of those camps. Otherwise, you’re in a non-ideological middle ground. The 75 percent cutoff is an important one. Above we find Assad-like margins for Donald Trump or Joe Biden in 2020 of more than 98 percent. If you’re above this threshold, you’re not persuadable in the slightest. In the middle, your vote is basically up-for-grabs, progressing from one candidate to other in sliding scale fashion according to your policy views.

In each group but for one, solid majorities are in the non-ideological middle: 83 percent of Black voters, 77 percent of Hispanic voters, 69 percent of Asian-American voters, 58 percent of white non-college voters, and 56 percent of Native and other voters. And here again, one of these groups is not like the other: just 38 percent of white college graduates are in the middle, with large groups of extremely polarized liberals and conservatives. White college graduates also stand out in their representation of polarized liberals, with a concentration of them that’s nearly double that of any other group. And in the ranks of polarized liberals, there’s a notable absence of voters of color. Within a group of voters who agree with liberal positions more than 90 percent of the time, white voters with college degrees outnumber Black voters by 20-to-1, 60 to 3 percent.

[...]

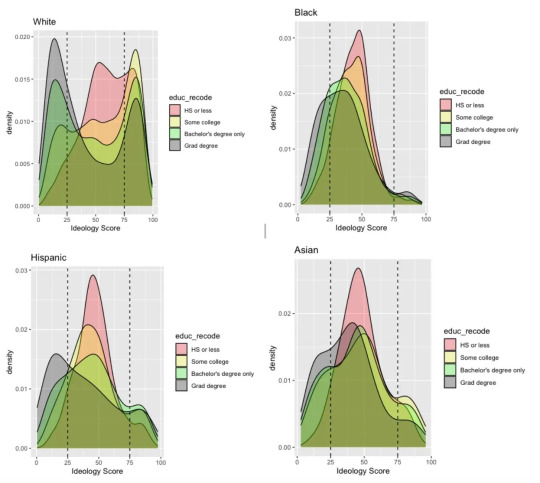

It turns out there’s good reason to single out white college graduates. Nonwhites are mostly similar in their views across education levels, with only a slightly more liberal peak among those with graduate degrees compared with those who only graduated high school. For whites, it’s a different story. These two groups are on different planets ideologically. The more highly educated a white person is, the more consistent and extreme their policy positions. Meanwhile, nonwhite voters at all education levels tend to cluster more in the middle.

It’s not that whites with college degrees are the only group that’s polarized. White Republicans without college degrees are highly polarized on the right. White Democrats without degrees are pulled a bit rightward based on the group norm, so they appear as a relatively moderate group. Hispanic Republicans are showing signs of becoming more ideologically polarized.

But the situation for whites with college degrees is unique, with twin ideological peaks on the left and the right. Citing the work of the Hidden Tribes project, David Brooks has called this the “Rich White Civil War.” The CES data bears this out: ideological polarization is mostly a function of being white and having set foot on a college campus. Whites in the Some College category are much more ideological on the right than those with a high school diploma only.

And this matters because this group is vastly overrepresented, basically everywhere. They’re solid majorities of the elites in both parties, of the media, of political Twitter. Though unscientific, when I’ve run polls of my Twitter following, which is roughly evenly balanced politically, more than 80 percent are whites with college degrees. This group is less than 30 percent of the American electorate.

If everything seems polarized these days, it’s probably because of the circles you run in. Not everyone is like this. And the people that aren’t—the multiracial working class—are wildly underrepresented in political media.

[...]

Racial issues do pull certainly Black voters left — particularly on the question of whether whites are advantaged and it being harder for Black Americans because of slavery. Economically liberal positions, like a $15 minimum wage or Medicare for All, also push Black voters left. But there are some issues that push them right, specifically the lately salient one of abortion or aggressive action on climate and the environment, a point of division between Black voters and Democratic elites that largely goes unnoticed.

