#jack rudin invitational

Text

Watch "Jack Rudin 2023.1.15 NCCU 10am session" on YouTube

youtube

0 notes

Text

Why Podcast Listening Is Such An Intimate Experience

There are numerous reasons why listening to podcasts is an intimate experience. Even companies that sell ads on podcasts find, in their research, that podcast fans have a special bond with podcasters. That's one reason why host-read ads resonate so well with listeners.

With podcasting, as with music, you can create your audio world with sound becoming your personal valet. No one knows what you're listening to unless you share that information. Listening to a podcast and music is indeed a much different experience. Music can facilitate a daydream, convey a mood you want to reproduce, or you can revel in the emotional cloth that music can provide.

Listening to a podcast offers a more intellectual, thoughtful, emotional, and informative experience.

You can think, reflect, laugh, scoff, snicker, scream, doubt, and believe.

For example, when I work in my garden a few times a week, The Daily with Michael Barbaro is my constant companion. If I'm driving in the evening, APM Marketplace rides with me in my Hyundai. I don't blast the speakers or dial up the bass to vibrate the interior to show off to others that I'm listening to music. Instead, I bath myself in the carefully considered words of Kai Ryssdal on Marketplace.

When I walk five miles almost every day (no walking in the rain or in extreme temperatures over 90 degrees and under 10 degrees), I can't wait to cycle through my favorite podcasts. As I move past houses in my neighborhood, I am treated to the words of Sean Rameswaram from Today, Explained or the true-crime podcast The Murder Sheet.

When people listen to music, there are often those visual cues they cannot help but display. A tap, tap, tap of your feet. A simulation of your hands playing drums on your thighs. A sway of your hips or a bob of your head.

The message to the outside world is clear.

"I'm listening to some great music, everyone."

When listening to a podcast like Slate's Hit Parade, it's just me and host Chris Molanphy geeking out the Billboard charts. Or Ken Rudin on The Political Junkie, giving me an insight into famous past events in political history.

A great podcast can capture your attention, such as Decoder Ring with Willa Paskin. You can be so focused on the words and sounds in the podcast and still be concentrating on cleaning the house, washing the car, cleaning out your closet, or even packing orders for your small business.

Listening to a podcast is an intimate experience between you, your ears, and the podcast host and guests. It's like inviting these people into your brain. They stay for a while, maybe an hour, and then leave you with some info, a few insights, a kernel of a new idea, a funny story, a tale of woe, or the sense that the wrong person was convicted.

So the next time, you carefully insert your earbuds, use your podcast app to decide upon a podcast, think about the act of allowing another person to enter your ears.

I can't speak for you, but I'm selective about who enters my ears. It's a sacred space.

That's the weird part about video podcasts on YouTube. There's nothing wrong with them, and for some, the video component is a necessary part of their media consumption choice. Yet, once a podcast is on a video screen, it's as if the podcast loses that sense of intimacy and the "I only have ears for you" quality.

Somehow, media, in its myriad formats, attaches to our daily routines in unique ways on a personal and social level. A movie theater, of course, is a social experience with moviegoers keying off the reactions of the people seated near them -- laughter, sadness, fright, and shock -- like a virus that moves from person to person, unseen but powerful.

Radio has always had a duality about it. On one hand, radio was a family experience before television when the family would sit around the Zenith Upright Radio and listen to Captain Midnight, Jack Benny, or The Shadow. In the next generation, radio was the primary source for popular rock n' roll music and was often a communal listening experience with dancing its complimentary physical activity, or perhaps a more intimate consensual contact "under the boardwalk."

Yet, radio has been slowly fenced off and restricted to commuting in a vehicle, so it's become more of a personal activity. Preset radio buttons are a touch away for us, and they are just for us.

A favorite warning when someone borrows our car.

"Do not, under any circumstances, change my radio presets."

Since its arrival in the late 40s, television has always been a communal experience, especially when a family had only one television set. Of course, sometimes only one family in a neighborhood had a TV in the early days of TV in the 50s. Back then, TV was indeed a neighborhood bonding event.

Today, streaming TV, phones and tablets that allow for TV viewing have, to a large extent, repurposed TV viewing as a more personal experience. Today, people are forever looking at their phone screens.

In a feat of technological synchronicity, the development of headphones and wireless earbuds has now walled off TV viewing from the communal to the solitary.

Even music has lost some of that pop-cultural ambiance as the current generation retreats to AirPods and its other branded cousins. Music, to a large extent, isn't in the air anymore. Just in our ears. What we listen to doesn't bring us together anymore, as much as it splits us apart.

