#ernestine hunt cotton

Text

I can’t say that I really enjoyed Juliet Gardiner’s book Wartime: Britain 1939-1945, which I read a couple of years ago. Particularly coming right after Norman Longmate’s How We Lived Then, it left a sour taste in my mouth. (In a nutshell: Longmate, a veteran of the war, wrote a book about courage and sacrifice; Gardiner, born a few weeks after V-E Day, wrote one about fear and suffering.)

However, Gardiner does introduce the reader to several eyewitnesses to the war about whom I immediately wanted to know more, particularly an American expatriate who when the war broke out was living with her family in an apartment in St. John’s Wood, London. Gardiner, who refers to this woman as Margaret Cotton, quotes several times from her wartime journal. She really could write. A litany-like summary of the damage caused by a V-2 attack is particularly powerful:

The act of destruction and death took a few seconds.

The rescue of victims took a few days.

The billeting of the homeless will take a few weeks.

The healing of the injured will take an indefinite time.

The clearing of the bombed and burned site will take months.

The rebuilding will take years.

The dead are dead.

In her back-matter Gardiner credits these excerpts to an Imperial War Museums file with the assigned title Private Papers of Mrs E H Cotton. (”Mrs,” let’s remember, has traditionally meant “the wife of,” so I simply assumed that those were her husband’s initials.) Since my chances of being able to examine those papers - Mrs. Cotton’s wartime journal, and an apparently unpublished memoir derived from it - any time soon are just about nil, I decided to see whether I could find any more excerpts online. Searching for <”margaret cotton”> didn’t turn anything up, but <“mrs e h cotton”> led me to several books published since 2000. Some of what I found there has turned out to be false: it turns out that she was neither married to a British businessman nor “a young mother at the time of the war,” as certain self-described historians would have it. And one book asserted that her name was Ernestine - not Margaret. Hmm.

Somewhere, I picked up the information that Mrs. Cotton wrote the memoir for the benefit of her grand-daughter, whose name was Penelope. So I searched for <penelope cotton> (not as a phrase) and, to my great surprise, hit the jackpot.

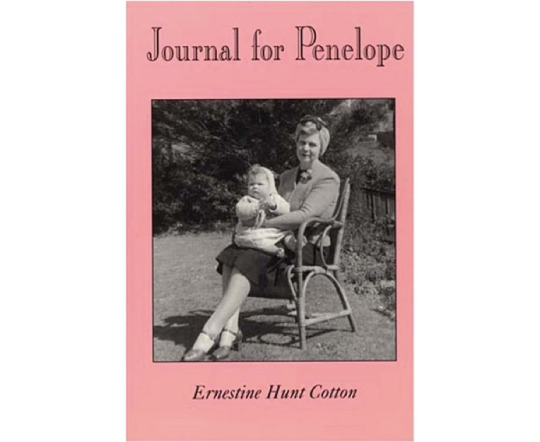

Cotton, Ernestine Hunt.1 Journal for Penelope. New York: Vantage Press, 2005.

Ernestine Hunt Cotton - nicknamed Peg, which may explain Gardiner’s confusion - and her husband, Dick, both Mayflower descendants,2 relocated from the suburbs of Boston to London during the winter of 1934-35, when he became the managing director of British Rola, an offshoot of an American electronics manufacturer. When the war began they had two daughters in their twenties, Alix and Martha, and an adolescent son, Gerry. Alix was engaged to a Fleet Air Arm pilot; as commonly happened during the war, the wedding took place earlier than originally planned, and it gives very little away to say that Alix soon found herself a widow with a small child. Martha was training as a speech pathologist, possibly after a year in medical school. (Mrs. Cotton doesn’t make this clear, and may have conflated the two.) Regardless, Martha had to give up her studies in 1940 when her training school closed for the duration. She joined the British Red Cross.

Mrs. Cotton writes that the family’s move came about as a result of the Depression, but I am skeptical. The Cottons were clearly very well-off: Gerry attended La Châtaigneraie, near Geneva, before the war; when this became impractical he was sent instead to Bryanston, in Dorset. The growing unavailability of household help during the war - the Cottons were accustomed to employing a cook, a housekeeper, and a maid - was a recurring problem. For the last year or so of the war they had homes in both city and country. All of this, along with Martha’s post-secondary studies, whatever they were, had to be paid for somehow.

