#U.S India Dialogue

Text

U.S. WARNS CHINA ON TAIWAN AS DEFENSE OFFICIALS MEET TO COOL TENSIONS

SINGAPORE — U.S Defense Secretary Lloyd J. Austin III warned China on Saturday against what he called “provocative and destabilizing” activity near the disputed island of Taiwan, following talks with China’s defense minister, Gen. Wei Fenghe, that focused on preventing regional tensions from escalating into crises.Taiwan — a self-ruled island that Beijing claims as its own — was one of the topics…

View On WordPress

#China#China’s defense minister#Gen. Wei Fenghe#India#Japan#Mr. Austin III#President Joe Biden#President Xi#Russia&039;s invasion of Ukraine#Shangri-La Dialogue#Singapore#Taiwan#Taiwan President Tsai Ing-Wen#U.S Defense Secretary Lloyd J. Austin III#Washington DC

0 notes

Text

With a history of short-term governments in Nepal’s 15 years of democratic progression, the current reconfiguration is no surprise, and it will be no surprise if the Maoists get back again with the Nepali Congress in months and years to come.

Power sharing, political discontent, ideological differences, underperformance, and pressure to restore Nepal to a Hindu state – a long list of reasons reportedly forced the Maoists to sever ties with the Nepali Congress. While the Nepali Congress expected the Maoist leader and current prime minister, Pushpa Kamal Dahal (also known by his nom de guerre, Prachanda) to leave the alliance, it did not expect an overnight turnaround. [...]

Dahal reportedly conveyed to the Nepali Congress chair, former Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba, that external pressure forced him to join hands with CPN-UML and form a new government.

If this assertion is true, China emerges as a plausible factor, given its historical inclination toward forging alliances with leftist parties in Nepal. This notion gains credence in light of China’s past efforts, such as its unsuccessful attempt in 2020 to mediate the conflict between Oli and Dahal.

On the other hand, India has enjoyed a comfortable working relationship with the Nepali Congress and the Maoists. Although Maoists were a challenging party for New Delhi to get along with when Dahal first gained the prime minister’s seat in 2008, the two have come a long way in working together. However, the CPN-UML has advocated closer ties with the northern neighbor China; Beijing suits both their ideological requirements and their ultra-nationalistic outlook – which is primarily anti-India. [...]

India faces challenges in aligning with the Left Alliance for two key reasons. First, the energy trade between Nepal and India has grown crucial over the past couple of years. However, India strictly purchases power generated through its own investments in Nepal, refusing any power produced with Chinese involvement. With the CPN-UML now in government, Nepal may seek alterations in this arrangement despite the benefits of power trade in reducing its trade deficit with India.

Second, India stands to lose the smooth cooperation it enjoyed with the recently dissolved Maoist-Congress coalition. During the dissolved government, the Nepali Congress held the Foreign Ministry, fostering a favorable equation for India. Just last month, Foreign Minister N.P. Saud visited India for the 9th Raisina Dialogue, engaging with top Indian officials, including his counterpart, S. Jaishankar.

As concerns arise for India regarding the Left Alliance, there is also potential for shifts in the partnership between Nepal and the United States, a significant development ally. Particularly, there may be a slowdown in the implementation of the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) projects. Despite facing domestic and Chinese opposition, the Nepali Parliament finally approved a $500 million MCC grant from the United States in 2022, following a five-year delay.

China perceives the MCC as a component of the U.S.-led Indo-Pacific strategy, countering its BRI. Hence Beijing aims to increase Chinese loans and subsidies to Nepal to enhance its influence.

To conclude, the re-emergence of Nepal’s Left Alliance signals a shift in power dynamics, impacting domestic politics and regional geopolitics. With China’s influence growing, Nepal’s foreign policy may tilt further toward Beijing, challenging India’s interests. This shift poses challenges for India, particularly in trade and diplomatic relations, while also affecting Nepal’s partnerships with other key players like the United States.

