#relationships with men will always be harmful to women not bc of the relationship structure but bc of the men

Text

if we wanted to get very spicy and kick the discourse hornet nest we might assert that okay, if transandrophobia isn't a real thing (?) then you might say trans men experience transmisogyny. not indirect or falsely directed transmisogyny, but transmisogyny. as in misogyny specific to the general trans experience.

how do you feel about that?

if you feel that takes away from the language of trans women available to discuss their specific experiences, because transmisogyny is a term for trans women, then okay.

what do you suggest for trans men to use to theorize our experiences?

anti-transmasculinity? is that fine? and why? /gen

part of the discourse here is a pushback on the infantilization and patronizing tone people take with trans men or talking over the transmasculine experience in general.

that's all.

also for the record I am genuinely not emotionally invested in this issue or reactive about it. I hold a lot of grace for fellow trans people's emotions and general attitudes intercommunity cuz man, the community is dealing with a lot.

and if something like "Baeddel" is a slur and not a term self-claimed by a group of anti-civ anti-social anarchist-leaning trans women that leaned into high-control cult territory then I'll stop using it.

(edited to change language of similarity bc harm levels were different)

there is also a lot of damage in the online trans community due to the "AFAB only" FB group cults run by trans TERFs in the last 5 years, who were responsible for the general reactive vitriol towards "theyfabs"

my main issue with the Baeddels I interacted with is that they were mean, dismissive, and genuinely seemed to be involved in culty dynamics that lead to increased community strife & increased risk for interpersonal abusive behavior. I don't think they deserved high levels of vitriol, backlash, cancellation or other transmisogynist abuse that unfortunately only made those other problems worse and further fragmented the community.

I still am friends with a few trans women who philosophically remain in this camp, and respect their views even though we disagree. unfortunately, both of these women are susceptible to and currently in varying degrees of abusive/high control relationships. They have not asked for help or indicated wanting intervention so I stay in my lane and provide affirmation & warmth when needed, but it does confirm my biases there.

the AFAB TERF groups were actively harmful to trans women and trans men, due to the way they weaponized transmisogyny, manipulated, groomed and emotionally abused trans men, and contributed to the wave of de-transitioner narratives actively in use by cis power structures.

so they're not equivalent. and I can see why people might suspect the axis of analysis of transandrophobia might be TERFy or something...its not IMO because those groups tended to endorse self-hatred and barely identify as trans, and still engage in high levels of man-hating and "androphobia"

WHICH BY THE WAY almost always comes back around to harm trans women as well as trans men.

reading bell hooks' The Will to Change on masculinity informs my position here.

so if you're looking to pick a fight, meh. i'm open to good faith discourse oriented towards restorative justice tho.

#transandrophobia#transmisogyny#discourse#trans discourse#long post#all of this is informed by people i actually know as well as general observation

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

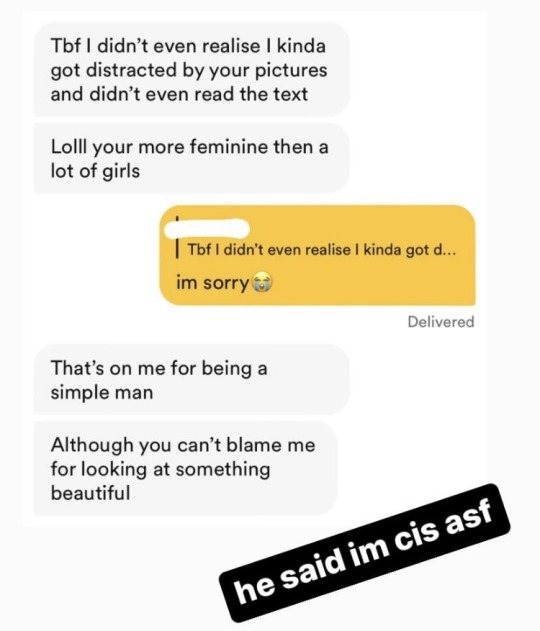

I will start with a disclaimer: I do not want any hate towards the creator in case someone knows who she is. This is in no means meant to hate her, I just want to make a point about femininity and gender. She is a trans woman and this is a convo she posted with a man she likes. I also want to underline that I still have a lot to learn and I am doing as much as I can to stop spreading harmful behaviours I sometimes still have to other women.

