#irmin I irmin II irmin III irmin IV

Text

kaeya is still so suspicious to me that box in a wall told us SO MUCH but also not enough. So he's not of royal blood but his first constellation is still called 'excellent blood'. the alberich clan tries to not leave any traces of it's existence. Everyone who thinks he's just 'some guy' after this is so incredibly wrong

#he's not a prince by blood#but if i understood correctly.#if no other royal survived he's next in line to be a KING????#i wonder. why exactly is the alberich clan special#and i'm surprised we got such a lore drop. IN A RANDOM FUCKING QUEST#i hope that means our yearly dainsleif quest next spring is juicy#and there's the confirmation that khaenri'ah's king is odin! cool#i wonder if it's one inmortal powerful guy (not a deity but ehh. khaenri'ah is speculated to kinda have existed. outside of linear time)#or is it a long line of kin irmins#irmin I irmin II irmin III irmin IV#are they named after the irminsul tree?#or is the tree commonly named after a king? . I MEAN. I DOUBT? just throwing ideas out there#EDIT: could also be a title that's passed down#dainsleif's title as the bough keeper also got a deeper meaning eh#i thought he's a gardener on the side but hmmm

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Red Serpent: 4. With Measured Steps

Grâce à lui, désormais à pas mesurés et d'un oeil sur, je puis découvrir les soixante-quatre pierres dispersées du cube parfait que les Frères de la BELLE du bois noir échappant à la poursuite des usurpateurs, avaient semées en route quant ils s'enfuirent du Fort blanc.

Thanks to him, from now on with measured steps and a sure eye, I am able to discover the sixty-four dispersed stones of the perfect cube that the Brothers of the BEAUTY of the black wood, escaping the pursuit of usurpers, scattered along the way while they were fleeing from the white Fort.

As in the previous stanza, the poet still draws much attention to the route he is following. From this stanza it appears that he has made good progress, as he has all of a sudden gone from desperately having to chop down vegetation to striding along with measured steps and a sure eye. The reason for this seems to be that he has begun to discover clues. The clues one needs are therefore not only hidden in the two Latin texts, but also en route in the area – which is good news at this point.

4.1 The route from Blanchefort

The poet states that he is able to see scattered stones somewhere along the way. By mentioning this, he is making sure one knows exactly which route he is following. If one fails to see any of the landmarks he reveals, it stands to reason one has no chance whatsoever of reaching the destination.

The ‘dispersed stones’ lie on the route from the ‘white Fort’ – indicating Blanchefort, as was mentioned earlier, as it literally means ‘white fort’. The question, however, is in which direction?

Fig. 10. A menhir along the route

Resorting to Boudet’s book, one discovers that he specifically mentions menhirs (upright rocks) along the road from Blanchefort: ‘At the end of Roko Négro one sees again very clearly the different foundations which served to support the menhirs, but they are overturned and dispersed here and there on the flanks of the mountain, in the greatest disorder.’[35] The poet therefore undoubtedly has in mind exactly what Boudet is referring to here.

So for the first time, one knows exactly in which direction the route goes – in that of Roque Nègre, which is also the direction in which the poet’s friend was staring. Today, this is where the footpath from Blanchefort runs, so one can simply follow it. One is therefore walking in a southerly direction, on the way to the town of Rennes-les-Bains, which lies further down at the bottom of the valley.

4.2 A flight along this route

The poet also points out that this is the way a certain group once fled along to escape ‘the pursuit of usurpers’. It was while the ‘Brothers of the BEAUTY of black wood’ were fleeing that they scattered these stones along the way.

As almost everything in the poem has absolutely no bearing on anything ordinary, this was most likely also an unusual flight. Another fact supporting this assumption is that there are old mines close to Blanchefort wherein an important treasure had allegedly been hidden earlier. The poet could therefore be referring to the time when this treasure had been fled with from the Blanchefort area. Hence, the route he is indicating is nothing less than the way along which this treasure had been transported to a new hiding place. This, in turn, would mean that the riddle embedded in the poem contains the clues as to where the treasure had been taken.

