#awhalin

Text

Re: dramatically changing 19th century dress silhouettes, thinkin about the time a whaler finally came home from a 4 year voyage and was just like ‘WHAT IS GOING ON’ when reencountering hoop skirts.

67K notes

·

View notes

Text

Lawrence Manner for @focsle !!!!

#going to weather#lawrence manner#art tag#why did i sit there for 40 seconds trying to remember the name of the comic#and my I kept going ‘awhalin’ ‘no’ ‘awhalin’ ‘that’s not it’

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

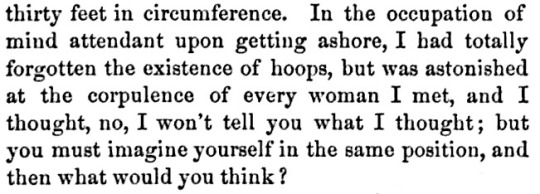

I always talk about how one of my loves of scrimshaw is being able to see the art of Just Some Guy in the 19th c. and this is the latest one I’m charmed by.

I love his face, look at how economical those lines are!

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm so fond of these two 1924 photos taken by William Tripp of the crew of the whaling bark Wanderer because they were clearly taken in the same moment but the fellow in the front second from the right was like 'wait, the cat!'. Or, alternatively, he was holding the cat first and the cat was like 'I'm not sticking around for this'.

999 notes

·

View notes

Text

I never did a long thing about scrimshaw, so it’s time! At 1 am, apparently.

I think scrimshaw is one of the most fascinating material goods to emerge from the history of the American whaling industry (which is the context I’m discussing here, though of course the artform exists across numerous eras and cultures outside this brief blip of nautical history).

It’s one way to see amatuer art that usually doesn’t often survive in other forms. To see the art project of an ordinary man who was bored and needed something to do with his hands. Others were highly skilled craftsman, creating intricate engravings or mechanically expert tools. The most common scrimshaw was images etched on sperm whale teeth. Sometimes those images came from the maker’s own imagination and sometimes they were copied illustrations. Ships & whaling scenes, women, mythical figures, and patriotic symbols make up the bulk of the visual language in those pieces that survive.

But alongside the teeth were all a manner of carved items: canes, candle holders, pie crimpers, children’s toys, sewing boxes, yarn swifts, corset busks. So much bone fashioned into quiet little homegoods. And it’s that contradiction within scrimshaw that fascinates me. The brutality of the industry, this ivory from an animal that frankly died terribly, that’s then softened into a little domestic item. An object that could have hours to years of work put into it. Some were made to be sold but many were made as gifts. In the long stretches of boredom at sea, in the lull between back-breaking work and life-threatening terror, scrimshaw gives a window into where the minds of these men continually turned. It shows where their hearts were and what they were holding on to over all the years they spent adrift in saltwater and blood and oil. That’s the poetry I see in scrimshaw. Pain and love and longing and creativity and playfulness all bound together in these complicated little pieces that found their way out of the hands of their anonymous makers to preserve a small part of their story.

Some scrimshanders names are known. Frederick Myrick is one of the most well known American whalers, not so much for the scope of his life (of which little is known) but for his scrimshaw. Born in Nantucket in 1808, he first went whaling in 1825 on the Columbus and then again on the Susan 1826-29. In the last few months aboard the Susan, Myrick engraved over 30 sperm whale teeth, all depicting the ship he was on (though there are a handful that depict other vessels). He signed and dated nearly each one. These pieces are often referred to as ‘Susan’s Teeth’ now, and when one comes up at auction it’s not unusual for it to sell for six figures.

Many of the teeth Myrick scrimshawed included an inscribed couplet of his devising: A dark wish for luck that succinctly gets at the violent and unstable heart of American whaling.

“Death to the living, long life to the killers

Success to sailor’s wives, and greasy luck to whalers”

Sometimes large scenes were etched on panbones as well.

Moving from scrimshaw on teeth and jawbones, pie crimpers are some of the more common sculptural items. Popular motifs included animals (dogs, snakes, and unicorns/hippocampus are big), body parts (mostly clenched fists or lady’s legs), and geometric designs.

Others were more mechanically complicated, such as automatons and children’s toys with moving parts and gears. Here’s one of a small rocking sailboat, perhaps made for someone’s child or younger sibling.

Sometimes a particular creative fellow created something more eccentric, like this wild writing desk kit fashioned out of a carved panbone and sperm whale teeth.

Another frequently scrimshawed object was a corset busk that would be slid into the front of the garment in order to maintain the posture. A rather private item compared to others. And one with a very on-the-nose message of wearing close to one’s heart the memory of someone who’d be gone for 3-4 years, who might never come home again. On some level, so many of these daily objects whispered ‘forget me not’, ‘think of me while I’m gone’.

There’s something tender to all the various domestic items that were fashioned on the job so long and far from home, but it’s the yarn swifts that really captivate me. They were one of the most complicated pieces of scrimshaw to make, with over one hundred different pieces that would have to be carved. It could take someone the length of the voyage (2-4 years) to complete a single one. Unlike teeth which were comparatively very quick to make and were frequently intended to be sold, it’s very unlikely that a swift was made with the aim of selling it because of the significant labor that went into it. They were almost certainly all gifts, and very special ones at that. Every time I see one I can just feel the love towards its intended recipient radiating off of it.

Scrimshaw captures a specific snapshot of a moment in time. On a broader scale it’s a surviving reminder of a bloody industry that flared up and winked out, preserved in the form of a long-lost ship and the spout of a long-dead whale inked on a yellowing tooth. But that snapshot also reveals the emotional world of the men who were caught up in such an industry: what they valued, what they thought about, what they missed, and what they wanted to be remembered of them.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Man...they're so young. Every day I'm reminded how young the majority of whalers were.

1925, photographed by William Tripp

#this is 20th century so it was more common to see older men aboard#but at the peak of the industry most were under the age of 25#awhalin

320 notes

·

View notes

Note

have you written anything about tattoos? is that relevant? don't know how your niche lines up with generic "sailor" tradition, but wikipedia simply says on knuckle tats that deckhands may get "HOLD / FAST" as a charm to support their grip on rigging, and i thought that was kind of cute.

I haven't written anything myself, mostly cos if you throw a stick out in the internet you'll find any number of articles about the symbolism of sailor tattoos, like hold fast and pigs and roosters and swallows and all that!

In my narrow window (the middle decades of the 19th century), I don't see tattoos mentioned all too often, compared to late 19th and throughout the 20th century where they became more common. For instance, this register of seaman's protection certificates (which are admittedly limited in the scope of things, since they're only from a few specific ports) from 1796-1871 rarely list tattoos as distinguishing marks, beyond the odd mention of being marked with an inked anchor, eagle, or letters here or there.

