#my main problem is not having the mirror neurons that simulate the emotions of other people in my own brain

Text

Hell yeah automatic renewal on my library book

#I'm only half way through#turns out taking detailed notes takes a damn long time#especially when you're essentially transcribing the entire book into a bullet point format#girl i need this information and the book has to go back so I'm writing the whole damn thing down#plus it helps me actually absorb the information when i have to read every sentence 2-3 times and also write it myself#learning about the neuroscience of human communication 👍#having actual mechanical knowledge of complicated concepts like my own consciousness makes it easier to troubleshoot and resolve issues#it's like “hey when you're experiencing this emotion here's what's happening and why and how you can slowly change that reaction”#i wasn't born with the intuitive understanding of emotional connection allistic people apparently have#but I've always been a powerhouse in the classroom#i have full confidence in my ability to absorb information and to learn to apply it appropriately in various situations#i have the pattern recognition to tell when someone's feeling a way with pretty good accuracy#Chinese dramas are really good for studying facial expressions and emotion because they do a lot of acting with their eyes#my main problem is not having the mirror neurons that simulate the emotions of other people in my own brain#so i have the information and i understand what it means#but i also can't help thinking it's odd to feel that way because only the data comes across and not the emotion itself#but if i get a detailed enough understanding of human behavior i think i can make up for that#and with enough applied effort over time i might be able to build those networks in my own brain on purpose#bc it's not like I'm fully missing them#when someone in a show or book is sad i do cry#but i think my defenses are up too high in person to let anything through#i have noticed increased understanding and something like empathy developing lately#still not feeling the feelings but i can recognize and accommodate them which is a lot better than i used to be

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Advanced digital networks look a lot like the human nervous system

by Salvatore Domenic Morgera

Studying digital and biological connections can shed light on both fields. MY stock/Shutterstock.com

Parents have experienced how newborns grab their finger and hold tight. This almost instantaneous response is one of the sweetest involuntary movements that babies exhibit. The newborn’s nerves sense a touch, process the information and react without having to send a signal to the brain. Though in people this ability fades very early in life, the system that enables it offers a useful example for digital networks connecting sensors, processors and machinery to translate information into action.

My research on both the human nervous system and advanced telecommunications networks has found some striking parallels between the two, including the similarity between babies’ nervous systems and the rapid-response networks now being developed to handle always-on, always-connected networks of sensors, cameras and microphones throughout people’s homes, communities and workplaces.

These insights can suggest new ways to think about designing future telecommunications systems, as well as provide new ideas for diagnosing and treating neurological disorders like multiple sclerosis, autism spectrum disorder and Alzheimer’s disease.

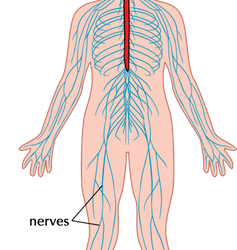

A view of human neurology

Generally speaking, the nervous system has three main components: the brain, the spinal cord and the peripheral nervous system.

The human nervous system can be understood as a network of interconnected sensors and processors. Siyavula Education/Flickr, CC BY

The peripheral nervous system is distributed throughout the entire body, sensing inputs like pressure, heat and cold, and conveying that information through the spinal cord to the brain. This system also handles the responses from the brain, controlling voluntary movements, and does some local regulation of involuntary body functions like breathing, digestion and keeping the heart beating.

The spinal cord handles large numbers of sensory inputs and action responses passing back and forth between the brain and the body. It also handles involuntary muscular movements called reflex arcs, such as the knee jerk reflex when the doctor performs an examination or the rapid “pull away” of a hand when something hot is touched.

The brain, the center of most of the nervous system’s processing power, has several specialized regions in its right and left hemispheres. These areas take input from sensors such as the eyes, ears and skin, and return outputs in the form of thoughts, emotions, memories and movement. In many cases, these outputs are also used by other parts of the brain as inputs that enable refinement and learning.

In healthy people, these elements work together in extraordinary harmony by combining networks of cells that respond to specific chemicals, mechanical changes, light characteristics, temperature changes and pain through a process called sensory transduction. This complexity makes even one of the smallest components of the nervous system, the nerve fiber, or axon, a challenge to study.

