#and then cut to bolsonaro's government and covid and it just

Text

reading up on what's happening to our hermanos in argentina and then how the usa probably had a hand in the coup that ousted dilma here in brazil in 2016 etc

( not to mention palestine and sudan and yemen and )

i feel so tired

why do we have to pay again and again and again so the usa and billionaires can maintain it's power and hegemony

just why

#i just hate it#y'know when i was a child i used to read those little comics the government gave#about fome zero#“zero hunger” program#i remember with time i stopped seeing them because it was mostly successful#so i grew up in this brazil where my family had this idea that things would only get better#i remember that my mom struggled to buy me candies and ice cream#but we had a house with lemon and orange trees and my grandpa had a plot of land where he planted corn and sugar cane#we moved from that house but we didn't struggle for the basics#and then cut to bolsonaro's government and covid and it just#our ability to buy food was adhbgbnhjmfkv#i have never! gone! through food insecurity like this#txt#mari talks

0 notes

Note

As someone who is not well versed in Brazilian politics, may I ask what change do you want to see with the new presidency? Thanks. ☺️

It's less about structural change and more about going back to normality.

The first thing you need to understand is that Brazil just lived four years of literal fascism. A less explicit version of fascism, but fascism still. And so, the bar for the next government is underground low.

All I want is a president who won't pick up people with dwarfism thinking they're children.

Twice.

Someone who won't steal somebody else's dog and then having to return it to its rightful owner.

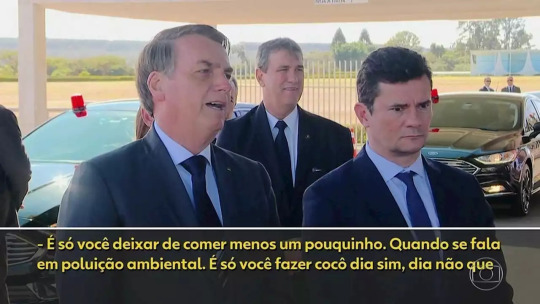

A president whose environmental policies aren't reduced to "only pooping every other day..."

...Or getting beef with Hollywood celebrities.

I want a president who won't have to eat pizza on the streets of New York city because no restaurant would allow a non vaccinated person to go inside.

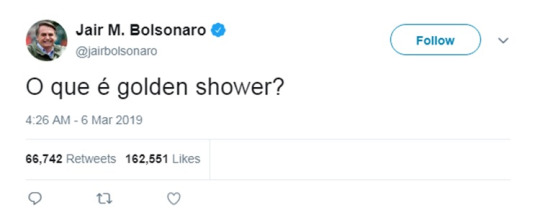

Someone who won't ask what golden shower is. On his official Twitter account.

Or encourage a crowd to chant "imbrochável," a slightly vulgar Portuguese word that translates roughly to "never limp," to himself.

I dream of a president who can eat like a normal human being.

And who won't send a humorist to a press conference just to fuck with the journalists and take focus away from our pathetic economy "growth."

I'd honestly settle for someone who won't gratuitously offend the First Lady of France.

Or who won't wait hours in a hall to say "I love you" to Donald Trump just to get blatantly ignored.

A president who won't salute other countries' flags.

Or neglect international obligations in order to cut his hair.

Most importantly, I want a president who, in the middle of the worst pandemic of recent history, won't offer an ineffective medicine for covid to a fucking emu.

I purposely kept this relatively funny, but the sad truth is that Bolsonaro is military scum. He defends the Military Dictatorship Brazil was under (1964-1985) to this day.

He has openly said he's a torture enthusiast. He has told a woman he wouldn't rape her because she doesn't even deserve that from him. He has said there was "a mood" between him and some 14 years old girls he met. He has lied about indigenous people indulging in cannibalistic practices, stating that he'd eat an indigenous man himself, no problem.

Bolsonaro is a negationist. Of the pandemic, of the vaccines, of the climate changes, of our very history. He called covid "a little flu," mocked people wo died due to the lack of air, neglected buying the vaccines, said he wouldn't be responsible if the ones who took the shot turned into alligators, constantly fought against the use of masks and the implementation of lockdown.

To him, the Military Dictatorship of '64 wasn't a dictatorship at all and it should have killed more people. When he was a congressman, he voted "yes" to impeach president Dilma Rousseff, while paying tribute to the man who tortured her in that very same dictatorship se fought against.

He has made easier for people to get guns. Women, LBGTQIA+, black and indigenous people everywhere didn't feel safe anywhere anymore because police brutality and bigotry escalated to alarming levels. Under the first three years of his administration, Amazon's deforestation rate rose 73%.

And to top it all off, this has been the most corrupt government since our redemocratization, but nothing is investigated because Bolsonaro is actively interfering on everything just to save his and his sons' asses.

After years of him putting our electoral system in check and saying without any proofs that the whole thing is rigged, his supporters are blocking important avenues, protesting against his loss even three days later and calling for a fucking Military Coup.

So yeah. I just want normalcy back.

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wednesday, January 3, 2024

Less sustainable

(NYT) The federal debt starts the new year at a level that is hard to grasp: $34 trillion. That is 1.2 times the U.S.’s annual economic output. Both parties have contributed to the situation. Republicans have passed large tax cuts. Democrats have enacted ambitious climate and health care initiatives. Both funneled money to Americans in response to the Covid pandemic. For years, many economists believed the country’s debt was not a problem. But times have changed, and federal deficits now look scarier. In November, the financial firm Moody’s lowered its outlook on U.S. debt from “stable” to “negative.” The solution remains unclear. And the economy may be able to continue growing at a steady clip for years despite the debt. At some point, though, the federal government will likely need to raise taxes and cut spending in ways that many Americans will find unpleasant.

Biden and Trump are poised for a potential rematch that could shake American politics

(AP) U.S. presidential elections have been rocked in recent years by economic disaster, stunning gaffes, secret video and a pandemic. But for all the tumult that defined those campaigns, the volatility surrounding this year’s presidential contest has few modern parallels. In the coming weeks, the high court is expected to weigh whether states can ban former President Donald Trump from the ballot for his role in leading the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection at the U.S. Capitol. Meanwhile, a federal appeals court is weighing Trump’s argument that he’s immune from prosecution. The maneuvers are unfolding as prosecutors from New York to Washington and Atlanta move forward with 91 indictments across four criminal cases involving everything from Trump’s part in the insurrection to his efforts to overturn the 2020 election and his hush money paid to a porn actress. On the Democratic side, President Joe Biden is seeking reelection as the high inflation that defined much of his first term appears to be easing. But that has done little to assuage restless voters or ease widespread concerns in both parties that, at 81, he’s simply too old for the job.

Maine Secretary of State Targeted by ‘Swatting’ After Trump Ballot Decision

(NYT) Maine’s secretary of state was the victim of a “swatting” call to her home, the authorities said, the latest politician to be targeted in recent weeks by people reporting fake crimes to the police, hoping to provoke heavily armed responses. A hoax call was placed on Friday night, just a day after the secretary of state, Shenna Bellows, barred Donald J. Trump from the state’s ballot, a politically fraught decision that drew criticism from Republicans across the country. The state police said that in the call, a man claimed to have broken into Ms. Bellows’s home in Manchester, just outside the capital city of Augusta. State troopers searched the residence, but did not find anything suspicious. Swatting incidents have risen in recent years, and advances in technology have made it easier for perpetrators to make 911 calls sound more credible. In the days before the hoax call against Ms. Bellows, numerous other high-profile politicians said swatters had targeted their homes.

Brazil’s economy improves during President Lula’s first year back, but a political divide remains

(AP) Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva likes to boast he had a good first year after returning to the job. The economy is improving, Congress passed a long-overdue tax reform bill, rioters who wanted to oust him are now in jail, and his predecessor and foe Jair Bolsonaro is barred from running for office until 2030. Still, the 78-year-old leader has struggled to boost his support among citizens and lawmakers. Some major setbacks, including a series of votes by Congress to override his vetoes, signaled that Lula’s future could be less productive in a Brazil almost evenly split between his supporters and Bolsonaro’s. “Brazil’s political polarization is such that it crystallized the opinions of Lula and Bolsonaro voters beyond the economy,” said political consultant Thomas Traumann, the author of a recent best-selling book on Brazil’s political divisions. “These groups are separated by very different world views, the values that form the identity of each group are more important than food prices or interest rates.”

