#meatcinema

Text

Rebecca: Framing a Dead Woman

When describing this film to others, I often call it a “ghost film without a ghost.” For those unfamiliar, the film centers around newlywed Mrs. de Winter as she accompanies her husband, the widower Maxim de Winter, back to his estate, the site where his former wife Rebecca met her fate. There, Mrs. de Winter must face the memory of Rebecca, the shadowy secrets of her new husband, and the threatening housekeeper, Mrs. Danvers. I find it to be one of Hitchcock's most tightly woven films, marrying his technique with the narrative in such a haunting, profound way. It is my favorite Hitchcock film. See below for my analysis, spoilers ahead.

One of the most spectacular aspects of Rebecca is the onscreen absence/presence of the titular character herself. Rebecca is interwoven throughout the film text as a visual presence, although her form is not physically available in the onscreen space. As we venture into the dark halls of Manderley, we are privy to the notable lack of Rebecca as a physical body, however, are constantly reminded that she is nearly always present in the visual text. Through mise-en-scène, cinematography, and onscreen “empty” space, Hitchcock creates an overwhelmingly dark portrait of a woman through filmic language.

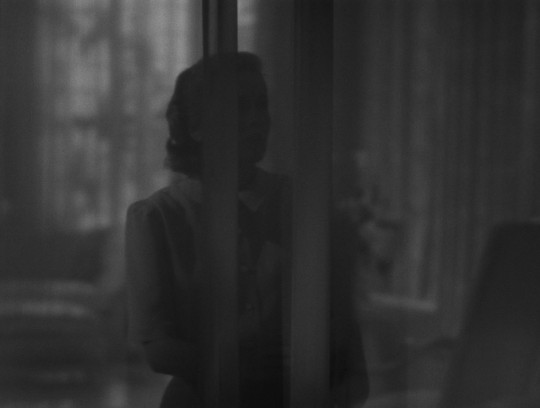

Although mise-en-scène is rather noticeable in the props used within any given scene in Rebecca, I would like to focus on the particular use of low-key lighting and dramatic shadow used to portray an external presence within Manderley. After Mrs. de Winter’s initial introduction to the house, in which she relinquishes all household duties to Mrs. Danvers, Danvers escorts her downstairs. In this scene, our protagonist is overlaid by dramatic shadows of the architecture of the house, its literal non-physicality swallowing her form. As we follow her down the hallways, her shadow follows her, moving across the walls, and when her shadow disappears, Danvers’ shadow appears. There is always a third person within the scene, that of the shadow, its physicality both a presence and non-presence in and of itself. We see Mrs. de Winter literally overshadowed by her counterpart, always being followed, always aware of the presence that is an absence.

Within these scenes, we also become aware of the camera movements through the dark hallways. Mrs. de Winter never occupies the middle of the frame, rather she clings to the left side of our field of view, while Mrs. Danvers’ eerily floats behind her on the right side. The middle of the frame is reserved for the shadow, the manifestation of the “third woman,” and indeed the most ominous of the trio. The camera centers on the middle figure, even as Mrs. de Winter and Mrs. Danvers reach the stairway. Their figures frame the doorway to Rebecca’s room— she is still present in the scene, even though her shadow figure is gone. Even as Mrs. de Winter and Danvers leave the shot, the camera pulls in towards the door, giving the architecture the emphasis it requires for the character it stands in for.

The door is later opened by Mrs. de Winter, and here we see the emphasis of light and shadow in a more bodily form to represent Rebecca. As Tania Modleski points out, “What is interesting about Rebecca […] is that it makes the tendency of women to merge with other women,” (Modleski, “Woman and the Labyrinth: Rebecca,” pg. 44). This shift of identification between protagonist/present with antagonist/absent and antagonist/present with antagonist/absent, is one of the more insidious aspects within the film. The scene in Rebecca’s room shows the very jumbled and frightening melding of identities between all three women. Modleski goes on to say about the scene “[…] Mrs. Danvers is really willing her to substitute her body for the body of Rebecca,” (Modleski, “Woman and the Labyrinth: Rebecca,” pg. 48). Within the scene we see Mrs. de Winter’s body in place of Rebecca’s as she is swept through the room by Danvers; she sits where Rebecca has sat, she feels Rebecca’s coat on her face, the absence of body in the clothes shown is almost overwhelming, she gazes upon the portrait of her husband, Rebecca’s husband. The cross between identities is dizzying.

However, what is most interesting to me within this scene, is the way in which Danvers herself is presented in bodily form as a Rebecca stand-in. As Mrs. de Winter gazes out her window, she sees a woman closing Rebecca’s bedroom window. This is the first instance of mixing Danvers bodily form with that of Rebecca’s. When she enters the room herself, she is startled by a voice behind her. In the dark, hazy light of the room, and shrouded in a dreamlike sheath of gauzy curtains, Mrs. Danvers appears as a silhouette. Her form here is indistinguishable, vague, she could be herself, she could be Rebecca, and for a moment, she inhabits both as a singular yet liminal body. It is only when she emerges from the curtain that she is revealed to be antagonist/present rather than antagonist/absent.

