#international working women's day

Text

March 8th: International Women's Day

The Palestinian woman: the guardian of the dream and the shield of the revolution

(Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, 2024)

#pflp#popular front for the liberation of palestine#march 8th#international working women's day#international women's day#free palestine#palestine#feminism#women#guerrilla#communism#revolution#poster#propaganda#posters#2024

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

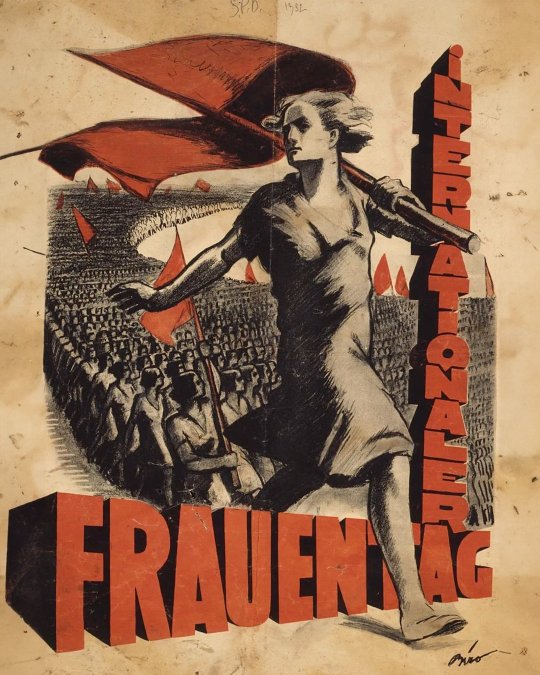

International Working Women's Day 2024

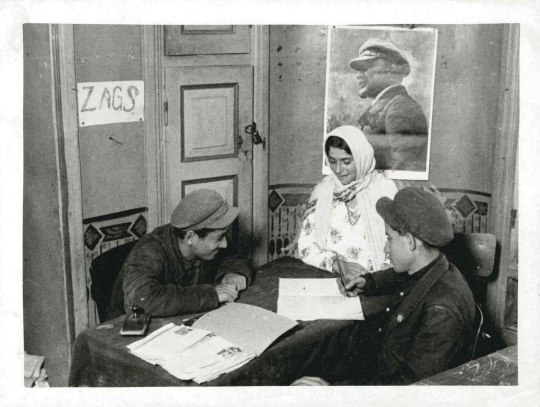

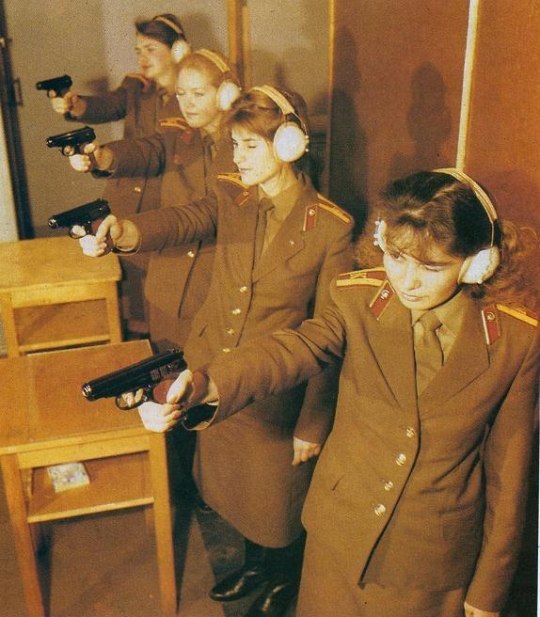

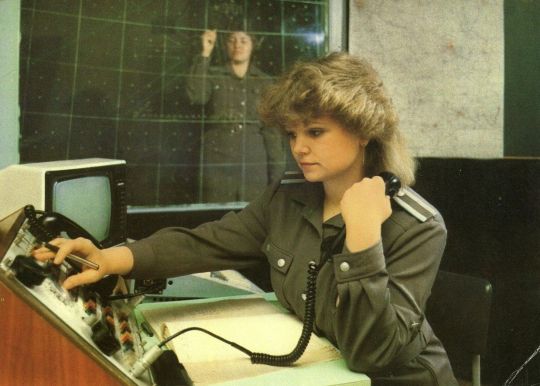

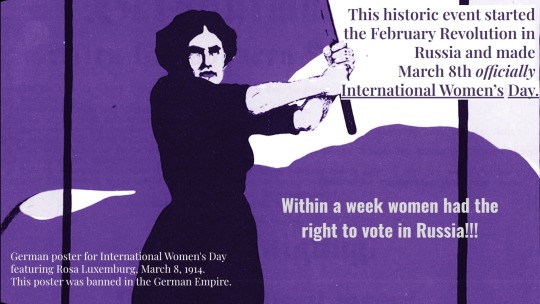

The first Working Women's Day in 1917, which marked the beginning of the February revolution and was declared a national holiday in the Soviet Union the same year, thanks to comrades like Clara Zetkin and Alexandra Kollontai. It remained a communist holiday until its adoption in the 70s by the UN, of course, dropping the "working" part in the name of the holiday.

