#his priories are conflicted because he genuinely cares about ALL of his relationships

Text

The most upsetting part of this scene (and probably the whole ep) are these two looks:

Because the look on Jeff’s face? It’s hopeful and trusting. He has just the slightest ghost of a smile when he looks at Alan, he looks like he has full confidence that Alan is going to back him up, continue backing him up like he does at the start of this confrontation.

But the look on Alan’s face? It’s doubt. He looks at Jeff and he thinks maybe and he breaks eye contact, looks away just slightly, drops his gaze, because he wants to trust Jeff and he can see the hope in those eyes, but he’s unsure. And even if he chooses to trust Jeff, he’s team leader, how can he not side with his boys? How can he not support the majority, the boys he’s known the longest, the boys who’ve proven their loyalty to him and each other over years, and offer the resolution that most benefits the most amount of people?

How can he not choose the rational resolution, even if it requires squashing that hard-earned trust?

#this scene hurt a lot 🥲#but it’s also so refreshing to see a character struggle with their priorities the way alan does#in a lot of bls a character would just prioritize their love interest no matter what#having alan feel genuinely torn between his found family and his (eventual) love interest makes him feel like a very real person#his priories are conflicted because he genuinely cares about ALL of his relationships#alanjeff#jeffalan#pit babe#pit babe the series#pit babe meta#thai drama#asian drama#asian lgbtq dramas#thai bl#asian bl#bl drama#*my stuff#can’t believe this show has gotten me back into gifing and making meta#just wanted to ramble about them a bit because I love them

153 notes

·

View notes

Text

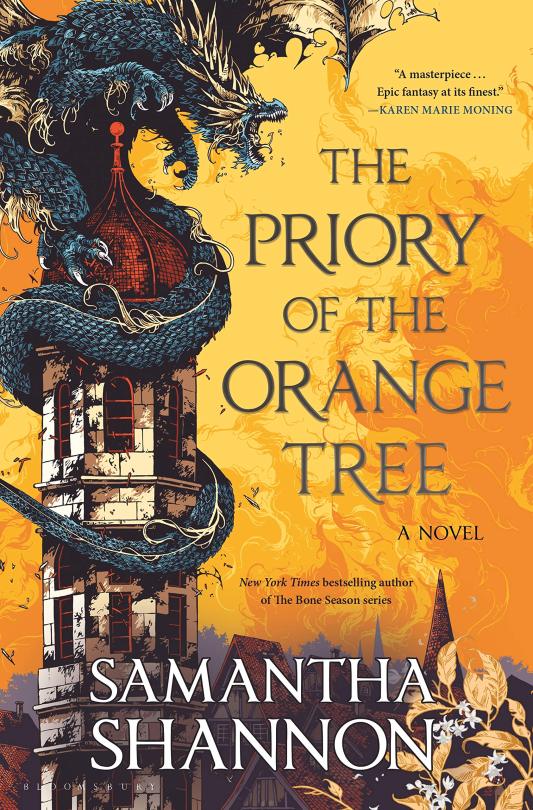

TerraMythos 2021 Reading Challenge - Book 9 of 26

Title: The Priory of the Orange Tree (2019)

Author: Samantha Shannon

Genre/Tags: Fantasy, Epic Fantasy, Third-Person, Female Protagonists, LGBT Protagonists

Rating: 10/10

Date Began: 3/12/2021

Date Finished: 4/12/2021

1000 years ago, the world burned. Draconic creatures terrorized the land, led by a horrific evil known as the Nameless One. But then something happened that sent the monsters into a seemingly endless sleep, and the world has rebuilt in the centuries since.

But the Draconic evil begins to stir in its slumber, and the divided nations of the world have little chance to stop it. Eadaz is a mage from the Priory of the Orange Tree, sent to spy on the northern queendom of Inys. Legend has it that as long as the royal line continues, the world will be free from the Nameless One. While it's a long shot, Ead guards the young Queen Sabran closely to preserve the peace. However, as she and the queen grow closer to each other, Ead has to decide where her loyalties lie. Meanwhile, her close friend Loth is secretly sent into exile by the royal spymaster due to his controversial friendship with the queen. Supposedly sent as an ambassador to the newly Draconic kingdom of Yscalin, he soon finds himself out of his depth, entrusted with a deadly secret.