No, my hunch is that Dick Cotton was doing some sort of classified government service. His initial mandate at British Rola seems to have been to shift its output from loudspeakers and make it “a main artery for pumping life blood into the R.A.F. - literally, for the factory produces a certain type of mechanical pump, built into the planes,” Mrs. Cotton wrote in 1940. Throughout the war he dealt with people at very high levels of the war effort, in both the U.K. and the U.S. He made several return trips during the war, sometimes traveling under very difficult conditions and spending a good deal of time in Washington, D.C., and was one of the organizers of The American Committee for the Defense of British Homes, which donated weapons to the Home Guard. He also appears to have been aware of the existence of the V-weapons, and of precisely how dangerous they would be, several months before they came into use. At one point his wife writes of him talking “in the usual cryptic way of men nowadays - men who are doing a job a bit on the hush-hush.”

In any case, the British Rola factory was located in Acton until October 1940, when severe bombing in that area led the Ministry of Defence to approve (in the form of an order, mind you) its immediate evacuation to a pre-selected site in Bideford, Devon. The entire Cotton family followed suit, and the memoir becomes in part a story of adjustment to country life. With some difficulty, they found a place to live in Instow, three miles from Bideford: Springfield, a nine-bedroom Georgian mansion in a questionable state of repair. While they lived there, the house became a center of hospitality for Allied service personnel generally and, beginning in 1942, for Americans in particular. (At one point the household realize with alarm that they’re sheltering some AWOL sergeants.)

Mostly, though, this book is about the day-to-dayness of the war as it affected one family whose circumstances were a tad unusual. It is clearly the memoir part of the IWM’s papers, and the only clue as to when Mrs. Cotton wrote it is her observation that

This type of fog - a “pea-souper” - is now practically non-existent in London. New buildings have central heating, and there is a law prohibiting the use of any coal save that which has been rendered almost smokeless.

Some passages seem to be lifted directly from the wartime journal, so that we get dizzying transitions between events in progress and those that have occurred some time in the past. And Mrs. Cotton herself can be a bit dizzy at times. After leaving Bryanston, Gerry made multiple attempts to join first the American and then the British armed forces, but was foiled by his susceptibility to what his mother persists in referring to as “anti-philatic shock.” I can only assume that she means anaphylactic shock. (Gerry ended up on the assembly line at British Rola; Alix was a V.A.D. at Bideford Hospital.)

There is also the matter of the book’s production. Vantage Press, which went out of business in 2012, was one of the original vanity publishing operations. Authors’ typescripts - this one was created with word-processing software that was already out-of-date in 2005, and was apparently produced on a dot-matrix printer - were treated as camera-ready copy and were not subjected to any editing whatsoever. The result in this case is a book riddled with typographical errors. The substitution of it’s for the possessive its is so consistent that it becomes annoying all by itself.

Journal for Penelope is nevertheless worth reading. A Republican (of an era long before ours) married to a Democrat, deeply generous in her impulses, a mistress of the vivid simile (”My stomach curled up like a caterpillar”), Ernestine Cotton is very good company. I’d still like to read the original journal - something tells me there’s a good miniseries lurking there! - but this book is an acceptable, and welcome, substitute.

1For anyone unfamiliar with this usage, which as far as I know is purely North American and which seems to be fading away, Mrs. Cotton took her husband’s surname while using her maiden name as a middle (second) name to be included or not as the occasion required. My mother did the same thing; likewise Mercy Otis Warren, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Florence Prag Kahn, Oveta Culp Hobby, Marian Wright Edelman, Hillary Rodham Clinton, Katharine Jefferts Schori, and many others.

2The Mayflower was the first ship to bring non-Native settlers to the region now known as New England, arriving from Plymouth in November 1620. Stereotypically at least, descendants of its passengers are wealthy, entitled, clannish, repressed, highly conscious of their status, and found primarily on the Atlantic seaboard.

#world war II#u.k. home front#american civilians in britain#memoirs#ernestine hunt cotton#a long post for the weekend

4 notes

·

View notes