#ancient egyptian papyrus

Video

youtube

Ancient Egyptian Papyrus Making - A Documentary on Ancient Writing Systems

#youtube#egyptian papyrus#papyrus#papyrus making#ancient egyptian papyrus#writing systems#ancient writing systems

0 notes

Text

A satirical papyrus showing a lady mouse being served wine by a cat while another cat dresses her hair, a third cares for her baby, and a fourth fans her. The mice have hilarious huge, round ears.

Where: Egyptian Museum Cairo

When: New Kingdom

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

A female mummy encased in a cartonnage

from tombs found at Taposiris Magna,

modern day Abusir, Egypt

Cartonnage is the term used in Egyptology and Papyrology naming a method used in funerary processes to produce cases, masks, or panels to help cover all/part of mummified or wrapped bodies

#art#archaeology#mummy#egypt#ancient art#ancient egypt#egyptology#ancient culture#ancient kemet#kemetic#kemet#egyptian art#papyrus#papyrology#cartonnage#mummification#mummified

459 notes

·

View notes

Text

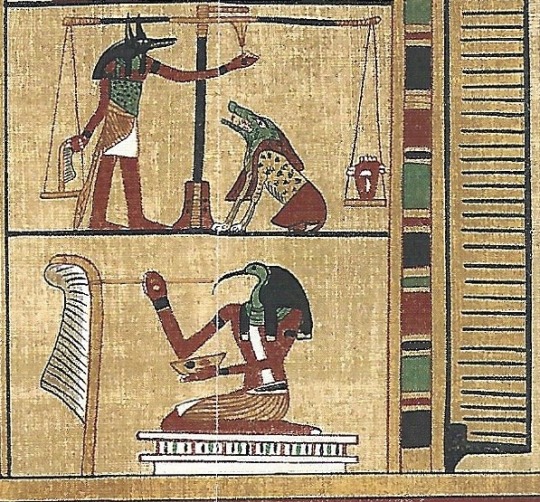

Everybody please look at these two drawings of Anubis and Ammut and of Thoth painting a feather from The Papyrus of Ani.

#The book of the dead#The papyrus of Ani#egyptian mythology#egyptian gods#Thoth#anubis#ammut the devourer#Ammit the devourer#Anpu#Inpu#ancient egypt stuff#no id#undescribed#Djehuty

381 notes

·

View notes

Text

Discover how wasabi is revolutionizing the preservation of ancient texts. A groundbreaking study reveals its unexpected effects.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

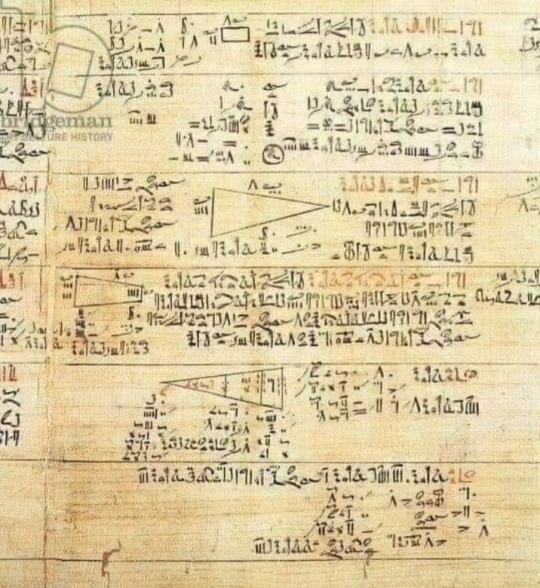

Papyrus of Ahmose or Mathematical Rhind (1500 BC / 1550 BC) is the oldest manuscript written in Algebra and Trigonometry.

Manuscript shows that Egyptians used first-order equations and solved them in several ways.

They know quadratic equations and solve them. They also know numerical and geometric sequences and know quadratic equations like two :

X2 + y2 = 100,

Y = 3/4 x, where x = 8, y = 6,

This equation is the origin of Pythagoras theorem, a2 = b 2 + c 2, and Egyptians used to call unknown number (koom).

Pythagoras developed his mathematical theories after travelling to Egypt and learning from Egyptian priests.

This has been proven in books of Greek historians and scholars such as Farpharius of Sour, Herodotus, and Thales.

Egyptians had Algebra, Trigonometry, and Geometry about 2000 years before the birth of Pythagoras and about 3000 years prior to al-Khwarizmi being born.