This silhouetting becomes a motif throughout the film, when the bodies of the women/present are presented in shadow to become the liminal space in which they embody woman/absent. After Mrs. de Winter is rejected from the costume ball, after she has been rejected for wearing the “skin” of Rebecca, and after the ship has hit the rocks, saving her from being goaded out the window, she wanders the foggy beach in silhouette.

It is in this scene where she becomes most liminal, she cannot fulfill her role as Rebecca, and she cannot fulfill her role as herself, and as she looks for her (absent) husband, she is portrayed in silhouette form- where she is in-between absent and present. The silhouette comes back in the final moments of the film, with Mrs. Danvers in the burning windows of Rebecca’s room. The final burning of Danvers, and her silhouetted bodily form- is the symbol of Rebecca’s final demise. We must also note the veiling of the women in these scenes by there-but-not-there materials: gauze, fog, and smoke.

Perhaps the most notable moment of camerawork is the scene in which the camera follows the empty space Rebecca once inhabited as Mr. de Winter recounts her final moments. It parallels the opening cinematography of the film, the camera gliding through a misty forest to settle upon the ruins of Manderley. It follows a woman, absent. What is also noticeably absent within the film text is Mrs. de Winter’s name- she has no identity prior to marrying Maxim- neither a first name nor a maiden name. The one piece of identity she has—her new name—she shares with Rebecca. It is through these techniques, specifically of lighting and camerawork, that Hitchcock presents us with a troubling and eerie absence as a character itself. The absence is never not noticeable.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

for some reason i deleted my letterboxd a few years ago but im back and slowly working on rating all my watched movies/building my lists/thinking about reviews i want to write, but please add me i want to see what y’all are watching!!!!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rear Window: Gaze and Power

I find myself preoccupied by the nature of the screen and our function in relation to it. It's strange isn't it? There's an intimacy between film and viewer that is at once familiar and distant. We play our role of watching the film and in doing so, we give the film purpose. Films are meant to be watched and we watch them. But there's also the distance, the separation of the audience, faces pressed against the screen as to panes of glass, only ever observers and never participants. There is a power imbalance that is constantly swaying between us and the screen, which makes which vulnerable, which makes which naked and seen? Which gives and which takes? And for this reason I find myself constantly returning to films that draw attention to our relationship with the screen.

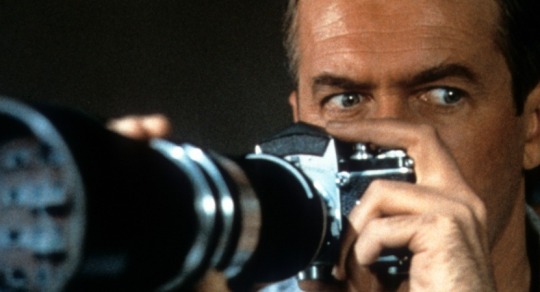

Rear Window is one of those films. For those unfamiliar, the film centers around a photographer, homebound by a broken leg, passing the time by spying on his neighbors through their windows until one evening he becomes convinced he has witnessed a murder. Hitchcock's run of films starring Jimmy Stewart tend to be some of his most manipulative. I find them as well to be some of his most gender-y work, often subverting gender roles both narratively and through his structure of the films. Rear Window, in my opinion, is a stunning example of the meta nature of cinema, particularly in regards to how gender plays into our role as the audience. There is coding to the camera, to where it points, how it looks, and thus, how we interpret the information we're being given.

(Spoilers below)

Within Rear Window, we are privy to a distinct sense of voyeurism that is layered within its approach. Hitchcock uses the film to point to the ways in which the audience participates as movie-goers in a gaze that is simultaneously active and passive. Throughout the film, it is most notable that the many women that Jeff watches through his window are framed in a way that subverts the male gaze. However, through the use of montage, Hitchcock critiques the male gaze through which Jeff operates. Throughout the narrative and dialogue, Hitchcock is able to allude to the viciousness of the gaze, particularly regarding the way women are presented on screen. In this way, Rear Window at once presents a strong opposition to the male gaze, while also creating a filmic experience in which the audience is forced to engage in and react to the various types of voyeurism presented, calling into question our own culpability as viewers.

