#baby stop melodramatically playing the piano and come back to bed

Text

doomed yuri dungeon lord farcille .... oh how i love u

#delicious in dungeon#dungeon meshi#my art#fanart#this took way too long#farcille#dungeon meshi spoilers#dunmeshi#dunmeshi spoilers#marcille donato#falin touden#baby stop melodramatically playing the piano and come back to bed#dont zoom in

549 notes

·

View notes

Link

Photo: Ron Galella, Ltd./WireImage

The first time Britney Jean Spears ever left America was to go to Stockholm in 1998. It was spring, and in less than a year, the fruits of ten days of labor there would be out in the universe. With it, the hardest-working, most successful teenage superstar of the 1990s would have a debut album. Prior to that, she was just a 15-year-old Mouseketeer — a former classmate of future ex-boyfriend Justin Timberlake, future ex-rival Christina Aguilera, and Ryan Gosling. On her first international voyage away from her small hometown Kentwood, Louisiana, she met a bunch of bearded Swedish producer-songwriter dudes (no disrespect to the now-monolithic Max Martin, and the sadly departed Denniz Pop), and together they made pop history and miscellany.

Perhaps that context is why …Baby One More Time (named, of course, after the Goliath breakthrough single) is the listen it is 20 years later. It wasn’t the reactive album conception we’re accustomed to now. It came before album rollouts were meticulously mood-boarded in the wake of one viral online hit, and plotted with the use of some neurotic, algorithm-assisted A&R development program. Spears’s debut was a bunch of songs she’d recorded before her opening statement changed the course of popular music.

That single — and title track — moved the earth with its first bars. Those first few seconds still sound like an intergalactic alarm clock rousing us from a faraway planet inhabited by horny robots. “DUR! DUR! DUR!” they warned. The Millennium Bug was coming to wipe us out and MTV was the most likely host for the final dance party. The single remains one of the signature pop songs of its ilk, borrowing from the school of Backstreet Boys and ’N Sync but with a new melodramatic, turgid molasses of beats and piano stabs that sounded as heavy as the distress their lovesick narrator suffered.

There is no second “… Baby One More Time” on the record. Her third single “(You Drive Me) Crazy (The Stop Remix)” was the closest contender, but still planets away from that entrance point. To listen to Spears’s debut front-to-back is to travel back to a distant past where the wool was willingly pulled over audience’s eyes and fans were satisfied with being hit over the head by a song without needing to know the who, where, and what from whence it came. This was before we gained a bird’s-eye real-time view of the warts-and-all process of cherry-picking backwoods talent on X Factor. It was before that accessibility worked the other way, and the likes of Lorde could launch a career online from the end of the Earth. Nobody in a pre-social-media era demanded logical intent from their overnight superstars. The aim was to use the vessel that was Spears and build a catalogue of danceable teen bops for her to perform in the malls where she made her first touring appearances. The LP’s clean fun also established a foundation from which she’s since built a career far longer than this album ever anticipated. The foundation is listenable and enjoyable, yet questionable, flawed, bizarre, and epically over the top.

Spears had a voice that was bigger than her life story so far. It was not the voice of an innocent small-town girl. “…Baby One More Time” could be sung by a 15-year-old or a 40-year-old. Spears’s voice was perhaps a problem. The Britney-isms were fine, great even: bay-buh versus bay-bee, and an inflection so nasal that one of her backing vocalists once told the press she pinched her nose while recording her takes for the album to match Spears’s. Those affectations lend her a sort of pop-star weirdness, but it’s the rich depth of her voice that creates an issue: It’s too serious for frivolities, like a ball gown she can’t fit into yet but has to wear anyway. In attempt to match it, her collaborators tried both adult contemporary and tween jingles on her in the hopes something would stick.

Take the reggae-inspired “Soda Pop,” a song riffing on the addictive nature of soda (“open the soda pop, bop-shee-bop-shee-bop”). You may ask again: What planet did this come from? The charming bamboozlement of “Soda Pop” notwithstanding, silliness is not Spears’s legacy. Pain, solitude, gut-wrenching rejection — this is where she lives. Not to shade her performance on “Soda Pop.” There is not another singer in the world who could run lines around the lyric “the pop keep flowin’ like it’s fire and ice,” and ready it for a highly anticipated debut album release. Artists like Billie Eilish are decidedly not recording a “Soda Pop” at the moment.

More confusing than “Soda Pop,” however, is her presentation. The consistent message of Spears’s story arc has been the innocent-until-proven-otherwise mantra. Her album’s material conflicted with her physical presentation. What she did with her body and what she said via her mouth were worlds apart. For example, contrast the album-cover art with her first Rolling Stone cover. The latter was shot by David LaChapelle, and featured Spears on her bed in lingerie, a Tinky Winky doll brushing her nipple. Oh to be a fly-on-the-wall during the decision-making process about which Teletubby was going to work best. Even after two albums, Spears remained on the fence with her third record, Britney, concluding at the age of 20 that she was “not a girl, not yet a woman.” But the seeds of the oversexed virgin enigma were born on …Baby One More Time with its advanced lyrical appeal to the perils of thwarted romance.

The schmaltzy “I Will Still Love You,” a homogenous duet with Don Philip about undying love so burdensome the tryst sounds like life imprisonment. Then there’s single “Born to Make You Happy,” which is emo-level tortured. “I don’t know how to live without your love,” she sings on the piano-driven hit. She was 16, channeling emotions that are on par with Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet (incidentally, nobody was pretending those guys were just holding hands). She plays the doting, subservient girlfriend, always on the other end of the phone, neither a threat to the school jock nor to his mom and dad. And yet she burns with the desire of a thousand Jackie Collins novels.

It made sense that this was Spears’s oeuvre. She would reveal on TV appearances that she was a student of Mariah Carey and Whitney Houston. She was eager to be considered a singer-songwriter. Before the train pulled out from the station, she was looking to position herself as a younger Sheryl Crow. After sexing up the Catholic-school-girl look, she was a lifetime away from Crow, but the songs were rooted in a similar world of romantic balladry; one in which love is as intoxicating as it is near fatal. There are hints at her own inspirations too. Natalie Imbruglia in “I Will Be There” — a guitar-based number, which has a post-chorus wailing guitar line that borrows heavily from “Torn.” Cher is referenced with a great cover of Sonny & Cher’s “The Beat Goes On,” which came before Cher resurrected her career with “Believe” and auto-tune.

The album is also a time capsule for the desperate, but still lucrative, state of MTV in the late ’90s, appeasing the erratic genre-bending of the network’s jukebox before it imploded. It features a ton of, at the time, commonplace production bells and whistles: the sci-fi whirring effects transitioning into verses (“Sometimes”), the copious cowbell (“(You Drive Me) Crazy”), the sprinkles-of-stardust keys (“Deep in My Heart”), the bouncing synths (title track). Stepping into the future was the song, “Email My Heart” — which Rolling Stone called “pure spam.” In an interview from 1999, Spears discusses its inception: “Everyone’s been doing emails, and it’s [called] ‘Email My Heart’, so… everyone can relate to that song!” Turns out Spears would have the last laugh considering the intimacy of our online discourse two decades later.

The critic Jon Caramanica wrote in the New York Times that Spears’s blueprint of pop is but one subsection of the genre now, which makes sense when you listen back. We live in an age where pop is supposedly controlled by us, not them. This album does not sound like supply meeting demand. Nobody would have streamed most of …Baby One More Time if it came out now. It’s a mess. And yet it’s her biggest seller to date. Producing five hit singles, it made her the Antichrist among critics and purveyors of “real” music. In its review of the album, NME wrote: “Hopefully, if she starts to live the wretched life that we all eventually do, her voice will show the scars, she’ll stop looking so fucking smug, she’ll find solace in drugs and we’ll be all the more happier for it.” It was a different time.