The reference to the stones along the way therefore possibly relates to this fleeing with the treasure. It could be that the stones allude to the landmarks that had been specifically placed to guide one to the new hiding place, therefore representing the directions to be followed through the area.

The poet furthermore states that the ‘dispersed stones’ form a perfect cube when put together. Each ‘stone’ therefore contains a core element of the whole, or an invaluable clue in finding one’s way. As was mentioned earlier, the inner front cover of Le serpent rouge indeed shows a person squatting, deep in thought, in front of scattered ‘dice’, with the caption: ‘Discover the sixty-four stones one by one.’

4.3 The time of Sigebert

Throughout the poem, the poet draws on different ‘layers’ of meaning. In other words, in mentioning an object, or by using an image, he more often than not refers to something related to the object or image. The escape in this stanza could therefore be connected with not only one specific escape, but a few.

There are several flights in the rich history of the region that could be relevant, some of which occurred in the distant past, and others that more specifically bear on the detail in the poem. The events in the distant past are, however, significant, as they put later events in perspective.

The earliest flight that the poet could have in mind, is that with the young Sigebert. Although this son of Dagobert II is not mentioned in earlier sources and therefore does not feature in generally accepted genealogies, his name is characteristically Merovingian; three of these kings have borne this name. However, he had been taken up as Sigebert IV in the genealogy in the document Le serpent rouge, which means the poet considers this version of history to be the truth. According to Jania MacGillivray, Sigebert is first mentioned in church records from the 16th century in the French National Library, as well as in 17th-century priestly documents of St. Vincent de Paul.

It is said that, following the murder of his father on the 23rd December, 679, in the woods close to Stenay, the three year-old Sigebert had been rescued by his half-sister Irmine, eight years his senior. A warrior (‘le Bellison’) called Mérovée Levi, a loyal subject of Dagobert II, subsequently rescued Sigebert from the clutches of Charles Martel and brought him to Rhedae. This Levi was apparently married to the sister of Bera II, the ruler of Rhedae and father of Sigebert’s mother, Gisélle. Like all the Merovingian kings, this Levi was also of Sicambrian descent.

The poet is therefore possibly referring to this flight with Sigebert from the ‘usurper’ Charles Martel. Although Charles Martel himself never went as far as dethroning the Merovingians, his son Pepin III did and subsequently became King of the Franks with support from the Catholic Church.

There seems to be evidence of the said flight with the young Sigebert to Rhedae. In the 42nd edition of the bulletin of the Le Cercle de Saint Dagobert II (June, 1996) – which I also stumbled upon during my visit to the Dagobert II Museum in Stenay – the author André Roth mentions a very old parchment that had earlier been in the possession of the monks of Orval in Belgium. After the French Revolution, the Black Sisters of the Chapel of Mary Magdalene in Mons, Belgium, placed it in the skull of Dagobert II for safekeeping. This ‘valuable parchment’ was written by Irmine, the daughter of Dagobert II and abbess of the monastery of Oeren. It tells of the rescue of her half-brother, Sigebert, who had subsequently been brought to this monastery before being taken to Rhedae, the capitol of the Razès, where he arrived on the 17th January, 681. There is also mention of the ‘Merovingian treasure’, which, according to Généalogie des rois mérovingiens, could refer to the treasure Dagobert II had sent to the Razès.

It appears that this parchment had actually been seen by several persons. On the 7th October, 1912, the bishop of Tournai’s secretary, the canon Cramme, inspected and copied it under the supervision of the Black Sisters and their head, mother Antoinette Richard. On the 31st December, 1941, the envoy of the Prince of Croy, Monsignor Delmette, visited Mons to take a photograph of the parchment as well as a part of the skull. Mother Bernadette de Haye apparently states in a letter that this parchment had later been taken by the Prince of Croy.