Within Rear Window, we take Jeff’s perspective as he watches out the window. The camera position is consistent—at a distance. Any perceived objectification of the women Jeff monitors is due to the audience’s moral judgment of his reactions, not through the camera itself. The camera resists dismemberment, choosing to display characters like Miss Torso and Miss Lonelyhearts from the feet or knees up. The camera does not ogle at their bodies and their various parts—a thigh, lips, a breast, a stomach—but rather displays their complete bodies at a distance, allowing for the image to resist the typical male gaze in which women’s fragmented bodies are displayed as spectacle for men’s pleasure. We, like Jeff, are seeing them through a lens, and the distance placed between us and the women in the windows is enough to neutralize the gaze, to frame them in a non-sexual manner. However, the audience must discover how their gaze operates within this distance, causing us to question our own perception of the women we watch. Hitchcock asks us how we perceive Miss Torso as she dances or undresses when she believes no one else is watching—is this a sexual act or an innocent one? We determine the perversity of our own gaze, and we, like Jeff, are asked to question our own morality within the simple act of looking.

Although the camera itself resists dismemberment, the connection between dismemberment and women’s bodies under the gaze becomes apparent through dialogue and plot points. Throughout the film, there is an emphasis on the idea of women as body parts, both metaphorically and literally dismembered. Mrs. Thorwald’s body parts are carried out of her apartment in pieces, as well as buried in the garden. The affectionate name “Miss Torso” conjures a grisly image of a body without limbs. John Falwell notes “Jeff, in gazing at Miss Torso, is disturbed not by erotic thoughts but by violent ones […] Hitchcock draws a parallel, as he would often in his films, between sex and dismemberment, as if to suggest that sexual impulses are not far removed from violent ones” (Falwell, Torturing Women and Mocking Men: Hitchcock’s Rear Window, pg. 102). By alluding to dismemberment while also commenting on the perversity of Jeff’s gaze, Hitchcock demonstrates a strong defiance of the male gaze. The gaze itself becomes simultaneously sexual and violent within the context of the film, while the camera demonstrates great restraint in presenting the women in the windows through a non-sexual/non-violent lens.

Jeff’s stagnancy throughout the film is also quite notable in critiquing several aspects of the way our gaze operates within the film. Hitchcock comments on his use of montage, “Now if you took away the centerpiece of film and substituted—we’ll say—a shot of the girl Miss Torso in a bikini, instead of being a benevolent gentleman he’s now a dirty old man. And you’ve only changed one piece of film, you haven’t changed his look or his reaction” (Hitchcock, Rear Window, pg. 40). As an audience, our reaction to what we’re being shown often hinges on the way we perceive Jeff’s reaction. At times, Miss Torso’s dancing in her apartment becomes a pleasurable experience; however, it is our reaction to Jeff’s that determines how we look at both Miss Torso and Jeff. By placing the morality of the action onto the viewer, we become active participants within the film space, contrasting the passivity of Jeff’s singular unmoving position throughout the film. His inactivity becomes a kind of layered commentary on the type of voyeurism presented within the film. Falwell comments on Jeff’s alter identity across the way as both he and Thorwald sit silently in the dark (Falwell, Torturing Women and Mocking Men: Hitchcock’s Rear Window, pg. 97), and indeed the audience takes place in this commentary as well. Aren’t we also sitting silently in the dark, watching, waiting? In this way, both these men become our identities, our mirror doubles within the film space. Their voyeurism and its implications towards the women on screen become our voyeurism as well. While the women within the film—particularly Lisa and Stella—are able to navigate space in a way that Jeff cannot, we, too, are stuck in our seats, placing our hope within the active characters, the moveable characters: notably, the women characters.

With Rear Window, Hitchcock creates a heavily nuanced depiction of the filmgoer’s power within film. We sit, we watch, we gaze, and often, we are not aware of the power (or the lack thereof) we have within the screen world. He simultaneously makes us aware of the power held within our ability to look, and what our looking can do regarding the onscreen space and also makes us aware of how powerless our passivity as viewers makes us. By doing so, he creates a film in which women are not objectified by the camera, adeptly defying and critiquing the male gaze. Within the film, he gives power to the female characters—he makes them mobile, while rendering us immobile, and he makes them able, calling attention to our utter inability to sway the action onscreen. We become Jeff and the coded maleness of our gaze is rendered weak, even when the viciousness of the gaze becomes apparent through dialogue. The women of this film are at the forefront, and Hitchcock forces the audience to question their place within the filmic experience.