Here's a neat jstor article (if you have any more of your 100 free monthly articles to read with a google account) that goes into late 18th-early 19th c tattoos that has some tables and visuals. The research was also done using seaman's protection certificates, with the following stat:

"The SPC-A records start in 1796 and include tattooed men born as early as 1746. There were 979 tattooed men out of a total of 9,772 men whose records survive from 1796 through 1818.26 These men were marked with a total of about 2,354 separate designs."

So, not a large number, but also 10% isn't insignificant. The protection certificates while a reliable source, also only describe the man in one specific moment. I'm sure a few of those men who just have their moles and scars and crooked fingers listed eventually picked up a tattoo or two in their time.

Most journal keepers perhaps didn't think it important to mention who had tattoos or what of, though the typical motifs of anchors, nautical stars, girls, religious & patriotic imagery, etc. were certainly a part of the visual language at this point. Whaler William Abbe who sailed in the 1850s, devoted considerable attention to describing the physical appearance of some of his shipmates. In one instance, he wrote about the tattoos of one 'Johnny Come Lately' or 'Jack Marlinspike' (Real name, John Hewes of Buffalo NY)

'from beneath this cap his face looms out - while beneath supporting his comical head is a bare neck and breast — hairy + brown —the upper timbers to a stout hull of a boat that boast a pair of arms all covered with India ink tattooings — the figure of American Liberty — Christ on the cross — an American Tar holding a star spangled banner in one hand + a coil of rope in the other — a fancy girl — + anchors, rings, crosses, knots, stars all over his wrists + hands — the memorials of different ports he has visited — for Jack has been in all kinds of vessels from a man of war to a blubber hunter — + has consequently been to many ports.'

From the logbook of another whaler who sailed in the early 1840s, James Moore Ritchie, he had a page of his drawings with prices included. This potentially may have been a tattoo flash sheet for his shipmates:

American whalers also noted the tattoos of indigenous people who had signed on to whaling vessels, particularly in the South Pacific. William B. Whitecar, whaling in the 1850s wrote: "Several New Zealanders in the respective crews of these vessels attracted my attention from the tattooing on their bodies" making mention of "figures on their face and breast".

I'm too sleepy to have a conclusion lol. Tattoos! They existed! Though perhaps not as ubiquitously as the pop culture sailor designs would imply, at least prior to the late 19th c.

209 notes

·

View notes

Text

From the diary of Mary Chipman Lawrence, who accompanied her husband Captain Samuel Lawrence on the whaler Addison, 1856-60. Her young daughter Minnie was with her as well, and on July 18th 1859 it was her birthday and they celebrated it on board:

This is Minnie’s birthday—eight years old. I told her a month ago that when it was her birthday, I would make a treat for her in the evening and she might invite all the officers to partake with her. So she has ever since been looking forward to it as a great event. Saturday I made preparation, and I was fortunate in doing so, for I suffered exceedingly Sunday night and for the greater part of this day with a gathering at the roots of my tooth. I was able to get up, however, and prepare the treat for her. We set the table and called the officers down about half-past 7 P.M. Minnie was so happy she hardly knew what to do with herself, and I think we all enjoyed it pretty well. The officers all united in saying that they had not sat down to such a table since they left home. The treat consisted of a plate of sister Celia’s fruitcake, two loaves of cupcake frosted, two plates of currant jelly tarts, and a dish of preserved pineapple, also hot coffee, good and strong, with plenty of milk and white sugar. After we had finished there was ample supply left, which was sent into the steerage for boatsteerers, etc.

Minnie arose this morning about four o’clock to look at her presents. She had a box of little notions, a book, and a pocket handkerchief from Mrs. Brayton; a pair of china vases from Mary White; two packages of paper dolls, a book, and a package of drawing cards from Helen Whitney; an ivory shuttle and a half dollar from her papa; and a bottle of cologne, a toothbrush, and a quarter of a dollar from her mamma. Not of much value, but they were all very pleasing to her.

#there’s some really cute shit with Minnie#most of the fellows on these ships seem very endeared to her#awhalin#mary lawrence

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Some of these dudes press fish fins in their journals like flower petals and it’s something.

Love the aesthetic notions people have of Victorian-era journals of like, a lady pressing delicate little natural mementos between the pages and then you get one from a whaleman and it’s just……..mangled flying fish fins.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

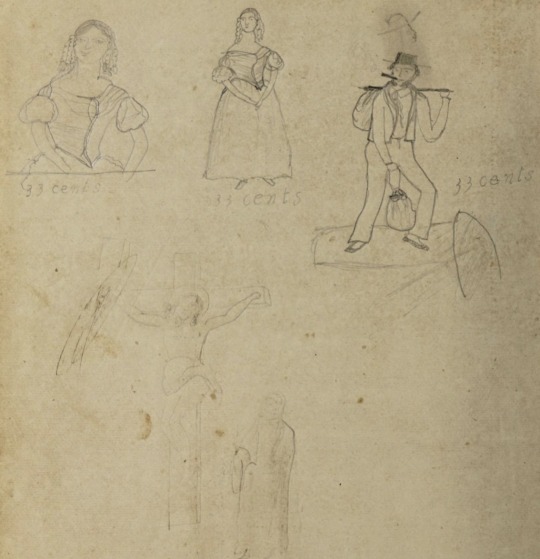

Something about this little note a whaler added in the margins of his journal gets me.

224 [days out]

My book is very damp ink spreads.

Can’t really articulate why but I think it’s something about…the process of reading it now in all its spreading ink, and seeing this little complaint he penned in the moment to explain the ink quality. It‘s a concrete physical link to a little moment in time when this book was new (yet damp) in a fellow’s hands 170 years ago.

#cooper chappell#awhalin#all the bits in these journals where they’re basically like ‘OH I CAN’T WRITE ANYMORE GOT TO GO THERE’S WHALES’#or ‘i want to write more on this but I’m so tired I got 2 hours of sleep’#are the ones that get me the most because of that specific tie to a moment#and to a real person who u know…gets tired and hungry and what have you

262 notes

·

View notes

Text

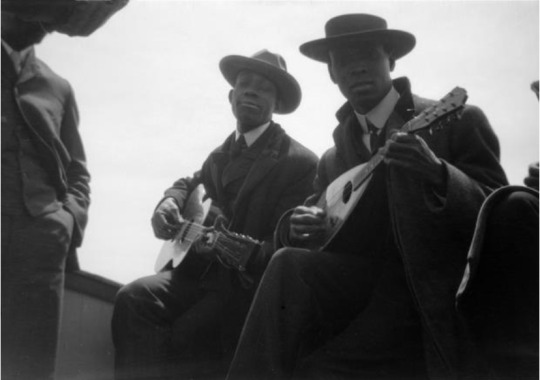

Music on Whaleships

Because how else will you power through the boredom AND the horrors!?

