#and then there's beliefs and superstitions so far in contradiction with every known fact....not the same even remotely.

Text

it is however true a lot of people, all of them terminally scientifically illiterate, have made 'i fucking love science!' an ideological dogma while not understanding anything about what they're parroting

i have graduate education in immunology but i still know if i said on facebook it was predictable mRNA vaccines would be poorly immunogenic and provide low and transient protection.... i'd get called antiscience for it. even though it's not really a secret in the vaccinology scientific community that the most strongly immunogenic vaccines are live attenuated pathogen in design, and not protein subunit (which is essentially what the mRNA is a template for). it's uncontroversial, even. but saying it on mainstream social media is begging to be burned at the altar. the reasons you can't say this publicly aren't because science dont real and you just dont get magic. it's because there is a lot of money to be made in a comparatively cheap to produce vaccine that you can lobby for legislators to make mandatory for normal participation in society.

i understand some people have some psychological need to believe in things that can't be explained by science to spice up their life or something. given that such beliefs are largely unfalsifiable or tautological, the onus should be on them to admit that if it 'defies natural law' so badly, there's a strong chance it simply doesn't exist

#there's scientific questions at the edge of current knowledge like quantum anything.#and then there's beliefs and superstitions so far in contradiction with every known fact....not the same even remotely.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Medieval Magic Week: Witchcraft in Early Medieval Europe

Apologies for not getting to this last week, but I will try to be at least semi-reliable about posting these. If you missed it: I’m teaching a class on magic and the supernatural in the Middle Ages this semester, and since the Tumblr people also wanted to be learned, I am here attempting to learn them by giving a sort of virtual seminar.

Last week was the introduction, where we covered overall concepts like the difference between magic, religion, and science (is there one?), who did magic benefit (depends on who you ask), was magic a good or a bad thing in the medieval world (once again, It’s All Relative) and who was practicing it. We also brought in ideas like the gendering of supernatural power (is magic a feminine or a masculine practice, and does this play into larger gendered concepts in society?) and did some basic myth-busting about the medieval era. No, not everybody was super religious and mind-controlled by the church. No, they were not all poor farmers. No, not every woman was Silent, Raped, and Repressed. Magic was a common and folkloric practice on some level, but it was also the concern of educated and literate ‘worldly’ observers. We can’t write magic off as the medieval era simply ‘not knowing any better,’ or having no more sophisticated epistemology than rudimentary superstition. These people navigated thousands of miles without any kind of modern technology, built amazing cathedrals requiring hugely complex mathematical and engineering skill, wrote and translated books, treatises, and texts, and engaged with many different fields of knowledge and areas of interest. They subjected their miracle stories to critical vetting and were concerned with proving the evidentiary truth of their claims. We cannot dismiss magic as them having no alternative explanation or way of thinking about the world, or being sheltered naïve rustics.

This week, we looked at some primary sources discussing ‘witchcraft’ beliefs in early medieval Europe, which for our purposes is about 500—eh we’ll say 1000 C.E. We also thought about some questions to pose to these texts. Where did belief in witchcraft – best known for early modern witch hunts – come from? How did it survive through centuries of cultural Christianisation? Why was it viewed as useful or as threatening? Scholars have tended to argue for a generic mystical ‘shamanism’ in pre-Christian Europe, which isn’t very helpful (basically, it means ‘we don’t have enough evidence, so fuck if we know!’). They have also assumed that these were ‘superstitions’ or ‘relics’ of pagan belief in an otherwise Christian culture, which is likewise not helpful. We don’t have time to get into the whole debate, but yes, you can imagine the kind of narratives and assumptions that Western historiography has produced around this.