[[The Author,] Dr. Rishi Gupta is the assistant director of the Asia Society Policy Institute, Delhi]

6 Mar 24

229 notes

·

View notes

Text

Across the globe, a diverse group of nations that view world politics differently from the United States are rising and flexing their diplomatic muscle in ways that are complicating American statecraft. From Africa to Latin America, to the Middle East and Asia, these emerging powers refuse to fit into traditional U.S. thinking about the world order. The successful pursuit of American interests in the mid-21st century calls for a strategy that attracts them toward the United States and its ideals but without expecting them to line up in lockstep with Washington.

“We refuse to be a pawn in a new cold war,” Indonesian President Joko Widodo, known as Jokowi, said in November 2022. His views are shared in some form or another by leaders of Argentina, Brazil, India, Mexico, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Thailand, and Turkey. All 10 of these nations are either in the G-20 or have economies large enough to warrant membership. A majority of them have populations larger than Germany’s. Collectively, they make up around a third of the world’s population and a fifth of its economic production, while also constituting a major share of the so-called global south’s population and economic production.

In the next two decades, emerging powers like these will climb the ranks of the world’s largest economies and populations, reshaping the structure of world politics in the process. Their diplomacy is increasingly ambitious. And they are taking positions that run counter to those of the United States with growing boldness. Washington and its allies should accept not only that these powers are emerging, but also that as they grow stronger, they will not align with Washington’s preferences on many international issues, especially when it comes to Russia and China.

When Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, most of these powers declined to join the U.S.-led coalition to support Ukraine, refusing to take concrete action with sanctions on Russia or weapons for Kyiv. Some emerging powers, such as India and Turkey, even expanded economic ties with Russia.

Meanwhile, several of them pursued active diplomacy to end the war, challenging the U.S. policy of supporting Ukraine “as long as it takes.” Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, for example, pitched a plan to assemble a peace club to end the war and urged Washington to “stop encouraging war and start talking about peace.” Separately, Jokowi visited Kyiv and then Moscow, urging Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky and Russian President Vladimir Putin to start a dialogue. South Africa led a delegation of African leaders to end the war, and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has maintained a working relationship with Putin and sought to keep diplomatic channels open.

Most of these emerging powers also have warm ties with Beijing. They are reluctant to do anything that would endanger their economic relations with China. On a visit to Beijing in 2023, for example, Lula pledged to work with China to “balance world geopolitics”—a phrase that implied upending American global primacy. Even India, which sees China as an adversary and has grown much closer to the United States in recent years, is very unlikely to back the United States militarily in the event of a war over Taiwan.

Washington thus needs to avoid the urge to frame this world historical moment as a neo-Cold War ideological struggle. When the United States appeals to the emerging powers to sacrifice their interests for the liberal world order, they suspect that it is simply trying to woo them for its hard-power struggles with Russia and China. Their officials are quick to cite the 2003 Iraq War as evidence that Washington is not so committed as it claims to the liberal international order. They point to the many cases where the United States has compromised on its high principles and backed autocrats. President Joe Biden’s support for Israel’s campaign in Gaza has only given them another reason to doubt the veracity of American claims to exceptional moral authority.

Most of these emerging powers have limited political headroom anyway for ideological struggles of the kind that so often animate U.S. foreign policy. Indian Foreign Minister S. Jaishankar drove this point home when he pointed out that Europe’s ability to wean itself from Russian energy was a luxury that India did not have. “I have a population at $2,000 [per capita annual income],” he said. “I also need energy, and I am not in a position to pay high prices for oil.”

Given frictions between Washington and so many emerging powers of late, it can be tempting to disregard them and focus solely on countering Beijing and Moscow. But this would be a mistake. The emerging powers don’t pose a threat of the kind that U.S. adversaries can, but they also can’t just be ignored. China and Russia are certainly not going to ignore them—in fact, they are actively courting their leaders for political ties and market access with the hope of building a network of political and economic partners to obviate the need for ties to the West.

The emerging powers are also very open to China’s backing for alternative international institutions, such as the BRICS New Development Bank, that offer the prospect of infusions of capital without the bothersome conditions that accompany Western loans. They are critical of many aspects of the U.S.-led international order, which they see as dominated by former colonial powers and unfairly structured to serve the interests of the world’s wealthiest nations.