Two men aboard the Wanderer, photographed by Pardon B. Gifford in 1906 (New Bedford Whaling Museum)

Music featured quite frequently on whalers, though not necessarily in the same way as it might on a merchant vessel. The quintessential musical contribution of sailors—the sea shanty—didn’t hold as prominent a place aboard a whaler as it did on other types of ships. Some captains were particularly strict about keeping noise down while cruising to prevent gallying any nearby whales. Shanties were also less necessary for performing the work: Whaleships tended not to carry a great deal of sail, had a lot of hands aboard available to handle it, and were quite leisurely in their pace as they lolled around the globe for years at a time. This was unlike merchant ships that tended to have smaller crews, larger ships, and tighter schedules, all for which shanties were used more often to coordinate that work effort.

However, music was still vital to maintaining good morale during a whalers' work that was, in turns, extremely demanding and dangerous, and extremely dull and mind-numbing. Both of which could really plague a fellow's soul if there was no relief. A panacea for a whaleship's ills, music rang out in the fo'c'sle during idle hours, was sought out during shore leaves, was copied down in remembered songs in the backs of men's journals, and any fellow who hazarded to pick up an instrument or lift his voice was a prized member of the crew.

Read on, under the readmore, since this is also quite a long one with many a photo, journal entry, recorded music, and whalers' original written songs! I really REALLY enjoyed pulling this one together.

Even though they weren't as utilized, there were still occasions when shanties burst out on deck. Greenhand William Abbe of the Atkins Adams (1858) recalled them first being used several months into the voyage. This speaks to the fact that shanties weren't a regular part of whaling work, but rather an instance of one shipmate finally venturing to include them:

“We began to sing shanties last night in hauling aft sheets or bowsing on halliards — Jack leading in 'Johnny Francois' + 'Katy, My Darling' and all hands taking up the refrain + pulling with a will. This pleased the Mate who told us that pretty well for the first time that he liked to hear us make a noise—as it showed that Jack —not Allegany [surname of a crewmate on board] — but any one of us was awake. He laughed—waved his hands— + cried out 'that’s the way sailors'.”

youtube

Johnny Francois, aka Boney

They were later "obliged to avast singing + haul away without the "Shantie" as the crew’s singing was so "ludicrous" that they were all laughing over it rather than effectively hauling. But even if shanties weren’t often used aboard the Atkins Adams to set the pace of the work, they still featured during downtime in their watches:

“Jack leading sung the watch out in Shanties 'Johnny Francois' 'Santa Anna' 'Katy, My Darling' +c. Mr. Gorland + Tripp came forward and joined us. It was very cold and wet — but our singing warmed our hearts while we were free from the spray and warm from mutual contact.”

On whaleships, shanties were more frequently employed—though still inconsistently—during more demanding tasks such as weighing anchor or working the windlass to haul up blubber.

While greenhand John Perkins’s ship, Tiger, was lying at anchor at the Hawaiian islands in 1845, he mentioned hearing another whaling crew strike up a shanty upon leaving:

“When called this morning we heard the Neptune’s crew weighing anchor to the tune of ‘Tally hi o you know.’ After breakfast our watch went ashore on liberty”

youtube

Tally-I-Oh

Music was also greatly sought out during whalers’ shore leave. Thomas Nickerson, cabin boy of the ill-fated Essex, 1820, wrote about a dance hall in Talcahuano that he was quite unimpressed by, but his other shipmates enjoyed tremendously.

"There we found a few young women seated around the hall on wooden stools, and playing off some Spanish airs upon their guitars to dance by. There did not seem to be either melody or music in their touch, but after such an interval of confinement our men were ready to dance to anything had it even been a corn stalk fiddle. With their guitars were an accompaniment of an old copper pan used as a tambourine. To this music did our men dance apparently with as much satisfaction as though it had been the finest music in the world.”

Music was also one of the first ways whalers and locals at various ports of call built camaraderie between each other, where potential language barriers were no object if someone had along with them a fiddle (and maybe some alcohol). Such an interaction was recorded by Albert Peck, greenhand on the Covington that stopped in Guam in the 1850s:

"Having our fiddler with us, we went from one hut to another giving them a tune at each, which would please them very much, and to show their appreciation of it they would produce a bottle of aquadiente [Aguardiente] or brandy, and treat us to a glass which would consist of a coconut shell, until it became evident that this would not do if we intended to walk to the town, as before long we should be incapable of walking anywhere. So we started for the town."

Whaler-made fiddle c. 1835-50, inscribed with the name Daniel Weeks. (New Bedford Whaling Museum)

But liberty always came to an end. When the Tiger departed Hawaii 10 days later, Perkins noted that they were too glum to accompany their leaving with a shanty:

“We weighed anchor without a song all feeling to bad at departing from summer islands to the cold Norwest sure of hard labor, absolute suffering & danger.”

Amidst that hard labor, absolute suffering, & danger, music served an essential function of bringing in levity and acting as a pressure release valve aboard.

Clifford Ashley, who joined the bark Sunbeam in 1904 on part of her voyage for research, described the music of his dog watch:

"Two misfit concertinas every night sent up their dismal wail to a tune that never varied, often keeping time with the strokes of a couple who pounded up hard bread in a canvas bag to be mixed into a molasses mush for their watch."

A whaler's concertina, c. 1850 (Nantucket Whaling Museum)

Any man who had a bit of a voice or could play a bit of an instrument quickly became a favorite among the crew, even if he only knew one song. Foremast hand William Stetson, of the Arab (1850s), was delighted when a new man they shipped aboard during a provision stop had some faint musical inclination.

“in the dog watches we enjoy ourselves very agreeably by stepping off a lively measure to the tune of “roads to Boston” as performed on the violin by Moody, one of those lately shipped at Lahaina. This is about the only tune he can saw off decently, but he is the first that has belonged to the bark this voyage who has made any pretensions to being a fiddler, and consequently the ‘doleful music’ of the skipper’s cracked violin is usually heard in the evening between the hours of five and seven P.M"

youtube

Moody's go-to, Road to Boston.