In the past few years I seem to keep finding my way back to Rear Window. During the pandemic, it was a film that came to feel relevant in how my gaze in began to operate in the real world. Trapped inside, staring out, always staring out. Beyond the glass, there were windows, snippets of other people's lives, lives that seemingly continued even while mine felt as though it were gradually grinding to a stop. And even in my relationship to film, the screen became another window, another place to watch a life I once knew slip away, to be somehow incapable of saving it. The film is perhaps one of Hitchcock's most prescient exercises in the nature of our relationship to cinema. We watch a film, and so often we don't think about the power that's held by the audience, or the power that's stripped away.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

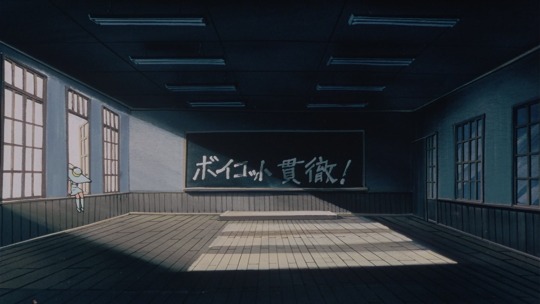

Battle Royale (2000) Dir. Kinji Fukasaku

Trigger warning for: Violence, Suicide, Sexual Assault, Murder

I first watched Battle Royale in high school, on my laptop, curled up in bed, at some secret hour of the night when I should have been asleep. I probably had school in the morning. I won't lie to you and say I was immediately swept off my feet, my head was still full of YA fantasy novels and what kissing must feel like and what it must be like to really date a vampire and still figuring out the logistics of periods and why I could never seem to insert a tampon correctly even though all my friends used tampons. I really liked it, but I sort of really liked everything back then.

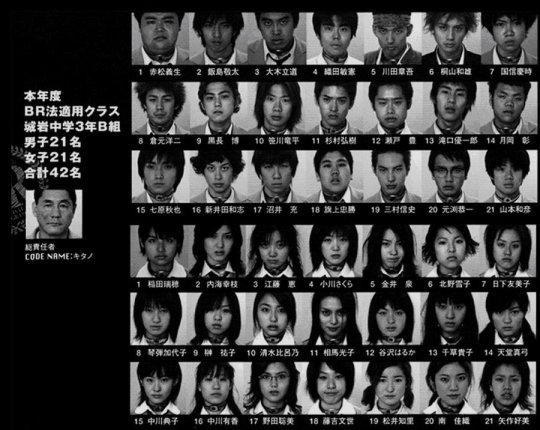

In college one of my very good friends asked me if I had ever read the book. I hadn't. He described the poetic language, the fluid grip of each page, and heartbreakingly, a moment I could scarcely remember from the film, two young lovers who take each other's hand and step off a cliff together. I would eventually read the book, my own printed grid of all the faces and numbers of the students acting as my bookmark. I would cross out their faces every time one of them perished. A sick game of bingo. I devoured all 627 pages in a little over 3 days. And it stuck.

I have watched Battle Royale many times since. I think every time I watch it, I hold it more and more dearly to my heart. If you're not familiar, Battle Royale revolves around a class of middle schoolers with explosive collars strapped to their necks, who have been selected to participate in the government sanctioned Battle Royale where they are tasked with killing each other until only one remains. It is a spectacle of bloodshed, darkly comedic at times, and deeply heartbreaking.

(Spoilers below)

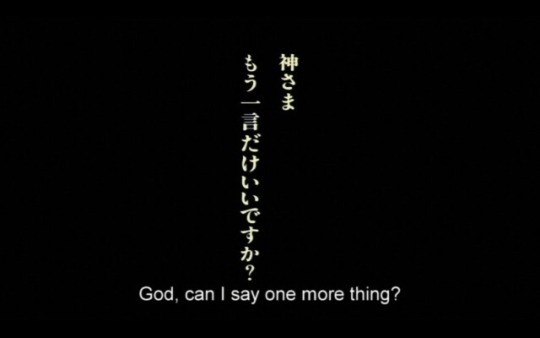

The film is constantly swelling with strings, operatic in its death and destruction, bloodstained uniforms and lush greenery, the constant churning of waves against the cliffside, it is as beautiful as it is violent. But where Battle Royale really strikes is in the quiet moments, after the screaming stops. There is a tenderness in the quiet, where minimalistic dialogue shines through. Chigusa lays dying in her crush's arms, understanding that he may never love her in the way she wanted, but this closeness, maybe it's not the worst way to die. She asks "God, can I say one more thing?" She tells him "You look really cool, Hiroki," and he responds "You too. You're the coolest girl in the world." They are no older than 14 or 15. The camera pushes out, framing them as part of the landscape, swaddled in crawling green, the light gold, the air still. There is such a sweetness in the words, such simple phrasing for such complex emotions, all the sincerity of a child confessing her love in the way she knows how, all the comfort of a boy who said he'd always have her back, forever, he promised. It is the quietest death in the film.

The film is intercut with moments like this, black screens of text, sometimes narrated by one of the characters, sometimes completely silent. There are also flashbacks, continually going back to the shared blurry golden memory of a basketball game, the entire class cheering and clapping, together in a moment of joy. Our protagonist Shuya remembers bunking with his best friend Nobu, the light melting through the window warm and comforting. Nobu is one of the first to die, his throat exploding as he reaches out to Shuya, and Shuya out to him. They scream for each other.