The good news for Washington is that the emerging powers don’t want to be vassals of China any more than they want to be vassals of America. They are not swing states ready to pick sides in a neo-Cold War. In fact, they actively seek a more fluid and multipolar world, one in which they believe they will have more leverage and freedom of maneuver. Many, moreover, maintain closer economic ties with the United States than China, especially when it comes to investment and defense cooperation.

Washington can make progress with these powers if it puts aside grand ideological framings about the liberal world order and focuses on developing a positive value proposition that offers meaningful benefit to their economic and political development, sovereignty, and aspirations for an enhanced voice in international affairs.

Although trade agreements have become politically unpopular for Republicans and Democrats alike, market access remains a powerful tool the United States has to this end. Other mutually beneficial economic arrangements are imaginable, focused on specific sectors and packages. So is cooperation on infrastructure investments, technology manufacturing, energy transition initiatives, deforestation, public health, and other areas.

Even when making progress on common interests, the emerging powers will also maintain substantial relationships with U.S. adversaries. Washington should not fall into the trap of judging the quality of its relations with the emerging powers by the strength of their ties to China or Russia.

Ultimately, the best way to engage with these nations is to help them strengthen their sovereignty so that they can resist the influence of U.S. adversaries and gain a real stake in sustaining a peaceful world order. This will take time and a change of approach but is likely to pay long-term benefits to America’s prosperity and continued global leadership.

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

May 17, 2023

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

MAY 18, 2023

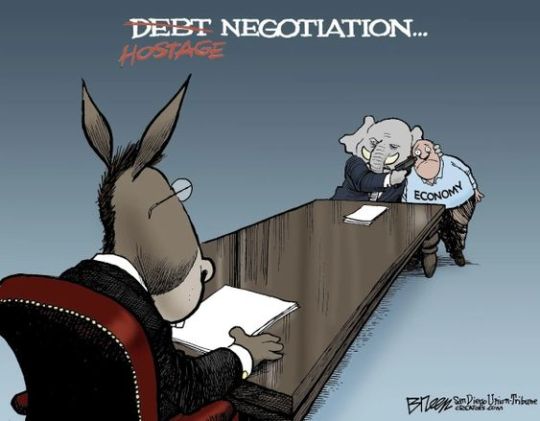

The debt ceiling crisis is already affecting our national security. Because President Biden has pulled out of his trip to Australia so he can come home to address the crisis, a planned meeting of the Quad will not go forward. The Quad, whose official name is the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, is a security group consisting of Australia, India, Japan and the United States that organized in 2007 as a response to China’s rising power.

Biden’s visit to Australia and to Papua New Guinea was designed to cement the interest of the U.S. in the Indo-Pacific region. Daniel Hurst of The Guardian was quite clear what it meant to have Biden forced to cancel because of the Republicans’ debt ceiling demands. His article on the issue was titled: “The cancelled Quad summit is a win for China and a self-inflicted blow to the US’s Pacific standing.” “Chinese state media outlets won’t need to muster much creative energy to weave together some of Beijing’s preferred narratives,” Hurst wrote, “that the US is racked by increasingly severe domestic upheaval and is an unreliable partner, quick to leave allies high and dry.”

In the Sydney Morning Herald, Matthew Knott called Biden’s forced withdrawal “a disappointment, a mess and a gift to Beijing.” “The US wants to remain the leader of the free world but domestic divisions mean it now regularly struggles to keep its government from shutting down and defaulting on its debts,” he wrote. “The Quad summit in Sydney should have provided a powerful symbol of four proud democracies working together to get things done. Instead, it will serve to highlight the systemic problems plaguing the world’s longest-standing democracy and its aspirations for ongoing global leadership.”

And, astonishingly, stepping on this global rake is an unforced error. The debt ceiling is not about future spending, it is about paying bills Congress has already incurred. If it comes to that, failing to raise the debt ceiling—the amount of money the Treasury can borrow to meet its obligations—so that Republicans, led by House Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-CA), can get concessions they cannot win through normal legislative procedures, will be an unforced error of truly epic proportions, a larger version of undercutting years of work building U.S. standing in the Indo-Pacific region.