Even in the absence of an actual musical instrument, crews made do with whatever they could get. William Abbe writes about one such time on the Atkins Adams:

Last night while gamming with F. Willy in the forecastle I was called on deck to help make up a set for a cotillion — being honored as the lady of Curly — we were at a loss for music + were stepping to the hummed air of Johnny the Boatsteerer + the orders of the dancing master — Jack — when Shanghai rushed up from the forecastle + jumping up on the oil cask looked forward of the windlass + squatting his long legs on the cask head began a toot toot on an old tin funnel, followed by Johnny Come Lately on an old tin bread pan for a drum — We greeted our band with shouts — + to the music of our mimic french horn and kettle drum chased up + down + joining hands by partners promenaded with double quick steps round the forecastle deck making the deck ring with our laughter — + the rattling music — both music and steps getting quicker + quicker till Tarpsechorz [Terpsichore] herself would have fled agast — + home belles and beaus would have fainted at the sight —our fun was suddenly interrupted by the order to shorten sail — + our quick stepping was only rivaled by our agility aloft for we reduced sail in unusually short time.

The captain, enjoying their sense of play but finding their makeshift music particularly disagreeable, then came up on deck to give them something to better it:

“Old Man liked the fun but didn’t like the music for Old Woman — brot up on deck a new accordion + calling Charley aft consigned it to him with the injunction to use it well — Charley came forward — delighted— + mounting the spars struck up Fisher’s Hornpipe + the strums sounding through the calm evening animated us till Jack or Molly [a crewmate currently crossdressing for the role] + our barefooted stepping got the whole Ship’s Company in a roar — from the Old Woman to Cabin Boy.”

Crew members of the Charles W. Morgan, 1906, taken by Pardon B. Gifford (New Bedford Whaling Museum)

Sometimes music was a little less favorably received. J.T. Langdon, greenhand on the St Peter, 1840s-50s, had brought his fiddle aboard to entertain himself, and at one point taught the Captain how to play it. On the homeward bound stretch--with his patience with the job and everyone on board strained to the limit--he grumbled about music-making halting getting home quickly:

"There seems to be an little disregard to sailing the vessel on the part of the Captain and the Mate. The 'Old Man' will saw away on his 'old fiddle' and the mate will tinker and the ship goes where she likes. I have sometimes almost cursed the day that I learned the Cap'n to fiddle."

Sometimes, sailing be damned, it was time for an entire musical production, as on veteran whaler John Martin's ship, the Lucy Ann, 1841. He wrote out the Program along with the nicknames of the performers.

"We finished this day with a grand concert given by the whole crew. The audience were sea gulls. The following is the programme of the concert.

Programme

Part 1st

Song. One eyed Riley With chorus by whole crew. - By Chub.

"There was a Sheppards daughter, Kept sheep on yander hill" - by Lightning

Song. I hit her right on her stinking Machine - by Hominy Head

Solo. On Kent Bugle by - myself

Part 2nd

Song. Cant you wont you stay a little longer - by Turpin

"Turkish Lady - Black Leg

Duette with Drum & Fife - Chub & [left blank]

Part 3rd

Song. My dogs eyes makes mince pies - Steward

"Morgan Ratler - Spunyarn

"The Meremaid in three parts by - Hardy

"Trayum with chorus by crew

Part 4th

Song. Kelly the Pirate - King David

"Tally ho - Spunyarn

"Lord Lovell that went strange, countries for to see - Hardy

Solo. on flute by - Young Norval

Part 5th

Song. Fanny Blair - Turpin

"French Lady - Mizen

"All the girls in our town - Steward

Part 6th

Song. So early in the morning, the Sailors love the bottle O. - by Mocho a color'd Gentleman

"Milkmaid - Hominy Head

"Two little sisters walking up the street" - Jersey

Grand Chorus by the whole Crew on Bugle, Drum, Fife, Flute, Violins, Triangles, &c. & wound up by The mate telling us if we did not quit making such a damned noise he would heave a bucket of stinking water over us. Ends the same.

An excerpt of John Martin's above program:

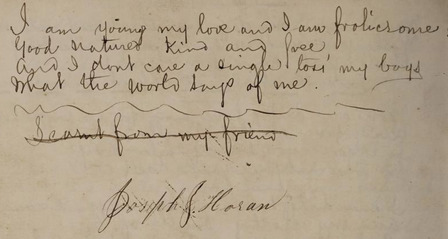

Often, in the backs of journals whalemen would write songs that are still known today. Rolling Down to Old Maui, Blow Ye Winds, Coast of Peru, Homeward Bound, Saucy Sailor, etc. These were learned on the job, or exchanged between crew mates.

From the journal of William Buel of the Wave, 1856, the lyrics to Saucy Sailor which he learned from a fellow greenhand:

