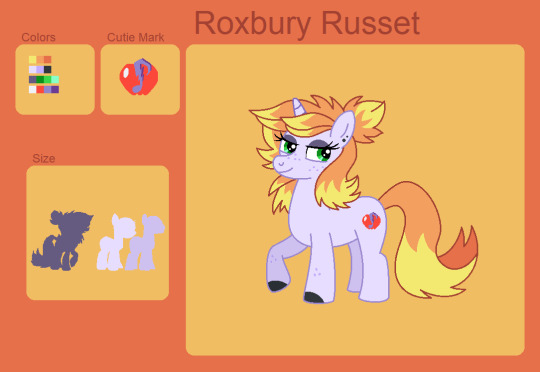

#roxbury russet

Photo

Designed for me by Tragedy-Kaz. (Original image)

Name: Roxbury Russet

Nickname(s): Roxie, Rox

Age: 24 years

Gender: Female

Species: Unicorn

Parents: Rarity and Braeburn (biological), Fancy Pants (step-father)

Siblings: Regal Rhyme (half-brother), Stayman Winesap (half-brother)

General Info:

Roxbury Russet, or "Roxie" as she prefers to be called, is Rarity's second child and Braeburn's first. The two of them had a shotgun marriage after Rarity got pregnant and later got divorced when Roxie was four after Braeburn realized that he wasn't attracted to mares that much. Being too young to fully understand what was going on, Roxie took it as her father not loving them anymore and has resented Braeburn ever since.

Feelings for her bio-dad aside, Roxie is a fun and firey young mare with an ear for music. She doesn't like others bringing up her ties to the Apple Family and would much rather be seen as a musician instead of some hick that grows apples.

Relationships:

While Roxie has a good relationship with her mother and step-dad, her relationship with her biological father Braeburn isn't all that great. She holds some resentment towards her bio dad for hurting her and mom all those years ago, and while Rarity has mostly forgiven him since then, Roxie isn't quite there yet.

Roxie has a half-brother in Appleloosa named Stayman Winesap, whom Roxie usually tries to avoid as she sees him as a reminder of what her dad did. Her two best friends in the world are an earth pony stallion named Bass Drop and a pegasus mare named Trash Talk. The three of them have formed a rock band in which Roxie is the guitarist.

Cutie Mark:

Roxie's cutie mark is a jagged music note in front of an apple, representing her talent for rock music as well as (to her annoyance) her connection to the Apple Family.

#barkerverse#my little pony friendship is magic#mlp: fim#mlp next gen#ref sheet#roxbury russet#rariburn

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nouveautés 25 Août

On va passer toute une bonne fin de semaine :

Cidre Sauvageon

- Pirouette

Cidre Collabo avec Revel Cider . Pomme, poire asiatique et sureau (assemblé avec un jus à base d'hibiscus, violette, gewurztraminer et prunes.

- Salange

Cidre d'inspiration Gose, au sel de mer et aux aromates.

Cidrerie Milton

- ROXBURY RUSSET

En plus d'apporter une belle structure de par ses tannins, cette variété fait ressortir des arômes d'agrumes et de fruits à chair blanches donnant un petit côté exotique au liquide

Brasseurs Sur Demande

- La Perla

Gose Mexicaine

La Fabrique Brasserie Artisanale

- Juliette

Bière surette au cassis.

0 notes

Text

It was a cool Sunday afternoon, much cooler than it got in Los Angeles. While Heath’s body was still attempting to adapt to the climate he reveled in the crisp air. It was one of the many things he missed about his own town. He grabbed an apple from the kitchen counter and made his way up the back stairwell. He found himself wandering the halls of his childhood home towards the library. He’d shown it to Carine during a tour of the house and she’d fell in love with it. There was no doubt in his mind that was exactly where she’d be. “Find anything worth taking home?” He questioned, biting into his roxbury russet. @student-of-history

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fire Blight Spreads Northward, Threatening Apple Orchards