Senate Democrats have begun to push for honoring the nation’s debts without trying to bring Republicans along. They are circulating a letter urging President Biden to invoke the fourth section of the Fourteenth Amendment to override the debt ceiling. That section reads: “The validity of the public debt of the United States, authorized by law, including debts incurred for payment of pensions and bounties for services in suppressing insurrection or rebellion, shall not be questioned.”

Republican congressmen wrote that section to prevent Democratic opponents, who hated the newly powerful government that had won the Civil War, from changing the terms of repayment of the debt. Democrats called for turning gold interest payments into payments in paper money. That change would have significantly degraded the value of the debt. It would also have destroyed confidence in the government, a result those who had just lost the Civil War quite liked.

Congress intended the Fourteenth Amendment to assert the power of the federal government over the states once and for all, making sure that no one could discriminate against individuals within the states or make war on the United States from within. It was an attempt to make it impossible for those trying to destroy the nation to carry out their plans.

Senator Peter Welch (D-VT) told Burgess Everett and Sarah Ferris of Politico, “It’s not about being comfortable with Biden or anyone else. It’s about the House. Kevin’s in shackles. He’s in leg, arms and hand cuffs. And frankly I don’t think he’s got much capacity to negotiate. And very little capacity to advance a deal.” Welch, who served eight terms in the House before moving to the Senate in 2023, added, “I’m quite pessimistic about McCarthy. He’s very constrained…. I think we’re heading toward a decision on the 14th Amendment.”

Interestingly, Senator Josh Hawley (R-MO) has indicated he’s on board with the idea of Biden invoking the Fourteenth Amendment. “I think if I were president, I would be tempted” to use the Fourteenth Amendment, Hawley said. “Because I would just be like, ‘Listen, I’m not gonna let us default. So end of story. Y’all will do whatever you want to do.’ But I’m not necessarily giving him that advice. It’s against my interest.” Hawley’s defense of the idea suggests that Republicans are eager to find a solution to the crisis that does not involve them, so that they can then condemn the Democrats for whatever they do.

—

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lula in China: The End of Brazil’s Flirtation With the Quad Plus

The new Lula administration has brought Brazil’s China policy back in line with its traditional approach, after the anti-China rhetoric of Jair Bolsonaro.

In 2018, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi dismissed the idea of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad), formed by the United States, Japan, India, and Australia, asserting that it would “dissipate like sea foam.” The Quad, created to facilitate the convergence of the four countries in terms of policies toward the Indo-Pacific, not only proved to be resilient over time but also intensified its activities in the region under both former U.S. President Donald Trump (2017-2021) and current President Joe Biden. During this period, the consultation between the group members went from being a biannual foreign ministerial dialogue to head of government-level consultations.

Analysts introduced the term Quad Plus in 2020 to describe a minilateral dialogue of states that extends the Quad beyond the four lynchpin democracies. However, while the term “Quad Plus” is not officially endorsed by Washington, Canberra, New Delhi, and Tokyo, it has become shorthand for non-Quad members that are closely cooperating with the group. That list includes other important U.S. partners such as Brazil, South Korea, Vietnam, Israel, New Zealand, and France. The idea originated during the uncertainty and global tensions at the time of the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The first concretization of the Quad Plus framework took place on March 20, 2020, when then-U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Stephen Biegun proposed a Quad meeting including Vietnam, New Zealand, and South Korea, which aimed to enable an exchange of assessments of the national pandemic situation of participant nations and align their responses to contain its spread. Later, a foreign ministers-level meeting in May 2020 with the participation of Israel, South Korea, and Brazil consolidated the Quad Plus with a global outlook. The extended initiative also materialized for the first time in the security realm in April 2021, when France led the La Pérouse Naval Exercise in the Bay of Bengal.

The unstated motivation of the Quad is the shared concern among the four original members about the rise of China’s international political and economic clout and the desire to check Beijing’s increasing military activities in the South and East China Seas. At the time, Brazil seemed to share such wariness in relation to Beijing since it was under the Jair Bolsonaro administration (2019-2022). The far-right former Brazilian Army captain aligned the country’s foreign policy to Washington’s interests. Bolsonaro also embraced fierce anti-Chinese rhetoric due to his distaste for Communism and China’s growing investments in sensitive Brazilian sectors like agriculture, meatpacking, and mining. Bolsonaro insinuated that China had engineered the COVID-19 virus and purposefully spread it worldwide to benefit from the pandemic economically.

