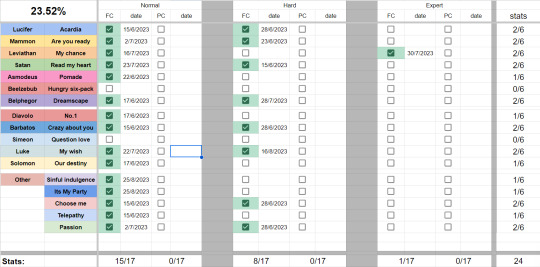

#i added a total count in the right bottom corner and a total percentage completed in the top left!!!!

Text

hehe look at my lil OM!NB full combo table =w=bb

#i added a total count in the right bottom corner and a total percentage completed in the top left!!!!#+ 'its my party' bc that only joined in the lesson that's released today#YIPPEE#theres another tab where i have screenshots of every FC! which is why i have FC'd some songs ingame that arent on here....#i forgor to screenshot those and without proof i wont add it onto this docu =w=bb i want the screen with the specified perfect/great/etc#i recently FC no.1 on hard but forgot to screenshot Y-Y a true loss#sillyposting#YAY EXCEL!!!!#google spreadsheets actually but >:P#everything is automated!! i only click to check and add a date =w=bb

0 notes

Link

As a working Sinologist, each time I look up a word in my Webster's or Kenkyusha's I experience a sharp pang of deprivation Having slaved over Chinese dictionaries arranged in every imaginable order (by K'ang-hsi radical, left-top radical, bottom-right radical, left-right split, total stroke count, shape of successive strokes, four-comer, three-comer, two-corner, kuei-hsieh, ts'ang-chieh, telegraphic code, rhyme tables, "phonetic" keys, and so on ad nauseam), I have become deeply envious of specialists in those languages, such as Japanese, Indonesian, Hindi, Persian, Russian, Turkish, Korean, Vietnamese, and so forth, which possess alphabetically arranged dictionaries Even Zulu, Swahili, Akkadian (Assyrian), and now Sumerian have alphabetically ordered dictionaries for the convenience of scholars in these areas of research

Webmaster's note: This essay was instrumental in leading to production of the

ABC Chinese-English Comprehensive Dictionary

, which is by far my favorite Mandarin-English dictionary.

It is a source of continual regret and embarrassment that, in general, my colleagues in Chinese studies consult their dictionaries far less frequently than do those in other fields of area studies. But this is really not due to any glaring fault of their own and, in fact, they deserve more sympathy than censure. The difficulties are so enormous that very few students of Chinese are willing to undertake integral translations of texts, preferring instead to summarize, paraphrase, excerpt and render into their own language those passages which are relatively transparent Only individuals with exceptional determination, fortitude, and stamina are capable of returning again and again to the search for highly elusive characters in a welter of unfriendly lexicons. This may be one reason why Western Sinology lags so far behind Indology (where is our Böthlingk and Roth or Monier-Williams?), Greek studies (where is our Liddell and Scott?), Latin studies (Oxford Latin Dictionary), Arabic studies (Lane's, disappointing in its arrangement by "roots" and its incompleteness but grand in its conception and scope), and other classical disciplines. Incredibly, many Chinese scholars with advanced degrees do not even know how to locate items in supposedly standard reference works or do so only with the greatest reluctance and deliberation. For those who do make the effort, the number of hours wasted in looking up words in Chinese dictionaries and other reference tools is absolutely staggering. What is most depressing about this profligacy, however, is that it is completely unnecessary. I propose, in this article, to show why.

First, a few definitions are required, What do I mean by an "alphabetically arranged dictionary"? I refer to a dictionary in which all words (tz'u) are interfiled strictly according to pronunciation. This may be referred to as a "single sort/tier/layer alphabetical" order or series. I most emphatically do not mean a dictionary arranged according to the sounds of initial single graphs (tzu), i.e. only the beginning syllables of whole words. With the latter type of arrangement, more than one sort is required to locate a given term. The head character must first be found and then a separate sort is required for the next character, and so on. Modern Chinese languages and dialects are as polysyllabic as the vast majority of other languages spoken in the world today (De Francis, 1984). In my estimation, there is no reason to go on treating them as variants of classical Chinese, which is an entirely different type of language. Having dabbled in all of them, I believe that the difference between classical Chinese and modern Chinese languages is at least as great as that between Latin and Italian, between classical Greek and modern Greek or between Sanskrit and Hindi. Yet no one confuses Italian with Latin, modern Greek with classical Greek, or Sanskrit with Hindi. As a matter of fact there are even several varieties of pre-modern Chinese just as with Greek (Homeric, Horatian, Demotic, Koine), Sanskrit (Vedic, Prakritic, Buddhist Hybrid), and Latin (Ciceronian, Low, Ecclesiastical, Medieval, New, etc.). If we can agree that there are fundamental structural differences between modern Chinese languages and classical Chinese, perhaps we can see the need for devising appropriately dissimilar dictionaries for their study.

