#posledniy-geroi

Text

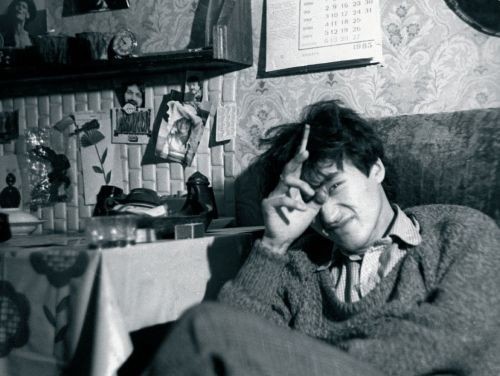

Same, Vitya. Same.

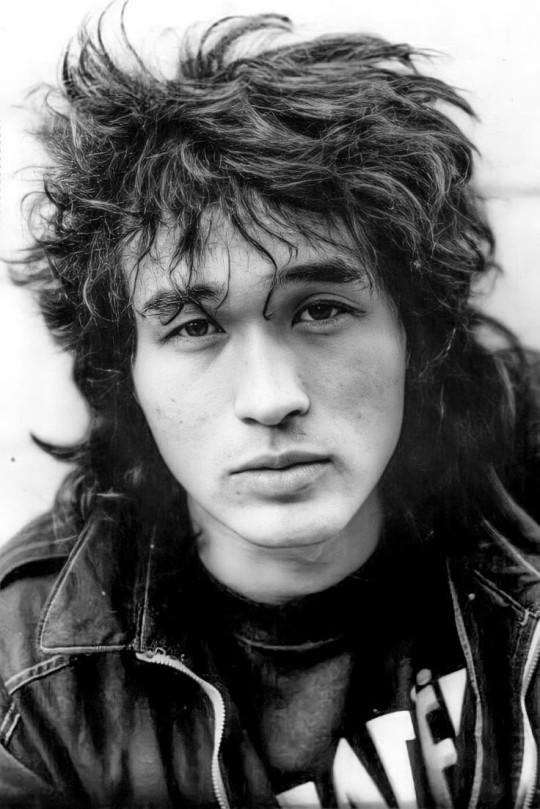

#kino#viktor tsoi#кино#виктор цой#tsoi#цой#russian rock#русский рок#rock#рок#punk#панк#последний герой#posledniy-geroi

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

KNHO Album Ranking

nocneAHNN repoN

rpynna KpoBN

3Be3Aa no NMeHN ConH4e

ETo He ni-o6oBb

4ëpHbIn anb6oM

Ho4b

45

0 notes

Text

I was tagged by @togetherasone ! Thank you!

RULES: When you get this you have to put 5 songs you actually listen to, then tag 10 people!

Griftwood - Ghost

Встречная (Vstrechnaya) - Peremotka

Последний Герой (Posledniy Geroy) - Kino

Rum e Polvere de Sparo - Banda Bassotti

Manifiesto - Víctor Jara

I'm tagging: @belissmatopolina @biximagyins @creamo-for-primo @pregnantsecondo @rightintheghoulies @postpunkk @hoeforallthepapas @gayafsatan @lyla-cc @viccy92 (you can absolutely ignore this, don't feel pressured to do it, and if you don't like to be tagged in these, just let me know!)

37 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Magnitizdat: Soviet Aligned Pop and New Wave

Mix seven of seven. The previous mixes can be found here. The YouTube playlist for this mix can be found here. Below this paragraph is the tracklisting for this mix; below that are my notes on it. It’s been a gas.

Bravo, “Koshki”

Klaus Mitffoch, “Jezu jak się cieszę”

Spenót, “Szamba”

Tango, “Na šikmé ploše”

Forum, “Davayte sozvonimsya”

Urszula, “Wielki odlot”

Pankow, “Rock ‘n’ Roll im Stadtpark”

Florian din Transilvania, “Mă simt minunat”

Trick, “Elektronnoto kuche”

Dzeltenie Pastnieki, “Sliekutēva vaļasprieks”

Marika Gombitová, “Prekážky dní”

Grazhdanskaya Oborona, “Zoopark”

Gigi, “Divat a fontos”

Maanam, “Lucciola”

Silly, “Die Gräfin”

Kino, “Posledniy geroy”

