#confederation of the Rhine

Photo

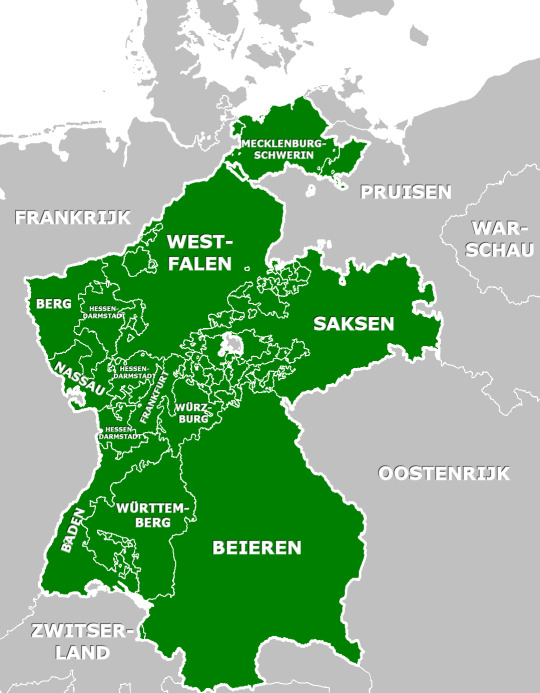

Map of The Confederation of The Rhine.

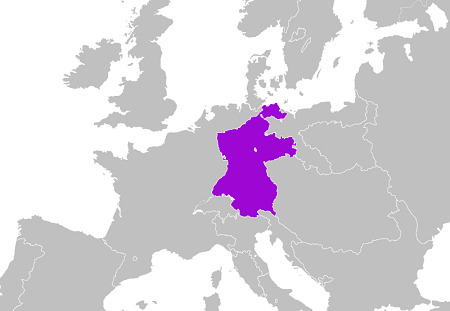

The Confederation of the Rhine was a client state of First French Empire. It existed from 1806 through 1813. Its ruler was Napoleon I of France, called "Protector of the Federation".

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

The introduction of the Napoleonic Code in Bavaria

Probably the best codification work of the Rhine Confederation period was the draft of a "General Civil Code for the Kingdom of Bavaria" from 1808/09, which was essentially based on the suggestions of Paul Johann Anselm von Feuerbach. By starting codification work, the Bavarian King Maximilian IV wanted to give in to Napoleon's urging to introduce his code in Bavaria as well. In a report for the Ministry of Justice in 1808 "on the manner of introducing the Code Napoleon in a German country", Feuerbach highlighted the main ideas of the Code Napoleon: freedom of the person; legal equality of subjects; equality of laws for all citizens of the state ; Freedom of property as well as independence and independence of the state from the church in all civil matters. For him, the Napoleonic Code was a result of the French Revolution: "It was the purpose of French legislation, on the one hand, to completely end the Revolution, on the other, to perpetuate the beneficial results of the Revolution".

Anyone who wants to destroy the basic ideas of a code of law through modification kills “the truly spiritual life of it and turns the living body into a corpse. In the modification retort, on which the inconvenient spiritus rector was supposed to evaporate, nothing more than a caput mortuum would ultimately remain, which would hardly be worth keeping. Precisely those parts of French legislation which contradict our existing German principles are its brightest points." When the discussions of the draft in the Privy Council were almost completed, the conservative aristocratic opposition brought down the proposal in 1809/10. Particularly because of the changes to mortgage law proposed by Feuerbach, the Bavarian draft represents a German version of the Napoleonic Code that is quite equal to the French original. Feuerbach paid particular attention to the linguistic version: insofar as a regulation of the Napoleonic Code should be retained, he was concerned with translating the French original into a "pure German legal language, not tainted by any provincialisms, possibly with the same advantages." However, this should not obscure the fact that the Commission has often exceeded the limits of mere translation. The most important change was that almost all traces of the French judicial constitution were erased from the draft. Article 530 of the Code Napoléon was also modified so that the replacement of perpetual basic pensions should only be permitted with the consent of both parties. The inheritance law was based on the succession order of Austrian law. The property law, which was almost completely ignored by the Napoleonic Code, was regulated in a separate chapter.

Source: Werner Schubert, Der Code civil (Code Napoléon) in Deutschland und das Reichsgericht

[Bold italics by me]

#Paul Johann Anselm von Feuerbach#Feuerbach#napoleon#napoleonic era#king Maximilian I#king Maximilian iv#napoleon bonaparte#napoleonic#first french empire#french empire#19th century#Bavaria#Germany#history#napoleonic code#Napoleon’s reforms#confederation of the Rhine#Rhine confederation#1800s#french revolution#Revolution#napoleonic wars#Werner Schubert#civil code#code civil#law#reforms#laws#civil law#napoleonic reforms