0 notes

Text

Nansook Hong – In the Shadow of the Moons book, part 3

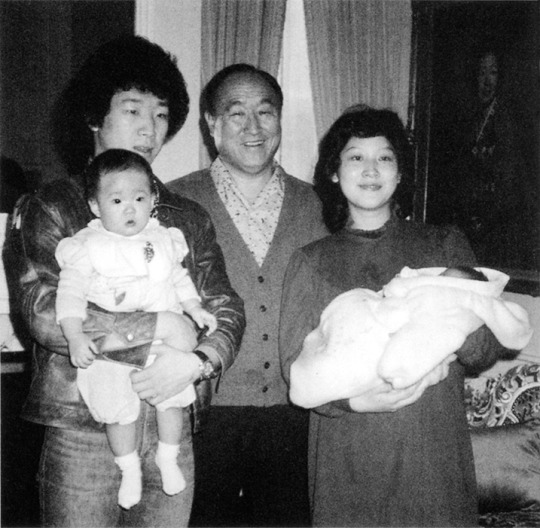

I am holding our first baby, and Hyo Jin is holding the youngest child of Sun Myung Moon.

In The Shadow Of The Moons: My Life In The Reverend Sun Myung Moon’s Family by Nansook Hong 1998

Chapter 4

page 74

I entered the United States illegally on January 3, 1982. In order to obtain a visa, the Unification Church concocted a story about my participation in an international piano competition in New York City.

Had American immigration officials only heard me play, they would have recognized the ruse immediately. A pianist of my limited abilities would not have been among the contestants had such an event actually existed. To lend credence to the claim, the Reverend Sun Myung Moon had the best piano student at Little Angels school accompany me to New York for the same phony recital.

I confess I did not give much thought to the deceit that frigid winter day when my parents and I waved good-bye to my brothers and sisters and left for America. We accepted the Reverend Moon’s view that man’s laws are secondary to God’s plan. By his rationale, a fraudulently obtained visa was no less than an instrument of God’s design for my Holy Marriage to Hyo Jin Moon.

The truth is, I had not been thinking much at all in the six weeks since our engagement. Looking back, what I most resembled was a porcelain windup doll. Turn the key and she walks, she talks, she smiles. I was a schoolgirl, overwhelmed by the transformation I had undergone literally overnight. One day I was a child, shooed from the room whenever adults were discussing serious matters. The next day I was a member of the True Family, fumbling for the appropriate response when my elders bowed before me.

After Hyo Jin and his parents returned to America, my mother and I spent weeks shopping for a wardrobe that would match my metamorphosis from girl to woman. Gone were my school uniforms, my T-shirts and blue jeans. My teenage self was buried beneath tailored business suits and conservative sheaths. Awkward though I felt in this new role, I savored the attention. What girl would not revel in a round of dinner parties thrown in her honor? Whose head would not be turned by the solicitations of those so many years her senior?

If there was any hint of the troubles to come, it was in the discomfort I felt in the company of my intended. In December Hyo Jin Moon returned briefly to Korea, without his parents. Our meetings were strained as much by our lack of common interests as by his relentless pressure for sex. My mother had given me several books to read about marriage, but I was still unclear what the sex act actually entailed.

Hyo Jin took me to the Moon family’s home in Seoul during his visit and, under the pretext of showing me his room, cornered me by his bed. “Lie down with me,” he said. “You can trust me. We’ll be married soon.” I did as he asked, only to stiffen with fear as his clearly experienced hands groped my body and his fingers fumbled with layer upon layer of my winter clothing. “Touch me here,” he instructed, his hands guiding my own along his inner thigh. “Stroke me there.”

Sex before marriage is strictly prohibited by the Unification Church. Because Sun Myung Moon teaches that the Fall was a sexual act, incidents of premarital or extramarital sex are considered the most serious sin one can commit. Here I was, a scared and virginal girl of fifteen, having to remind the scion of the Unification Church, the son of the Messiah, that we both risked eternal damnation if I did as he demanded. He seemed more amused than angry at my righteous naivete. For my part, I believed with all my heart that God had chosen me to guide Hyo Jin away from his sinful path.

I had no idea how difficult that task would be. Even as the Korean Airlines jet landed at Kennedy International Airport in New York, I gave no thought to what my life actually would be like in America, a world away from everything I knew and everyone I loved. Humbled by my selection as Hyo Jin Moon’s bride, swept up in events being orchestrated by others, I did not ask myself how a mere mortal would fit into the “divine” family of Sun Myung Moon or how a virtuous girl could tame an older rebellious youth like Hyo Jin Moon.

As we deplaned in New York, I became separated from my parents in the crush of travelers being herded into lines for U.S. customs. The uniformed agent looked annoyed when I handed him my two large suitcases. He spoke brusquely to me, but because I did not speak English, I could not answer his questions. There was a flurry of activity and some shouting before someone came to assist me.

I watched as the customs agent dumped my neatly folded clothes onto the counter, searching the side and back pockets of my luggage. What was he looking for? What would I have?

It did not occur to me that the customs agent had reason to be suspicious. Where was my sheet music for this piano competition? Why had I packed so much for such a brief trip? Wasn’t I wearing thousands of dollars’ worth of necklaces given to me as engagement gifts in Korea? Hadn’t church leaders told me to hide them beneath my sedate brown dress?

I was arriving in the United States at the height of American antipathy toward Sun Myung Moon. He was reviled in the United States as a public menace on the order of the Reverend Jim Jones, the leader of the Peoples’ Temple cult who, in 1978, had fed more than nine hundred of his followers cyanide-laced fruit juice in a mass suicide in Guyana. The newspapers in America were full of stories about young people being brainwashed into following Sun Myung Moon. A cottage industry of “deprogrammers” had sprung up across the country, paid by parents to kidnap their children from Unification Church centers and “reeducate” them.

Having been born into the Unification Church, I knew little firsthand about the recruitment techniques that had made the church so controversial. I was skeptical about such melodramatic descriptions as “brainwashing,” but it was certainly true that new members were isolated from old friends and family. Church members were encouraged to learn as much as possible about new recruits in order to tailor an individual approach to win him or her over to the Unification Church. Members would “love bomb” new recruits with so much personal attention it is hardly any wonder that vulnerable young people responded so enthusiastically to their new “family.”

It was a recruit’s old family that usually suspected sinister motives in this all-embracing religious community. The year I came to America, it was not uncommon for travelers to be approached at airports, at traffic signals, or on street corners by young people selling trinkets or flowers for the Unification Church. Begging is hard and humiliating work and followers of Sun Myung Moon did it better than most. Asking for money is easier when you believe your panhandling is going to support the work of the Messiah.

The American government had as many questions about Sun Myung Moon’s finances as American parents had about his theology. Senator Robert Dole, the ranking Republican on the Senate Finance Committee, had concluded hearings on the Unification Church with a recommendation that the Internal Revenue Service investigate the tax status of the Reverend Moon and his church. Only a month before my engagement, a federal grand jury in New York had indicted the Reverend Moon, charging him with evading income taxes for 1972 to 1974, as well as conspiracy to avoid taxes. No doubt that indictment had more to do with the scrutiny I received at JFK International Airport than the size of my suitcases did.

I knew none of that then, of course. I knew only that I was coming to America to join the True Family. Hyo Jin Moon paced impatiently outside the customs area. As I emerged, shaken from my ordeal, I looked around for the reassurance of my parents, but Hyo Jin hustled me to the parking area and his black sports car, an engagement gift from his father. He carried a small bouquet of flowers but was so exasperated by the delay he almost forgot to give them to me. My parents would meet us at East Garden, he said. I was too tired to object.

It was a silent, forty-minute drive north from New York City to Westchester County, through the wealthy suburbs where Manhattan’s corporate executives and professional elite make their homes in quaint, rural towns along the Hudson River. It was late. It was too dark to see much and I was too tired to care.

I paid more attention as we drove through the black, wrought iron gates. This was East Garden, at last. Hyo Jin acknowledged the guard at the security booth and headed up the long, winding driveway. Even in the dark, I thought I could make out the exact spot on the rolling lawn that I had gazed at reverentially for so many years. In our home in Korea, my family displayed a photograph of the True Family, seated on the emerald green grass of their American estate. I used to stare at that photograph, unshakable in my belief in the perfection of the individuals pictured there. In their expensive clothes, posed in front of their magnificent mansion, they represented the ideal family we prayed to emulate. I treasured that photograph the way other teenagers treasured photographs of rock ’n’ roll stars.

The Reverend and Mrs. Moon and the three oldest of their twelve children greeted us at the door. I bowed down to Father and Mother, humbled to be in their home. I listened for the sound of another car as I was led through the enormous foyer into what they called the yellow room, a beautiful solarium. Where were my parents? When would they and the church elders come? Surely I would not have to converse alone with the Reverend and Mrs. Moon!