Some of the nervous system’s interconnections, long thought to only be physical, may also be effectively wireless. The brain generates a highly specialized electric field at certain nerve fiber sites during the normal course of its operation. Measuring the characteristics of this field can offer indications that a brain is healthy, or that it may have certain neurological disorders.

Inside telecommunications networks

The current generation of advanced telecommunications networks, known as 5G, is wireless, and has three similar categories of components.

The digital equivalent of the peripheral nervous system is the “internet of things.” It is a vast and growing network of devices, vehicles and home appliances that contain electronics, software and connectivity that let them connect with each other, interacting and exchanging data.

The technological equivalent of the brain is the “cloud,” an internet-connected group of powerful computers and processors that store, manage and process data. They often work together to handle complex tasks involving large amounts of input and processing, before delivering outputs back over the internet.

In between those two types of components is the spinal-cord equivalent, a new type of network called a “fog” – a play on the fact that it’s a thinly distributed cloud – set up to shorten network connections and the resulting processing delays between the cloud and remote devices. The processors and storage devices in the fog can handle tasks that require especially rapid reactions.

Striking similarities

In building technological networks throughout the modern world, people have apparently – and likely unconsciously – mirrored human neurology.

This offers opportunities to identify technological solutions to networking problems that could be adapted into medical treatments for neurological disorders that have no known cures.

Autism spectrum disorder, for example, is a serious developmental condition that impairs people’s ability to communicate and interact. It’s believed to occur as a result of an imbalance between two types of neural communications: People with autism spectrum disorder have too much activity in neurons that excite other neurons and too little activity in neurons that quiet other neurons down. This is like what happens when some links in a telecommunications networks get overloaded, while others are not busy at all. Software tools that manage large cloud and fog networks can even out demand and minimize telecommunication delays. These programs can also simulate – and suggest ways to reduce – the network imbalances in autism-related impairments.

youtube

Salvatore Domenic Morgera explains the network of the nervous system.

Multiple sclerosis is an often disabling disease in which the body’s immune system eats away at nerve fibers’ protective coverings. This disrupts the flow of information within the brain, and between the brain and the body. Technologically, this is similar to outages at particular network connection points, which is regularly dealt with by sending messages by other routes that have working connections. Perhaps medical research can identify ways to reroute nerve messages through nearby links when some nerves aren’t working properly.

Using software and medicine together

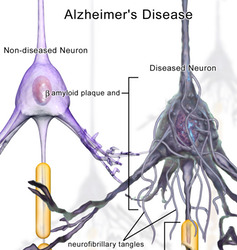

Neural communications break down when affected by Alzheimer’s disease. BruceBlaus/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

Alzheimer’s disease is a type of dementia that causes problems with memory, thinking and behavior. In 2015, I presented work by my research lab on the discovery of new networks in the brain whose behavior indicated that Alzheimer’s disease might be an autoimmune disease, like MS is. This suggests a brain with Alzheimer’s could be like a telecommunications network being attacked by an intruder changing not just data within the network, but also the network’s structure itself.

My research group then used the human immune system as inspiration for developing software to defend computer networks against malicious attacks. This software can, in turn, be used to simulate the progress of Alzheimer’s disease in a patient, perhaps highlighting ways to reduce its effects.

The nervous system’s involvement in other autoimmune diseases, such as Type 1 diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis, may offer opportunities for additional insights into digital networks, or ways sensors and software solutions might help patients. In my view, software models, made more realistic by clinical research, will help researchers understand the structure and function of the human nervous system and, along the way, make telecommunications networks and services faster and more reliable and secure.

About The Author:

Salvatore Domenic Morgera is Professor of Electrical Engineering and Bioengineering at the University of South Florida

This article is republished from our content partners at The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

#technology#science#neuroscience#Digital Networks#5G#Multiple Sclerosis#Autism Spectrum Disorder#alzheimers#Neurological conditions#neurological disorders#medicine

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

The experientiality of narrative

An enactivist approach.