—

The Rhind Mathematical Papyrus (RMP; also designated as papyrus British Museum 10057 and pBM 10058) is one of the best known examples of ancient Egyptian mathematics.

It is named after Alexander Henry Rhind, a Scottish antiquarian, who purchased the papyrus in 1858 in Luxor, Egypt.

It was apparently found during illegal excavations in or near the Ramesseum. It dates to around 1550 BC.

#Papyrus of Ahmose#Mathematical Rhind#Rhind Mathematical Papyrus#manuscript#Pythagoras#Pythagoras Theorem#Ancient Egyptian Mathematics#Ancient Egypt#Alexander Henry Rhind#papyrus#Achaeo Histories#algebra#geometry#mathematics#Ahmes#Ahmose#Egyptian civilization#Trigonometry#mathematical theories#Hieroglyphs#Ramesseum

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

A very informative text of neurosurgeon and historian of science Pr. Alexander Brawanski on the Edwin Smith Papyrus and more generally on ancient Egyptian medicine - II

"Treatment concepts, magic, and science

The ancient physicians had a specific and rather sophisticated pathophysiological concept of (internal) diseases [33], which unfortunately complies with little of the actual inner workings of the body as we understand them today. They assumed some type of circulatory system, which included the heart and in which bad substances could accumulate and circulate. Furthermore, an elaborated materia medica was available with sophisticated application methods. Some of the applied drugs were effective [34–36]. This knowledge was acquired over the centuries by trial and error and finally led to the high esteem of the medical profession in the ancient world [37]. Part of this knowledge has survived in several larger medical papyri and many fragments [18], a textual corpus of which the ESP constitutes only a minor fraction.

As has often been observed by students, the anatomical descriptions in the ESP are clear, descriptive, and sometimes unique. One of the classics is the comparison of the surface of the (injured) brain to molten copper (case 6). However, the general anatomical knowledge was limited; sometimes it is nicknamed “kitchen” or slaughterhouse anatomy [38] because much of the information seems to be derived from the slaughterhouse indeed. An example is the uterus, which is represented hieroglyphically as the uterus bicornutus, which is not present in human beings. In this context, the question is unresolved as to whether at the time of the ESP the embalmers’ knowledge was used by physicians and whether they were two strictly separated professions. According to Ghalioungui, there were individuals bearing the title of physician who very likely could have been embalmers as well [25]. In the later period of Egyptian history, the Egyptian title for physician could mean both. Some information that is presented in the ESP related to spinal injuries does suggest, however, that there must have been an exchange of information between these groups [7]. Otherwise, some descriptions of spinal injuries in the ESP could not be described in such detail.

Besides all this, the ancient Egyptian physicians firmly believed in supernatural forces such as demons, undead persons (Widergänger), and divine influences as causes of illnesses and consequently treated them by magicical rituals. The less obvious the cause of a disease, the more common was magic [39, 40]! Magic and practical medicine were not different or contradictory to physicians. This differentiation is artificial and was introduced by modern medical historians [41]. The ancients often used magical spells to enhance the effectivity of medical applications, and often magic alone. Thus, there is a significant number of magical spells in other important medical papyri [42]. All this is not so necessary in the ESP, as the causes of the wounds and the injuries are well known, thus showing the “rational” approach, which exemplifies the strength of these ancient societies: The collection of information and facts and the classification of this information. This complies with the “organizational principle” that ruled these societies and without which they could not exist or survive. The ancient Egyptians had available lists of birds, countries, and even objects of daily life [43]. They used them for reference and education. The major intent of these lists was to classify and thus structure the world in order to cope with it. Knowledge meant power. Therefore, the knowledge of the physicians often was called “secret” and was not available to everyone, provided he could read at all.

This classification principle is perfectly exemplified in the ESP. The single cases are arranged from the top to bottom of the body. This may seem natural per se, but this structural principle again had a religious background. We know of litanies of Gliedervergottung (deification of members of the body) [44, 45] that have the same order. Here we come to another important point, namely that medicine was deeply rooted in the divine realm. The relevant documents were stored in the temples; education as well as treatment took place there. Some of the physicians may have been priests as well, and a specific type of priest also could magically treat patients [46] to some extent. All this explains why magic was a firm component of medical practice. Specifically in prescriptions with magic components, patients were often addressed as and equated with the god Horus, who was helped by his mother Isis.