As I entered the house, I stopped to take off my heavy winter boots. In Korea one never enters a home without first removing one’s shoes. It is a sign of respect as well as an act of fastidiousness. Hyo Jin’s sister, In Jin, stopped me. I should not keep her parents waiting. In the yellow room, we exchanged pleasantries about my trip. I smiled and said little, keeping my eyes downcast. It is impossible to overstate the level of my nervousness. I had never been alone in the company of the True Family. I was nearly paralyzed by a mixture of fear and reverence. I was relieved to hear the slam of a car door signaling the arrival of my parents.

While our parents conversed downstairs, Hyo Jin took me on a brief tour of the mansion. As large as it was, the house seemed to be bursting with children and their nannies. When I arrived in America, Mrs. Moon was pregnant with her thirteenth child. Most of the little ones and their baby-sitters were asleep that night in their barracks-like quarters on the third floor. Seeing them tucked in their beds made me ache for my own younger brothers and sisters back home in Korea, especially the youngest, Jin Chool, who was six years old.

It was well past midnight when we said good night to the Moons and a driver took my parents and me to Belvedere, the church-owned estate a few minutes from East Garden where guests often stayed. First my parents were shown to a room, then I was escorted down the hall to the most beautiful bedroom I had ever seen. Decorated in shades of pink and cream, the room was fit for a princess. In addition to the queen-sized bed, the room had a living area with a large couch and comfortable armchairs. It had a crystal chandelier and two walk-in closets bigger than some of the rooms we rented in Seoul when I was small. The bathroom was enormous, its original blue-and-white hand-painted tiles retaining the elegance of the 1920s, when the mansion was built.

I had never seen such a room. There was even a television set. I fumbled with the controls, and though I did not understand a single English word, I quickly discerned that I was seeing some kind of advertisement. I wish I had a photograph of my expression when I realized that I was watching a commercial for dog food. Special food for dogs? I was transfixed by the scene of a dog scampering across a kitchen floor to a bowl full of brown nuggets. In Korea, dogs eat table scraps. I fell asleep on my first night in America in a state of wonder — I was living in a country so rich that dogs had their own cuisine!

In the morning a driver returned to take my parents and me to the Moons’ breakfast table in the wood-paneled dining room at East Garden. This is where the Reverend Moon conducts his business and church affairs. Every morning leaders come here to report to him in Korean about his financial enterprises around the globe. At the long rectangular dining table, the Reverend Moon decides what projects to fund, what companies to buy, what personnel to promote or demote.

The Moon children do not eat their meals with their parents. They appear at the breakfast table to bow to the Reverend and Mrs. Moon each morning to begin their day. Then they are led away to the kitchen, where they are fed before school or playtime. On this morning, the older children joined their parents and mine for breakfast. I caught sight of the little ones peeking through the kitchen door to steal a glimpse of me, their new sister. I felt warmed by their giggles but shocked to learn that the younger Moon children did not speak Korean.

The Reverend Moon teaches that Korean is the universal language of the Kingdom of Heaven. He has written that “English is spoken only in the colonies of the Kingdom of Heaven! When the Unification Church movement becomes more advanced, the international and official language of the Unification Church shall be Korean; the official conferences will be conducted in Korean, similar to the Catholic conferences, which are conducted in Latin.” I knew that members around the world were encouraged to learn Korean, so I was confused by the failure of the Reverend and Mrs. Moon to teach their own children what I had been taught was the language of God.

I was overpowered that morning by the strange smells of an American breakfast. There was bacon and sausage, eggs and pancakes. The sight of all that food made me slightly nauseous. In Korea I was accustomed to a simple morning meal of kimchi and rice. Mrs. Moon had instructed the kitchen sisters to serve papaya, her favorite fruit. She knew I would never have tasted such an exotic delicacy and she kept urging me to try some. She showed me how to sprinkle the fruit with lemon juice to enhance the flavor, but I simply could not eat. She looked displeased. My mother ate the papaya placed before me and praised Mrs. Moon for her excellent choice.

The Reverend Moon sensed my unease. He spoke directly to Hyo Jin: “Nansook is in a strange place, in a foreign country. She does not speak the language or know the customs. This is your home. You must be kind to her.” I was so grateful to have my fears acknowledged by the Reverend Moon that I only vaguely noticed that Hyo Jin said nothing in response.

Hyo Jin did come to see me at Belvedere but his few visits were not reassuring. They only reinforced how ill-suited we were to one another. I was afraid of him. He would try to embrace me and I would pull away. I did not know how to be with a boy, let alone with a man I was soon to marry. “Why are you running away from me?” he would ask. How could I tell him what I was too young to understand myself? I was honored to be the spiritual partner of the son of the Messiah but I was not ready to be the wife of a flesh-and-blood man.

I passed through the next four days as if in a series of dream sequences. I moved from scene to scene, numb from exhaustion and the magnitude of unfolding events. I went where I was directed. I did as I was told, concerned only that I make no mistakes that would displease the Reverend and Mrs. Moon.

Mrs. Moon took my mother and me shopping at a suburban mall. I had never seen so many stores. Mrs. Moon gravitated to the most expensive shops. At Neiman-Marcus she selected unflattering, matronly dresses in dark colors for me to try on. She chose bright red or royal blue outfits for herself. I suspect that she resented my youth. She had heard her husband on my engagement day say that I was prettier than she. It was hard for me to imagine a woman as stunning as Hak Ja Han Moon being jealous of anyone, especially a schoolgirl like me. She had been only a year older than I when she married Sun Myung Moon. At thirty-eight, pregnant with her thirteenth child, she still had the flawless skin and facial features of a great beauty.

She was outwardly generous to me, summoning me to her room that first week to give me a dress she no longer wore and a lovely gold chain. I took the chain off in her bathroom as I tried on the dress and mistakenly left it on the sink. She sent her maid to me later at Belvedere to give me the necklace. Mrs. Moon opened her closet and her purse to me, but from the very first, I felt she closed her heart.

The position of first daughter-in-law in a Korean family is, by tradition, an exalted one. She will inherit the role of mother and be the anchor of the family. There is even a special term for first daughter-in-law in Korean: mat mea nue ri. It was clear from the beginning that I would not fill this role in the Moon family. I was too young. “I had to raise Mother and now I have to raise my daughter-in-law, too,” the Reverend Moon always said. It was only later that I recognized that no outsider would have been allowed a key role in the Moon family. As an in-law, one had to know one’s place. For me that meant when the family was gathered, being the last person to sit in the seat farthest away from Sun Myung Moon.

Given the attention of customs officials that I had attracted at the airport, the Reverend Moon decided it would be prudent to stage a piano recital after all. I was in a panic. I had not practiced. I had brought no music with me. My mother assured me that I could get by with a Schumann piece I had memorized for class at Little Angels. I thought perhaps I remembered it well enough. Hyo Jin and Peter Kim, the Reverend Moon’s personal assistant, drove me into New York City one afternoon to give me a chance to practice on the stage of Manhattan Center, the performing arts facility and recording studio owned by the church in midtown, where the recital would be held.83

I sat alone in the backseat of one of the Reverend Moon’s black Mercedes, staring out at the city as its skyscrapers came into view. I knew I should be impressed, but it was a cold, gray January day. My only impression was how lifeless New York City seemed. In retrospect, that dead feeling may have had more to do with my own emotions; they were as frozen as the concrete landscape outside my window.

At Manhattan Center, we met Hoon Sook Pak, the daughter of Bo Hi Pak, one of the highest-ranking officials in the church. She was Hyo Jin’s age; he had lived with her family in Washington, D.C., during his tumultuous middle-school years. She would later become a ballerina with the Universal Ballet Company, Korea’s first ballet troupe, founded by Sun Myung Moon. They greeted one another warmly in English, though both spoke fluent Korean. I stood there mute while they chatted at great length. I could feel my cheeks burn. Why were they ignoring me? Why were they being so rude? I got even angrier when Hyo Jin left me in a small anteroom while he went to talk to some other people. “Stay here,” he instructed as if I were a puppy he was training to obey.

I felt a surge of that familiar stubborn pride that had provoked so many childhood arguments with my brother Jin. As soon as Hyo Jin was out of sight, I went exploring. The performing arts center is adjacent to the old New Yorker Hotel, now owned by Sun Myung Moon. The church uses the hotel to house members. The entire thirtieth floor is set aside for the True Family, to accommodate them on their overnight stays in New York City. I wandered around, jiggling the doorknobs of locked rooms.