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

1806-Confederation of the Rhine

At the insistence of Napoleon, Bavaria, Baden, Württemberg and thirteen minor principalities leave the Holy Roman Empire and form the Confederation of the Rhine.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

sorry for the rant but redditors are the natural ennemy of historians

they love anachronism they say they were "borders" or "flags" in a time an place where that concept didn't exist (or at the very least not as the way we think of it today) and then they go to wikipedia and upload it and create a new historical misconceptions wich will live forever in some form or the other in the minds of other armchairs historians

#they do this because they are only interested in military history btw#this is about the confederation of the rhine flag

0 notes

Text

Napoleon the Great :: Andrew Roberts

View On WordPress

#978-1-8461-4027-3#austerlitz#battle borodino#battle marengo#books by andrew roberts#brumaire#campaign#confederation rhine#elba#emperors france#first french empire#french emperor#french emperors#french history#french kings#french rulers#french statesmen#history france#marengo#napoleon i#napoleonic france#napoleonic wars#polish campaigns#st helena#syrian campaigns#waterloo

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Great confederation of the Rhine

This is the age of the great confederation of the Rhine, and the rise of the Hanseatic League; for in Germany and in Flanders, where the towns could not count on the protection of a friendly and central monarchy, the towns formed mutual leagues for protection and support amongst themselves. It would need a volume to work out this complex development. But we may take it that, for Northern Europe, the thirteenth century is the era of the definite establishment of rich, free, self-governing municipalities. It is the flourishing era of town charters, of city leagues, and of the systematic establishment of a European commerce, north of the Mediterranean, both inter-provincial and inter-national.

And out of these rich and teeming cities arose that social power destined to such a striking career in the next six centuries — the middle class, a new order in the State, whose importance rests on wealth, intelligence, and organisation, not on birth or on arms. And out of that middle class rose popular representation, election by the commons, i.e., by communes, or corporate constituencies, the third estate. The history of popular representation in Europe would occupy a volume, or many volumes: its conception, birth, and youth fall within the thirteenth century sofia daily tours.

The Great Charter

The Great Charter, which the barons, as real representatives of the whole nation, wrested from John in 1215, did not, it is true, contain any scheme of popular representation; but it asserted the principle, and it laid down canons of public law which led directly to popular representation and a parliamentary constitution. The Great Charter has been talked about for many centuries in vague superlatives of praise, by those who had little precise or accurate knowledge of it. But now that our knowledge of it is full and exact, we see that its importance was in no way exaggerated, and perhaps was hardly understood; and we find it hard adequately to express our admiration of its wise, just, and momentous policy. The Great Charter of 1215 led in a direct line to the complete and developed Parliament of 1295.

And Bishop Stubbs has well named the interval between the two, the eighty years of struggle for a political constitution. The Charter of John contains the principle of taxation through the common council of the realm. From the very first year after it representative councils appear; first from counties; then, in 1254, we have a regular Parliament from shires; in 1264, after the battle of Lewes, Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester, summoned two discreet representatives from towns and cities by writ; in 1273, Edward 1. summoned what was in effect a Parliament; and, after several Parliaments summoned in intervening years, we have the first complete and finally constituted Parliament in 1295.

But our own, the greatest and most permanent of Parliaments, was by no means the earliest. Representatives of cities and boroughs had come to the Cortes of Castile and of Arragon in the twelfth century; early in the thirteenth century Frederick 11. summoned them to general courts in Sicily; in the middle of the century the towns sent deputies to the German Diets; in 1277, the commons and towns swear fealty to Rudolph of Hapsburg; in 1291, was founded in the mountains of Schwytz that Swiss confederation which has just celebrated its 600th anniversary; and, in 1302, Philip the Fair summoned the States-General to back him in his desperate duel with Boniface vm. Thus, seven years after Edward 1. had called to Westminster that first true Parliament which has had there so great a history over 600 years, Philip called together to Notre Dame at Paris the three estates — the clergy, the baronage, and the commons. So clear is it that the thirteenth century called into being that momentous element of modern civilisation, the representation of the people in Parliament.

0 notes

Photo

Great confederation of the Rhine

This is the age of the great confederation of the Rhine, and the rise of the Hanseatic League; for in Germany and in Flanders, where the towns could not count on the protection of a friendly and central monarchy, the towns formed mutual leagues for protection and support amongst themselves. It would need a volume to work out this complex development. But we may take it that, for Northern Europe, the thirteenth century is the era of the definite establishment of rich, free, self-governing municipalities. It is the flourishing era of town charters, of city leagues, and of the systematic establishment of a European commerce, north of the Mediterranean, both inter-provincial and inter-national.

And out of these rich and teeming cities arose that social power destined to such a striking career in the next six centuries — the middle class, a new order in the State, whose importance rests on wealth, intelligence, and organisation, not on birth or on arms. And out of that middle class rose popular representation, election by the commons, i.e., by communes, or corporate constituencies, the third estate. The history of popular representation in Europe would occupy a volume, or many volumes: its conception, birth, and youth fall within the thirteenth century sofia daily tours.

