#khorfakkan new attractions

Text

youtube

#Ugly And Traveling#khorfakkan#khorfakkan beach#khorfakkan waterfall#khorfakkan amphitheatre#khorfakkan sharjah#khorfakkan drone views#khorfakkan drone video#khorfakkan in 4K#khorfakkan amphitheatre drone views#khorfakkan amphitheatre drone video#khorfakkan tourist place#khorfakkan road#khorfakkan beach fujairah#khorfakkan amphitheater and waterfalls sharjah uae#khorfakkan new attractions#amphitheater khorfakkan#khorfakkan best places#khorfakkan corniche#uae#ugly & traveling#travel around the world#travel vlog#travel backpack#traveling vlog#travel blogger#uglyandtraveling#travel#travel channel#Youtube

0 notes

Photo

Gulftainer, the world’s largest privately-owned independent port operator and logistics company based in the UAE, finalised a 50-year concession with the State of Delaware in the USA to operate and develop the Port of Wilmington, significantly expanding the company’s global footprint and reach. The agreement, signed by Gulftainer’s subsidiary GT USA, will see an expected investment of up to $600 million in the port to upgrade and expand the terminal and to turn it into one of the largest facilities of its kind on the Eastern Seaboard.

Gulftainer

The port deal represents the largest operation ever run by a UAE company in the United States, as well as the largest investment ever by a private UAE company in the country.

At a public signing ceremony held in Wilmington, Governor John Carney of Delaware signed the agreement with Badr Jafar, Chairman of the Executive Board of Gulftainer, in the presence of Delaware Secretary of State Jeffrey Bullock and other state officials, as well as H.E. Yousef Al Otaiba, the UAE Ambassador to the US and other dignitaries.

The 50-year concession follows a year of negotiations and a thorough evaluation of Gulftainer’s capabilities globally, including in the USA, where it currently operates the Canaveral Cargo Terminal in Port Canaveral, Florida and provides services to the U.S. Armed Forces as well as the US Space Industry. The Delaware concession agreement completes a preliminary agreement between Gulftainer and the State of Delaware, as well as the completion of a formal review by the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), granting Gulftainer exclusive rights to manage the Port.

Badr Jafar, Chairman of Gulftainer s Executive Board and H E Yousef Al Otaiba, UAE Ambassador to the USA during the Gulftainer Signing Ceremony

Gov. John Carney, Governor of the State of Delaware, said: “This historic agreement will result in significant new investment in the Port of Wilmington, which has long been one of Delaware’s most important industrial job centers. For decades, jobs at the Port have helped stabilize Delaware families and the communities where they live. I was proud to help make our partnership with Gulftainer official today, and I want to thank members of the General Assembly, the Diamond State Port Corporation, Gulftainer, and all of our partners who have helped make this agreement a reality.”

Gulftainer plans to invest up to US$600 million in the port, including $400 million on a new 1.2 million TEU (twenty-foot equivalent units) container facility at DuPont’s former Edgemoor site, which was acquired by the Diamond State Port Corporation in 2016.

Badr Jafar, Chairman of Gulftainer’s Executive Board, said: “We are proud to be making this long-term commitment to the State of Delaware, its community and its economy. This landmark agreement builds on Gulftainer’s 43-year track record of delivering excellence and dependability in ports and logistics operations around the world, and we are confident that this public-private partnership will propel the Port of Wilmington towards becoming the principal gateway of the Eastern Seaboard.”

Mr Jafar added, “since Gulftainer’s entry into the US through our operations in Port Canaveral in 2015, we have discovered major untapped potential in this sector and we will continue to look for attractive investment opportunities in the region.”

H.E. Yousef Al Otaiba, UAE Ambassador to the USA said, “The UAE and US have a strong, vibrant investment relationship that delivers meaningful and measurable benefits to businesses, and creates jobs in both countries. Gulftainer’s investment in the Port of Wilmington is a perfect example of this important economic partnership. This deal will create new jobs in Wilmington and generate additional economic benefits to other communities across Delaware.”

Plans for the Port also include development of all cargo terminal capabilities at the facility and enhancement of its overall productivity. Gulftainer will also establish a training facility at the development site specifically for the Ports and Logistics industries that is expected to train and upskill up to 1,000 people per year.

Peter Richards, Group CEO of Gulftainer, said: “Gulftainer has been fortunate to be at the forefront of transforming port and logistics operations in four continents around the world. This deal is a milestone in our operating history, and will provide us the platform to make a real difference to the sector on the US East Coast by working closely with the State of Delaware to achieve significant enhancements across the board.”

