#interregnum clergy

Text

I'm pleased with this recent review by John Reeks in the English Historical Review of my edited collection

Church and People in Interregnum Britain (London: University of London Press, 2021)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

September 26th 1290 saw the death of Margaret "Maid of Norway" Eiriksdottir, and uncrowned Queen of Scotland, on Orkney.

Margaret was the last of the line of Scottish "rulers" descended from King Malcolm III Canmore. Margaret's father was Eric II, king of Norway; her mother, Margaret, a daughter of King Alexander III, who you will all know, took a tumble off a cliff near Kinghorn four years beforehand. Because Margarets uncles, Alexander and David had died before reaching adulthood, the Scottish lords proclaimed the infant Margaret as their queen.

The young queen's great-uncle, King Edward I of England, arranged a marriage between Margaret and his son Edward, later King Edward II of England, a sort conquering by stealth. On the voyage from Norway to England, however, Margaret fell ill and died. The death of Margaret left Scotland without a Monarch and at the mercy of Edward I. Although the marriage treaty had specified that Scotland was to maintain its independence of England, Edward now proclaimed himself overlord of Scotland; the Scots resisted, and for more than 20 years Scotland suffered foreign domination and civil war. Thus begun the first Interregnum, and the contest between 13 claimants.

The voyage is possibly alluded to in the ballad Sir Patrick Spens. With her death, the House of Dunkeld came to an end. Her corpse was taken to Bergen and buried in Christ's Kirk at Bergen, beside her mother, who tragically died giving birth to Margaret.

In Norway, this was not the end of Margaret's story. In 1300, one year after the death of King Eirik, a woman arrived at Bergen, claiming to be the Princess, and accusing several people of treason. The city people and some of the clergy supported her claim, in spite of the late King Eirik's identification of his dead daughter's body, and the fact that the woman appeared to be about 40 years old. "The false Margaret" and her husband were convicted for fraud: he was beheaded and she was burnt at the stake in 1301. The story of the betrayed Princess was spread through a popular ballad, and a local martyr cult occurred in connection with a small St. Margaret Church near the place of the execution.

The pic shows Lerwick Town Hall's stained glass window depicting "Margaret, queen of Scotland and daughter of Norway"

Read the Ballad Of St Patrick Spens and translation here https://www.encyclopedia.com/.../edu.../sir-patrick-spens...

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Józef Poniatowski’s family album.

Part II. Grandparents, uncles, cousins (or 3 Stanisławs, 2 Konstncjas, Kazimierz and Michał )))

This week let’s continue talking about prince Józef relatives. In the previous post on the topic I wrote (and showed portraits) of Pepi’s parents and sister. So today there will be images and some information about others.

Let’s start with the grandparents. (Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to find much about Poniatowski’s maternal ancestors, so this post will be about relatives from his father's side...)

This fancy gentleman is the father of prince Anrdzej and the progenitor of the family - Stanisław Poniatowski.

Portrait of Stanisław Poniatowski, unknown painter, 18th century

He was born in 1676, as a son of a petty nobleman from Lesser Poland. And died in 1762, having achieved the highest rank possible for a civil servants in the Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth - the castellan of Kraków. (Speaking in modern terms Stanisław Poniatowski can be called a self-made man.)

Of course, the life of such a man was full of ups and downs. That is why telling you about him I would like to focus only on things, which IMHO had some similarities with the destiny of Stanisłasw’s grandson, prince Józef.

During the Great Northern War Stanisław took the side of the Swedish king Charles XII and the latter’s protégé - as a king of Poland - Stanisław Leszczyński. (On the other side there were Peter The First of Russia and August II of Saxony, who had been elected as a Polish king.)

To the misfortune of the first party, one of the decisive battles of that war, the one Poltava in 1709, was lost, but this wasn’t a reason for Poniatowski to turn his back on Charles. On the contrary, Stanisław then saved life of his suzerain, and after that help him to flee to Turkey. And remained faithful the Swedidh king to the very end, till Charles’ death 10 years later. (Although for this reason Stanisław had to spend all these years abroad, taking care of various matters of the latter.)