"I am young my love and I am frolicsome

Good natured kind and free

And I don't care a single toss my boys

What the world says of me

~~~~

Learnt from my friend

Joseph F Horan"

There's something quite lovely to having a shared thread from their lives into the present. We might be separated by a gulf of over a century, but we know the lyrics to the same songs.

Some whalers composed their own songs, too. I'll close with one written by career whaleman Joseph Dias, when he was captain of the St. George in 1853. He ended his lyrics with the note 'Read and Circulate', so I see it as my duty to do him a small kindness 170 years later by circulating it now.

Paradox

Come all ye shipmates lend an ear

And the truth you soon shall hear

Of the Ship St. George in the zealous sea

Who is raiseing hell it seems to me

—

The way we try to get our grease

So to strike three whales and save a piece

Beside two whales of india ruber

The boatsteerer swore to be slack blubber

—

Very poor advice I freely lend

Of a way I highly recommend

To take a crowbar and punch a hole

Drive in the iron and the pole

—

Hang to your line till all is blue

Either kill him or he kill you

We want a man upon the docket

To go ahead like david Crockett

--

Promoting men at our expense

Takes our dollars with our pence

Besides it throws our work away

This thing For sure will never pay

—

To see the whales was once the cry

They are here where e're you turn your eye

They have raced for rise to sitting sun

Been on a dozen and killed but one

—

To man that’s taught in a bowhead school

Will find himself here but a fool

Read and Circulate

494 notes

·

View notes

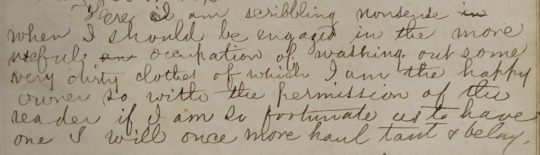

Text

"Here I am scribbling nonsense [in] when I should be engaged in the more useful [and] occupation of washing out some very dirty clothes of which I am the happy owner so with the permission of the reader if I am so fortunate as to have one I will once more haul taut + belay." - William Douglass Buel, whaler on the bark Wave, 1856

Since I am unable to do my heaps of laundry today because someone has inconsiderately monopolized AAAAALL the machines, it's time to write a post about whaleship laundry day to quell my fury!

"A person unused to the sight of the ship would take the Old Lucy Ann for a ready made clothing store, the rigging being hung full of wet clothing" wrote John Martin of his ship on laundry day in 1842.

As always, laundry was a dreaded task but also an absolutely necessary one, especially given how begrimed (or as one whaler put it, 'beshit') things would get on a whaler. William Abbe, a greenhand on the Atkins Adams in 1858, most viscerally described the mess that came from the work:

"To turn out at midnight and put on clothes soaked in raw oil. To go on deck and work for Eighteen hours among blubber—slipping + stumbling on the sloppy decks til you are covered from crown to heel with oil—eating with oily hands oily grub—drinking from oily pots til your mouth and lips have a nauseating oily luster—turning in for a few hours sleep — after wiping off your bare body with oakum to take off the thickest of the oil"

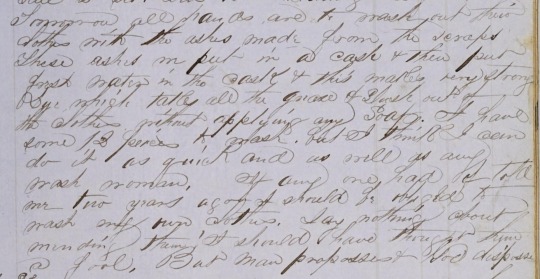

So you gotta clean that shit! 'Clean'. A relative sort of word.

First, whalers soaked their dirty clothes in the communal urine barrel, as the ammonia content of stale urine was one of the few things strong enough on board to start to cut through the grease. Sometimes the clothes would be towed behind the ship afterwards to rinse them, but that wasn't always the case. Rainwater was also collected in anticipation of wash day to have fresh water to rinse with. With this fresh water, a lye was also made using the ashes and crispy blubber scraps come from the trying out process. The deck would be washed in a similar way after trying out a whale, often using a combo of urine, lye, and sand. J.E. Haviland, of the Baltic in 1857 described the laundry work that he had never expected to be doing himself:

"Tomorrow all hands are to wash out their clothes with the ashes made from the scraps These ashes are put in a cask and then pour fresh water in the cask + this makes a very strong Lye which might take all the grease and slush out of the clothes without applying any soap. I have some 12 pieces to wash but I think I can do it as quick and as well as any wash woman. If any one had of told me two years ago I should be obliged to wash my own clothes, say nothing about mending then I should have thought them a fool. But man proposses + God disposses."

Whaling wife Almira Gibbs, who accompanied her family (Captain and young son) aboard more than one whaler had her own recipe for soap, despite Haviland's assertion that it wasn't necessary:

"1 lb castile soap

1 1/4 lb soda

6c worth borax

add 5 pts water and let it simmer till it is all dissolved, take it off and add 9 pts water and let it cool."

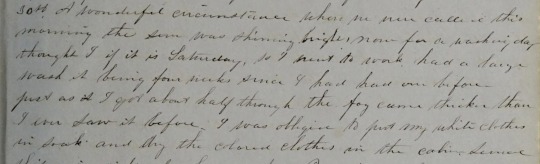

Whaling wives aboard also complained about laundry and the difficulty of doing it aboard ship. The moldering of clothes in such a damp environment, the constant roll of the vessel sometimes overturning one's tub or making ironing dangerous, having to wait for rainfall for fresh water, and a sunny day for actually performing said wash, were constant features in wives' laments. Mary Lawrence, aboard the Addison in 1860 sarcastically wrote about her laundry attempt thwarted by the weather one July.

July 30 A wonderful circumstance. When we were called this morning, the sun was shining bright. “Now for a washing day,��� thought I, “if it is Saturday.” So I went to work; had a large wash, it being four weeks since I had had one before. Just as I got about half through, the fog came thicker than I ever saw it before. I was obliged to put my white clothes in soak and dry the colored clothes in the cabin.

She also mentioned her young daughter Minnie who "took her little tub and washed her dog's bedclothes, for Jip has had a bed all the season that had to be made up like anybody's bed".

Sighting whales at any point would also put an interruption to the wash. This photo taken aboard the Sunbeam by Clifford Ashley in his brief 1904 research trip shows men hoisting up the whaleboats after taking a small whale, their Sunday laundry still hanging between the davits.

I'll close with whaling wife Mary Brewster's description of a wash day following the trying out of a whale on her husband's ship Tiger, one winter day in Magdalena Bay 1847.

"Calm pleasant weather. Employed in sewing till 4 this afternoon, when I went on deck, where I found every part, and everything about, very nice and clean. The sailors all washing up their dirty clothes, both trypots full boiling in ley [lye] and the rigging hung full. A few garments floating which had taken flight overboard to save washing. All presented a lively spectable and I could say with all hands, farewell to Greybacks [lice]."

425 notes

·

View notes

Text

Medicine Aboard A Whaler

I answered an ask about this some years back that was...a few paragraphs long and was before I learned that some people have the stamina and desire to read 3k+ word whaling essays from me. So if ye count yourself among them, here you go!

---

On August 21st, 1870 aboard the whaleship Sunbeam, two-time whaler Silliman Ives found himself ill with a condition “very akin to mumps, with the exception of the swelling”. It prevented him from opening his mouth, and he dreamed of the days when such an action was possible.

“I never really appreciated the luxury of a good gape before. When a fellow cannot open his mouth to any greater extent than the width of a lead pencil, gaping is not a success to say the least. And then anything in the way of a sneeze is entirely out of the question, unless you are prepared to part company with the top of your head at very short notice. A ship is a hard place to be unwell in. So long as one is in good health you can get along nicely. But if you are sick the only place where you can find sympathy is in the dictionary. And then too the remedies at hand are limited in number and obsolete in use. Your medicine chest is filled with medicines in use a hundred years ago, but which modern pharmacy has dispensed with to a very great extent. Calomel and castor oil and such like delectable doses. There is no question about it. A whale ship ought to have a surgeon, and the law should oblige such vessels to carry them. When I get into Congress I shall introduce a “Bill” to that effect.”