In the isolationist Eastern country of Seiiki, Tané wants nothing more than to become a dragon rider. The dragons of the East are old, wise, and revered as gods-- eternally opposed to the Draconic legions of the West. However, the night before the choosing ceremony that will decide her fate, she breaks isolation and discovers a young man from the West on the shore. Rather than report him to the authorities, she and her friend smuggle him to the island of Orisima, the only place Westerners are permitted. Niclays Roos, an old man exiled to Orisima by Queen Sabran, soon finds himself caught in the conflict. He believes if he finds an elixir for eternal life, he will finally be able to return home. When he's forced to shelter the forbidden Westerner, Niclays' entire way of life is upended-- but he is soon granted the opportunity to escape his exile.

'My grandmother once said that when a wolf comes to the village, a shepherd looks first to her own flock. The wolf bloods his teeth on other sheep, and the shepherd knows it will one day come for hers, but she clings to the hope that she might be able to keep him out. Until the wolf is at her door.’

Full review, minor spoilers, and content warnings under the cut.

Content warnings for the book: Some sexual content. Blood, gore, violence, traumatic injury, suicide, and death. Torture and execution. Miscarriage. Body horror (kinda). Drug use.

Clocking in at just over 800 pages, The Priory of the Orange Tree is a long, detailed story. I tend to label things Epic Fantasy when they have world-changing stakes. While Priory certainly fits that criteria, it's the first fantasy book I've read in a while that really does feel like an epic. It stars a huge cast of interesting characters from many walks of life, all of whom find themselves caught up in a world-spanning conflict. It captures the sense of a standalone, grand adventure that shorter fantasy novels of today don't typically reach.

With a book this long, it would be easy to ramble on forever about everything I liked. However, I'm going to try to keep it short and simple.

One of my favorite things about this story was the sheer depth of the world. Lots of people compare this to The Lord of the Rings not for its tropes, but the attention to detail regarding the countries, politics, history, religion, and so on. I'm inclined to agree with this assessment. The world felt alive and multi-dimensional. I could pinpoint many parallels to our own mythologies and histories-- particularly drawn from Europe, Asia, and the Middle East. There's also a clear love of language in the story via its beautiful prose. I like to think I know English pretty well, but this book taught me quite a few new words! Might fuck around and call sunsets "rutilant" from now on.

I thought all four leads were interesting. Ead is kinda the "main" lead of the novel, although Tané overtakes her in the latter half. Everyone had different personalities and backstories, and I genuinely enjoyed all of their arcs. Niclays in particular would be an easy character to hate; of the four, he's the most selfish and does some real questionable shit. At the same time, it's hard not to sympathize with him. He's a sad, unjustly exiled elder who's lost the one man he cared about, and finds himself in a desperate situation. These types of characters are interesting to me; a glimpse of what anyone can become given the wrong circumstances and cruel treatment.

With stories like this, one of the most satisfying payoffs is how the different characters and stories come together. It was interesting to see how their paths converged and diverged over time, and ultimately how everything tied together in the end. I also appreciated the character relationships. I liked that Loth's close friendships with both Sabran and Ead were intimate yet platonic without some awkward love triangle.

From some story specifics... I'm a sucker for the bodyguard romance trope, and seeing it done with women in a mainstream novel gave me life. I thought the romance between Ead and Sabran was really sweet; I didn't see how it would work early on since Sabran was a little insufferable, but she had hidden depths (oh god, another weakness of mine). I also really liked the idea of traditional European and Asian dragons being diametrically opposed, and that being a core theme of the story. Intelligent and/or talking animals are another thing I adore in spec fic, so I dug characters like Aralaq. Kalyba's ongoing relevance and gradual exposition was also neat; I love minor world details that turn out super relevant later.

Also, the entire final battle/ending sequence was SO good. Really creative and action packed. Action scenes often blend together for me (and can be logistical nightmares) but Priory's climactic ending was just awesome. I don't want to spoil specifics, but it reminded me of many beloved epic battles in modern fantasy. Avatar the Last Airbender, How To Train Your Dragon, and Pirates of the Caribbean all came to mind.

My main criticism with Priory is that often, the plot relied on convenient coincidence to get the characters out of a jam or otherwise advance the story. I can excuse a minor contrivance or two for the sake of a smooth story, and the scope of this book is big enough that it'd be hard to avoid. But some are nuts. For example, Loth gets rescued from certain death by a giant ichneumon while traveling through the mountains. We later learn the ichneumon is Aralaq, a friend of Ead's, and he just happened to be in the middle of nowhere, far from his home, and stumbled upon Loth. Loth, who ALSO happens to be Ead's best friend... which Aralaq presumably doesn't know?