Hyo Jin was furious when he returned to find that his pet had not stayed put, as ordered. “You can’t just go off like that. You are in New York City. It’s dangerous,” he screamed. “Someone could have kidnapped you.” I said nothing but I thought, “Pooh! Who would kidnap me?” Mostly I hated that this rude boy thought he could tell me what to do.

Hundreds of church members filled the concert hall on the night of my performance. I was a small part of the evening’s entertainment. I was the third of several pianists to play. I wore a long pink gown that my mother had bought for me before we left Korea. My stomach was doing somersaults, whether from the sushi I’d eaten at lunch or from the prospect of performing for the True Family, who were seated in the theater’s VIP box. In Jin, Hyo Jin’s sister, spooned out Pepto-Bismol for me to drink. It worked. I thought of that pink liquid as I did dog food: one of the wonders of America.

I played too quickly. The audience did not know I was done, so there was a delay in the applause. I was just relieved that I had made it through the piece and only missed a few notes. As soon as I got backstage, Hyo Jin and In Jin told me to change into my street clothes. I did as they said, not realizing there would be a curtain call for all the performers at the end of the evening. I could not go onstage dressed so casually, so I took no bows with the others.

In the Moons’ suite in the New Yorker after the show, the Reverend Moon was so pleased with the evening that he decided that a real piano competition should be an annual event. Mrs. Moon, however, was icy toward me. “Why didn’t you take your bow with the others?” she snapped. “Why did you change your clothes?” I was taken aback. What could I say? That I had done as her son instructed? Hyo Jin watched me squirm and said nothing. I just bowed my head and accepted my scolding.

My failure to appear for the curtain call was not my first infraction, it turned out. Mrs. Moon had been keeping track of my missteps. She enumerated them all for my mother the next day. I had been rude to enter their home wearing my boots; I had been careless to leave the necklace on the sink; I had been ungracious not to eat heartily at mealtime; I had been thoughtless not to take a bow at curtain call. In addition, she told my mother, Hyo Jin complained that my breath was stale. Mrs. Moon sent my mother to me with words of caution and a bottle of Listermint mouthwash.

I was devastated. If first impressions were the most lasting, my relationship with Mrs. Moon was doomed my first week in America.

The wedding was set for Saturday, January 7, in order to accommodate the school schedules of the Moon children. There was no marriage license. We had had no blood tests. I was a year below the legal age to marry in New York State. My Holy Wedding to Hyo Jin Moon was not legally binding. Not that I knew that, or cared. The Reverend Sun Myung Moon’s authority was the only power that mattered.

We attended breakfast with the Reverend and Mrs. Moon in the morning. My mother urged me to eat. It would be a long day. There would be two ceremonies. A Western ritual would be held in the library of Belvedere. I would wear a long white dress and veil. Afterward there would be a traditional Korean wedding, for which Hyo Jin and I would wear the traditional wedding clothes of our native country. A banquet would follow in New York City.

My mother asked Mrs. Moon if I might have a hairdresser arrange my hair and apply my makeup. A waste of money, Mrs. Moon said; In Jin would help. I worshiped In Jin as a member of the True Family, but I was not so certain I trusted her to be my friend. She did as her parents asked, winning their praise for her kindness to me, but I could see that I was no more her type than I was Hyo Jin’s. As she dusted my face with powder, she offered me some advice. I would have to change, and fast, if I was going to fit in with the Moon children, especially my husband. “I know Hyo Jin better than anyone,” she told me. “He does not like quiet girls. He likes to have fun, to party. You need to be more outgoing if you want to make him happy.”

Hyo Jin looked pleased enough when he stopped by to see me just before the ceremony, but I knew I was not the source of his happiness. On this day he would be his father’s favorite, the good son, not the black sheep. He even agreed to trim his long shaggy hair to please his parents.

As I walked alone down the long hallway that led to the library and my future, an old Korean woman whispered to me, “Don’t smile or your first child will be a girl.” That was an easy instruction to follow, and not just because I knew the great disappointment that greeted the birth of females in my culture. My wedding day was supposed to be the happiest day of my life, but all I felt was numb. I want to weep for the girl I was when I look at the photographs in my wedding album. I look even more miserable in those pictures than I remember feeling.

There was a crush of people on both sides of me as I entered the library and made my way across the room to the Reverend and Mrs. Moon in their long white ceremonial robes. The library was very hot, packed with people, all of whom were strangers to me except for my parents. It was an impressive room, its dark wood-paneled walls lined with old, unread books, its high ceilings hung with chandeliers. It was hard not to believe in that setting that I was fulfilling God’s plan for me and for the future of the True Family charged by him with establishing Heaven on earth. I was an instrument of his larger purpose. The marriage of Hyo Jin Moon and Nansook Hong was no silly, human love match. God and Sun Myung Moon, by uniting us, had ordained it.

It was a smaller group of family and church leaders who attended the Korean rites upstairs in Belvedere. I was learning that the Moons do the most momentous things in life in a hurry, so I barely had time to arrange my hair in the traditional style before I was summoned. I forgot to dot my cheeks in red in the customary manner, a failure noted by Mrs. Moon and the ladies who surround her. Hyo Jin and I stood before True Parents at an offering table laden with food and Korean wine. Fruits and vegetables were strewn beneath my skirt as part of a folk tradition meant to symbolize the bride’s desire to produce many children.

I remember little of the actual ceremony. I was so tired that I relied on the flash of the official church photographer’s camera to keep me focused. I was grateful for orders to “stand here” or to “say this.” If I kept moving, I would not collapse.

A driver took Hyo Jin and me back to East Garden to change our clothes for the reception that would be held in the ballroom of Manhattan Center. He delivered us to a small stone house up the hill from the mansion. With its white porch and charming stone facade, it looked like something out of a fairy tale. This is where Hyo Jin and I would live. We called the place Cottage House. There was a living room, a guest room, and a small kitchen on the first floor. Upstairs was a small bathroom and two bedrooms. Our suitcases, I saw, had been delivered to the larger of the bedrooms.

Hyo Jin insisted that we have sex. I begged him to wait until the night — True Parents expected us to be ready to leave within the hour — but he would not be put off. I did not want to be naked in front of him. I slipped into bed to remove my clothes, a practice I would continue for the next fourteen years. I had read the books my mother gave me, but I was totally unprepared for the shock of sexual intercourse. When Hyo Jin got on top of me I did not know what to expect. He was very rough, excited at the prospect of deflowering a virgin. He told me what to do, where to touch. I just followed his directions. When he entered me, it was all I could do not to cry out from the pain. It did not take very long for him to finish, but for hours afterward, my insides burned with pain. “So this is what sex is,” I kept thinking.

I began to cry, from pain, from exhaustion, from shame. I felt we were wrong not to wait. Hyo Jin kept trying to shush me. Didn’t I enjoy it? he wanted to know. It was very “ouchy,” I told him, using a little girl’s word for a woman’s pain. He said he’d never heard that reaction before, confirming all the rumors I had heard in Korea. Hyo Jin had had many lovers. I was shocked and hurt that he would confess his sin in such a callous and cavalier way. I wept even harder, until his sharp tone and angry rebuke forced me to dry my tears. At least I now knew what sex was and who my husband was. It was horrible; he was no better.

While we were dressing, a kitchen sister called to say that True Parents were waiting for us in the car. We rushed downstairs and into the front seat of a black limousine. Mrs. Moon looked at me accusingly. “What delayed you?” she snapped. “There are people waiting.” Hyo Jin said nothing, but our flushed faces and hastily arranged clothing made our actions evident. I was glad the Moons were in the backseat so that they could not see my shame.

I fell asleep on the drive into Manhattan but my rest was short-lived. The ballroom of Manhattan Center was filled with banquet tables and hundreds of people, most of them American members. They cheered as we entered and took our seats at the head table. I was tired of all the hoopla, but there still were hours of entertainment and dining ahead of me. It was an American meal of steak and baked potatoes and ice cream and cake. My mother urged me to eat, but everything tasted like sand. Despite the Korean flavor of the entertainment, the entire evening was conducted in English. I understood not a word of the many speeches and toasts raised in honor of Hyo Jin and me. I smiled when the others smiled and applauded when the others did likewise.