The Great Charter

The Great Charter, which the barons, as real representatives of the whole nation, wrested from John in 1215, did not, it is true, contain any scheme of popular representation; but it asserted the principle, and it laid down canons of public law which led directly to popular representation and a parliamentary constitution. The Great Charter has been talked about for many centuries in vague superlatives of praise, by those who had little precise or accurate knowledge of it. But now that our knowledge of it is full and exact, we see that its importance was in no way exaggerated, and perhaps was hardly understood; and we find it hard adequately to express our admiration of its wise, just, and momentous policy. The Great Charter of 1215 led in a direct line to the complete and developed Parliament of 1295.

And Bishop Stubbs has well named the interval between the two, the eighty years of struggle for a political constitution. The Charter of John contains the principle of taxation through the common council of the realm. From the very first year after it representative councils appear; first from counties; then, in 1254, we have a regular Parliament from shires; in 1264, after the battle of Lewes, Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester, summoned two discreet representatives from towns and cities by writ; in 1273, Edward 1. summoned what was in effect a Parliament; and, after several Parliaments summoned in intervening years, we have the first complete and finally constituted Parliament in 1295.

But our own, the greatest and most permanent of Parliaments, was by no means the earliest. Representatives of cities and boroughs had come to the Cortes of Castile and of Arragon in the twelfth century; early in the thirteenth century Frederick 11. summoned them to general courts in Sicily; in the middle of the century the towns sent deputies to the German Diets; in 1277, the commons and towns swear fealty to Rudolph of Hapsburg; in 1291, was founded in the mountains of Schwytz that Swiss confederation which has just celebrated its 600th anniversary; and, in 1302, Philip the Fair summoned the States-General to back him in his desperate duel with Boniface vm. Thus, seven years after Edward 1. had called to Westminster that first true Parliament which has had there so great a history over 600 years, Philip called together to Notre Dame at Paris the three estates — the clergy, the baronage, and the commons. So clear is it that the thirteenth century called into being that momentous element of modern civilisation, the representation of the people in Parliament.

0 notes

Photo

Great confederation of the Rhine

This is the age of the great confederation of the Rhine, and the rise of the Hanseatic League; for in Germany and in Flanders, where the towns could not count on the protection of a friendly and central monarchy, the towns formed mutual leagues for protection and support amongst themselves. It would need a volume to work out this complex development. But we may take it that, for Northern Europe, the thirteenth century is the era of the definite establishment of rich, free, self-governing municipalities. It is the flourishing era of town charters, of city leagues, and of the systematic establishment of a European commerce, north of the Mediterranean, both inter-provincial and inter-national.

And out of these rich and teeming cities arose that social power destined to such a striking career in the next six centuries — the middle class, a new order in the State, whose importance rests on wealth, intelligence, and organisation, not on birth or on arms. And out of that middle class rose popular representation, election by the commons, i.e., by communes, or corporate constituencies, the third estate. The history of popular representation in Europe would occupy a volume, or many volumes: its conception, birth, and youth fall within the thirteenth century sofia daily tours.

The Great Charter

The Great Charter, which the barons, as real representatives of the whole nation, wrested from John in 1215, did not, it is true, contain any scheme of popular representation; but it asserted the principle, and it laid down canons of public law which led directly to popular representation and a parliamentary constitution. The Great Charter has been talked about for many centuries in vague superlatives of praise, by those who had little precise or accurate knowledge of it. But now that our knowledge of it is full and exact, we see that its importance was in no way exaggerated, and perhaps was hardly understood; and we find it hard adequately to express our admiration of its wise, just, and momentous policy. The Great Charter of 1215 led in a direct line to the complete and developed Parliament of 1295.

And Bishop Stubbs has well named the interval between the two, the eighty years of struggle for a political constitution. The Charter of John contains the principle of taxation through the common council of the realm. From the very first year after it representative councils appear; first from counties; then, in 1254, we have a regular Parliament from shires; in 1264, after the battle of Lewes, Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester, summoned two discreet representatives from towns and cities by writ; in 1273, Edward 1. summoned what was in effect a Parliament; and, after several Parliaments summoned in intervening years, we have the first complete and finally constituted Parliament in 1295.

But our own, the greatest and most permanent of Parliaments, was by no means the earliest. Representatives of cities and boroughs had come to the Cortes of Castile and of Arragon in the twelfth century; early in the thirteenth century Frederick 11. summoned them to general courts in Sicily; in the middle of the century the towns sent deputies to the German Diets; in 1277, the commons and towns swear fealty to Rudolph of Hapsburg; in 1291, was founded in the mountains of Schwytz that Swiss confederation which has just celebrated its 600th anniversary; and, in 1302, Philip the Fair summoned the States-General to back him in his desperate duel with Boniface vm. Thus, seven years after Edward 1. had called to Westminster that first true Parliament which has had there so great a history over 600 years, Philip called together to Notre Dame at Paris the three estates — the clergy, the baronage, and the commons. So clear is it that the thirteenth century called into being that momentous element of modern civilisation, the representation of the people in Parliament.