Marcello Bacciarelli, Portrait of Stanisław Poniatowski, after 1758, National Museum in Warsaw

And only after Charles passing away, Poniatowski went to Poland and asked pardon from August II. And having received it, remaining a faithful servant of that ruler till the Saxon king’s death in 1732.

During the next interregnum, however, Stanisław supported again the candidacy of Stanisław Leszczyński, the former protégé of Charles II. And only under the pressure of circumstances (one of his youngest sons, his namesake Stanisław, the future last king of Poland, was kidnapped by the adversaries of the opposite, Saxon party, to forced Poniatowski to join them) he switched sides.

As for Stanisław’s private life - it was also not without complications. In 1710 he married Teresa Jasieniecka, a widow of a Lithuanian nobleman Ogiński. But shortly the wedding it turned out that Teresa’s financial state was not so well as expected, instead of money she possessed debts only. And it looks like it was the reason for Poniatowski to leave her. (Some sources even say that the couple eventually divorced).

Anyway, whatever happened with Teresa later, in 1720 Stanisław seemed to be eligible again, because that very year he married again, this time to Konstancja Czartoryska.

Per Krafft the Elder: Portrait of Konstancja Czartoryska, circa 1768, National Museum Kraków

Being born circa 1700 Konstancja was about 20-25 years younger than Stanisław’s, but this didn’t prevent the the marriage from being successful. The reason might have been that, though for Poniatowski this was again a kinda “strategic marriage” (because the Czartoryski family was very powerful), the bride was really in love with her groom. To such an extent that she married him despite her father’s will.

Marcello Bacciarelli, Portrait of Konstancja Czartoryska, 18th century

And, in general, Konstancja was so stubborn and willful, that in the family she was called “Chmura gradowa” (hail cloud).

As an example of her adherence to principles there might be recalled the story of her son Kazimierz duel with Adam Tarło. First she forced Kazimierz to challenge Tarło - though even by the standards of that time the reason doesn’t seem justified enough. An then, when the shooting happened with no harm to both sides and young men reconciled, the mother made the son to challenge his former adversary twice. And that time the duel ended with a death, fortunately to her - not of her son.

And such a story was not a unique one. (And something prompts me that had Konstancja been alive in 1761, when her son Andrzej, prince Józef’s future father, was about to marry a Czech noblewoman Teresa Kinska, the princess Poniatowska might not have agreed to that union. But the latter died already in 1758, so it wasn’t hard for Andrzej to get agreement from his very old and ailing father...)

Now, let us move to the next generation of Poniatowskis. The most known of them (and who, btw, was the favorite son of his mother) is Stanisław Antoni. Because in 1763 he was elected to become the king of the Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth (and, ascending the throne, changed his second name to “August”).

Johann Baptist von Lampi the Elder: Portrait of Stanislaus Augustus in a dressing-gown, between 1788 and 1789, National Museum in Warsaw

Do you remember that the second name of prince Józef was “Antoni”? Yes, he got it in honor of that uncle of his!

And later Stanisław August had a lot of influence on his nephew, taking care on young Pepi and his older sister Teresa after their father’s death in 1773.

But in my opinion it won’t be correct to call prince Józef the favorite of king Stanisław, the person whom the latter saw as his possible successor on the Polish throne. Why? Because there also was the oldest of Stanisław’s siblings children, the son of the above mentioned Kazimierz and the king’s namesake - one more Stanisław. (More about him - a little bit below.) And only for the short period from 1791, when that Stanisław withdrew from public life and emigrated to Italy, till 1795 Pepi’s candidature might have seriously been seemed as a possible royal successor.