In this context, we come to the major driving force of ancient Egyptian thought. All (official) activities had to follow one major principle that traverses all ancient Egyptian behavior: the universal order of the world—“Maat”—which kept the world running. It had to be preserved by all means because it was threatened every day. This fact sets Egyptian medicine in the proper position and environment in this society. According to Egyptian belief, ancient “objects” with a long tradition underpinned the validity of this concept. Thus, we can find the statement in medical texts “that the text is a copy of an ancient papyrus found in a chest by chance” [47] and thus must be qualitatively good, because otherwise it would have perished. Ancient Egyptian society wanted stability and no abrupt changes. This can be seen very well in ancient Egyptian art, which did not change in its basic principles throughout the existence of ancient Egypt. Once a reasonable solution to a problem was achieved, it was preserved, and one did not necessarily look for other solutions. This complies well with the ESP, which was copied around 1600 BCE, but stems from a much older document according to the language of this papyrus [1].

This does not mean that there was no progress at all or that no variety of approaches existed. In the medical literature, there are significant variants in the selection and applications of drugs [40]. Even foreign treatments were accepted in the medical canon [42, 48, 49]. However, over time there was little obvious significant change. Due to this general attitude of ancient Egyptian society and due to the close connection of medicine to the divine, science in the modern sense was not possible and possibly not even thought of. One did not experiment with religious issues and endanger the general world order. The ancient Greeks were the first to question the divine influence on diseases in the seventh century BCE. Obviously this society was open to these questions [50]. However, even at the time when Hippocrates was active, the Asclepiads still recommended treatment in the temples and help from the gods [51].

The individual patient

Now the fate of the individual patient should be examined in reference to the cases described in the ESP.

One of the major issues seems to have been to establish a proper prognosis that determined the further procedures. This may sound astonishing at first. However, it is understandable when we regard this from the viewpoint of a major organization. This was nothing other than triage, which makes even more sense in the context of limited treatment options (see below). The verdict/prognosis was written in red in the ESP, which underlines its importance. This method is not unusual as we can still find this approach in ancient Greek medicine (1,000 years later). Here the major issue was also determining the prognosis [52]. Actually, the authority and credibility of an ancient Greek physician depended to a large extent on establishing a fast and proper prognosis [53].

It is important to note that the Egyptian physicians did not give a single disease name in the ESP, but an enumeration of symptoms. This is a relevant fact, as a “single-word” diagnosis usually implies a coherent pathophysiological concept that each physician understands. Thus, for modern physicians the concept of diabetes includes various aspects that do not have to be enumerated each time. However, a loose collection of symptoms rather constitutes a syndrome, in the best medical sense, which does not necessarily imply an understanding of the underlying pathophysiology. We would for instance summarize some of the injuries in the ESP (e.g., cases 18–20) as cranial base fractures. To any modern physician, this term would mean a specific injury with variable severity depending on the location and strength of the impact. Thus, a physician would rather summarize the single cases under one heading. Similarly, the last case (case 48) in the ESP deals with lower back pain. Several symptoms are enumerated. From a modern point of view, this could indicate several diagnoses, such as a tumor, a slipped disc, or a simple joint problem. The ancient Egyptian physician gave a “syndromatic” description from which a final modern diagnosis can hardly be developed, as relevant information is missing. Thus, often a definitive modern diagnosis cannot be made simply because of the lack of specific information in the ESP. This is not a denigration of the ancient Egyptian medical art, which was quite sophisticated despite their limited knowledge, but we have to know what we can take for granted.

In addition, we have to be clear that the treatment options in the ESP are very limited. Most of them are supportive in the best sense, but hardly any of them are curative. One exception may be the readjustment of a dislocated jaw (case 25). The same holds true to some extent for the relocation of a broken collarbone (cases 34–35). Here, the outer contour is readjusted; however, the fracture is still there with all its implications for malfunctioning of the adjacent joint (shoulder). Besides this, some treatment suggestions are clearly detrimental to the patient. In case 28, an injury of the esophagus is obviously described. The physician recommended a closure of the superficial wound without further inspection of the deeper layers of the injury. This patient would definitely die from the sequelae of a mediastinitis, which is still a severe disease today. One may muse about the fact that the physician recommended a superficial closure of the wound in this case. Clearly the outflow of water should be mended. The guiding principle was obviously the restoration of the integrity of the outer aspects of the body. This corresponds well to the practice of mummification. Again the outer appearance of the mummy was important for the afterlife, but not so much the internal organs, which were removed during mummification and put in canopic jars separately.