Despite contentious relations with the East Asian power, Brasília failed to concretize a rapprochement with the Quad. It happened for three main reasons. First, Brazil is clueless about the Indo-Pacific. It lacks a full-fledged long-term strategy toward the region and has failed to include the very term “Indo-Pacific” in its official vocabulary. Brazil’s geographical position, facing the South Atlantic Ocean, and its limited capacities of naval power projection beyond marginal seas make it unlikely that Brasília will be able to ensure the freedom of navigation in a region half a world away. For example, among the last seven IBSAMAR Naval Exercises, carried out with India and South Africa, Brazil deployed an offshore patrol vessel to Goa only once.

Continue reading.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Military activity of China and Russia near Japan has increased 2.5 times since the beginning of the war in Ukraine

High-level coordinated maneuvers raise concerns in Tokyo.

Fernando Valduga By Fernando Valduga 07/15/2022 - 12:00 PM in Military, War Zones

Chinese and Russian military activity around Japan increased 2.5 times in the four months after Russia's invasion of Ukraine on February 24, awakening Japanese alarm about a potential escalation.

Statements from the Japanese Ministry of Defense show 90 cases of activity of Chinese and Russian military vessels and aircraft near Japan in the four months after the start of the invasion. There were 35 in the previous four months.

A Chinese ship and a Russian ship entered the contiguous area of Japan near the Japanese-run Senkaku Islands on July 4. China claims the islands as Diaoyu.

The Russian ship then sailed north through the Senkakus on July 5 before entering the contiguous zone near the southernmost islets of Okinotori of Japan the next day.

The type of activity recorded has also changed since the beginning of the invasion of Ukraine. On June 7, four aircraft believed to be part of the Russian armed forces flew straight to Japan, west of Hokkaido. They changed course shortly before entering Japanese airspace after the Japan Air Self-Defense Force sent fighters in response.

Before turning around, the four planes were on a trajectory towards the largest city of Sapporo, Hokkaido, a Japanese defense officer said. There is growing concern that such activity may be part of planned military operations in the area.

Ships from China and Russia circumnavigated Japan at the same time last month, in an unusual maneuver. Three Chinese ships began sailing north across the Sea of Japan from the Tsushima Strait in mid-June and split into two groups as they headed east towards the Pacific Ocean. They sailed through the Izu Islands on June 21 and northeast of the Miyako Islands on June 29.

Meanwhile, seven Russian ships were detected about 280 km southeast of Cape Erimo, in Hokkaido, on June 15. Some sailed south through the Pacific Ocean, then traveled north between the island of Okinawa and the Miyako Islands on the 19th. On June 21, they went northeast through the Tsushima Strait.

Although the ships have taken different routes, there is concern that they were testing their ability to coordinate in waters near Japan.

Japan and other Group of Seven nations banned imports of Russian coal, froze banking assets and imposed other sanctions on Moscow because of the war in Ukraine. Russian military activity is seen as a response to these penalties.

Chinese and Russian military activity increased in particular around May 22, when U.S. President Joe Biden visited Japan. A total of 43 instances were registered in May, compared to seven in April.

After a summit on May 23, Biden and Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida issued a joint statement calling for greater deterrent and response capacity under the bilateral alliance. A total of six Chinese and Russian bombers conducted a joint patrol near Japan while the leaders participated in a summit of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, or Quad, which also included Australia and India, in Tokyo on May 24.

"The recent actions of China and Russia are intended to show us: 'This is what we can do together, if necessary,'" said Ken Jimbo, a professor at the Keio University School of Policy Management. “These are high-level maneuvers conducted with real-life combat in mind.”

If Japan increases its defense spending, “it will need to adopt drones and other equipment and rethink its response,” he said.