GENEVA, N.Y. — Across the country, hundreds of kinds of apples were meticulously developed by orchardists over the last couple of centuries and then, as farms and groves were abandoned and commercial production greatly narrowed the number of varieties for sale, many were forgotten.Some of this horticultural biodiversity, though, has been nurtured by dedicated growers who want to preserve the forgotten flavors and other traits of apples from the past. For example, some of the best apples ever developed for baking pies are no longer grown commercially, experts say, but are still thriving in heirloom orchards.“They are a piece of our history as a variety and part of our cultural identity,” said Mark Richardson, director of horticulture at the Tower Hill Botanic Garden in Boylston, Mass. “But also some of these varieties may be important for breeding the next generation. They are an insurance policy against a catastrophe.”A burgeoning threat is coming for apples, though, both of the historical varieties and the popular ones grown in the orchards today. A disease called fire blight, easily managed for a long time in apple and pear orchards, is becoming more virulent as the climate changes and as growers alter the way the trees are configured to produce higher yields. Some researchers say newer varieties may be more vulnerable, too. It is another example of threats to the nation’s fruit crops, as citrus greening has hammered Florida’s orange groves and a fungus called Tropical Race 4 has devastated the world’s banana plantations.“Commercial apples are getting hit fairly hard by fire blight,” said Kerik D. Cox, a plant pathologist who has studied the disease for a decade at Cornell College of Agriculture and Life Sciences here. “And the intensity of it appears to be new.”As they walk down a row of small and thin apple trees, with large dark red apples hanging on them like Christmas bulbs, Dr. Cox and a graduate student, Anna Wallis, point out a shriveled, dark brown branch on one of them.The blight — caused by the bacterium erwinia amylovora — is native to the United States and predates the introduction of apple trees to North America. Apple and pear growers have long managed the disease, by trimming dead branches and in recent decades, spraying antibiotics like Streptomycin. But the blight is becoming resistant to the antibiotics, some say, and has become more aggressive, wiping out hundreds or even thousands of trees in some places.The blight is spreading to places where it had not been seen before, into New York’s Champlain Valley and parts of Maine for example.Tower Hill Botanic Garden was forced in November to raze its orchard of 238 heirloom trees — two each of 119 antique varieties. The orchard is dedicated to apples developed in this country, Europe and elsewhere long ago.One of the varieties, the Roxbury Russet, dates back to the mid-17th century, and is believed to be the oldest apple variety cultivated in the United States.In an effort to keep the ancient lineage of the orchard from disappearing, the scionwood — cuttings from recent aboveground growth — was grafted onto new blight-resistant root stock. The new tree grafts will grow for a year at an orchard in Maine, and then will be returned for planting in 2021.Orchards like the one at Tower Hill — there are fewer than a dozen in the country, experts say — have been likened to the Svarlbard Global Seed Vault, a concrete facility storing nearly one million seed species on the side of a mountain on a Norwegian island.The genetics of these trees may exist nowhere else and could someday be used to create new commercial varieties because of their flavor or resistance to disease and pests. Keeping the actual trees alive by growing successive generations through cloning and grafting is the only way to assure their lineage. That is because a seed from a particular tree may not contain all of the traits of the variety because one of the parents is unknown.Tower Hill had never seen fire blight during the bloom season, which provides a potent pathway for infection, until 2011. “We get a combination of weird and tragic weather, these days, variable and unpredictable,” Dr. Cox said.Unusual spikes in temperature and more wet weather form ideal conditions for the bacterium. While May temperatures in this part of the Northeast used to rise more gradually and more uniformly, that dynamic started changing about 20 years ago and now some days in that month can spike into the 70s, Dr. Cox said. In May 2010, temperatures soared into the 80s.