Listening to a podcast is still a personal act. A one-person play. A deep connection between our ears and the images, ideas, thoughts, and concepts those sounds create. Photo by Mikhail Nilov

When listening to a podcast, it isn't what enters your ears that is as important as what travels from your ears to your brain.

As TV psychologist from the 1970s, Dr. Joyce Brothers, once said, "Real intimacy is only possible to the degree that we can be honest about what we are doing and feeling."

Somehow, you're never alone when listening to a podcast. The podcaster's voice isn't like the hollow camaraderie or vicious anonymity that comes from social media.

Actor Amy Poehler once said, "Find a group of people who challenge and inspire you; spend a lot of time with them, and it will change your life."

For me, those people include Stephen Dubner Freakonomics, Laur Hesse Fisher TIL Climate, Ashley Hamer Taboo Science, Seraphina Malina-Derben Seraphina Speaks, Tim Harford Cautionary Tales, Matt Gilhooly The Life Shift, Rita Richa Bippity Boppity Business, Jenn Trepeck Salad With A Side Of Fries, Shakar Vedantam Hidden Brain, and many more.

How about You?

0 notes

Text

“Focus on What’s Essential to You” - Franklin Parrasch on Making Your Own Way in the Art World

By Sarah Evers • June, 2019

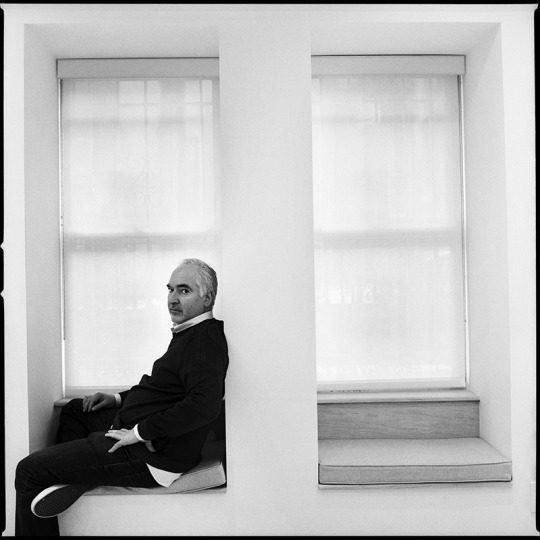

Photo by Jaiseok Kang. All images courtesy Franklin Parrasch Gallery, New York.

Walking through the Upper East Side of New York City, you may miss the unassuming façade of Franklin Parrasch Gallery. If you slow your pace to take in your surroundings and discover the gallery’s entrance, you will be rewarded by the highly cultivated exhibitions waiting inside. Located in a townhouse on 64th Street with a secluded back patio, Franklin Parrasch Gallery asks you to take the time to fully consider the work on view and how it contributes to ideas of evolution, perception, and migration.

Since his first gallery opened in the 1980s, Franklin Parrasch has maintained a dedication to furthering the careers of artists whose work defies any predetermined definitions of media or style and seeks to address existential questions through physical creation. Parrasch opened his first space in Washington, D.C. and found his passion for the intersection of art and craft, a passion that is still palpable in his curated shows in the New York City gallery. A commitment to supporting artists with distinct perspectives is fundamental to Parrasch’s role as an art dealer.

Working primarily with artists from Los Angeles while operating a business in New York City may seem an unconventional premise to some, but Parrasch makes compelling connections between the two cities through thoughtfully curated shows. In fact, Parrasch furthers this association through partnerships in both Los Angeles (Parrasch Heijnen Gallery, with Christopher Heijnen) and Beacon, New York (Parts & Labor Beacon, with Nicelle Beauchene). Whether dedicating solo exhibitions to artists he’s been representing since the 1990s or exploring hosting shows organized by galleries across the globe, Parrasch finds a way to fuse disparate ideas together in a seamless narrative.

We spoke to Parrasch to find out more about the origins of his gallery, his connections to Los Angeles, and the importance of community to his business.

Installation view of “Peter Alexander: recent work,” 2018. Photo by Adam Reich.

What inspired you to pursue a career in visual art?

I was five years old, in kindergarten in New Jersey, and my friend’s mother, who was an artist, took us to the Museum of Modern Art one day. We walked into the atrium, which was quiet and completely empty. It was just the three of us, and there were two things on the walls. One side was Guernica by Pablo Picasso, and the other side was The Dance by Henri Matisse. And that was it. Guernica, in particular, left a permanent impression on me; I was intrigued by how he combined all that imagery spatially, and fed all that information in such an exciting body of space. And I went back and drew pictures, not what other kids would do I guess, but I kind of got obsessed with that one. The intensity of both of them stayed with me—Guernica, and the poetic grace of Matisse, they all figure into what I value in art.