At this point, Europe was slowly, but by no means monolithically, becoming Christian, which meant a vast remaking of traditional culture. There was never a point where beliefs and practices stopped point-blank being pagan and became Christian instead; they were always hybrid, and they were always subject to discussion and debate. Obviously, people don’t stop doing things they have done a particular way for centuries overnight. (Once again, this is where we remind people that the medieval church was not the Borg and had absolutely no power to automatically assimilate anyone.) Our first text, the ‘Corrector sive medicus,’ which is the nineteenth chapter of Burchard of Worms’ Decretum, demonstrates this. The Decretum is a collection of ecclesiastical law, dating from early eleventh-century Germany. This is well after Germany was officially ‘Christianised,’ and after the foundation of the Holy Roman Empire as an explicitly Christian polity (usually dated from Charlemagne’s coronation on 25 December 800; this was the major organising political unit for medieval Germany and the Carolingians were intensely obsessed with divine approval). And yet! Burchard is still extremely concerned with the prevalence of ‘magical’ or ‘pagan’ beliefs in his diocese, which means people were still doing them.

The Corrector is a handbook setting out the proper length of penances to do (by fasting on bread and water) for a variety of transgressions. It can seem ridiculously nitpicky and overbearing in its determination to prescribe lengthy penances for magical offenses, which are mixed in among punishments for real crimes: robbery, theft, arson, adultery, etc. This might seem to lend legitimacy to the ‘killjoy medieval church oppressing the people’ narrative, except the punishments for sexual sins are actually much lighter than in earlier Celtic law codes. If you ‘shame a woman’ with your thoughts, it’s five days of penance if you’re married, two if you aren’t, but if you consult an oracle or take part in element worship or use charms or incantations, it could be up to two years.

Overall, the Corrector gives us the impression that eleventh-century German society was a lot more worried about whether you were secretly cursing your neighbour with pagan sorcery, rather than who you’re bonking, even though sexual morality is obviously still a concern, and this reflected the effort of trying to explicitly and completely Christianise a society that remained deeply attached to its traditional beliefs and practices. (There’s also a section about women going out at night and running naked with ‘Diana, Goddess of the Pagans’, which sounds awesome sign me up.) Thus there is here, as there will certainly be later, a gendered element to magic. Women could be witches, enchantresses, sorceresses, or other possible threats, and have to be closely watched. Nonetheless, there’s no organised societal persecution of them. Formal witch hunts and witch trials are decidedly a post-Renaissance phenomenon (cue rant about how terrible the Renaissance was for women). So as much as we stereotype the medieval world as supposedly being intolerant and repressive of women, witch hunts weren’t yet a thing, and many educated women, such as Trota of Salerno, had professional careers in medicine.

The solution to this problem of magical misuse is not to stop or destroy magic, since everyone believes in it, but to change who is legitimately allowed to access it. Valerie Flint’s article, ‘The Early Medieval Medicus, the Saint – and the Enchanter’ discusses the renegotiation of this ability. Essentially, there were three categories of ‘healer’ figure in the early Middle Ages: 1) the saint, whose miraculous power was explicitly Christian; 2) the ‘medicus’ or doctor, who used herbal or medical treatment, and 3) the ‘enchanter’, who used pagan magical power. According to the ecclesiastical authors, the saint is obviously the best option, and believing in/appealing to this figure will give you cures beyond the medicus’ ability, as a reward for your faith. The medicus tries his best and has good intentions, but is limited in his effectiveness and serves in some way as the saint’s ‘fall guy’. Or: Anything the Doctor Can (Or Can’t) Do, The Saint Can Do Better. But the doctor has enough social authority and respected knowledge to make it a significant victory when the saint’s power supersedes him.

On the other hand, the ‘enchanter’ is basically all bad. He (or often, she) makes the same claim to supernatural power as the saint, but the power is misused at best and actively malicious and uncontrollably destructive at worst. You are likely to be far worse off after having consulted the enchanter than if you did nothing at all. Both the saint and the enchanter are purveyors of ‘magical’ power, but only the saint has any legitimate claim (again, according to our church authors, whose views are different from those of the people) to using it. The saint’s power comes from God and Jesus Christ, the privileged or ‘true’ source of supernatural ability, while the enchanter is drawing on destructive and incorrect pagan beliefs and making the situation worse. The medicus is a benign and well-intentioned, if not always effective, option for healing, but the enchanter is No Good Very Bad Terrible.