Sometimes the film is unimaginably cruel. One of the students holds a megaphone to his victim so her dying screams can be heard across the island. Mitsuko, one of the film's primary antagonists, revels in her own cruelty, delighting in the bloodshed. "What's wrong with killing? Everyone's got their reasons," she says pointing a gun at one of her friends. Not all memories are golden, Mitsuko proves. We are given a snippet of her childhood, her mother passed out on the kitchen table after selling her daughter to a strange man for the next few hours. During her first kill, Mitsuko tells her victim about a couple hanging from a tree outside. "Not my scene!" she declares, "I'll never die like THAT!" Some of these students have been surviving long before the game started. And for all her viciousness, all her mercilessness, Mitsuko delivers perhaps one of the most heartbreaking scenes in the film. She is shot. She gets back up. She is shot again. She gets back up. She is shot again. She doesn't get back up. It is in this moment that her desperation to survive is at its most apparent, she is flailing, screaming, covered in her own blood, but she will not give up. She has to survive, she always has. But she doesn't. Her body floats limply, her voice lays sadly across the frame "I just didn't want to be a loser anymore."

The film delivers some of it's most brutal dialogue in the moments of silence, often swallowing the students in scenery, framing them as part of the landscape. It's beautiful to behold, large sweeping grassy cliffs and the endless blue ocean and dripping green forests and dark deserted buildings in ruins. Hiroki lies dying after being shot by his crush who unknowingly perceived him as a threat. His chest bleeds as he confesses "I've been in love with you, Kotohiki, for a long, long time." He dies, his face half submerged in the dirty water flooding the floor of the abandoned building. One wonders what a "long, long time" must mean to someone who has lived such a short life. The water is red now. In many ways, the students seem to meld into the scenery, their bodies finishing the composition as if they were always meant to be there, as if there was never a way for them to escape.

The movie is brutal, grand, horrifying. It is as stark in its savagery as it is in its poetics. Below the mind-scrambling depictions of murder and death and the chaotic spiral of madness, lies a true tenderness for life, for friendship, for humanity. Towards the end of the film, the screen reads "At the end, I'm glad I found a true friend." There is such a ferocity for life in this film, for survival, that even in the bleakest of moments we can "RUN!" What is your life worth? Is it worth it to spend your dying moments in the arms of your best friend, to sacrifice yourself so your friends can survive, to tell the person you love that you loved them for a long, long time. Is it worth it to kill everyone you ever knew, if it meant you could go on, you could survive like you've always done. Is it worth it, just to know that you found a true friend. Through all the blood, all the guts, there is beauty to be found. There is something to run towards, just as there is something to run away from. Chigusa's memory unfolds as she runs through the forest, Hiroki close on her heels on a bicycle.

"Chigusa, how far are you planning to run?"

"Ahead of you, forever!"

"I'll watch your back forever."

"Promise?"

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

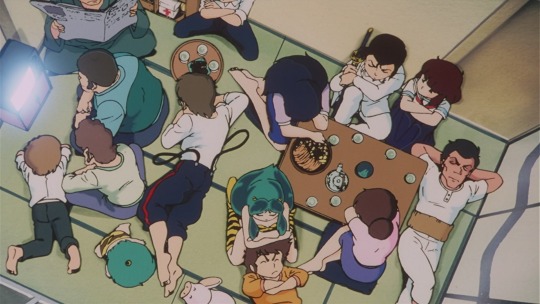

Beautiful Dreamer: Landscaping Liminality

I'm not sure where to start with Urusei Yatsura 2: Beautiful Dreamer. I suppose I should start by stating that this is the only Urusei Yatsura property I have consumed. I have not watched the series, the other movies, or read the manga. This film is my only exposure to Urusei Yatsura outside of some simple background research. Given that context, I would like to go out on a limb and say that in my opinion, I believe this film can act as a stand alone, although I'm sure there's bound to be difference of opinion with fans of the property. However, as a film, it's one that tends to fly under the radar despite its status of influence. One could draw back any handful of dream-focused or recurring-day films and properties to Urusei Yatsura 2.