Growing up I had a difficult relationship with gender roles. I remember trying so hard to look more boyish to assert my power, felt as if anything feminine (connected to women) was somehow a bit stupid and not helping towards women (I was already a feminist but at the time I was wrong about how). Later I realised I liked being a more feminine woman, but still felt as if it was to be more liked by males. Right now I’m in a place where I don’t care. Most of the time I don’t wear makeup, I wore heels maybe twice and, despite loving being hyper feminine I know that because of men this can be harmful to a lot of women. I was weirded out by this convo because I remember having cried bc I didn’t look feminine enough. Because people would comment on my body hair or anything more masculine. I loved knowing I was better than guys by the amount of body hair as a kid but as time passed, they did everything to make me hate my leg hair. I have always thought that because of my more muscular build and face structure (sharper) males wouldn’t like me. Sometimes I still struggle in viewing myself worth as a woman in the dating experience for not fitting into beauty standards. It didn’t take me long to realise that the reason no boy liked me was that. Is a woman just femininity? Men like femininity not women. This comment as others about femboys remind me how men do not like women but just the performance of something that is meant to show softness and weakness. I like being what can be attributed to femininity but I am not a woman because of it. I am not worth as much as I can perform their fantasy. Being a woman isn’t about femininity. Being a woman is about being born with different sexual characteristics than men and being punished for it, jail since the womb.

0 notes

Text

“...Today, most – though by no means all – free countries (along with a number of rather unfree ones) have shifted from mass conscription based militaries to professional, all-volunteer militaries. The United States, of course, made that shift in 1973 (along lines proposed by the 1969 Gates Commission). The shift to a professional military has always been understood to have involved risks – the classic(al) example of those risks being the Roman one: the creation of a semi-professional Roman army misaligned the interests of the volunteer soldiers with the voting citizens, resulting in the end (though a complicated process) in the collapse of the Republic and the formation of the Empire in what might well be termed a shift to ‘military rule’ as the chief commander of the republic (first Julius Caesar, then Octavian) seized power from the apparatus of civilian government (the senate and citizen assemblies).

It is in that context that ‘warrior’ – despite its recent, frustrating use by the United States Army – is an unfortunate way for soldiers (regardless of branch or country) to think of themselves. Encouraging soldiers to see themselves as ‘warriors’ means encouraging them to see their role as combatants as the foundational core of their identity. A Mongol warrior was a warrior because as an adult male Mongol, being a warrior was central to his gender-identity and place in society (the Mongols being a society, as common with Steppe nomads, where all adult males were warriors); such a Mongol remained a warrior for his whole adult life.

Likewise, a medieval knight – who I’d class as a warrior (remember, the distinction is on identity more than unit fighting) – had warrior as a core part of their identity. It is striking that, apart from taking religious orders to become a monk (and thus shift to an equally totalizing vocation), knights – especially as we progress through the High Middle Ages as the knighthood becomes a more rigid and recognized institution – do not generally seem to retire. They do not lay down their arms and become civilians (and just one look at the attitude of knightly writers towards civilians quickly answers the question as to why). Being a warrior was the foundation of their identity and so could not be disposed of. We could do the same exercise with any number of ‘warrior classes’ within various societies. Those individuals were, in effect born warriors and they would die warriors. In societies with meaningful degrees of labor specialization, to be a warrior was to be, permanently, a class apart.

Creating such a class apart (especially one with lots of weapons) presents a tremendous danger to civilian government and consequently to a free society (though it is also a danger to civilian government in an unfree society). As the interests of this ‘warrior class’ diverge from the interests of the rest of society, even with the best of intentions the tendency is going to be for the warriors to seek to preserve their interests and status with the tools they have, which is to say all of the weapons (what in technical terms we’d call a ‘failure of civil-military relations,’ civ-mil being the term for the relationship between civil society and its military).

The end result of that process is generally the replacement of civilian self-government with ‘warrior rule.’ In pre-modern societies, such ‘warrior rule’ took the form of governments composed of military aristocrats (often with the chiefest military aristocrat, the king, at the pinnacle of the system); the modern variant, rule by officer corps (often with a general as the king-in-all-but-name) is of course quite common. Because of that concern, it is generally well understood that keeping the cultural gap between the civilian and military worlds as small as possible is important to a free society.

Instead, what a modern free society wants are effectively civilians, who put on the soldier’s uniform for a few years, acquire the soldier’s skills and arts, and then when their time is done take that uniform off and rejoin civil society as seamlessly as possible (the phrase ‘citizen-soldier’ is often used represent this ideal). It is clear that, at least for the United States, the current realization of this is less than ideal. The endless pressure to ‘re-up‘ (or for folks to be stop-lossed) hardly help.

But encouraging soldiers (or people in everyday civilian life; we’ll come back to that in the last post in this series) to identify as warriors – individual, self-motivated combatants whose entire identity is bound up in the practice of war – does real harm to the actual goal of keeping the cultural divide between soldiers and civilians as small as possible. Observers both within the military and without have been shouting the alarm on this point for some time now, but the heroic allure of the warrior remains strong.