As Mr. Ives noted, American whaleships went without doctors aboard even when the work was rife with injury and illness, and often quite far from access to any kind of care ashore. On British whalers it was required by law for a surgeon to be signed on for the voyage—Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was one on a voyage bound for the Arctic and apparently fell in the water so many times that the crew called him the 'Great Northern Diver'. However on American whalers—which dominated the industry—a doctor was seen by the agents as an unnecessary expense. There was the captain, the carpenter, and folks who could mend sails. Together, that makes one whole doctor! Right?

Read on, to see how they fared.

1845 whaleship medicine chest from the collection of the New Bedford Whaling Museum.

Joan Druett, in her book Rough Medicine highlighted some really fascinating things that came as a result of this, ranging from men who had scars that healed in a herringbone pattern because they were mended like canvas, to this wild tale about an amputation performed between a captain and mate at gunpoint:

“Another stirring tale told is of a Captain Coffin, who was hurt so badly in a whaling accident that it was obvious his leg would have to go. Being the master, the medic, and the patient all at once, he knew the situation was complicated, but he was more than equal to the task. He sent for his pistol and a knife, saying to his mate, “Now, sir, you gotta lop off this here leg, and if you flinch—well, sir, you get shot in the head.” Then he sat as steady as a rock while the mate went at it with the knife, holding the pistol unwaveringly until the operation was completed. No sooner was the stump wrapped up and the leg cast overboard than both men fainted.”

It was the captain's responsibility to provide medical treatment. Often without training himself, he was simply given a medicine chest full of numbered tinctures for various treatments. Those tinctures were a mix of chemical and herbal compounds, some which are still used holistically today and some that you.....absolutely want nowhere near your body. Epsom salts as a laxative, laudanum for painkiller, St John's wort for bruises and burns, mercury for syphilis, rosemary as an antiseptic, lead acetate as an anti-inflammatory, arrowroot for dysentery, henbane for insomnia, and on it goes from the innocuous to the dangerous.

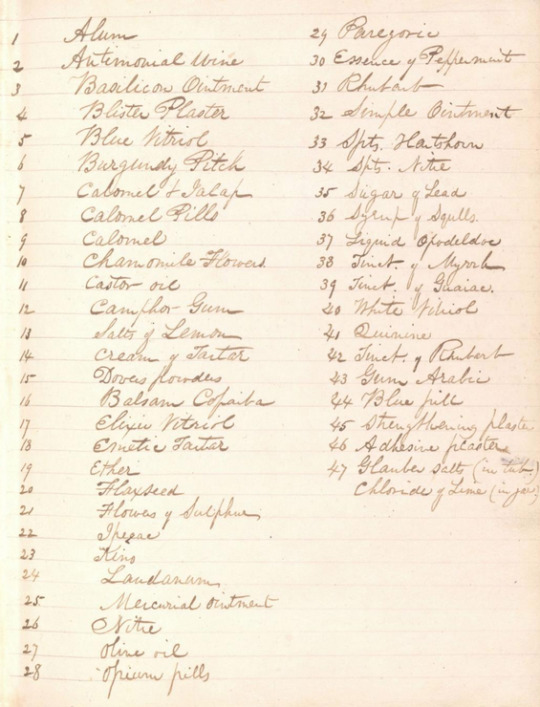

John B King was a rare doctor aboard a whaleship, sailing on the Aurora out of Nantucket in 1837. He wasn’t hired as a doctor though; for reasons unknown he initially obscured his identity and joined simply as a foremasthand until his skills were revealed and he became the ship’s doctor. On that voyage he kept a book of the medicines he used.

John King’s medicine list, from the collections of the Nantucket Historical Association.

In addition to dosing medicine, the captain would also be responsible for setting broken bones, stitching wounds, and amputations. Benjamin Boodry, who had been whaling since the age of 13 and by 1856 was captain of the Fanny described instances in which he had to tend to his crew.

“At 2 o clock a cask of watter rooled away in the Bluber room and one John Haggerty tryed to stop it and got his leg broke just above the Nee there was another chance to show my surgical skill set it splinted it and bandaged it.”

“McKee fel from the Main Topsail yard on deck bled him in both arms he came to some broke his arm and leg and badly bruised”.

Fortunately for McKee, his accident happened off the coast of Faial. The captain sent for a doctor ashore to examine him. He was advised to leave McKee in the Azores where he could receive more proper rest and treatment. But if land was a long way off, people had to make do the best they could.

Some captains had a better bedside manner than others. Where Silliman Ives felt terribly neglected in his illness, William Abbe of the Atkins Adams, 1859, had quite a different experience. He turned to the captain for help with a painful swelling on his hand that eventually grew so bad he was unable to use it.

“The captain was extremely tender in his treatment of my hand, pouring on laudanum to relieve the pain, lancing with caution and as tenderly as could he and using every means in his power to make me comfortable—washing my hand thrice a day with warm water and cutting away dead skin, pressing out matter in a manner that gained my affection + respect. Mrs. Wilson sent me preserved meats, pickled oysters, cake, buttered bread and seconded her husband in all his care. I felt a great deal of respect for both these kind people + shall repay it when I can […] The Cap treated us all with a care + skill that surprised me — I supposed that we should be left to take care of ourselves—the case in many ships, but we were not only cared for but allowed to stay below until we thought fit to return to duty.”

Mrs. Wilson--the captain’s wife--stepping up to help was not so unusual. Often whaling wives also found themselves taking on the role of doctor. All throughout July 1846, Mary Brewster was busy tending to the ailments of the crew aboard the Tiger.

“The last part of the day I have spent in making doses for the sick, in dressing some hands and feet, 5 sick and I am sent to for all the medicin. I am willing to do what can be done for any one particularly if sick for in whaling season a whaleship is a hard place for comfort for well ones and much more sick men.”

She reported that all her patients recovered, with the exception of a young man with a liver complaint beyond her immediate treatment.

Other times, other members of the crew served as de facto doctors as well. One such man was veteran whaler John Martin aboard the Lucy Ann 1842. In addition to being a skilled watercolorist, he also had a knack for bloodletting and tooth pulling. Often he made note of his ministrations in his journal:

“Blistered Frank on the side for his pleurisy & the steward on the neck for the sore throat”

“Cupped the steward on the back of his neck with wine glasses and lanced with razor for want of proper instruments, which gave him almost instant relief”

“Pulled a large jaw tooth for one of the crew. I lanced the gum with a penknife & set him spouting thick blood, & at the second wrench of the iron turned it up.” [Very cheeky language he’s using here, the same sort of talk one uses when hunting whales]

“The loose whale struck Mr. Dean on the lower jaw & broke it, & knocked out 2 of his lower teeth, & he was taken on board [...] Sat up with Mr. Dean last night [...] Bled Mr. Dean [...] Drew 3 teeth from Mr. Deans broken jaw.”

“Bled Antone. Since the death of Manuel, Antone has been on the sick list with swelled testicles and pain in his back. Poor fellow, he is very much frightened & thinks he is going to follow Manuel. He occupies the same bunk. When I bled him, he was so frightened that the perspiration stood on him in large drops, & groaned like a person dying.”

“Blistered and glystered [clystered, i.e. gave an enema] Antone.”

One of John Martin’s watercolors from his journal. NBWM.

Blistering, bleeding, and emetics were among the most common treatments for all that ailed a man aboard. John King included his recipe for creating a blistering plaster and its uses:

“Blisters are serviceable in affections of the chest attended with much pain and difficulty of breathing. Bleeding or purging is proper previous to the application. Severe and long-continued headaches are relieved by a blister to the back of the neck. In all cases before applying a blister, the part should be washed with warm vinegar and wiped dry. The plaster should be spread as thick as a wafer on soft leather. When laid aside it soon becomes mouldy in the dampness of a ship, but if rubbed over with a knife the same one will draw two or three times. When very old it loses its strength. From eight to twelve hours is the time usually required for drawing a blister. Then remove it and dress with basilicon or simple ointment”