The fact that ecclesiastical authors have to go so hard against magic, however, is proof of the long-running popularity of its practitioners. The general public is apparently still too prone to consult an enchanter rather than turn to the church to solve their problems. The church doesn’t want to eradicate these practices entirely, but insists that people call upon God/Christ as the authority in doing them, rather than whatever local or folkloric belief has been the case until now. It’s not destroying magic, but repurposing and redefining it. What has previously been the unholy domain of the pagan is now proof of the ultimate authority of Christianity. If you’re doing it right, it’s no longer pagan sorcery, but religious miracles or devotion.

Overall: what role does witchcraft play in early medieval Europe? The answer, of course, is ‘it’s complicated.’ We’re talking about a dynamic, large-scale transformation and hybridising of culture and society, as Christian religion and society became more prevalent over long-rooted pagan or traditional beliefs. However, these beliefs arguably never fully vanished, and were remade, renamed, and allowed to stay, without any apparent sense of contradiction on the part of the people practicing them. Ecclesiastical authorities were extremely concerned to identify and remove these ‘pagan’ elements, of course, but the general public’s relationship with them was always more nuanced. When dealing with medieval texts about magic, we have a tendency to prioritise those that deal with a definably historical person, event, or place, whereas clearly mythological stories referring to supernatural creatures or encounters are viewed as ‘less important’ or as the realm of historical fiction or legend. This is a mistake, since these texts are still encoding and transmitting important cultural referents, depictions of the role of magic in society, and the way in which medieval people saw it as a helpful or hurtful force. We have to work with the sources we have, of course, but we also have to be especially aware of our critical assumptions and prejudices in doing so.

It should be noted that medieval authors were very concerned with proving the veracity of their miracle narratives; they did not expect their audiences to believe them just because they said so. This is displayed for example in the work of two famous early medieval historians, Gregory of Tours (c.538—594) and the Venerable Bede (672/3—735). Both Gregory’s History of the Franks and Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People contain a high proportion of miracle stories, and both of them are at pains to explain to the reader why they have found these narratives reliable: they knew the individual in question personally, or they heard the story from a sober man of good character, or several trusted witnesses attested to it, or so forth. Trying to recover the actual historicity of reported ‘miracle’ healings is close to impossible, and we should resist the cynical modern impulse to say that none of them happened and Gregory and Bede are just exaggerating for religious effect. We’re talking about some kind of experienced or believed-in phenomena, of whatever type, and obviously in a pre-modern society, your options for healthcare are fairly limited. It might be worth appealing to your local saint to do you a solid. So to just dismiss this experience from our modern perspective, with who knows how much evidence lost, in an entirely different cultural context, is not helpful either. There’s a lot of sneering ‘look at these unenlightened religious zealots’ under-and-overtones in popular conceptions of the medieval era, and smugly feeling ourselves intellectually superior to them isn’t going to get us very far.

Next week: Ideas about the afterlife, heaven, hell, the development of purgatory, the kind of creatures that lived in these realms, and their representation in art, culture, and literature.

Further Reading:

Alver, B.G., and T. Selberg, ‘Folk Medicine As Part of a Larger Complex Concept,’ Arv, 43 (1987), 21–44.

Barry, J., and O. Davies, eds., Witchcraft Historiography (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2007)

Collins, D., ‘Magic in the Middle Ages: History and Historiography’, History Compass, 9 (2011), 410–22.

Flint, V.I.J, ‘A Magical Universe,’ in A Social History of England, 1200-1500, ed. by R. Horrox and W. Mark Ormrod (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 340–55.

Hall, A., ‘The Contemporary Evidence for Early Medieval Witchcraft Beliefs’, RMN Newsletter, 3 (2011), 6-11.