Source: Nikkei Asia

Tags: Military AviationWar Zones - Indo-Asia-Pacific

Previous news

Universal Hydrogen presents its ATR 72 platform for testing with hydrogen cells

Next news

Russia suspends Czech and Bulgarian companies from repairing aircraft and helicopters of Russian origin

Fernando Valduga

Fernando Valduga

Aviation photographer and pilot since 1992, he has participated in several events and air operations, such as Cruzex, AirVenture, Dayton Airshow and FIDAE. He has works published in a specialized aviation magazine in Brazil and abroad. He uses Canon equipment during his photographic work in the world of aviation.

Related news

AERONAUTICAL ACCIDENTS

USAF Reaper drone accident in Romania

07/15/2022 - 7:00 PM

MILITARY

Boeing and U.S. Navy demonstrate manned/unmanned team in Super Hornet flight tests

07/15/2022 - 6:30 PM

AIR SHOWS

RAF reveals painting scheme of its Wedgetail AEW Mk1 (E-7) aircraft

07/15/2022 - 5:39 PM

MILITARY

The newest F-16 Fighting Falcon reaches its final assembly

07/15/2022 - 4:00 PM

MILITARY

Elbit Systems will supply DIRCM and EW systems for Dutch Air Force G650 aircraft

07/15/2022 - 3:00 PM

MILITARY

Russia suspends Czech and Bulgarian companies from repairing aircraft and helicopters of Russian origin

07/15/2022 - 14:00

HOME Main Page Editorials Information Events Collaborate SPECIALS Advertise About

Cavok Brasil - Digital Tchê Web Creation

Commercial

Executive

Helicopters

History

Military

Brazilian Air Force

Space

SPECIALS

Cavok Brasil - Digital Tchê Web Creation

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

August 20, 2022 (Saturday)

Earlier this month, on August 2, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and a Democratic delegation commanded headlines when they traveled to Taiwan, an independently governed East Asian country made up of 168 islands on which about 24 million people live, and which China claims. Since 1979 the U.S. has helped to maintain the defensive capabilities of the democratically governed area, although it has been vague about whether it would intervene if China attacks Taiwan.

Pelosi’s visit made her the highest-ranking U.S. politician to visit Taiwan since 1997, when Republican speaker Newt Gingrich visited the self-ruled island. Pelosi and a delegation of House Democrats who lead committees relevant to U.S. foreign relations—Gregory Meeks (NY), Mark Takano (CA), Suzan DelBene (WA), Raja Krishnamoorthi (IL), and Andy Kim (NJ)—visited Singapore, Malaysia, South Korea, and Japan. Taiwan was added quietly.

Since then, another, bipartisan, congressional delegation has visited Taiwan. Senator Ed Markey (D-MA); Representatives John Garamendi (D-CA), Alan Lowenthal (D-CA), and Don Beyer (D-VA); and Delegate Aumua Amata Coleman Radewagen (R–American Samoa) visited Taiwan earlier this week. Markey chairs the Senate Foreign Relations East Asia, Pacific, and International Cybersecurity Subcommittee, and Beyer is chair of the U.S. Congress Joint Economic Committee (JEC); the rest of the delegation represents people in or near the Pacific Ocean.

Before visiting Taiwan, Markey was in South Korea to talk about trade and technology, including the green technologies the U.S. is now funding through the Inflation Reduction Act, as well as “shared values and interests.

”There is a larger story behind these visits to Taiwan. Early this year, the Biden administration launched a new, comprehensive initiative in the Indo-Pacific. Beginning with the tsunami in the Indian Ocean in 2004, the U.S. began to work informally with the “Quad,” the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, consisting of the U.S., Australia, India, and Japan. In 2016, Japan introduced the concept of a free and open Indo-Pacific.

When former president Trump withdrew the U.S. from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, he left the participants to continue without the U.S., which they did as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). He also left open the way for a free trade deal in the region dominated by China, called the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement, or RCEP, which went into effect on January 1, 2022.

This left the Biden administration with two politically poor choices: try to reestablish U.S. participation in the region through the CPTPP, which would have been hotly contested at home and thus unlikely to get through Congress, or let China dominate the region, with damaging long-term effects. So the administration found a third way.

