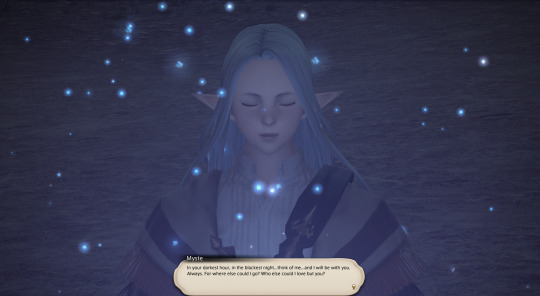

#also. this one line and the line of murky from patho prove once and for all that my one great weakness are video game children

Text

;_;

#physically sitting at my desk mentally recreating the lie down try not to cry cry a lit meme#aaaaaaAAAAAAAAA I AM NOT OK! THIS QUESTLINE HURT ME#ok incomprehensible emotional screaming aside I'm just. gods these are such good quests#i understan why everyone's been praising them so much now#love the writing. love how it humanizes the WoL. love how every conclusion to the quest was gut wrenching yet still left you hopeful#can't wait to brainstorm the ways to implement it in Nigen's story and think of how she feels about it all too#also. this one line and the line of murky from patho prove once and for all that my one great weakness are video game children#telling me they love me#... and now that y'all know it I have to kill you before you use it against me#matry plays ffxiv

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Compilation of Various Changeling Headcanons of Mine

Been a while since I last wrote a massive list of hc's I have for a character, but I've been feeling bad for the lack of Patho content I’ve been sharing and want an excuse to talk about our beloved Clara the Changeling 🐀✨

Some spoilers for two of Pathologic Classic's endings are included in these, I should mention. Otherwise, enjoy!

Clara is a demisexual lesbian. I don’t need to do an in-depth detailed analysis to prove it, I just… know it!

She’s also neurodivergent, but in a way that makes it hard to give her a proper diagnosis. Really it’s most likely that she has overlapping disorders (adhd, bpd, autism) mixed in with others exclusive to those who’ve spawned from the Earth.

I’ve discussed this in another post once, but Clara’s biggest fear is her own body. A combination of knowing she was born from the clay and bones of the Earth combined with the truth about the world itself has given her a dreadful insight on how fundamentally different her physiology is from the other humans in the Town. Oftentimes she’ll feel different textures than what her skin and hair is supposed to feel like, and will need to stop what she’s doing and convince her mind that she’s real before the right textures return to her senses.

Is a tactile learner, and often prefers to show affection via touch (ex: patting one on the shoulder/back, holding hands, hugging, etc.)

The stress of her journey made her shed many tears, but now she’s become embarrassed about it. She’ll do everything in her power not to cry in front of others if she’s ever upset, simply saving it until she’s buried herself under some bed sheets or finds a lonely alley to cry her sorrows away.

That being said, if someone she cares about did find her sobbing and wanted to comfort her, she would throw herself into their arms and take in their compassion like a flea to fresh blood!

Clara was born with an innate understanding for very adult concepts and philosophies despite having the body and mind of a teenager. However, she finds herself preferring the conversations she has with the Town’s kids compared to the adults.

For example, with Sticky and Murky she can assuredly engage in a long, thoughtful debate on the mystical qualities and immaterial essence of life held within some nuts they found lying the dirt, while with the Bachelor and Haruspex she needed to slowly and carefully explain to them why it’s wrong for adult men their age to bully a teenage girl.

I have many complex feelings on her bond with Alexander Block, but I do believe that after her meeting with The Powers That Be she chooses not to accompany Block on the front lines. Even if she wants to leave, she knows more than anyone that this world only exists within the confines of its setting, and thus she can only live within the space created for her and the others. Perhaps Block can leave, but just as she says to him in her ending, "You came out of thin air and you'll pass into nothingness."

She still sees the Albino as her brother, and will often times travel deep into the steppe to visit him.