Another is the MAJOR SPOILER regarding the rising jewel's location. I didn't hate the twist itself, but there was so little build up to it. I wish there were more early hints to justify it, because with setup it would be a pretty cool development. These things didn't ruin my enjoyment of the story, but the borderline deus ex machina (machinae? machinas?) did take me out of it a bit. It’s possible I missed stuff so I’ll give some benefit of the doubt.

Overall, though, The Priory of the Orange Tree is a fun, world-spanning adventure. Like any long book, it's an investment to get into. However, if you're looking for a standalone, feminist fantasy epic, this is certainly a good place to start.

#10/10#taylor reads#2021 reading challenge#bro this took exactly a month to read but in my defense it's long and i also powered through Pillars of Eternity lmfao

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alpha Vs Beta Males: Top 5 Reasons Why Every Man Should Strive To Be An Alpha Male

By Tonyebarcanista

Most people falsely misconstrue Alpha males to be irresponsible men filled with arrogance and are disrespectful towards women. They misconstrue Alpha males with with cocky males.

Many also misconstrue guys that are body builders with nice physique to be alpha males. Some misconstrue wealthy and fierce looking men as alpha males. Some even misconstrue womanizers, famous or people of high status to be alpha males. While some alpha males may belong to the aforementioned groups, not all those groups are alpha males.

Who Is An Alpha Male?

An Alpha male is the real man. He is a man's man and a warrior. He is very confident and a stand-up guy. Irrespective of what you call him, he is a leader. He is the guy others look up to for motivation, inspiration, and often with a hint of jealousy. He is a man that knows what he wants, confident of himself and can't be tossed around. The alpha male knows his power as a man and doesn't use it as tool for oppression. He can't be manipulated by women, and this makes him attracted to women. He's the kind of man every woman want. The Alpha male is mentally and emotionally strong but kind. He is very Confident, yet humble, he assertive, yet gentle at times. He is very powerful, yet calm and tempered. He has self worth yet doesn't proud! He is the kind of man every man should be. He is the kind of man that every woman crave for and hold in high esteem.

Who Is A Beta Male?

Beta males are men that always seek to fit in. They are the typical human pleasers with little or no opinion. Beta males in relationship and marriages are the typical Mr Nice Guys that always bury their thought, desire and want so as not to offend their partners. They are typical followers that always seek to blend with the society. They are not stand alone guys as they are easily manipulated. Because of these traits, Beta males are often disrespected and controlled by their partners, the society, their church, families etcetera.

ALPHA MALES VS BETA MALES

Continue reading after the page break

1. In Relationship

Alpha males go for who and what they want, and are men with standards. When their partners err, they are not afraid to speak their mind, address the problem and speak up when the boundaries they set are crossed. They inform their partners on the effect of their ill informed, they tell their partners the consequences on the relationship and take action to ensure that the partner falls in line. Alpha males don't seek conflicts but are not afraid to tackle conflict head on. They are active and not passive

But Beta males don't have any standard nor boundaries that they hold sacred. They would rather endure and die in silence when their partners err because they are afraid of causing conflict in their relationship. The ones that speak up do so in form of a plea or nag. They are passive men that live with burden in their heart in their bid to maintain peace that they never get.

2. Gentlemen Vs Mr Nice Guys

Alpha males are polite, nice to others, respectful but respects themselves and aren't doormat; Alpha male will never allow anyone treat him like second fiddle no matter what. An Alpha male priories his own well-being, irrespective, he genuinely care about the needs of the people in his life and want the best for others. He does this not do this for validation, to gain attention or to be praised by people around him, he simply does it because it is the right thing to do. When an Alpha male doesn't agree with you, he tells you.

Beta males on the other hand may be nice, courteous etc, but they don't prioritise themselves. They are doormat, Yes-man. They are nice because they need the validation and they agree to a fault because they want to maintain the "Mr Nice Guy" tag.

3. Beta Males Are Bitchy, Alpha males Accepts or Change A Situation:

Alpha males takes responsibility for their lives. Once anything happens in their lives, an Alpha male seeks to do something about it. If an Alpha male finds his partner with another man, he takes action- whether to breakup with her or any other action. An Alpha male makes decision for himself; whether relationship, career or whatever.

But Beta males always look at someone to pass blame on. They don't take responsibility, they bitch over it. A Beta male will find his partner in an unpleasant situation with another man, he runs to his pastor, family or social media to bitch about it... Seeking their help to take action because "he doesn't want to act irrationally". He's a weak man! Simple!!!