—

Other ailments were met with more specific treatments. It was not uncommon to see logbooks noting several men laid low on account of ‘the venereal’.

William Chappell, a cooper and boatsteerer aboard the Saratoga in the early 1850s commented on the frequency the mate found himself off duty following liberty ashore.

“Our mate is off duty again with that disgracefull disease and as near as I can find out it threatens destruction to a small but very usefull member of the body I am sorry for him but he is old enough to know better than to play with every body that looks pretty and bewitching”

“Flaxseed tea is very serviceable in clap”, wrote John King in his journal, as well as white vitriol “sometimes used as an injection in protracted cases of clap.” For syphilis, the common treatments were more severe. King writes,

“No 25. Mercurial Ointment

This is frequently used in venereal cases for bringing the system under the influence of mercury. The bulk of a small nutmeg is rubbed on the inside of the thighs morning and evening until the gums are slightly sore. It is a good application to chancres when mixed with twice the quantity of lard, and renewed twice a day.”

Mercury compounds could also be injected into the urethra. There were doctors who spoke out about the use of mercury in treating syphilis contemporary to when use was at its height. One 1853 advertisement in the New Bedford newspaper the Whaleman’s Shipping List reads,

“Important to the Afflicted

CONFIDENTIAL TREATMENT in Medicine and Surgery may be had of Dr. TOMPKINS at his office in rear of the Apothecary’s Shop, No 58 Middle, corner of North Second St Dr. TOMPKINS gives particular attention to the treatment and cure of private diseases. All those who have been taking medicines of their own prescribing, or from certain inexperienced or self-styled physicians, for a long time without benefit, are respectfully invited to call on Dr Tompkins, who is a regularly educated Physician of twenty years experience, and is competent to treat diseases of all kinds, and in every stage and form.

Dr. T. warns the public against the abuse of mercurials; he is convinced by long experience, that most of the chronic affections, generally supposed to be the relics of diseases, are merely the effects of a long continued course of mercury.

Recent affections cured in a very short time, without a grain of mercury”

Even with such objections, mercury compounds still were the standard and did more to sicken their patients than cure them. While whalers were often listed as being off duty due to venereal disease, there was less comment about whether or not they were given anything to attempt to alleviate it compared to other conditions.

“Our mate limping about again—had another furious attact of the venereal He is a used up man I fear,” Mr. Chappell wrote. Ultimately the mate was in a poor enough condition that he left the voyage at the next provision stop they made.

—

Scurvy was another common affliction. Given that whaleships spent extended time at sea and were loathe to waste too much time with anchoring somewhere, fresh food ran low quite often. When whaling in the Atlantic and South Pacific whalers usually fared okay, as there were a fair number of provision stops in locations that had fresh fruits and vegetables readily available for trade. It was on said provision stops that whalers could also, as said by Samuel Wood of the Bowditch, 1849, take a walk to 'knock the scurvey from their bones’.

In seasons that took place up north however, in the North Pacific, Sea of Okhotsk (Kamchatka Sea), Bering Strait, and eventually up into the Arctic, scurvy was extremely prevalent. The fresh food depleted, the ice was always a threat, and unlike other regions there weren't many accessible places to resupply with large amounts of foods that could ward off scurvy. It's in reading journals during these periods that I find the most complaints of scurvy. And sometimes, the more successful the voyage was, the sicker the men would get because they'd spend more time up there rather than giving up and returning south.

The US Consul in Hawaii complained of this in the 1840s, saying:

"Whaleships were much more successful in taking oil on the North West during the last summer and fall than for three or four seasons previous and most of the vessels remained on the fishing grounds much longer than usual, the consequence of which was that many of the crews were severely afflicted with scurvy, some died after reaching port and before they could be landed, while others were carried to the hospital on litters, being too feeble to walk."

There were endless attempts to ward it off. John Martin wrote of men "In the evening, dancing cotillions and jumping the rope to keep off the scurvey". It didn't seem to do much. Within two weeks:

"One man on the sick list, supposed to be caused by his being so long at sea. All hands are complaining of soreness throughout their bodies. If we do not get on shore soon, we may expect to have half the crew down with the scurvey at least. We have no vegetables on board, and are going into King Georges Sound, New Holland [southwest tip of Australia], a place where we can scarcely get anything to recruit with."

His captain allowed the crew unlimited vinegar and free access to the potato pen. The vinegar, a mistaken remedy due to its acidity, wouldn't have helped much. Potatoes are an excellent source of vitamin C, more so when they're raw, but they were rather intolerable to eat in such a way.

William Chappell spoke of a similar struggle with potatoes, and the grim humor the lads maintained to choke them down:

“Three of our men are off duty with the scurvy which makes its appearance in the knees and feet All hands are called aft every morning to get 2 or 3 potatoes apies which they are required to eat raw in the preasance of the officers for fear they may throw them overboard as many require presing invitation to partake of the dainties They have however a considerable sport over them Call them Kodiak Peaches”\

Aside from the crunch of Kodiak Peaches, Dr. King had his own remedy for scurvy as well:

“13. Salts of Lemon

This is good in scurvy when fresh fruit and vegetables can not be obtained. A teaspoonful dissolved in half a pint of water will form an acid nearly the strength of lime juice. It may be mixed with water and taken freely, sweetened or not. [it makes a good substitute for lemonade, in fever, to allay thirst in fever] Water made slightly acidic with it is a good substitute for lemonade to allay thirst in fever."

The Sailor’s Hospital in Lahaina, Maui, constructed in the early 1830s.

For all the varying attempts to hold off sickness, it took root among crews nearly every voyage. J.E. Haviland of the Baltic, in the early 1850s spent the last few dozen pages of his journal in a state of declining health and low spirits.

“My side and breast pain me nearly all times I have not been on deck since I came below. The Captain and Mr Stivers are both very kind and come down to see me as often as once a day and sometimes two or 3 times. I am taking medicine but it does not seem to do much good but I think I am better than I was at first. Dear mother how I do wish I could see you once more. I get so homesick and I know I am peevish and cross. Some days I cannot get out of my bunk at all. I blame the captain (wrongfully I know) thinking he does not give me the right medicine but it is a very bad place to be sick at sea.”

He suspected it was due to the harsh conditions of whaling up North, but also held a fear within him that it might be something more serious that couldn’t be remedied simply by warmer climes.