0 notes

Photo

Great confederation of the Rhine

This is the age of the great confederation of the Rhine, and the rise of the Hanseatic League; for in Germany and in Flanders, where the towns could not count on the protection of a friendly and central monarchy, the towns formed mutual leagues for protection and support amongst themselves. It would need a volume to work out this complex development. But we may take it that, for Northern Europe, the thirteenth century is the era of the definite establishment of rich, free, self-governing municipalities. It is the flourishing era of town charters, of city leagues, and of the systematic establishment of a European commerce, north of the Mediterranean, both inter-provincial and inter-national.

And out of these rich and teeming cities arose that social power destined to such a striking career in the next six centuries — the middle class, a new order in the State, whose importance rests on wealth, intelligence, and organisation, not on birth or on arms. And out of that middle class rose popular representation, election by the commons, i.e., by communes, or corporate constituencies, the third estate. The history of popular representation in Europe would occupy a volume, or many volumes: its conception, birth, and youth fall within the thirteenth century sofia daily tours.

The Great Charter

The Great Charter, which the barons, as real representatives of the whole nation, wrested from John in 1215, did not, it is true, contain any scheme of popular representation; but it asserted the principle, and it laid down canons of public law which led directly to popular representation and a parliamentary constitution. The Great Charter has been talked about for many centuries in vague superlatives of praise, by those who had little precise or accurate knowledge of it. But now that our knowledge of it is full and exact, we see that its importance was in no way exaggerated, and perhaps was hardly understood; and we find it hard adequately to express our admiration of its wise, just, and momentous policy. The Great Charter of 1215 led in a direct line to the complete and developed Parliament of 1295.

And Bishop Stubbs has well named the interval between the two, the eighty years of struggle for a political constitution. The Charter of John contains the principle of taxation through the common council of the realm. From the very first year after it representative councils appear; first from counties; then, in 1254, we have a regular Parliament from shires; in 1264, after the battle of Lewes, Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester, summoned two discreet representatives from towns and cities by writ; in 1273, Edward 1. summoned what was in effect a Parliament; and, after several Parliaments summoned in intervening years, we have the first complete and finally constituted Parliament in 1295.

But our own, the greatest and most permanent of Parliaments, was by no means the earliest. Representatives of cities and boroughs had come to the Cortes of Castile and of Arragon in the twelfth century; early in the thirteenth century Frederick 11. summoned them to general courts in Sicily; in the middle of the century the towns sent deputies to the German Diets; in 1277, the commons and towns swear fealty to Rudolph of Hapsburg; in 1291, was founded in the mountains of Schwytz that Swiss confederation which has just celebrated its 600th anniversary; and, in 1302, Philip the Fair summoned the States-General to back him in his desperate duel with Boniface vm. Thus, seven years after Edward 1. had called to Westminster that first true Parliament which has had there so great a history over 600 years, Philip called together to Notre Dame at Paris the three estates — the clergy, the baronage, and the commons. So clear is it that the thirteenth century called into being that momentous element of modern civilisation, the representation of the people in Parliament.

0 notes

Photo

Great confederation of the Rhine

This is the age of the great confederation of the Rhine, and the rise of the Hanseatic League; for in Germany and in Flanders, where the towns could not count on the protection of a friendly and central monarchy, the towns formed mutual leagues for protection and support amongst themselves. It would need a volume to work out this complex development. But we may take it that, for Northern Europe, the thirteenth century is the era of the definite establishment of rich, free, self-governing municipalities. It is the flourishing era of town charters, of city leagues, and of the systematic establishment of a European commerce, north of the Mediterranean, both inter-provincial and inter-national.

And out of these rich and teeming cities arose that social power destined to such a striking career in the next six centuries — the middle class, a new order in the State, whose importance rests on wealth, intelligence, and organisation, not on birth or on arms. And out of that middle class rose popular representation, election by the commons, i.e., by communes, or corporate constituencies, the third estate. The history of popular representation in Europe would occupy a volume, or many volumes: its conception, birth, and youth fall within the thirteenth century sofia daily tours.

The Great Charter

The Great Charter, which the barons, as real representatives of the whole nation, wrested from John in 1215, did not, it is true, contain any scheme of popular representation; but it asserted the principle, and it laid down canons of public law which led directly to popular representation and a parliamentary constitution. The Great Charter has been talked about for many centuries in vague superlatives of praise, by those who had little precise or accurate knowledge of it. But now that our knowledge of it is full and exact, we see that its importance was in no way exaggerated, and perhaps was hardly understood; and we find it hard adequately to express our admiration of its wise, just, and momentous policy. The Great Charter of 1215 led in a direct line to the complete and developed Parliament of 1295.

And Bishop Stubbs has well named the interval between the two, the eighty years of struggle for a political constitution. The Charter of John contains the principle of taxation through the common council of the realm. From the very first year after it representative councils appear; first from counties; then, in 1254, we have a regular Parliament from shires; in 1264, after the battle of Lewes, Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester, summoned two discreet representatives from towns and cities by writ; in 1273, Edward 1. summoned what was in effect a Parliament; and, after several Parliaments summoned in intervening years, we have the first complete and finally constituted Parliament in 1295.

