#cartographyat2700F

Photo

THEATER / 2018-2019

CARTOGRAPHY

STUDENT GUIDE

World premiere Kennedy Center co-commission

Written by Christopher Myers

Directed by Kaneza Schaal

Teacher and Parent Guide: Cartography

“We are in the middle of one of the largest mass migrations in human history.”

—Kaneza Schaal, Cartography director

So, What’s Going On?

Inflatable rafts on the Mediterranean Sea. Dark holds of cargo trucks. Family photos wrapped carefully in a backpack that crosses border checkpoints. Cartography explores how the world is alive with movement and migration as migrants and refugees leave or flee their homes due to war, poverty, and climate change in hopes of a better life. It examines the forces that shape where we have come from, how we have moved, and where we are going.

About the Play

Caption: Photo taken by Christopher Myers at a Cartography workshop in 2017.

Credit: Photo by Christopher Myers

The word “cartography” refers to the science and art of creating maps. It is an ancient practice using symbols to represent places and landscapes to help travelers and others to understand and navigate where they are and where they hope to go. Maps, both physical and conceptual, are a core theme and symbol in the play Cartography.

Cartography asks audiences to examine the history of human migration and plight of refugees. It invites us to relate their stories to our own or those of our families and our past generations. How did we get here? Why do we humans move from one place to another? What are we escaping? Or what are we moving toward?

“It’s such a gift to understand the world as one of migration as opposed to these hot points of tension and trauma,” explained playwright Christopher Myers. “We wanted to use theater to create a point of contact through which people who have experienced this kind of hardship and the people have never experienced this kind of hardship could meet and see each other.”

About the Process

The play took form after the creative team of Christopher Myers and Kaneza Schaal spent time working with young refugees and migrants from around the world. These young people had fled war, persecution, and poverty in search of a better life far from where they were born and spent their early childhoods. Some hiked overland while others arrived in lifeboats, alone or together with family members. In recent years, thousands of refugees are believed to have died in the effort.

The performance of Cartography isn’t based on a playwright’s written script in the traditional sense, nor is it a plot-driven narrative moving toward a climax and resolution. Instead, it is “devised documentary theater.” This style of play is based on factual material including interviews. A group of performers then improvise and experiment with related ideas and scenes. The writer or writers watch and listen for what works and refine it into a script.

For Cartography, this creative process revealed the actual experiences of young people, rendering their stories into short scenes, or vignettes. The play does not center on individual characters. Instead, the performers portray the range of experiences, sharing stories and acting out events.

Talking Terms

World events come at us fast, and often the information we get is incomplete or even distorted. This difficulty includes news reports about migration and refugees. Here is a glossary of key terms that can help you get the most out of Cartography as well as current news coverage.

Migration is a pattern of human or animal movement from one location or habitat to another.

Internal migration is the pattern of movement within one country—from the countryside to the city, for example.

Refugees are persons fleeing armed conflict or persecution, perhaps because of their racial or religious identity. It is often unsafe for them to return home.

Migrants choose to move to improve their lives often by relocating somewhere with more resources or opportunities.

Immigrants are people who move to another place to live. Undocumented immigrants are immigrants who settle in another country without seeking permission.

Asylum is when refugees receive official permission to stay in a country after arriving there.

Visas are official documents that allow visa holders to visit or stay in a foreign country.

Passports are government documents that prove citizenship in a specific country.

ID, short for identification, refers to papers that prove a person’s identity.L

This video explains basic definitions and concepts related to migration. “What Does It Mean to Be a Refugee.?” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=25bwiSikRsI

youtube

The Creative Team

The playwright of Cartography, Christopher Myers, is an award-winning author and illustrator of children’s books. He travels the world, stimulated by his curiosity to experience other cultures and artistic expressions. On his website, he says, “I’ve been asking the question lately, ‘What does it mean to be an artist whose work is rooted in the experience of global cultural exchange?’”

Kaneza Schaal is a theater professional based in New York City, but who has developed creative projects worldwide. She specializes in using collaboration and multimedia to produce theatrical experiences that reflect on the interactions of cultures and the meaning of being human.

Schaal and Myers worked with young refugees and migrants for a month at the International Youth Library in Munich, Germany, and later at New York University Abu Dhabi, in the United Arab Emirates. They listened and brought together stories and insights about the experience and effects of migration. “There was this young man from Syria,” Myers recalls. “I asked him what he wanted me to bring back after speaking and working together. He said, ‘I don’t want to be invisible anymore.’”