Thus, the fate of the patient was actually determined by the seriousness of the injury, the severity of the following infection, and the physical strength of the patient to cope with these. The main intent of the ancient Egyptian physician was to establish a prognosis. We must be clear about the fact that a negative prognosis meant that the patient was left alone. What this may have looked like is described more fully in the Hippocratic Epidemics. I quote Epidemics 7,32 in reference to the ESP, case 22: “On a Macedonian: …he was struck over the left temple, a superficial wound. He fainted after the hit and fell. On the third day he was speechless. He tossed about. Fever was not very intense…. He heard nothing and was not conscious, nor was he still. Moisture was around his forehead and beneath the nose to the chin. He died on the fifth day” [54]. It is interesting to note that these observations, which are of importance to the physician, are not mentioned in the ESP. This is simply due to the fact that “bad” things could and should not be written down. The Egyptians believed in the supernatural strength of their script; it was not understood as a mere transporter of information. Describing bad events would disturb Maat, the general word order.

Conclusion

What is the best way to approach the ESP? It is rooted in a complex environment, which has to be taken into account in order to appreciate this document fully. Magic definitely was an elementary part of ancient Egyptian medical practice and was applied at various occasions. This approach to cope with problems does not limit the overall achievements of this ancient society. Does the ESP contain science? That depends on the definition and is difficult to grasp [55]. If one applies the “modern” idea of science representing the objective truth, the answer would be no. However, respecting the specific principles to define natural events and mechanisms, which each of these ancient societies used, I would say—in a basic sense—“yes.” However, a simple “close reading” of the ESP, including one to apply modern concepts and diagnoses [56], will most likely not do justice to this unique document."

Professor Alexander Brawanski, University Hospital Regensburg, Germany

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bring back Papyrus paper that way we can all write like a Egyptian!🇪🇬

📜🖋️

#history#papyrus#egypt#writing#paper#ancient history#plants#ancient egypt#ancient greece#ancient rome#writing history#medieval europe#new kingdom#art#old kingdom#parchment paper#egyptian history#nile river#islamic golden age#roman empire#scrolls#egyptology#medieval history#mediterranean#ancient writing#ptolemaic egypt#nickys facts

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

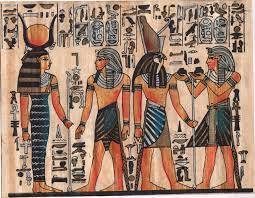

Egyptian Papyrus Painting: A Journey Through an Ancient Art Form of Timeless Beauty

Today, we continue our trek around the world looking at art forms we may not be familiar with. We have talked about Mexican Folk Art, Street Art, Chinese Kites, Japanese Origami, Sand drawings of Vanuatu, and Kintsugi so far. Now we go way back centuries to look at and learn about an ancient art form that is very much alive today. The art of the Egyptian Paypyrus Painting is both interesting…

View On WordPress

#Ancient Art#Ancient Civilizations#Art Collectors#Artistic Techniques#Book of the Dead#Cultural Heritage#Egyptian Gods#Egyptian Mythology#Egyptian Papyrus Painting#Egyptian Symbolism#Hieroglyphics#Historical Art#Isis#Mineral Pigments#Nile River#Osiris#Papyrus Artwork#Pharaohs#Sun God Ra#Traditional Art Forms

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

LOOK AT THE PAINTING I GOT FROM COMIC CON!!! ITS MADE OUT OF REAL PAPYRUS AHHHHH— unfortunately it’s been taking forever to find a frame that fits right :(

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

fav cannes 2022 red carpet looksss

#other than bella hadids cos i always think she looks amazing n deserves her own post#deepika padukone looks like an ancient egyptian papyrus scroll idk why but i love it#cannes film festival#fashion