4. Genuine Connection Vs validation

An Alpha male always seek genuine connection and friendship with their partners and people around them. They have no time for fake relationship. Alpha males don't seek anybody's validation to feel good. They are true to themselves.

Beta males are pretenders. They desire validation of their partners, friends and society to feel good about themselves. They are fake towards themselves and others around them because they suppress their true feelings for external validation.

5. Alpha males trust themselves to make decisions for their lives, Beta males follow popular opinion.

An alpha male may consult others before making decision, he evaluates the response he gets, and compare with what he had always wanted to do. If he still believe that his desires is the best for him ahead of popular opinion, he follows his mind, makes his decision and swim or sink with it without blaming others.

Beta males consults with people, he may or may not evaluate responses, but he follows popular opinion even if it doesn't tally what he really wants because of his conformist character. He is always ready to blame others should his decision not turn out the way he wishes.

I will stop here!

I remain TonyeBarcanista

Read the full article

0 notes

Text

#775: ‘Ida’, dir. Paweł Pawlikowski, 2013.

Whoa. Okay, no more of this damning with faint praise stuff. This film is good: bleak and somewhat deliberately alienating at times, but also warm and affirming where it counts. I’m not just saying that because it’s short (less than 80 minutes long!) but because I actually, genuinely enjoyed this film in a way that I don’t enjoy a lot of contemporary art cinema.

I mean, it’s a black-and-white film about women coming to terms with the Holocaust, yes. It’s very much a film from the list in that regard. But it’s a compelling look at religious belief and it’s one of the few films I’ve watched recently where it doesn’t feel like the romance plot was there to fulfil some sort of quota. Which is to say, Ida’s attraction to Lis, who plays the saxophone in a band and is pretty damn dreamy and soulful, and how she responds to the conflicting way in which this interacts with the impending solidifying of her faith... no, that’s too complicated. Let’s backtrack.

Ida is a novice nun in the 1960s, living at the priory where she was deposited as an orphan. Before she takes her vows, she is expected to visit her aunt Wanda, her only surviving relative. Wanda is the opposite of Ida in many ways: a garrulous voice of experience, with a fondness for drinking and casual sex that is completely alien to Ida’s understanding of the world. The revelations of Ida’s family history are coupled with Wanda’s increasingly extroverted behaviour: the darker the family’s suffering during the Second World War becomes, the more we see Wanda drinking. Why this is the case becomes clear at about the midpoint, and I don’t want to spoil this development - the film is really that good.

So, it’s a bleak sort of subject matter, but the film injects its second half with a development of Ida’s personality that is both striking and yet totally plausible. When she first meets Lis, he is hitchhiking to a gig, and Ida and Wanda pick him up (there’s a strong road movie dynamic going on through a lot of this). Ida is initially reserved, as a woman who is soon to be a nun should be, but Wanda’s influence on Ida becomes more apparent and eventually the film moves entirely to Ida’s perspective. She and Lis eventually sleep together, but it’s unclear at that point in the film whether this marks a repudiation of her religious faith (which at times seems tenuous) or if this is her way of putting her more worldly thoughts to rest. The film ends with a striking image of Ida walking along a road at dawn. Nothing happens, but it seems that Ida has been shown a lot of the world in a short time, and putting it all to rest is going to be a mammoth, possibly impossible task.

The relationship with Lis is here to develop character, then: both Lis’ and Ida’s, rather than merely being a thing that films are meant to include. I’m not trying to be cynical about that: it’s a perfectly respectable thing to do in your film, even if you’re not making a blockbuster. Many films, even those about niche subjects, have romance plots as standard issue, usually to give a sense of how a character feels by having someone care for them and talk to them about it. In Ida, the romance is more complicated in its purpose, providing not just a development of Ida’s feelings about religion, but also an alternative to it. And that works. It works well.

What makes this film even more visually engaging is the set of decisions Pawlikowski and his crew make. As mentioned, the film is in black and white and, quite oddly, filmed in the 4:3 aspect ratio usually employed for TV productions in the era where TV screens were actually that shape. Pawlikowski’s decisions here hearken back to the moviemaking practices of the 1960s, making the film a relic that draws the audience into a certain era. Even watching on a laptop, opening a DVD file with VLC Media Player, it felt less like witnessing a text from sixty years ago than being in a Polish moviehouse in 1962, watching a contemporary film. Ryszard Lenczewski, one of the film’s cinematographers, has stated that the unusual framing of shots here was designed to “make the audience feel uncertain; to watch in a different way.” Lenczewski doesn’t really elaborate on what ‘different way’ he is referring to, but the unusual style is particularly remarkable, as in this shot:

Ida is full of framings like this. A few people have argued that the ‘golden ratio’ is in a lot of the shots - I don’t think this is an illuminating idea, given that the golden ratio is in everything, but it does speak to the aesthetic intent of a lot of Polish filmmakers. In Ida, characters are usually restricted to the lower half of the frame, and the film overall is filled with expansive skies and shelves and ceilings. At several points in the film, the subtitles gave up completely and moved to whatever dark strip of the frame they could find: in the above shot, the translation of Lis and Ida’s discussion sat in the very centre of the image, lending (perhaps unintentionally) an extra weight to the dialogue.

The film is like this all the way through. Every decision, every revelation, every choice is hovered over constantly by the weight of history and expectation. It could be argued that the God Ida is moving towards embracing is present in every shot, but it could also be the legacy of the Holocaust, acting as a silent witness to Wanda and Ida’s journey, or even the foreboding presence of future terrible events.

Ultimately, I think that’s the point. All of these things are arguably there, depending on what we think Ida is about. That’s why the frame is so wide and so empty: it needs to fit all the ideas into it.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Paley's Natural Theology in Contrast to John Henry Newman

Paley is a natural theologian who died shortly after John Henry Newman was born. His beliefs regarding theology take a rather practical approach in which certain matters of faith are reduced to reason or logic. To him, the external evidence is a large portion for the basis of faith. Newman references him frequently, yet finds fault in his arguments, and is convinced that his proofs are either not sufficient or in some manner irrelevant in regards to most people’s reasons for believing. Rather Newman feels that faith involves a sort acceptance beyond man’s rational faculties that Paley does not acknowledge. For this reason, Newman sees a danger in Paley’s beliefs, for they are not only insufficient for faith, but also misleading. Paley’s practical understanding of faith and reason due to external evidence is in conflict with Newman’s understanding of faith and reason, which is based much less on the evidence for religion.

In order for one to properly understand the relationship between Newman and Paley, one must first understand that Newman does not entirely dismiss Paley as being irrelevant; Newman does admit that there is some usage in his external proofs for faith. Newman finds them to be “consoling.” In his Lecture, Ecclesiastical History No Prejudice to the Apostolicity of the Church he mentions that he has an assortment of shrewd reasoning. 1 That is to say while Newman does not feel that anyone is convinced based on Paley’s proofs nor should they be convinced on Paley’s proofs they do offer a certain bit of stability. A good example would be Paley’s watchmaker theory. If one finds a watch, it is presumable that someone must have made that watch. Paley insists that if a person also finds a rock, it is also presumable for the same reason that someone must have made it as well.2 One can recognize intelligence when he sees it, and to

suppose that something comes from nothing seems somewhat absurd. Newman, does not dismiss this, rather he only suggests that this is not the same as a belief in Christianity. While Paley’s watchmaker analogy is in some ways similar to Aquinas’s proof through causality, Newman still does not feel that this is the most significant matter regarding faith. These kinds of proofs in general are lacking what really inspires one to believe.

The reason there is a difference between Paley and Newman must be first understood in the context that Newman, unlike Paley, is not a natural theologian. Natural theology is known to observe arguments for Christianity from a priori reasoning. Rather than studying what revelation teaches directly( looking at the life of Jesus) natural theology observes the exterior evidences for Christianity using reason and ordinary experience, and then moves towards the interior doctrine. A good example would be looking towards the world around oneself for answers, such as, God exists, as opposed to observing the existence of God by looking at the Bible. The watchmaker analogy fits the same description since it does not depend on revelation or any sort testimony given by Christ. The general approach to natural theology seems to take observations that are distinctly secular regarding the natural world and apply them to Christianity. This is not the approach Newman generally seems to take.

Newman’s critique of Paley’s natural theology is ultimately defined in his approach towards its genus inductive theology. Newman notices that there are three different types of inductive theology including history, revelation, and nature, of which Paley’s natural theology is the one he views with the "greatest suspicion." 3 Inductive theology by its very definition, however, is limited for it moves from particular premises to general conclusions. He finds that inductive theology will find things that only explain partial aspects of Christianity, never regarding Christianity in its entirety. What inductive theology suggests is "a strong probability,

not to a certainty, or again, proving only some things out of the whole number which are true." 4 Newman does not consider this to be the best basis for faith for it depends on every single premise being proven before Christianity can be accepted on a whole. When inductive theology is the approach, one can find himself doubting nearly every aspect in the way Descartes doubted his senses. Newman rather argues that theology is deductive, and that physical science is, "just the reverse," viz. inductive. For one to actually accept Christianity on a basis of particular premises is faulty. There is not enough time for anyone in the world to accept Christianity in this manner for every single premise must first be proven.