“Fire blight enters the tree through the flower and if it lands on a flower in bloom with temps in the 60s, it can’t enter,” Mr. Richardson of Tower Hill said. “But if it’s over 75, the conditions are right for the spore to enter the flower and get into the vascular system and it moves through the orchard faster.”Honeybees and other insects then spread the disease as they pollinate apple blossoms. At warmer temperatures, fire blight is much more virulent. “It has the ability to kill a tree in a single season,” Mr. Richardson said.“We have a lot of trees that have been mutilated,” he added. “And they are succumbing to old age because of the presence of fire blight, which weakens them.” At optimum temperatures, the bacteria double in volume every 20 minutes, Dr. Cox said.“I never thought about fire blight, it was an issue for the South,” said John P. Bunker, a long time apple grower farther north in Palermo, Maine, who identifies and preserves forgotten heirloom varieties across the country. “But 10 years ago, there was a big fire blight outbreak and suddenly it was here. I have preservation orchards all over my property, hundreds of trees and I had never, ever seen it and all of a sudden I was seeing it.”What makes the ecology of the disease even more challenging to solve and address is that while a warmer world is a big part of the emerging problem, there are other factors that may be contributing to ideal conditions for an outbreak.Apple orchards these days are a very different creature than they used to be. “People climbing apple trees and harvesting fruit with ladders, that’s gone,” Dr. Cox said. “It’s now about making an apple like a grape, where you can walk by and pick the fruit right off the tree.”Many modern commercial apple trees are planted in what’s called a high density trellis system. They top out at about six to eight feet and are narrow, like a sapling. Yet, fertilizers can push this waifish modern tree to grow about 50 full-size apples, compared to as many as 300 or so on the old-style trees. But instead of some 300 trees to an acre spaced about 10 feet apart, trees are planted 18 to 24 inches apart and there are 1,500 or so trees to an acre.The trellis-style orchard increases product and profit. A few decades ago, apple growers harvested 200 to 300 bushels of apples to the acre. The goal now is 2,000 bushels an acre, Dr. Cox said.The trellis configuration makes it difficult to manage fire blight. “The old-style trees that we used to grow were big and had tons of branches and the bacteria couldn’t move through the tree very well,” said George Sundin, a plant pathologist at Michigan State University, where fire blight is also a growing problem. In these new trees, “the branches are smaller and it’s a short distance from the branch to the tree and down to the roots.”Managed by cutting out infection, fire blight rarely killed trees in the old days, but now can wipe out hundreds or thousands in a month or two. It can spread from orchard to orchard through the wind or by insects carrying the disease.Another contributing factor may be that the new apple trees are not as resistant to disease. “They are the equivalent of a caged chicken, planting them in crowded conditions and pushing them with nutrients to grow 50 or more apples to a tree,” Dr. Cox said.And because many more trees are being planted, tree growers are rushing to fill orders. “Nurseries can’t grow trees fast enough and quality is compromised,” Dr. Cox said.Moreover, modern varieties may also play a role. “So is it primarily climate change, or is it that they are packed together?” Dr. Cox asked. “Or is it the new varieties — such as Evercrisp and Gala — which may be more susceptible? That’s what we are trying to find out.”One answer may be growing in the National Apple Collection, not far from Dr. Cox’s research grove. Managed by the Department of Agriculture, it is the largest collection of apple genetics on the planet. There are some 6,000 trees, wild and domestic, with 55 species and hybrids from around the world, including Central Asia where the apple originated.These genes are so critical to the future of apples that cuttings from the trees are shipped to the National Laboratory for Genetic Resources Preservation in Fort Collins, Colo., where they are preserved in liquid nitrogen and stored in a vault.One of the ways these trees may earn their keep is by helping out in the battle against fire blight.“We are looking at genes from wild species for fire blight resistance,” said Awais Khan, a plant pathologist at Cornell who is doing this work. It might take 25 years of breeding to create fire blight resistant apple trees, he said, “but there are ways we can speed up the process, so maybe 10 or 15 years.”