Jolly, K.L., Popular Religion in Late Saxon England: Elf Charms in Context (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996)

Kieckhefer, R., Magic in the Middle Ages (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000)

Maxwell-Stuart, P.G., The Occult in Mediaeval Europe (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2005)

Storms, G., Anglo-Saxon Magic (The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1947)

Tangherlini, T., ‘From Trolls to Turks: Continuity and Change in Danish Legend Tradition’, Scandinavian Studies, 67 (1995), 32–62.

45 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Titania

TRUE NAME: Yes

FACECLAIM: Lana Parrilla

NICKNAMES AND ALIASES: A queen garners many names, especially given how long Titania has been in power. In the mortal realm, she's been going by Titania Verano

DATE OF BIRTH: Unknown

APPARENT AGE: 39

ACTUAL AGE: Unknown

GENDER: Identifies as female

KIND: High Fae

CALLING: Summer Queen, sole ruler of the Summer Court. Musical producer and CEO at Midsummer Records.

DISTINGUISHING MARKS: Titania has a scar through her upper lip from the attack that had ended in Oberon's death. She chose not to have it heal, as a mark of respect. It becomes all the more evident in her high fae form. In her high form, she's almost too bright to look at, like staring at the sun. When you blink, all you can see is her light in your eyelids. She's bright and she burns. To be close to her for longer than an instant would be to embrace the fact that you'll turn to ash or to burn hot in return.

Somehow, she always smells of the headiness of a lavender field and scarlet sage, sweet and heavy in turns. Relaxing, soothing in the strangest sort of ways.

To have her favor is to remember the sweet nights of summer, the headiness of flowers blooming and the cool that might finally come as respite. Iced tea and evenings together with family, with people you love, while cicadas provide their music. To face her wrath, though, is to be in the desert in the peak of summer. All you can hope for is that the mirage of water might even be real. Maybe it would be, this time. If you can ever reach it. If not, well - things grow, from ashes. Perhaps she'll remake you into something wonderful.

Beyond that, she is of the fair folk - her shape changes as easily as breathing, were she so inclined. The most distinguishing marks are the quickness of her temper. Every time her temper flares, the heat in the room seems to jump several degrees, while her hands seem to twitch as though wishing for flames.

PERSONALITY: Titania of reality is not far off from the popular adaptations of her - though if she started that way or if the belief of humans shaped her into it isn't exactly clear. She's the epitome of summer, incredibly passionate and led by them. She falls in and out of love easily, is vengeful and temperamental but cools off given a bit of time.

Most of all, however, she's determined. One cannot become a monarch of the Summer Court without a strong will and the strength to beat out all the rest - and Titania has consistently won with her magic for centuries now. When she puts her mind to something, she will achieve it come hell or high water. And she's willing to do absolutely anything necessary to keep her court safe. She's proud and stubborn, willing to set her feet and hold firm on whatever she has decided on.

HISTORY:

It does not matter to whom a queen was born to - they have long since passed into slumber, barely named in the human mythos, long since forgotten in the intervening centuries upon centuries. Far as mortals need be concerned, Titania might as well have sprung forth fully grown and in her full glory. And it's not as though there are any fae who remain awake to contradict the image - any who might have remembered her as one of the rare children the fae could celebrate are long since gone. What matters is that she was born a daughter of the Summer Court and was formed from that, formed into it. Titania reflects her Court, passionate and volatile and untamed. Oberon had been her ally for a long time, the two balancing their strengths well enough to be a real threat - him with the martial combat, her his magical counterpart. The two challenged the sitting monarch for the throne and won, becoming the reigning monarchs for cycle upon cycle. Other fae challenged and lost, as was the nature of summer, but their strength was remarkable - they lived and reigned and worked.