One of the most salient distinctions between classical Chinese and Mandarin is the high degree of polysyllabicity of the latter vis-a-vis the former. There was indeed a certain percentage of truly polysyllabic words in classical Chinese, but these were largely loan- words from foreign languages, onomatopoeic borrowings from the spoken language, and dialectical expressions of restricted currency. Conversely, if one were to compile a list of the 60,000 most commonly used words and expressions in Mandarin, one would discover that more than 92% of these are polysyllabic. Given this configuration, it seems odd, if not perverse, that Chinese lexicographers should continue to insist on ordering their general purpose dictionaries according to the sounds or shapes of the first syllables of words alone.

Even in classical Chinese, the vast majority of lexical items that need to be looked up consist of more than one character. The number of entries in multiple character phrase books (e.g., P'ien-tzu lei-pien [approximately 110,000 entries in 240 chüan], P'ei-wen yün-fu [roughly 560,000 items in 212 chüan]) far exceeds those in the largest single character dictionaries (e.g., Chung-hua ta tzu-tien [48,000 graphs in four volumes], K'ang-hsi tzu-tien [49,030 graphs]). While syntactically and grammatically many of these multisyllabic entries may not be considered as discrete (i.e. bound) units, they still readily lend themselves to the principle of single-sort alphabetical searches. Furthermore, a large proportion of graphs in the exhaustive single character dictionaries were only used once in history or are variants and miswritten forms. Many of them are unpronounceable and the meanings of others are impossible to deter- mine. In short, most of the graphs in such dictionaries are obscure and arcane. Well over two-thirds of the graphs in these comprehensive single character dictionaries would never be encountered in the entire lifetime of even the most assiduous Sinologist (unless, of course, he himself were a lexicographer). This is not to say that large single character dictionaries are unnecessary as a matter of record. It is, rather, only to point out that what bulk they do have is tremendously deceptive in terms of frequency of usage.

Just to give one example, only 622 characters account for 90% of the total running text of Lao She's Rickshaw Boy(Lo-t'o hsiang-tzu) and 1681 graphs account for 99%. Altogether there are a total of 107,360 characters in Rickshaw Boy but only 2,413 different graphs. Compare this with the 660,273 total characters in the four volumes of Mao Tse-tung's Selected Works which are composed of only 2,981 different graphs. The figure is actually not much different for the bulk of classical Chinese writings (Brooks). In 700 of the best-known T'ang poems, a considerable number by a variety of poets, there are no more than 3,856 different graphs (based on Stimson). It is generally acknowledged that a passive command of about 5,500 characters is sufficient for reading the overwhelming majority of literary texts. Five to six thousand distinct graphs are certainly quite enough for anyone to cope with, but they are a far cry from fifty to sixty thousand.

Functional literacy (the ability to read newspapers, letters, signs, and so forth) in today's world requires that an individual command a knowledge of no more than 1,500-2,000 graphs (cf. Ho, p. 33). Not surprisingly, this figure is approximately the same as the amount of jōyō or tōyō kanji(characters approved for common use by the Japanese Ministry of Education). It would appear that the mind of the common man rebels at the memorizaton of larger numbers of graphs. Two or three years out of high school, most Japanese -- including those who go on to college -- can only reproduce about 500-700 graphs. This number goes down in successive years as they increasingly resort to kana or romaji to express themselves. Even the most highly literate Chinese scholars can almost never recognize more than 10,000 characters and the person who can accurately produce as many as 5,000 is exceedingly rare. It is a simple fact that the written vocabulary of modem Chinese texts consists largely of words that can be written down using no more than 3,500 different characters....