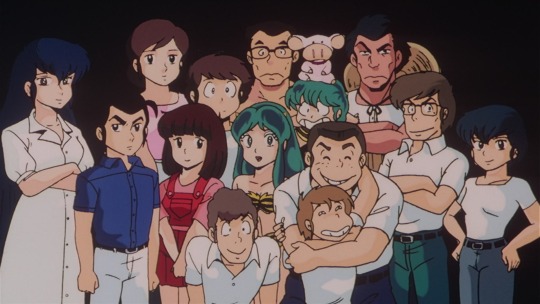

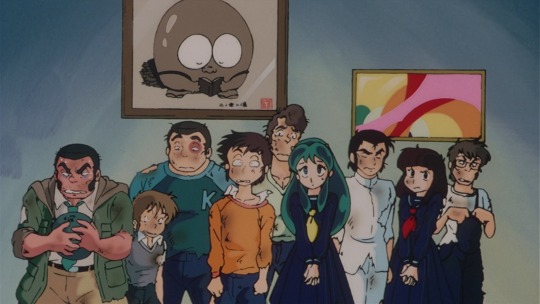

For those unfamiliar with the film, it revolves around Lum, a teenaged alien, and her friends as they start to notice strange occurrences in their town and lives. I don't want to give too much away if you have not seen it. It remains to this day one of my favorite animated films, and one that I excitedly pull out whenever I've met someone who hasn't seen it. It is strikingly beautiful, with a certain humor and charm, while also maintaining its philosophical surreal qualities and themes. See below the cut for my analysis, and be warned: spoilers ahead.

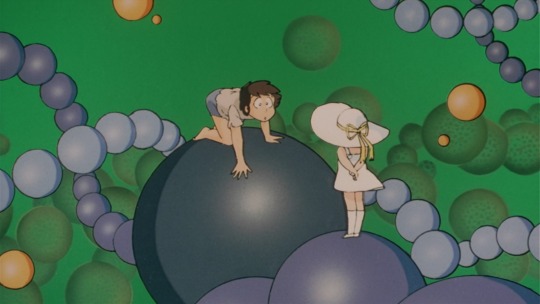

Within the film Urusei Yatsura 2: Beautiful Dreamer, the audience experiences a constructed space, one which lies in both reality and unreality. This in-between world is one in which our characters become conscious of their surroundings, yet they exercise little control over them. This particular space and the techniques used within the animation to portray its ambiguity, along with the constant themes of time construction and dream states, present the audience with a specific world in which liminality becomes the entire visual and emotional experience. The character Lum’s experience within a transitional space and transitional body is one that permeates throughout the film as her subconscious attempts to exude control in a real world in which her physical and emotional experience is threatened by the completion of her metamorphosis. Her transitional position as a teenage girl, an alien attempting to assimilate to human society, and within her complicated relationship with love interest Ataru, inspire her invisible desires to inhabit a space on the brink of unreality, in which change cannot

happen without her consent, unknowingly forcing her friends and the audience into her experience on the threshold of great change and the anxiety it stirs within her. Although she is not a protagonist that is followed throughout the film, the world that is constructed is one specifically fabricated out of her desire, her want, and her fears, and the protagonists become vessels through which the audience must navigate the expressed landscape of her interiority.

Lum is a character that does not occupy much screen space. Her placement on screen is usually that of accessory to those around her. With her vibrant turquoise hair and horns, occasionally wearing her tiger-striped bikini, her body is markedly different from those around her. Her body is also imbued with much more power than her peers—she can fly and emit an electrical shock, however these powers are not often used to progress her situation as much as they are to punish Ataru for his advances onto other women. She stands apart from these other women, in the way her body is more often on display, as well as with the more magical qualities she uses within her everyday life. However, the fact that she must contend with the other female characters on screen—female characters that possess qualities far more similar to their male counterparts than she does—presents a conflict within the way Lum’s character is perceived by

others. She is thrown into an uncomfortable limbo in which she is constantly pursued by the men around her, yet becomes the one woman Ataru desperately attempts to distance himself from. Susan J. Napier is quoted in “Anime’s Bodies,” noting upon this type of magical girl as characters that “all possess some form of psychic or occult power […] at the same time as they can be seen as intimately related with a young girl’s normal femininity,” (qtd. in Denison,

“Anime’s Bodies,” 2015, pg. 56). While she may not occupy the same type of screen space as the other female characters, she is inherently the main point of focus through their many adventures. Her power and her body specify her as the notable divergent from the norm, and that difference defines the space in which her deepest desires are made reality, desires that are very much rooted in her anxieties over the end of the liminal status in which she operates.

Lum’s wish is for stasis within her transformative period. As a teenage girl, her body is one that is undergoing rapid changes, and as an alien growing accustomed to life on Earth, the family she has found in her friends provides great stability in her social standing. Ataru’s constant chasing after other women threatens her security within her relationship, one she knows will sooner or later have to change. Through these drastic changes, she finds herself in a transitional space in which she exudes little control over her surroundings or the people around her. In many ways, she is hesitant to give up this in-between space, a place where she does not have the responsibilities of an adult, but also enjoys more independence than a child. As Denison notes “[T]he shōjo category of anime is invested within the liminal status of women’s bodies, held in tension between male and female or young girl and adulthood,” (Denison, “Anime’s Bodies,” 2015, pg. 58). The completion of such a transformative period becomes the most imminent threat to her security, and therefore her deepest desire is to remain the same and to resist the oncoming change. Through this desire, her dream is formed, a literal, physical world constructed out of her invisible wants and anxieties. This world, borrowing from the reality she knows and materializing the unreality she craves, is one that continues to shift and change as her friends get closer to finding out the truth of their experience within her world. As they navigate her spatialized interiority, the transformations to the world around them can be seen as literal changes to her psyche as she desperately clings to the normality of her social sphere.