...But as I noted above, we’ve discussed on this blog already a lot of different military social structures (mounted aristocrats in France and Arabia, the theme and fyrd systems, the Spartans themselves, and so on). And they are very different and produce armies – because societies cannot help but replicate their own peacetime social order on the battlefield – that are organized differently, value different things and as a consequence fight differently. But focusing on (fictitious) ‘universal warriors’ also obscures another complex set of relationships to war and warfare: all of the civilians.

When we talk about the impact of war on civilians, the mind quite naturally turns to the civilian victims of war – sacked cities, enslaved captives, murdered non-combatants – and of course their experience is part of war too. But even in a war somehow fought entirely in an empty field between two communities (which, to be clear, no actual war even slightly resembles this ‘Platonic’ ideal war; there is a tendency to romanticize certain periods of military history, particularly European military history, this way, but it wasn’t so), it would still shape the lives of all of the non-combatants in that society (this is the key insight of the ‘war and society’ school of military history).

To take just my own specialty, warfare in the Middle Roman Republic wasn’t simply a matter for the soldiery, even when the wars were fought outside of Italy (which they weren’t always kept outside!). The demand for conscripts to fill the legions bent and molded Roman family patterns, influencing marriage and child-bearing patterns for both men and women. With so many of the males of society processed through the military, the values of the army became the values of society not only for the men but also for women as well. Women in these societies did not consider themselves uninterested bystanders in these conflicts: by and large they had a side and were on that side, supporting the war effort by whatever means.

And even in late-third and early-second century (BC) Rome, with its absolutely vast military deployments, the majority of men (and all of the women) were still on the ‘homefront’ at any given time, farming the food, paying the taxes, making the armor and weapons and generally doing the tasks that allowed the war machine to function, often in situations of considerable hardship. And in the end – though the exact mechanisms remain the subject of debate – it is clear that the results of Rome’s victory induced significant economic instability, which was also a part of the experience of war.

In short, warriors were not the only people who mattered in war. The wartime social role of a warrior was not only different from that of a soldier, it was different than that of the working peasant forced to pay heavy taxes, or to provide Corvée labor to the army. It was different from the woman whose husband went off to war, or whose son did, or who had to keep up her farm and pay the taxes while they did so. It was different for the aristocrat than for the peasant, for the artisan than for the farmer. Different for the child than for the adult.

And yet for a complex society (one with significant specialization of labor) to wage war efficiently, all of these roles were necessary. To focus on only the warrior (or the soldier) as the sole interesting relationship in warfare is to erase the indispensable contributions made by all of these folks, without which the combatant could not combat.

It would be worse yet, of course, to suggest that the role of the warrior is somehow morally superior to these other roles (something Pressfield does explicitly, I might add, comparing ‘decadent’ modern society to supposedly superior ‘warrior societies’ in his opening videos). To do so with reference to our modern professional militaries is to invite disastrous civil-military failure. To suggest, more deeply, that everyone ought to be in some sense a ‘warrior’ in their own occupation sounds better, but – as we’ll see in the last essay of this series – leads to equally dark places.

A modern, free society has no need for warriors; the warrior is almost wholly inimical to a free society if that society has a significant degree of labor specialization (and thus full-time civilian specialists). It needs citizens, some of whom must be, at any time, soldiers but who must never stop being citizens both when in uniform and afterwards.”

- Bret Devereaux, “The Universal Warrior, Part I: Soldiers, Warriors, and…”

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Transsexing is an act of healing”

again I know Hayward has delimited a scope for this (above) --

but it seems insufficient. and i don’t know how exactly we’d differentiate transgressive potentiality from regenerative animation

dysphoria / euphoria — not sure how this maps on — not all transgressive potentialities are euphoric, not every response to dysphoria is regenerative …

and dysphoria is not always localized in/on the body — obviously that’s the intensity we’re trained to see : looking in the mirror, at the jawline, which can be cut, but also the shoulders, the feet, the hands, the entire build of the body — in the latter case dysphoria is a response to what seems immutable — not ever available for healing or regeneration — a structural impossibility —

and, to speak autobiographically, i’d say too that dysphoria can act more like an absent or retroactive cause than a symptom properly speaking — as in, healing (an “act”?) might have to take place before the symptom can make it to the surface — not always as articulate as “being in the wrong body” — sometimes too it’s just “wrong” — a sense of wrongness — and sometimes even that can’t be felt as such except in retrospect —

especially if dysphoria is dissociative — it seems like that may be a more common symptom but it’s one that can only be apprehended as such when you’re not enveloped in it — not feeling real only comes out as the problem when you come to and your reality starts to lay its film out (on the eye, in the nose) — layers sift out — where before everything was muted, behind glass, etc. — dissociation is like that -- it’s less like regeneration and more like coming up for air —