0 notes

Link

via FiveThirtyEight

Welcome to The Riddler. Every week, I offer up problems related to the things we hold dear around here: math, logic and probability. There are two types: Riddler Express for those of you who want something bite-size and Riddler Classic for those of you in the slow-puzzle movement. Submit a correct answer for either,1 and you may get a shoutout in next week’s column. If you need a hint or have a favorite puzzle collecting dust in your attic, find me on Twitter.

Quick announcement: Have you enjoyed the puzzles in this column? If so, I’m pleased to tell you that we’ve collected many of the best, along with some that have never been seen before, in a real live book! It’s called “The Riddler,” and it will be released in October — just in time for loads of great holidays. It’s a physical testament to the mathematical collaboration that you, Riddler Nation, have helped build here, which in my estimation is the best of its kind. So I hope you’ll check out the book, devour the puzzles anew, and keep adding to our nation by sharing the book with loved ones.

And now, to this week’s puzzles!

Riddler Express

From Freddie Simmons, a guessing game:

Take a standard deck of cards, and pull out the numbered cards from one suit (the cards 2 through 10). Shuffle them, and then lay them face down in a row. Flip over the first card. Now guess whether the next card in the row is bigger or smaller. If you’re right, keep going.

If you play this game optimally, what’s the probability that you can get to the end without making any mistakes?

Extra credit: What if there were more cards — 2 through 20, or 2 through 100? How do your chances of getting to the end change?

Submit your answer

Riddler Classic

From Steven Pratt, use your econ, win some cash:

Ariel, Beatrice and Cassandra — three brilliant game theorists — were bored at a game theory conference (shocking, we know) and devised the following game to pass the time. They drew a number line and placed $1 on the 1, $2 on the 2, $3 on the 3 and so on to $10 on the 10.

Each player has a personalized token. They take turns — Ariel first, Beatrice second and Cassandra third — placing their tokens on one of the money stacks (only one token is allowed per space). Once the tokens are all placed, each player gets to take every stack that her token is on or is closest to. If a stack is midway between two tokens, the players split that cash.

How will this game play out? How much is it worth to go first?

A grab bag of extra credits: What if the game were played not on a number line but on a clock, with values of $1 to $12? What if Desdemona, Eleanor and so on joined the original game? What if the tokens could be placed anywhere on the number line, not just the stacks?

Submit your answer

Solution to last week’s Riddler Express

Congratulations to

Jonathan Hegarty

of Cedar Grove, New Jersey, winner of last week’s Riddler Express!

Where on Earth can you travel 1 mile south, then 1 mile east, then 1 mile north, and arrive back at your original location?

You can do this at the North Pole, for starters — that’s the easy one. But there is also an infinite number of other such points on the planet that allow for this paradoxical navigation. Specifically, any point that is 1+1/(2nπ) miles from the South Pole, where n = 1, 2, 3, …

Our winner, Jonathan, explained how this works. At the North Pole, after walking a mile south (which could be any direction, since you’re as far north as possible) and a mile east, you would still be exactly 1 mile south of where you started. Therefore, when you walk north, you end up at your original position.

However, you can also do something similar if you are near the South Pole. We’re looking for a place that, after walking our first mile south, leaves us in position to walk 1 mile east and have that mile be a perfect circle around the South Pole. In other words we’re looking to start in a place that makes the circumference of the circle around the South Pole 1 mile, making the radius of that circle (and the distance to the South Pole) 1/2π. Once completing this circle, you are free to walk back north 1 mile to your starting point, which would be 1+1/2π miles in any direction from the South Pole. But you’re not limited to just taking a single circle around the South Pole. What if you want to walk a half-mile circle around the South Pole twice? In that case, you would want the radius of that circle to be 1/4π, so you would be starting 1+1/4π miles from the South Pole. Continuing that logic, you can really start at any place that is 1+1/(2nπ) miles from the South Pole, where n is any positive integer and the number of times you wish to walk around the South Pole.

Brrr.

Solution to last week’s Riddler Classic

Congratulations to

Marissa James

of Berkeley, California, winner of last week’s Riddler Classic!

Last week found us in the factory of Riddler Rugs, where 100-by-100-inch random rugs are crafted by sewing together a bunch of 1-inch squares. Each square is one of three colors and is chosen for the final rug randomly. Riddler Rugs also wants its rugs to look random, so it rejects any finished rug that has a four-by-four block of squares of the same color. What percentage of rugs should we expect to be Riddler Rugs rejects? (Say that 10 times fast.)