Marco Caracciolo

Caracciolo starts his writing outlining experience and consciousness as privileged objects of philosophical investigation and states his objective to merge this with cognitive sciences for a theory he refers to as Enactivism. This involves an exploration into cognitive psychology, neuroscience and philosphy of the mind. He focuses on embodiment, experience and interaction to underly claims of readers engagement with narrative, advocating what he refers to as the E-approach to experientiality of narrative. The ‘E’ stands for:

-Embodied, Embedded, Enactive, Engaged and evaluative.

His goal is to provide insights into our experiential engagement with stories through themes of autonomy, sense-making, emergence, embodiment and experience. His approach enlists a merging of what he refers to as ‘non-professional’ readers and their emotional/immersive engagements with narratives and the more ‘self-conscious’ literally critical readers. In other words imagination and forms of meaning making mediated by propositional thought and socio-cultural appraisals.

Stories themselves offer themselves as imaginative experiences because of the way they draw on and restructure the readers familiarity with experience itself. What characterizes an experience is the structure which seems to straddle the divide between real and fiction. He argues that engaging with stories can be an imaginative experience to account for the difference between engaging with the world and engaging with narrative but that these are not two kinds of experiences in a strong sense.

At the core of any narrative interaction is the tension between the story and what he calls the ‘experiential background’ of the reader. This is because consciousness is not a passive taking of sensory information from the outside world but a structure of interaction between embodied subjects and the environment they negotiate. The engagement is always projected against ‘experiential background’ - a repertoire of past experiences and values that guides peoples interaction with the environment.

Fictional storytelling can break the laws of reality whether by representing physically or naturally impossible states of affairs or by challenging representational conventions and socio-cultural assumptions about the real world. While imaginative contents and experiential qualities of fiction may deviate from real world engagements, the underlying structure of interaction is the same. Readers (or recipients) respond to narrative on the basis of their experiential background.

Two psychological mechanisms play a role in this process:

-Triggering memories of past experiences or experiential traces.

-Mental simulation, which allows readers to put together past experiential traces in novel ways, therefore sustaining their first person involvement with both fictional characters and the spatial dimensions of story worlds.

Stories need experiential input but also produce some output, since they can bring about a restructuring of each readers experiential background by generating new ‘story-driven’ experiences.

The experiential background of recipients includes the socio-cultural contexts that frame their encounters with narrative. He makes a case for the involvement of bodily experiences in the interpretation addressing the larger issue of how narrative can tap into readers past experiences and provide new ‘story-driven’ experiences on the basis of their experiential background. For example we can look at how emotional reactivity can be provoked by narrative. We might cry while watching a film because we recognize the film is dealing with values that are part of our own experiential background. Narrative can leave a mark on readers at the level of their more self-conscious and culturally mediated judgement about the world.

It has been widely assumed that stories work by representing events, situations, characters and mental processes or in other words ‘ narrative is the representation of an event or a series of events (Porter Abbott). The enactivist viewpoint challenge that definition by urging that experience is not a matter of representation, but rather an interaction with the world guided by the values that permeate the subjects experiential background. A large portion of his argument is dedicated to reconciling this insight with the assumption that stories are representational devices.

This is because stories, and language, are inherently representational. Engaging with literary texts does involve representations in both the semiotic and cognitive science sense. Semiotic and mental representations play a role in the readers interaction with a story but it is not the whole picture for the experience readers get cannot be adequately reduced to mental representations. this is because experience has to do with how things are experienced, with a field of possible interactions relating to the context -evaluative and embodied- creating a sense of complexity. Mental representations in his context refer to symbolic structures that carry content by representing many different kinds of objects eg. concrete objects, sets, properties, events and states of affairs in this world, possible worlds, fictional worlds as well as abstract objects such as universal and numbers.

As both reader-response and rhetorical narrative theorists have recognized, stories have an impact on readers, provoking reactions in the form of mental imagery, emotional responses, moral and aesthetic judgement and socio-cultural evaluations. during the experience of a story these responses will often come together in interesting and surprising ways. for example we will try to show that readers bodily involvement can strengthen their engagement with a story at a level of social-cultural meaning.