It is uncertain in whose keeping this parchment is today. If everything that is said about the parchment is indeed true, there can be no doubt as to the continued existence of the Merovingian bloodline. These events would then clearly be crucial in interpreting the later events in the Razès. However, like with the other parchments, one would have to wait until the experts have examined it before any valid conclusion could be drawn.

Besides this apparently invaluable document, other earlier documents also appear to refer to Sigebert, one of them being a deed of foundation dating from 718, mentioning ‘Sigebert, count of Rhedae, and his wife, Magdala’. This deed concerns the founding by Sigebert of the monastery of St. Martin of Albières. Upon an enquiry by a member of the University of Lille to the author of Le cercle d’Ulysse (who refers to this deed) about where this document could be found, the latter reportedly said it was kept in the French National Archives, but that it had not been categorised.

There is also the possibility that this deed – or another deed – relates to an incident in which Sigebert had been involved. According to the author of the document Au pays de la reine blanche (1967) (‘In the Land of the White Queen’), Sigebert and his son, Sigebert V, made a donation by means of a deed to the bishop Arbogaste as an expression of gratitude. This followed an incident at the Blésia fountain (Pontet) when Sigebert IV had been wounded in the gut during a pigsticking, upon which the bishop had come to his aid, saving his life. The abbé Pichon apparently also refers to this incident in his book Les diplômes mérovingiens.

After Sigebert IV died of a wound to the head in 758, he was buried in the crypt in the Rennes-le-Château church. The entrance to this burial chamber is said to have been covered by an engraved stone, the so-called Knight’s Stone, depicting a man and presumably a child with him on a horse. According to Les descendants Mérovingiens, this stone commemorates the flight with Sigebert to Rhedae. Saunière removed this stone. Later, a skull was reportedly discovered in the chamber, which could have been that of Sigebert.

4.4 Blésia (Pontet)

The fact that the poet refers to a flight at this point, which clearly also bears on the flight with Sigebert, could mean that he has a landmark that is connected with Sigebert in mind. The Blésia Fountain (or Pontet), where he had been wounded, indeed lies only a short distance further from Roque Nègre next to the tarred road.

The name Blésia had possibly been derived from ‘blesser’ (‘to wound’), which could also bear on the pigsticking incident. As was mentioned earlier, it may also be connected with ‘bles’ (‘gold’).

Following the footpath from Roque Nègre, it forks a short distance further on. The one path runs along the escarpment to Rennes-les-Bains, and the other down to the tarred road. If one takes the latter, one passes the Blésia Fountain on the way to Rennes-les-Bains.

4.5 The Sun King

Although the flight with the young Sigebert to Rhedae is an underlying theme in this stanza, the flight the poet is actually referring to here dates from a later period in history. This took place when one of the ‘usurpers’ – referring to the French dynasties after the Merovingians had been dethroned – apparently attempted to get his hands on the treasure of Blanchefort and the ‘Brothers’ hastily fled with it.

One of the French kings who was not only very interested in the Razès area, but evidently also in the treasure, and who sent one of his subjects searching for something that had allegedly been hidden here, was Louis XIV, the Sun King. His minister of finance, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, apparently searched and dug all over the place, among others at Blanchefort – exactly where, according to the poet, the treasure had been moved from. The fact that Colbert returned empty-handed is in keeping with the assumption that the safekeepers of the treasure had gotten away with it in time. It would therefore make sense to take a closer look at these events.

4.6 The brothers of the beauty of black wood

According to the poet, those fleeing from the ‘usurpers’ were the ‘Brothers of the BEAUTY of black wood’ – the same ones who scattered the ‘stones’ along the way. It was therefore the persons who escaped with the treasure and who were responsible for compiling the directions that future generations would need to be able to find the new hiding place.