Source link

Read the full article

0 notes

Photo

Earky morning harvest! 2+ lbs of Roxbury Russet! Grown from seed! (at Roxbury, Massachusetts) https://www.instagram.com/p/B2_pAiyAsM6/?igshid=19vgkh5zt6dwj

0 notes

Photo

Dragon: Roxbury - Coatl Skydancer XXY Female

(Skydancer scroll applied on 2019-02-11)

(Bee scroll applied on 2019-02-11)

(Opal scroll applied on 2019-02-11)

Purchased For: 25 gems

Hatched On: 2018-06-10

ID: 42363753

Parentage: Maplesugar/Sable

Flight: Fire

Primary: Tarnish Metallic

Secondary: Tarnish Shimmer Bee

Tertiary: Soil Ghost Opal

Eyes: Common

Comments: Purchased as a mate for Egremont. She, like he, has been named after a russet apple variety.

Apparel:

Peace Dove

Blushing Pink Rose

Sakura Lei, Corsage, Tail Lei, Flower Crown, Flowerfall, and Wing Garlands

Kiwi Plumed Anklets, Corsage, Tuft, and Cover

Familiar: Maren Fisher

Progeny Testing:

[Test] Egremont

Broods:

Nested with Egremont on 2019-02-11, 3 eggs [Clutch]

Bred with Egremont on 2019-03-25, 3 eggs [Clutch]

Clutched with Egremont on 2019-05-09, 4 eggs [Clutch]

Matched with Egremont on 2019-08-18, 2 eggs [Clutch]

Paired with Egremont on 2019-11-03, 3 eggs [Clutch]

Mated with Egremont on 2019-12-28, 3 eggs [Clutch]

Crossed with Egremont on 2020-03-06, 3 eggs [Clutch]

Nested with Egremont on 2020-04-23, 2 eggs [Clutch]

Bred with Egremont on 2020-06-15, 2 eggs [Clutch]

Clutched with Egremont on 2020-08-01, 2 eggs [Clutch]

Matched with Egremont on 2020-09-21, 3 eggs [Clutch]

Joined with Egremont on 2020-11-23, 4 eggs [Clutch]

Paired with Egremont on 2021-02-27, 1 egg [Clutch]

Mated with Egremont on 2021-05-30, 4 eggs [Clutch]

Crossed with Egremont on 2021-08-31, 3 eggs [Clutch]

Nested with Egremont on 2021-11-29, 3 eggs [Clutch]

Bred with Egremont on 2022-02-17, 3 eggs [Clutch]

Clutched with Egremont on 2022-06-05, 5 eggs [Clutch]

Matched with Egremont on 2022-08-23, 2 eggs [Clutch]

Joined with Egremont on 2022-11-29, 3 eggs [Clutch]

Paired with Egremont on 2023-03-19, 3 eggs [Clutch]

Mated with Egremont on 2023-06-25, 3 eggs [Clutch]

Crossed with Egremont on 2023-10-04, 2 eggs [Clutch]

Nested with Egremont on 2024-01-11, 3 eggs [Clutch]

Bred with Egremont on 2024-04-11, 3 eggs [Clutch]

#Roxbury Dragon#Dragon Queen#Dragon Record#Skydancer Female#Skydancer Breed#Brown Pool#XXY#Tarnish#Metallic#Metallic Tarnish#Bee#Bee Tarnish#Soil#Opal#Opal Soil#Fire Flight#Common#Maren Fisher

0 notes

Text

Fire Blight Spreads Northward, Threatening Apple Orchards

GENEVA, N.Y. — Across the country, hundreds of kinds of apples were meticulously developed by orchardists over the last couple of centuries and then, as farms and groves were abandoned and commercial production greatly narrowed the number of varieties for sale, many were forgotten.

Some of this horticultural biodiversity, though, has been nurtured by dedicated growers who want to preserve the forgotten flavors and other traits of apples from the past. For example, some of the best apples ever developed for baking pies are no longer grown commercially, experts say, but are still thriving in heirloom orchards.

“They are a piece of our history as a variety and part of our cultural identity,” said Mark Richardson, director of horticulture at the Tower Hill Botanic Garden in Boylston, Mass. “But also some of these varieties may be important for breeding the next generation. They are an insurance policy against a catastrophe.”

A burgeoning threat is coming for apples, though, both of the historical varieties and the popular ones grown in the orchards today. A disease called fire blight, easily managed for a long time in apple and pear orchards, is becoming more virulent as the climate changes and as growers alter the way the trees are configured to produce higher yields. Some researchers say newer varieties may be more vulnerable, too.

It is another example of threats to the nation’s fruit crops, as citrus greening has hammered Florida’s orange groves and a fungus called Tropical Race 4 has devastated the world’s banana plantations.

“Commercial apples are getting hit fairly hard by fire blight,” said Kerik D. Cox, a plant pathologist who has studied the disease for a decade at Cornell College of Agriculture and Life Sciences here. “And the intensity of it appears to be new.”

As they walk down a row of small and thin apple trees, with large dark red apples hanging on them like Christmas bulbs, Dr. Cox and a graduate student, Anna Wallis, point out a shriveled, dark brown branch on one of them.

The blight — caused by the bacterium Erwinia amylovora — is native to the United States and predates the introduction of apple trees to North America. Apple and pear growers have long managed the disease, by trimming dead branches and in recent decades, spraying antibiotics like Streptomycin. But the blight is becoming resistant to the antibiotics, some say, and has become more aggressive, wiping out hundreds or even thousands of trees in some places.

The blight is spreading to places where it had not been seen before, into New York’s Champlain Valley and parts of Maine for example.

Tower Hill Botanic Garden was forced in November to raze its orchard of 238 heirloom trees — two each of 119 antique varieties. The orchard is dedicated to apples developed in this country, Europe and elsewhere long ago.

One of the varieties, the Roxbury Russet, dates back to the mid-17th century, and is believed to be the oldest apple variety cultivated in the United States.