Ok, now let’s look at Kazimierz. In addition to participating in that infamous duel the oldest of survived sons of the Poniatowskis was known for leading a rather riotous life. Having married a wealthy bride Apolonia Ustrzycka he had a lot of money and spent them freely and sometimes rather eccentrically. In his greenhouses, for example, there were grown... pineapples! And he also brought to Poland from Africa a bunch of monkeys (though all they died shortly because of the cold Polish climate (( )

Unidentified painter, Portrait of Kazimierz Poniatowski, second half of 18th century, Palace Museum in Wilanów

In his private life prince Kazimierz was also a real child of his time - he had several mistresses. And one of them he even drove around Warsaw naked - so that everyone could "see" her charms. (You see, prince Józef had people among his uncles to take examples from ))) And I must also mention, that Kazimierz had a loving affection for his nephew. And in the last decade of the 18th century, when Pepi was already living in Warsaw, the uncle willingly invited the nephew to his place and even supported him financially.

And despite that notorious style of life prince Kazimierz outlived all his younger brothers and died in 1800, being almost 80 years old.

And now a little bit information about Michał, the youngest of prince Józef uncles. He was destined by his parents for the clergy, and in the church hierarchy he “climbed” to the highest Polish rank - the Primate of Poland. (Though, as many sources state, prince Michal was a priest just in the spirit of his age - having mistresses and possible even illegitimate children.)

Marcello Bacciarelli, Portret of Michał Jerzy Poniatowski, National Museum in Poznań, 18th century

And the circumstances of his death in 1794, in the age of 57 years only, still aren’t clear enough. That was the time, as you may remember, of Kościuszko’s Uprising, and Michał was among supporters of the king and the latter’s pro-Russian politics. So, when the primate became seriosly ill and then died there appeared rumors, that that might have been a suicide, in fear for being hanged, as those members of Targowica Confederation who weren’t lucky to flee.

In relation with prince Józef I can name only one significant thing of Michał’s biography - it was who from him Pepi inherited Jabłonna village under Warsaw with its famous palace.

For the record I should also mention that the Poniatowskis-senior had also 2 daughters, Ludwika Maria and Izabela, but they didn’t seem to play significant roles in their nephew’s life.

And now let’s look at the third generation - Pepi’s cousins, children of prince Kazimierz.

This is the very prince Stanisław, whom I mentioned above:

Angelica Kauffman, Portrait of Stanisław Poniatowski (1754-1833), 1786

Very well educated and economically talented, he carried out a lot of reforms in his vast estates in Ukraine, and made these land prosper. Being interested in art, he founded a painting school in Warsaw. More than once a member of the Sejm, elected marshal of the knighthood of the Permanent Council, member of the confederation of the Four-Year Sejm and... not a popular figure among the the nobility (szlachta).

Because of the latter reason in 1790 there arose a conflict between prince Stanisław and his adversaries, after which the prince resigned from all his post and abroad.

Portrait of Stanisław Poniatowski (1754–1833), attributed to Johann Baptist von Lampi the Elder, 18th century

He settled in Italy, where he owned estates, and unlike his cousin Józef, never returned to public life.

As for Stanisław’s private life - well, it also looked like a suitable plot for a romance novel. The prince met his future wife in Rome, when he was already in his fifties. She was thirty years younger than him and... a wife of his neighbor.

Her name was Cassandra Luci, and she was a common woman, beaten by her cruel husband. And one day, trying escape from an attack, she knocked on prince Poniatowski’s door, was allowed to enter his residence, and stayed with the latter forever.

First, of course, Cassandra served in Stanisław’s residence just as servant, becoming the housekeeper. But soon she answered his feelings, and... by 1816 the couple had already 5 children - 2 sons and 3 daughters. And when in 1830 Cassandra’s husband died, Stanisław was finally able to marry her.

And all the Poniatowskis living now in France are descendants of this couple. Or, to be more precise, of their second son Joseph Michael.

Relating to prince Józef - it looks like his cousin Stanisław didn’t have much affection on him. They met a couple of times before Pepi moved to Warsaw in 1788, definitely had chances to see each other between that time and the year when Stanisław emigrated, but that’s all. And much more close prince Józef was with his other “probably” cousins - the sons of king’s mistress, Elżbieta Grabowska. (But this definitely goes out the topic of this post.)

So, let’s move to the last person of today’s article, prince Stanisław’s younger sister princess Konstancja.