But our own, the greatest and most permanent of Parliaments, was by no means the earliest. Representatives of cities and boroughs had come to the Cortes of Castile and of Arragon in the twelfth century; early in the thirteenth century Frederick 11. summoned them to general courts in Sicily; in the middle of the century the towns sent deputies to the German Diets; in 1277, the commons and towns swear fealty to Rudolph of Hapsburg; in 1291, was founded in the mountains of Schwytz that Swiss confederation which has just celebrated its 600th anniversary; and, in 1302, Philip the Fair summoned the States-General to back him in his desperate duel with Boniface vm. Thus, seven years after Edward 1. had called to Westminster that first true Parliament which has had there so great a history over 600 years, Philip called together to Notre Dame at Paris the three estates — the clergy, the baronage, and the commons. So clear is it that the thirteenth century called into being that momentous element of modern civilisation, the representation of the people in Parliament.

0 notes

Photo

Great confederation of the Rhine

This is the age of the great confederation of the Rhine, and the rise of the Hanseatic League; for in Germany and in Flanders, where the towns could not count on the protection of a friendly and central monarchy, the towns formed mutual leagues for protection and support amongst themselves. It would need a volume to work out this complex development. But we may take it that, for Northern Europe, the thirteenth century is the era of the definite establishment of rich, free, self-governing municipalities. It is the flourishing era of town charters, of city leagues, and of the systematic establishment of a European commerce, north of the Mediterranean, both inter-provincial and inter-national.

And out of these rich and teeming cities arose that social power destined to such a striking career in the next six centuries — the middle class, a new order in the State, whose importance rests on wealth, intelligence, and organisation, not on birth or on arms. And out of that middle class rose popular representation, election by the commons, i.e., by communes, or corporate constituencies, the third estate. The history of popular representation in Europe would occupy a volume, or many volumes: its conception, birth, and youth fall within the thirteenth century sofia daily tours.

The Great Charter

The Great Charter, which the barons, as real representatives of the whole nation, wrested from John in 1215, did not, it is true, contain any scheme of popular representation; but it asserted the principle, and it laid down canons of public law which led directly to popular representation and a parliamentary constitution. The Great Charter has been talked about for many centuries in vague superlatives of praise, by those who had little precise or accurate knowledge of it. But now that our knowledge of it is full and exact, we see that its importance was in no way exaggerated, and perhaps was hardly understood; and we find it hard adequately to express our admiration of its wise, just, and momentous policy. The Great Charter of 1215 led in a direct line to the complete and developed Parliament of 1295.

And Bishop Stubbs has well named the interval between the two, the eighty years of struggle for a political constitution. The Charter of John contains the principle of taxation through the common council of the realm. From the very first year after it representative councils appear; first from counties; then, in 1254, we have a regular Parliament from shires; in 1264, after the battle of Lewes, Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester, summoned two discreet representatives from towns and cities by writ; in 1273, Edward 1. summoned what was in effect a Parliament; and, after several Parliaments summoned in intervening years, we have the first complete and finally constituted Parliament in 1295.

But our own, the greatest and most permanent of Parliaments, was by no means the earliest. Representatives of cities and boroughs had come to the Cortes of Castile and of Arragon in the twelfth century; early in the thirteenth century Frederick 11. summoned them to general courts in Sicily; in the middle of the century the towns sent deputies to the German Diets; in 1277, the commons and towns swear fealty to Rudolph of Hapsburg; in 1291, was founded in the mountains of Schwytz that Swiss confederation which has just celebrated its 600th anniversary; and, in 1302, Philip the Fair summoned the States-General to back him in his desperate duel with Boniface vm. Thus, seven years after Edward 1. had called to Westminster that first true Parliament which has had there so great a history over 600 years, Philip called together to Notre Dame at Paris the three estates — the clergy, the baronage, and the commons. So clear is it that the thirteenth century called into being that momentous element of modern civilisation, the representation of the people in Parliament.

0 notes

Photo

Great confederation of the Rhine

This is the age of the great confederation of the Rhine, and the rise of the Hanseatic League; for in Germany and in Flanders, where the towns could not count on the protection of a friendly and central monarchy, the towns formed mutual leagues for protection and support amongst themselves. It would need a volume to work out this complex development. But we may take it that, for Northern Europe, the thirteenth century is the era of the definite establishment of rich, free, self-governing municipalities. It is the flourishing era of town charters, of city leagues, and of the systematic establishment of a European commerce, north of the Mediterranean, both inter-provincial and inter-national.

And out of these rich and teeming cities arose that social power destined to such a striking career in the next six centuries — the middle class, a new order in the State, whose importance rests on wealth, intelligence, and organisation, not on birth or on arms. And out of that middle class rose popular representation, election by the commons, i.e., by communes, or corporate constituencies, the third estate. The history of popular representation in Europe would occupy a volume, or many volumes: its conception, birth, and youth fall within the thirteenth century sofia daily tours.