But Summer was long since known for being a court that involved itself with the mortal realm, and they were no different. Both took on mortal lovers, mortal friends, mortal younglings to raise and pet and praise and love. Quarreled over them regularly - Shakespeare got that much right, at least. But long before Titania had sent her fairies to whisper in his ear, the Summer Court had done the unthinkable - they attempted to integrate themselves into a mortal court. They sent one of their changelings, the lady Morgaine le Fay, to the court of King Arthur and presented the opportunity for their courts to rule more jointly. More so than had ever been offered to a mortal before, Titania and Oberon taking the opportunity to reveal themselves to mortals and take advantage of all that could be offered. There was safety in the mortals knowing of them, after all - take advantage of their wariness, their knowledge in the power that the fairies held. And for a time, it worked.

But magic and faeries and mysticism was not something that kept sway in humans forever. They were flighty creatures, starting to turn their attention instead to religion, to a jealous god who denied all other powers but him. And with awareness of power came an awareness of weakness.

The mortals turned on them as Arthur weakened, turned his attention to the rebellion of his own bastard son. Morgaine fell as Summer's mound was invaded, iron burning fairy flesh as their screams filled the air with a different sort of music. Oberon fell, Titania took grievous wounds, and their link in Morgaine burned. A fallen goddess' rage ended up as a large point in their favor, allowing for the fairies to rally around the new power and the rage of their Queen, who burned bright as the sun. Burned the eyes of mortals foolish enough to even look in her direction. Those that did were struck down with no warning, no mercy. Titania struck down the remaining attackers, bringing her court back to momentary peace and abandoning Arthur to the bed of his own making. She awarded the goddess with the title of "le Fay" in memory of the changeling she saw as her daughter and for her defense of Summer, then took her court and retreated to a new mound.

Titania took control of her court for herself alone - there were many challengers, after the disaster of Arthur's court. She defeated every single one, determined in her grief. And for a time, they settled into the Tamar Valley and knew some peace. They slowly began to reach back out to mortals again, inspiring writers and whispering tales into their ears to be recorded in plays and poetry and novels. But mortals slowly turned again, losing faith and reverence in the fairies. Of course some superstition remained. Their rings were avoided, signs left were treated with the proper fear. But the mining began.

Her court again began to suffer, centuries passing as they became more and more poisoned with the nearby iron. The pollution. Their areas of play were reduced for fear of the mortals, of the increasingly terrifying machines they built. The court withered, became more chaotic as the threats they faced became seemingly insurmountable. And Titania proposed a new plan - to try again, in the mortal world. To try and connect themselves to it, so that they might flourish instead of being choked off.

The challenges began again - it took decades, the court debating amongst itself while the eldest of the court slowly kept slipping off into deeper places in the Earth to sleep instead of bothering. Given time, Titania finally managed to convince them. And so the Summer Court again moved. This time, to Nashville. They began to plan, to create, to inspire again as Titania and others started to build. A mound for the modern world. While many fairies had stayed behind, unwilling to leave their previous mound and its protections, or the sleeping lying deep in its depths, other wild fae slowly crept forward in curiosity. They begged Titania for an audience, for a chance.

She granted it. The Summer Court would adapt, she vowed. And it would grow.

FAMILY:

Oberon (husband, deceased) - Theirs was a marriage of convenience, but they did love each other in their way. Once, twice, many times. Almost as many times as they hated each other, swore that this would be the last time he would be allowed into her bed. They fought and schemed and tricked and lusted and loved endlessly, the cycle almost as dependable as the cycle of the seasons themselves. For as turbulent as their relationship was, however, the respect they had for each other was deeply embedded within them. They complimented each other's strengths well, especially when united against an outside threat or united in their willingness to be merciful. For all their faults, there was always some genuine affection beneath it all. And Oberon's murder struck Titania deeply, to the point where she still grieves the loss of her partner. She took both the trials of magic and might herself every cycle since Oberon has passed, taking complete control of the court herself in her unwillingness to partner with any other. Her king has passed. Long live the queen, in all her glory.

SEXUALITY AND RELATIONSHIP STATUS: Pansexual, widowed. Titania has no interest in another lover.