Marcello Bacciarelli, Portrait of Konstancja Tyszkiewicz, nee princess Poniatowska, circa 1775

And, I have to admit, she didn’t play any significant role in Pepi’s life either. (Though her daughter, Anetka, might have had - but about the latter I will write later, when the time comes to publish next post of prince Józef women.) But the reason I am writing about this Konstancja now is that her husband’s surname was Tyszkiewicz, just like the surname of the Pepi’s sister Teresa’s husband.

If you ask me whether those two Tyszkiewiczs were relative, I would answer you that they were very distant ones, because last common ancestor was the progenitor of the Tyszkiewicz family, named Tyszka, who lived in the 15th century.

As for why the king decided to marry both his nieces to the Tyszkiewicz family - on this question I don’t either have an answer. But I can quote you a verse which was written in Poland that time:

Tyszkiewicza

Król policzą

Między bliskich swoje

Dał jednemu

Dał drugiemu

Swych synowic dwoje

(Translation: The king counts the Tyszkiewiczs among his relatives, he gave to one of them and to another two of his nieces)

And because of these two Tyszkiewiczs, and the fact that Anetka Potocka née Tyszkiewicz is sometimes called prince Józef’s niece (though in fact they were first cousins once removed) Teresa Poniatowska, Pepi’s sister is, in these cases, called her mother, which is not at all true. And eery time I write such a statement it that makes me cringe. That is why I felt I ought to write about Konstancja, for the people know that there was one more Mrs. Tyszkiewicz, and that she was Anetka’s real mother.

Well, that’s all for today. and I hope I didn’t make you much tires with untangling all these family ties? ))

#józef poniatowski#the poniatowskis#poniatowski#stanisław poniatowski#stanisław august poniatowski#polish history#konstancja poniatowska#kazimierz poniatowski#michał poniatowski

6 notes

·

View notes

Quote

The Book of Common Prayer was now banned, but this rule was scantly enforced. Only a quarter of the serving parish clergy were ever expelled. Many of the rest continued using the old service book, either wholesale or by tweaking it to minimize offence. Some of the former bishops, deprived of their offices, were allowed to remain at liberty, and these men ordained clergy at a prodigious rate. Although these ordinations were outlawed, their numbers fell by less than half from the late 1630s to the late 1640s. More young ministers in the 1640s or 1650s were illegally ordained by a bishop than were legally ordained by a presbytery. A few pragmatic souls had themselves ordained by both. […] The result was a new environment that changed Prayer Book religion profoundly. Freed from the constraints of legal uniformity and of active oversight from bishops, these believers began to experiment with their traditional religion in untraditional ways.

Alec Ryrie on continued Anglican life. Protestants, pp.129f.

A corrective to Christopher Hill’s more dismissive appraisal of Anglicanism during the interregnum. Ryrie and Hill are not as far apart as they may at first appear, though: while Hill overlooks the continuation of Anglican life at a parish level, Ryrie observes (as we see above) that this was the emergence of Anglicanism in a “sectarian” sense (“by far the largest of all the Protestant sects to emerge from this period”), as distinct from the Church of England as a “national” faith.

0 notes

Text

Chaos and Order at Staunton Harold church, Leicestershire

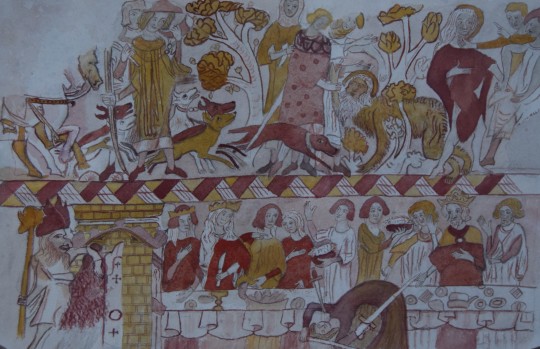

Our choir at Portsmouth are performing Haydn's Creation this weekend, with its fabulous depiction of chaos and light, so it was interesting to see what seems such an eighteenth century concept represented nearly 150 years earlier at Staunton Harold Church in Leicestershire. This is a rare example of a church built during the interregnum, and a Laudian one at that, at a time when what we know of today as Anglican worship, with the Book of Common Prayer and its formal style of dress and worship, was outlawed.