The Great Charter

The Great Charter, which the barons, as real representatives of the whole nation, wrested from John in 1215, did not, it is true, contain any scheme of popular representation; but it asserted the principle, and it laid down canons of public law which led directly to popular representation and a parliamentary constitution. The Great Charter has been talked about for many centuries in vague superlatives of praise, by those who had little precise or accurate knowledge of it. But now that our knowledge of it is full and exact, we see that its importance was in no way exaggerated, and perhaps was hardly understood; and we find it hard adequately to express our admiration of its wise, just, and momentous policy. The Great Charter of 1215 led in a direct line to the complete and developed Parliament of 1295.

And Bishop Stubbs has well named the interval between the two, the eighty years of struggle for a political constitution. The Charter of John contains the principle of taxation through the common council of the realm. From the very first year after it representative councils appear; first from counties; then, in 1254, we have a regular Parliament from shires; in 1264, after the battle of Lewes, Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester, summoned two discreet representatives from towns and cities by writ; in 1273, Edward 1. summoned what was in effect a Parliament; and, after several Parliaments summoned in intervening years, we have the first complete and finally constituted Parliament in 1295.

But our own, the greatest and most permanent of Parliaments, was by no means the earliest. Representatives of cities and boroughs had come to the Cortes of Castile and of Arragon in the twelfth century; early in the thirteenth century Frederick 11. summoned them to general courts in Sicily; in the middle of the century the towns sent deputies to the German Diets; in 1277, the commons and towns swear fealty to Rudolph of Hapsburg; in 1291, was founded in the mountains of Schwytz that Swiss confederation which has just celebrated its 600th anniversary; and, in 1302, Philip the Fair summoned the States-General to back him in his desperate duel with Boniface vm. Thus, seven years after Edward 1. had called to Westminster that first true Parliament which has had there so great a history over 600 years, Philip called together to Notre Dame at Paris the three estates — the clergy, the baronage, and the commons. So clear is it that the thirteenth century called into being that momentous element of modern civilisation, the representation of the people in Parliament.

0 notes

Text

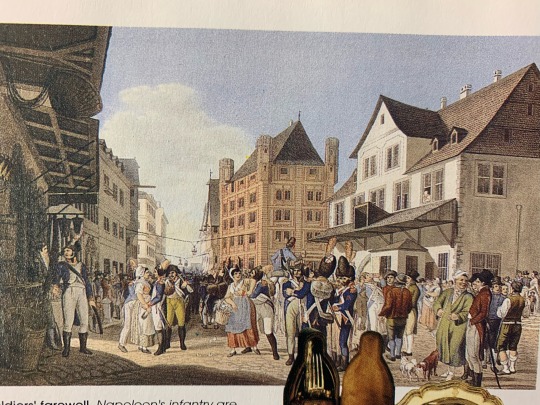

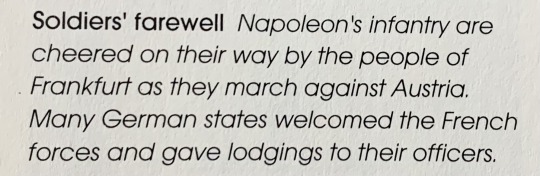

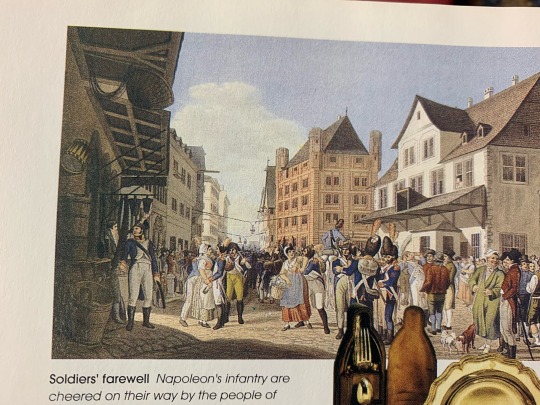

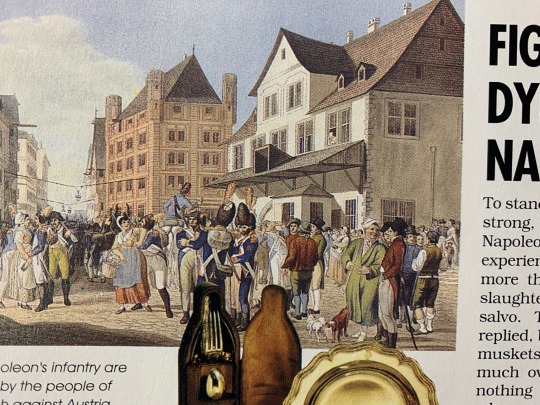

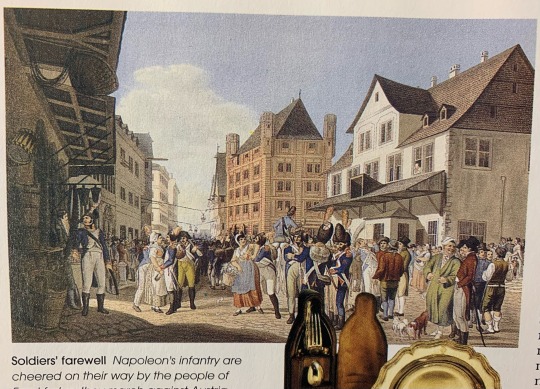

Frankfurt, Germany during the Napoleonic Wars

Source: Everyday Life Through the Ages (Reader's Digest)