[...]The moderate politics of nonwhite voters are a sign of hope for the future, not necessarily just for the Republican Party’s electoral chances. If you dislike polarization, nonwhite voters provide a needed antidote. That’s true not only in the way they serve as a moderating force in the Democratic Party, knocking down progressive candidates time after time after time. Nonwhite and working class voters are also poised to have a similar effect on the GOP, moving them off a high-class polarization that did the party no favors in 2022.

1 note

·

View note

Text

#1yrago The EU could give every European the #RightToRepair, but lobbyists will kill it unless we take action!

The European Union is at risk of missing a historic opportunity to bring the right to repair into legislation for the first time.

From Monday 10 December all EU member states will be called to vote on a package of regulations requiring manufacturers to make consumer and industrial products more repairable and energy-efficient in order to be approved in the EU single market.

However, pressure from industry lobbying, especially in key countries with a big manufacturing sector like Germany, Italy and the UK, has severely reduced the repair provisions in the proposed legislation. The latest draft lacks ambition and significantly limits the potential to make repairing appliances easier for all.

Luckily, all is not lost. We (The Restart Project) are urging everyone to support citizen-driven campaigning, which is proving fruitful in some of the key countries opposing the regulation. A German petition promoted by repair activists has created a real stir, garnering over 109,000 signatures and resulting in the Ministry of Environment releasing an action plan stating its full support for repair provisions. And in Italy, a petition demanding that the country stops blocking promising regulation has reached over 76,000 signatures and will be handed over to the Minister of Environment this week by community repair group Restarters Milano. But in the UK a similar petition has been overshadowed by Brexit negotiations. Meanwhile local community repair activists have come up with the Manchester Declaration, calling for more repairable products.

Citizens want longer lasting and easier to repair products and they get frustrated when things break much earlier than they should. There is fresh evidence that people want these changes, and specifically want governments to take an active role, as documented in recently published research by the Green Alliance in the UK and the EU Commission.

Why are these votes so important? For the first time these so-called “ecodesign” regulations take into account a product’s material efficiency over its whole lifecycle, not just the use phase. The new measures acknowledge that a huge amount of a product’s environmental impact comes from manufacturing. This means that being able to repair products is vital to extending their longevity and preventing unnecessary waste. It is estimated that with the new measures in place, by 2030 Europe alone could be saving 140 TWh of energy a year, 5% of its entire energy consumption.

So far attention on right to repair legislation has been mostly concentrated on the United States, with a focus on state-level measures to remove barriers for independent repairers to do their work. Yet it is now at the European Union level that we stand a chance to impact right to repair globally.

While the proposed measures only focus on repairability for appliances such as fridges, washing machines and dishwashers, this create a precedent, strongly increasing the odds that right to repair becomes a central aspect of future regulation for computers, vacuum cleaners and smartphones. Also, these measures are likely to trigger the emergence of similar requirements elsewhere around the world.

What makes a product repairable? In September the EU Commission drafted laws focusing on a few key issues: requiring availability for spare parts for a minimum number of years as well as access to repair information resources and, crucially, improving design to access key components in household appliances. As a result, repairing products could become easier, cheaper and less time-consuming.

This is in line with the demands of the emerging community repair movement, as reflected in initiatives like the Open Repair Alliance's International Repair Day. However, the latest revision of the proposals reflects the language and the demands of the industry, as summarised by a briefing of the European Environmental Board.

For example, rather than providing free access to repair information for all, the regulation could restrict access to registered, professional repairers who pay the manufacturers a fee, thus slamming the door on, among others, the growing movement of community repair initiatives. Also, appliance manufacturers wouldn’t be required to supply spare parts to third parties for the first two years from the introduction of a new model, potentially giving them initial complete control over repairs happening within the warranty period (even when not covered by warranty). Finally, the laudable initial inclusion of design requirements to simplify disassembly of appliances for repair is at risk of being replaced with a focus on effective dismantling for recycling at the end of life.