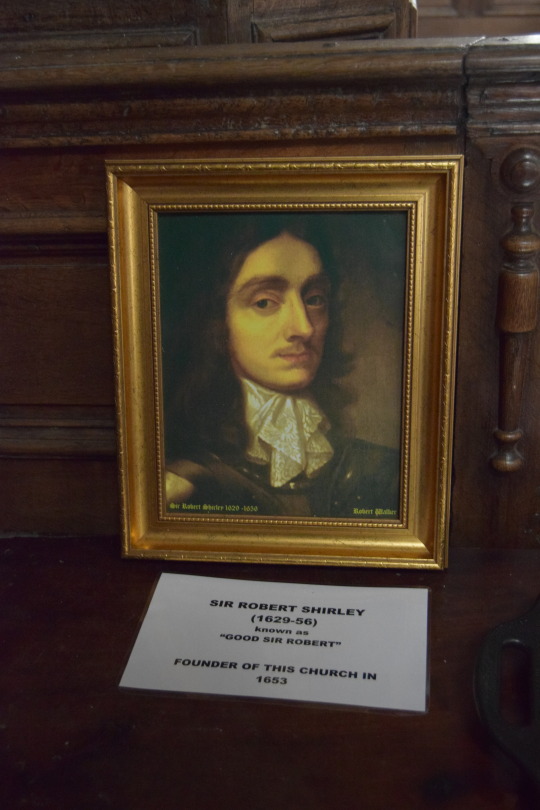

The church was commissioned by royalist activist Sir Robert Shirley, who died of smallpox in the Tower of London in 1656. Shirley was too young to have fought in the civil wars of the 1640s, but an example of a new royalist, ardently loyal to the banned rituals of the Church of England.

Reproduction in the church of a painting of Sir Robert by Robert Walker - it is not clear where the original resides. Evidently he was a handsome fellow, and managed to produce five children before his untimely death.

Yet his design, while Laudian in its inclusion of a high altar, contains little else to offend puritan sensibilities. It is plain in style, its only significant imagery on the ceiling being sufficiently abstract to avoid contravening parliamentary ordinances against superstitious images. It compares and contrasts chaos (including a black dog said to represent Cromwell) on the left and order on the right, including the word for God in Hebrew and Greek.

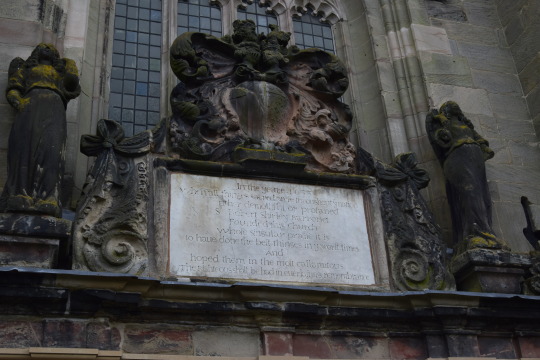

The design was completed after Shirley's death and Archbishop Gilbert Sheldon, a beneficiary of Shirley's will, erected this plaque at the entrance to the church, praising Shirley for doing the 'best things in the worst times' by building the church, as well as supporting 'distressed and orthodox' clergy who had lost their livings for refusing to support the puritan changes to the church.

#Sir Robert Shirley#Staunton Harold Church#Leicestershire churches#Laudian churches#Gilbert Sheldon#Royalism#English Civil Wars

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

September 26th 1290 saw the death of Margaret "Maid of Norway" Eiriksdottir, and uncrowned Queen of Scotland, on Orkney.

Margaret was the last of the line of Scottish "rulers" descended from King Malcolm III Canmore. Margaret's father was Eric II, king of Norway; her mother, Margaret, a daughter of King Alexander III, who you will all know, took a tumble off a cliff near Kinghorn four years beforehand.