The language barrier had the effect of making me a spectator at my own wedding. I was in this group but not part of it. I looked around at all the Moons singing, clapping. Everyone looked so happy. It was pretty exciting to watch. I was yanked out of my isolation when my father, who also did not understand English, told me he suspected I would be asked to make some brief remarks. “In English?” I asked, terrified. “No, no,” my father reassured me. “Hyo Jin will translate for you.” My father told me to keep it short, to thank God and the Reverend Moon and to promise to be a good wife to Hyo Jin. When the time came I did as my father said. The room erupted in shouts of “What did she say?” from the non-Korean audience. “Oh, it was nothing important,” Hyo Jin told them as he went on to make his own remarks in English to tumultuous applause.

I kept my hands in my lap as I clapped. The Reverend Moon instructed me to lift them onto the table and told me to applaud more openly to demonstrate my joy on my wedding day and my appreciation of Hyo Jin. I did as he instructed, thinking all the while: “I am such an idiot. Can’t I do anything right?”

The festivities did not end even after we returned to East Garden. It is a Korean tradition for wedding guests to strike the soles of the groom’s feet with a stick for his symbolic thievery of his bride. Back at Cottage House, Hyo Jin put on several pairs of socks in preparation for this ritual assault. The Reverend and Mrs. Moon laughed as church leaders tied Hyo Jin’s ankles together so he could not escape. Every time they hit Hyo Jin’s feet Father would express mock outrage: “Stop, I will pay you not to hit my son.” Those wielding the stick would take his money and resume their beating. “I’ll give you more money if you stop,” the Reverend Moon would shout and again the laughter would begin as they stuffed Father’s money into their pockets and began hitting Hyo Jin again.

I watched the proceedings from a soft armchair that threatened to swallow me straight into sleep. Everyone commented on my calm demeanor. “She does not cry out to them to stop hitting her husband.” I was not calm; I was numb. At the urging of the crowd, I tried to untie his ankles but I was so tired Hyo Jin had to do it himself.

The next morning we all gathered at the Reverend Moon’s breakfast table. Hyo Jin disappeared early, I don’t know to where. I stayed to wait on the Reverend and Mrs. Moon. I was not certain what my role should be in the True Family, and my new husband was little help in guiding me. I fell naturally into the role of handmaiden to Mrs. Moon.

It was not until after the wedding that anyone suggested to me that Hyo Jin and I might take a honeymoon. He wanted to go to Hawaii, but the Reverend Moon suggested Florida instead. Ours was not a conventional wedding trip. We made an odd threesome: husband, wife, and personal assistant to Sun Myung Moon. The Reverend Moon had handed his assistant, Peter Kim, five thousand dollars, with instructions to drive us to Florida. No one told me where we would be going or what we would be doing. My mother, accustomed to the formality of East Garden, packed a suitcase full of prim dresses for me, and I tossed in a single pair of blue jeans and a T-shirt.

Peter Kim and Hyo Jin sat in the front seat of the blue Mercedes. I sat alone in the back. They spoke in English for the eleven-hundred-mile trip down the East Coast. My sense of isolation was complete. The two men decided where and when we would stop to eat or sleep. I remember fighting off tears at a gas station rest room. I could not figure out how the hand dryer worked. I thought I had broken it when it would not stop blowing hot air. It was a small moment, but a lonely one. Such a simple thing and I had no one to ask for help.

I brightened a little when we arrived in Florida and Peter Kim suggested taking me to Disney World. I was a fifteen-year-old girl. I could not imagine a more wonderful vacation spot. Hyo Jin was unenthusiastic. He had been there many times before. He reluctantly agreed to stop in Orlando. It was cold. A light drizzle was falling, but I did not care. I walked down Main Street USA toward Cinderella’s castle and understood exactly why they call Disney World the Magic Kingdom. I kept my eyes peeled for Mickey Mouse or any of the familiar costumed characters, but I would not have an opportunity to see any of them. Ten minutes after we arrived, Hyo Jin declared that he was bored and wanted to leave. I was astounded by his selfishness, but I followed a few steps behind as he led the way back to the Mercedes.

The Reverend Moon had suggested we drive to give me a chance to see some of the United States, but Hyo Jin soon ran out of patience with that plan as well. He summoned a security guard from East Garden to fly down to Florida to pick up the car. We were flying to Las Vegas, he told me.

I had no idea where or what Las Vegas was and neither Hyo Jin nor Peter Kim bothered to enlighten me. Neither did they tell me that the Reverend and Mrs. Moon and my own mother and father were vacationing there. I did not know we would be joining our parents until we walked across the hotel restaurant to the table where they were seated. My mother chastised me for gazing distractedly around the room as I walked toward them. It would only have been disrespectful, I told her, if I had known that the Moons were there and I did not!

I was all the more confused when I learned that Las Vegas is a gamblers’ paradise. There were slot machines in the restaurants, casinos in the hotels. What were we all doing in a place like this? Gambling is strictly prohibited by the Unification Church. Betting of any kind is seen as a social ill that undermines the family and contributes to the moral decline of civilization. Why, then, was Hak Ja Han Moon, the Mother of the True Family, cradling a cup of coins and feverishly inserting them one after another into a slot machine? Why was Sun Myung Moon, the Lord of the Second Advent, the divine successor to the man who threw the money changers out of the temple, spending hours at the blackjack table?

I dared not ask, but I did not need to. The Reverend Moon was eager to explain our presence in a place I had been taught was a den of sin. As the Lord of the Second Advent, he said, it was his duty to mingle with sinners in order to save them. He had to understand their sin in order to dissuade them from it. I should notice, he said, that he did not sit and bet at the blackjack table himself. Peter Kim sat there for him and placed the bets as the Reverend Moon instructed from his position behind Peter Kim’s shoulder. “So you see, I am not actually gambling, myself,” he told me.

Even at age fifteen, even from the mouth of the Messiah, I recognized a rationalization when I heard one.

Chapter 5

page 94

I returned to East Garden a married woman in the eyes of the Unification Church, but to all appearances, I was still a child in need of schooling. If I had harbored any doubts about my second-class status in the family of Sun Myung Moon, the discussions about my education certainly clarified my standing.

With the exception of my new husband, who at nineteen still had not completed high school, the school-age children of the Reverend Moon attended a private academy in Tarrytown. Mrs. Moon made it clear that she had no intention of paying the forty-five-hundred-dollar-a-year tuition at the Hackley School for me. Public school would do.

Early in February, Peter Kim drove me to Irvington High School to enroll me in the tenth grade. We stopped at a convenience store first to buy a notebook and some pencils. I would use the name Nansook Hong. No one was to know of my marriage or of my relationship with the Moon family. Peter Kim presented himself to the principal as my guardian. My report cards would be sent to him. I had been in the top 10 percent of my class at Little Angels Art School back in Seoul, but the prospect of attending an American school filled me with dread. I walked behind Peter Kim through the noisy corridors of this typical suburban high school, taking in the laughter and casual dress of the teenagers rushing past me. How would I ever fit into this scene of pep rallies and junior proms? How would I even understand my English-speaking teachers? How would I ever reconcile being a serious student at school and a subservient wife at home? How would I be anything but lonely living this double life?

I woke every day by 6:00 a.m. in order to greet the Reverend and Mrs. Moon at their breakfast table. The mornings were crazy in the mansion kitchen. No one was ever certain what time the Reverend and Mrs. Moon would come downstairs, but when they did, they expected to be served immediately. The two cooks and three assistants would have prepared a main course, but as often as not, they would have to scurry if the Moons preferred something else. I would already have had a bite to eat in the kitchen before the Moons arrived at the table with a host of church leaders. I would drop to my knees for a full bow when they appeared and wait to be dismissed to the care of the driver who delivered me to school.

I was usually very tired in the morning because Hyo Jin never came home before midnight and demanded sex when he did. More often than not, he was drunk when he stumbled up the stairs of Cottage House, reeking of tequila and stale cigarettes. I would pretend to be asleep, hoping he would leave me alone, but he rarely did. I was there to serve his needs; my own did not matter.

I tiptoed around our room in the mornings, though there was little danger of waking my husband. He slept soundly well into the day; sometimes he was still sleeping when I returned from school. He would rouse himself, shower, and then return to Manhattan to make the rounds of his favorite nightclubs, lounges, and Korean bars. At nineteen, Hyo Jin had no trouble being served in the Korean-owned establishments he frequented. He often took his younger brother Heung Jin, then fifteen, and his sister In Jin, sixteen, with him on his late-night drinking jaunts.