The world that is built around Lum’s desire is one that at first entirely mimics the very real setting of the last day before the school festival. Here, she admits her dream out loud to Shinobu, “I want to live happily ever after with Darling, Mother and Father, Ten, Shuutarou, Megane, and all his friends. That’s my dream.” Shinobu responds “What?! That’s no different from how things are now!” We are then repeatedly drawn into experiencing this day, until Onsen-Mark's body can no longer handle the stress of the repetition. There is a repeated focus on the clockface without any hands, that chimes at unexpected times, lending to the sense of time construction that disorients both the characters and the viewers. In addition, Lum’s world has been constructed in a vaguely summery season, with the pleasant hum of cicadas droning in the background and decadent hazy green light blurring through windows. However, it is notable that this summer is inconsistent in its portrayal—the nighttime adopting shades of greys, blues and browns that are more consistent with winter, Ataru donning a scarf to fetch snacks with Mendou, culture festivals most often taking place in the fall season for Japanese students. It seems almost to be a mix and match of seasonal markers, one that is as sentimental as it is unsettling. This world is one that is wrong from the start; even within its façade of normalcy, there are subtle visual cues that stir a disturbance within the viewer’s experience.

One of the most primary ways this is done is by the animation of light. There are several times where unfamiliar light produces a distinctly surreal or dreamlike setting. Perhaps the most

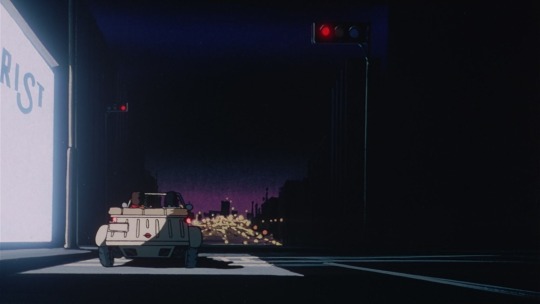

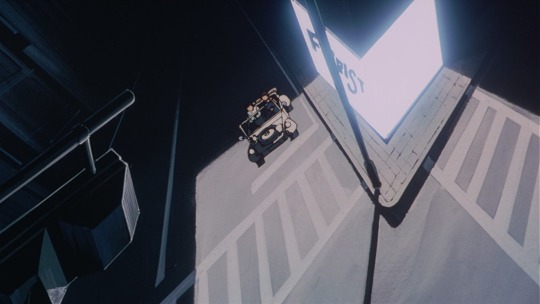

notable use of light comes from the floral shop as Ataru and Mendou are stopped at an intersection. The bright, white light from the building contrasts with the darkness that surrounds them, the scene shot from various canted angles. This is the first introduction of Young Lum, as she follows behind the faceless special-sales band. The scene unveils a particularly quiet sense of the uncanny; it is something distinctly out of the ordinary but still familiar enough as to not instill panic. Later, as Mendou and Shinobu attempt to make their way home, the headlights from their car presents an eerie and unfamiliar perspective. The bright yellow circle that scans across the ground at a rapid pace, revealing dead end after dead end, turn after turn, does instill panic within both the characters as they find themselves lost within the labyrinthine construction of Lum’s dream world. These scenes are particularly notable within their animation and use of light to convey an unsettling and mysterious atmosphere among the surface level normality of this singular day.