Because Margarets uncles, Alexander and David had died before reaching adulthood, the Scottish lords proclaimed the infant Margaret as their queen.

The young queen's great-uncle, King Edward I of England, arranged a marriage between Margaret and his son Edward, later King Edward II of England, a sort conquering by stealth. On the voyage from Norway to England, however, Margaret fell ill and died. The death of Margaret left Scotland without a Monarch and at the mercy of Edward I. Although the marriage treaty had specified that Scotland was to maintain its independence of England, Edward now proclaimed himself overlord of Scotland; the Scots resisted, and for more than 20 years Scotland suffered foreign domination and civil war. Thus begun the first Interregnum, and the contest between 13 claimants.

The voyage is possibly alluded to in the ballad Sir Patrick Spens. With her death, the House of Dunkeld came to an end. Her corpse was taken to Bergen and buried in Christ's Kirk at Bergen, beside her mother, who tragically died giving birth to Margaret.

In Norway, this was not the end of Margaret's story. In 1300, one year after the death of King Eirik, a woman arrived at Bergen, claiming to be the Princess, and accusing several people of treason. The city people and some of the clergy supported her claim, in spite of the late King Eirik's identification of his dead daughter's body, and the fact that the woman appeared to be about 40 years old. "The false Margaret" and her husband were convicted for fraud: he was beheaded and she was burnt at the stake in 1301. The story of the betrayed Princess was spread through a popular ballad, and a local martyr cult occurred in connection with a small St. Margaret Church near the place of the execution.

The pic shows Lerwick Town Hall's stained glass window depicting "Margaret, queen of Scotland and daughter of Norway"

Read the Ballad Of St Patrick Spens and translation here https://www.encyclopedia.com/arts/educational-magazines/sir-patrick-spens#A

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Freakonomics and interregnum first names

The puritan period is famous for unusual puritan first names, but these were perhaps less common than the legend.

In 2013 I worked out the top 10 names for clergy in my database of Matthew Parker’s 1561 clerical survey, finding that nearly half were called either John (23%) followed by Thomas (13%) and William (13%)

https://fionamccall.tumblr.com/post/58505321728/freakanomics-and-elizabeth-is-clergy

I’ve since been working on people involved with religious offences in the secular courts during the interregnum and to date have over 10,000 people’s names in the database. It should be noted that these include people of all social classes, not just clergy, unlike the Parker survey. The top five men’s names appearing in this database are, as before and in the same order, John, Thomas, William, Richard and Robert. Edward had overtaken Henry by some measure, although perhaps this good Saxon name was more popular in the general population; he was after all an English saint. George and Nicholas remain in the same position at no. 8 and no 10 respectively. No surprise that James had moved into the top ten at no. 9 but not Charles, which was not even in the top 20.

The only puritan man’s name I could find was Gratious – as these were often people getting into trouble with the puritan regime, perhaps that’s no surprise. There was however a good sprinkling of biblical and Roman names including one Zorababell and one Policarpes. In Yorkshire there are one or two individuals named Easter but no Christmas!

The top ten womens’ names include Elizabeth and Mary neck and neck at the top of the list. As is the case even today, girls’ names were more widely distributed. Puritan names used for girls tended to be the ones we still use today, including thirteen Graces, three Prudences, one Constance, one Honor, one Faith and one Charity (but no Hope!). Partly I think relates to the practice of female personification of the virtues, which predates the puritan period. There were also six Christians (only one male), three Clement or Clemences (seven male, three female), two Comforts and one Embrace.