OTHER TIES:

Robin Goodfellow (Puck): A near constant source of annoyance for Titania, but a loyal one if nothing else. Robin is one of the strongest courtiers in the Summer Court, even if he is something of a wild card. He was loyal most to Oberon, but does take some direction still from Titania. Even if that direction seems to be mostly shooing him away from her secretary's desk and out of her way. He's dubbed himself Titania's personal pest, but she trusts him far more than she'd ever admit out loud. If nothing else, he's loyal to her and it's far better the devil you know. But that doesn't mean she hasn't forgotten the damned donkey head business.

WANTED CONNECTIONS: Robin Goodfellow (Puck), other members of the Summer Court especially

LIKES: Warmth, a red lipstick that actually lasts more than an hour, good tailoring, jewel tones, iced tea, Indian food and spices, musical talent, peaches, sangria

DISLIKES: Cold, Winter, The Erlking, Puck, the phone ringing, stressed out artists, losing

HOBBIES: Growing peaches, bee keeping, befriending mortals and learning of their lives, watching the stars move in their rotations, amusing herself by reading the latest tripe mortals have produced of her, taking on different forms and faces to travel all over the world, travelling through the suns own rays. She loves going to the very centers of the deserts, in the complete solitude of it, soaking up the heat and the small lives of the few plants and animals brave enough to be there.

SKILLS: Stoking passion and soothing rage in turns. Leading her court and somehow managing all of the fiery tempers, the various passions into something approaching order. Finding talent and stoking it into something glorious and blazing. Burning that which is harmful or useless, building something new and stronger from the ashes

MEDICAL CONDITIONS: None

CURRENT FINANCIAL STATUS: What she and the court make go into a collective, essentially. They all have more than what they really know what to do with, at this point.

PLACES: The Summer Court’s Mound, concealed within the Midsummer Records building on Music Row.

PETS: Titania tends to several bee hives, but one in particular seems very attached to her. Their queen has been known to drift out and confer with her frequently - for bees know just about everything, you know. They hear many things. Titania calls their queen Esme for a mortal series that caught her attention.

She often has a cat loping along after her, a little domestic serval that can't bear to have his owner far from his sight - Cobweb, simply because she was so tickled by Shakespeare's play. For those paying enough attention, however, or with just a little magic... there's something just a bit off, about the cat. Sometimes its shadow seems too large, for such a cat. Its pawsteps too heavy for something so small. And for those with the sight, well, sometimes he seems far more like a lion.

KNOWN MAGIC: Titania is extremely strong in her magics, both destruction and that of growing. In truth, however, she is strongest at destroying - fire being her preference. She draws strongest on elemental magics, but she is offensively trained far more than defensively.

MAGICAL ITEMS: A crown woven of gold frame with an ever changing arrangement of flowers woven into it- one day it might be marigolds and zinnias, the next it might be peonies and plumeria. Other times, it is flame itself woven into the crown, while the flowers are nothing more than ashes ever burning.

An onyx sword, long ago shaped and forged for the monarch of the Summer Court.

RUMORS: Some whisper she's gone mad, after the death of Oberon. It must be madness, to have taken her court into the mortal world, to create a mound inside the city itself. Madness or, perhaps, ambitious - Oberon's death and the attack on them is surrounded by hushed whispers and mystery. And she's managed to take the throne for herself entirely since then, perhaps ambition finally overtook her fondness for him. Perhaps the iron that entered Oberon's heart was thrust there by his very own wife.

WRITING SAMPLE:

"Do I really want to know?" Titania stared up at the monstrosity currently blocking the lobby, what had once been carved driftwood and plants woven together into something... else. She wasn't exactly certain what it was supposed to be, but there was no doubt that it was a problem. Mostly because driftwood wasn't meant to grow. Especially not within an hour.

"Do you really have to ask?" Amber shot her a sardonic half smile, the leanan sídhe poking halfheartedly at the branches. The closest thing she had to a reliable second-in-command, really, her value was endless in this mortal world - she'd taken mortal lovers for centuries, as a wild fae. She understood their technology far better than Titania herself did - and miles above the more resistant members of the court.