Sfinx, “An după an”

Első Emelet, “Amerika”

Aya RL, “Skóra”

OK Band, “Žižkovská zeď”

Nastya, “Tatsu”

Magnitizdat: soviet aligned pop and new wave

In a just world, just about every nation represented here would get its own mix: Poland, Hungary, Czechia, and Russia, to name just the largest pop scenes, were (and are) too capacious to be summed up in the paltry handful of songs I’ve allotted them. But I’m already teetering on the furthest outside edge of my understanding. My grasp of Europe is comparable to Saul Steinberg’s legendary view from 9th Avenue: the further East of the Pyrenees I get the more featureless and notional everything is.

To make things more complicated, although the seven nations (at the time; now 13½) represented in this mix were formally Soviet-aligned in terms of foreign policy and general economic structure, they all pursued different approaches to cultural policy, and those policies changed radically over the decades, and even from year to year. At the beginning of the 1980s, the Soviet Union was perhaps the most officially censorious in terms of rejecting Western influence, whereas places like Poland, Hungary, East Germany, and Czechoslovakia were relatively open to current trends in Western European culture, especially following the Prague Spring of 1968. Then too, one of the necessary preconditions for good pop is money (which doesn’t necessarily mean pure capitalism: state-funded arts education and broadcast media, e.g., made British pop the envy of the world), and many of the Eastern Bloc nations, whether or not they were eager to support international-style pop, were among the poorest in Europe.

Still, life finds a way. Electronic music in particular was taken up enthusiastically by many Warsaw Pact composers in the 1970s, both as a technical challenge and as a path forward into a Communist musical future that owed nothing to the dead traditions of the West. Young musicians in Warsaw, Riga, and Leningrad got hold of contraband records or reel-to-reel tapes (called magnitizdat in Russian, in parallel with printed samizdat, according to Wikipedia) of new and innovative forms of rock and pop, imitated them, and added their own perspectives. And Eastern European nations held their own national and international versions of Eurovision, and broadcast local singers in a variety of traditions, both as light entertainment and as a way to reinforce cultural nationalism.

So although Eastern Bloc pop in the 1980s was often cheaper and perhaps chintzier (or at least dedicated to different notions of cool) than its Western counterparts, there was still plenty of it; but it was also unevenly distributed. My division below is less about population size or global importance (either today or historically) than about what would fit into a single mix. There are six Soviet songs (five Russian, one Latvian), four Polish, three Hungarian, two East German, two Czech, one Slovak, two Romanian, and one Bulgarian. Linguistically, it’s my most diverse mix by far, with six Slavic languages, one Germanic, one Uralic, and one Romance language represented (the runner-up, Melodier, had five Germanic languages and one Uralic). Google Translate is my everything.

All of them are great songs, and most of them are great records as well (we’ll get to the exception), although I doubt anyone actually living in Eastern Europe, either at the time or presently, would group together these precise performers in this way: some were defiantly underground, some boringly mainstream, and most somewhere in the middle.

Most of these mixes have taken 1981 and 1987 as the boundary years: while this one ends with a longish 1987 track as per tradition, the rest of the songs are mostly clustered between 1983 and 1985. Due to protectionist policies (both Eastern and Western), inefficiencies of resource allocation, and the slow-to-arrive effects of glasnost, the new wave (if that’s even a useful term to describe a shift towards 1980s-era modernity in the diverse Communist scenes) rolled over Eastern Europe several years after it had blanketed the West. My early investigations all centered on 1984, and further research still marks that as a pivotal year.

Anyway, here’s what I’ve fallen in love with. I hope you dig it too.

1. Bravo Koshki

no label | Moscow, 1985

WIth all apologies to Long Island’s Stray Cats, Southern California’s Blasters, England’s Shakin’ Stevens, West Germany’s Ace Cats, and Barcelona’s Loquillo, the greatest rockabilly revival act of the 1980s was the Russian Браво (Bravo). Formed in 1983 by guitarist Evgeny Havtan, with singer Zhanna Aguzarova signing on later that year, they played 1950s rock and roll with a side order of 1960s ska, with lyrics simple and catchy enough to be universal but subversive enough to get them into trouble. “Кошки” (Cats) could be a children’s song: “Cats don’t look like people, cats are cats,” is the opening lyric. But when Aguzarova adds that cats don’t talk nonsense or care about bits of paper, that’s questionable, and when she launches into some of the most thrilling scatting ever heard in rock & roll it’s downright revolutionary. After the band had self-released their first recordings on magnetic tape, she was arrested for using forged identity papers in 1984, and didn’t release a proper record until 1987. She left the band in 1989 for a solo career, and is beloved throughout Russia as a sort of Lady Gaga avant la lettre, while Bravo under Havtan and a succession of singers has continued to plow their rockabilly furrow to slightly diminished success.