Riddler Rugs will reject about 0.066 percent of its rugs, or roughly 1 rug in every 1,500.

We can arrive at that number in two different ways: a simple approximation and then a somewhat more involved one. My editor could barely stomach the former, let alone the latter, so tread carefully.

Let’s start with the approximation. Consider the fact that each of the squares in the top 97 “rows” and the left-most 97 “columns” of the quilt define an upper left corner of a four-by-four block. The squares are almost all part of other blocks, too, but what matters here is their role in the upper left of a block. (There are 97 of them because the three bottom rows and three right-most columns “start” blocks that extend off the edge of the rug, so we don’t count those.) Multiply 97 by 97, and you get 9,409 four-by-four blocks to use as a baseline for calculations.

The chances that any one of these blocks is all one color are the same as the chances that 15 of the squares in the four-by-four block match the color of the first upper-left square. With our three colors, that chance is equal to \((1/3)^{15}\). Therefore, the chance that there are no one-color blocks out of the 9,409 is \((1-(1/3)^{15})^{9,409}\), so the chance that there is a one-color block (and thus that the rug is rejected) is \(1-((1-(1/3)^{15})^{9,409})\), or about 0.0006555, or about our 0.066 percent.

The other way to get at this solution is to think about the whole universe of possible rugs. To do that, we have to determine the numerator (how many rejectable rug combinations there are) and the denominator (the number of total possible rug color combinations). The latter is easy to calculate: There are \({3^{100}}^2\) possible rugs (three colors to choose from, and 100 rows and columns of squares in each rug).

Figuring out the numerator is where it gets trickier. We need to consider every possible one-color block that will cause the rug to be rejected, along with every possible rug that includes that “bad” block. To do that, consider that there are \(97^2\) possible bad blocks, and three ways they each could be bad. Those bad blocks automatically make a rug a reject, but it matters what the rest of the rug looks like, since we are trying to do a full accounting of every possible rug. We can use our old denominator formula here, with one small tweak: \(3^{(100^2-16)}\), with the “16” representing the number of squares we know the color of already (the 4×4 reject block).

With all that in hand, we’re nearly done. Multiply the two elements of our numerator, and divide it over the denominator, and you get a formula for the proportion of rejected rugs: \((97^2\cdot 3)\cdot (3^{(100^2-16)})/({3^{100}}^2)\). That simplifies to \(97^2/3^{15}\), which is about 0.0006557, or again about our estimate of 0.066 percent.

And, as usual, you could also turn to a computer simulated approximation. Stephanie Valenzuela was kind enough to share her Python-based approach.

So how does this process scale? Riddler Rugs, I’m not ashamed to say, is in it for the money and has plans to produce way more than just one measly random rug. One rug’s not cool. You know what’s cool? A million rugs. And we’d prefer to not reject any, if we can help it.

Laurent Lessard plotted the probability of rejecting no rugs out of a million produced. With our initial three colors, we’re nearly sure to reject at least some rugs. But if we expanded our fabric palette to six or even seven colors — ROYGBIV, say — Riddler Rugs would have an excellent chance to produce a million rugs without rejecting even a single one.

Want to submit a riddle?

Email me at [email protected].

0 notes

Text

Here’s why the Saints will beat the Panthers in a decisive NFC South matchup

Two 8-3 battling for supremacy in the division, but it all comes down to one big issue. Retired NFL lineman Geoff Schwartz takes a closer look.

It’s a myth that NFL games in November and December count more. They all count the same. However, games down the stretch take on an added feeling of importance. And this weekend in the NFC, we have some matchups that are super important and could go a long way in deciding division and/or home field advantage.

The biggest one is in the NFC South between the Panthers at the Saints, both 8-3 teams.

The Saints beat the Panthers, 34-13, in Week 3. Entering that game, the Panthers were 2-0 and the Saints 0-2. Those Saints looked like the Saints of the last few years — an offense with zero defense. New Orleans forced three turnovers and made Cam Newton uncomfortable all day on the way to the victory. That was the first of eight straight victories for the Saints, led by their defense and running game, before losing on the road to the Rams last week.

The Panthers have taken a different road to 8-3, one slightly less predictable. They have looked unbeatable in stretches, with wins at New England and Detroit in back-to-back weeks, only to lose on the road to the Bears, 17-3.