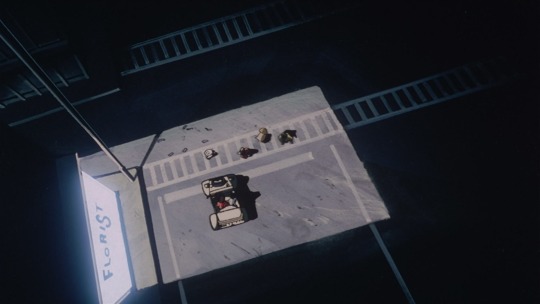

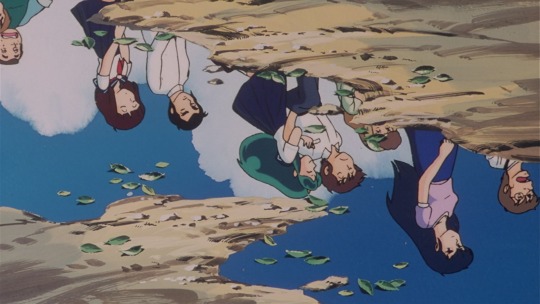

Throughout the film, there is use of reflection/refraction imagery to both highlight what is askew within the world and to emphasize a specific duality within the characters and their environment. As Ataru and Mendou drive to get snacks, he comments on how quiet the night is, looking out at his reflection in passing windows. When Onsen-Mark reveals his memory loss and the repetition of time, he is framed through a glass, Sakura pouring water into it, refracting his face to reveal a man transformed by this epiphany. The team is reflected through puddles on the ground, leaves suspended on the surface, Ataru physically sinking and disappearing through the surface of one. As they investigate the school, Ataru finds himself literally reflected through an infinite tunnel. As Mendou comes to his final realization that Lum is the dreamer of this world they cannot escape, he is surrounded by a large silvery puddle reflecting the sky beneath his feet—yes, he is in a dream, and the very ground he stands on confirms this suspicion. These instances of reflection and refraction can be seen as the characters’ inner introspection on their place within this world, as well as their revelation of what being a person in Lum’s life may mean. While characters like Ataru are duplicated infinitely, it is notable that Onsen-Mark after his refraction becomes a pillar holding the town upon the turtle’s back and Mendou, who has spent the infinite days of summer pleasure seeking the truth, is not reflected in his revelation of whose dream he inhabits. This sense of duality that becomes a constant motif comes down the Lum’s own duality and her occupation of a space between these two poles.

Lum appears to the audience in two forms: her teenaged body, and her dream body in the guise of Young Lum. Young Lum appears in spaces of transition, places where she is most comfortable, signaling her as a physical manifestation of Lum’s desire to inhabit liminality. She is seen at the red light of an intersection, in an empty classroom, looking out the window of a train at night, skipping after a bell cart through the spaces in between houses. She is a child, often faceless behind a white sun hat, she denotes a specific sense of frivolity and wonderment at the world she inhabits. Sharon Kinsella notes upon the strive for childish attitudes within Japanese cute style:

This childlike state was considered to be innocent, natural and unconscious. And it was one in which people expressed genuine warm feelings and love for one another. But most of the time this expressive emotional state was hidden, trapped inside each individual and something not often visible to other people.

(Kinsella, Cuties in Japan, 1995, pg. 240)

Ostensibly, Young Lum can be considered as Lum’s hidden emotional state, able to express her desires out loud where Lum in reality could not. When Ataru is trapped within his own dream, stuck on giant strands of swirling DNA, she appears to him, revealing the secret of waking up. She says he must call out the name of who he wants to see most, and she asks him, revealing her face, to do the right thing. Within this scene we can see that Lum’s truest desire, at DNA level, is for Ataru to do the right thing. While Lum’s teen self was able to obliviously enjoy the pleasures presented by her dream world while unable to fully comprehend her surrounding environment, Young Lum’s body is situated as one that is able to express her emotional plea to Ataru, while maintaining and innocent and unassuming childlike form. Between these two poles of self is the space in which real Lum is situated—on one side the blind pleasures, and on the other, the deep and expressive desire.

Urusei Yatsura 2: Beautiful Dreamer is a film teeming with imagery and themes that continue to impress upon every viewing. Through film techniques that emphasize light, the motifs of refraction and reflection, and continuous disorientation of time and seasonal change, we are delved into a world that is both frightening in its complexity and pleasurable within its sentimentality. This dream world, on the brink of reality and unreality, is one that becomes gendered in its construction of Lum’s internal desire and her anxieties about her coming-of-age. She is a character that although does not occupy much screen space, becomes the central focus as we navigate the labyrinth of her spatialized interior life. Throughout the film, the world shifts and changes, giving access to the transformational quality of her emotions and body, and we become privy to the most invisible aspects of her personhood. Her position within the in-between state is one that becomes embodies our entire experience within the film—the space between dream and reality, awake and asleep, aware and unaware, fear and desire. Within this liminal space, we are allowed the privilege to literally place ourselves within her complex emotional state, and it is one that is as beautiful as it is mysterious.

Works Cited

Denison, Rayna. “Anime’s Bodies.” Anime: A Critical Introduction, Bloomsbury Academic, 2015.

Kinsella, Sharon. “Cuties in Japan.” Women, Media and Consumption in Japan, Curzon & Hawaii University Press, 1995.

Urusei Yatsura 2: Beautiful Dreamer. Directed by Mamoru Oshii, U.S. Manga Corp., 1984

22 notes

·

View notes

Note

Oh my goodness!!! Happy Birthday to my main source of incredibly specific and niche fob info! I hope you're having a wonderful meat day<3

p.s. ur one of the few people on here whose opinions on movies I'm actually excited to hear about, hope you come back to meatcinema sometime

APOLOGIES FOR THE LATE REPLY THANK YOU ❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️ I REALLY NEED TO WRITE ABOUT MOVIES AGAIN THANK YOU FOR REMINDING ME THAT I LIKE DOING THAT <33333

5 notes

·

View notes