British fish and chips is endangered

(NBC News) Ever since she was old enough to walk, Terrilea Coglan was climbing aboard fishing boats that set sail each morning from the rocky beachfront of Hastings to harvest the key ingredient in Britain’s most iconic dish: fish and chips. The day’s catch travels just a short way from the boats up to the seaside fish and chips shops, or “chippies,” that pride themselves as much in the freshness of the fish as in the secret recipes for their gooey batter. Now, all along the British coast, towns like Hastings are being squeezed by a cost-of-living crisis that’s hit the supply chain behind fish and chips, pushing up prices beyond what some are willing to pay for a humble, if comforting, weeknight meal. The cost of diesel to power the fishing boats, the sunflower oil to fry the fish and the electricity to run the friers have all skyrocketed. The high prices are threatening a billion-dollar business and a staple of the British menu: Every year, Brits eat more than 382 million orders of fish and chips, the federation says.

Heavy Russian missile attacks hit Ukraine’s 2 largest cities

(AP) Ukraine’s two largest cities came under heavy Russian missile attacks on Tuesday, killing one person and injuring dozens. Oleh Syniehubov, the governor of the Kharkiv region, said one person died and 41 were injured in Russian missile strikes that hit the center of Kharkiv city and other areas. In Kyiv, the capital, five areas of the city were hit in the strikes and at least 12 people injured, according to mayor Vitali Klitschko. The barrage of the cities continued Russia’s escalated attacks on Ukraine in recent days that began on Friday with its largest single attack on Ukraine since the war started, in which at least 41 civilians were killed.

Myanmar’s ‘watermelons’: Soldier on the outside, rebel inside

(Reuters) For about two years, says 24-year-old Yan, a former Myanmar police officer, he risked his life pretending to serve the military junta while secretly spying for the armed resistance. “I freed myself from unfair orders,” he told Reuters from a room in a town near the Myanmar border where he said he was taking refuge after fleeing the country in April. Opposition groups said it was difficult to determine how many members of the security forces supplied information to the resistance, and their number was likely small given the risk, but they play a crucial role. They have supplied intelligence, including about the transportation of military supplies, that has helped opposition groups plan attacks, a spokesperson for People’s Goal, a group that supports defectors, told Reuters. Sources inside the security forces are known in Burmese as “watermelons”—green on the outside, appearing loyal to the army, but red, the colour of the ousted National League for Democracy government, on the inside.

China Is Pressing Women to Have More Babies. Many Are Saying No.

(WSJ) Chinese women have had it. Their response to Beijing’s demands for more children? No. Their refusal has set off a crisis for the Communist Party, which desperately needs more babies to rejuvenate China’s aging population. With the number of babies in free fall—fewer than 10 million were born in 2022, compared with around 16 million in 2012—China is headed toward a demographic collapse. China’s population, now around 1.4 billion, is likely to drop to just around half a billion by 2100, according to some projections. When Beijing said it would abolish its 35-year-old one-child policy in 2015, officials expected a baby boom. Instead, they got a baby bust.

South Korean opposition leader is stabbed in the neck by a knife-wielding man

(AP) South Korea’s tough-speaking liberal opposition leader, Lee Jae-myung, was stabbed in the neck by an unidentified knife-wielding man who attempted to kill him during his visit to the southeastern city of Busan, police said. Lee, 59, the head of the main opposition Democratic Party, was airlifted to a Seoul hospital for surgery after receiving emergency treatment in Busan. Police and emergency officials earlier said he was conscious after the attack and wasn’t in critical condition, but his exact status was unknown.

Planes collide and catch fire at Japan’s busy Haneda airport, killing 5

(NYT) A Japan Airlines flight carrying 367 passengers and 12 crew members collided with a Japan Coast Guard aircraft today while landing at an airport in Tokyo. The crash killed five Coast Guard members and caused the passenger jet to burst into flames. But the airline said that every person on the Japan Airlines plane was able to evacuate to safety. “The crew was spectacular in their reaction times,” one aviation expert said. “It really is a miracle.” The Coast Guard members had been en route to deliver supplies to the region affected by the powerful earthquake that struck western Japan yesterday, killing at least 55 people.

The U.S. and Israel: An Embrace Shows Signs of Strain After Oct. 7

(NYT) No other episode in the past half-century has tested the ties between the United States and Israel in such an intense and consequential way. The complicated diplomacy between Washington and Jerusalem since Hamas terrorists killed 1,200 people and seized 240 hostages has played out across both governments, in direct interactions between the leaders and intense back and forth between military and intelligence agencies. The relationship has grown increasingly fraught as Mr. Biden has involved himself more intensely in the conflict than almost any other issue in three years in office. Mr. Biden has seen growing internal resistance to his backing of Israel, including multiple dissent cables from State Department diplomats. In November, more than 500 political appointees and staff members representing some 40 government agencies sent a letter to Mr. Biden protesting his support of Israel’s war in Gaza. Congressional Democrats have been pressing him to curb Israel’s assault, and the United States has found itself at odds with other countries at the United Nations. The friction appears to be coming to a head as the new year arrives. The Biden team recognizes that its challenge is not just Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, since Israelis across the board support the military operation that according to the Gaza Health Ministry has killed more than 20,000 people. But there is no serious discussion inside the administration of a meaningful change in policy, like cutting off the arms supply to Israel.

Ethiopia signs pact to use Somaliland’s Red Sea port

(Reuters) Landlocked Ethiopia signed an initial agreement with Somalia’s breakaway region of Somaliland on Monday to use its Red Sea port of Berbera, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s office said. The Horn of Africa country currently relies on neighbouring Djibouti for most of its maritime trade. President Abdi said as part of the agreement, Ethiopia would also be the first country to recognise Somaliland as an independent nation in due course. Somaliland has not gained widespread international recognition despite declaring autonomy from Somalia in 1991. Somalia says Somaliland is part of its territory.

Books

(YouGov) A new poll found that 46 percent of Americans did not read a book in 2023 as of a December 16-18 poll. Overall, 26 percent of respondents reported reading between one and five books, 10 percent somewhere between six and 10 books, 8 percent between 11 and 20 books, and 11 percent more than 20 books so far. Indeed, the most active readers are reading a whole lot of books: 6 percent of respondents said they read over 40 books, a truly impressive stack.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A sneak peek at the biggest science news stories of 2023

https://sciencespies.com/space/a-sneak-peek-at-the-biggest-science-news-stories-of-2023/

A sneak peek at the biggest science news stories of 2023

What are you looking forward to reading about in 2023? Whether it is health, physics, technology or environment news, New Scientist will have you covered

Space

22 December 2022

By Jacob Aron

Engineers working on the Psyche spacecraft, which is set to launch in October 2023

Maxar

A fleet of rockets, new hope for the Amazon and an attempt to transform our diets are just some of the exciting stories that the New Scientist news team will be covering in 2023. Read on for our picks of the biggest science, technology, health and environment news you can expect to see in the coming year.

Space exploration

SpaceX’s Starship, the largest rocket ever built, is set to make its first orbital flight in 2023. It is just one of a fleet of huge rockets due to launch in the next 12 months, along with Blue Origin’s New Glenn. Both firms are owned by billionaires – Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos, respectively – who hope to shape the future of space travel.

Away from the private sector, government space agencies are also planning some exciting missions. The European Space Agency’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer will blast off in April and arrive at the Jupiter system in 2031, where it will explore Europa, Callisto and Ganymede for signs of habitability. NASA, meanwhile, is sending a spacecraft called Psyche to an asteroid, also called Psyche, that is believed to be the exposed iron core of a young planet. It will launch in October and arrive in 2029.