In an effort to keep the ancient lineage of the orchard from disappearing, the scionwood — cuttings from recent aboveground growth — was grafted onto new blight-resistant root stock. The new tree grafts will grow for a year at an orchard in Maine, and then will be returned for planting in 2021.

Orchards like the one at Tower Hill — there are fewer than a dozen in the country, experts say — have been likened to the Svarlbard Global Seed Vault, a concrete facility storing nearly one million seed species on the side of a mountain on a Norwegian island.

The genetics of these trees may exist nowhere else and could someday be used to create new commercial varieties because of their flavor or resistance to disease and pests. Keeping the actual trees alive by growing successive generations through cloning and grafting is the only way to assure their lineage. That is because a seed from a particular tree may not contain all of the traits of the variety because one of the parents is unknown.

Tower Hill had never seen fire blight during the bloom season, which provides a potent pathway for infection, until 2011. “We get a combination of weird and tragic weather, these days, variable and unpredictable,” Dr. Cox said.

Unusual spikes in temperature and more wet weather form ideal conditions for the bacterium. While May temperatures in this part of the Northeast used to rise more gradually and more uniformly, that dynamic started changing about 20 years ago and now some days in that month can spike into the 70s, Dr. Cox said. In May 2010, temperatures soared into the 80s.

“Fire blight enters the tree through the flower and if it lands on a flower in bloom with temps in the 60s, it can’t enter,” Mr. Richardson of Tower Hill said. “But if it’s over 75, the conditions are right for the spore to enter the flower and get into the vascular system and it moves through the orchard faster.”

Honey bees and other insects then spread the disease as they pollinate apple blossoms. At warmer temperatures, fire blight is much more virulent. “It has the ability to kill a tree in a single season,” Mr. Richardson said.

“We have a lot of trees that have been mutilated,” he added. “And they are succumbing to old age because of the presence of fire blight, which weakens them.” At optimum temperatures, the bacteria double in volume every 20 minutes, Dr. Cox said.

“I never thought about fire blight, it was an issue for the South,” said John P. Bunker, a long time apple grower farther north in Palermo, Maine, who identifies and preserves forgotten heirloom varieties across the country. “But 10 years ago, there was a big fire blight outbreak and suddenly it was here. I have preservation orchards all over my property, hundreds of trees and I had never, ever seen it and all of a sudden I was seeing it.”

What makes the ecology of the disease even more challenging to solve and address is that while a warmer world is a big part of the emerging problem, there are other factors that may be contributing to ideal conditions for an outbreak.

Apple orchards these days are a very different creature than they used to be. “People climbing apple trees and harvesting fruit with ladders, that’s gone,” Dr. Cox said. “It’s now about making an apple like a grape, where you can walk by and pick the fruit right off the tree.”

Many modern commercial apple trees are planted in what’s called a high density trellis system. They top out at about six to eight feet and are narrow, like a sapling. Yet, fertilizers can push this waifish modern tree to grow about 50 full-size apples, compared to as many as 300 or so on the old-style trees. But instead of some 300 trees to an acre spaced about 10 feet apart, trees are planted 18 to 24 inches apart and there are 1,500 or so trees to an acre.

The trellis-style orchard increases product and profit. Many more premium apples are produced in the new-style orchard, some experts say. A few decades ago, apple growers harvested 200 to 300 bushels of apples to the acre and about 25 bushels were the highest grade. The goal now is 2,000 bushels an acre of premium apples, Dr. Cox said.

The trellis configuration makes it difficult to manage fire blight. “The old-style trees that we used to grow were big and had tons of branches and the bacteria couldn’t move through the tree very well,” said George Sundin, a plant pathologist at Michigan State University, where fire blight is also a growing problem. In these new trees, “the branches are smaller and it’s a short distance from the branch to the tree and down to the roots.”

Managed by cutting out infection, fire blight rarely killed trees in the old days, but now can wipe out hundreds or thousands in a month or two. It can spread from orchard to orchard through the wind or by insects carrying the disease.

Another contributing factor may be that the new apple trees are not as resistant to disease. “They are the equivalent of a caged chicken, planting them in crowded conditions and pushing them with nutrients to grow 50 or more apples to a tree,” Dr. Cox said.

And because many more trees are being planted, tree growers are rushing to fill orders. “Nurseries can’t grow trees fast enough and quality is compromised,” Dr. Cox said.