The Port of Wilmington opened in 1923, and is a fully serviced deep-water port and marine terminal strategically located on 308 acres at the confluence of the Delaware and Christina Rivers. It is the top North American port for fresh fruit imports into the USA and has the largest dockside cold storage facility in the Country.

The relationship between the US and UAE has long been underpinned by a shared commitment to promote strong trade and investment ties. In recent years total bilateral trade between the UAE and US has grown from approximately $5 billion in 2004 to over $24 billion in 2017. The US had a $15.7 billion trade surplus with the UAE, its third largest trade surplus globally.

About Gulftainer

Gulftainer is the world’s largest privately owned independent port operator. Established in the Emirate of Sharjah in 1976, the rapidly expanding ports and logistics company has built up a strong presence in various parts of the world. In 2017 and 2016, The Seatrade Maritime Awards named Gulftainer the Terminal Operator of the Year in the Middle East, Indian Subcontinent and Africa region. Gulftainer won the ‘Technology Implementation of the Year’ category in the Logistics Middle East Awards 2017. It also won the Logistics Middle East CSR Initiative of the Year award in 2018.

In the UAE, the company operates two main ports on behalf of the Sharjah Port Authority –Sharjah Container Terminal (SCT) and Khorfakkan Container Terminal (KCT). Its flagship terminal, KCT, was recognised by the Journal of Commerce as the fastest terminal in the MENA region and the third-fastest in the world.

Outside the UAE, the Gulftainer Group operates and manages ports and logistics businesses in several countries including Iraq (Iraq Container Terminal, Iraq Project Terminal and Umm Qasr Logistics Centre), Pakistan (GTL-MTI), Brazil (Recife Port), Lebanon (Tripoli Container Terminal) and Turkey (Momentum Logistics). In Saudi Arabia, Gulftainer acquired a 51 per cent stake in Gulf Stevedoring Contracting Company (GSCCO) in June 2013, and now operates the Northern Container Terminal in Jeddah, Jubail Industrial Port and Jubail Commercial Port. Canaveral Cargo Terminal in Florida, USA, opened in June 2015 following the signing of a 35-year agreement that made Gulftainer the first port management company from the Middle East to operate in the United States.Currently handling an annual throughput of 5.2 million TEUs, Gulftainer aims to expand its global portfolio in the next 10 years to triple business volume worldwide to more than 10,000 vessel calls and triple container handling to 15 million TEUs.

About GT USA

GT USA is the U.S. division of Gulftainer, the world’s largest privately owned, independent terminal operating and logistics company with operations and business interests in the Middle East, the Mediterranean, Brazil and the United States. The company signed a 35-year agreement with the Canaveral Port Authority in Florida, marking Gulftainer’s first venture in the United States. In addition to containers, Canaveral Cargo Terminal also handles heavy equipment, vehicles and boats as well as breakbulk, lumber and heavy lift cargo. GT USA also manages a 40,000 square-foot warehouse at Port Canaveral.

The post Gulftainer Signs 50-year, $600 million concession to Operate and Expand Port of Wilmington in Delaware, USA appeared first on Dubai Blog.

0 notes

Text

We Need to Talk about the Modernism Fetish in the Gulf

fet·ish. ˈfediSH/: “… an object of irrational reverence or obsessive devotion”

Prologue

An assortment of headlines in UAE based, English language publications lamenting the loss of ‘historical structures’ and ‘icons.’

“Original Hard Rock Cafe in Dubai demolished after 15 years.” (built in 1998) “A Facebook campaign called Save the Hard Rock Cafe attracted about 6,000 supporters.” -- The National. January 28, 2013

“Dubai television tower demolished: The aging Jumeirah television tower was demolished on Friday, bringing an end to one of Dubai's iconic structures.” (Built in 1986) -- Gulf News, June 28, 2008

“End of the road for Dubai's Metropolitan hotel. Metropolitan hotel, one of Dubai's oldest hotels, is to be demolished next year.” (Built in 1978) -- The National. November 29, 2011

“Dubai's Metropolitan Hotel demolition: Heartache for people who made the job their life. The Metropolitan Hotel, which is due to be demolished, was like a family for many who worked there.” -- The National & Gulf News. March 8, 2012

“Dubai’s landmark ‘Sana Building’ to be pulled down. 35-storey twin tower to replace the iconic building in Dubai's Karama area.” (built around 1987) -- Gulf News. January 11, 2017

Figure 1. Clockwise from top left: Hard Rock Cafe; Jumeirah Antenna; Sana Building; Metropolitan Hotel