462 notes

·

View notes

Text

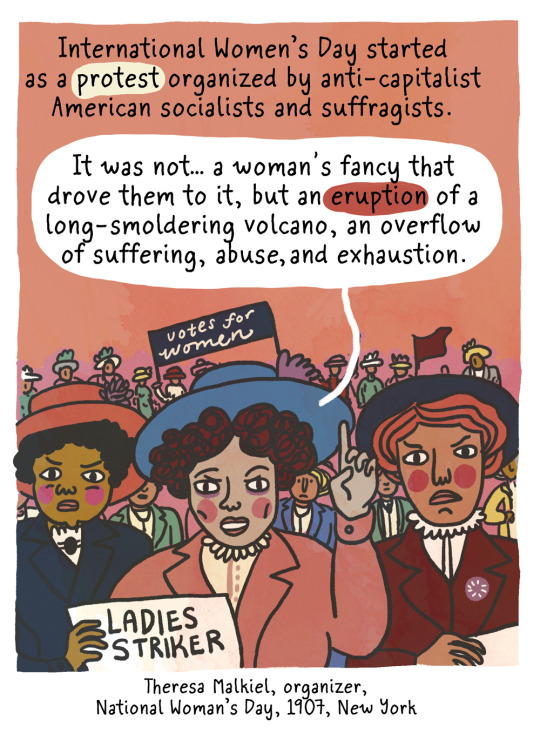

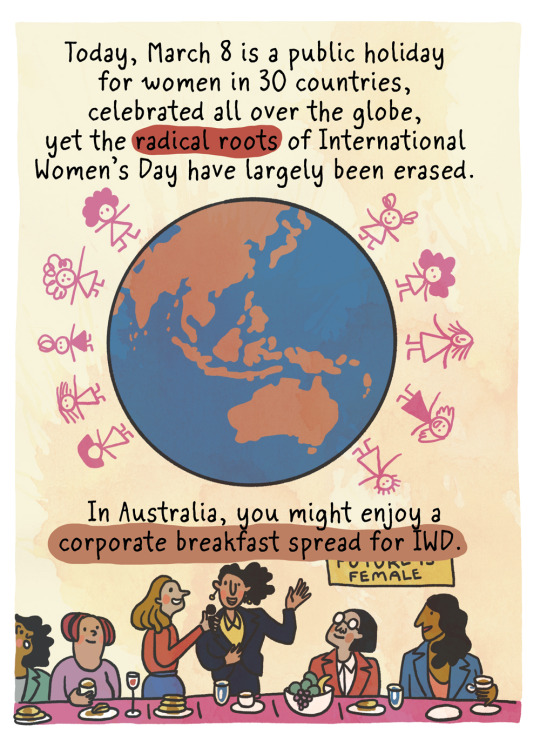

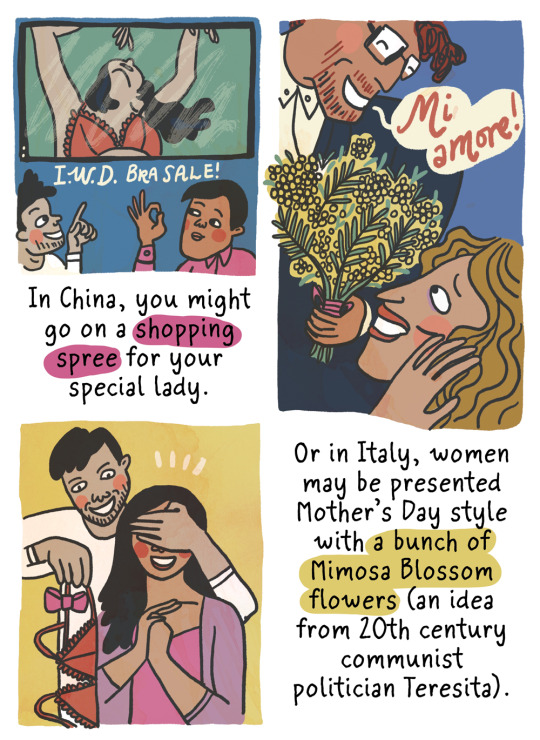

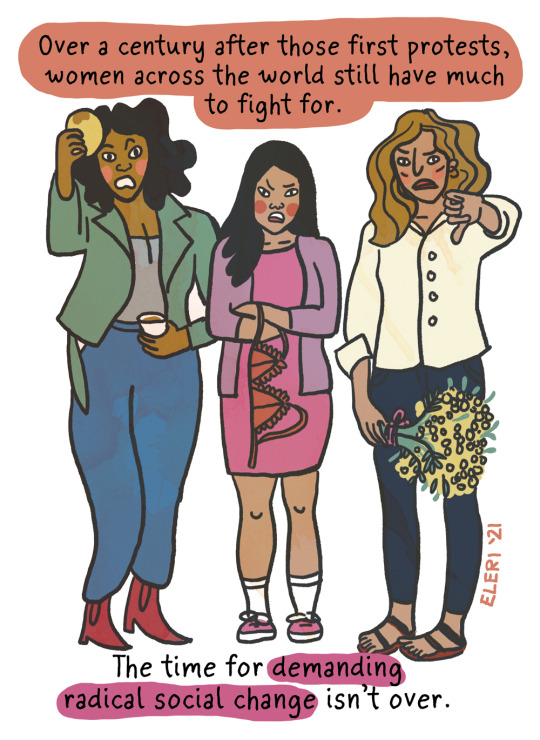

I wanted to share this informative little comic for International (Working) Women's Day:

#international working women's day#international women's day#eleri harris#herstory#worker's rights#herstory blogging#lesfem blogging#women's art#i couldn't find any good posts in a brief tag search.. apparently must do everything myself on women's day smh#i hate seeing lame corporate meaningless soundbytes when this is actually us working women's labor rights day#some of the dates in the comic may be a bit off... will have to check again later

828 notes

·

View notes

Text

the iwd presentation I made for my school

#international women's day#international working women's day#women's day#socialism#women's history month#mine

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

AlterMidya on Twitter @altermidya:

PANOORIN: Nagsama-sama ang iba't ibang organisasyon para sa #IWWD2024. Tampok na usapin ang paglaban sa niraratsadang Charter change ng Marcos Jr administration.

2024 Mar. 8

Philippine Collegian, official student publication of UP Diliman, on Twitter @phkule:

NOW: Multisectoral groups march from Vicente Cruz Street to Mendiola to register their calls for wage increase, genuine agrarian reform, and national sovereignty this International Women’s Day.