Moreover, modern varieties may also play a role. “So is it primarily climate change, or is it that they are packed together?” Dr. Cox asked. “Or is it the new varieties — such as Evercrisp and Gala — which may be more susceptible? That’s what we are trying to find out.”

One answer may be growing in the National Apple Collection, not far from Dr. Cox’s research grove. Managed by the Department of Agriculture, it is the largest collection of apple genetics on the planet. There are some 6,000 trees, wild and domestic, with 55 species and hybrids from around the world, including Central Asia where the apple originated.

These genes are so critical to the future of apples that cuttings from the trees are shipped to the National Laboratory for Genetic Resources Preservation in Fort Collins, Colo., where they are preserved in liquid nitrogen and stored in a vault.

One of the ways these trees may earn their keep is by helping out in the battle against fire blight.

“We are looking at genes from wild species for fire blight resistance,” said Awais Khan, a plant pathologist at Cornell who is doing this work. It might take 25 years of breeding to create fire blight resistant apple trees, he said, “but there are ways we can speed up the process, so maybe 10 or 15 years.”

Sahred From Source link Science

from WordPress http://bit.ly/2YhaNtm

via IFTTT

0 notes

Photo

ROX is a modern expression of Roxbury Russet apples. pure & electric. past, present, & future. https://ift.tt/2Eq8XA8

0 notes

Photo

Last heirloom apple from @scottfarmvt until next year. This a Roxbury Russet, some say the oldest American variety, sweet and lightly tart, crunchy as a coconut.

0 notes

Photo

Decided to add this Rarity x Fancy Pants kid to my main MLP next gen universe. If you've been following me on DeviantArt for a while, you may recall that he was originally part of my Disliked Ships AU (which is currently in the process of being revamped) because I originally wasn't a big fan of RariPants.

But then, something happened over the years. It grew on me. I think maybe the reason I didn't like it originally is because all the foals for it looked so GENERIC. Almost all of them are a white unicorn with either a blue or purple mane. I'm not saying that people are bad to design them, as some of them are great, but it gets kinda old after a while. I decided to stray away from that with this guy's design by mixing Fancy's colors with that of Rarity's parents to make a more original palette.

--------------------

Name: Regal Rhyme

Nickname(s): Regal Splendor (actual name)

Age: 18 years

Gender: Male

Species: Unicorn

Parents: Rarity and Fancy Pants

Siblings: Roxbury Russet (half-sister), Brilliance (brother)

General Info:

Regal Splendor, or Regal Rhyme as he prefers to be called, was never into fashion or the high life like his parents. He ended up discovering his talent in poetry after being introduced to it by a good friend's mother and later changed part of his name to better match his profession. Rhyme can often be seen sipping from a cup of coffee or hanging out at his local poetry club. The guy is pretty chill most of the time, and often looks at things like "Okay, whatever."

Relationships:

Regal Rhyme has a good relationship with most of his parents, both of them whole heartedly supporting his profession. His closest friends are Maud Pie's son Timber Stone and Applejack's son Harrison Cider. Timber is a fun stallion to hang out with and his mother Maud was the pony that introduced him to his love of poetry. Harrison is a very calm and easygoing stallion that Rhyme enjoys hanging out with, and lately he's noticed that Harrison might have eyes on a pony they occasionally meet in Canterlot...

Cutie Mark:

Regal Rhyme's cutie mark is a roll of parchment with a writing quill, representing his talent of writing poetry.

#barkerverse#my little pony friendship is magic#mlp: fim#mlp next gen#ref sheet#regal rhyme#raripants#fancity

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Apple Hunting Season by Thomas Christopher

This is the time of year when I start scouting for apple trees. Neglected, venerable trees full of fruit that nobody wants. Not shiny, red, and flawless, ready to be popped into a lunch box. Nor even the big, sweet fruits bred for baking. The apples I want can be rough-coated, gnarled, and even a little scabby. They’re tart and tannic, puckering your mouth at the first bite. Powerfully flavorful. Perfect, in other words, for making hard cider.

That – hard cider making – used to be a tradition in my part of the world, southern New England. From Virginia north, but especially in the northeastern states, hard cider was the vin de pays, the local drink with a definite regional character. In part that was a reflection of the regional nature of apple growing. Virginia, for example, was ‘Hewe’s Crab’ country when it came to cider making; in New Jersey, the apples of choice were ‘Winesap’ and ‘Harrison’. New England boasted many fine cider apples; the standards included ‘Roxbury Russet,’ ‘Golden Russet’ and also ‘Baldwin’.