Newman considers natural theology to be even more suspect than the other branches of inductive theology because he does not feel that it contributes anything to the Christian faith. While Newman clearly does not have any objection to physicists he does recognize their studies as being separate from that of theology. Natural theology connects theology with nature, but fails to truly prove Christian doctrine with the kind of certainty that it seems to suggest. Rather, Newman states that "it cannot tell us anything of Christianity at all."5 This is because the two have entirely separate ends. Newman noted that

The Physical Philosopher, contemplates the facts before him; the Theologian gives the reasons of these facts. The physicist treats of efficient causes; the Theologian of final. The physicist tells us of laws; the Theologian of the Author, Maintainer, and Controller of them; of their scope, of their suspension, if so be; of their beginning and their end. 6

Newman does not feel that science is a means in order to reach theological truths. For the physical scientist, "a vast and omnigeneous mass of information lies before the inquirer, all in a confused litter, and needing arrangement and analysis." 7 This is not the sort of material that can be used to find truth regarding the trinity. Elsewhere Newman states that: "The material world, indeed, is infinitely more wonderful than any human contrivance; but wonder is not religion, or we should be worshiping our railroads." 8 Here Newman expresses his main disappointment with natural theology

Because natural theology, views theology from outside a Christian revelation, Newman notes that it therefore must also not be original. It is all "pretty much what it was two thousand years ago." 9 Newman makes note when quoting Thomas Macaulay's words that according to Xenophon’s writings Socrates used the exact argument against Aristodemus, as that of Paley’s watchmaker. 10 While Paley may find answers that may suffice in response to certain claims made by atheist, Newman notices that these answers are nothing more than what the Ancient Greeks proposed. While the conclusions they possesses are powerful, good, and wise, they do not possess divine justice, mercy, and providence. Newman considers this approach to be borderline idolatry if it "occupies the mind." 11 Based on these attributes there is very little that would separate the Christian God from the pantheist God.12 Therefore natural theology by not being original is also not Christian, for in order for a doctrine to be Christian it must actually be dependent on some aspect of Christ’s life. Many of Paley’s arguments do not fit this description since they are not actually trying to prove the existence of a Christian reality. He feels the need to separate himself from revelation when arguing. Paley’s description of a watch cannot account for the countless miracles found in revelation. Likewise Paley’s other arguments can also not account for God’s gift of mercy to mankind. Newman does not insist it is heretical to just simply give credit to Paley’s watch theory, only he does not seem to really care if God’s existence has been revealed through the natural world in such a vague manner. While he acknowledges the

truth in Paley’s arguments, he does not allow for it to become the basis for anything distinctly Christian. From observing a rock, one may know there is a creator, but from what Newman seems to be insisting is that while one may know there is a creator, he does not actually know who that Creator is or anything about Him. To omit the later, and be completely content with accepting his existence is to miss the entire point of Christianity. Pagans who worshiped false idols were able to come to similar conclusions. If their conclusions had been enough, then God would have no need to send his Son. Only through Christ and revelation can a person really know who God truly is. What Newman says on behalf of Paley is that Paley almost seems bizarre. “Can alliance more ill-matched and strange be imagined than this, which sheer necessity has brought about, between pseudo-spiritualism and the evidential method?” 13

Newman’s disapproval of Paley’s mentality does not simply just apply to his approach with natural theology. Likewise, Newman also feels that there were certain things amongst faith that just simply cannot be proven. Paley, on the other hand, seems to try to prove everything regarding Christianity. Paley actually seems want to reduce faith to a syllogism. Paley feels that there is no religious love of truth where there is fear of error. For this reason, he insists on proving as many aspects of Christianity he can. Newman, on the contrary maintains that the fear of error is simply necessary for the genuine love of truth. 14 Rather he feels that faith should be an act of the will. While Paley insists that there cannot be love without doubt, Newman actually suggests that doubt is part of faith. Otherwise there is no merit to believing in a certain matter. When a man trusts his friend it is viewed as a virtuous action, or at least a sign of a good friendship. Nothing is different when regarding Christ as one’s friend. One must actually accept Him as their friend,

and trust in His mercy. Doubt is there in order for us to overcome its deceptive abilities. To Paley to believe without a concrete law like process for determining matters of faith is unethical for it is against one’s conscience. However, there does not seem to be a concrete law like process that can be applied to faith without having it lose its merits.