Once the plague is quelled Clara eventually begins to form a new family unit by being communally raised; essentially moving about at her own leisure between the residences of the members of her bound most patient with her (Yulia, Rubin, Lara, and even Bad Grief on some occasions) as well as Daniil and Artemy, who are both willing to put their past quarreling behind them. Presuming the Termite Ending was picked, of course!

The Saburovs remain unwilling to accept the future granted to the Termites, and Katarina in particular still believes that Clara is her proper heir and has tried to reach out and bring her back into their care to start over. She avoids them like the plague, still not ready to forgive them for abandoning her.

If the Humble Ending was picked, then she lives all by herself in the Rod, with only the consistent company of her two surviving humbles and the Bachelor and Haruspex; the three having ended their feuding after learning the shared knowledge of being dolls, yet still haven't fully recovered from the trauma of it all. She sends letters to Commander Block hoping to hear about what the outside world is truly like, even if all he can tell her are what battles lay on the front lines, and is trying to defy her fated rivalry against Maria and Capella by trying to form an alliance, perhaps even a friendship, with them to ensure a good future for the Town.

Capella is the only one willing to tolerate her presence at the moment, yet is still uneasy about this new future the Changeling has created…

While Clara always preaches about her fierce understanding of the divine powers of love, she genuinely does not understand the concept of being loved herself. Thanks to her hasty upbringing in a cult, she assumes that it is something like a commodity: needing to be earned by successfully completing tasks, and being instantly lost if she fails said tasks. The reason her mood nosedives into dramatic self-loathing whenever she angers/fails the people she cares about is because she believes that they now no longer love her as much as they used to.

Okay those last few points were pretty depressing, let me lighten it up a bit. Clara and Grace often have fun sleepovers in the cemetery together! Or at least what weird teenage girls closely connected to death find fun, like communicating with the dead and expressing their feelings toward one another in a series of flowery, cryptic riddles :)

I can totally see her owning pet rats! They’ll cling to her scarf and ride her like a taxi as she walks throughout town, freaking out every adult she passes.

Going back once more to her complex feelings about her own body, Clara also feels just as strange about her gender. She knows her anatomy isn’t built the same way “normal” girls’ are, despite taking the form of one. Often she feared that those who knew of her unnatural birth secretly saw her as an inhuman monstrosity, let alone those who haven’t found out yet. But eventually, with the support of those closest to her, she learns that humans inherently do not fit into the neat, fantastical boxes of cis heteronormalcy and slowly embraces her unique form of girlhood, and perhaps may start experimenting with using other pronouns too.

#clara the changeling#pathologic#pathologic headcanons#if anything this came about to hype myself up for a clara centric fic I’m writing#but it has been a while since I posted a massive hc list#I need to get back into the habit of that

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hyperallergic: Arcade Fire Gives Up on Life

To learn how crushingly the new Arcade Fire album has disappointed fans, critics, and providers of online content, one need only glance at their Metacritic page. To fully comprehend why requires several listens, each more dumbfounding than the last. Anyone who associates the band with uplift will find the new Everything Now, out since July, an enervating thing: a sniveling black hole of negativity, littered with ostensible protest songs aiming to critique societal problems from a soapbox ten million miles above their fanbase. “Infinite Content,” for example, jolts over a straightforward punkish beat as lead rock hero Win Butler repeats the same line over and over: “Infinite content/infinite content/we’re infinitely content.” Get it? “Content” meaning posts on social media, but he’s making a pun on “content” the adjective! He’s calling out the emptiness of our technology-addicted lives! He doesn’t think we’re infinitely content at all–he thinks the internet lulls us into a false sense of security! The next song, a slower, sweeter country-tinged jangler, is also called “Infinite_Content”, with the same exact lyric, except they’ve added an underscore to the title. Get it? Computers!