#IWWD2024 #AbanteBabae

2024 Mar. 8

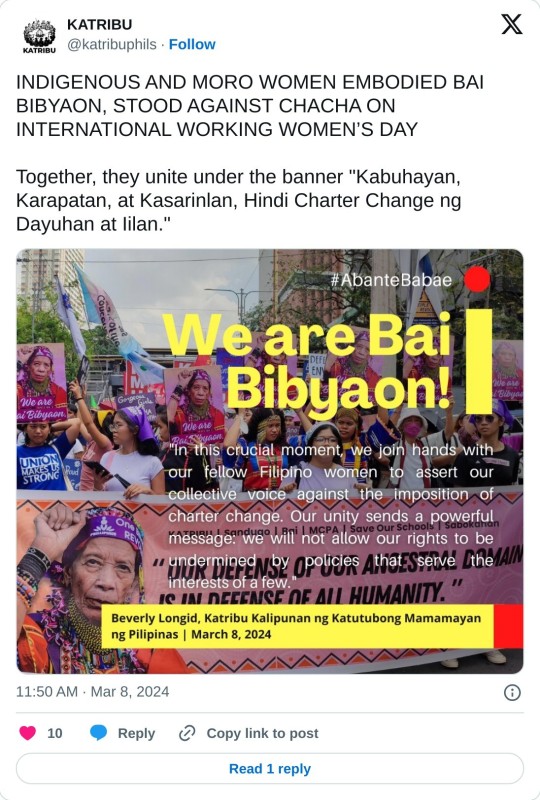

Katribu on Twitter @katribuphils:

INDIGENOUS AND MORO WOMEN EMBODIED BAI BIBYAON, STOOD AGAINST CHACHA ON INTERNATIONAL WORKING WOMEN’S DAY

Together, they unite under the banner "Kabuhayan, Karapatan, at Kasarinlan, Hindi Charter Change ng Dayuhan at Iilan."

Read the full release here: (FB link)

2024 Mar. 8

#abante babae#international working women's day#international women's day#philippines#land reform#labor rights#no to charter change#environmental issues#indigenous rights

5 notes

·

View notes

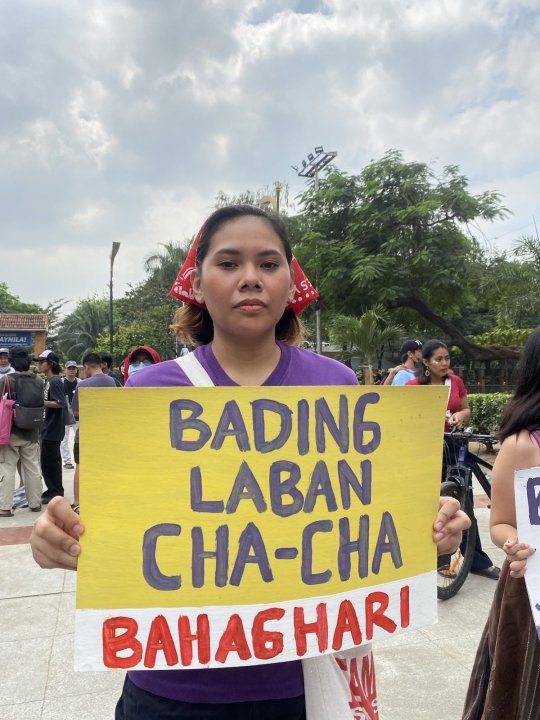

Photo

TIGNAN: LGBTQ+ activists sa pangunguna ng Bahaghari, nakikiisa sa Pandaigdigang Araw ng Kababaihang Anakpawis bitbit ang mga isyu ng LGBTQIA+ community at mamamayan para sa sahod, trabaho, ligtas na espasyo, pampublikong serbisyo, at karapatan!

LOOK: LGBTQ+ activists led by Bahaghari unite on International Working Women's Day carrying the issues of the LGBTQIA+ community and citizens for wages, jobs, safe spaces, public services, and rights!

-- Bahaghari Philippines, 8 Mar 2023

#iwwd 2023#international working women's day#women's liberation#queer liberation#philippines#labor rights#lgbt liberation

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Contrary to the myth that socialists have always ignored gender oppression, full women’s suffrage was first won by socialist feminists — and working-class revolt.

There are a lot of different ways to discredit working-class politics. As the continued promotion of the “Bernie Bro” myth illustrates, one of the most popular today is to claim that socialists ignore women’s oppression. Elaborate versions of this argument fill the news-media, Twitter, and academia. By focusing only on economic issues and class, we are told, the socialist movement has always marginalized women and their specific demands for equality.

Like all good liberal myths, these arguments rely on bad history. Working-class feminism has a long and rich legacy. For over a century working women fought for their own liberation through the socialist movement.

Few cases better illustrate this point (or have been more buried by history) than that of turn-of-the-century Finland. In 1906, through a mass general strike and working-class insurgency against the Russian Empire, it became the first nation in the world to grant full universal suffrage — i.e. the right to vote and run for office. Socialists were at the forefront.

The Finnish Buildup

Of all the lands of the tsarist empire, Finland had throughout the nineteenth century been allowed the most self-government and political freedom. Annexing Finland from Sweden in 1809, the Tsar granted its new dominion extensive autonomy, though the Russian regime maintained ultimate authority. Finland preserved its own constitution and most state functions were governed by Finns through their autonomous Senate. In 1863, a new Finnish parliament was established, though only a small percentage of the population was allowed to participate in its election.

A crucial turning point in Finnish history came in 1899. In February, the Tsar began to eliminate Finland’s special autonomous status, attempting to bring it under the same forms of administration as the rest of the empire. Soon a major Finnish national protest movement emerged against this “Russification.”

1899 also marked the emergence of the Finnish labor movement as an independent political force. After a string of labor strikes, the Finnish Workers Party was founded in July 1899. Whereas socialist parties across the Russian empire were banned and forced underground, the relative political freedom prevailing in Finland allowed the Workers Party to exist as a legal organization.

Though virtually all labor leaders in Finland supported the reestablishment of Finnish autonomy, the question of whether to collaborate, and on what basis, with the Finnish liberal “constitutionalists” against Russification became a major debate. While the constitutionalists essentially fought for a return to the pre-1899 status quo, the labor movement tied the national struggle to popular demands, such as improved conditions for urban and rural workers, the prohibition of alcohol, and the expansion of the vote.

One of the central points of contention between workers and constitutionalists was the issue of suffrage, from which all working people — both men and women — were excluded at that time. Constitutionalists refused to support universal suffrage. The conservative Association of Finnish Women led by women’s rights activist Alexandra Gripenberg, for example, argued that lower-class women were ignorant and prone to vice, therefore they had to be guided by their morally superior upper-class sisters.

In contrast, the Workers Party from its inception demanded suffrage for all: the right to vote and to run for office irrespective of wealth, gender, or nationality. In 1900, it helped found the socialist-led League of Working Women to involve working-class women in the labor movement, to develop their leadership capacity, and to help raise their demands.