Top 10 men’s names in my interregnum database at May 2020

1 John

2 Thomas

3 William

4 Richard

5 Robert

6 Edward

7 Henry

8 George

9 James

10 Nicholas

Top 10 Women’s name in my interregnum database May 2020

1 Elizabeth

2 Mary (incl. Marie, Maria)

3 Anne (incl. Ann, Anna)

4 Margaret

5 Joane

6 Jane

7 Alice

8 Ellen

9 Katherine (several variants)

10 = Dorothy and Susan (incl. Susana)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Nothing funnier than a young saint

This week The Week featured a quote from Aphra Behn ‘ “There is no sinner like a young saint.” Behn was a teenager during the interregnum, so she had probably seen plenty of the species. I’m currently re-reading the diary of Philip Henry, minister at Worthenbury on the Welsh borders during those times. Although Henry’s father was a royal servant, and Henry himself witnessed and condemned the execution of Charles I, in his religious beliefs Henry had all the enthusiasm of a born-again puritan convert. In his earnestness to do well, Henry worries incessantly as to the appropriateness of his own thoughts and behaviour, to an extent that can seem somewhat comical, looked at from the distance of time particularly, as quite often happens, his plans for sufficient ‘seals’ on his ministry don’t always work in proportion to the effort put in to trying to secure them. Henry’s birthday was somewhat appropriately 24th August, since he was one of the ‘Black Bartholomew’s’ day ministers who were ejected for refusing to comply with the Act of conformity of 1662, which came into force on that day. Five years before that, in 1657, he adds celebrating his birthday to the long list of inappropriate behaviour for a Godly minister:

Aug. 24. This day compleats my Age of twenty six yeares; I have been so long in the world & yet how little can I shew of service done for God; o what cause have I to bee ashamed. Note. The Scripture mentions but two that I know of that observ’d their Birth-day with feasting & they were both wicked men, Pharaoh, Gen. 40.20 & Herod Math. 14.6. I doe not so observe it, but rather as a day of mourning.

Source: The Diaries and Letters of Philip Henry, ed. M.H. Lee (1882), p. 58.

0 notes

Text

A Hampshire Werewolf

Some more wall paintings, this time from the St Hubert’s church, Idsworth, on the Hampshire-Sussex border. They are a little faded, but helpfully the church has a picture indicating what they would have looked like originally.

Check out Salome doing what passed for sexy dancing in the 14th century!

The subject matter is unusual: St Hubert is shown curing a lycanthrope or werewolf.

Interesting, a later addition is this text next to the pulpit.

A helpful translation is provided: ‘Cry aloud, spare not, lift up thy voice like a trumpet, and declare unto my people their transgression, and to the house of Jacob their sins - Isaiah 58:1. Clearly this was one preacher who didn’t mind making his congregation feel uncomfortable, as puritans were wont to do - it didn’t always make them popular! No date is indicated for the text. The list of incumbents in the church lists George Tillingham as ejected (actually Gillingham according to the Clergy of the Church of England Database and A.G. Mathews, Walker Revised, who gives J. Audley as the interregnum intruder). The church was part of the parish of Chalton, but in the interregnum parishioners had their goods distrained for not paying church rates, claiming they were a distinct church. There must have been a few more of them around in those days. These days the church is very isolated (I drove round it twice before I found it) and a great place for a long walk, on a hill, surrounded by sweeping fields, conservation areas and wooded hills in the distance.

The church has a bit of everything, also features a a saxon light, a medieval font, a 17th century pulpit (all Hampshire church pulpits seem to be Jacobean and quite a few fonts ancient) and box pews. Comfortable ones like these for the more important people; benches for the rest.

0 notes

Text

A jack of all trades

Walker correspondents love to cite the unlikely previous careers of the interloping interregnum clergy. John Kemble described Thomas Harison of Charlton Kings in Gloucestershire as:

a man of no learning but all spirit, never in orders, a profest Anabaptist, he had been, a mercer, a stationer a schoolmaster, a dairyman, then a souldier .., at last a preacher.

Bodleian Library, MS J. Walker, C7, fo. 141

But as Annabel Gregory comments in Rye Spirits (2013) multiple talents were sometimes necessary to make a living in more marginal areas like the Weald of Sussex. A man known as the ‘Archimedes of Wadhurst’, according to an entry in the parish register, was

by trade a glover, a joiner, a carpenter, an instrument maker, a curious workman for jacks, clocks, pieces, stoves and vices for glaziers

At least he didn’t try to preach as well.

0 notes