#pannikin building

Text

Andaz Hotel and Pannikin Building Wedding Photos | J+R

Andaz Hotel and Pannikin Building Wedding Photos | J+R

Andaz Hotel and Pannikin Building Wedding Photos | J+R

As a San Diego wedding photographer, I usually find myself photographing weddings near a beach or nature. It’s nice to mix things up and get a different terrain. It’s ideal to have the wedding venue be all in one place, but sometimes there are multiple locations involved. In these Andaz Hotel and Pannikin Building Wedding Photos | J+R had 3…

View On WordPress

#California elopement photographer#California Wedding Photographer#Melissa Montoya photography#pannikin building#pannikin building san diego#pannikin building wedding#San Diego elopement photographer#San Diego engagement photographer#San Diego micro wedding photographer#San Diego photographer#San Diego wedding photographer#The Andaz hotel#the andaz hotel san diego#the andaz hotel wedding

0 notes

Text

Winthrop Avenue swung as a pendulum. Divers felt its stones, and found a thick crown of chenille stems. Bare feet walked, and skipped, on the dry stones, flipping them like coins. Towers of news overlook the scattered silhouettes of walkers far below, where we are; the sharp buildings spread into the distance above rather than narrowing, so that they are like near planets.

Tweasures, the things we are tweasuring: Nazgul giving the willies to my spotted cow and calf, for instance. Let the sprinkled birds fly to the poles, and throw seeds after their departing tails. Frog coattails dragged on the ground, and we didn’t know: the pies ate them, with their long mouths, into their dark gullets, openings into the leeching blackness of a thousand dungeons whence nothing returns but the smell of death.

The long-haired ones gathered the small rods, and drew them to choose. The letter Y was the long rod, and went to fetch a pannikin from town.

2022/10/13 #dailywrittenoom

0 notes

Text

How One Woman Changed the Coffee Industry

Note: last year, I was invited to contribute a piece on the ‘second wave’ of coffee to the Deutsches Museum’s exhibit ‘Cosmos Coffee’. The following is the text of my contribution. Many thanks to exhibit curator Sara Marquart for the invitation.

* * *

In 1968, a professional secretary named Erna Knutsen took a job in a coffee trading firm in San Francisco. Part of her job was to maintain the “position book” in which accounting records were kept concerning the company’s coffee inventory and contracts with BC Ireland, a well-established coffee importer. Although born in Norway, Knutsen had grown up in New York City, a place where––like the rest of America––coffee had become the definitive everyday drink: ubiquitous, commonplace, ordinary. Though coffee’s origins are in Africa and the Middle East, and early European and American coffee drinkers recognized the deep cultural roots and special flavor of coffee, by the mid-twentieth century American enterprise had tamed the exotic coffeehouse and sanitized the smoky, brash coffee roasting companies. Coffee had become slick big business and, by the 1950s, coffee was a quotidian drink for most Americans, a commodity sold pre-ground in cans lining the shelves of polished, sterile “supermarkets.”

By the late 1960s, coffee was in trouble. Per capita coffee consumption had fallen steadily since the end of World War II and young people were rejecting sanitized commercial coffee brands as boring, tasteless, and square. Slowly, in the latter half of the 1960s, a different vision of coffee began to emerge in cities on the West Coast of the United States. Alfred Peet, an immigrant from the Netherlands whose father used to run a coffee roasting company in Europe, had worked in America’s coffee industry and found it lacking in quality and variety. He established Peet’s Coffee, Tea, and Spice in Berkeley in 1966. His shop liberated coffee from its steel cans and sold whole beans, scooped from gleaming brass bins into simple paper bags, alongside exotic teas and spices. Decorated with wood paneling and vintage coffee equipment, Peet’s evoked a nineteenth-century coffee aesthetic and was a rejection of the space-age modernism of the 1960s supermarket.

Soon, Peet was joined by others: in 1968 in San Diego, Bob Sinclair founded Pannikin Coffee Tea and Spice, which sold freshly roasted coffee alongside handmade cookware. That same year, after honeymooning in Sweden and experiencing a coffee epiphany, Herbert Hyman opened his first coffee store in Los Angeles, called the Coffee Bean. In 1971, Jerry Baldwin, Zev Siegl, and Gordon Bowker, three friends who met at the University of San Francisco and who were inspired by Peet’s vision of coffee, founded Starbucks in the city of Seattle, naming the company after a character in Hermann Melville’s classic novel Moby Dick. In 1972, Carl Diedrich, a German immigrant who arrived in the United States via Guatemala, established his own coffee company in Costa Mesa, California. George Howell, also inspired by Peet’s in Berkeley, brought the vision to Boston, founding the Coffee Connection in 1974. Before long, most urban metropolitan areas in the United States had their own small coffee company, dedicated to a common vision of quality coffee and freshness.