This collaboration between youth and artists grew and developed into the play Cartography. For more information about its development, see the Q & A with Christopher Myers in the Adult Guide.

What to Look and Listen for

Cartography does not follow a traditional storyline, with a clear beginning, middle, and end. Instead, it consists of a series of vignettes or scenes that explore the uncertainties and aspirations of young refugees and migrants. With this in mind, check out:

Ways the scenery and props are used to create settings, from life rafts to border walls to waiting rooms.

The production’s simple set design. “I designed it so that it could be packed and moved in a hurry,” Myers says, reflecting one of the challenges faced by people constantly on the move.

How the young refugees treat and think about their possessions, from family photos to cell phones to house keys. (You’ll find a related activity below in the “Take Action” section.)

How the production uses contrasts to create and intensify moods onstage—dark and light, loud and calm, funny and serious.

During the scene in the lifeboat, how the sea behaves depending on the action and sound onstage.

At one point, a character says: “So they want a story? … We may not have much, but we have those.” Listen for how the characters use stories to make sense of what is happening to them.

Their feelings about “home,” both the places they have fled and their hopes for making a new home in a new country.

When the actors are performing as characters, and when they switch to speaking as themselves.

How the characters interact with the audience and use technology to compare and contrast family histories of migration.

Think About This…

At the heart of the play is a core question: What is the meaning of “home”? Answers vary from person to person, yet we share many common experiences across personal history and cultures. To explore this question, it may help to keep the following ideas and inquiries in mind:

Listen to the stories the characters tell, and try to see and describe the emotions, motivations, choices, and actions you observe.

Describe the expectations as well as fears these young people have about starting a new life in a new place, and what they are missing about what they have left behind.

What does “home” mean to you? Is it a house or neighborhood? Your family? List the people, things, and memories that make a place home to you.

What causes people to relocate? Often, there is a combination of “push factors” forcing people to flee a place, and “pull factors” that draw them toward another. What push and pull factors are discussed in the play? What are forces that work against the characters?

As dramatized in the play, migrations are key turning points in the stories and histories of many of our families. Where did you and your family come from—recently and in past generations? (You’ll find a related activity below in the “Take Action” section.)

What do you carry with you that connects you to your home? They can be physical like photos or metaphorical like a song or comfort food from childhood. (You’ll find a related activity below in the “Take Action” section.)

Notice the characters’ attention to “paper” and its importance in Cartography. Why are their papers so important to them?

Maps come in many forms and are used in many ways. What are ways you use maps in your life? How do the characters use maps in the play and what do maps mean to them?

Think of a move or migration you or others have made—short or long-distance—and consider what adjustments were necessary. Did it involve learning new words or languages? Making new friends? Picking up a new set of dos and don’ts? In other words, what are ways that changing places can change people?

Take Action

“My Stuff” Activity

In Cartography, the characters recall the physical objects they brought with them when they left home—from underwear to a Bible to “lemons to fight sea sickness.” What objects are important to you? Tell the story to a friend of a meaningful object in your life or share a photo of it at #KCTYA and #CartographyDC.

Identity Collage

What are the various elements that make you you? Collect images and words/phrases that reflect elements of your identity from magazines, catalogs, and photographs. Cut them out and glue them on card stock or cardboard. Fashion them into a collage that reflects your ideas about your identity. (Small objects like buttons, badges, and decals can also add interesting textures and ideas.)

“How to Make an Archetypal Soul Collage Card.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8rJwUjrwfQ0

youtube

If you prefer working digitally, there are free online apps for collaging, including www.photocollage.com, www.befunky.com, and https://pic-collage.com.

Migration Map

“In the end, we are the sum total of the stories that have come before us,” says Myers. “It’s true of anyone.” For him, one of the stories is a grandfather who arrived from Germany in 1928. What do you know about your family history? Where did your ancestors come from and what are historical family names? What migrations—big or small—brought you to where you live now?

Research your family’s past by talking to parents, grandparents, aunts, and uncles. What are family stories that have been passed from one generation to the next? List meaningful towns, cities, states, and countries where “your people” came from. Plot these places on a blank world map, adding lines that trace your family’s movements to where you call home today.

For a free printout of a world map, see: https://media.nationalgeographic.org/assets/file/world-1pagemap-nolabels.pdf.

Get Your Write On

Writing is an effective way to turn random thoughts into ideas. Try this exercise and see what ideas are floating around in you.