Advertisement

Closer to home, NASA is also gearing up to test its experimental X-59 plane, which is designed to break the sound barrier without creating a sonic boom and could lead to a renaissance for super-fast air travel.

Diseases

The fourth year of the coronavirus pandemic holds many uncertainties, not least as cases surge in China following the easing of its zero-covid strategy. One certainty is that we will need more and better vaccines to deal with emerging strains, though new jabs are unlikely to be approved as quickly as the first tranche, as regulatory approval will be slower.

Vaccines will also be needed to address the growing threat of avian flu, as the H5N1 virus continues to sweep through Europe and the US. These countries haven’t traditionally vaccinated poultry, as is done in places like Egypt and Hong Kong, but governments seem to be coming around to the idea.

Environment

In better news, defenders of the Amazon rainforest are in a cheery mood as we enter 2023. Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who takes office as president of Brazil on 1 January, has promised to reverse many of the measures put in place by his predecessor, Jair Bolsonaro, who had allowed rampant deforestation.

But even as the rainforest is saved, the oceans may be under a new threat in July 2023. If nations haven’t agreed an international code to regulate deep-sea mining by this point, governments and businesses eyeing the mineral wealth of the sea floor will be able to exploit these resources with few restrictions.

Technology

Government regulation will also play a key role in the field of artificial intelligence during 2023, with the European Union expected to finalise its Artificial Intelligence Act. This is the first attempt to create broad standards for the use of AI and aims to protect citizens of the EU from potentially harmful practices. Other nations and the tech giants will be watching closely, as European tech regulation has proved to be a global model for similar laws elsewhere.

Meanwhile, another group of Europeans is hoping to change the way we feed the world. Solar Foods, a company that uses renewable energy to turn carbon dioxide into a protein-rich powder, is set to open its first commercial-scale factory in Helsinki, Finland. The powder can be used in place of eggs and other sources of protein, and could drastically cut the water and land use involved in producing food.

Physics

Finally, it is a late Christmas for physicists, who will get two big toys to play with in 2023. First is the Linac Coherent Light Source-II, an upgrade of an existing facility in California that will turn it into the ultimate X-ray machine. Researchers hope to use it to make movies of the atoms inside molecules.

At the other end of the scale, a new gravitational wave hunter will also come online in 2023. The Matter-Wave Laser Interferometric Gravitation Antenna uses rubidium atoms chilled to such an extent that they become “matter waves”, able to tease out the ripples in space-time produced by colliding black holes and other massive objects. It will be able to detect events that our existing gravitational wave facilities have missed and could even help in the search for dark matter.

#Space

0 notes

Text

#EleNão

I never get tired of discussing politics. Online, I post my opinions, share ideas I find interesting, and I always try to be in the loop of what's happening around the globe as much as I can.

Most of the time, this much-needed exercise leaves me teary-eyed and broken-hearted. But THIS time, reading about the manifestations against Bolsonaro all around Brazil, I felt a profound sense of pride in my people.

Those of you who have been following me for some time probably know how much disgust I feel towards the current Brazilian president, Jair Bolsonaro.

(long post about Brazilian Politics after the cut. There's a list of amazing NGOs doing awesome work at the end of the text if you can/want to help the situation of the many groups at risk in Brazil right now. They include LGBTQIA+ groups, Indigenous people, Black communities, feminist movements, and NGOs focused on proper education and food for impoverished children).

In 2018, before the presidential elections, I was walking down Paulista Avenue with one of my closest friends.

Filling one of the widest avenues in Brazil, there was a mob of Bolsonaro supporters holding placards that read "É melhor Jair se acostumando." It's a small word-play with Bolsonaro's name; the idea is "You better start getting used to him". Stationed on the edges of the avenue, police officers stood with guns attached to their waists, crossed arms, and expressions that ranged from pure disinterest to clear enjoyment.

My friend stepped closer to me. He is strong, brilliant, and one of the bravest people I know, and yet he was clearly uncomfortable, so—after I managed to recover from the slight shock of seeing him like that—we linked our arms and avoided the mob in front of us, walking back to the intersection with Consolação Avenue.

Once we were away from the mob and the officers, he looked over his shoulders and sighed.

"If you weren't here, they'd probably have stopped me," he said.

The mob was mostly White. I'm White.

My friend is Black.

"I don't wanna think what will happen if that dude wins the elections," he completed.

His fear was justified. Bolsonaro is a racist, misogynist, homophobic ex-military who preaches in favor of the Military Dictatorship period in Brazil, which killed thousands of Black and Indigenous people while also torturing anyone who spoke up against the military government.

"He won't win," I answered. I was born and raised in São Paulo, one of Brazil's industrial, technological, and cultural hubs; I never thought people would turn a blind eye to how much damage Bolsonaro could make as a president. "He can't win," I added. "Not being who he is."

My friend nodded. We hugged and walked and laughed it off (tried to). And when Bolsonaro won, we both cried.

I guess I was a tad too naïve.

He won. He won, and I never got used to the idea of having such a terrible president. Here are a few things that happened in his government and that are directly connected to him:

(most of the links here are from news articles in Portuguese)

The number of neo-nazism sites in favor of white supremacy increased 400% in Brazil in 2020 compared to the same period in 2018 (before Bolsonaro was elected); this is one of the many consequences of his numerous racist speeches and a small proof of just how racist Brazil is.

The number of military police attacks on low-income communities increased along with the number of COVID deaths.

While, since February 2019, the world already knows that the rights of LGBTQIA+ people are threatened under the current far-right government, the advances in LGBTQIA+ rights n Brazil stopped after Bolsonaro was elected, and instead, there was a movement of retrocession.

The fires in the Amazon Forest further increased by 43% in April 2021 (in 2019, after an increase of 63% in comparison to 2018, I wrote about one of the most terrifying fires in Amazon and how I could see the smoke from it from my home in São Paulo, 3000 km away).

After promising to diminish deforestation in order to receive a large sum of money from the US, the Brazilian Senate is preparing to vote for a new Law Project that tries to make the licensing of land in the Amazon Forest more pliable. That means it'd be disgustingly easier for people to buy and explore the lands that should belong to the Brazilian indigenous people; all they'd need is an auto-declaratory license emitted online without the analysis of any environmental body.

Under the pretext of "helping" the indigenous people, Bolsonaro defends mining and agriculture in indigenous peoples' lands. This is one of the public declarations of repudiation written by the Yanomami people (one of the biggest indigenous communities in Brazil) about Bolsonaro and his visit to their land on May 27th, 2021.

And then we have women's situation, which you can see in the Brazilian annual of Public Security.

And this is just the tip of the iceberg. I didn't add the investigations of corruption (including embezzlement of money for COVID-related services), the liberation of guns, the nepotism, the problem with vaccines, the damage of the far-right religious institutions the president supports, and the disrespect and verbal aggression towards women.

... And that's why I felt so proud of my fellow Brazilians yesterday. :3 We're a young people (Brazil is only 521 years old, while England, for example, is 1094, if you think about the creation of the kingdom of England), but we're still doing our best. I might be away from my Land of Drizzle, but I carry my people in my heart, and I cry alongside them, as loud as I can,

♥♥♥ Fora Bolsonaro! ♥♥♥

---

And even though I can see Brazilians waking up and organizing themselves better, there are still people needing our help right now. If you want to help the situation in Brazil, please consider Donating! Here's a small list of NGOs doing a lot of good in Brazil:

+ APIB ("Brazilian Indigenous People Articulation") - to help the indigenous people in Brazil. (They also have a fantastic documentary subtitled in English you can watch here, showing the situation of the indigenous people in Brazil)

+ CUFA ("Unified Central of Favelas") - to help the impoverished communities and Favelas in Brazil. (I use my credit card to donate to this one; if you're outside Brazil, I think this might work for you too). If you want to help the Covid Relief specifically, CUFA has a project called "Mães da Favela" (Favela mothers), which you can donate to directly through this link.