Socialist leader Hilja Pärssinen, the working-women movement’s main theoretician, advocated a strict class-against-class perspective along the lines set out by the German Marxists August Bebel and Clara Zetkin. Pärssinen’s 1903 pamphlet on women and the vote made the case for irreconcilable class conflict: bourgeois women wanted only equality with upper-class men, while women workers wanted the vote to pass laws to improve their material conditions.

That same year, the Workers Party adopted a Marxist program, renamed itself the Social Democratic Party (SDP), and announced that if its suffrage demands were not met, it would resort to a general strike to win them.

The Great Strike of 1905

The Bloody Sunday massacre of unarmed protestors in St Petersburg on January 9, 1905 sparked revolt across the entire empire. This upheaval, more often than not under socialist leadership or influence, demanded better working conditions, political freedom, and a democratic republic — and it came close to toppling the increasingly discredited tsarist regime.

The revolution arrived relatively late in Finland. Inspired by the general strike in central Russia, Finnish railway workers walked off the job on October 29, 1905, setting into motion the “Great Strike.” By October 30, all of Finland was on strike, and effective power passed into the hands of strike committees and armed guards. The event radically transformed the consciousness of urban and rural working people. And perhaps nowhere was this transformation more pronounced than among women workers.

Palvelijatarlehti (The Maids’ Paper) noted:

The strike week was a wake-up week for the rights of women. … As soon as the strike began, women started to hold special meetings in which they debated their economic position, and these meetings were flooded by people. It was as if it took the breakout of the general strike to make women realize that it would depend on themselves whether the status of women improved or not.

Miina Sillanpää, the influential socialist leader of the maids’ association, noted that the week of the general strike accomplished among the maids “more than what could have been promoted in ten years of peaceful conditions.” Bourgeois society was particularly scandalized by the participation of their servants in the action, which shattered paternalistic notions of maids as members of the host family and represented the direct intrusion of the labor movement into their homes. In daily mass meetings in a Helsinki elementary school courtyard, thousands of servants came together to formulate their demands.

The call for full suffrage was legitimized by this mass female participation in all arenas of the strike, including in its top leadership; the Tampere Strike Committee, initially composed only of men, was quickly reorganized to include ten women and twelve men.

“We live in a wonderful period of time,” wrote Alma Malander in the SDP newspaper Kansan Lehti (The People’s Paper) in December 1905:

Peoples who were humble and satisfied to bear the burden of slavery have suddenly thrown off their yoke. Groups who until now have been eating pine bark, now demand bread. The oppressed demand justice! … Women, who have always been subordinate, suddenly get the idea that they really are equal with the other sex.

Faced with the imminent overthrow of the regime by a paralyzing labor strike, peasant rebellions, and army mutinies, the Tsar was forced on October 30 to promise civil liberties and a parliament for the whole empire. On November 4, the Tsar’s “November Manifesto” repealed the Russification of Finland, reestablishing the pre-1899 status quo — without guaranteeing that the new Finnish Parliament would be elected by the whole population.

Though constitutionalists and socialists had closely collaborated during the first days of the November Great Strike, this tenuous alliance quickly broke down into open conflict. After the Tsar’s “November Manifesto,” the constitutionalists pushed for an end to the strike, as their main demand — the restoration of pre-1899 “constitutional legality” — had been achieved. In contrast, the workers’ movement continued to demand universal suffrage and a unicameral parliament.

Having felt their power to shut down society, Finnish workers were determined to continue mobilizing. Immediately following the strike, the SDP began organizing mass demonstrations and building for a new general strike to ensure their political demands. The next half-year witnessed an unprecedented number of strikes, the rapid spread of socialist influence among tenant farmers and workers in the countryside, the creation of a workers’ Red Guard, and closer Finnish socialist collaboration with Russian Marxists. It was during this upsurge that the campaign for women’s suffrage reached its highest peak.

The Suffrage Struggle

Following the Great Strike, there was considerable and justifiable concern that women would be excluded in the upcoming elections. During the April 1905 suffrage reform bill discussions in the Finnish parliament, only the Peasants Estate had supported women’s suffrage, while other estates and the various constitutionalist parties all favored giving the vote only to men. The chair of the Parliamentary Reform Committee chosen in November 1905 to draft the new suffrage rules was liberal leader Robert Hermanson, an outspoken opponent of women’s suffrage. Women, he felt, were by nature emotional creatures prone to extremism and ill-suited for politics.

In this context, League of Working Women leaders argued that working-class women had to take the initiative to ensure that their demands were met:

We [working women] have to shout to the world that we are demanding the right to vote and to stand for election, and that we are not going to settle for anything less. Now is not the time for compromises, because if we are excluded now, we can be sure that it will remain that way for a long time.

By the end of 1905, the League, with the support of the whole Finnish Social Democracy, had organized 231 suffrage meetings across the nation with 41,333 participants. It called for a new general strike in the case that women were excluded from the vote, and it established a special women’s committee to start preparations.

It was announced that any male party members who opposed women’s suffrage would be denounced as collaborators of the bourgeoisie. Some female workers threatened to go on a cooking strike at home to force skeptical husbands to support their struggle. And there were even public statements made that if women were left out of the vote, women workers would, if necessary, strike on their own, even against the opposition of the other party members.

The influx of women into political life challenged traditional gender roles. Miina Sillanpää called on men to stay at home and watch the children to enable their wives’ participation in political meetings.

Perhaps the most powerful actions of the suffrage campaign were its mass demonstrations. On December 17, 1905, the League organized protests for women’s suffrage in sixty-three towns across the nation, bringing together over 22,000 demonstrators. A “National Women’s Declaration” written by the League’s leadership was sent out to be adopted by each rally.

The fate [of Finland] concerns us just as much as men. Is it any wonder that tens of thousands of us rise up to call for our rights, to demand for ourselves equality with men. A powerful cry is echoing across our country at this moment, from the large cities to the villages, showing that the majority of citizens support the heartfelt wishes of women. The demand of women for the vote and to run in elections will be silenced only when it is granted. The right to vote is a means for us to shut off the flow of alcohol, to raise the proletariat from material and psychological distress, to prepare the way for light and freedom.

The rallies continued into 1906 and the Finnish Social Democratic Party did not waver on demanding suffrage for all. But a new general strike did not ultimately prove necessary to win this demand, as the Parliamentary Reform Committee eventually announced that all women would be allowed to vote and run for office, despite considerable controversy within the Committee over the latter point in particular.