After I finished my undergraduate degree at Hampshire College, I worked as a color printer for various photographers, some of whom were artists, and I also worked in photo labs. When I started the gallery in Washington, D.C., I took a night shift working at another lab. I also managed the school galleries at both Hampshire College and Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), but had no prior commercial gallery work experience.

Installation view of “Everything Else,” 2008.

What led you to opening your original gallery space in Washington, D.C.?

I just happened to be there because my roommate in graduate school at RISD was from D.C., and there was a thriving art community going on in D.C. at the time. It was sort of the tail-end of the Reagan era and people were collecting. It was something to do if you had new money and there were some major collecting families in D.C. There were also some really great galleries at the time. Jack Shainman and Max Protetch both had spaces there. Martin Puryear was showing there, many artists of the Color School were working there, and it was a really active place for contemporary art. Also, of course, all the museums.

I came across an ad in the Washington Post for free gallery space in exchange for managing the building. The building of course turned out to be an hourly hotel, and I had no idea what that meant until I got there, but it worked out. I actually got a gallery running and got things to happen within that first year.

Installation view of “Please Enter, Curated by Beth Rudin DeWoody,” 2014. Photo by Katharine Overgaard.

What type of work did you show in the beginning?

While I was at RISD, I saw a graduate show of what appeared to me to be installation art. And what it was, in fact, was an installation of studio furniture by one artist. And I became fascinated by that, and I became much more fascinated in general with craft and the fine arts and how they integrate within the larger picture of contemporary art. And I decided I had to do something about that.

What inspired the move to New York?

I wanted to come back here and sort of get more connected with my roots in this area, and also to really up the ante and be involved in the arts scene here. I opened up a 4,000-square-foot space on lower Broadway in 1989 and held many memorable shows there, including our first career survey of Ken Price. The building had only galleries in it and they were relatively small, kind of a white-cube style.

The following space, on 57th Street, was where I first installed a kitchen and it became a tradition that has carried to this current space. I think it’s really important that people eat together and converse over a meal, and eat the same food and talk about it and feel on the same level. It keeps people together and closer.

Installation view of “John McCracken: red, black, blue | Painting and Sculpture, 1966-1971,” 2015. Photo by Kent Pell.

How do you see the communal meals as part of the gallery’s business model?

I’m sort of obsessed with cooking. I need to feed people, it’s something that’s sort of inherent in me. When people come to visit, I really like the fact that they enjoy the food they’re having and they enjoy sitting out at the table and talking about art and anything else that’s going on. And that affects how we socialize with our clients, and our friends, and our colleagues. It builds relationships. I would say that, for me, cooking is really integral to how we socialize.

Has your interest in craft stayed consistent through your different gallery spaces? How have you seen your interests change over time?

I’m still fascinated with the conversation of how aesthetic pleasure and efficiency tug at each other, and how there are coalesced moments. This is something that I think is inherent in everything we show. And even to the point of conceptual art, even when there’s no product at all, there’s still this element of how the mind perceives function that I’m very interested in. I also consider perception and find it to be the crux of art and evolution, which is a thread that weaves through each of our shows. Each exhibition typically has relationships to the processes of migration and evolution. Many are reckoning with the question: “Why are we here?”

I find that I’m drawn to artists from Los Angeles because the lines between craft and art there are more blurred than they are on the East Coast. I started meeting some people in L.A. and eventually realized I was very intrigued with Ken Price’s work, which I’d seen at a Whitney Biennial in the early ‘80s. I wrote him a fan letter and he invited me to come to his studio. When I got there, we just immediately connected. It was like we knew each other. We talked for an hour about his work, decided to go get lunch, and he just said to me, “I want you to be my dealer.” And I was 32 at the time. It was like a lighting bolt went off. Here I was, this kid, essentially, being asked to represent Ken Price. It was life-changing.

We of course show artists from other places—there are usually particular reasons for that—and they’re related to the thoughts and concerns we’re trying to focus on. But I find California to be this place people gravitated toward as an expression of where they could go to become themselves. And that’s what I’m intrigued by.

Installation view of “Peahead: Rita Ackermann, John Altoon, Cecily Brown, Chris Dorland, Jean Dubuffet, Jason Fox, Peter Saul, Joan Snyder, Michael Williams, and Chewa Mask,” 2014. Photo by Kent Pell.

How did this connection to Ken Price affect the gallery’s programming? Did you see any dramatic shifts?