These songs baffle the critical faculties. To state point blank that “Infinite Content” and “Infinite_Content” aren’t clever is to belabor the self-evident. Likewise, calling Everything Now a failed stab at profundity feels as productive as feigning shock that the current president said something vile and semiliterate in the media yesterday. How exactly the band wound up here is the relevant question.

I won’t mimic the consensus and call Arcade Fire a great band undone by sanctimony when they’ve been bombastic and heavy-handed since day one. Since their beloved debut, Funeral (2004), they’ve specialized in spacious, grandly beautiful rock anthems, undercut by specific deflationary moments of bathos that could easily have been excised. Funeral’s “Wake Up,” widely considered their greatest and most moving song, soars over rhythmic power chords, acoustic classical instruments from violin to accordion, and a massive, wordless football chant of a chorus. The effect rouses — right up to when Butler, pumping his figurative fist, ends a verse by screaming “I guess we’ll just have to adjuuuuuuuust” as if expecting cheers from all the young adults in the audience who’ve felt growing pains, whereupon the mushy qualifiers (“I guess”) and the weak verb (“adjust”) collapse under the weight of the anthemic moment. Often they powered through anyway. Their second album, the scary, deeply felt Neon Bible (2007), infamously recorded in an abandoned church, uses the consequently murky sound to simulate a humming, ominous “Ocean of Noise.” Guitars and pianos and booming organ and, by metaphorical extension, the entire world, all crash down apocalyptically around them, lending physical reality to the political urgency of their songwriting. The Suburbs (2010), a relaxed, rhapsodic variant on the same classically textured arena-rock blend, is pretty enough, at least to compensate for an overlong running time and the band’s labored attempt to make a definitive statement on maturity, adolescence, and the decline of tradition in the modern world. But ever since Pitchfork anointed them voices of a generation — articulating the existential anxieties of kids who grow up, move to the city, and struggle with adulthood and their place on the traditionalism/modernity axis — they’ve always felt the weight of the world more heavily on their shoulders than any band deserves or should presume. Condescending social commentary by a large, communitarian band of Canadian art-rockers will inspire nobody in 2017. Music that once swept and thundered has turned tighter, harsher, and more unpleasant. Songwriting that once voiced progressive resolution now howls with conservative despair.

To students of rock history, Everything Now and its predecessor, Reflektor (2013), will sound awfully familiar: didn’t U2 already make these albums in the ‘90s? Arcade Fire’s career arc resembles U2’s exactly: insufferably earnest arena-rock band starts out sincere, anthemic, grandiose before tiring of their own reputation and deciding to embrace electronics, irony, and such. My, how history repeats itself. It must embarrass fans across the global indie-rock community that U2 did it better; few bands anywhere have matched the sonically warped, chemically tainted, wacky garish neon fury of “The Fly” and “Staring at the Sun.” Reflektor and Everything Now, meanwhile, stand as definitive proof that those who don’t know what irony is shouldn’t dabble in it. While rock-conventional song structures still dominate, both records abound with glittery synthesizer, honking horns, jaggedy postpunk beats, dancier tempos and textures, really, anything to prove they’re not some stodgy old rock band, they’re cool. They display no aesthetic commitment to these musical usages themselves, flaunting them instead as tokens of edge, an association that works only when being a stodgy old rock band is the backdrop.

Despite many flatfooted attempts at disco and the unfortunate choice to follow a song called “Hey Eurydice” with “Hey Orpheus,” Reflektor occasionally sparkles, primarily on the soaring guitars of “Normal Person” and the xylophone-backed nursery rhymes of “Here Comes the Night Time.” On Everything Now the musical blend curdles utterly. The glowing keyboards, dinky flutes, angry rhythm guitar parts, assembled sound effects, and the like are incorporated poorly, failing to mesh with the grander rock structures that subsume them, sticking out like otiose clip-on accessories. The resulting music is awkward, pinched, and ugly. “Signs of Life,” whose death-march bassline is repeated exactly by an abrasive horn section, epitomizes a cramped strain that is now the band’s operative mode. “Creature Comfort” is perhaps definitive: the song’s cheerfully affectless guitar riff plus synth squelch, combined with Butler’s declamatory talk-singing, aim to evoke classic dancepop, New Order’s “Temptation” maybe. The talk-singing more closely resembles an eager parody of a) white singers trying to sound rhythmically astute; b) Bono’s vocal delivery on “Hawkmoon 269”; c) Arcade Fire’s prior output.