#interesting#Frankfurt#napoleonic era#napoleonic#19th century#first french empire#french empire#napoleon#napoleon bonaparte#art#historical art#history#Germany#hre#holy Roman Empire#confederation of the Rhine#france#frev#French Revolution#la révolution française#révolution française#infantry#military uniforms#French history#german history#napoleonic wars#empire#Europe#1800s#early 19th century

34 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Great confederation of the Rhine

This is the age of the great confederation of the Rhine, and the rise of the Hanseatic League; for in Germany and in Flanders, where the towns could not count on the protection of a friendly and central monarchy, the towns formed mutual leagues for protection and support amongst themselves. It would need a volume to work out this complex development. But we may take it that, for Northern Europe, the thirteenth century is the era of the definite establishment of rich, free, self-governing municipalities. It is the flourishing era of town charters, of city leagues, and of the systematic establishment of a European commerce, north of the Mediterranean, both inter-provincial and inter-national.

And out of these rich and teeming cities arose that social power destined to such a striking career in the next six centuries — the middle class, a new order in the State, whose importance rests on wealth, intelligence, and organisation, not on birth or on arms. And out of that middle class rose popular representation, election by the commons, i.e., by communes, or corporate constituencies, the third estate. The history of popular representation in Europe would occupy a volume, or many volumes: its conception, birth, and youth fall within the thirteenth century sofia daily tours.

The Great Charter

The Great Charter, which the barons, as real representatives of the whole nation, wrested from John in 1215, did not, it is true, contain any scheme of popular representation; but it asserted the principle, and it laid down canons of public law which led directly to popular representation and a parliamentary constitution. The Great Charter has been talked about for many centuries in vague superlatives of praise, by those who had little precise or accurate knowledge of it. But now that our knowledge of it is full and exact, we see that its importance was in no way exaggerated, and perhaps was hardly understood; and we find it hard adequately to express our admiration of its wise, just, and momentous policy. The Great Charter of 1215 led in a direct line to the complete and developed Parliament of 1295.

And Bishop Stubbs has well named the interval between the two, the eighty years of struggle for a political constitution. The Charter of John contains the principle of taxation through the common council of the realm. From the very first year after it representative councils appear; first from counties; then, in 1254, we have a regular Parliament from shires; in 1264, after the battle of Lewes, Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester, summoned two discreet representatives from towns and cities by writ; in 1273, Edward 1. summoned what was in effect a Parliament; and, after several Parliaments summoned in intervening years, we have the first complete and finally constituted Parliament in 1295.

But our own, the greatest and most permanent of Parliaments, was by no means the earliest. Representatives of cities and boroughs had come to the Cortes of Castile and of Arragon in the twelfth century; early in the thirteenth century Frederick 11. summoned them to general courts in Sicily; in the middle of the century the towns sent deputies to the German Diets; in 1277, the commons and towns swear fealty to Rudolph of Hapsburg; in 1291, was founded in the mountains of Schwytz that Swiss confederation which has just celebrated its 600th anniversary; and, in 1302, Philip the Fair summoned the States-General to back him in his desperate duel with Boniface vm. Thus, seven years after Edward 1. had called to Westminster that first true Parliament which has had there so great a history over 600 years, Philip called together to Notre Dame at Paris the three estates — the clergy, the baronage, and the commons. So clear is it that the thirteenth century called into being that momentous element of modern civilisation, the representation of the people in Parliament.

0 notes

Photo

Great confederation of the Rhine

This is the age of the great confederation of the Rhine, and the rise of the Hanseatic League; for in Germany and in Flanders, where the towns could not count on the protection of a friendly and central monarchy, the towns formed mutual leagues for protection and support amongst themselves. It would need a volume to work out this complex development. But we may take it that, for Northern Europe, the thirteenth century is the era of the definite establishment of rich, free, self-governing municipalities. It is the flourishing era of town charters, of city leagues, and of the systematic establishment of a European commerce, north of the Mediterranean, both inter-provincial and inter-national.

And out of these rich and teeming cities arose that social power destined to such a striking career in the next six centuries — the middle class, a new order in the State, whose importance rests on wealth, intelligence, and organisation, not on birth or on arms. And out of that middle class rose popular representation, election by the commons, i.e., by communes, or corporate constituencies, the third estate. The history of popular representation in Europe would occupy a volume, or many volumes: its conception, birth, and youth fall within the thirteenth century sofia daily tours.