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

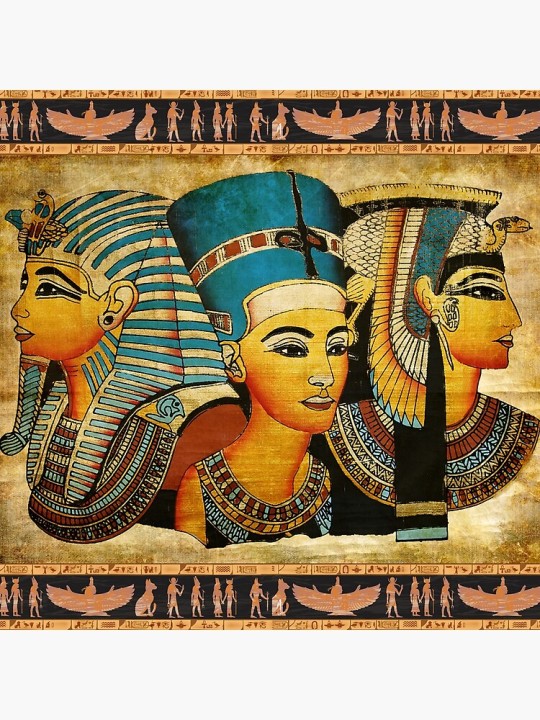

Goddess Egypt Papyrus Painting Floor Pillow

#egypt#goddess#egypt gods#papyrus egypt egypt paint civilization lovely nefertiti cleopatra egypt ancient ancient egypt egyptian hieroglyph mummy antiquity anubis cai

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The papyrus of Tjanefer. Thoth and the mouse-headed god, who wears a single maat-feather, hold the deceased's hands as the lead him to Osiris. They're followed by Hepet-Hor, who has lioness- and crocodile-faces, wears a white crown, and holds a pair of knives. The Devourer stands with her front paws on the base of Osiris' throne like a pet who wants a treat; I think this is a way of quickly summarising the judgement scene. Behind Osiris is a lion-headed god with two wriggly snakes coming out of his head. (Anyone who can read the hieroglyphs over the Devourer's head will have my eternal gratitude.)

When: Third Intermediate Period, 21st Dynasty

Where: Egyptian Museum, Cairo

#Ancient Egypt#papyrus#Amduat#Hepet Hor#Osiris#Thoth#mouse god#The Devourer#Third Intermediate Period#21st Dynasty#Egyptian Museum Cairo#Tjanefer

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

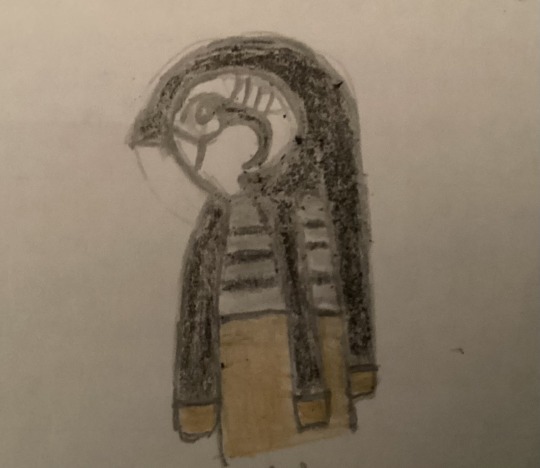

I tried recreating what Ra looks like in this absolutely adorable illustration from the Ani papyrus

#egyptian mythology#egyptian gods#ra#Interesting detail with this illustration is that the ‘insides’ of his eyes are white not yellow#I’m not sure it’s supposed to be the inside since some real falcons have completely black eyes with yellow colouring on the head around the#But in the Egyptian art itself falcon headed gods often end up looking like they have black pupils/irises and yellow scleras#ancient egypt stuff#Ava makes art#The papyrus of ani#The book of the dead

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

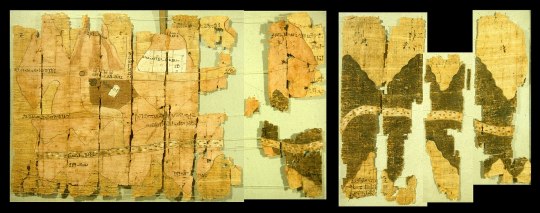

The Turin Papyrus Map: The Oldest Surviving African Map Of Topographical Interest From The Ancient world

The Turin Papyrus Map stands as an extraordinary artifact, offering a captivating glimpse into the ancient world through its detailed topographical and geological features. Originating from around 1150 BCE, the map was crafted by the renowned Scribe-of-the-Tomb Amennakhte, son of Ipuy, for Ramesses IV’s ambitious quarrying mission in the Eastern Desert. Measuring 2.8 meters in length and 0.41…

View On WordPress

#African History#Ancient Egyptians#ancient egyptians history#Nubian Shield#Ramesses VI#The Turin Papyrus Map#Turin Papyrus Map#Wadi Hammamat

0 notes