2. Klaus Mitffoch Jezu jak się cieszę

Tonpress | Wrocław, 1983

One of the most important Polish new wave bands, Klaus Mitffoch combined punk energy, two-tone nimbleness, and post-punk solemnity in a compulsively listenable and sometimes danceable mix. Their first single, Jezu jak się cieszę (Jesus, I’m Happy; the name is an interjection rather than an address) is a mordant portrait of callow youth that doesn’t think past the next payday, fight, or fuck, and of the system that keeps them that way: the shouty chorus translates as “Get up and be busy and own things/I can’t really do it/I don’t really want to.” A Polish “I prefer not to,” it’s a critique of the capitalist contract which worked just as well as a critique of Communist expectations: the lack of real difference between the oppressiveness of East and West will be an ongoing theme.

3. Spenót Szamba

Start | Budapest, 1983

Although I’ve been attaching the tag “new wave” to these mixes, one of the signature sounds of the US new wave has been entirely unrepresented: the beachy kitsch of the B-52’s. Until now. Spenót (Spinach) was a Budapest arts collective founded in the early 80s which only released one single on the rock imprint of the Hungarian state label: “Szamba” (Samba) b/w “Hová tűntek a szőke nőket” (Where Did the Blondes Go). Casio, bass, guitar, and disaffected vocals from Kriszta Berzsenyi (now a costumer in the Hungarian film industry) make for a minimal-funk tribute to proletarian hero Popeye, as the refrain “Everything’s perfectly fine, I’ve got spinach flowing in my veins” makes clear. A late entrance from a mariachi trumpet only adds to the delightful kitsch effect, and makes me grin ear to ear every time I listen.

4. Tango Na šikmé ploše

Supraphon | Prague, 1984

Although the island-borrowed rhythms and frontman Miroslav Imrich’s vocal qualities in this early song are rather heavily reminiscent of the Police, in terms of cultural positioning Tango were rather closer to Madness: a ska-pop band that could be goofy or heartfelt depending on the song, and burrowed deep into Czech working-class cultural identity, in part thanks to their inventive and prolific videos. Their first single, “Na šikmé ploše” (On the Slope) is a heartfelt and rather poetic love song on skis. Even after Tango’s dissolution, Imrich has been a consistently popular singer and songwriter in the years since, his work, both solo and in collaboration, ranging from ballads to techno.

5. Forum Davayte sozvonimsya

no label | Moscow, 1984

A Russian synthpop band who owed nothing to such English decadents as Human League or Depeche Mode, Форум was fronted by singer Viktor Saltykov, who had previously sung with rock band Manufactura, and anchored by synth wizard Alexander Morozov. The video for Давайте созвонимся (Let’s Call Each Other), from an early television appearance, has become a minor internet classic of kitschy Soviet aesthetics, but a google of the lyrics reveals as thoughtful and sensitive a song about love under modern technological conditions as anything Gary Numan or Scritti Politti ever recorded. Forum’s debut album wouldn’t see official release until 1987, by which time a lot of Russian pop had caught up to them.

6. Urszula Wielki odlot

Polton | Lublin, 1984

Perhaps Poland’s most prominent female rock star for the last forty years, Urszula Kasprzak has recorded in a variety of styles, from hard rock to dance-pop; but her 1984 album Malinowy król (Raspberry King), recorded with members of prog band Budka Suflera, is a minor masterpiece of cool, reflective synthpop. “Wielki odlot” (The Great Departure) was the leadoff track and the album’s lowest-charting single, but I love its stately swell and the apocalyptic lyrics (or maybe it’s just about emigration, which is another form of apocalypse). I’m looking forward into digging around into the rest of Urszula’s discography.