The Panthers are what I thought they’d be. Defensively, outstanding. Playmakers all over the place. On offense, they are as Cam Newton goes. If Cam is up, they are up. If Cam is down, they are down. The Panthers have surprisingly struggled to run the ball this season, and like I predicted (humble brag), it has taken 10 weeks to figure out how to use Christian McCaffery.

Will the Saints lean on their lethal running game?

The Saints are second in total offense; the Panthers are second in total defense. Saints are third in rushing; the Panthers are third in rushing defense. You can keep playing this game throughout the matchup.

The Saints rushing attack is led by the two-headed monster of Mark Ingram and rookie Alvin Kamara. Since Week 6, the Saints running game is first in the NFL in yards per game, yards per carry, and touchdowns.

As usual, when you have a good ground attack, your offensive line is beastly, which is the case with the Saints. Here’s a power run that went to the house against Washington. Watch the entire right side of the line collapse.

The Saints added former Lions guard Larry Warford to the lineup in free agency. They are currently averaging a remarkable 6.18 yards rushing behind him, second in the NFL.

When is the last season anyone started a conversation about the Saints with the rushing attack? Maybe never.

The Saints still have Drew Brees at the helm of this offense, and the passing attack is as potent as ever when called upon. Brees is completing 71 percent of passes with a passer rating of 104.1. This offense is lethal.

Is the same old dominant Carolina defense enough?

Carolina’s defense is exactly what I thought they’d be entering the season. Tough against the run, can rush the passer (fourth in sacks) and have legitimate ability to defend the pass. James Bradberry has become a legitimate lockdown corner. This defense has added more pressure wrinkles this season with new defensive coordinator Steve Wilkes.

My favorite defensive player in the NFL to watch is Luke Kuechly. He’s constantly in the backfield on run plays.

Kuechly is also the most instinctive defender in the league. Here he is running the route for the Dolphins tight end and picks off Jay Cutler.

As good as the Panthers rush defense has been, they do still allow 3.9 yards a carry, which is slightly high for a top rushing defense. They rank in the middle of the pack when you break down yards per carry in certain gaps. It surprised me to see these stats. This is where I think the Saints can take advantage of the Panthers defense.

If the Saints commit to the run early on and continue throughout the game, they will eventually wear down the Panthers defensive line. The Saints offensive line is built with some big boys who can matchup physically with the Panthers stout defensive front.

Running the ball opens up the play-action pass, and Drew Brees has the seventh-best passer rating in the NFL on play action. While that has not been the offense’s bread and butter, against the Panthers, it will be a must. If you allow Kuechly and Thomas Davis to roam free into zone coverages, it will disrupt the passing game.

Have the Panthers settled on an offensive identity?

The reason why I can’t ever fully commit to the Panthers as Super Bowl contenders is because their offense is so up and down, and it starts with Cam Newton. Week to week, we have no idea what Cam we might see.

Going back to their Week 3 matchup, Cam Newton and the Panthers didn’t have an identity. The Panthers offense was still trying to figure things out and Cam Newton wasn’t using his legs.

Here was Saints defensive lineman Cam Jordan after that game: “Clearly he's trying to be more of a pocket passer, and I'm OK with it. Perfectly fine with it.”

Now, Cam is back to using his legs, which had to happen. This sets up a different game on Sunday. However, Cam is still a quarterback and that requires throwing forward passes. He ranks among the bottom half of passer in many statistical categories, like passer rating, yards per game, and completion percentage. Coupled with what was uncharacteristically poor rushing attack through the first eight weeks of the season — it’s gotten better in their last three games — I don’t know what to expect from the Panthers week to week.

The Saints defense will succeed this weekend if likely Defensive Rookie of the Year Marshon Lattimore is back on the field. According to Pro Football Focus, Lattimore is allowing a passer rating of 47 when targeted. He’s been a lockdown corner. If he’s playing, he’ll see a lot of Devin Funchess, who’s play has improved since the Panthers traded away Kelvin Benjamin, almost doubling his yards per game.

I like Lattimore in this matchup. Having a lockdown corner allows the Saints to pressure more often and allows someone to spy on Cam. Both of these are needed when facing the Panthers. Last weekend, the Jets had some success using their pressure package against the Panthers.

If Lattimore plays, the Saints win by 10. If Lattimore is out, I still think the Saints will win it, but it’ll be a close game. I trust the Saints more in this huge division game at home in the dome!

0 notes