The Great Charter

The Great Charter, which the barons, as real representatives of the whole nation, wrested from John in 1215, did not, it is true, contain any scheme of popular representation; but it asserted the principle, and it laid down canons of public law which led directly to popular representation and a parliamentary constitution. The Great Charter has been talked about for many centuries in vague superlatives of praise, by those who had little precise or accurate knowledge of it. But now that our knowledge of it is full and exact, we see that its importance was in no way exaggerated, and perhaps was hardly understood; and we find it hard adequately to express our admiration of its wise, just, and momentous policy. The Great Charter of 1215 led in a direct line to the complete and developed Parliament of 1295.

And Bishop Stubbs has well named the interval between the two, the eighty years of struggle for a political constitution. The Charter of John contains the principle of taxation through the common council of the realm. From the very first year after it representative councils appear; first from counties; then, in 1254, we have a regular Parliament from shires; in 1264, after the battle of Lewes, Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester, summoned two discreet representatives from towns and cities by writ; in 1273, Edward 1. summoned what was in effect a Parliament; and, after several Parliaments summoned in intervening years, we have the first complete and finally constituted Parliament in 1295.

But our own, the greatest and most permanent of Parliaments, was by no means the earliest. Representatives of cities and boroughs had come to the Cortes of Castile and of Arragon in the twelfth century; early in the thirteenth century Frederick 11. summoned them to general courts in Sicily; in the middle of the century the towns sent deputies to the German Diets; in 1277, the commons and towns swear fealty to Rudolph of Hapsburg; in 1291, was founded in the mountains of Schwytz that Swiss confederation which has just celebrated its 600th anniversary; and, in 1302, Philip the Fair summoned the States-General to back him in his desperate duel with Boniface vm. Thus, seven years after Edward 1. had called to Westminster that first true Parliament which has had there so great a history over 600 years, Philip called together to Notre Dame at Paris the three estates — the clergy, the baronage, and the commons. So clear is it that the thirteenth century called into being that momentous element of modern civilisation, the representation of the people in Parliament.

0 notes

Photo

Great confederation of the Rhine

This is the age of the great confederation of the Rhine, and the rise of the Hanseatic League; for in Germany and in Flanders, where the towns could not count on the protection of a friendly and central monarchy, the towns formed mutual leagues for protection and support amongst themselves. It would need a volume to work out this complex development. But we may take it that, for Northern Europe, the thirteenth century is the era of the definite establishment of rich, free, self-governing municipalities. It is the flourishing era of town charters, of city leagues, and of the systematic establishment of a European commerce, north of the Mediterranean, both inter-provincial and inter-national.

And out of these rich and teeming cities arose that social power destined to such a striking career in the next six centuries — the middle class, a new order in the State, whose importance rests on wealth, intelligence, and organisation, not on birth or on arms. And out of that middle class rose popular representation, election by the commons, i.e., by communes, or corporate constituencies, the third estate. The history of popular representation in Europe would occupy a volume, or many volumes: its conception, birth, and youth fall within the thirteenth century sofia daily tours.

The Great Charter

The Great Charter, which the barons, as real representatives of the whole nation, wrested from John in 1215, did not, it is true, contain any scheme of popular representation; but it asserted the principle, and it laid down canons of public law which led directly to popular representation and a parliamentary constitution. The Great Charter has been talked about for many centuries in vague superlatives of praise, by those who had little precise or accurate knowledge of it. But now that our knowledge of it is full and exact, we see that its importance was in no way exaggerated, and perhaps was hardly understood; and we find it hard adequately to express our admiration of its wise, just, and momentous policy. The Great Charter of 1215 led in a direct line to the complete and developed Parliament of 1295.

And Bishop Stubbs has well named the interval between the two, the eighty years of struggle for a political constitution. The Charter of John contains the principle of taxation through the common council of the realm. From the very first year after it representative councils appear; first from counties; then, in 1254, we have a regular Parliament from shires; in 1264, after the battle of Lewes, Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester, summoned two discreet representatives from towns and cities by writ; in 1273, Edward 1. summoned what was in effect a Parliament; and, after several Parliaments summoned in intervening years, we have the first complete and finally constituted Parliament in 1295.

But our own, the greatest and most permanent of Parliaments, was by no means the earliest. Representatives of cities and boroughs had come to the Cortes of Castile and of Arragon in the twelfth century; early in the thirteenth century Frederick 11. summoned them to general courts in Sicily; in the middle of the century the towns sent deputies to the German Diets; in 1277, the commons and towns swear fealty to Rudolph of Hapsburg; in 1291, was founded in the mountains of Schwytz that Swiss confederation which has just celebrated its 600th anniversary; and, in 1302, Philip the Fair summoned the States-General to back him in his desperate duel with Boniface vm. Thus, seven years after Edward 1. had called to Westminster that first true Parliament which has had there so great a history over 600 years, Philip called together to Notre Dame at Paris the three estates — the clergy, the baronage, and the commons. So clear is it that the thirteenth century called into being that momentous element of modern civilisation, the representation of the people in Parliament.

0 notes