“Dear mother, I shall be obliged to leave the ship when we arive at the Sanwich Islands for I do not think I could live doing another season in the cold Norwest. My cough seems to increase and the pain in my side gets no better I am getting weaker each day and am getting very thin in flesh. I have said nothing as yet to the old man about my leaving at the island as I do not know as he will be willing that I should; but I intend going to a doctor and in all probability will tell the old man I am not fit to go North in the ship […] I would like very much to be in the states now for I am afraid this will turn out to be the Consumption that I have. I think if I could have good medical advice I might get rid of it before it got seated upon my lungs. I am afraid it will be a long before I shall see my native land again.”

Ultimately Haviland is discharged from the ship because of his sickness and is left at the Sailor’s Hospital in Lahaina. His stay seems to do him well. His last entry reads:

“I have been here now going on two months and am entirely free from my cough and think I feel as well as ever again. It is intensely hot and I am heartily sick of the place and sincerely wish I could get away but I do not expect any chance before next fall.”

Unfortunately from here he completely drops off the record, so it’s unknown if he ever made it back home. Like so many of these men, he slips through the cracks of documented history. It’s only through their journals, preserved by chance, that their voices and challenges and feelings are known. Often a whaling voyage marked at least one death due to disease or injury. But many also recovered, sometimes rather miraculously given the circumstances and extent of their ailments. In the face of the conditions of a whaler and the limitations of care both in terms of resources and medical understandings at the time, I’m always surprised that there wasn’t more death. People did what they could, with the knowledge they had.

But as so many people expressed while laid up in their bunks: it’s a hard time to be sick at sea.

#some of these things are repurposed from other asks#im still so surprised more people didn't die...#awhalin#haviland makes me sooo sad...and I didn't even include the bits that made me saddest...

148 notes

·

View notes

Text

William Chappell mentioned ‘scrimshonting’ on his voyage but I didn’t know an attributed work of his survives in the New Bedford Whaling Museum’s collections! Here’s a lazy-susan-esque object designed to hold daguerreotype that he made on this 1850s voyage I’m currently going through…

163 notes

·

View notes

Text

How can some people dehumanize folks from the past (based on whatever particular notion that person assumes about ‘the past’) when these 1850s whaling journals are here talking about a bunch of late-teens-early-20s lads farting on each other and running around the ship spanking each other for funsies. People are The Same.

1K notes

·

View notes

Note

I've seen you answer a few asks about whaling history before, so hopefully I'm not offbase asking you questions out of the blue? But anyway, how did people bathe (or keep clean if not by bathing) during long sea voyages?

Not off base at all! Out of the blue whaling history questions are some of my fav asks to receive; I find them thrilling. I can’t help but write an essay every time.

It was particularly hard to keep clean on a whaler, and whalemen were often disparaged by those in other maritime professions. In 1839, naval Lieutenant Charles Wilkes said of the crew of the whaleship America,

“I have seldom seen at sea a more uncombed and dirty set of mariners than his crew.“

J.E. Haviland of the Baltic, 1856, complained of besmirching his journal pages with the grime that he was unable to scrub off his hands after tarring the rigging, self consciously saying:

“My hands + clothes would look beautiful for a ladies Parlor. I see they even collor the paper but I cannot get the tar out. The Old Man says he intends to have me tar down the rigging a few days before we get in New Bedford so that I shall not forget too soon that I have been a sailor.”

General ships’ work such as tarring could be messy, but a whaler’s work was even messier. When trying out blubber it was futile to attempt maintaining any semblance of cleanliness during the process. William Abbe of the Atkins Adams, 1859, said that during boiling, a watch would turn in to their bunks a few hours rest, merely ‘after wiping off your bare body with oakum to take off the thickest of the oil”.

But the gore and oil wasn’t forever. After the particular job was done the ship would be meticulously cleaned, and the whalers would tend to themselves too. As Herman Melville wrote,

“The crew themselves proceed to their own ablutions; shift themselves from top to toe; and finally issue to the immaculate deck, fresh and all aglow, as bridegrooms new-leaped from out the daintiest Holland. Now, with elated step, they pace the planks in twos and threes, and humorously discourse of parlors, sofas, carpets, and fine cambrics; propose to mat the deck; think of having hanging to the top; object not to taking tea by moonlight on the piazza of the forecastle. To hint to such musked mariners of oil, and bone, and blubber, were little short of audacity. They know not the thing you distantly allude to. Away, and bring us napkins!”

Haviland expressed gratitude in getting a chance to get clean after all the work of boiling blubber was done:

“I feel much better to day I have given myself a good wash + a clean shave + got in all clean clothes. You would not have known your own son if you could have seen him yesterday. I was nearly black with smoke + dirt. (with shame) I say it was the accumulation of 2 months dirt + 4 months beard. Everything looks as clean + bright as it did before we took the whale”

Being able to bathe was such a highlight that Abbe titled one of his journal pages “Washing myself!!” With TWO exclamation points!

“I write with pride in my fastidious journal that this morning I washed my face + hands with castile soap + fresh water — when shall I do the like again? When shall I write the pleasant and comfortable fact that I have shaved? The future and fair weather only can tell.”

The ship’s slop chest—its general store—had toiletries for sale, often at a very high premium. Whaling account books show men buying pounds of oil soap for their own personal stores. The fresh water was often rainwater collected for this purpose, rather than the casks set aside for drinking.

“This has been a rather squally day,” wrote Mary Lawrence, whaling wife who accompanied her husband on his ship Addison in the 1850s. “Considerable rain has fallen, and everybody on deck is using an abundant supply of rainwater for washing purposes.” She also added, though this is speaking of laundry rather than bathing, “Having stopped up the scuppers, the use the whole deck for one grand washtub.”

They’d use the sea, too. John Martin of the Lucy Ann, wrote of bathing via rain and sea whilst near the equator on January 24th, 1842.

“Towards noon the rain came down in torrents. The weather being sultry the watch on deck shipped off their shirts to it. John the boat steerer went entirely naked with the exception of a handkerchief tied around his privates. In the afternoon it cleared away, when I asked permission from the Captain for the crew to take a bathe over the side. He said we might do it if we rigged a studding sail over the side, which was soon done & all hands that could swim were to be seen jumping from different parts of the ship. Some went out to the end of the flying jib boom & jumped off there. Even the dog was thrown overboard & got his share of washing. I like bathing at sea but for one thing, and that is sharks. I always have a fear that one might be hovering about and give one a nip before he was aware of it.”

It was challenging for whalers to keep clean by nature of the job, but man when they were able to they really seemed to revel in it. For many of them it was more than just a bath; it was a symbolic return to a home they were long away from, or to the man they perceived themselves to be back on shore, or of a society that they felt cut off from in their line of work.

If you’re interested I also wrote a thing about doing laundry on whaleships too, yonder!

149 notes

·

View notes