Hyo Jin invited me to join them only once. We drove to a smoky Korean nightclub bar. It was obvious that the Moon children were regular customers; all the hostesses greeted them affectionately. A waitress brought Hyo Jin a bottle of Gold Tequila and a box of Marlboro Lights. In Jin and Heung Jin drank right along with him, while I sipped a glass of Coca-Cola.

I tried to hold them back, but the tears came in spite of my best efforts. What were we doing in a place like this? All of my childhood I had been taught that members of the Unification Church do not go to bars, that followers of Sun Myung Moon do not drink alcohol or use tobacco. How could I be sitting in this place with the True Children of the Reverend Moon while they engaged in the very behavior that Father traveled the globe denouncing?

In the world of funhouse mirrors I had entered, their behavior was not the problem. Mine was. “Why are you being like this?” Hyo Jin demanded before moving in disgust to another table. “You are spoiling everyone’s good time. We came out to enjoy ourselves, not to be your baby-sitter.” In Jin slipped into the chair beside me. “Stop crying or Hyo Jin will get very angry,” she warned me sternly. “If you act like this, he won’t like you.” I had no time to compose myself before my husband yelled, “Let’s go. We’re taking her home.”

No one spoke to me during the long drive to East Garden. I could feel their disdain pressing against me in the overheated car. “Don’t cry,” I kept telling myself. “You’ll be home soon.” Just before Hyo Jin dropped me off, he picked up one of my classmates, a Blessed Child who shared the Moon siblings’ passion for fun. She squeezed into the backseat, not even acknowledging my presence. They practically left skid marks on the driveway in their rush to return to New York.

That was the first of so many nights I cried myself to sleep. On my knees for hours beside our bed, I begged God to help me. “If you sent me here to do your will,” I prayed, “please guide me.” I believed in every chamber of my young heart that if I failed God in this life, I would be denied a place in Heaven with him in the next. What good is a happy earthly life if you don’t go to God?

My knees were raw with carpet burns early the next morning when Mother summoned me to her room. Hyo Jin and the others still were not home. Where were they, she wanted to know. Why wasn’t I with them? Prostrate before her on the floor, I wept as I recounted the events of the previous evening. It was a relief to share this awful burden with Mother. Maybe now something would change. Mrs. Moon was very angry, but not at Hyo Jin, as I had expected. She was furious with me. I was a stupid girl. Why did I think I had been brought to America? It was my mission to change Hyo Jin. I was failing God and Sun Myung Moon. It was up to me to make Hyo Jin want to stay home.

How could I tell her that when her son did stay home, things were no better? He had usurped the living room in Cottage House for the use of his rock ’n’ roll group, the U Band. I hated their all-night practice sessions. The whole house shook when they played or listened to music on his stereo. Hyo Jin insisted that my training in classical music had made me a snob, but my distaste for his band had less to do with the music they played than with the way they behaved in our home. Band members would begin to assemble in the early evening, joined often by other Blessed Children who lived nearby. No sooner would I hear the guitars tuning up than the smell of marijuana smoke would drift upstairs, where I would be doing my homework.

My shock was a source of amusement to Hyo Jin and his friends, I knew, but the truth is my feelings about them were conflicted. I did not want to engage in proscribed behavior, but I was so very lonely upstairs with my schoolbooks. I did not want to join them, but I longed to be asked. I found myself living in an upside-down world, mocked by my peers for believing what we all had been taught, and chastised by my elders for failures that were not my own.

How could I tell Mrs. Moon that her children’s barhopping was the least of their sins? I said nothing while she berated me. It was not long afterward that Mrs. Moon called my mother to her room to catalog my failings. In Jin had reported that I had worn my wedding ring to school. In Jin said I was asking around about Hyo Jin’s old girlfriends.

I had done no such things, but it was impossible to defend myself before the Reverend and Mrs. Moon without seeming to criticize their own children, and that would not be tolerated. I tried to explain this to my own mother, but her only counsel was that I must be more careful not to offend the True Family. I must be cautious when I spoke. I must pray to become more worthy. That didn’t seem possible. I was criticized at every turn, judged guilty without a fair hearing. Too often falsely accused, I became wary of trusting anyone.

How I wished that my father or my brother Jin would come from Korea! The Moons had sent my father back to Seoul soon after the wedding. Jin was still there, too, waiting to finish high school and obtain a visa to join his wife, Je Jin Moon, in the United States. When he came, I knew Jin would be preoccupied with his own life. He talked of attending college at Harvard, and the Reverend Moon seemed willing to send him, my brother’s academic success a feather in the Messiah’s cap. I was thrilled for Jin but sad for myself; I would have to remain in East Garden, surrounded by those who hated me.

Un Jin Moon was an exception. She was a year younger than I. She did not get along very well with In Jin either. We became friendly soon after my arrival at East Garden. I will always be grateful for Un Jin’s kindness in those initial months. Everything was so new and I was so terrified of doing the wrong thing. At the first Sunday-morning Pledge Service I attended in East Garden, for example, I wore my long white church robes, only to discover all the Moons dressed in suits and dresses. I was mortified as only a teenager who is conspicuously dressed can be. I was embarrassed by my ignorance and hurt that no one had offered me guidance to such simple practices. Un Jin stepped in to fill that role, telling me what to expect at family gatherings and church ceremonies.

The Pledge Service was held in the study adjacent to the bedroom of the Reverend and Mrs. Moon. I was amazed at those services to realize that the Moon children did not know the words to the Pledge that I had been reciting from memory since I was seven years old. After the prayer service, the church sisters would bring snacks for the True Family: juice, cheesecake, doughnuts, and Danish. I would serve the Reverend and Mrs. Moon until it was time for us to go to Belvedere at 6:00 a.m., when the Reverend Moon preached his regular Sunday sermon before a gathering of local members.

It was an honor for me as a young woman to be able to hear Sun Myung Moon preach every week. He spoke in Korean, so it was easy for me to follow him. The American members relied on the rough translation provided by his assistants. I wish I could capture what it was about the Reverend Moon’s sermons that touched my heart. It was not that he was especially profound, or particularly charismatic. In truth, he was neither. Mostly he urged us to dedicate our lives to serving God and humanity by becoming moral and just individuals. It was a noble calling. Most of us in that room at Belvedere on Sunday mornings really believed, however naively, that by our goodness alone we could change the world. There was an innocence and a gentleness about our beliefs that is seldom reflected in the denunciations of Unification Church members as cultists. We may have been seduced into a cult, but most of us were not cultists; we were idealists.

While the other Moon children went drinking in New York, Un Jin and I would stay up late into the night baking in the mansion’s kitchen, chatting in Korean. Un Jin was a wonderful cook and a generous spirit, sharing her chocolate chip cheesecakes and homemade cookies with the security guards who had an office in the basement of the mansion.

The church members who composed the household staff were more accustomed to taking orders than gifts from the Moon children. The True Family treated the staff like indentured servants. The kitchen sisters and baby-sitters slept six to a room in the attic. They were given a small stipend but no real salary. The situation was little better for security guards, gardeners, and handymen who took care of the Moon properties. The Moons’ attitude was that church members were privileged to live in such close proximity to the True Family. In exchange for that honor, they were ordered around by even the smallest of the Moons: “Bring me this.” “Get me that.” “Pick up my clothes.” “Make my bed.”

Sun Myung Moon taught his children that they were little princes and princesses and they acted accordingly. It was embarrassing to watch and amazing to see how accepting the staff were of the verbal abuse meted out by the Moon children. Like me, they believed the True Family was faultless. If any of the Moons had complaints with us, it must reflect not on their expectations but on our unworthiness. Given that mind-set, I was especially grateful for Un Jin’s kindness. She never acted superior toward me; she seemed to like me for myself.

In Jin disapproved of my friendship with her sister but she could be nice to me herself when it suited her purpose. She came to me once, asking to borrow some clothes so she could sneak out that night. Her own room was next to her parents’ suite in the mansion and she did not want to risk running into Father. Why not? I asked. She told me that recently she had come into her room on tiptoe about 4:00 a.m. It was still dark. She thought she was in the clear, when she saw Father’s shadow in a chair across the room.