That’s to say nothing of the lyrics. “Creature Comfort” is an anti-suicide plea ambiguous enough not to specify whether the band’s own “first record” saved a fan from suicide or drove her to it. There’s no empathy; the person in question is treated like a cautionary tale to wring one’s hands over. I count two songs on Everything Now that haven’t completely given up on life: “Peter Pan,” whose plinked keyboards and funkoid bassline are sparse enough to let the song’s emotion breathe, and the penultimate “We Don’t Deserve Love,” whose climactic descending guitar hook suits both the queasy synth noodling in the verse and the quiet pathos of a romantic anthem that, after an album’s worth of vitriol, aims to establish love as humanity’s redeeming factor. As for the vitriol, it’s disheartening. Once they wrote compassionately and from experience, especially on The Suburbs; their grand proclamations about alienation and adulthood were delivered by narrators implied to have lived through such processes. The songs on Everything Now diagnose the evils of millennials — kids these days! — from the voice of an older man who knows everything. Few things are more tedious than a band lecturing their fanbase on the fanbase’s moral failings and the necessity for everyone to act more like the band. Which song is the most insulting, you ask? Is it the title track, whose blandly suburban mall keyboards accompany a rant against information overload and the media-literate? Is it “Chemistry,” a rhythmically wooden reggae-inflected blues-rocker that lists cliched pickup lines as if revealing something deep and horrifying about gender relations? I vote for “Signs of Life,” a lament for the supposedly repetitious, joyless ritual that is party culture: “Spend your life waiting in line/you find it hard to define/but you do it every time/then you do it again/looking for signs of life/looking for signs every night/but there’s no signs of life/so we do it again.”

Ah — the futility of hedonism! The misery of affluence! Cool kids who pretend to have fun because everyone else does, but secretly feel empty inside! Where have we heard this before? From Halsey, from Lorde, from Frank Ocean, from Drake, from the Weeknd, from the fucking Chainsmokers. With Everything Now, Arcade Fire joins the vast litany of artists who’ve taken it upon themselves to explain Why Modern Kids Suffer and Why Millennials are Ruining Society. That they exempt themselves from their social critique, unlike the aforementioned artists, proves only that exclusionary indie elitism is alive and well. Listening to Neon Bible in the wake of Everything Now perturbs; one wonders if their urge to hide under the covers from the “ocean of violence” outside really targeted Bush, or if the chaotic entanglements of modern life just offended their regressive notions of purity. Their earlier albums surged with positive energy, while Everything Now is the bad album that previous good albums made inevitable. A collapse from idealism into cynicism should surprise nobody. Those who believe in false if rousing ideals can inspire, as Arcade Fire has in the past, and that they’ve gradually become bitter over 13 years after being disappointed in such ideals doesn’t mean they no longer believe in them. On the contrary, they hate the world for not living up to how it should be. Idealism, cynicism, these are not opposites — it just depends on whether the sentimental idiot in question is in a good or bad mood.

Tellingly, their famously energetic live show transcends the negativity of the record. Playing to a festival crowd at Lollapalooza this year, they jumped around, traded instruments, conjured uplift from despair, and generally made joyous, triumphant, cathartic noise. Behold — a welcome sign that they still believe in humanity. I hope their next album, also, yields such evidence.

Everything Now (2017) and Reflektor (2015) are available from Amazon and other online retailers.

The post Arcade Fire Gives Up on Life appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2fTDgmM

via IFTTT

0 notes