7. Pankow Rock ’n’ Roll im Stadtpark

AMIGA | Berlin, 1983

East Germany probably had the most thoroughly Westernized and extensive pop scene in the whole Eastern Bloc — only natural, given its proximity and exposure to West German media. But child star Nina Hagen had to leave East Berlin to help found the Neue Deutsche Welle: East Germany preferred shaggy 70s rock even as icy synths overran the NATO countries. Pankow, formed in the eponymous suburb of East Berlin, was a case in point: definitely a new wave band, they still clearly adored old-fashioned boogie rock. “Rock ’n’ Roll im Stadtpark” (Rock ’n’ Roll in the City Park) is an anthem of Communist rock (even the shouted refrains are collectivized): dancing to rock & roll in the park is better than bourgeois disco or high-priced cinema, because it’s free. Of the people, by the people, for the people, oh yeah.

8. Florian din Transilvania Mă simt minunat

Electrecord | Bucharest, 1986

The hermetic and impoverished Romanian scene, tightly controlled by Nicolae Ceaușescu’s Maoist-modeled authoritarian government, was the slowest of the European Communist nations to catch up to the present of the 1980s: officially supported music tended to be folkloric, balladic, and at its most up-to-date, hippie-era hard rock. Mircea Florian was one of the grand exceptions: beginning as a mid-60s folk-rocker in the mold of Dylan and Cohen, and maintaining a parallel interest in electronics and modern composers like Stockhausen and Nono, he moved through many progressive, electric, and Eastern-influenced musical phases over the next twenty years, often butting heads with the regime. His last great record, 1986’s Tainicul vîrtej (The Secret Swirl), released just before his defection to West Germany, was a summation of his folk- and art-rock past and his new-wave present. This opening track “I Feel Great,” is a statement of gleeful modernism, the lyrics an expression of bucolic alienation while the synthesizers and drum machines wander off on prog-rock solos before being recalled to robot rhythms.

9. Trick Elektronnoto kuche

Balkanton | Sofia, 1985

If the Romanian rock scene was impoverished, its Bulgarian counterpart was even more so. Trick was a vocal group — two women, one man — put together out of music school in frank imitation of Western acts like ABBA, Boney M, or even (if the record sleeves are any indication) Tony Orlando and Dawn. But this cut from their first LP, “Electronic Dog,” was produced by the young, ambitious Kristian Boyadzhiev to a hypermodern sheen: if the girls are still essentially singing disco harmonies, at least the music has heard of ZTT. After release, the song was suppressed by Bulgarian state media on the grounds that the goofy lyrics and synthesized dog barks were making a mockery of Bulgarian electronics. But today, it sounds like it might predict Eastern European trance.

10. Dzeltenie Pastnieki Sliekutēva vaļasprieks

no label | Riga, 1984

The underground new-wave scene in Latvia was apparently the most active and prolific in the Soviet Union outside Mother Russia: the Baltic seaport of Riga, as one of the USSR’s few access points to global culture, saw bands like Pērkons, NSRD, and Dzeltenie Pastnieki making waves even as their magnetic-tape recordings were suppressed by the Soviet authorities and not released for decades. I chose this song by Dzeltenie Pastnieki (Yellow Postmen) not because it’s exceptionally better than the rest of their material, which is all pretty great, but because its combination of electronic loops and sensitive guitar sounded surprisingly to me like the Postal Service. The pitch-shifted vocals, sure, sound more like “The Laughing Gnome,” but that’s no deal-breaker.

11. Marika Gombitová Prekážky dní

Opus | Bratislava, 1984

Probably the biggest Slovak pop star of the era, Marika Gombitová had been well-known in the eastern half of Czechoslovakia since 1977, when she sang leads for the popular rock band Modus. This synthpop gem (Daily Obstacles) from her fifth album, the unselfconsciously-titled No. 5 (it was her first stab at singing to synthesizers), uses sporting metaphors to talk about desires that slip forever out of reach, the evocativeness of which imagery would not have been lost on a contemporary television-watching audience: Gombitová had been confined to a wheelchair, paralyzed from the shoulders down, following a car crash in 1981. Her marvelous voice, thin but strong, reminds me of Cyndi Lauper’s: and the gorgeous production, with its slippery bass and a haunting electronic solo in the middle eight, makes this maybe my favorite song in this mix.