After seeing Cartography, find a quiet time and set five minutes on a timer. Alone or with a partner, write down all the words that watching the play brought to mind, e.g. maps, cell phone, passport, borders, bombs, etc.

Use your word list to inspire an acrostic poem. An acrostic poem is a type of verse where the letters of a key word are featured. Here are two kinds—one with the word’s letter beginning each line, the other where the letters occur within the lines.

We cannot seem to help ourselves,

A burning need to prove we’re right,

Renders peace beyond our grasp.

They are Just words

Yet Our hearts rise

When we Know our humor

Lifts the hEarts of others.

Create an acrostic poem based on the word “home,” and share it at #KCTYA and #CartographyDC.

H

O

M

E

“Acrostic Poem: Examples for Kids.” English Literature Hub. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=acr7nckxO5I

youtube

Go Deeper/Learn More

“‘Refugees’ and ‘Migrants’ – Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs).” What is the difference between a “migrant” and “refugee”? This United Nations Q & A gives clear answers about migration and international law. http://www.unhcr.org/news/latest/2016/3/56e95c676/refugees-migrants-frequently-asked-questions-faqs.html

“Origins and Destinations of the World’s Migrants, 1990–2017.” Pew Research Center. Feb. 28, 2018. This interactive website lets viewers investigate recent migration patterns. http://www.pewglobal.org/2018/02/28/global-migrant-stocks/?country=US&date=2017

Video: “Watch 125,000 years of human migration in 1 minute.” World Economic Forum. Nov. 2, 2016. Think human migration is only a current event? Watch this clip to see how central it is to human history. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/11/watch-125000-years-of-human-migration-in-1-minute/

EXPLORE MORE

Go even deeper with the Cartography Extras.

You’re ready for Cartography.

-

Writer: Sean McCollum

Content Editor: Lisa Resnick

Logistics Coordination: Katherine Huseman

Producer and Program Manager: Tiffany A. Bryant

-

Cartography is part of the Kennedy Center's Human Journey www.kennedy-center.org/humanjourney

The Human Journey is a collaboration between The Kennedy Center, National Geographic Society, and the National Gallery of Art, which invites audiences to investigate the powerful experiences of migration, exploration, identity, and resilience through the lenses of the performing arts, science, and visual art.

David M. Rubenstein

Chairman

Deborah F. Rutter

President

Mario R. Rossero

Senior Vice President

Education

Bank of America is the Presenting Sponsor of Performances for Young Audiences.

Additional support for Cartography is provided by A. James & Alice B. Clark Foundation; the Kimsey Endowment; The Morris and Gwendolyn Cafritz Foundation; Paul M. Angell Family Foundation; and the U.S. Department of Education.

Funding for Access and Accommodation Programs at the Kennedy Center is provided by the U.S. Department of Education.

Major support for educational programs at the Kennedy Center is provided by David M. Rubenstein through the Rubenstein Arts Access Program.

Kennedy Center education and related artistic programming is made possible through the generosity of the National Committee for the Performing Arts.

© 2019 The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts

0 notes

Text

THEATER / 2018-2019

CARTOGRAPHY

TEACHER AND PARENT GUIDE

World premiere Kennedy Center co-commission

Written by Christopher Myers

Directed by Kaneza Schaal

Student Guide: Cartography

Parents, Teachers, and Caregivers: Get the Conversation Going

Human migration is an ongoing theme in human history. Whether the people on the move have been refugees fleeing war or natural disaster, or migrants relocating somewhere they hope will offer greater opportunity, much of humanity’s story has been about people seeking a new home in a new land.

Today’s stories of refugees and migrants are no different. Cartography, written by Christopher Myers and directed by Kaneza Schaal, invites people to make the connection. “I really want young people to see themselves in that context, whether their stories are personal or farther back in their family’s history,” says Myers. (You can find an interview with Myers below.)

For this production, 2700 F St. invites teachers, parents, and caregivers to take a break from interpreting “the big picture” of today’s news coverage about refugees and migrants, coverage that often presents these people and their circumstances in simplistic ways. Instead, we can let the documentary voices of young people onstage speak directly to young people in the audience.

This adult guide is designed to facilitate the start of a conversation.

The Human Journey

The play Cartography is one in a series of programs in The Human Journey, a season-long artistic collaboration among The Kennedy Center, National Geographic Society, and National Gallery of Art. These identified performances and exhibits invite audiences to investigate human experience through the performing arts, science, and visual art.