+ Amigos do Bem - help with famine, donate drinkable water, and improve education in northeast Brazil, one of the areas more impacted by droughts.

+ Omolará (site in Portuguese) - amazing social project focusing on helping Black Woman find education and financial independence.

+ To help the LGBT+ community in Brazil, I'm still searching for NGOs and projects that receive international donations. If you're in Brazil or if you can make wire transfers, I suggest checking this list of fantastic projects (in Portuguese).

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pandemic pushes new homeless onto São Paulo's streets

São Paulo is facing a homelessness crisis, as recent prices become too heavy of a burden for an increasingly impoverished population.

[Image description: a homeless family is seen by tents at Patio do Colegio, in São Paulo downtown, Brazil, on August 19, 2021.]

When Monica's landlord suddenly doubled the rent on the room where she lived with her three daughters in São Paulo, she says they had little choice but to go live on the streets.

Like a growing number of poor people in Brazil's economic capital, Monica has fallen on bitter times during the Covid-19 pandemic, forcing her to choose between feeding or housing herself and her girls, ages 12, nine and two.

"If we spend everything on the rent, how are we going to fill our stomachs? People need more than just a roof over their heads, right?" said Monica, 33, who set up an impromptu camp for the family a week ago at Republic Square, in the heart of this sprawling concrete jungle of 12 million people.

She spends her days collecting and selling recyclable materials, earning around 20 to 30 reais (about US$4 to US$6) a day, before picking her daughters up at school, she said.

Surging unemployment and rising prices, especially for housing, during the pandemic have pushed numerous people like her into the streets.

"There's been a very big increase in the number of people living on the streets for the first time," said Kelseny Medeiros Pinho, of the University of São Paulo's human-rights clinic. "If you lose your job and you don't have any alternative, the street is your only answer."

It hasn't helped, she said, that President Jair Bolsonaro's government cut emergency Covid-19 assistance to the poor from 600 reais to 150 reais (around US$28) this year.

The far-right president and Sao Paulo's governor both vetoed legislation that would have put a moratorium on evictions during the health crisis.

Across Brazil, at least 14,300 families were evicted from March 2020 to June 2021, and another 85,000 are threatened with eviction, according to the organisation Zero Evictions (Despejo Zero).

Continue reading.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

TTalk of Bolsonaro, Trump, racism, death among many other under the cut

I'm not one to be very political on main, but Jesus fuck, Bolsonaro is like a fucking Trump from Brasil, I can't do this anymore,, the guy is so pathetic, everything he says or does is incredibly stupid and moronic

Americans were able to get a chance and I'm honestly happy for them, they don't have someone AS incompetent on control

But me, a Brasilian, have a sexist, racist, homophobic and so on, person "taking care" of the country... He's let thousands of people die, wether of Covid, starvation or poverty, he's not a good person and shoves the blame on others, and if you think for a second he's done anything right, he didn't

It's exhausting for people such as myself to have to explain why he isn't great at all, but still have people support him nonetheless

He's done such a great job*(/s) that there's at least 560K people dead, and you might as well say "B-But there's also many people that recovered!!!!" fucking HELL A FUCKING GENOCIDE HAPPENED HERE AND THOSE PEOPLE ARE STILL GOING TO BE MISERABLE FOR THE REST OF THEIR LIVES AND IM THANKFUL THEY'RE ALIVE BUT THAT DOESN'T FUCKING JUSTIFY OR BASICALLY EXCUSE HIM FOR THE DEATHS HE CAUSED

I'm just tired

I love my country, i really do, but I dont like the people governing it,,,

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

Like the US president, Jair Bolsonaro has raged against the quarantine implemented by his own government and has just dismissed his level-headed health minister, Luiz Henrique Mandetta. A few days after the first shutdown measures were announced in São Paulo, the president blatantly defied them by encouraging his supporters to attend a mass rally on March 15, filling part of the megalopolis’s wide Avenida Paulista in support of Bolsonaro and against Congress. Covid-19 is just a gripezinha (sniffle), he insists, while heading a campaign on social media to reopen the economy under the slogan “Brazil cannot close.” On Sunday, he headed a second small rally in the capital of Brasília, where social distancing was replaced by manic jostling to get close to the president, along with chants demanding that the army intervene to get people back to work.

Bolsonaro has dismissed as “hysteria” the lockdown measures, implemented swiftly in Brazil despite the president’s rhetoric. “Let’s face the virus like men, not kids,” he urged, as he visited a Brasília street market last month. Perhaps the only head of state able to out-Trump Trump in sheer recklessness and social-networked delirium, Bolsonaro has mobilized his three loyal sons, two of them members of Congress, to help peddle conspiracy theories concerning China and snake-oil remedies such as chloroquine. Ironically, Bolsonaro, 66, was lucky to escape infection on March 7, when he attended a neoconservative get-together hosted by Trump at his Mar-a-Lago mansion in Palm Beach, after which several members of the Brazilian delegation came down with severe symptoms.

The terrifying implications of such a cavalier approach to the pandemic in a country with a stretched health care system and vast slum cities where social isolation, and even the routine precaution of washing hands, is an impossible challenge, soon forced the Brazilian establishment into action. When Bolsonaro—following the Trumpian script—announced that he would reverse the lockdowns in São Paulo, Rio, and other cities, the Supreme Court reiterated that under Brazil’s federal system, it is state and city authorities who decide such matters. Leaders of both the Senate and Chamber of Deputies supported Mandetta, while governors like João Doria in São Paulo and Wilson Witzel in Rio—allies of Bolsonaro in the presidential elections of 2018—maintained the city lockdowns. Justice minister and super judge Sérgio Moro, who led the “car wash” anti-corruption probe and sentenced former president Lula da Silva to nine years in prison, dared to defy the president whom he had helped into power.

The other super minister in the Bolsonaro government, billionaire financier Paulo Guedes, whose global investment funds are now staring into the abyss, also seemed skeptical of Bolsonaro’s antics, despite his concern that the lockdowns and a pandemic-driven 5 percent drop in GDP this year (an IMF forecast) might scupper his plans to privatize the Brazilian economy. Pots and pans were banged from the balconies of locked-down apartment blocks in middle-class districts of Rio and São Paulo in protest against Bolsonaro, just as they had been five or six years before against the soon-to-be-impeached President Dilma Rousseff. Like Trump’s health adviser Anthony Fauci, also a doctor, Mandetta had emerged as a voice of reason, with better ratings in the polls than Bolsonaro’s, and appeared to have cleverly outmaneuvered the president. At least, until his dismissal last week.

Even the armed forces—well represented in the Bolsonaro cabinet—seemed prepared to intervene against the madness of President Jair, despite the Bolsonaristas’ calls for military action in favor of the president. A report in DefesaNet, an online media outlet used by the military to get its message out, said that effective control of the government’s strategy on Covid-19 had devolved to the chief of staff, Gen. Walter Souza Braga Netto. “The president will thus be able to behave democratically as if he did not belong to his own government,” explained DefesaNet, a contorted phrase that perfectly captures the Brazilian establishment and military’s paternal approach to Bolsonaro’s childish outbursts.

When Mandetta was confirmed in his post after Bolsonaro’s initial threats to oust him, many concluded that the lunatic had been removed from control of the asylum, or at least the intensive care ward. “The general feeling here is that Bolsonaro is a puppet,” remarked an employee early last week at the country’s state development bank, BNDES, whose role in successfully fending off the global economic crisis in 2009 will be sorely missed this time, after Guedes’s decision to downsize it. But the removal of Mandetta, and Bolsonaro’s paranoid appeal to his base Friday to help him fight off an alleged coup attempt orchestrated by Doria in São Paulo and Rodrigo Maia, the head of the Chamber of Deputies, suggest an alternate reading. Could the president glimpse opportunity in the chaos?