Because Paley is looking for proofs regarding faith, he feels there has to be a logical basis for everything. For this reason Paley feels entitled to Revelation based on his own observation that man needs it. While Paley knows there is a God it would only make sense that He would reveal Himself to mankind in some manner or another. 15 His arguments is that God would acknowledge man’s state of being and thus show himself obligingly. How can person be expected to believe in God if God does not even reveal Himself? This is Paley’s justification for revelation, saying he could expect no less from a divine being, but Newman, however, does not feel quite as deserving. Rather to him revelation is to be considered a gift. God could have left everyone in ignorance like the lives of many individuals. Newman feels that Paley was ungrateful in this regard. Who is man to say that he deserves revelation, or that it is only reasonable that God would do such? God’s ways have never been reasonable by man’s standards. Likewise, people simply sit a home judging evidence based on what they hear making no effort to go and find out the truth for themselves. They make judgments regardless of their own laziness and constantly demand more evidence. What God’s Revelation is is a gift at man’s own convenience. People should not view it as something that’s just simply evidence; rather it is God making Himself known to us. For people not to appreciate this is obscene. 16

Within revelation Newman also found fault in the way that Paley dismissed certain important aspects of the Christian faith. Newman most dominantly did not think that Paley rested

enough of his proofs based on the life of Christ itself. Newman states in his Discussions and Arguments “Paley, for instance—show their sense of this difficulty when they place the argument drawn from the Lord's character only among the auxiliary Evidences of Christianity.” 17 To Newman the way in which Christ lived was much more significant than that of the external evidence that Paley dealt with. The way in which a man lives his life may be the best sign that what he says is correct. Charismatic leaders are often followed for exactly this reason. What they state is just easier to believe, and when you have a character that is as morally upright as Christ was, very little can be said against believing what he states. 18 His wisdom speaks for itself. The arguments made by Paley, Newman could only view as a transitional views. Real faith is found in Christ himself. Paley’s external evidences did not give a man any real reason to believe in Christ. Newman noted that most men agree with the reasoning, however they disagree with the premises. 19

When observing Revelation, Newman and Paley would disagree on their stance regarding miracles, though they do agree with the basic evidence for miracles. A miracle according to Newman is an event that is inconsistent with the natural order or constitution of nature. Paley would agree upon this for he stated that to expect a miracle, “that it should succeed upon a repetition, is to expect that which would make it cease to be a miracle, which is contrary to its nature as such, and would totally destroy the use and purpose for which it was wrought.” 20 A miracle must actually be distinct. Newman did insist that miracles are a matter of evidence. People rely on the evidence for miracles in the same way people rely on the evidence for any

other historical account since they depend on a testimony. Due to the extraordinary nature of miracles a fuller investigation is needed, but the basic principal for miracles is testimony. In the description given in Newman’s sermon on Faith and Reason, contrasted as Habits of Mind21 Paley mentions that matters of faith such as miracles just merely have to be considered not violently improbable in order to be believed. This is where Newman and Paley would differ most strongly, for a miracle can not be judged in the same manner as any other occurrence. Newman would disagree with Paley for he does not think that the evidence can be believed in such a manner. Paley actually mentions judging miracles in the manner in which one would judge a court case or some other matter that was up for debate. While Newman does mention that one should judge a miracle as either true or false based on the testimony, he sees a huge problem in supposing that it could convince someone already held against them. Newman agreed with the statement “miracles are not wrought to convince Atheists,” while Paley seemed to think the exact opposite. In response to Paley he stated

This acute and ingenious writer here asks leave to do only what the Utilitarian writer mentioned in a former place demands should be done, namely, to bring his case (as it were) into court; as if trusting to the strength of his evidence, dispensing with moral and religious considerations on one side or the other, and arguing from the mere phenomena of the human mind, that is, the inducements, motives, and habits according to which man acts. I will not say more of such a procedure than that it seems to me dangerous. 22

Newman notices that there is a rather subjective tone to Paley’s argument. While Paley claims that a court would be an objective place to view a miracle, the exact opposite would occur. In the case of a court house the evidence for miracles would be placed in the hands of a Judge and Jury to decide whether or not it is legitimate. This approach rather only subjects miracles to the same treatment as anything else in a way that actually degrades what they are. Some may be

persuaded while others would dismiss it given the exact same evidence. 23Likewise Paley would also seem to argue that miracles are evidence for religion in so far as that when they occur that atheist should be converted based on testimony. It seems while Paley and Newman may both agree that a miracle should be believed on the basis of testimony the result of such a miracle should be convincing to two different types of people. Neither argues in the way Hume would since Paley states that in order for a Miracle to be consistent it would cease to be a miracle. Newman would insist that miracles are to encourage the faithful, while Paley would seem to insist that miracles are to convince the atheist.