To find out who these ‘Brothers’ are, one must obviously first determine who ‘the BEAUTY of black wood’ is. This is also not the first time the poet refers to a beauty: In the previous stanza, he mentions the residence of the sleeping beauty where he is headed.

‘[T]he BEAUTY of black wood’ may very well allude to statues made of black wood. In La vraie langue celtique, Boudet refers to such a statue of the Virgin in Marseille. It appears that this Black Virgin is connected with an alternative tradition in the Catholic Church that had been kept secret throughout the centuries. In The Cult of the Black Virgin [36], Ean Begg suggests that it represents a pagan goddess under a new banner. Some experts indeed regard the oldest madonna in the world, the Brown Virgin of the Catacomb of Priscilla in Rome, as a statue of Isis.

According to Deloux and Brétigny [37], the Black Madonna of Blois, which was honoured there up until the revolution, is the ‘eternal Isis’ honoured by the initiates of the Prieuré de Sion. To top it all, Pierre Plantard himself stated that the Black Virgin is Isis, and that she is called ‘Notre-Dame de Lumière’ (‘Our Lady of Light’).

If the ‘BEAUTY of black wood’ does indeed refer to the Black Virgin, the ‘Brothers’ who are associated with her are most probably none other than the brothers of the secret Prieuré de Sion – which is reportedly also called ‘the ship of Isis’!

Yet another very interesting fact is that the biggest enemy of Louis XIV and his first minister, cardinal Mazarin, was the secret order, the Compagnie du Saint-Sacrement (‘Order of the Holy Sacrament’). According to the authors of The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail, this group ‘conformed almost perfectly to the image of the Prieuré de Sion’ [38]. Their ‘centre of operations’ was the St. Sulpice Church in Paris. (The mother church of St. Sulpice, St.-Germain-des-Près, was apparently built on an earlier temple of Isis.)

4.7 The tombstones of Marie de Blanchefort

According to an article in the Vaincre of September 1989, some of the prominent families of the Razès were directly or indirectly involved with the Compagnie du Saint-Sacrement. This would imply that they were the ones protecting the interests of the Compagnie in the south. It is therefore quite possible that these interests relate to the ‘secret’ of the Hautpoul-Blanchefort family, and even to a treasure hidden in the area. This would mean that these families were the ones responsible for moving the treasure in the time of Louis XIV. It therefore stands to reason that they would also have been responsible for compiling the directions to the new hiding place.

Enter Marie de Blanchefort, who belonged to the mentioned families of the Razès and who figures very prominently in the Rennes-le-Château mystery. On her tombstones appeared information that one later on discovers is indispensable in decoding the hidden secret message in the second text, which most probably relates to the hiding place of the treasure mentioned in the first text. This would imply that it is the exact same treasure which Louis XIV had been after.

Unfortunately, the writing on Marie de Blanchefort’s tombstones does not exist anymore, as Saunière had deliberately removed it. However, it is said to have been published in a book by Eugène Stublein entitled Pierres gravées du Languedoc (1884) (‘Engraved stones of the Languedoc’), but of which not one single copy is apparently still in existence. In 1962, extracts from this book were apparently published under the name of abbé Joseph Courtauly. As with many of the other documents related to Le serpent rouge, the true author of this writing is most likely Pierre Plantard or Philippe de Chérisey. Exactly from where either of them would have obtained this information is not clear, but as Henry Lincoln points out in The Holy Place, at least one of these epitaphs appeared in a leaflet written by E. Tisseyre entitled Excursion du 25 juin 1905 à Rennes-le-Château (‘Excursion of the 25th June, 1905, to Rennes-le-Château).

Fig. 11. The tombstones of Marie de Blanchefort

4.8 The second Latin text

As was just mentioned, the secret message in the second text can only be deciphered with the aid of the information on Marie de Blanchefort’s tombstones. The poet also refers to this second text when stating it is thanks to the ‘manuscript’ of his friend that it is now easier to find his way.