“There is method in the madness,” explained the anthropologist Luiz Eduardo Soares in an interview. Soares is co-author of Elite da Tropa, a gripping 2006 account of police brutality and extreme-right-wing death squads in Rio’s favelas that was turned into two blockbuster films, Elite Squad and Elite Squad 2. Soares, whose latest book, O Brasil e Seu Duplo (Brazil and Its Duplicate), explores the origins of Bolsonaro and Brazilian neofascism, says Covid-19 will either stop the Bolsonaro project in its tracks or accelerate its progress. “Bolsonaro has been advised to deny the threat of the pandemic,” said Soares. “He feels sure of himself, in part because he’s mimicking Trump. But his authority has diminished, and he’s in danger of becoming a lame-duck president only a year into his term.”

But the president has a plan. Behaving, as the generals suggested, “as if he did not belong to his own government,” Bolsonaro may be able to escape the blame for the devastating economic crisis now unfolding. A brutal recession triggered, as elsewhere, by the pandemic, comes after seven years of stagnation. Even before the pandemic, 60 million Brazilians had fallen back into poverty (defined as earning less than $5 a day) after the advances of the Lula years. “The plan is to transfer responsibility and accuse the others for allowing the tremendous crisis which we are going to encounter,” said Soares.

The worsening social conditions will undoubtedly create fertile ground for Bolsonaro’s bid to capitalize on discontent. A survey cited by piauí magazine found that 72 percent of Brazilians have enough savings to cushion lost earnings for just one week before entering serious hardship, and 32 percent already report problems buying essential goods like food. “We are staying in, but food is scarce, and without work there is no money,” said a mother of two who lives in the enormous Rio favela of Rocinha, where at least 50,000 inhabitants are packed into the hillside above Ipanema and Leblon. “Practically everybody in the favela works in the informal economy, so the lockdown doesn’t really apply here; businesses are open but close earlier. People are wearing masks; there is little information,” said Macarrao, a rapper from Cinco Bocas, a favela in the North Zone of Rio, whose daughter has Covid-19. “She got treatment fairly quickly,” he added. This may not be the case now. Epidemiologists at five important institutes in Brazil forecast recently that the health system could reach the point of collapse by late April.

The Bolsonaro government has guaranteed a basic monthly income of 600 reales ($112) to those with no income, but the electronic application has failed, and long lines of people—practicing scant social distancing—have waited outside the public savings bank Caixa Econômica, only to discover that their transfer has not arrived. In any case, $4 a day is a pittance, and Guedes seems reluctant to take any other measures to soften the blow for Brazil’s poor, even though he has passed tax cuts for business. There is a logical link to Guedes’s neoliberal stance, as millions descend into poverty and hunger, and Bolsonaro’s populist plan to blame it all on Mandetta and the governors of the two big cities: Both governors are potential rivals for the next presidential elections, and Bolsonaro will use his media to pinpoint them as responsible for the hardship.

While registered cases of the coronavirus in Brazil are 40,000, the real figure is probably over 10 times that, as indicated by the current unnaturally high mortality rate. According to official data, by the end of last week some 2,600 people had died from the virus—low compared with Europe and the United States, but Brazil is late in the curve. And Brazil’s intensive care units are fast approaching capacity, just as they have in Europe. Manaus, the Amazon metropolis where the reports of contagion in the indigenous territories make harrowing reading, is already at 100 percent capacity and is transferring patients to other sites. A survey by the University of Pelotas in Rio Grande do Sul, in the south of the country, estimates that there are at least seven times more cases than the official figures suggest.

Bolsonaro will try to build a strategy from his base of support among evangelicals and people in the orbit of the police and military. Evangelicals have been another element of the Covid-19 denial, but they are fired by conviction rather than nonchalance. Edir Macedo, the billionaire pastor whose TV networks are used by Bolsonaro in preference to the establishment Rede Globo, said the WHO’s warnings on Covid-19 were the “work of Satan.” “Our position from the first moment has been to keep the churches open, because God will defeat the virus,” said Washington Reis, the evangelical mayor of the Rio working-class district of Duque de Caxias last week. Days later, God had spoken, and Reis was hospitalized with Covid-19. The tactic may be working. Bolsonaro appears to have maintained support in the pandemic, despite the pot banging and international horror at his stance. A poll by Datafolha last week showed that 36 percent of Brazilians believe his management of the health crisis is “good or great,” slightly more support than before the pandemic. And 52 percent say he’s capable of leading the country through the crisis.

There may even be a second phase to Bolsonaro’s strategy of leveraging Covid-19 to stay in power, said Soares. “Building on the contradictions of his own government and the coming crisis in the health system and the economy, Bolsonaro may be hoping for some kind of a social explosion in the streets,” he said. “That would create the conditions for a state of emergency and the end of democratic institutions that are still blocking the path of Bolsonaro’s basic project: a dictatorship and the perpetuation in power of his family.”

The call for a coup against Congress—pitched, at Sunday’s rally, at more extremist elements in the armed forces—may be a first step in this direction. By first denouncing an alleged coup plot against his own presidency, allegedly planned by Congress and the big-city governors, and then calling for military action in his defense, “Bolsonaro is following the example of many authoritarian presidents, starting with Hitler in 1933,” writes Nabil Bonduki, former São Paulo culture secretary, in an article in Folha de S.Paulo. “The allegation of an attempted coup is thus the pretext for a coup planned by the president himself.” The idea might sound fanciful, and as paranoid as Bolsonaro’s own rhetoric. But the former army captain was a reluctant recruit to democratic politics even before the devastating arrival of Covid-19.

Bolsonaro’s close links to right-wing militias made up of former military police and firemen, which run whole swaths of the West Zone of Rio, may help. “The militias have always been close to the Bolsonaro family, and now they are becoming more ideological, part of a Bolsonarist movement. They could help in a coup if he wants that,” said Soares. The militia Escritório do Crime (the Crime Office) is known to be implicated in the assassination of left-wing Rio city councilor Marielle Franco over two years ago. To square the circle of fascism and Covid-19, reports are just out that the militias in Itanhangá and Rio das Pedras, adjacent to the kitsch beach resort of Barra da Tijuca, where the Bolsonaro family has its base, are forcing businesses to stay open during the lockdown so they can continue to charge for protection.

as ian kershaw points out, the latin american cold war governments that were called fascism don’t really correspond with the italian and german examples because they lack the mass movements that brought hitler and mussolini to power. they, like salazar and franco, used symbols of fascism to exude power, but did not share the key characteristics of the movement. for instance, the nazi party numbered in the hundreds of thousands before it took power, while the falange only had 10,000 members at the outbreak of the spanish civil war. bolsonaro, in contrast, has a mass movement behind him, with the parties that back him having membership in the millions. his supporters are not older men, like most conservatives, but men in their 20s and 30s who are willing to go out and rally and brawl for him. like nazis, they have developed an intellectualized but conspiratorial and religiously-imbued notion of national salvation from international threats. they are often armed and control territory, with more favelas actually being under control of paramilitary groups than drug gangs.

on the other hand, many definitions of fascism, particularly on the left, require an economic component. a crude form of trotsky’s theory of fascism essentially labels these groups as pinkertons who took over a state, who come when the rate of profit is low and force labour to give up more of its share of national income. brazil is indeed experiencing a low rate of profit, but its labour movement is not well organized enough to seriously defend its prerogatives from a traditional state-backed approach. it can be pointed out that PT, which was attempting such an approach, was removed from power by those who viewed the party as defenders of labour. this grouping, based in the traditional military power centres of the brazilian regime, did not have any real support on their own among the brazilian populace, with temer’s government having a 5% approval rating. bolsonaro was seized upon by this grouping because it offered the chance for a government that largely agreed with its goals but could muster a far greater base of support among the populace. this partially mirrors the rise of hitler, who was also seen by supporters of the former military dictatorship as their ticket back into such a situation. the combination of hitler’s love of the military contrasted with the disdain of him by actual military figures (hindenburg called him “the little corporal”) can be seen in the current bolsonaro-generals dynamic. it took the nazi party leadership a year and a half to subsume the military to its own prerogatives, while bolsonaro has done far less in that time. however, bolsonaro’s base has been primed for a coup they view as a countercoup, with rumours of a military takeover having spread across the pro-bolsonaro blogosphere starting in march along with rhetoric of defending him from such an event.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

What will the world be like after coronavirus? Four possible futures

by Simon Mair

Where will we be in six months, a year, ten years from now? I lie awake at night wondering what the future holds for my loved ones. My vulnerable friends and relatives. I wonder what will happen to my job, even though I’m luckier than many: I get good sick pay and can work remotely. I am writing this from the UK, where I still have self-employed friends who are staring down the barrel of months without pay, friends who have already lost jobs. The contract that pays 80% of my salary runs out in December. Coronavirus is hitting the economy badly. Will anyone be hiring when I need work?