12. Grazhdanskaya Oborona Zoopark

no label | Omsk, 1985

Here’s that not-great record, meaning only that it’s extremely lo-fi, so much so that the tape hiss and room tone plays practically an aesthetic role, turning a simple rock ballad into a fuzz-pop gem that could sit side-by-side with contemporary work by the Beat Happening or Hüsker Dü. Гражданская Оборона (Civil Defense) was the psych-rock project of Siberian-born Yegor Letov; after their first magnetic tape, containing “зоопарк,” was recorded, band members were institutionalized, their subversive attitudes having been dutifully reported to the authorities by the guitarist's mother. That subversiveness isn’t hard to detect in this song, in which Letov dreams of finding other crazy people (like him) with whom he can plot an escape from the zoo of contemporary life.

13. Gigi Divat a fontos

Start | Budapest, 1985

Nobody on the Internet seems to know anything about Gigi, not even whether the name is of a performer or a group. The writing credit on the Hungarian compilation LP where “Divat a fontos” (Fashion Matters) appeared is to “Gigi Együttes,” which latter word just means Ensemble. But a bunch of people on the Internet, some in Hungarian, some in English, and some in Polish, have warmly praised this song, an aerobic synthpop jam that combines the best of Kim Wilde and Olivia Newton-John. It’s apparently all that this Gigi (the thirty-first entity of that name on Discogs) ever recorded, but it’s enough.

14. Maanam Lucciola

Polskie Nagrania Muza | Kraków, 1984

The post-punk band Maanam, on the other hand, are legends of Polish rock, with dozens of records and a rabid fanbase: one of the most successful and important Eastern European bands of the decade. Lead singer Kora (Olga Jackowska)’s vocal style owed little to Anglophone precedent, digging deep into Slavic and Polish modernism, even when, as here, the most frequent word in the song is the Italian woman’s name of the title. In “Lucciola,” Kora dispassionately portrays a man searching for the titular woman in the night wind, while the band’s brawny Gang of Four funk motorvates right along regardless.

15. Silly Die Gräfin

AMIGA | Berlin, 1982

Probably the most interesting East German rock band of the 1980s, Silly was centered around the vocal performances of Tamara Danz, who could be kabarett-outrageous in one song and luminously synthpop-tender in the next. “Die Gräfin” (lit. The Countess, but also slang for any stuck-up woman) is a funk-rock vehicle for her gift for satirical vocal caricature, as she mocks the decayed German aristocracy from a victorious proletarian point of view. Not that Danz was a strict ideologue: in 1989, she joined other East German musicians in demanding greater freedom, in protests that helped lead to the collapse of the Communist consensus. She died in 1996 of breast cancer, far too young.