As Sun Myung Moon struck her over and over again, his daughter told me, he insisted he was hitting her out of love. It was not her first beating at Father’s hands. She said she wished she had the courage to go to the police and have Sun Myung Moon arrested for child abuse. I lent her my best blue jeans and a white angora sweater and tried to hide how shocked I was by her story.

As much as anything about my new life in the True Family, the antipathy between the Moon children and their parents stunned me. Early on, I was disabused of the idea that this was a warm and loving family. If they had reached a state of spiritual perfection, it was often hard to detect in their daily interactions with one another. Even the smallest children were expected to gather for the 5:00 a.m. family Pledge Service on Sundays, for instance. The little ones were often sleepy and sometimes cranky. The women would spend the first few minutes trying to settle them down. The Reverend Moon would become enraged if our efforts to shush them did not succeed immediately. I remember recoiling the first of so many times that I saw Sun Myung Moon slap his children to silence them. Of course, his slaps only made them cry more.

Hyo Jin never disguised his contempt for Father and Mother. He seemed to consider them as little more than convenient sources of cash. We had no checking account or regular allowance when we were first married. Mother would just hand us money, a thousand dollars here, two thousand dollars there, on no particular schedule. On a child’s birthday or a church holiday, Japanese and other church leaders would come to the compound with thousands of dollars in “donations” for the True Family. The cash went straight into the safe in Mrs. Moon’s bedroom closet.

Later on, Mrs. Moon told me that fund-raisers in Japan had been assigned to provide money for the support of Hyo Jin’s family and that funds would be sent regularly for that purpose. I had no idea how the mechanics of this worked. The money did not come directly to us. In the mid-1980s, money deposited in the True Family Trust was wired to Hyo Jin, and the other adult Moon children, every month. Hyo Jin received about seven thousand dollars a month, deposited directly into the joint checking account we had established at First Fidelity Bank in Tarrytown. The specific source of that money, beyond “Japan,” was never clear to me.

Hyo Jin would go to Mother regularly for large sums of cash. She never said no, as far as I could tell. He stashed his money in the closet of our bedroom, dipping into his cash reserves whenever he headed out to the bars.

I was terrified one evening when he began screaming and throwing things around our room as he prepared for one of his evenings in Manhattan. “I’m going to kill you, you bitch,” Hyo Jin yelled, as he rummaged through his closet, knocking clothes from their hangers and ties from their rack. “What did I do?” I asked apprehensively. “Not you, stupid. Mother. She’s trying to ruin my life.” His money was missing. He assumed Mother had come into Cottage House and taken it in order to curtail his drinking. I was doubtful. I had seen no evidence that either the Reverend Moon or Mrs. Moon tried to exercise any control over their children’s wild behavior.

As I picked up his rumpled clothes, I found a wad of cash on the closet floor, wedged between a pair of shoes. It must have fallen out of a coat pocket. I counted more than six thousand dollars. Hyo Jin snatched the money from my hand, continuing to denounce Mother with a string of profanities as he nearly knocked the door from its hinges on his way out to the bars.

School, as difficult as it was for me, was a haven of sanity compared with the chaos of Cottage House. In English class I memorized lists of vocabulary words with no idea what they meant. In biology class I stared blankly as the teacher spoke directly to me and the class convulsed with laughter at my total lack of comprehension. It was only in math class that I saw a glimpse of the competent student I once was. For those forty minutes we all spoke the universal language of numbers. I was only a sophomore but I was enrolled in a twelfth-grade algebra class that covered material I had mastered in fourth grade in Korea.

I sat with other Blessed Children from Korea at lunch and sometimes studied with them as well. My position as the wife of Hyo Jin Moon lent a formality to our relationship that precluded real friendship. That cafeteria table was just one more place where I did not quite fit in. Two of my Korean classmates came to Cottage House one afternoon to study with me. They asked for a house tour. I showed them the practice room crammed with guitars and amplifiers and drums of the U Band. I showed them the bedroom and my study, where Mrs. Moon had installed a desk and bookcases for me.

“But where do you sleep?” one of the girls asked. “In the bedroom, of course,” I said, realizing too late that they were staring at the queen-sized bed. As members of the church, they knew of my marriage to Hyo Jin Moon, but they must have assumed it had not been consummated. That was not such a foolish assumption, I realize now. The age of consent in New York State is seventeen. Hyo Jin could have been arrested for statutory rape.

My embarrassment turned to shame when one of the Blessed Children turned on the television and an X-rated movie in the VCR came on the screen. I had never even seen Hyo Jin use the VCR. I checked the television cabinet and it was full of similar movies. Hyo Jin only laughed later when I confronted him about the pornographic films. He liked sexual variety, he said pointedly, in his life as well as in his entertainment. I should know that he could never be satisfied with one woman, especially a girl as prim and pious as I.

Hyo Jin even went to his mother to complain about my lack of sexual maturity. She called me to her one day to discuss my wifely duties. It was very awkward. I had trouble following her euphemisms about being a lady during the day and a woman at night. We must be friends to our husbands in the day but fulfill their fantasies at night, she said; otherwise they will stray. If a husband does stray, it reflects a wife’s failure to satisfy him. I must try harder to be the kind of woman Hyo Jin wants. I was confused. Hadn’t Sun Myung Moon chosen me for my innocence? Was I now expected to be a temptress? At fifteen?

I was beginning to see the truth: our marriage was a sham. Hyo Jin had gone through with the wedding, but he had every intention of living the life he had before. I suspected that Hyo Jin was having sex with the hostesses at the Korean bars he frequented, but I had no proof. When I would ask him what he did when he stayed out all night, he told me that it was impudent of me to question the son of the Messiah. I would lie awake in our bed, imagining that I heard his car, when it was only the sound of the wind.

Soon after our wedding, I had physical proof of his promiscuous lifestyle, but I was too naive to recognize it. Within weeks of our marriage, painful blisters began to appear in my genital area. I had no idea what had triggered the eruption of such terrible sores. Perhaps it was a normal reaction to sexual intercourse. Perhaps it was a nervous reaction.

It was no such thing, of course. Hyo Jin Moon had given me herpes. For years I would have to undergo laser treatments and apply topical ointments whenever the rash erupted. I spent one entire night soaking in a warm tub after a laser treatment inadvertently burned the delicate skin in the affected area. Hyo Jin watched me crying in agony in that tub that night and never told me the true source of my pain. It was years before my gynecologist told me explicitly that I suffered from a sexually transmitted disease. I needed to know, she said, because in the age of AIDS, Hyo Jin’s adulterous behavior was not just a risk to his soul. It was a risk to my life.

In the spring of 1982, though, I knew only that Hyo Jin did not love me. Within weeks of our wedding, he told me we should go our separate ways before we ruined each other’s lives. “We can’t,” I replied, stunned and tearful. “Father matched us. He says we must live together. We can’t just split up.” That was when Hyo Jin told me that he had protested my selection, that he had never wanted to be matched to me, that he went through with the wedding only to please his parents. He had a girlfriend in Korea, he said, and no plans to give her up.

I don’t know which was more painful, his infidelity or the delight he took in flaunting it. Had he wanted to be discreet, Hyo Jin could have spoken to her privately. Instead he took sadistic pleasure in telephoning her in front of me from the living room in Cottage House. When he wanted to isolate me in East Garden, he spoke English to his friends and family. When he wanted to hurt me in my home, he spoke Korean to his girlfriend. “You know who I’m talking to, so go away,” he would laugh, before loudly proclaiming his love for the girl at the other end of the telephone line.

Several weeks after our wedding, Hyo Jin left for Seoul with no word to me on why he was going or when he might return. He did not come home for months. He was not there the morning I suddenly became ill during a birthday celebration for one of his younger siblings. My mother helped me from the table, knowing instinctively what I did not even suspect. I was pregnant.

I responded to my pregnancy like the child I was. How would I finish high school? What would the other kids say? The larger questions, about my lack of preparedness for motherhood, about the perilous state of my marriage, were too difficult for me to face. It was easier to worry whether I could make it through the school year without my condition’s becoming apparent to my classmates.

The news of his impending fatherhood did not bring Hyo Jin rushing home from Seoul. He never even called or wrote to me. I called him once, only to have him chastise me for wasting Father’s money. He hung up so abruptly that the Korean operator had to tell me my call was disconnected. I felt as though I had been slapped. When he did call to talk about the pregnancy, Hyo Jin spoke to Peter Kim, not to me. I was about to enter the kitchen one morning in the spring when I heard Peter Kim relaying to my mother the substance of that telephone call. I held my breath while I eavesdropped. What could possibly happen next? Even I was not prepared for what I overheard.