Cartography features all of the main themes that form the framework for The Human Journey project—namely migration, exploration, identity, and resilience. These four themes are described here:

Migration is the movement of people from one place to another, whether by force or choice, in search of a better living situation. “This movement of people has historically brought together cultures from around the globe, shrinking our planet and bringing the cultural identities that define us into sharper focus,” said Tracy Wolstencroft, chairman and CEO of the National Geographic Society.

Exploration is the human endeavor to discover and better understand the world. The urge to discover can mean turning inward to reveal the mysteries of human biology and psychology, outward to explain secrets of our planet and universe, or toward each other to untangle the jumble of humanity and its relationships and social systems.

Identity relates to how we see ourselves and others, and how we form and apply ideas about who we are. In Cartography, this theme is central as the identities of these young refugees leave their familiar lives and cultures behind.

Resilience describes our ability to endure and function, especially under pressure and stress. Cartography dramatizes the various ways the characters stay strong and hopeful under life-churning circumstances.

With migration and refugees frequently in today’s news, the central ideas of The Human Journey programs are very relevant. Keeping them in mind can help us relate the stories in Cartography to our own lives.

Video: “What Does It Mean to Be a Refugee?” by Benedetta Berti and Evelien Borgman. June 16, 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=25bwiSikRsI

youtube

A Different “Kind” of Theater

Cartography is a type of theater known as “devised documentary theater.” This style of stage performance is developed by a collective where performers collaborate and improvise on specific topics or themes—that’s the devised part. For example, the director may call out a word and have the performers act out their responses. As a group, they see and discover effective scenes and onstage moments and craft them into a script. New York’s Wooster Group and Elevator Repair Service are two well-known theater companies that specialize in devised theater.

“Documentary theater” draws on news stories and interviews with real people. The performance dramatizes a story by portraying events, sometimes using people’s actual words. Documentary theater includes “investigative theater” that is based on investigative/exploratory journalism. The Laramie Project (2000)—which recounts the murder of gay college student Matthew Shepard based on interviews with people in Laramie, Wyoming—is a frequently produced example. “Verbatim theater” is another form of documentary theater, performed using only the words of people interviewed. The works of Anna Deavere Smith are examples, including Fires in the Mirror and Notes from the Field.

Using Open-ended Questions

To set the tone for discussions with young people, consider sharing something from your personal experience that relates to the play and its themes. The intention is to start conversations and keep them going. However, avoid putting any students on the spot about their own identity or family history.

You can use open-ended questions to help students spot details they may have missed, to dive deeper into the play’s content and themes, and engage with potentially controversial content that may come up in discussions such as issues of religion, race, and poverty. When necessary, encourage students to back up their interpretations or views with supporting evidence from the play itself or a trustworthy third-party source.

Here are several open-ended points of discussion to consider:

Have students describe the set of Cartography and how it is used.

As a collaborative exercise, recount notable moments in the performance: What got your attention or surprised you?

How did you feel when the cast left the stage and interacted with audience members?

What new information or ideas came to mind by the end of the performance?

What are examples of major human migrations in history? What factors contributed to them?

Before the Show

Along with your young people, discuss and decide how they want to prepare for attending Cartography. First stop, review the Student Guide with them. Then ask: What do they already know about human migration? What more would they like to learn? Do they want to research their family’s own migration history? Are they interested in the asylum process? Do they want to learn more about documentary theater? Would they like to take an online tour of the Kennedy Center?

Consider following their lead on how they want to prepare, from theater etiquette and stagecraft to background research on human migration to themes in Cartography. Below are some ready resources to draw on.

After the Show

Collaborate with your students or young people to determine how they want to process the play afterward. Let them brainstorm ways to get the most out of the experience and make the subject relevant to them. Do they want to go deeper into the play’s themes? Talk about acting and stagecraft? Learn more about migration and refugees in their community or state?

The Student Guide

Revisit the two sections from the Student Guide: “Check This Out…” and “Think About This….” Use them to stir discussion about the production, scenes in the play, and its characters and themes.

Consider Activities on Three Main Themes in Cartography

Cartography zeroes in on three main themes, or big ideas: Migration, Home, and the Role of Storytelling. Review activities in the “Take Action” section of the Student Guide, such as creative writing, geography, and artistic projects that students can use to explore these ideas in relation to their own lives. These themes overlap with those of the Human Journey series: migration, exploration, identity, and resilience.