I had heard mentions in passing of hard cider from my father, a Connecticut native who associated it with haying time on relatives’ farms. But my first real encounter with it came in the library of the New York Botanical Garden. One day, while prowling the stacks, I came on a book published in 1911: The cider makers’ hand book : a complete guide for making and keeping pure cider by J.M. Trowbridge. This volume not only told the reader every detail of how to make hard cider, it made clear why you should want to:

“A pure article of cider, skillfully made from select fruit in perfect condition, should have perfect limpidity and brightness, even to sparkling in the glass… It should be fragrant so that when a bottle is freshly opened and poured into glasses an agreeable, fruity perfume will arise and diffuse itself though the apartment… It should have mild pungency, and feel warming and grateful to the stomach, the glow diffusing itself gradually and agreeably throughout the whole system, and communicating itself to the spirits…and it should leave in the mouth an abiding agreeable flavor of some considerable duration, as of rare fruits and flowers.”

I began collecting apples, and with an antique cider press rescued from a friend’s barn, I pressed my first batch, fermenting it down to dryness in glass carboys. I siphoned it into bottles and corked them. Six months later the cider was straw golden, clear, sparkling, and smelling and tasting of the apples’ very essence.

I’ve since updated my equipment, purchasing an electric-powered, Italian fruit crusher which I share with a farmer in western Massachusetts. The farmer, in return, allows me to use his hydraulic cider press. With these devices, I get far more juice from a bushel of fruit, which is good because appropriate fruit is harder and harder to find as the old trees die off and are replaced by less intensely flavored modern cultivars. Every year I have to travel farther afield to find my fruit. What better excuse, though, for exploring back roads while enjoying the fall foliage?

Apple Hunting Season originally appeared on Garden Rant on September 4, 2017.

from Garden Rant http://gardenrant.com/2017/09/apple-hunting-season.html

0 notes

Text

Apple Hunting Season by Thomas Christopher

This is the time of year when I start scouting for apple trees. Neglected, venerable trees full of fruit that nobody wants. Not shiny, red, and flawless, ready to be popped into a lunch box. Nor even the big, sweet fruits bred for baking. The apples I want can be rough-coated, gnarled, and even a little scabby. They’re tart and tannic, puckering your mouth at the first bite. Powerfully flavorful. Perfect, in other words, for making hard cider.

That – hard cider making – used to be a tradition in my part of the world, southern New England. From Virginia north, but especially in the northeastern states, hard cider was the vin de pays, the local drink with a definite regional character. In part that was a reflection of the regional nature of apple growing. Virginia, for example, was ‘Hewe’s Crab’ country when it came to cider making; in New Jersey, the apples of choice were ‘Winesap’ and ‘Harrison’. New England boasted many fine cider apples; the standards included ‘Roxbury Russet,’ ‘Golden Russet’ and also ‘Baldwin’.

I had heard mentions in passing of hard cider from my father, a Connecticut native who associated it with haying time on relatives’ farms. But my first real encounter with it came in the library of the New York Botanical Garden. One day, while prowling the stacks, I came on a book published in 1911: The cider makers’ hand book : a complete guide for making and keeping pure cider by J.M. Trowbridge. This volume not only told the reader every detail of how to make hard cider, it made clear why you should want to:

“A pure article of cider, skillfully made from select fruit in perfect condition, should have perfect limpidity and brightness, even to sparkling in the glass… It should be fragrant so that when a bottle is freshly opened and poured into glasses an agreeable, fruity perfume will arise and diffuse itself though the apartment… It should have mild pungency, and feel warming and grateful to the stomach, the glow diffusing itself gradually and agreeably throughout the whole system, and communicating itself to the spirits…and it should leave in the mouth an abiding agreeable flavor of some considerable duration, as of rare fruits and flowers.”

I began collecting apples, and with an antique cider press rescued from a friend’s barn, I pressed my first batch, fermenting it down to dryness in glass carboys. I siphoned it into bottles and corked them. Six months later the cider was straw golden, clear, sparkling, and smelling and tasting of the apples’ very essence.