There are a number of possible futures, all dependent on how governments and society respond to coronavirus and its economic aftermath. Hopefully we will use this crisis to rebuild, produce something better and more humane. But we may slide into something worse.

I think we can understand our situation – and what might lie in our future – by looking at the political economy of other crises. My research focuses on the fundamentals of the modern economy: global supply chains, wages, and productivity. I look at the way that economic dynamics contribute to challenges like climate change and low levels of mental and physical health among workers. I have argued that we need a very different kind of economics if we are to build socially just and ecologically sound futures. In the face of COVID-19, this has never been more obvious.

The responses to the COVID-19 pandemic are simply the amplification of the dynamic that drives other social and ecological crises: the prioritisation of one type of value over others. This dynamic has played a large part in driving global responses to COVID-19. So as responses to the virus evolve, how might our economic futures develop?

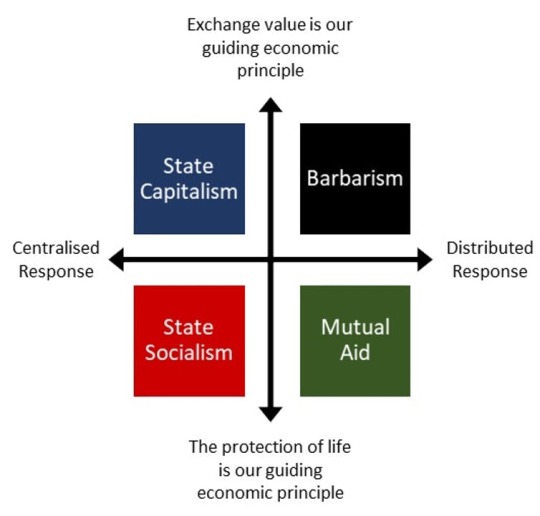

From an economic perspective, there are four possible futures: a descent into barbarism, a robust state capitalism, a radical state socialism, and a transformation into a big society built on mutual aid. Versions of all of these futures are perfectly possible, if not equally desirable.

What might our future hold? Jose Antonio Gallego Vázquez/Unsplash, FAL

Small changes don’t cut it

Coronavirus, like climate change, is partly a problem of our economic structure. Although both appear to be “environmental” or “natural” problems, they are socially driven.

Yes, climate change is caused by certain gases absorbing heat. But that’s a very shallow explanation. To really understand climate change, we need to understand the social reasons that keep us emitting greenhouse gases. Likewise with COVID-19. Yes, the direct cause is the virus. But managing its effects requires us to understand human behaviour and its wider economic context.

Tackling both COVID-19 and climate change is much easier if you reduce nonessential economic activity. For climate change this is because if you produce less stuff, you use less energy, and emit fewer greenhouse gases. The epidemiology of COVID-19 is rapidly evolving. But the core logic is similarly simple. People mix together and spread infections. This happens in households, and in workplaces, and on the journeys people make. Reducing this mixing is likely to reduce person-to-person transmission and lead to fewer cases overall.

This article is part of Conversation Insights

The Insights team generates long-form journalism derived from interdisciplinary research. The team is working with academics from different backgrounds who have been engaged in projects aimed at tackling societal and scientific challenges.

Reducing contact between people probably also helps with other control strategies. One common control strategy for infectious disease outbreaks is contact tracing and isolation, where an infected person’s contacts are identified, then isolated to prevent further disease spread. This is most effective when you trace a high percentage of contacts. The fewer contacts a person has, the fewer you have to trace to get to that higher percentage.

We can see from Wuhan that social distancing and lockdown measures like this are effective. Political economy is useful in helping us understand why they weren’t introduced earlier in European countries and the US.

A fragile economy

Lockdown is placing pressure on the global economy. We face a serious recession. This pressure has led some world leaders to call for an easing of lockdown measures.

Even as 19 countries sat in a state of lockdown, the US president, Donald Trump, and Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro called for roll backs in mitigation measures. Trump called for the American economy to get back to normal in three weeks (he has now accepted that social distancing will need to be maintained for much longer). Bolsonaro said: “Our lives have to go on. Jobs must be kept … We must, yes, get back to normal.”

In the UK meanwhile, four days before calling for a three-week lockdown, Prime Minister Boris Johnson was only marginally less optimistic, saying that the UK could turn the tide within 12 weeks. Yet even if Johnson is correct, it remains the case that we are living with an economic system that will threaten collapse at the next sign of pandemic.

The economics of collapse are fairly straightforward. Businesses exist to make a profit. If they can’t produce, they can’t sell things. This means they won’t make profits, which means they are less able to employ you. Businesses can and do (over short time periods) hold on to workers that they don’t need immediately: they want to be able to meet demand when the economy picks back up again. But, if things start to look really bad, then they won’t. So, more people lose their jobs or fear losing their jobs. So they buy less. And the whole cycle starts again, and we spiral into an economic depression.

In a normal crisis the prescription for solving this is simple. The government spends, and it spends until people start consuming and working again. (This prescription is what the economist John Maynard Keynes is famous for).

But normal interventions won’t work here because we don’t want the economy to recover (at least, not immediately). The whole point of the lockdown is to stop people going to work, where they spread the disease. One recent study suggested that lifting lockdown measures in Wuhan (including workplace closures) too soon could see China experience a second peak of cases later in 2020.

As the economist James Meadway wrote, the correct COVID-19 response isn’t a wartime economy – with massive upscaling of production. Rather, we need an “anti-wartime” economy and a massive scaling back of production. And if we want to be more resilient to pandemics in the future (and to avoid the worst of climate change) we need a system capable of scaling back production in a way that doesn’t mean loss of livelihood.

So what we need is a different economic mindset. We tend to think of the economy as the way we buy and sell things, mainly consumer goods. But this is not what an economy is or needs to be. At its core, the economy is the way we take our resources and turn them into the things we need to live. Looked at this way, we can start to see more opportunities for living differently that allow us to produce less stuff without increasing misery.

I and other ecological economists have long been concerned with the question of how you produce less in a socially just way, because the challenge of producing less is also central to tackling climate change. All else equal, the more we produce the more greenhouse gases we emit. So how do you reduce the amount of stuff you make while keeping people in work?

Proposals include reducing the length of the working week, or, as some of my recent work has looked at, you could allow people to work more slowly and with less pressure. Neither of these is directly applicable to COVID-19, where the aim is reducing contact rather than output, but the core of the proposals is the same. You have to reduce people’s dependence on a wage to be able to live.

What is the economy for?

The key to understanding responses to COVID-19 is the question of what the economy is for. Currently, the primary aim of the global economy is to facilitate exchanges of money. This is what economists call “exchange value”.

The dominant idea of the current system we live in is that exchange value is the same thing as use value. Basically, people will spend money on the things that they want or need, and this act of spending money tells us something about how much they value its “use”. This is why markets are seen as the best way to run society. They allow you to adapt, and are flexible enough to match up productive capacity with use value.

What COVID-19 is throwing into sharp relief is just how false our beliefs about markets are. Around the world, governments fear that critical systems will be disrupted or overloaded: supply chains, social care, but principally healthcare. There are lots of contributing factors to this. But let’s take two.

First, it is quite hard to make money from many of the most essential societal services. This is in part because a major driver of profits is labour productivity growth: doing more with fewer people. People are a big cost factor in many businesses, especially those that rely on personal interactions, like healthcare. Consequently, productivity growth in the healthcare sector tends to be lower than the rest of the economy, so its costs go up faster than average.