How can we explain this decision by a Finnish political elite that until then had consistently opposed universal suffrage? Put simply, they were forced into it. The pressure of the workers’ upsurge during and following the Great Strike of 1905, and the real threat of a new general strike, proved greater than elite opposition to universal suffrage.

That the suffrage decision had been imposed from below was openly admitted at the time. The influential banker and politician Emil Schybergson told the Parliamentary Reform Committee that the revolution had forced them to rush through a decision that might otherwise have waited another fifty years. Indeed, it took many more decades for other countries to grant full suffrage, including France (1944), Italy (1946), and Switzerland (1971).

The Tsar’s acceptance of the Finnish suffrage proposal on July 20, 1906 was similarly a victory imposed by revolutionary struggle. Such an act would have been inconceivable without ongoing mass rebellion across Russia, which flared up again that summer in a new wave of peasant revolts and army mutinies. Through this concession, the embattled tsarist regime hoped to quell unrest in Finland in order to concentrate its forces on putting down the revolution in the rest of the empire.

The suffrage campaign lasted all the way through 1907. In January, the League sent out a memorandum to its local branches, calling on them to ensure that the SDP electoral slates include a sufficient number of women candidates. By this time, over 18,000 women had joined the party, close to a quarter of the total membership.

The 1907 elections were swept by the Finnish Social Democracy. It won 37 percent of the vote — the highest of any party — and of the nineteen women in the new Parliament, nine were socialists. The latter were a remarkable group, all leaders of the League and most from humble backgrounds. Anni Huotari, Maria Laine, Maria Raunio, and Sandra Reinholdsson were seamstresses; Jenny Kilpianen was a weaver; Mimmi Kanervo was a maid, as had been Miina Sillanpää; Ida Ahlstedt was a baker and boarding-house operator; and Hilja Pärssinen was a school teacher.

Prominent feminists were, at best, ambivalent about the suffrage victory. The Finnish Women’s Association’s top leaders still stressed that Finnish working-class women were too backwards and unprepared for full suffrage. Alexandra Gripenberg declared to a 1907 women’s congress in Vienna that the entry of uneducated, plebeian women into Parliament was a “horrible” embarrassment. Most of the socialist MPs, Gripenberg lamented, were “formerly servants, factory hands, or seamstresses. … It was a mistake that so few really able and suitable women for the work in the Diet [Parliament] were elected. … If we had women lawyers, merchants, physicians, scientists, and so on, women’s words would have weighed more.”

Hilja Pärssinen, in contrast, traveled abroad to present the Finnish struggle as an unqualified victory and a vindication of a strict class-versus-class political perspective. She argued in the British newspaper Justice that “women who have to fight together with their men comrades for the abolition of the present capitalist system and the private ownership of the means of production cannot work together with women who support this very system.” In an interview with the Christian Science Monitor, she declared:

I should very much like through your paper to send a message to the American people, and to ask them why they have not yet granted the suffrage to women, and to urge upon them, out of a considerable practical experience of its value, the importance of making this great, and ultimately necessary, political change.

Pärssinen’s perspective was shared by the workers’ movement in Russia and beyond. For August Bebel, the German SPD leader and author of the influential work Women and Socialism, the events in Finland represented “the triumph of international socialism.” Similarly, Alexandra Kollontai at the 1908 First All-Russian Women’s Congress pointed to Finland to show that “in those countries where unlimited political rights for women have been achieved, this has been done only with the help of the social-democrats.”

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

reminder that the feminist struggle is intertwined with the abolition of capitalism

#proletarian feminism#marxist feminism#8 марта#international working women's day#international women's day

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

8 de Marzo: Día Internacional de la Mujer Trabajadora.

"Las mujeres no hemos sido meras espectadoras del drama social. Hemos sido actoras y lo seremos con más intensidad aún. (...) Reclamamos un puesto de lucha y consideramos ese derecho como un honor y un deber"

Eva Perón

Teatro Nacional Cervantes, 26 de julio de 1949

FELIZ DÍA INTERNACIONAL DE LA MUJER TRABAJADORA!!!!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Capitalism" from the See Red Women's Workshop

#my post#international women's day#international working women's day#radblr#radfems do touch#radfems please interact#radfem safe#radical feminism#radical feminist#radical feminists do interact#intersectional feminism#marxism#communism#socialism#marxism leninism#anti capitalism

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

International Working Womens Day!

Journée internationale des droits des femmes travailleuses!

👩🏿🚒👩🏿🔬👩🏾🏭

👩🏾🔧👩🏾🌾👩🏾🏫

👩🏾⚖️👩🏾🎓👩🏾⚕️

👷🏾♀️🧕🏾👩🏾💼

👩🏾✈️👩🏾🎤👩🏾🎨

👩🏾💻👩🏾🍳👩🏿🚀

#international women's day#journée internationale des droits des femmes#international working women's day#journée de la femme

1 note

·

View note

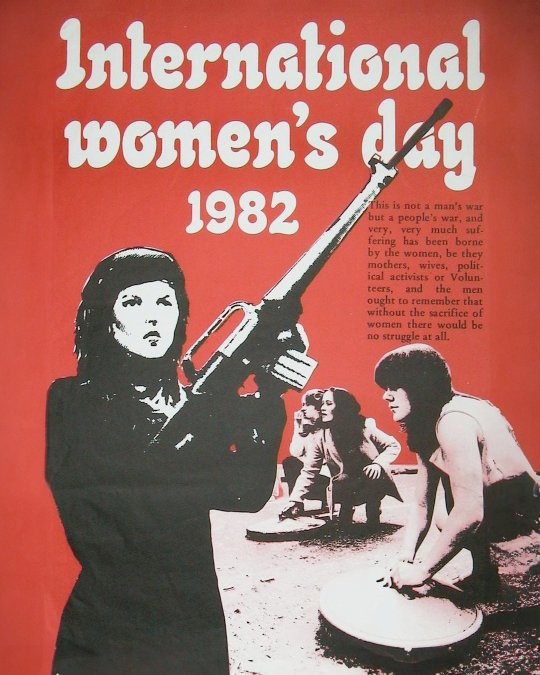

Text

#international women's day#international working women's day#posters#propaganda#feminism#women#women's rights#communism#pflp#palestine#eritrea#ireland#germany#revolution#eplf#ira#guerrilla#march 8th#march 8#8 de marzo