I’ve since updated my equipment, purchasing an electric-powered, Italian fruit crusher which I share with a farmer in western Massachusetts. The farmer, in return, allows me to use his hydraulic cider press. With these devices, I get far more juice from a bushel of fruit, which is good because appropriate fruit is harder and harder to find as the old trees die off and are replaced by less intensely flavored modern cultivars. Every year I have to travel farther afield to find my fruit. What better excuse, though, for exploring back roads while enjoying the fall foliage?

Apple Hunting Season originally appeared on Garden Rant on September 4, 2017.

from Garden Rant http://ift.tt/2vYfM2u

0 notes

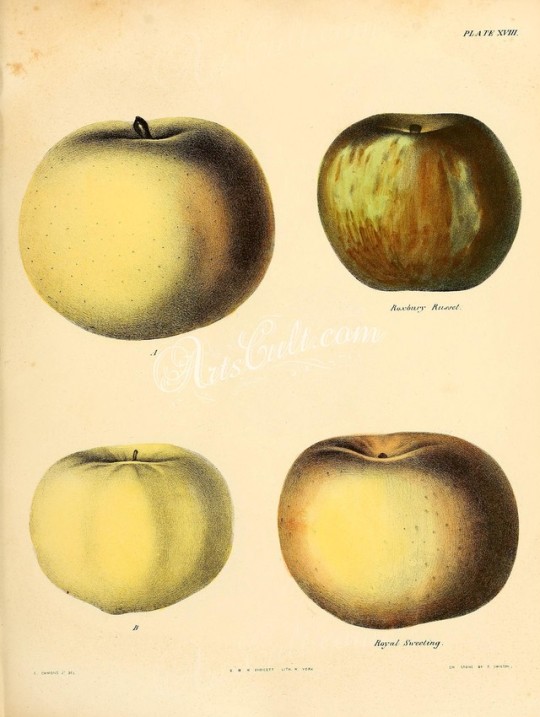

Photo

Roxbury Russet Apple, Royal Sweeting Apple - high resolution image from old book.

0 notes

Photo

Day 90 - 100 Day Project. Roxbury Russets Ripening. The Roxbury Russet is thought to be the oldest variety of apple bred in the United States. Not the prettiest apple, but it makes great apple sauce and cider.

#roxbury russet#apple#photographers on tumblr#original photographers#100 day project#apple tree#fruit#leaves#bokeh#ripening#Minolta#Rokkor#Guy Biechele

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Apples in the News

Roxbury's long-gone orchards are well known in local history circles. The Roxbury Russet apple and Bartlett Pear both hail from our long-ago days as an agricultural community, and it's not uncommon to see a few Russets planted at historical sites. But until recently, people who aren't history buffs wouldn't have heard of these fruits or known that Roxbury was once known far and wide for its orchards.

That seems to be changing. Across the country, grocery stores and restaurants now feature all sorts of artisanal and heirloom foods that would have been completely foreign to most eaters 20 years ago. So it's no surprise that the Roxbury Russet, in particular, is making something of a comeback.

Fans of apple lore and Roxbury history will be pleased to see that this attention has put the apple in the news, propelled by the release of a new book titled "Apples of Uncommon Character." The book, which has led to stories in the Boston Globe and on WBUR, is getting positive reviews so far. I'm sure it will be a worthy addition to any local historian's bookshelf.

With apple picking season upon us, now's a great time to go out pick a few Roxbury Russets of your own. There are a handful of trees around Roxbury, but most are privately owned or otherwise not suitable for public consumption. The nearest commercial orchard I could find that advertises the apple is Clarkdale Farm in Deerfield. The UMass Amherst Cold Spring Orchard also sells the Russet, which is available in the first half of October.

Of course, most apple buffs also know that apples were prized less for their fruit than for their use to make hard cider. West County Cider in Colerain, MA, has been making some excellent single-apple varietals in recent years. Luckily for us, one of those is the Roxbury Russet. The cider can sometimes be found at Blanchard's in JP. If it's not their, they may be able to special order it for you. West County doesn't have much of a website, but they did make a pretty good YouTube video a couple of years ago that gives a good overview of cider production.

If you've got a plot of land with some sun and you're hoping to grow apples, you're also in luck. A number of vendors sell Roxbury Russets, including Fedco, Stark Bros., Trees of Antiquity, Maple Valley, and Century Farm.

Whether you prefer to read about apples, eat them raw, turn them into pies, or drink a glass of cider, it's great to see the Roxbury's history as an apple producing town getting some press. Happy fall!

1 note

·

View note