The ball is now in the member states’ court. Will they show some ambition and push for measures that will benefit all of their citizens, while contributing to creating local repair jobs and reducing the imbalance of power with manufacturers? Or will they bow to industry pressure and miss this rare chance for the European Union to demonstrate that it can lead the way in pushing for better standards for all?

https://boingboing.net/2018/12/04/the-eu-could-give-every-europe.html

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stephen Sachs on the wrong way to criticize originalism

Last week, Cass Sunstein wrote a column criticizing originalism and warning against an overly originalist nominee to the Supreme Court. A key excerpt:

For example, originalism could easily lead to the following conclusions:

1. States can ban the purchase and sale of contraceptives.

2. The federal government can discriminate on the basis of race — for example, by banning African Americans from serving in the armed forces, or by mandating racial segregation in the D.C. schools.

3. The federal government can discriminate against women — for example, by banning them from serving in high-level positions in the U.S. government.

4. States are permitted to bring back segregation, and they can certainly discriminate on the basis of sex.

5. Neither federal nor state governments have to respect the idea of one person, one vote; some people could be given far more political power than others.

6. States can establish Christianity as their official religion.

7. Important provisions of national environmental laws, including the Endangered Species Act and the Clean Water Act, are invalid.

The president should not nominate, and the Senate should not confirm, anyone who subscribes to these seven propositions — and originalists have to do real work to explain why they reject them.

Mike Ramsey and Mike Rappaport have both responded, with Ramsey pointing out that “not much work is needed” to explain why most of these consequences will not come to pass.

Mike Rappaport, meanwhile, asks: “Even if Sunstein were right about this, what would that prove?” He argues that various types of nonoriginalism could “easily lead” to these conclusions as well. “In fact, to the extent that nonoriginalism is about pursuing discretion on the part of judges to pursue what a good constitution would be – which is a big part of nonoriginalism – nonoriginalism clearly would allow these results.” (There is much more here.)

That provoked an extended response from my sometime co-author Steve Sachs on Twitter, which he has cleaned up so that I could re-post it here.

The “Originalism Causes Bad Things” argument that Sunstein makes has always bothered me. (Like Rappaport, I’ll set aside the question whether his seven claims are actually all true of originalism; I think not. Note also that many of the worst things on this list could only happen if democratic majorities vote for them, which seems pretty unlikely at this point.)

My worry is with the form of the originalism-causes-bad-things argument.

Sometimes the law has bad consequences. Is Sunstein denying that? (Is he a natural lawyer in disguise?) Sometimes even our law has bad consequences. That was surely true in 1788. But are those times wholly past? The danger in the originalism-causes-bad-things argument is that it risks being complacent about the moral state of things right now. People who are pro-life might not think our current practices are all that moral; neither might advocates for animals (of whom Sunstein is one), for prisoners, for drone victims, and so on. As Rappaport asks, has the living constitution really done away with every deep injustice that might give rise to similar questions? (“And Justice Breyer shall wipe away all tears from their eyes; … neither shall there be any more pain: for the former things are passed away.”)

The danger in suggesting that our law won’t produce desperately bad things–and in making the non-production of bad things a criterion for determining our law–is that it might lead us to overlook how bad things really are. H.L.A. Hart criticized the principle “that, at certain limiting points, what is utterly immoral cannot be law or lawful”: he worried

that it will serve to cloak the true nature of the problems with which we are faced and will encourage the romantic optimism that all the values we cherish ultimately will fit into a single system, that no one of them has to be sacrificed or compromised to accommodate another.

“All Discord Harmony not understood

All Partial Evil Universal Good”

We could imagine more entries in Sunstein’s parade of horribles. “States would be able to allow concentrated feedlots” might be worse for animals than even invalidating the Endangered Species Act; but nominees are never asked ominously about that in their hearings. That’s partly because there’s no good argument that feedlots are unconstitutional. But criticizing the lawyer telling you that (“you’re okay with animals’ suffering!”) is just killing the messenger. Sometimes legal rules really do take consequences into account. But Robert Bork’s America arguments blur the line between legal rules and policy preferences—which is an incredibly important line for lawyers and law professors to uphold!