The activities in the Take Action section of the Student Guide are designed to be easily scalable for a diversity of learning styles and/or abilities. For example, the acrostic poem exercise can use shorter words and the identity collage activity can be presented with a limited scope, say five pictures and five favorite things.

A Classroom of Pen Pals

Refugees and detained asylum-seekers face a long and often lonely road as they seek to start a new life in a new land. Receiving a letter in the mail can be a highlight of their day, even from someone they may never meet. To find out how your young people can use their writing to connect with other young people who could use a friend, check out: https://www.care.org/get-involved/letters-hope.

Q & A with Christopher Myers

Christopher Myers is an American author and illustrator of children’s books. His illustrations in Harlem won a Caldecott Honor in 1998, and Black Cat earned a Coretta Scott King Award in 2000. He has illustrated and/or written some 20 books and is also a visual artist who designs clothing. Cartography is his first play. He lives in Brooklyn, New York, but travels worldwide. You can visit his website at https://www.kalyban.com.

Kennedy Center: How did the idea for Cartography take shape?

Christopher Myers: In 2016, there was a massive influx of refugees into Europe from Afghanistan, Syria, Somalia, Eritrea, West Africa. I was spending time at the International Youth Library in Munich, Germany, and that area was receiving thousands of refugees every day. I had this thought, that while there was obviously a need for social services, there was also a need for storytellers, too. The act of migration is an act of storytelling, an imagination of a future, a rewriting of the past. Storytelling is central to the process of moving, and it is essential that alongside medical assistance and social assistance that we think about the stories that have drawn our borders and our needs to cross them.

The library provided space and support for myself and my collaborator Kaneza Schaal to talk with and work with these young refugees. They ranged from 11 to 17 years old and came from all across the world.

KC: What role did director Kaneza Schaal play in developing the play?

CM: Kaneza is an ideal collaborator. We were working with young people who spoke Arabic, Pashto, French, and other languages, and communication presented its own challenges. But Kaneza brought the language of theater and performance which is more than just words—it’s movement and action and sound and images. She created a framework to allow these young people from a mix of cultures to express whatever they wanted to say. It was her idea that we could build a community around the conversations we had seen the need for in Munich, take the work we were doing outside the walls of the library, and that her art form, theater, would be an ideal way to do that. Our process is very collaborative. I write scenes and texts and then bring them to her and she asks for more or less, hones the vision of the piece, brings the team of performers together, makes the piece truly breathe as theater, and not just as words on a page.

KC: The importance of stories is a recurring theme in the play. Why is storytelling important, especially for refugees?

CM: These young people urgently wanted to share the stories about their lives, and I think young people in general are desperate for stories—to tell as well as hear them. In a very real sense, they all are in the process of writing their own.

What I found is that, more than most people, these young people must contend with stories being told about them in newspapers and other news coverage. They, themselves, rarely have a chance to tell about their experiences. Journalism is important, but it can have a flattening effect on the human side of the experience of being a refugee or migrant. It has a way of erasing their individuality and humanity. That’s why I say it’s important to have storytellers on the front lines of any crisis, to shape both our human reaction to the crisis, and to shape our understanding of the people who are undergoing such radical change in their own lives.

In the end, we are the sum total of the stories that have come before us and the stories we tell about our futures. That’s true of anyone. We’re also hungry for stories to help us make sense of what’s happening to us and around us. For a young person, it’s about having the opportunity and ability to write the next chapter of their lives, and by developing this show we want to have a part in that. Storytelling is a source of empowerment. If you don’t write your own story, someone will come along and write it for you.

There was a young man from Syria. I asked him what he wanted me to bring back to the world from our time working together. He told me he didn’t want to be invisible anymore. He wanted us to make a place for people in crisis like himself to be seen.

KC: Often, we don’t think of the stories of refugees as having much humor in them, and yet there are laugh-out-loud moments in the show. Were you surprised at all by the jokes and humor shared by the young people you worked with?

CM: I think too often when we create art about people in crisis, we focus on the crisis and not the people. So many people who I’ve met, who are going through a crisis have had a way of finding the humor. Humor is a kind of a way out, an escape or safety valve. Humor is how we fully acknowledge the challenges we face but still give ourselves agency.

These young people we worked with used humor as a tool. They are not simply poster children with tears in their eyes. We want nothing more from this piece than to remind ourselves and our audience of the personalities behind the statistics.

KC: You have mainly written and illustrated children’s books in the past. Why create Cartography as a play?