Second, jobs in many critical services aren’t those that tend to be highest valued in society. Many of the best paid jobs only exist to facilitate exchanges; to make money. They serve no wider purpose to society: they are what the anthropologist David Graeber calls “bullshit jobs”. Yet because they make lots of money we have lots of consultants, a huge advertising industry and a massive financial sector. Meanwhile, we have a crisis in health and social care, where people are often forced out of useful jobs they enjoy, because these jobs don’t pay them enough to live.

Bullshit jobs are innumerable. Jesus Sanz/Shutterstock.com

Pointless jobs

The fact that so many people work pointless jobs is partly why we are so ill prepared to respond to COVID-19. The pandemic is highlighting that many jobs are not essential, yet we lack sufficient key workers to respond when things go bad.

People are compelled to work pointless jobs because in a society where exchange value is the guiding principle of the economy, the basic goods of life are mainly available through markets. This means you have to buy them, and to buy them you need an income, which comes from a job.

The other side of this coin is that the most radical (and effective) responses that we are seeing to the COVID-19 outbreak challenge the dominance of markets and exchange value. Around the world governments are taking actions that three months ago looked impossible. In Spain, private hospitals have been nationalised. In the UK, the prospect of nationalising various modes of transport has become very real. And France has stated its readiness to nationalise large businesses.

Likewise, we are seeing the breakdown of labour markets. Countries like Denmark and the UK are providing people with an income in order to stop them from going to work. This is an essential part of a successful lockdown. These measures are far from perfect. Nonetheless, it is a shift from the principle that people have to work in order to earn their income, and a move towards the idea that people deserve to be able to live even if they cannot work.

This reverses the dominant trends of the last 40 years. Over this time, markets and exchange values have been seen as the best way of running an economy. Consequently, public systems have come under increasing pressures to marketise, to be run as though they were businesses who have to make money. Likewise, workers have become more and more exposed to the market – zero-hours contracts and the gig economy have removed the layer of protection from market fluctuations that long term, stable, employment used to offer.

COVID-19 appears to be reversing this trend, taking healthcare and labour goods out of the market and putting it into the hands of the state. States produce for many reasons. Some good and some bad. But unlike markets, they do not have to produce for exchange value alone.

These changes give me hope. They give us the chance to save many lives. They even hint at the possibility of longer term change that makes us happier and helps us tackle climate change. But why did it take us so long to get here? Why were many countries so ill-prepared to slowdown production? The answer lies in a recent World Health Organisation report: they did not have the right “mindset”.

Our economic imaginations

There has been a broad economic consensus for 40 years. This has limited the ability of politicians and their advisers to see cracks in the system, or imagine alternatives. This mindset is driven by two linked beliefs:

The market is what delivers a good quality of life, so it must be protected

The market will always return to normal after short periods of crisis

These views are common to many Western countries. But they are strongest in the UK and the US, both of which have appeared to be badly prepared to respond to COVID-19.

In the UK, attendees at a private engagement reportedly summarised the Prime Minister’s most senior aide’s approach to COVID-19 as “herd immunity, protect the economy, and if that means some pensioners die, too bad”. The government has denied this, but if real, it’s not surprising. At a government event early in the pandemic, a senior civil servant said to me: “Is it worth the economic disruption? If you look at the treasury valuation of a life, probably not.”

This kind of view is endemic in a particular elite class. It is well represented by a Texas official who argued that many elderly people would gladly die rather than see the US sink into economic depression. This view endangers many vulnerable people (and not all vulnerable people are elderly), and, as I have tried to lay out here, it is a false choice.

One of the things the COVID-19 crisis could be doing, is expanding that economic imagination. As governments and citizens take steps that three months ago seemed impossible, our ideas about how the world works could change rapidly. Let us look at where this re-imagining could take us.

Four futures

To help us visit the future, I’m going to use a technique from the field of futures studies. You take two factors you think will be important in driving the future, and you imagine what will happen under different combinations of those factors.

The factors I want to take are value and centralisation. Value refers to whatever is the guiding principle of our economy. Do we use our resources to maximise exchanges and money, or do we use them to maximise life? Centralisation refers to the ways that things are organised, either by of lots of small units or by one big commanding force. We can organise these factors into a grid, which can then be populated with scenarios. So we can think about what might happen if we try to respond to the coronavirus with the four extreme combinations:

1) State capitalism: centralised response, prioritising exchange value

2) Barbarism: decentralised response prioritising exchange value

3) State socialism: centralised response, prioritising the protection of life

4) Mutual aid: decentralised response prioritising the protection of life.

The four futures. © Simon Mair, Author provided

State capitalism

State capitalism is the dominant response we are seeing across the world right now. Typical examples are the UK, Spain and Denmark.

The state capitalist society continues to pursue exchange value as the guiding light of the economy. But it recognises that markets in crisis require support from the state. Given that many workers cannot work because they are ill, and fear for their lives, the state steps in with extended welfare. It also enacts massive Keynesian stimulus by extending credit and making direct payments to businesses.

The expectation here is that this will be for a short period. The primary function of the steps being taken is to allow as many businesses as possible to keep on trading. In the UK, for example, food is still distributed by markets (though the government has relaxed competition laws). Where workers are supported directly, this is done in ways that seek to minimise disruption of normal labour market functioning. So, for example, as in the UK, payments to workers have to be applied for and distributed by employers. And the size of payments is made on the basis of the exchange value a worker usually creates in the market, rather than the usefulness of their work.

Could this be a successful scenario? Possibly, but only if COVID-19 proves controllable over a short period. As full lockdown is avoided to maintain market functioning, transmission of infection is still likely to continue. In the UK, for instance, non-essential construction is still continuing, leaving workers mixing on building sites. But limited state intervention will become increasingly hard to maintain if death tolls rise. Increased illness and death will provoke unrest and deepen economic impacts, forcing the state to take more and more radical actions to try to maintain market functioning.

Barbarism

This is the bleakest scenario. Barbarism is the future if we continue to rely on exchange value as our guiding principle and yet refuse to extend support to those who get locked out of markets by illness or unemployment. It describes a situation that we have not yet seen.

Businesses fail and workers starve because there are no mechanisms in place to protect them from the harsh realities of the market. Hospitals are not supported by extraordinary measures, and so become overwhelmed. People die. Barbarism is ultimately an unstable state that ends in ruin or a transition to one of the other grid sections after a period of political and social devastation.

Could this happen? The concern is that either it could happen by mistake during the pandemic, or by intention after the pandemic peaks. The mistake is if a government fails to step in in a big enough way during the worst of the pandemic. Support might be offered to businesses and households, but if this isn’t enough to prevent market collapse in the face of widespread illness, chaos would ensue. Hospitals might be sent extra funds and people, but if it’s not enough, ill people will be turned away in large numbers.

Potentially just as consequential is the possibility of massive austerity after the pandemic has peaked and governments seek to return to “normal”. This has been threatened in Germany. This would be disastrous. Not least because defunding of critical services during austerity has impacted the ability of countries to respond to this pandemic.

The subsequent failure of the economy and society would trigger political and social unrest, leading to a failed state and the collapse of both state and community welfare systems.

youtube

State socialism

State socialism describes the first of the futures we could see with a cultural shift that places a different kind of value at the heart of the economy. This is the future we arrive at with an extension of the measures we are currently seeing in the UK, Spain and Denmark.

The key here is that measures like nationalisation of hospitals and payments to workers are seen not as tools to protect markets, but a way to protect life itself. In such a scenario, the state steps in to protect the parts of the economy that are essential to life: the production of food, energy and shelter for instance, so that the basic provisions of life are no longer at the whim of the market. The state nationalises hospitals, and makes housing freely available. Finally, it provides all citizens with a means of accessing various goods – both basics and any consumer goods we are able to produce with a reduced workforce.