Sunstein might respond that originalism is a choice: it’s a law reform project, one that happens to reform the law in a bad way. But that’s why I’ve argued that originalism isn’t law reform, that it’s what our law already requires. (And so has Will Baude, among others.) The idea that we face an ‘interpretive choice’–a choice of how to interpret our legal texts–assumes that the law itself takes no view on what to do with these texts. That view has been challenged, more than once. Or, to put it another way, paraphrasing an argument by Robert Nozick:

if legal texts fell into judges’ laps like manna from heaven, with no prior attachments to any particular modes of interpretation, then faced with these interpretive options we might have to choose among them on something like ordinary normative grounds. (“After all, what is to become of these things; what are we to do with them.”) But in the real world, legal texts aren’t just fortuitously appearing sets of words. They’re statutes and contracts and constitutions: entities that came into being as legal objects, that took form under a particular system’s legal rules, and that already made some contribution to the law simply by virtue of their adoption or enactment. They took on whatever legal content they had then, under the law as it stood at the time. So there’s no need to cast about for an interpretive theory at large. In the non-manna-from-heaven world in which legal instruments are produced by existing institutions, under existing systems of legal rules, there’s no separate process of interpretive choice for a theory of interpretive choice to be a theory of.

Sunstein can deny that originalism is the law–and has. But that should be the argument, not the various bad things that originalism would do if it were true. Because if it is true, then pointing out the defects of our existing law, and attributing them to others, has a very different valence.

To me, the problem isn’t (just) that non-originalist theories can cause bad things too. (Though that is a problem.) The problem is that it’s not clear what work ‘theory x causes bad things’ is supposed to do in legal argument. If X and Y were two competing theories of physics in the 1930s, and X would make it possible to build an atom bomb, the claim that ‘bombs are bad’ wouldn’t entail that ‘X is false.’ It doesn’t even suggest it, ceteris paribus. The two claims have nothing to do with one another; each rests on different grounds. In the same way, an argument ‘against X being the law’ is ambiguous: it could mean that ‘X isn’t our law now,’ or that ‘X is our law but shouldn’t be.’

So the question is how results matter to legal arguments. Is ‘results matter’ part of the nature of law? Does it follow from specific features of our law? (Which ones?) Is it a claim about legal method, like Mitch Berman’s reflective equilibrium theory? Is it a historical claim, like ‘Congress wouldn’t have wanted a statute with this consequence, so we’re probably misreading it’? Or is it just a law-reform or political-obligation claim, like ‘we have reason to change the law or even perhaps to disobey it’? Unfortunately, one reason why Sunstein’s column is so rhetorically effective is that it isn’t wholly clear on the point.

One last thought on Sunstein’s questions: in some sense, these are precisely the questions that senators shouldn’t ask. A televised hearing is a bad forum for airing deep and sophisticated theories of law. Nominees can’t speak well to controversial issues, and they’re explaining things to a largely nonlegal audience, both in and out of the room. The test that faces them isn’t whether their views are legally correct, but whether they sound legally correct on TV.

And senators are politicians; they may happen to take an interest in constitutional theory, but their incentives are to mind the next election. So the nomination process selects, as Sunstein notes, for those whose legal views already mostly cohere with a major-party platform. This is a bad feature of nomination hearings. “Robert Bork’s America”-type questions get misleading, platitudinous answers. Reynolds v. Sims, say, is far more controversial within the legal academy than with the general public; but who wants to try explaining that in a hearing?

All of this is to say: the difference between law and policy preferences is crucially important, and whatever undermines it is to be avoided (ceteris paribus).