819 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ce avem de sărbătorit de Ziua Femeii în România, în anul austerității?

de Teodora Săvoiu

martie 2021

„Pâine și pace!”(1) sau originile socialiste ale sărbătorii de 8 Martie

Ziua Internațională a Drepturilor Femeii a fost instituită în 1910 la Conferința internațională a femeilor socialiste, drept zi dedicată manifestațiilor în care femeile solicitau dreptul de vot, dreptul de a fi alese în funcții publice și protestau împotriva discriminării la angajare. În Rusia anului 1917, pe fondul condițiilor materiale ce deveniseră insuportabile și a războiului neagreat de majoritatea populației, demonstrația muncitoarelor textiliste din Petrograd (astăzi Sankt Petersburg) s-a transformat în grevă generală: li s-au alăturat muncitorii din celelalte industrii și oameni din alte sectoare ale populației. Greva generală a catalizat abdicarea țarului rus 7 zile mai târziu, rămânând cunoscută drept Revoluția din Februarie, după calendarul de rit vechi (8-16 martie în calendarul actual). În aceste condiții, femeile au câștigat dreptul de vot, cel mai devreme în Europa, și au inițiat procesul prin care Rusia urma să se retragă din război și să fie restructurată așa încât să permită dezvoltarea unui sistem economic complet nou la acea vreme.

Poate că din aceste motive 8 Martie a căpătat nuanțe de sărbătoare în blocul estic și semnificația de luptă pentru emancipare s-a diminuat. Pentru un timp, s-ar putea spune, femeile din blocul socialist s-au bucurat de cea mai mare putere de până atunci – libertate pe plan politic, militar, la locul de muncă și libertate asupra propriului corp – în timp ce femeile din vest încă se luptau să le fie acordate aceste drepturi, iar munca domestică și de îngrijire erau încă parte din datoria implicită a femeii, și nu ceva ce putea fi socializat sub forma creșelor și grădinițelor. Totuși, nici URSS și niciunul din statele partenere nu au fost utopii feministe, drept dovadă nefericitul decret 770 din România socialistă (prin care întreruperea de sarcină trecea în afara legii), sau anumite reminiscențe ale culturii patriarhale prezente în aceste societăți, perpetuate în ciuda egalității formale și care au înflorit cu o nouă forță după `89, odată cu puterea instituțiilor religioase.

În Occident, Ziua internațională a drepturilor femeii nu are aceleași valențe de sărbătoare, dar nici neapărat de luptă, deoarece a fost adoptată în afara cercurilor socialiste abia 1967 – când lupta pentru egalitate a trecut în mainstream. În fapt, în cultura populară 8 martie e o sărbătoare minoră, dedicată unei idei vagi și comerciale de feminitate. Comparativ, la noi ziua femeii a trecut prin mai multe etape. De la zi de protest la sărbătoare a luptelor câștigate pe calea emancipării, la Ziua Mamei (există o linie fină între aprecierea muncii invizibile a mamelor și idealizarea mamei drept singurul tip de femeie demnă de respect, și putem spune că bărbații ce luau deciziile în privința sărbătorilor publice au încurcat rău oalele ideologice), iar în timp Ziua femeii a devenit parte dintr-un trio menit să sărbătorească mai mult venirea primăverii, iar pe femeie doar prin ochii altcuiva, în forma idealizată cu care am fost obișnuiți. Abia în ultimii 20-30 de ani, ne-am aliniat cu cultura vestică și 8 Martie a devenit una din cele 3-4 excelente oportunități de marketing pentru cam orice tip de produse și servicii, de la broșe, la bere, la credite, la mașini de spălat vase.

„Cade una, sărim toate!”(2)

În acest context cultural se situează demonstrația „Misoginie, cealaltă pandemie” de anul acesta, organizată de colectivul #mulțumescpentruflori. În tradiția internațională a zilei de 8 martie drept zi de protest, participantele și participanții trag un semnal de alarmă asupra unor fenomene esențiale care au condus la înrăutățirea condiției materiale a femeilor încă de la începutul pandemiei. În tandem cu alte acțiuni similare și greve ce au avut loc în alte orașe din țară și din Europa, oamenii și organizațiile prezente luni în fața guvernului se poziționează ferm împotriva măsurilor de austeritate -despre care știm din 2010 că nu aduc niciun beneficiu economic majorității populației- , și atrag atenția asupra unor probleme ce au afectat în mod disproporționat femeile, dar care sunt conectate cu probleme care ne afectează pe noi toți, în mod sistemic. Concentrându-se pe mai multe domenii de lucru și categorii sociale, aceste proteste îndeamnă la solidaritate între femei și solidaritate între lucrătoare și lucrători.

Pe scurt, lista de revendicări vizează munca esențială și de îngrijire, sănătatea și drepturile reproductive, violența domestică și sexuală și locuirea.

Să începem cu expresia care a devenit deja un clișeu în ultimul an: ceea ce numim muncă esențială este în majoritate muncă plătită cu salariul minim, care în sine este mai mic decât esențialul (necesarul) pe care cineva îl cheltuie lună de lună pentru a se întreține în orașele din România. Deci salariul minim trebuie să crească. Munca de îngrijire, și ea parte din munca esențială și subevaluată, se împarte în mai multe categorii. Aici găsim atât munca în sănătate, în educație preuniversitară, asistență socială (majoritatea femei), cât și munca domestică de îngrijire (în general repartizată femeilor) și munca lucrătoarelor sexuale, în prezent nerecunoscută drept muncă. De aici rezultă următoarele revendicări: alocarea a 10% din PIB pentru Sănătate și 6% pentru educație, subvenții suplimentare pentru mamele singure în timpul pandemiei, finanțarea prioritară a construirii de creșe și grădinițe în toată țara, sprijinirea copiilor ai căror părinți lucrează în străinătate, plata corectă a angajaților din sistemul sanitar și cel de asistență socială, dezincriminarea muncii sexuale și recunoașterea ei ca muncă pentru ca femeile din acest domeniu să aibă acces la aceleași beneficii sociale ca toți ceilalți și pentru a le proteja astfel de abuzurile poliției.