Titania grimaced at the question, nodding to concede the point, "Of course it was him. Did he give a reason, this time?"

"He thought you seemed bored today."

"Not bored enough for this kind of shit," Titania muttered, trying to figure out if she should spend the extra time unweaving the spell or just go fetch a dryad to mess with it. She mostly just wanted to set it all aflame, but that would just attract panic. Even if they weren't outright caught by one of the many recording artists, agents, press, and assorted others in the building today, the smoke smell was difficult to actually get out of a room. She knew that from personal experience.

She sighed, putting her hands against the bark of the driftwood and closing her eyes, starting to whisper a slow, singing sort of spell. The effect wasn't immediate, but it became apparent soon enough as the wood began to creak and moan, reshaping itself with groaning complaints but willing to listen. Hard not to, with such a soft song curling around, whispering and cajoling as though it were sentient itself. The sculpture restructured itself into whatever abstract nonsense it had been before, slowly, as Titania began to fade off.

The burst of applause was met with a sullen glare to the source while he just continued to grin triumphantly. "See? You were bored. And easy fix, right? I know, I know, you can thank me later."

"Puck-" Her menacing tone was cut off blithely as Puck stuck his head around the corner again to interrupt.

"Oh, by the way, there's a messenger waiting in your office for you, someone from the Spring Court?"

Her sigh was even louder the second time around, all the more aggrieved. This wasn't exactly what she had in mind for excitement. But she supposed it worked all the same.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

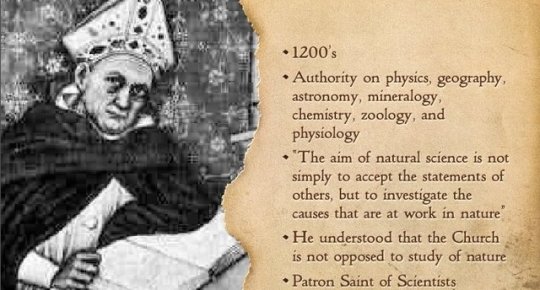

Reflections of a Catholic Scientist - Part 6

Thoughts on belief, knowledge and faith---rational and irrational; my journey to faith, and on the "Limits of a limitless science" (to paraphrase Fr. Stanley Jaki). A discourse on the consonance of what science tells us about the world, and the dogma/teachings of the Catholic Church; you don't have to apologize for being Catholic if you're a scientist.

Where is the Catechism of Science?

"Science can purify religion from error and superstition; religion can purify science from idolatry and false absolutes. Each can draw the other into a wider world, a world in which both can flourish." Pope St. John Paul II, Letter to Rev. George Coyne, S.J., Director of the Vatican Observatory.

"Christianity possesses the source of its justification within itself and does not expect science to constitute its primary apologetic." ibid.

"It can be said, in fact, that research, by exploring the greatest and the smallest, contributes to the glory of God which is reflected in every part of the universe." Pope St. John Paul II, Address on the Jubilee of Scientists, 2000

INTRODUCTION

My latest book (department of shameless self-promotion), "Science versus the Church--'Truth Cannot Contradict Truth,'" is available on Amazon.com and leanpub.com, the latter in a pdf format. I've decided to add a final chapter, a summing up, and I thought the best way would be to compare our Catholic Catechism (in its old familiar form, the Baltimore Catechism), with what a similar catechism might be, formed from the opinions of non-believing scientists.

I won't claim that the answers in the science Catechism are true--indeed, there are contradictory responses--and I don't know of any of the assertions have been empirically validated. In short, the science catechism fails the ultimate test of any scientific project; it is not and cannot be shown to hold by replicable measurements.

THE BALTIMORE CATECHISM:

1. Who made us?

God made us.

"In the beginning, God created heaven and earth." Genesis 1:1

2. Who is God?

God is the Supreme Being, infinitely perfect, who made all things and keeps them in existence.