As was also mentioned earlier, deciphering this message is an entirely different story. As it involves a highly intricate procedure, it would be virtually impossible to decode the message without the input of someone who has knowledge of this procedure. Philippe de Chérisey somehow gained access to it, but clearly did not know how to apply it. He was blissfully under the impression that the current 26-letter alphabet could be used, whereas only the old French alphabet without the w yields the correct results. The exact procedure – in all probability supplied by Pierre Plantard – can be found in an appendix to Henry Lincoln’s book The Holy Place. Lionel and Patricia Fanthorpe also provide a very clear exposition of it in their book, Secrets of Rennes-le-Chateau [39].

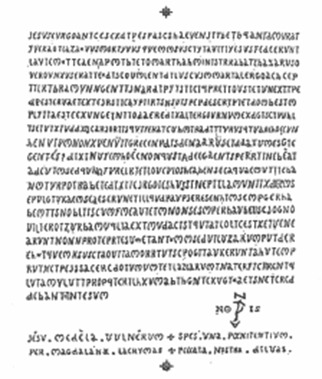

The writing in the second text is much more compact than that in the first, and the text itself is written in block-form. Close to the bottom right is a peculiar symbol with ‘NO’ and ‘IS’ written on either side, which spells ‘NOIS’ – the inverse of ‘Sion’. There is also an N above and an upside-down A beneath this symbol. Right at the bottom, separate from the main body of the text, are an additional two lines. Each of these consists of six words, all separated by either a full stop or a tiny cross. Lastly, there are two odd roselike symbols in the centre right at the top and right at the bottom of the entire text (see Figure 12).

Fig. 12. The second Latin text

Upon closer examination, one discovers that after every sixth letter in the Latin Biblical text, another letter had been inserted. There are 140 of these letters altogether, which are clearly those containing the secret message. An additional eight very tiny letters have been inserted randomly in the text. Put together, these letters spell ‘rex mundi’, which is Latin for ‘king of the world’. Contrary to the secret message in the first Latin text, which states that the mentioned treasure belongs to Dagobert II and to Sion, these words imply that the treasure ultimately belongs to the ‘king of the world’, who, according to the compiler(s), will apparently come from the Plantard family line. Over and above the Messianic connotations of these words it is therefore implied that the treasure is of such value that only the ‘king of the world’ would have a right to it.

One cannot help but wonder whether this hints at the fact that the discovery of the temple treasures of Jerusalem would play a role in confirming the kingship of such a messianic figure.

4.9 Deciphering the second secret message

Right, here we go.

The 140 letters inserted in the Biblical text are divided into two groups – 64 at the beginning and 64 at the end, with the remaining 12 in between. The number 64 immediately calls to mind the ‘sixty-four dispersed stones’ mentioned in this stanza. One later on discovers that this number is also indispensable in solving the riddle. The 12 letters in the middle are subsequently omitted from the cipher, which leaves a total of 128.

These 128 letters are then systematically transformed to other letters by means of two key phrases – which are to be found on Marie de Blanchefort’s tombstones. The first key phrase is compiled from letters on the vertical tombstone, which seem quite odd and even incorrect, namely T, M, R, O, e, e, e, p. However, when rearranged, these letters spell ‘MORT épéé’, which means ‘death, sword’ – the exact two words which the poet emphasises in the previous stanza. The second key phrase consists of all 119 letters on the vertical tombstone, as well as the letters P and S and the words ‘PRAE-CUM’ on her horizontal tombstone – which once again give a total of 128 letters.

What immediately strikes one about the first key phrase is that ‘épéé’ (‘sword’) is an unusually bad choice for a codeword. As Ted Cranshaw put it in his article: ‘Of all possible four-letter keywords in the French language, épéé is the worst.’ However, it may very well be that the person who had devised the code had deliberately chosen this very word due to its symbolic meaning. As was mentioned earlier, one edition of the Circuit also has a sword on the cover (see Figure 6). The emphasis on a sword could allude to revenge – a theme that recurs later on in the poem when the poet describes the red serpent as ‘red with anger’. This serves as one more reason that it is highly unlikely that the person responsible for the encoding had gone about it just for fun.