In 2014 at a fully packed NYU-AD auditorium I was participating in a panel put together by the publisher of the Abu Dhabi Architectural Guide.[1] A compendium of modernist buildings (anything built after 1966, more or less) its stated aim was a documentation of the city’s architectural heritage thus disputing the claim that Abu Dhabi has ‘no history.’ In my opening remarks I cautioned against the fetishization of buildings, i.e. the notion that one can become enamored with a structure, simply because it was built in the ‘past’ (the word past here needs to be taken with a great deal of caution) and thus elevate it to the status of sainthood. As an example I mentioned the Abu Dhabi Bus Terminal which opened in 1989 and was designed by a Bulgarian architectural outfit. It has acquired in the minds of the modernist brigade a kind of respect and reverence usually associated with Gothic cathedrals. To my mind it is not a particularly interesting building. Known mostly for its quirkily curved concrete canopy extending over the bus stops, and painted in a garish green color, it stands in opposition to its surroundings, visually speaking.

Talking about surroundings, the structure makes no gesture whatsoever towards the city in which it is located. The bus station is surrounded by a fence and is set back from the street and can thus be seen only from a distance. Surrounding open spaces are occupied by workers on many evenings imbuing it with a sense of informality largely absent from the city, and also suggesting the potential for such a building in attracting a larger segment of the population and becoming a vibrant social hub. Given all that, I argued that it is probably best if the building is demolished and a more appropriate replacement takes its place. A kind of porous urban structure as seen in many other parts of the world.

Figure 2. The Abu Dhabi Bus Terminal set back from the street. Source.

Having made that statement you could literally hear an inaudible gasp from the audience. It seems that I had defiled the holy grail of Abu Dhabi architectural modernity. It pretty much went downhill from there. Angry denunciations followed informing me about the building’s synthesis of both the Frank Lloyd Wright Guggenheim Museum in New York City and the Eero Saarinen Washington, DC airport terminal (why is that a good thing?); others pointed out that such views (mine) are reflective of a kind of drive-by mentality which does not understand the inherent beauty of the building (which was kind of my point, its remoteness and distance); or that Abu Dhabi is losing so much of its history that we need to preserve whatever is left (even if it is functionally inefficient, or lacks any connectivity to the city). A particularly irate audience member went off on a tangent and denounced modernism as a category (because I had mentioned in passing that modernism had admirable social goals); others (actually only one, in a face-to-face conversation after the event) praised my bravery for refusing to turn the city into some sort of fossilized version of itself (however hard that maybe in the case of Abu Dhabi). It seemed that I had touched a raw nerve – and in an attempt to placate an increasingly angry mob I noted that my comments were made partly in jest to make a larger point about modernism.

youtube

Video of the Event. Standard Disclaimer: Actual events may not correspond directly with my own hazy recollections.

What this episode illustrates though is that in the Gulf, and indeed throughout the world, modernism is making a strong comeback. In recent years there have been many initiatives and exhibitions that celebrated modernist ‘achievements.’ For instance the theme of the UAE National Pavilion at the 2014 Venice Architecture Biennale, was ‘Lest we Forget’ a nostalgia tinged celebration of the countries’ architecture, largely focused on what was produced in the 60s and 70s. A hit-parade of favorite buildings, masterplans and amusing anecdotes about the countries’ founders thus sustaining some sort of founding myth. Other efforts followed, such as the documentation of Sharjah’s modernist heritage. Accordingly, anything built in that golden age of modernism and has a slightly worn out look with curiously looking concrete apparitions is declared as a worthy masterpiece. I have been complacent in this as well, introducing the UAE Modern initiative in 2012, an educational project whose aim was to map modern architecture in the UAE. It had its share of trophy buildings – the World Trade Center, the Hilton Hotel in Al Ain – although in my defense students also examined other, less spectacular structures such as the New Calicut Hotel in Khorfakkan, the Breeze Motel in Kalba, gas stations, health centers and schools. None are particularly remarkable and may not be worthy of a second look by hardcore modernist aficionados. Yet they are a significant component of an Emirati Vernacular – an architecture that is derived and inspired by its users and inhabitants – rather than a top down version of an expatriate architect’s fantasy about what constitutes Emirati identity.