From her secretary’s desk, Erna Knutsen could see something unique was happening. These new, young, quality-oriented coffee companies were asking her for “special coffees.” They insisted on the very best quality, seeking out unusual varieties, historic origins, and meticulously prepared “lots.” Realizing that her bosses at the coffee trading firm thought of these new coffee companies as an annoyance, Knutsen began to focus on identifying these special coffees and presenting them to her audience of small, quality-oriented coffee companies, building a little side business. It was in an article she wrote for the Tea and Coffee Trade Journal in 1974 that she called this new market segment “specialty coffee.” In building her business and documenting the rise of a new generation of coffee companies, Knutsen was one of the first to identify what we now call the second wave of coffee––a group of coffee entrepreneurs who, in rejecting the norms of the commodity coffee business of the mid-twentieth century, created an aesthetic and a movement of their own.

Erna Knutsen at her desk.

The specialty coffee era emerged as America rediscovered gastronomy. Led by culinary enthusiasts like Julia Child and Craig Claiborne, a new movement helped Americans discover the regional cuisines of Europe, explore the ethnic diversity of food in the United States, and partake in the excitement of exploring food traditions from around the globe. In 1968, Child’s television show The French Chef was at the peak of its popularity, introducing Americans to the techniques and traditions of French cooking. New York Times food editor Craig Claiborne’s Kitchen Primer was published in 1972, introducing his readers to French, Italian, and Spanish cooking techniques, complete with instructions on brewing fresh coffee. This aesthetic of culinary technique, gastronomic exploration, and a do-it-yourself ethos created a fertile environment for entrepreneurs with a zeal for coffee, flavor, and cuisine. It should be remembered that many of these coffee companies sold spices, cookware, and books alongside coffee. This meant that coffee became central to a lifestyle that embraced good food and drink and the desire to cook “the hard way,” and eschewed the conveniences of frozen-food dinners and pre-ground coffee.

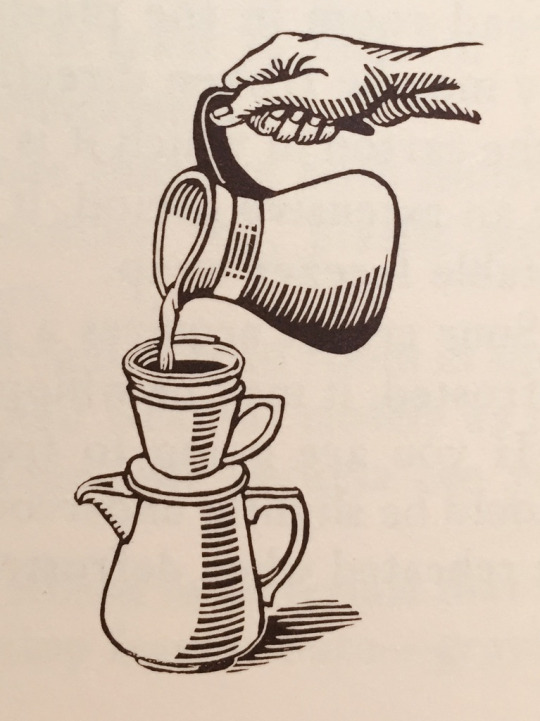

detail of coffee brewing in Craig Claiborne’s “Kitchen Primer” by illustrator Tom Funk, 1972

The second wave of coffee went hand-in-hand with a new sense of cultural exploration. The 1960s and 1970s were an era characterized by ethnic identity and pride, and specialty coffee companies incorporated cultural awareness – particularly of Latin America and the Pacific Rim––into their own identities. Royal Coffee and Knutsen herself sang the praises of Mandheling coffees from Indonesia, George Howell celebrated Huichol art, Pannikin integrated Mexican chocolate and indigenous Mesoamerican folkways into its company identity. All this exemplified these companies’ attempts to communicate and celebrate the cultures from which coffee was sourced. “Offering sheets” and newsletters from coffee importers circulated by post and by fax in the pre-internet era provided a critical education in the coffee trade to the widely-scattered companies of the second wave. Erna Knutsen’s missives, enthusing about the qualities of the coffees she traded, became legendary, as did updates from Royal Coffee and others. Second wave roasting companies from this period embraced the offering sheets aesthetic of the coffee importers and began to expose consumers to the language of the coffee trade, adding regional names like Guatemala Antigua and Ethiopia Harrar to coffee menus, alongside technical trading terms like “Kenya AA” and “Colombia Supremo.”