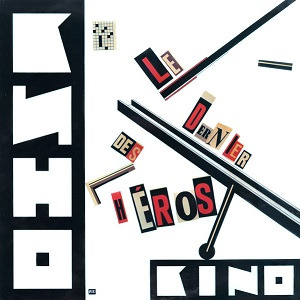

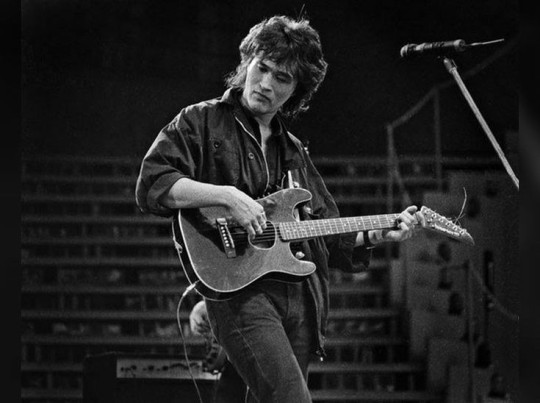

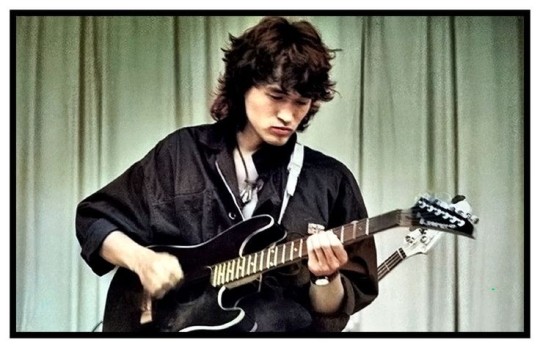

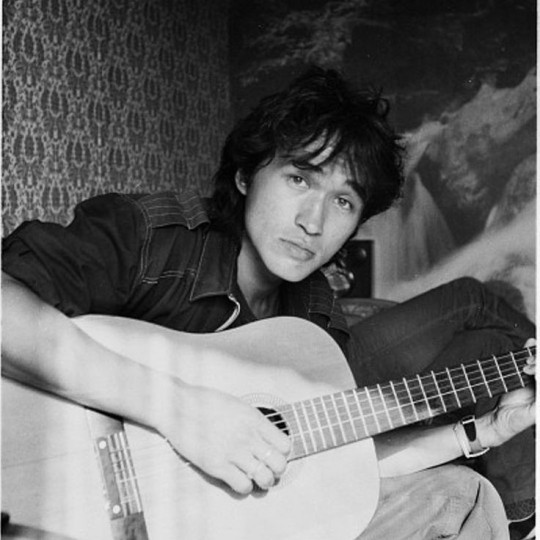

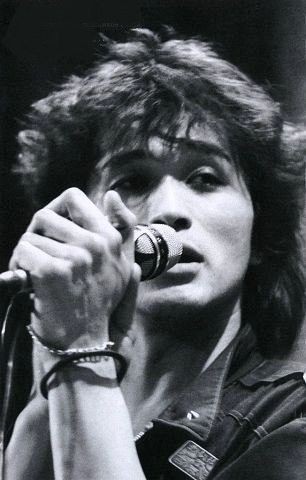

16. Kino Posledniy geroy

AnTrop | Leningrad, 1984

The only Russian band represented on this mix whose music was officially released within the era under consideration, Кино (Cinema) were no less skeptical about the Soviet system than their peers, just luckier in that they hooked up with the independent Leningrad-based AnTrop label, which gave them cover for sarcastic, despairing songs like Последний герой (Last of the Heroes), in which the familiar 80s theme of nuclear annihilation gets another airing, and East and West turn out to be not so different after all.

17. Sfinx An după an

Electrecord | Bucharest, 1984

When Mircea Florian was one of the leading lights of Romanian prog in the 1970s, one of his few competitors in the field was the band Sfinx (Sphinx), formed in the mid-60s to play Western-style pop/rock. In the following decade, they grew more ambitious, taking cues from Yes, King Crimson, and Genesis, the last of whom, in their 80s incarnation, is a reference point here. “An după an” means Year After Year, and even though it was only their second LP (they were constantly running afoul of the Romanian censors), it was occasion for a wistful look back over the last twenty years.

18. Első Emelet Amerika

Start | Budapest, 1983

Perhaps the most popular Hungarian rock band of the early 80s, Első Emelet (First Floor) was formed from the remnants of several less fortunate acts which imploded around 1982. With a bright, energetic sound, witty lyrics by songwriter Péter Geszti, and an irreverent comic sensibility to their visual presentation, they were just the kind of band that would have been a lock to appear on MTV if they weren’t from a Communist nation. In fact, they did anyway — one of the television screens in Dire Straits’ “Money for Nothing” is playing an Első Emelet video. Their first single, “Amerika” is a terrific satire of that consumerist paradise, rendered with all the plastic pomp the subject deserve.

19. Aya RL Skóra

Tonpress | Warsaw, 1984

One of the greatest long-running European indie-rock bands, Aya RL (for Red Love) formed when Russian keyboardist Igor Czerniawski and Polish singer Paweł Kukiz met in Warsaw. “Skóra” (Skin), their biggest hit and most well-loved song (I dare you to get that wordless chorus out of your head), is somewhat unrepresentative of their more psychedelic and intellectual work — but it’s a great song, a portrait of love despite the turmoil and violence of the heavily politicized street culture of Warsaw in the 1980s.