Figure 3. Timeline of remarkable buildings in the UAE. As shown in the UAE Pavilion at the 2014 Venice Architecture Biennale. (Source: Author)

Figure 4. Less remarkable buildings in the UAE. Clockwise from left: Calicut Hotel; Breeze Motel; a Gas Station. Source: UAE Modern

Such interest in glorifying and valorizing various modernisms is to some extent inspired by what is happening throughout the Arab World. For example, a center in Beirut that wants to be a repository of modern Arab architecture; in Cairo an architectural observatory outfit is engaged in a kind of navel-gazing of the city’s ‘golden architectural age’ – whatever that is. Numerous Facebook pages look at life in the ‘good old days.’ Some of those have found their way into a Gulf based architectural discourse. For instance the Bahrain Pavilion at the 2014 Venice Architectural Biennale is a homage of sorts to Arab Modernism designed and curated by folks from Beirut. This does of course raise the issue of context (and history). Clearly though no one can dispute the value of documentation, mapping and archiving but if they are not situated in a larger critical discourse can easily become tools for a more sinister agenda that seeks to dismantle the old and usher in a neo-liberal urbanity that furthers inequality, increases alienation and promotes a sense of transience and temporariness. By focusing on a few token buildings and structures, claiming that they are part of the nation’s ‘heritage’ and incurring a protective status on them, more serious damage is done to buildings that are more valuable socially and culturally.

There are countless examples for this. Consider the Central Market in Abu Dhabi. While modernist in appearance it transformed into an informal affair, bringing together a diverse group of residents. Or the Mulla building in Electra Street, Abu Dhabi. An unremarkable building from the 1980s, it was a gathering area for the city’s marginalized South Asian population containing an arcade that was a piece of South Asia in the middle of an Arab Gulf city. Both are not known for their outstanding or quirky architectural qualities but for their performative social roles. Both were demolished recently to be replaced with high-end developments that cater to the rich and privileged, furthering inequality and an overall sense of transience. But all this is good though because we have listed the bus stop as a modernist icon, so we are off the hook, in a manner of speaking.

Figure 5 & 6: The Abu Dhabi Central Market in 2004; and the Mulla Building 2008. Source: Author

The case of the UAE Sha’bī (or National house) is of particular relevance. It was the theme of the UAE Pavilion at the 2016 iteration of the Venice Architecture Biennale, which I curated. From the outset I sought to distance the exhibition from a nostalgia inspired presentation about the ‘good old days’ to one that highlights contemporary transformations. My focus was on how residents transformed their ‘modernist’ homes to make them compatible with their lifestyles and habits. It is not a glamorous architectural form or one that would attract the pages of glossy magazines yet it achieves a quality that is indigenous since it is a direct outcome of residents needs. It thus stands in defiance to the top down version of modernism. An architecture without architects – a true expression of a societies culture. This particular building type has received the attention of heritage conservationists but has as of yet to receive any sort of official recognition as a significant element in the nation’s built heritage. More significantly countless Sha’bī neighborhoods are left to decay and crumble, acquiring a slum-like status, a place to be shunned and filled with undesirables.

Figure 7: The UAE Sha’bi house across the nation; displayed during the 2016 Venice Architecture Biennale at the UAE National Pavilion. Figure 8: A deteriorating Sha’biyya neighborhood in Al-Ain. Source: Author

Things are not as dire as these examples may indicate however. In fact there are some success stories such as the preservation of the modernist Abu Dhabi Cultural Foundation. [2] Aesthetic qualities aside that building’s main value derived from being a social hub for the city’s residents (Emirati and expatriate alike) who banded together to save it from demolition. Moreover the building is not simply an object to be acquired like a luxurious car but it performed a significant role in the life of the city and was open to its streets with various passages linking it to the city.

Figure 9: The Abu Dhabi Cultural Foundation. A structure that is connected to the city. Source: Author.

At some level such an interest in modernism is quite curious. After all during the 1970s and 80s modern architecture was strongly maligned. All sorts of social ills were ascribed to this particular brand of architecture. Its monotony and simple forms were associated with a mind-numbing sameness and alienation among city dwellers. The abolition of walkable streets and communal spaces in favor of efficient highways was correlated will all sorts of urban problems such as crime. Writers, scholars and acitivist bent over backward decrying the evil that is modern architecture: Tom Wolfe in “From Bauhaus to Our House,” Robert Venturi’s “Learning from Las Vegas’ and of course the holy grail of anti-modernist city planning Jane Jacobs’ “Death and Life of Great American Cities.” At some point though over the last few years a shift happened. Worldwide there has been a resurgent interest in all things modern – architecture and otherwise. Mid-century modern became a style to be admired – furniture from that period acquired, adapted and placed in contemporary homes. Media joined the bandwagon – TV shows looking at the 1960s period highlighted its streamlined aesthetic and bright colors in shows such as “Mad Men” in which protagonists are seen wearing sleek suits, driving Cadillacs and entertaining in open air floorplans contained in Miesian skyscrapers. The 1950s and 60s were cool again.

Figure 10: Don Draper’s 1960 living room in ‘Mad Men.’ Mid-centruy modernist nostalgia. Source.