Now for the mentioned transformation. In the first step of the procedure, the key phrase ‘MORT épéé’ is written repeatedly above all 128 letters. The numerical value of each letter in the 25-letter alphabet is what is crucial here: a = l, c= 3, e = 5, and so on. The numerical values of each of the two letters on top of each other are then added to yield the numerical value of a third letter, e.g. 1 + 19 = 20. (As the relevant alphabet only consists of 25 letters, 26 is again regarded as 1.) On completion, one then has a new series of 128 letters that correspond to these acquired values.

This procedure is repeated with the second key phrase, namely the 128 letters on both Marie de Blanchefort’s tombstones. These letters are now written above the acquired 128 letters for a further transformation, but this time the key is written backwards – in other words, the last letter is written first, the second last letter second, and so on. The numerical values of each of the two letters on top of each other are then, once again, added to finally yield a new series of 128 letters.

For the final step in the decoding, one needs two chess-boards. Just as 64 represents the number of blocks in a cube (as the poet states), there are 64 blocks on a chess-board (8 x 8). This is why the numbers 64, as well as 128 (64 x 2), are so significant.

The 128 letters acquired by means of the transformations are now unpacked on the blocks of the two chess-boards. Next, a closed knight’s tour (see Figure 13) is used to at last unravel the secret message. This knight’s tour entails the letters being taken out one after the other according to the moves of a knight on the board. When the knight has landed on every single block, the tour is completed.

Having performed the knight’s tour on both chess-boards, one should finally have the deciphered message!

This specific knight’s tour, devised by the skilled Swiss mathematician Leonhard Paul Euler, reveals a striking geometrical pattern, in which a shape partly resembling a pentagram and partly a hexagram becomes visible. Besides the fact that the hexagram is highlighted in the poem, it also appears on the Hautpoul-Blanchefort coat of arms.

Fig. 13. The knight's tour to be used

The hidden secret message in the second Latin text reads:

‘BERGERE PAS DE TENTATION QUE POUSSIN TENIERS GARDENT LA CLEF PAX DCLXXXI PAR LA CROIX ET CE CHEVAL DE DIEU J’ACHEVE CE DAEMON DE GARDIEN A MIDI POMMES BLEUES.’

This could be translated as: ‘SHEPHERDESS NO TEMPTATION THAT POUSSIN TENIERS HOLD THE KEY PEACE 681 BY THE CROSS AND THIS HORSE OF GOD I COMPLETE THIS DEMON GUARDIAN AT MIDDAY BLUE APPLES.’

There is, however, one more thing: The fact that a geometrical pattern is to be drawn according to certain pointers in the first text, leads one to suspect the same holds true for this one. Upon closer examination, it soon becomes clear that some kind of pattern has indeed been hidden in the text: If one connects the roselike symbols at the top and bottom of the text, then produces another line through the two tiny crosses in the two separate lines at the bottom, these two lines intersect more or less in the centre of the parchment.

The implications of these geometrical patterns are as yet an enigma, but progressing on the route, one discovers how brilliantly and ingeniously they have been devised.

35. Boudet, H. 1886. La vraie langue celtique ... Carcassonne. Reissue: 1984. Belisane: Nice, p. 231.

36. Begg, E. 1985. London: Arkana,

37. Deloux, J. & Brétigny, J. 1982. Rennes-le-Château. Capitale secrète de I’histoire de France. Paris: Editions Atlas.

38. Baigent, M., Leigh, R. & Lincoln, H. 1982. London: Jonathan Cape, p. 183.

39. Fanthorpe, L. & P. 1992. York Beach: Samuel Weiser.

1 note

·

View note