Originally Found On: http://www.washingtonpost.com/news/volokh-conspiracy/wp/2017/02/07/stephen-sachs-on-the-wrong-way-to-criticize-originalism/

0 notes

Text

Stephen Sachs on the wrong way to criticize originalism

Last week, Cass Sunstein wrote a column criticizing originalism and warning against an overly originalist nominee to the Supreme Court. A key excerpt:

For example, originalism could easily lead to the following conclusions:

1. States can ban the purchase and sale of contraceptives.

2. The federal government can discriminate on the basis of race — for example, by banning African Americans from serving in the armed forces, or by mandating racial segregation in the D.C. schools.

3. The federal government can discriminate against women — for example, by banning them from serving in high-level positions in the U.S. government.

4. States are permitted to bring back segregation, and they can certainly discriminate on the basis of sex.

5. Neither federal nor state governments have to respect the idea of one person, one vote; some people could be given far more political power than others.

6. States can establish Christianity as their official religion.

7. Important provisions of national environmental laws, including the Endangered Species Act and the Clean Water Act, are invalid.

The president should not nominate, and the Senate should not confirm, anyone who subscribes to these seven propositions — and originalists have to do real work to explain why they reject them.

Mike Ramsey and Mike Rappaport have both responded, with Ramsey pointing out that “not much work is needed” to explain why most of these consequences will not come to pass.

Mike Rappaport, meanwhile, asks: “Even if Sunstein were right about this, what would that prove?” He argues that various types of nonoriginalism could “easily lead” to these conclusions as well. “In fact, to the extent that nonoriginalism is about pursuing discretion on the part of judges to pursue what a good constitution would be – which is a big part of nonoriginalism – nonoriginalism clearly would allow these results.” (There is much more here.)

That provoked an extended response from my sometime co-author Steve Sachs on Twitter, which he has cleaned up so that I could re-post it here.

The “Originalism Causes Bad Things” argument that Sunstein makes has always bothered me. (Like Rappaport, I’ll set aside the question whether his seven claims are actually all true of originalism; I think not. Note also that many of the worst things on this list could only happen if democratic majorities vote for them, which seems pretty unlikely at this point.)

My worry is with the form of the originalism-causes-bad-things argument.

Sometimes the law has bad consequences. Is Sunstein denying that? (Is he a natural lawyer in disguise?) Sometimes even our law has bad consequences. That was surely true in 1788. But are those times wholly past? The danger in the originalism-causes-bad-things argument is that it risks being complacent about the moral state of things right now. People who are pro-life might not think our current practices are all that moral; neither might advocates for animals (of whom Sunstein is one), for prisoners, for drone victims, and so on. As Rappaport asks, has the living constitution really done away with every deep injustice that might give rise to similar questions? (“And Justice Breyer shall wipe away all tears from their eyes; … neither shall there be any more pain: for the former things are passed away.”)

The danger in suggesting that our law won’t produce desperately bad things–and in making the non-production of bad things a criterion for determining our law–is that it might lead us to overlook how bad things really are. H.L.A. Hart criticized the principle “that, at certain limiting points, what is utterly immoral cannot be law or lawful”: he worried

that it will serve to cloak the true nature of the problems with which we are faced and will encourage the romantic optimism that all the values we cherish ultimately will fit into a single system, that no one of them has to be sacrificed or compromised to accommodate another.

“All Discord Harmony not understood

All Partial Evil Universal Good”

We could imagine more entries in Sunstein’s parade of horribles. “States would be able to allow concentrated feedlots” might be worse for animals than even invalidating the Endangered Species Act; but nominees are never asked ominously about that in their hearings. That’s partly because there’s no good argument that feedlots are unconstitutional. But criticizing the lawyer telling you that (“you’re okay with animals’ suffering!”) is just killing the messenger. Sometimes legal rules really do take consequences into account. But Robert Bork’s America arguments blur the line between legal rules and policy preferences—which is an incredibly important line for lawyers and law professors to uphold!