20. OK Band Žižkovská zeď

Supraphon | Prague, 1982

If you didn’t know anything about Eastern Bloc music in the 1980s and relied only on what the Western media of the time showed you, you might expect it all to sound like this: icy, measured, foreboding. In fact, “Žižkovská zeď” (The Zizkov Wall) is just about the slowest and coldest song in Czech synthpop act OK Band’s repertoire: most of it is much cheerier and romantic. But I really dig its coldwave vibes and the sound of Marcela Březinová’s voice singing about the awful feeling of seeing your name written in graffiti by an unknown hand.

21. Nastya Tatsu

no label | Sverdlovsk, 1987

Thanks no doubt to my own global position — in the (allegedly) democratic West — I’ve been focused throughout this mix on how the music of Communist Europe responds to or relates to or recalls its Western counterparts. But with “Tatsu,” the gaze shifts not West, but East. Nastya, a band formed on the border of Europe and Asia, and named after its frontwoman, singer, composer and poet Anastasia Polova, was fascinated with Japanese folklore, history, and mythology. The Tatsu of the title is both a Japanese child left for dead in World War II (that’s where the bits in English come in), and a mythological dragon-god protecting islands in the Pacific. It’s an amazing song, the centerpiece of an amazing album, and the fact that it only circulated as a bootleg tape for a decade before being officially issued in the mid-90s is the strongest indictment of late-Soviet cultural policy I know. I say that as a Communist.

That’s it, that’s all the mixes. For now, anyway. Thanks for reading and listening and sharing and liking. I’ve got other projects to keep me busy; I’ll try to mention them here from time to time.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

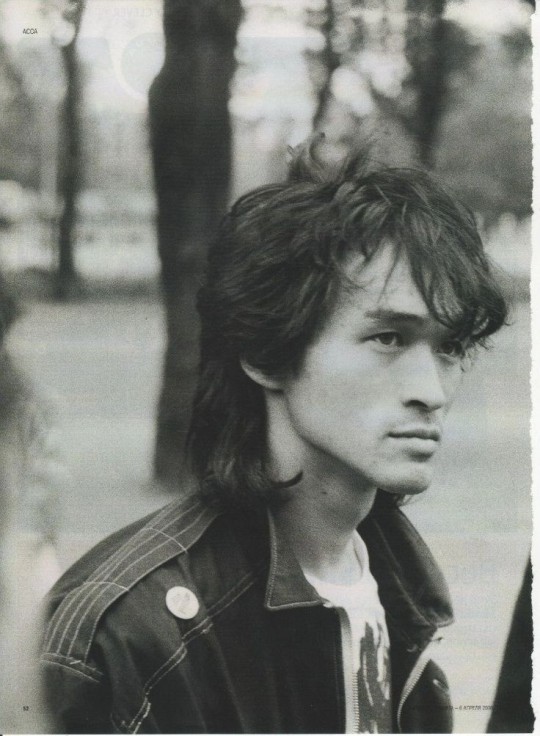

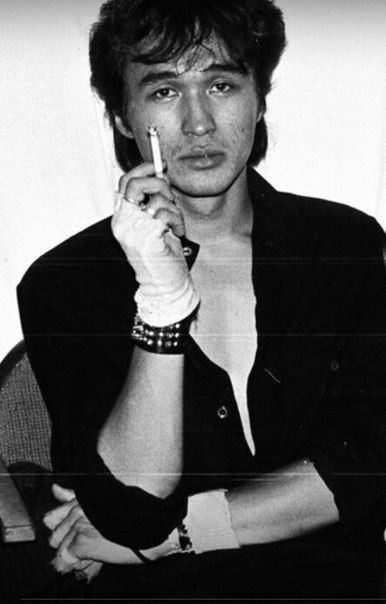

#kino#viktor tsoi#кино#виктор цой#tsoi#цой#russian rock#русский рок#rock#рок#punk#панк#последний герой#posledniy-geroi

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

#viktor tsoi#виктор цой#kino#кино#tsoi#цой#russian rock#русский рок#rock#рок#punk#панк#последний герой#posledniy-geroi

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

#kino#viktor tsoi#кино#виктор цой#tsoi#цой#russian rock#русский рок#rock#рок#punk#панк#последний герой#posledniy-geroi

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Здравствуй, последний герой.

#kino#viktor tsoi#кино#виктор цой#tsoi#цой#russian rock#русский рок#rock#рок#punk#панк#последний герой#posledniy-geroi

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

🖤🩶🖤

12 notes

·

View notes