It was Hyo Jin’s position that since we were not legally married, he was under no obligation to me, he had told Peter Kim. He intended to marry his girlfriend, who was not a member of the church. If the Reverend and Mrs. Moon wanted to take care of me and the baby, that was their choice. He wanted out. I was very scared, listening to Peter Kim and my mother, who said very little. Could Hyo Jin do this? What would happen to me and my baby? How could Hyo Jin break apart what Sun Myung Moon had joined together?

Hyo Jin soon returned from Korea and, without a word of apology or explanation to me, moved out of Cottage House. “I’m sure Father will take care of you and the baby,” he said coldly. He even had the temerity to call to say that he would come by later that night to retrieve a prescription to treat his herpes. I was so incensed that before he arrived I unscrewed every light bulb in Cottage House so that he would have to stumble his way to the medicine chest. What satisfaction I took in my childish prank was short-lived. He was gone and I was alone and pregnant.

I had no idea where he was. It was not until later that I would learn that he had used the money we were given as wedding presents to pay for his “fiancee’s” airfare to the United States and to rent an apartment for the two of them in Manhattan. On his return to East Garden from Korea, he had told the Reverend and Mrs. Moon that he intended to live with the woman he chose. Neither parent made any attempt to stop him. I always believed that the Moons were afraid of their son. Hyo Jin’s temper was so volatile, his moods so irrational, that the Reverend and Mrs. Moon would go to any lengths to avoid a confrontation with him.

Instead, True Parents sent for me. I bowed before them, remaining on my knees, my eyes downcast. I hoped they would embrace me; I prayed they would reassure me. On the contrary, the Reverend Moon lashed out at me. I had never seen him so angry; his face was twisted and red with rage. How could I have let this happen? What had I done to so displease Hyo Jin? Why couldn’t I make him happy? I did not lift my head for fear Sun Myung Moon would strike me. Mrs. Moon tried to calm him, but Father would not be appeased. I had failed as a wife. I had failed as a woman. It was my own fault Hyo Jin had left me. Why hadn’t I told Hyo Jin that I would go with him?

My own thoughts made little sense. How could I go with him? To live with him and his girlfriend? I had high school to finish. I was frightened by the Reverend Moon’s fury but I was also hurt at being wrongly accused. Why was it my fault that Hyo Jin had taken a lover? Why was I to blame because the Reverend Moon’s son did not obey his father? I knew better than to voice these thoughts, but I had them just the same. It was my lot to humble myself before them, to take their abuse, and to speak only when spoken to. Tears burned my cheeks. I stayed on my knees, silent before the Lord of the Second Advent, but I seethed inside at the injustice of his attack on me. “Get out,” he finally screamed, and I scrambled to my feet. I ran all the way back to Cottage House, blinded by my tears.

I felt utterly abandoned. My mother was no use to me. She was trapped in the same belief system that ensnared us all. If Sun Myung Moon was the Messiah, we must do his will. None of us was free to choose. It was my fate to be in this situation. I had to deal with it as best I could. Only God could help me. In my room at Cottage House, I wept and prayed aloud for God not to forsake me. If he could not ease my pain, I prayed he would make me strong enough to withstand it.

I was full of self-loathing for my weak tears. I was ashamed to cry in front of God. He had chosen me for this holy mission and I was not only failing him, I was surrendering to self-pity. I prayed for God to strengthen my faith, to grant me the humility to accept the suffering he sent me.

On one such occasion, I had not realized that my mother was downstairs, listening to my prayers. When I came down, her eyes were as red as my own. It must have been hard for her to watch her daughter suffer so and feel powerless to help. I am only guessing at her emotions, though. We never spoke of our feelings. Perhaps we feared that if we acknowledged one another’s pain, we would only be driven deeper into despair.

I was learning early in my marriage that hiding my feelings would be the key to self-preservation. I spent my days going through the routines of a seemingly carefree schoolgirl and my evenings on my knees in desperate prayer. Every afternoon that spring, I paced around the wide circular driveway in front of the mansion, trying to sort out my thoughts. One of Sun Myung Moon’s early disciples joined me one day as I walked. No one in the Moon family had offered me any comfort. I was only assessed blame, which I was duty bound to accept. The church elder circled the pavement with me, urging me not to worry. My misery could harm my baby, he warned. Hyo Jin would come to his senses, he promised. I was embarrassed that my humiliation was such public knowledge, but I was grateful for the kindness of a respected elder.

That spring my brother Jin had finally come from Korea to join Je Jin at Belvedere. He had barely arrived when this crisis erupted: One afternoon the Reverend Moon summoned In Jin, Jin, and me to his room. “Should we throw Hyo Jin out of the family for what he has done?” the Reverend Moon asked us all, though it was clear that he expected only his daughter. In Jin, to answer. In Jin argued that Hyo Jin was young and wild but that he would listen to reason, that he would come home in his own time. It would be destructive for the church, as well as the True Family, to disown the heir apparent to the Unification Church. Jin agreed. I said nothing.

If Hyo Jin returned, Father said, we must all forgive him and help him adjust to his responsibilities. I, especially, must hold no grudge, the Reverend Moon instructed. He conceded that this was a difficult time for me but said I owed it to the baby to pray for God to soften my heart toward my husband. He and Mrs. Moon would get Hyo Jin back. The rest of us were to welcome him warmly on his return.

The next morning Mrs. Moon took one of the prayer ladies with her to the Deli, a diner in Tarry town. What I did not know was that Mother had arranged to meet Hyo Jin’s lover there. She arrived defiant, intending to fight for my husband. She told Mrs. Moon they would not let religion stand in their way, that Hyo Jin was prepared to leave the Unification Church for her.

I was told it was a spirited performance. But his girlfriend left that diner with a full wallet and an airplane ticket to California. The Moons paid her off, sending her to Los Angeles in the care of a Korean woman whom she would soon ditch in order to make her own way in the world.

The Moons were very pleased with themselves. They had gotten Hyo Jin back home to East Garden. Never mind that they were ignoring the underlying issues that made him leave in the first place. Never mind that he was returning even angrier than when he had left. By all appearances, everything was back to normal, and appearances were everything to Sun Myung and Hak Ja Han Moon.

One morning soon after Hyo Jin’s return, I came to greet True Parents at their breakfast table. I was surprised to see that they had been joined by the Buddha Lady, the Buddhist fortune-teller who had blessed my match to Hyo Jin the previous fall in Seoul. Mrs. Moon urged her to tell us what the future held for Hyo Jin and me. “Nansook is a winged white horse. Hyo Jin is a tiger. This is a good match,” she said. “Nansook will have a difficult time in life but her fortune is very good. Hyo Jin’s fortune is tied to hers. He can be great only if he sits on Nansook’s back and together they fly.”

Mrs. Moon was so pleased by the Buddha Lady’s optimistic forecast that she went out and bought me a diamond-and-emerald ring — the fortune-teller had told her that green was my lucky color. A few days later the Buddha Lady came to see me secretly at Cottage House. “Please remember me when you are a very powerful woman,” she said. “Remember the good fortune I saw ahead for you.”

What lay ahead for me was nothing like what the Buddha Lady foresaw. Hyo Jin was furious that his parents had interfered in his love life, but he was also a realist. He was in no position to follow his lover to California. He had no money, no job, no high school diploma, no means of support besides his parents. In the end, Hyo Jin was all talk. True love paled next to the prospect of being cut off from Father’s money.

Hyo Jin and this girlfriend would continue to correspond for years. He often left her love letters out in the open for me to find. When Hyo Jin learned that she had moved in with a new lover in Los Angeles in 1984, he was so distraught that he shaved his head.

In the spring of 1982, though, he had returned to Cottage House more angry than heartbroken. The indifference Hyo Jin had felt toward me in the winter had hardened into something much colder, much more frightening. I embodied his lack of choices in life. I represented his dependence on the two people he most needed and most despised in this world: his parents. Hyo Jin Moon would spend the rest of our life together punishing me for it.

Nansook Hong interviewed (with full transcript)

In the Shadow of the Moons book, part 1

In the Shadow of the Moons book, part 2

In the Shadow of the Moons book, part 4

In the Shadow of the Moons book, part 5