At an architectural level Brutalism in particular, with its aesthetically pleasing, overtly expressive concrete forms, captured the attention of many architecture aficionados. Websites such as “fuckyeahbrutalism” are filled with countless examples of buildings following this style popularized in the 1960s. Subject to demolition and replacement, efforts are made for preservation, although as some critics have pointed out the revival is a form of commodification that stands in opposition to the movement’s original progressive social agenda. [3] Yet aside from speculative motifs are there other explanations for looking to the past? Postmodern theorist Andreas Huyssen notes that there has been an “explosion of memory discourses at the end of the twentieth century.” [4] Others evoked the notion of an “invention of tradition,” a psychological device through which some aspects of the past are rejected to “validate the new, but sometimes also the retention of the past as ‘other’ as a continuing proof of the superiority of the new.” [5] Thus, a deep dissatisfaction with the present prompts a kind of collective effort to reminisce about the past.

How does the Arab Gulf fit in all of this? How can one explain the obsessive interest by some in preserving and mapping all things ‘modern.’ Is it simply a matter of copying what happens elsewhere in the region and the world? Or are there other factors at work? For longtime residents in the transient cities of the Gulf, evoking such nostalgic recollections may act as a form of resistance to obsolescence and disappearance. A counter narrative to temporariness. For Emiratis it may well be an attempt at creating an architectural heritage, a tradition of building that shows their society as equal to places elsewhere. This is irrespective of the fact that all of these ‘modernist buildings’ were built and designed by foreign architects. And they do not constitute a form of colonial architecture blending indigenous building traditions with modernist influences given the historical context of the region.

Rashad Bukhash, former head of conservation at Dubai Municipality and former member of the UAE Federal National Council is a champion of preserving the UAE’s architectural heritage. In a debate at the council he was questioned by a colleague about whether “there was an Emirati architectural style.” I have personally witnessed participants in workshops debating the very existence of an indigenous built heritage and the meaning of an “Emirati Identity.” Recently an Emirati commentator noted:

Our culture isn’t to be seen in buildings or items of art. We didn’t have museums, opera houses, government buildings or palaces. Our culture is to be found in our oral traditions, values, language, poetry and the history that has been handed down from generation to generation.

This notion of associating one’s culture with the expectations of others is problematic. Another Emirati commentator questions the need for utilizing foreign architects in designing such significant structures as the monument for fallen UAE soldiers in a CNN Arabic piece titled: “Why is it better to design the National Commemorative Monument by a Khaliji designer” (as opposed to the British national who was selected). These are important questions and a debate needs to take place about such matters. The Gulf has its own unique qualities and cultural traditions. An architecture will ultimately emerge that will reflect this – but for that to happen tools need to be provided, and a framework created, which would allow for a free expression of lifestyle, needs and activities (e.g.: proper architecture schools that are not western imports headed by outsiders; architectural societies that promote and engage in critical debates; an examination and celebration of an Emirati vernacular architectural tradition). Such a discourse is more meaningful, more sustainable and more relevant than simply enumerating and listing modernist imports that may or not be useful but that are not from this land. It is time to look to the future rather than the past and to empower Emiratis with the tools needed to participate in the production of their own built environment.

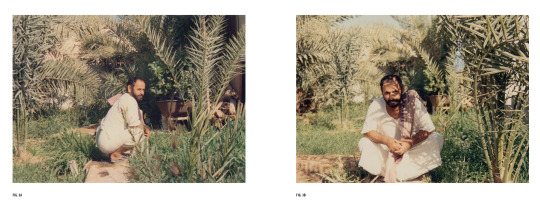

Figure 10: Head of the Meqbali household nurturing the garden of his Sha’bī house in the 1980s. When architecture fades and a house is transformed into a home. Source: NPUAE

Notes

[1] Menoret, Pascal (ed.). The Abu Dhabi Architectural Guide. Abu Dhabi: NYU-AD, FIND

[2] Designed by Iraqi architect Hisham Ashkouri, who was part of TAC (The Architects Collaborative) a Cambridge based firm founded by modernist icon Walter Gropius.

[3] Catherine Slessor (2017). “Brutalism is back – but its fetishisation comes at a cost”

https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/article/opinion-architecture-brutalism-and-the-future-of-housing

[4] Huyssen, Andreas. Present Pasts : Urban Palimpsests and the Politics of Memory, Cultural Memory in the Present. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 2003.

[5] Dennis, Richard. Cities in Modernity : Representations and Productions of Metropolitan Space, 1840-1930, Cambridge Studies in Historical Geography. Cambridge ; New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

0 notes