i think that’s actually what Hayward means by regeneration though: regeneration of the senses — via the flesh, “meat” (???) — why meat? — dead meat, meat market, white meat (an alternative to “flesh,” which seems more specific to racialized embodiment, at least in critical discourse -- “meat” has a feminist political resonance -- men treat us like meat, therefore we’re this kind of subject: visceral corruption, fakeness and hence disposability, subject to avid devoration and just as vicious disgust-- a ripped apart, flayed, delinked, tender (smooth) or tough (muscular) object of consumption -- also the animal studies angle obviously: “trans women” the other other white meat -- in short: meat is feminizing where flesh is racializing -- trans women is in quotes bc both Jules and Torrey point out the false presumption in that term that white trans women and trans women of color necessarily share a coherent set of experiences, much less a coalescent political subjectivity) — marked out by transition —

anyway though: if dysphoria is dissociative (disabling but not in a way that’s apparent to anyone else and maybe not to yourself either: they/you just think you’re shy, or you’re overcompensating, or you’re abrasive — whatever your particular disorder/cope is) then the response to it is not quite regenerative bc regeneration presumes something cut off and i guess in dissociation you are cut off from some kind of relationality, some kind of reality — yet it doesn’t seem cut off until you’re healing (so to speak) —

i guess i just mean to appreciate Hayward’s emphasis on a kind of regeneration without wholeness (originary or teleological) — and at the same time wonder if transsexing, as a revelation of dysphoria, (maybe through euphoria: maybe just through changed conditions), puts wholeness more radically in question — bc not only can it operate without any presumption of ideal wholeness (as origin or destination) — a suspension — but it may also depart from or involute the timeline that connects origin / destination — insofar as the symptom comes out after its regeneration

i am also thinking here about Arielle Scarcella (a lesbian youtube terf / trump endorser) and how she thinks that young trans ppl trick themselves into being trans and then get dysphoria from the transition process — obviously her political aim is retrograde but dysphoria is complex -- it may not seem to exist before an alternative is lived

again i have to insist: dysphoria isn’t actually an individual symptom anyway — it’s a response to interpellation, to an unbearable form of subject formation, a refusal or inability to respond to the incitements to inhabit your assigned sex —

assignment is not anatomical but normative — a developmental projection only loosely tethered to the genital trait it claims anchorage in — only loosely in part bc the genital only rly becomes a sex organ later, after genitalization or at puberty (pick your poison)

so there is an impasse or insufficiency in modeling the individual trans body onto the individual starfish body — and to say that “regeneration” is about healing that body — this is more fully addressed in the spider article but it’s important to stress that regeneration is kind of impossible without some kind of “building-out” (as Hayward puts it) — an architectural support — a relational field — and regeneration also means exposing yourself to further damage — not just “redressing harm” but accepting (or not accepting — just putting up with, living with) a certain level of vulnerability to harm in order to move out of the unbearable —

dysphoria isn’t an individual condition and it’s also not as acute as the “cut” in the song — it may also be accretive, built up — it may be a chronic condition, or an episodic susceptibility — dissociative episodes — recurrent

as for euphoria: a diff question — futural — infinitizing — also self-evaporating — rather than reparative — euphoria associated with falseness — false pleasure, false elation, false looking forward to an increasingly abundant future — false anticipation of the endlessness of growth — a speculative mood — yet weirdly too it can be what allows you to feel your happiness at all — as in: euphoria is “wellbeing” but that’s background unless something picks it up and makes it overwhelming — sometimes you’re happy and you don’t know it — and euphoria takes you by surprise when it comes into relief — the relief of how much better it feels — an art of living that’s not just bearable but feels perfectible and extensive — (delusive or nonendless as that feeling may turn out to have been)

i suppose you could say euphoria and dysphoria exist in some kind of dialectical relationship — i don’t think that’s the logic, because they’re more intermittent (not a spiraling momentum, necessarily) — but you could say that the infinitizing tendency of euphoria confronts dysphoria not just as a corporeal (anatomical) limit but also as an external screen — that is to say, the screen of others’ perceptions — as that which defines corporeal limits —

again whiteness is crucial: as transparency, individuating possibility of infinite self-extension — all trans bodies are subject to some degree of overdetermination from without (the dysphoric overdetermination of cis criteria) — but obvs race changes how the body is sexed — so too how it’s transsexed, transspeciated

last point: transspeciation for Hayward is a condition of biochemical transfer -- Premarin, an estrogen taken from horse urine -- what this opens up for question though is the synthetic -- what kind of transfer is that? esp. when it’s supposed to be bioidentical?

0 notes