Sunstein might respond that originalism is a choice: it’s a law reform project, one that happens to reform the law in a bad way. But that’s why I’ve argued that originalism isn’t law reform, that it’s what our law already requires. (And so has Will Baude, among others.) The idea that we face an ‘interpretive choice’–a choice of how to interpret our legal texts–assumes that the law itself takes no view on what to do with these texts. That view has been challenged, more than once. Or, to put it another way, paraphrasing an argument by Robert Nozick:

if legal texts fell into judges’ laps like manna from heaven, with no prior attachments to any particular modes of interpretation, then faced with these interpretive options we might have to choose among them on something like ordinary normative grounds. (“After all, what is to become of these things; what are we to do with them.”) But in the real world, legal texts aren’t just fortuitously appearing sets of words. They’re statutes and contracts and constitutions: entities that came into being as legal objects, that took form under a particular system’s legal rules, and that already made some contribution to the law simply by virtue of their adoption or enactment. They took on whatever legal content they had then, under the law as it stood at the time. So there’s no need to cast about for an interpretive theory at large. In the non-manna-from-heaven world in which legal instruments are produced by existing institutions, under existing systems of legal rules, there’s no separate process of interpretive choice for a theory of interpretive choice to be a theory of.

Sunstein can deny that originalism is the law–and has. But that should be the argument, not the various bad things that originalism would do if it were true. Because if it is true, then pointing out the defects of our existing law, and attributing them to others, has a very different valence.

To me, the problem isn’t (just) that non-originalist theories can cause bad things too. (Though that is a problem.) The problem is that it’s not clear what work ‘theory x causes bad things’ is supposed to do in legal argument. If X and Y were two competing theories of physics in the 1930s, and X would make it possible to build an atom bomb, the claim that ‘bombs are bad’ wouldn’t entail that ‘X is false.’ It doesn’t even suggest it, ceteris paribus. The two claims have nothing to do with one another; each rests on different grounds. In the same way, an argument ‘against X being the law’ is ambiguous: it could mean that ‘X isn’t our law now,’ or that ‘X is our law but shouldn’t be.’

So the question is how results matter to legal arguments. Is ‘results matter’ part of the nature of law? Does it follow from specific features of our law? (Which ones?) Is it a claim about legal method, like Mitch Berman’s reflective equilibrium theory? Is it a historical claim, like ‘Congress wouldn’t have wanted a statute with this consequence, so we’re probably misreading it’? Or is it just a law-reform or political-obligation claim, like ‘we have reason to change the law or even perhaps to disobey it’? Unfortunately, one reason why Sunstein’s column is so rhetorically effective is that it isn’t wholly clear on the point.

One last thought on Sunstein’s questions: in some sense, these are precisely the questions that senators shouldn’t ask. A televised hearing is a bad forum for airing deep and sophisticated theories of law. Nominees can’t speak well to controversial issues, and they’re explaining things to a largely nonlegal audience, both in and out of the room. The test that faces them isn’t whether their views are legally correct, but whether they sound legally correct on TV.

And senators are politicians; they may happen to take an interest in constitutional theory, but their incentives are to mind the next election. So the nomination process selects, as Sunstein notes, for those whose legal views already mostly cohere with a major-party platform. This is a bad feature of nomination hearings. “Robert Bork’s America”-type questions get misleading, platitudinous answers. Reynolds v. Sims, say, is far more controversial within the legal academy than with the general public; but who wants to try explaining that in a hearing?

All of this is to say: the difference between law and policy preferences is crucially important, and whatever undermines it is to be avoided (ceteris paribus).

Originally Found On: http://www.washingtonpost.com/news/volokh-conspiracy/wp/2017/02/07/stephen-sachs-on-the-wrong-way-to-criticize-originalism/

0 notes

Text

The EU could give every European the #RightToRepair, but lobbyists will kill it unless we take action!