Newman notes that while Paley uses miracles to supposedly argue on behalf of faith, the early apostles never used such in order to persuade anyone. 24 Paley was aware of the fact the early apostles did not use such arguments to try to convince people, yet he did not truly understand why. Paley felt that since the minds of people in times of apostles were so indulged in expressions of magic, it must not have been particularly convincing, therefore they chose not to do such on practical grounds. After all, there were other magicians at the time. Therefore Paley presumed they must have used other methods, not because they were superior, but more appropriate for the time period.

It was their lot to contend with notions of magical agency, against which the mere production of the facts was not sufficient for the convincing of their adversaries; I do not know whether they themselves thought it quite decisive of the controversy. 25

Newman however insisted that the apostles did not try to persuade people through argument. The Apostles were not void of reason, yet the tried to persuade people through their hearts. 26 They used arguments, but on behalf of something that was beyond argument. They appealed to miracles, as signs of divine power, but the method of Paley, as Paley, Newman, and the Bible testifies was not the method on

the Apostles. 27 Rather than accept that his approach was perhaps inappropriate, Paley just simply acknowledges that the Apostles did not use these particular arguments and continues to insist that Miracles are proofs that must be used.

But since it is proved, I conceive with certainty, that the sparingness with which they appealed to miracles was owing neither to their ignorance nor their doubt of the facts, it is at any rate an objection, not to the truth of the history, but to the judgment of its defenders. 28

Newman noted fault with this for the early church leaders in his mind as an Anglican also did not need a pope or plenty of the other arguments placed before them.

One point in which Paley and Newman seem to mostly agree upon however is the appeal to history. Here Paley did not act as natural theologian, but just merely as an inductive theologian. While Newman was critical of all inductive theology he agreed with Paley to an extent on this matter. Newman agrees with Paley in regards to testimony and notes his difficulty in regards to a need to prove testimony. How can a person assert that what Christ says is true, if he cannot even assert that Gospels are a reliable source? Here Paley notes that if a person omits one, there are still three other gospels and plenty of epistles that affirm the same thing. Likewise, Newman also insists that because there are no other claims regarding different events in Christ’s life, the testimony seems to be in favor of the accounts given by Mathew, Mark, Luke and John. The main argument made was that there are no conflicting testimonies to the ones given in which we are to believe the ones handed down. The various authors of the Bible are not inconsistent in their depiction of Christ like Xenophanes and Plato’s depiction of Socrates. This seems logical as even those that were not Christian, such as Piley, seemed to confirm exactly what Christianity taught by their statements. 29 Paley affirms the exact idental notices of the affair, which are found in heathen writers, so far as they do go, go along with us."30

There does however appear to be a difference in the tone of Newman’s arguments for faith then Paley’s. This is because Newman views Christianity before he views individual testimonies. While Paley does not seem to contrast with Newman’s opinion, as an inductive theologian, Paley seems to approach each individual testimony and use them to support the Bible on a whole. When prophets spoke they revealed new information but it was not as though their revelation could make sense without context. “Admiration of its singular simplicity and directness, both as to object and work. Such of course ought to be its character, if it was to be the fulfillment of the ancient, long-expected promise; and such it was, as our Lord proclaimed it.” This seems to be what Paley does, while Newman tries to consider history on a whole.31

Newman observing Paley decades later feels that Paley was not really a Christian Apologist. While Newman does acknowledge what Paley proves, he finds the results inconclusive. There is little no use proving that God exists if God is merely the God pantheism or deism. Unfortunately this was Paley’s arguments from Natural Theology. In regards to historical and revelation, Newman simple thought that Paley as Inductive Theologian viewed it backwards. Rather than trying to Prove Christianity in several pieces, then come to the conclusion that Christianity is real, one must first accept that Christianity is real and argue for it from that perspective. Paley omits what Newman considers to be most crucial in regards to the testimony of Christianity. This would matters such as the incredibly virtuous lie of Christ or the sheer amazement of Revelation. While Newman’s argument is very intelligent, it can be reduced to a very humble, unscientific, simple expression of belief.

0 notes