All of this was done in a spirit of cultural rebellion. Taking their cues from the back-to-the-land and bohemian movements of the late 1960s, second wave coffee companies embraced a style of rebelliousness and nonconformist business practices that came to typify the movement. Bob Stiller founded the Green Mountain coffee company only after the success of his first business, “E-Z Wider,” a company that manufactured rolling papers for use in smoking marijuana and was named after the seminal counterculture film Easy Rider. Paul and Joan Katzeff founded their company Thanksgiving Coffee as a “hippie business.” Although Alfred Peet embraced a conservative personal style, his shop in Berkeley became known as a countercultural hangout, and its regulars became known as “Peetniks,” after the Beatniks.

In the 1980s, these companies began to be embraced by the wider community, having already become well known to the culinary elites and bohemian subcultures of the cities they served. Individual, idiosyncratic outposts turned into local chains of retail stores, which began to host coffeehouses too. In 1982, the Specialty Coffee Association of America was founded. Erna Knutsen helped lead the way in providing a professional association that could assist with establishing standards and educating personnel at the companies participating in the movement.

In the tradition of the second wave’s celebration of European coffee style, Howard Schultz incorporated the Italian espresso bar aesthetic in his Il Giornale project, which became an integral part of Starbucks’ identity. Second wave specialty companies became known more for their beverages than their beans, and the Italian “caffè latte” simply became a “latte”, which in turn became synonymous with specialty coffee in popular culture. The espresso bars and coffeehouses of the specialty coffee companies began to typify the movement, and became essential parts of urban and suburban communities in the 1980s and 1990s. Ray Oldenburg’s 1989 book The Great Good Place specifically focused on specialty coffee shops as important elements in American cultural life, and these second wave companies began to take their role as curators of public space more seriously.

By the 1990s, the second wave of coffee was cresting. Peet’s, Starbucks, Coffee Connection, and many others were expanding rapidly, opening new stores to meet consumers’ demand for high quality coffee beverages, specialty coffee beans, and public spaces where communities could come together. But then the coffee tradition that commenced with a counterculture identity and culinary approach began to be seen as ubiquitous and standardized, and incorporating elements of the 1950s coffee culture it was established to oppose. Coffee shops began to be regular features of suburban strip malls, specialty coffee brands began to appear in pre-ground packages on supermarket shelves, and espresso bars began appearing in gas stations and airports. This led to a great conflict within the specialty coffee movement: was its rapid expansion evidence of “selling out” and abandoning specialty coffee values, or was this a mission with a higher purpose––bringing great coffee to the masses? Were the ideals expressed in Erna Knutsen’s moniker “specialty coffees” possible in the context of mass markets and public stock offerings?

A counter-movement within specialty coffee began to form. This loose group of professional craft coffee roasters established themselves as the Roasters’ Guild, objected to the commercial excesses of the second wave and sought to build a new movement that recommitted to values of quality, freshness, and artisanship. Young entrepreneurs who had worked as baristas or roasters for the second wave companies began to establish companies of their own, seeking to reclaim the mantle of specialty coffee and create new cutting edge coffee.

Some made the transition between generations––Erna Knutsen and George Howell remained relevant to the next generation of coffee entrepreneurs even into their 70s and 80s––while other specialty coffee companies sold or folded. A new generation of specialty coffee had arrived. Trish Rothgeb identified the third wave of coffee in her influential 2003 essay “Norway and Coffee”, published in the Roasters Guild newsletter. Third wavers built upon the culinary drive, cultural exploration, and spirit of rebellion that epitomized the early specialty coffee movement, and brought those values to a new generation. And Erna Knutsen, who had ushered in the original specialty coffee revolution, was there cheering it on.

In June, 2018, Erna Knutsen passed away at the age of 96. Her passing may well mark the definitive end of the second wave of coffee, but the ideals and aspirations of the specialty coffee community live on.

18 notes

·

View notes