În privința sănătății și a drepturilor reproductive, știm deja care este problema și ce s-a înrăutățit în timpul stării de urgență. Accesul femeilor la întreruperi de sarcină este oricum limitat în spitalele și clinicile de stat, iar de anul trecut a devenit cu atât mai limitat. În afară de acest lucru, accesul la servicii medicale esențiale nu este întotdeauna accesibil celor în situație economică precară, și nu este mereu accesibil celor ce fac parte dintr-o minoritate etnică sau sexuală. Educația sexuală pentru tineri adaptată vârstei și nevoiloracestora este o altă măsură necesară, care ar scădea riscul fetelor minore la sarcină dar și riscul copiilor de orice gen de a fi abuzați de către un adult care profită de poziția sa de putere. Aici se adaugă asigurarea accesului la produse sanitare pentru menstruație și produse de contracepție. Solicitările sunt detaliate în manifest, dar pe scurt este nevoie ca sistemul de sănătate să poată oferi servicii esențiale (tratamente, întreruperi de sarcină, terapie) accesibile tuturor și tratamente decontate complet pentru persoanele cu suferințe cronice sau psihice, indiferent de gen, abilitate, etnie, sexualitate sau alte delimitări arbitrare.

Problema violenței domestice s-a agravat în ultimul an – după două luni de stat în casă citeam despre creșterea cu 50% a cazurilor, mai întâi în Italia, apoi aici și în aproape toată lumea. Cum se explică? Păi violența domestică se petrece în casă, acolo unde ni s-a spus să stăm pentru binele nostru colectiv, iar statul român oricum are un sistem prea puțin pregătit să răspundă nevoilor supraviețuitoarelor sau menit să prevină violența. Este nevoie de mai multe centre de asistență și adăposturi de urgență pentru supraviețuitoare, de servicii psihologice pentru agresori, de asigurarea accesului femeilor la justiție și nu doar atât. Cât despre violența sexuală – lăsând deoparte faptul că riscul de a fi agresată sexual de cineva cunoscut este mult mai mare decât de un străin, cazurile de violență sexuală împotriva minorelor și minorilor trebuie tratate în mod specific. În plus, formarea personalului instituțiilor cu care supraviețuitoarele interacționează trebuie să includă informații din domeniul drepturilor omului, din motive lesne de înțeles.

Ultima categorie de probleme și revendicări este, poate, cea mai importantă pentru o populație nevoită să se adăpostească în timpul unei pandemii: locuirea. Trăim într-un oraș ale cărui clădiri sunt simultan în paragină și noi-nouțe, supraaglomerate și complet vacante, turnuri de sticlă și barăci din placaj. În Cluj e la fel. Chiriile, dar și prețurile apartamentelor sunt umflate din cauza gentrificării, iar unii oameni nu-și permit să plătească nici chiria din salariul minim pe care-l câștigă muncind zi de zi. Dar ne-am dus prea departe și am presupus că vorbim despre cineva care are o locuință. Destui oameni nu au unde sta ”în casă”, în ciuda gingașelor recomandări și restricții de siguranță. Mulți dintre noi locuim în condiții de supraaglomerare sau în locuințe improprii, fără acces la utilități. Locuim la prieteni, sau în mașină. Sau locuim cu agresorul și apoi fugim de acasă. Cei care simt cel mai puternic violența sistemului politic și economic actual trăiesc în parc sau printre gunoaie. Iar în București, numărul de locuințe sociale este de 10 ori mai mic decât numărul de oameni care depun dosar pentru a solicita ajutor din partea administrației locale. Numărul celor care au nevoie de locuință, dar nu depun dosar, este cu atât mai mare. Și cu toate acestea chiriile au continuat să crească, asemeni evacuărilor care produc și mai mulți oameni fără adăpost, dar permit (uneori) dezvoltarea vreunui nou proiect imobiliar profitabil pentru cei puțini – o clădire de birouri, un complex de blocuri ridicat pe fugă și pe pile… după posibilități.

Din aceste motive, solicitările protestatarelor și protestatarilor sunt acestea: relocarea imediată și conform nevoilor a persoanelor care au trecut prin violență domestică, locuințe și servicii socio-medicale pentru persoanele fără adăpost, sistarea evacuărilor din locuințe, eliminarea chiriilor la stat pentru cei și cele care se confruntă cu probleme financiare, controlul chiriilor private și accesul universal și fără restricții la toate utilitățile indiferent de situația contractuală sau de datorii. Pe scurt, este nevoie de locuințe adecvate și accesibile financiar pentru toți și toate, fără supraaglomerare și fără condiții precare.

Categoriile acestea de revendicări trebuie privite unitar, deoarece niciuna dintre problemele menționate nu poate fi adresată și rezolvată pe termen lung fără a lua în calcul contextul în care se situează. Începând cu subfinanțarea sistemului sanitar și al celui de educație, continuând cu accesul limitat la aceste servicii, cu situația precară în care se găsește acea jumătate aproximată din români care câștigă salariul minim pe economie (atât în sectorul de stat cât și cel privat) – toți suntem puși sub o presiune extraordinară să pentru a ne asigura traiul de zi cu zi, la care se adaugă costuri suplimentare când ne îmbolnăvim, când muncim departe de casă, când îi îngrijim pe cei de lângă noi, sau când suntem puși în pericol în propria locuință. Cu toate acestea, contribuția femeilor continuă să țină societatea pe linia de plutire și continuă să fie subevaluată, într-un sistem economic care pune profitul înaintea bunăstării umane (și căruța înaintea cailor).

În fața violenței austerității, suntem „sub același acoperiș”(3)

Totuși, protestul feminist din 8 martie nu a fost nici pe departe prima demonstrație locală anti-austeritate de anul acesta. Sindicate și colective din varii domenii de activitate au încercat să atragă atenția guvernanților asupra deciziilor pernicioase din ultima perioadă, și să ne atragă nouă, oamenilor de rând, atenția asupra lipsei de putere decizională concretă pe care o avem asupra propriilor vieți atunci când interesele noastre nu se aliniază cu cele ale capitalului.