Ken Price introduced me to his friends, who were a close-knit group of very gifted artists that included Larry Bell, Joe Goode, Ed Ruscha, Craig Kauffman, and Peter Alexander, all of whom I had an interest in and showed. This was in the early ‘90s, when things were a bit slower in the art world, and they had seen the successes that we had with Ken and they wanted to find out more about it. And that really helped direct where things evolved in the gallery. I began showing pretty steadily with Billy Al Bengston, Larry Bell, Joe Goode, and those relationships intensified. They also found other representation on the East Coast, and their careers blossomed. We did a lot to help get these Los Angeles artists established here.

But it wasn’t just Los Angeles, it was further south, like with Tony DeLap, and it was further north in the Bay Area, like with Robert Arneson. In late ‘92, soon after Arneson passed away, I visited his studio and asked his widow about a work I saw on the shelf. She told me it was a student of his, Kathy Butterly, so I sent her a note and we did a show with her soon after in 1993 and continued showing her work regularly.

Installation view of “Tony DeLap: A Career Survey, 1963-2016,” 2017. Photo by Adam Reich.

There were a lot of other events that took place in those years. I showed the models and drawings of the architect James Wines. He was the founder of the architecture firm SITE, which did very challenging, almost artistic projects. One of his biggest clients was Best & Company, which was owned by a very interesting philanthropist and collector in Virginia, Sydney Lewis, who commissioned all these buildings with falling rocks, and cars in the parking lot buried under several feet of asphalt. It looked like the building was blowing up in one case. These were really challenging buildings. I really loved the idea of function and aesthetic interests being melded. That’s kind of what I wanted to stay close to in all of this.

What differences do you find between the art worlds of New York and Los Angeles?

I think that New York has a much longer, more developed, and very tiered history, and the arts infrastructure of Los Angeles is more recently developed, and constantly changing and reinventing itself. What interests me about the art world in Los Angeles is that it’s not tied so much to any dogmatic point of view. It’s up for change, it’s up for a challenge, it’s up for morphing. I think that’s the big difference.

Installation view of “Get Outta That Spaceship and Fight Like a Man,” 2017. Photo by Adam Reich.

Can you tell us about the current show on view and what you have planned next at the gallery?

Joan Snyder, who we have represented for about six years, has often told me stories of coming out of the MFA program at Rutgers and finding this warehouse space with fellow program graduates Jackie Winsor and Keith Sonnier. I really got to thinking of what it’s like to be a 25-year-old out of graduate school and starting a practice and a studio on your own. Back then, it was so much harder because there weren’t facilities for this kind of thing. Yes, they got this building for a song, but it didn’t have electricity, it didn’t have running water and they had to pipe it in from elsewhere. But they did that. They were scrappy, youthful, and strong, and they all figured it out. And what ended up happening was they reinvented some of the basic languages of contemporary art in that space in their 20’s. It’s kind of amazing. You know, Keith did his first neons, and Joan did her first stroke paintings, and Jackie did her first rope sculptures in that building. And I felt that was just historically brilliant, and worthy of a show.

For our next show, we’re participating in Condo. Last year, we hosted Misako & Rosen from Tokyo and Gypsum Gallery in Cairo. This year, we’ll be hosting mother’s tankstation limited with locations in Dublin and London starting June 27, 2019. I’m looking forward to meeting them. We came up with an idea integrating Peter Alexander’s work, so that should be interesting.

Installation view of “Joan Snyder: Sub Rosa,” 2014. Photo by Katharine Overgaard.

In addition to the emergence of Condo as a gallery-sharing initiative, have you seen any other major shifts in the gallery business over the past decade?

I think the decade hasn’t seen that drastic of a change from my perspective because I’m not that involved with technology or social media. I’m sure that’s a big change for most people in the art world, because there’s this vast influx of interaction on that platform, but it’s been pretty much very similar for me. I see some of the trends changing, and not changing, and there’s always going to be hype that motivates a certain thing within the art world.

Do you have any advice for someone aspiring to become an art dealer?

First of all, focus on what’s essential to you as somebody who looks at art. Don’t let it be about extraneous matters, social circumstances or anything like that. Focus on what’s essential to you about art itself. And make sure it’s so essential to you that it wakes you up in the morning. Because it’ll also keep you up at night.

Installation view of “Get Outta That Spaceship and Fight Like a Man,” 2017. Photo by Adam Reich.

What would you recommend for someone starting a collection?

I think it’s really essential to find out what you want to do in your own mind. Resolve that. There’s a lot of people that collect for various different reasons, some people collect for investment purposes, some people collect for social circumstances. I encourage people to really understand, or try to understand, what quality in art means, and to understand that this process is about creating their surroundings. They’re going to be living with this material, they’re going to be looking at it, they’re going to be affected by it. What does that mean, what do they want out of that work? That should be their challenge to themselves: to really think about it and consider how it will impact them for the rest of their lives.

5 notes

·

View notes