Citizens no longer rely on employers as intermediaries between them and the basic materials of life. Payments are made to everyone directly and are not related to the exchange value they create. Instead, payments are the same to all (on the basis that we deserve to be able to live, simply because we are alive), or they are based on the usefulness of the work. Supermarket workers, delivery drivers, warehouse stackers, nurses, teachers, and doctors are the new CEOs.

It’s possible that state socialism emerges as a consequence of attempts at state capitalism and the effects of a prolonged pandemic. If deep recessions happen and there is disruption in supply chains such that demand cannot be rescued by the kind of standard Keynesian policies we are seeing now (printing money, making loans easier to get and so on), the state may take over production.

There are risks to this approach – we must be careful to avoid authoritarianism. But done well, this may be our best hope against an extreme COVID-19 outbreak. A strong state able to marshal the resources to protect the core functions of economy and society.

Mutual aid

Mutual aid is the second future in which we adopt the protection of life as the guiding principle of our economy. But, in this scenario, the state does not take a defining role. Rather, individuals and small groups begin to organise support and care within their communities.

The risks with this future is that small groups are unable to rapidly mobilise the kind of resources needed to effectively increase healthcare capacity, for instance. But mutual aid could enable more effective transmission prevention, by building community support networks that protect the vulnerable and police isolation rules. The most ambitious form of this future sees new democratic structures arise. Groupings of communities that are able to mobilise substantial resources with relative speed. People coming together to plan regional responses to stop disease spread and (if they have the skills) to treat patients.

This kind of scenario could emerge from any of the others. It is a possible way out of barbarism, or state capitalism, and could support state socialism. We know that community responses were central to tackling the West African Ebola outbreak. And we already see the roots of this future today in the groups organising care packages and community support. We can see this as a failure of state responses. Or we can see it as a pragmatic, compassionate societal response to an unfolding crisis.

Hope and fear

These visions are extreme scenarios, caricatures, and likely to bleed into one another. My fear is the descent from state capitalism into barbarism. My hope is a blend of state socialism and mutual aid: a strong, democratic state that mobilises resources to build a stronger health system, prioritises protecting the vulnerable from the whims of the market and responds to and enables citizens to form mutual aid groups rather than working meaningless jobs.

What hopefully is clear is that all these scenarios leave some grounds for fear, but also some for hope. COVID-19 is highlighting serious deficiencies in our existing system. An effective response to this is likely to require radical social change. I have argued it requires a drastic move away from markets and the use of profits as the primary way of organising an economy. The upside of this is the possibility that we build a more humane system that leaves us more resilient in the face of future pandemics and other impending crises like climate change.

Social change can come from many places and with many influences. A key task for us all is demanding that emerging social forms come from an ethic that values care, life, and democracy. The central political task in this time of crisis is living and (virtually) organising around those values.

About The Author:

Simon Mair is a Research Fellow in Ecological Economics at the Centre for the Understanding of Sustainable Prosperity, University of Surrey

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

21 notes

·

View notes

Quote

A team of 85 Cuban doctors and nurses arrived in Peru on June 3 to help the Andean nation tackle the coronavirus pandemic. That same day, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo announced another tightening of the sanctions screws. This time he targeted seven Cuban entities, including Fincimex, one of the principal financial institutions handling remittances to the country. Also targeted was Marriott International, which was ordered to cease operations in Cuba, and other companies in the tourism sector, an industry that constitutes 10 percent of Cuba’s GDP and has been devastated globally by the pandemic.

It seems that the more Cuba helps the world, the more it gets hammered by the Trump administration. While Cuba has endured a U.S. embargo for nearly 60 years, Trump has revved up the stakes with a “maximum pressure” strategy that includes more than 90 economic measures placed against the nation since January 2019. Josefina Vidal, Cuba’s ambassador to Canada, called the measures “unprecedented in their level of aggression and scope” and designed to “deprive the country of income for the development of the economy.” Since its inception, the embargo has cost Cuba well over $130 billion dollars, according to a 2018 estimate. In 2018-2019 alone, the economic impact was $4 billion, a figure that does not include the impact of a June 2019 Trump administration travel ban aimed at harming the tourist industry.

While the embargo is supposed to have humanitarian exemptions, the health sector has not been spared. Cuba is known worldwide for its universal public healthcare system, but the embargo has led to shortages of medicines and medical supplies, particularly for patients with AIDS and cancer. Doctors at Cuba’s National Institute of Oncology have had to amputate the lower limbs of children with cancer because the American companies that have a monopoly on the technology can’t sell it to Cuba. In the midst of the pandemic, the U.S. blocked a donation of facemasks and COVID-19 diagnostic kits from Chinese billionaire Jack Ma.

Not content to sabotage Cuba’s domestic health sector, the Trump administration has been attacking Cuba’s international medical assistance, from the teams fighting coronavirus today to those who have travelled all over the world since the 1960’s providing services to underserved communities in 164 countries. The U.S. goal is to cut the island’s income now that the provision of these services has surpassed tourism as Cuba’s number one source of revenue. Labeling these volunteer medical teams “victims of human trafficking” because part of their salaries goes to pay for Cuba’s healthcare system, the Trump administration convinced Ecuador, Bolivia and Brazil to end their cooperation agreements with Cuban doctors. Pompeo then applauded the leaders of these countries for refusing “to turn a blind eye” to Cuba’s alleged abuses. The triumphalism was short lived: a month after that quote, the Bolsonaro government in Brazil begged Cuba to resend its doctors amid the pandemic. U.S. allies all over the world, including in Qatar, Kuwait, South Africa, Italy, Honduras and Peru have gratefully accepted this Cuban aid. So great is the admiration for Cuban doctors that a global campaign has sprung up to award them the Nobel Peace Prize.

The Trump administration is not just libelling doctors, but the whole country. In May, the State Department named Cuba as one of five countries “not cooperating fully” in U.S. counterterrorism efforts. The main pretext was the nation’s hosting of members of Colombia’s National Liberation Army (ELN). Yet even the State Department’s own press release notes that ELN members are in Cuba as a result of “peace negotiation protocols.” Cuban Foreign Minister Bruno Rodríguez called the charges dishonest and “facilitated by the ungrateful attitude of the Colombian government” that broke off talks with the ELN in 2019. It should also be noted that Ecuador was the original host of the ELN-Colombia talks, but Cuba was asked to step in after the Moreno government abdicated its responsibilities in 2018.

The classification of Cuba as “not cooperating” with counterterrorism could lead to Cuba being placed on the U.S. State Sponsors of Terrorism list, which carries tougher penalties. This idea was floated by a senior Trump administration official to Reuters last month. Cuba had been on this list from 1982 to 2015, despite that fact that, according to former State Department official Jason Blazakis, “it was legally determined that Cuba was not actively engaged in violence that could be defined as terrorism under any credible definition of the word.”

Of course, the United States is in no position to claim that other countries do not cooperate in counterterrorism. For years, the U.S. harbored Luis Posada Carriles, mastermind of the bombing of a Cuban civilian airplane in 1976 that killed 73 people. More recently, the U.S. has yet to even comment on the April 30 attack on the Cuban Embassy in Washington D.C., when a man fired on the building with an automatic rifle.

While there are certainly right-wing ideologues like Secretary Pompeo and Senator Rubio orchestrating Trump’s maximum pressure campaign, for Trump himself, Cuba is all about the U.S. elections. His hard line against the tiny island nation may have helped swing the Florida gubernatorial campaign during the midterm elections, yet it’s not clear that this will serve him well in a presidential year. According to conventional wisdom and polls, younger Cuban-Americans – who like most young people, don’t tend to vote in midterms – are increasingly skeptical of the U.S. embargo, and overall, Cuba isn’t the overriding issue for Cuban-Americans. Trump won the Cuban-American vote in 2016, but Hillary Clinton took between 41 and 47% percent of that electorate, significantly higher than any Democrat in decades.

As an electoral strategy, these are signs that Trump’s aggression towards Cuba may not pay off. Of course, the strategy might not be just about votes but also about financing and ensuring that the Cuban-American political machinery is firmly behind Trump.