Dacă ne îndreptăm privirea spre Europa, dar și alte părți ale lumii(4) (sau în istoria recentă), ne dăm seama din ce în ce mai mult că drepturile și libertățile nu se votează, și că drepturile neapărate se pierd pe nesimțite. Au trecut cam o sută de ani de când a fost instituită ziua de muncă de opt ore -și nu mai mult-, de pildă. Treizeci de ani de când am recâștigat dreptul de a întrerupe o sarcină, în România. Egalitatea tuturor în fața legii există – formal. Dreptul fiecărui copil la educație este universal – pe hârtie. Anul acesta mulți dintre noi au aflat, în timp ce alții mai puțin feriți știau deja, că drepturile formale nu valorează nimic atunci când nu corespund unor drepturi existente în realitate. Dar menirea acestor acțiuni critice nu este să ne arunce într-o spirală a cinismului, dimpotrivă: este un apel la solidaritate.

Lista completă a revendicărilor se găsește aici:

https://www.facebook.com/events/916028105832134

(1)una dintre sintagmele consemnate în istorie drept scandări ale femeilor participante la greva generală din martie 1917

(2)denumirea manifestației de la Cluj, dar și una din scandările auzite la București

(3)titlul manifestului dreptății locative pentru 8 martie: https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid=3904904436237018&id=675979395796221

(4)greva generală inițiată de țărani/agricultori în India încă persistă, de pildă

#8 marzo#8 march#international women's day#international working women's day#international solidarity#feminist history#feminism#general strike

0 notes

Text

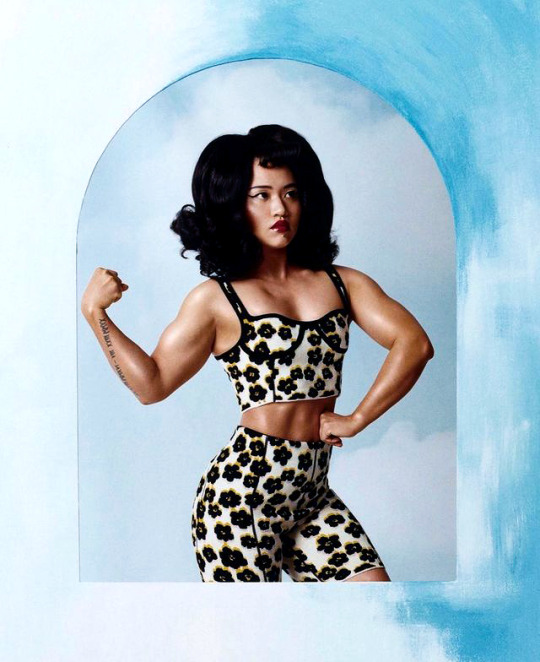

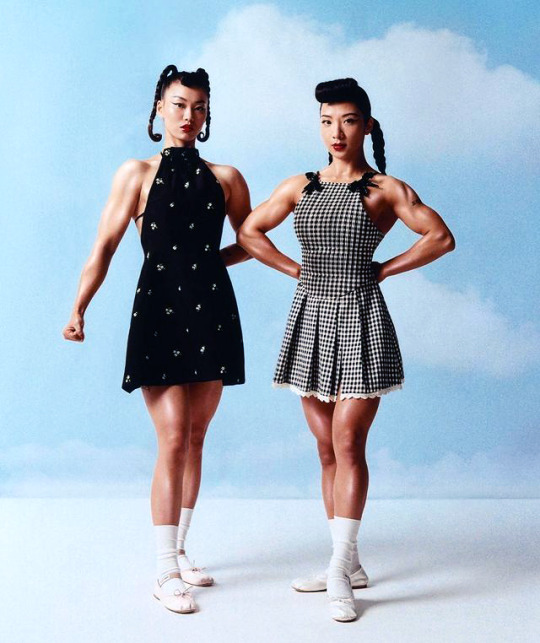

MODERN WEEKLY STYLE CHINA

Photographer: Hailun Ma; Stylist: Macci Leung; Makeup: Yooyo Keong Ming; Hair: Zhou Xue Ming; Art Director: Doris He; Models: Wai Wai, Annie, Una, Juan, Hei Wa, Bonnie, Ginny

#for my own sanity. look at THEM#this is the perfect photoshoot#also the photographer is from xinjiang and does incredible photos on it 100 per cent recommend checking out her work#photography#fashion#international women’s day

35K notes

·

View notes

Text

It's International Women's Day!

Started as International Working Women's Day by the early American socialist movement.

Celebrate by organizing with women coworkers, and keep organizing everyday.

Remember: smash capitalism, smash patriarchy.

0 notes

Photo

ICYMI: Kaisa ang Gabriela Youth Laguna, tagumpay ang Southern Tagalog caravan na pinangunahan ng Gabriela Timog Katagalugan bilang pagdiriwang para sa Pandaigdigang Araw ng Kababaihang Anakpawis!

Hindi napigilan ng pang-iintimida ng pulisya ang hanay ng mga kababaihan sa pakikipaglaban para sa sahod, trabaho, kabuhayan edukasyon, kaligtasan, at karapatan! Tagumpay na naisagawa ang programa mula San Pedro, Biñan, Sta Rosa, Cabuyao, Calamba, at San Pablo.

Hindi rito natatapos ang pakikipaglaban ng mga kababaihan kaisa ang bawat mamamayang Pilipino. Patuloy ang pagsulong para sa ating batayang karapatan! Sama-sama nating papandayin ang lipunang malaya sa paghihirap, pang-aapi, at pang-aabuso! Abante, babae! Palaban, Militante!

ICYMI: Together with Gabriela Youth Laguna, the Southern Tagalog caravan led by Gabriela Southern Tagalog had a successful celebration of International Women's Day! Police intimidation did not stop the ranks of women from fighting for wages, jobs, livelihoods, education, safety, and rights! The program was successfully implemented in San Pedro, Biñan, Sta Rosa, Cabuyao, Calamba, and San Pablo. The fight of women alongside all Filipino citizens does not end here. Continue to advance basic rights! Together we will forge a society free from suffering, oppression, and abuse! Forward, women! Fight militantly!

-- Gabriela Youth Laguna, 9 Mar 2023

#iwwd 2023#international working women's day#philippines#youth activism#labor rights#women's liberation#laguna

10 notes

·

View notes