The European Union is at risk of missing a historic opportunity to bring the right to repair into legislation for the first time.

From Monday 10 December all EU member states will be called to vote on a package of regulations requiring manufacturers to make consumer and industrial products more repairable and energy-efficient in order to be approved in the EU single market.

However, pressure from industry lobbying, especially in key countries with a big manufacturing sector like Germany, Italy and the UK, has severely reduced the repair provisions in the proposed legislation. The latest draft lacks ambition and significantly limits the potential to make repairing appliances easier for all.

Luckily, all is not lost. We (The Restart Project) are urging everyone to support citizen-driven campaigning, which is proving fruitful in some of the key countries opposing the regulation. A German petition promoted by repair activists has created a real stir, garnering over 109,000 signatures and resulting in the Ministry of Environment releasing an action plan stating its full support for repair provisions. And in Italy, a petition demanding that the country stops blocking promising regulation has reached over 76,000 signatures and will be handed over to the Minister of Environment this week by community repair group Restarters Milano. But in the UK a similar petition has been overshadowed by Brexit negotiations. Meanwhile local community repair activists have come up with the Manchester Declaration, calling for more repairable products.

Citizens want longer lasting and easier to repair products and they get frustrated when things break much earlier than they should. There is fresh evidence that people want these changes, and specifically want governments to take an active role, as documented in recently published research by the Green Alliance in the UK and the EU Commission.

Why are these votes so important? For the first time these so-called “ecodesign” regulations take into account a product’s material efficiency over its whole lifecycle, not just the use phase. The new measures acknowledge that a huge amount of a product’s environmental impact comes from manufacturing. This means that being able to repair products is vital to extending their longevity and preventing unnecessary waste. It is estimated that with the new measures in place, by 2030 Europe alone could be saving 140 TWh of energy a year, 5% of its entire energy consumption.

So far attention on right to repair legislation has been mostly concentrated on the United States, with a focus on state-level measures to remove barriers for independent repairers to do their work. Yet it is now at the European Union level that we stand a chance to impact right to repair globally.

While the proposed measures only focus on repairability for appliances such as fridges, washing machines and dishwashers, this create a precedent, strongly increasing the odds that right to repair becomes a central aspect of future regulation for computers, vacuum cleaners and smartphones. Also, these measures are likely to trigger the emergence of similar requirements elsewhere around the world.

What makes a product repairable? In September the EU Commission drafted laws focusing on a few key issues: requiring availability for spare parts for a minimum number of years as well as access to repair information resources and, crucially, improving design to access key components in household appliances. As a result, repairing products could become easier, cheaper and less time-consuming.

This is in line with the demands of the emerging community repair movement, as reflected in initiatives like the Open Repair Alliance's International Repair Day. However, the latest revision of the proposals reflects the language and the demands of the industry, as summarised by a briefing of the European Environmental Board.

For example, rather than providing free access to repair information for all, the regulation could restrict access to registered, professional repairers who pay the manufacturers a fee, thus slamming the door on, among others, the growing movement of community repair initiatives. Also, appliance manufacturers wouldn’t be required to supply spare parts to third parties for the first two years from the introduction of a new model, potentially giving them initial complete control over repairs happening within the warranty period (even when not covered by warranty). Finally, the laudable initial inclusion of design requirements to simplify disassembly of appliances for repair is at risk of being replaced with a focus on effective dismantling for recycling at the end of life.

The ball is now in the member states’ court. Will they show some ambition and push for measures that will benefit all of their citizens, while contributing to creating local repair jobs and reducing the imbalance of power with manufacturers? Or will they bow to industry pressure and miss this rare chance for the European Union to demonstrate that it can lead the way in pushing for better standards for all?

Ugo Vallauri is a co-founder of The Restart Project, a London-based non-profit fixing our relationship with electronics.

https://boingboing.net/2018/12/04/the-eu-could-give-every-europe.html

56 notes

·

View notes