The aim of cognitive approaches to literature is not to prove scientifically readers interpretative response to stories, rather it is to show that these socio-culturally nuanced responses can be placed on a continuum with more basic modes of interaction with the world. Caracciolo states a tendency to acknowledge that cognition is embodied and situated or in other worlds, inseparable from the subjects body and from the context it is situated.

Gibbs writes

“Embodiment may not provide the single foundation for all thought and language, but it is an essential part of the perceptual and cognitive process by which we make sense of our experience in the world”

The self, personal identity and how we come to understand the behaviour of others

Psychologist Jerome Bruner has helped popularize the view of Narratives being instrumental in shaping our personal identity. An important precedent to the next debate centered on the ‘problem of other minds’ which asks: what is the core mechanisms whereby we make sense of other peoples intentional behavior?

traditionally this debate has been dominated by the disagreement between theorists and simulation theorists. The former hold that we come to understand the actions of others by way of inference from acquired or innate theory known as ‘folk psychology’.

( In philosophy of mind and cognitive science, folk psychology, or commonsense psychology, is a human capacity to explain and predict the behavior and mental state of other people.)

By contrast philosophers such as Robert M Gordon and Alvin Goldman insist that we explain other peoples behaviors by “putting ourselves in their shoes ie by running mental simulations of their mental states. Some versions of simulation theory are based on nueroscientific evidence, in particular on evidence linking mental simulations with the firing of so called “mirror-neurons”

Gallagher and Zahaui work is a deliberate attempt at linking cognitive-scientific research on consciousness, the self, perception, action and the understanding of other people’s mental states. They suggest a way of uniting this view with enactivism. They argue that as far as primary, bodily inter-subjectivity is concerned, there is no problem of ‘other minds’. Since as phenomenologists have long pointed out - we have direct access to other peoples bodily intentionality. This interaction involves simply a form of bodily attunement.

Stories play an important role in understanding other people’s behaviour. In the case of someones puzzling action, a narrative can facilitate understanding by filling in a rationale when it is not immediately obvious. Which goes back to the argument on Mental and semiotic representations. They exist in an object based schema and representation works by referring to a spatio-temporally locatable entity such as an existent or an event. Experience however, is a field of interaction and evaluation that cannot adequately be described in this object based term. The recipients experiences are often more complex than usually thought which has an implication on the relationship with stories as representational artifacts.

What are the expressive devices through which narrative can produce experiential responses in recipients / How can we encourage the audience to respond to the represented event and existent.

Our story cannot represent the characters experiences, but only events and actions whose experiential dimension is supplied by readers though their own familiarity with experience. The concept of expression plays a major role in my account of how experiences can be conveyed by semiotic and thereby representational artifacts.

Unlike representation, which works by refering to a self contained object, Expression is deeply embedded in the context in which an experience occurs. The main difficulty that arises is from our imagining of the experience. For instance pain is a concept we have a name for and therefore quite easy to grasp. If a heavy object falls on my foot i may experience pain and yell out. the yell is an expression, not a representation of pain because it is a way of reacting to an experience that is inextricable from it’s context.

Caracciolo argues that for expressions of experience to be understood one must have found themselves in a sufficiently similar situation Thus we can invite someone to imaginatively respond to something on the basis of his or her past experiences. When we see a heavy object fall on someone, those responses are often unavoidable as it isn’t uncommon to experience something similar to pain that manifests in a twitch or wince - a reaction that signals that we are imaginatively experiencing the other persons pain. the experience does not lie within the foot, nor the object, nor the fall, but in the way these objects interact with the subject and with his or her neural wiring.

Memory traces or experiential traces trigger the sensory residue left by a large number of past occurences.

In sum, representation and expression are different layers or aspects of the same process of engaging with stories (intertwined). Language is inherently representational, because it asks interpreters to think about - or direct their conciousness to - mental objects like events and existents . But it is also experiential because it can express experiences by constantly referring back to the past experiences of the interpreters, and by inviting them to respond in certain ways. Note that representation does not come in degrees: something is representational or not. By contrast the experiences created by stories vary considerably in intensity, depending on the strength of the interpreters responses, which in turn reflect the tension between their past experiences and the textual design.

.

0 notes