"In him we live and move and have our being." Acts 17:28

3. Why did God make us?

God made us to show forth His goodness and to share with us His everlasting happiness in heaven.

"Eye has not seen nor ear heard, nor has it entered into the heart of man, what things God has prepared for those who love him." I Corinthians 2:9

4. What must we do to gain the happiness of heaven?

To gain the happiness of heaven we must know, love, and serve God in this world.

Lay not up to yourselves treasures on earth; where the rust and moth consume and where thieves break through and steal. But lay up to yourselves treasures in heaven; where neither the rust nor moth doth consume, and where thieves do not break through nor steal. Matthew 6:19-20

THE CATECHISM ACCORDING TO SCIENCE:

1. Who made us?

Life came about by chance and we evolved from that first life.

“An honest man, armed with all the knowledge available to us now, could only state that in some sense, the origin of life appears at the moment to be almost a miracle, so many are the conditions which would have had to have been satisfied to get it going.” Francis Crick, Life Itself: Its Origin and Its Nature

2. What is the entity that made the universe from which this life came?

There are several answers:

"Evolutionary cosmology formulates theories in which a universe is capable of giving rise to and generating future universes out of itself, within black holes or whatever." Robert Nozick

"As scientists, we track down all promising leads, and there's reason to suspect that our universe may be one of many - a single bubble in a huge bubble bath of other universes. Brian Greene

" Thus, CCC [Cyclic Conformal Cosmology] proposes that what current cosmology refers to as “the entire history of the universe” (but without any early inflationary phase) is just one aeon of a succession of such aeons, that continues indefinitely in both temporal directions." Roger Penrose.

"Because there is a law such a gravity, the universe can and will create itself from nothing." Stephen Hawking.

3, Why did the entity that made the universe make us?

Why questions, that is questions involving purpose--teleology--are outside the domain of science.

"Teleology is a lady without whom no biologist can live. Yet he is ashamed to show himself with her in public." H.A. Krebs (he of the Krebs Cycle)

"It looks as if the offspring have eyes so that they can see well (bad, teleological, backward causation), but that's an illusion. The offspring have eyes because their parents' eyes did see well (good, ordinary, forward causation)." Steven Pinker

"The universe that we observe has precisely the properties we should expect if there is, at bottom, no design, no purpose, no evil, no good, nothing but pitiless indifference.” Richard Dawkins

'Why' implicitly suggests purpose, and when we try to understand the solar system in scientific terms, we do not generally ascribe purpose to it.” Lawrence Kraus

4. What must we do to get the happiness of heaven?

There is no heaven.

We should not despair, but should humbly rejoice in making the most of these gifts, and celebrate our brief moment in the sun.” Lawrence Kraus

"I regard the brain as a computer which will stop working when its components fail. There is no heaven or afterlife for broken down computers; that is a fairy story for people afraid of the dark." Stephen Hawking

CONCLUSION

I won't bother to analyze each of the answers given for the science catechism. They are discussed in previous chapters of my book, Science versus the Church, (for example, "the brain as a computer", and there is no universal agreement amongst scientists or philosophers. If any of you readers would like to argue for them, I'd be glad to hear your arguments.

Added 20th August, 2016. Several readers of this post have read the above post as my argument that this is what science is all about. That's far from the case. What I am trying to show, possibly ineptly, is by a literary device called "situational irony" that contrary to the claims of the scientists from whom the quotes are drawn, that science does not explain everything there is to be known about our world and life.

In short, I have tried to expose "scientism" for the fraud it is, but my opinion of science as it should be conducted (which was not the topic for this post) is much different. See, for example, my posts: "Peeling back the onion layers: gravitational waves detected", "Tipping the Sacred Cow of Science--Confessions of a Science Agnostic", "God, Symmetry and Beauty in Science: a Personal Perspective." to see what my idea of science is all about.

From a series of articles written by: Bob Kurland - a Catholic Scientist

0 notes