CM: Theater has all kinds of unique storytelling devices. It combines light and sound, spoken words and action. It can communicate in ways that pictures and the written word can’t. These stories are better told on stage.

Every theater audience is an instant community. It gives us a chance to think about these and other issues as a community and not just as individuals, and that is super important to Kaneza and me.

KC: Stories of human migration run throughout human history. Why is this show particularly timely now?

CM: Everyone has a story of migration in their past. My grandfather came to the United States from Germany in the 1920s. Kaneza’s family fled strife and genocide in Rwanda. We are all on the continuum of migration; we are all part of this story.

Movement is part of what it means to be human. It helps us see our place in the grand scheme of things and in relation to each other. I really want young people to see themselves in that context, whether their stories are personal or farther back in their family’s history.

I was visiting an art museum in Germany with Makhtar, a boy from Mali [in West Africa]. And there was this painting from the 1700s of Mary, Joseph, and the baby Jesus. I explained it was the story of their flight into Egypt. They were fleeing great violence. Makhtar looked at that painting, that story, and said, “They were refugees, too.”

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Data Bank

Here are a handful of graphs to help you and students examine the context and the bigger picture of migration patterns. They present some of the numbers behind the news coverage as well as the play.

A clear definition of what constitutes a refugee was adopted after World War II as part of the United Nations’s 1951 Refugee Convention. According to Article 1(A) of the convention, a refugee is a person:

who owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it.

Today, there are more than 63 million refugees in the world, according to the United Nations High Commissioner on Refugees. That figure surpasses the estimated 60 million Europeans displaced during World War II (1939-1945).

Online source: https://www.vox.com/world/2017/1/30/14432500/refugee-crisis-trump-muslim-ban-maps-charts

Refugees and people seeking asylum 2017, by country of origin

Online source: https://www.refugeecouncil.org.au/getfacts/statistics/intl/global-trends-2017/

Refugees and people seeking asylum 2017, by country of asylum

Online source: https://www.refugeecouncil.org.au/getfacts/statistics/intl/global-trends-2017/

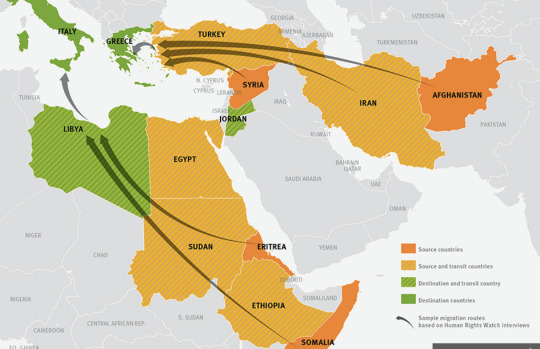

Where Migrants and Refugees Are Coming from and Going, 2015

Source: Human Rights Watch: https://www.hrw.org/report/2015/06/19/mediterranean-migration-crisis/why-people-flee-what-eu-should-do

Video: “UNHCR Global Trends 2017 Report.” UNHCR, The UN Refugee Agency. Overview of the world’s refugee crisis. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1MGRB5ZmKpU&t=41s

youtube

Standards Connections:

English Language Arts - Reading: Literature (RL.7, RL.9)

-

Writer: Sean McCollum

Content Editor: Lisa Resnick

Logistics Coordination: Katherine Huseman

Producer and Program Manager: Tiffany A. Bryant

-

Cartography is part of the Kennedy Center's Human Journey www.kennedy-center.org/humanjourney

The Human Journey is a collaboration between The Kennedy Center, National Geographic Society, and the National Gallery of Art, which invites audiences to investigate the powerful experiences of migration, exploration, identity, and resilience through the lenses of the performing arts, science, and visual art.

David M. Rubenstein

Chairman

Deborah F. Rutter

President

Mario R. Rossero

Senior Vice President

Education

Bank of America is the Presenting Sponsor of Performances for Young Audiences.

Additional support for Cartography is provided by A. James & Alice B. Clark Foundation; the Kimsey Endowment; The Morris and Gwendolyn Cafritz Foundation; Paul M. Angell Family Foundation; and the U.S. Department of Education.

Funding for Access and Accommodation Programs at the Kennedy Center is provided by the U.S. Department of Education.

Major support for educational programs at the Kennedy Center is provided by David M. Rubenstein through the Rubenstein Arts Access Program.

Kennedy Center education and related artistic programming is made possible through the generosity of the National Committee for the Performing Arts.

© 2019 The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts

0 notes