After some complaints that the administration had focused its attention too closely on the Middle East and Europe, in February the Biden administration released a document outlining its “Indo-Pacific Strategy,” claiming that the U.S. is part of the Indo-Pacific region, which stretches from our Pacific coastline to the Indian Ocean. The area, the report says, “is home to more than half of the world’s people, nearly two-thirds of the world’s economy, and seven of the world’s largest militaries. More members of the U.S. military are based in the region than in any other outside the United States. It supports more than three million American jobs and is the source of nearly $900 billion in foreign direct investment in the United States. In the years ahead, as the region drives as much as two-thirds of global economic growth, its influence will only grow—as will its importance to the United States.”

The document notes the long history of the U.S. and the countries in the region, and it warns against the rising power of the People’s Republic of China there. The document promises to compete responsibly with China by balancing influence in the world, creating an environment in the region “that is maximally favorable to the United States, our allies and partners, and the interests and values we share.”

Crucially, the document focuses not on the trade deals that made the TPP so unpopular, but on ideological ones, promoting “a free and open Indo-Pacific,” where countries “can make independent political choices free from coercion.” The U.S. will contribute to that atmosphere, the document says, “through investments in democratic institutions, a free press, and a vibrant civil society,” by strengthening partnerships within the region and outside it, such as the European Union and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). The plan promises that the U.S. will invest in the region through diplomacy, education, and security.

In May, President Joe Biden hosted the U.S.–Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Special Summit in the U.S. for the first time “to re-affirm the United States’ enduring commitment to Southeast Asia and underscore the importance of U.S.-ASEAN cooperation in ensuring security, prosperity, and respect for human rights.” And the State Department announced that “[t]he United States has provided over $12.1 billion in development, economic, health, and security assistance to Southeast Asian allies and partners since 2002, as well as over $1.4 billion in humanitarian assistance.”

Also in May, in Japan, Biden and a dozen Indo-Pacific nations announced a new, loose economic bloc, one that Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo has called “by any account the most significant international economic engagement that the United States has ever had in this region.” The bloc includes the U.S., India, Japan, South Korea, Australia, Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, New Zealand, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam, but not Taiwan. These countries represent about 40% of the global economy.

The new plan promised to streamline supply chains, back clean energy, fight corruption, and expand technology transfers. But with no guaranteed access to U.S. markets, there was uncertainty about how effective the administration’s calls for better labor and environmental standards would be.

Meanwhile, Secretary of State Antony Blinken also traveled to the region in early August, making stops in Cambodia, where he attended the U.S.-ASEAN ministerial meeting, the East Asia Summit Foreign Ministers’ Meeting, and the ASEAN Regional Forum, and in the Philippines. Before leaving, he promised to “emphasize the United States’ commitment to ASEAN centrality and successful implementation of the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific” and to “address the COVID-19 pandemic, economic cooperation, the fight against climate change, the crisis in Burma, and Russia’s war in Ukraine.” Chinese leaders warned the U.S. there would be “serious consequences” if Pelosi visited, and pundits suggested that she was reckless for going. But both Biden and Blinken made it clear that any potential visit would not mean any change in U.S. policy toward Taiwan, and 26 Republican lawmakers made a public statement praising the visit and noting that it has precedent.

Pelosi’s visit seemed to echo Biden and Blinken’s focus on world democracy. She championed Taiwan as a leading democracy, “a leader in peace, security and economic dynamism: with an entrepreneurial spirit, culture of innovation and technological prowess that are envies of the world.” She explicitly said her visit was intended to reaffirm “our shared interests [in]...advancing a free and open Indo-Pacific region.” “By traveling to Taiwan, we honor our commitment to democracy: reaffirming that the freedoms of Taiwan—and all democracies—must be respected.”

When Pelosi’s plane landed, China immediately announced live fire operations nearby and cut certain diplomatic communications with the U.S. But Director of the Centre for Russia Europe Asia Studies Theresa Fallon noted that the Chinese blockade/live fire exercise “is likely to boomerang on Xi. This will…scare just about every other country in Asia,” she wrote on Twitter. Yesterday, U.S. Ambassador to China Nicholas Burns, six months into the job, did his first television interview. Emphasizing that Pelosi’s visit was in keeping with longstanding history, he said, "We do not believe there should be a crisis in US-China relations over the visit—the peaceful visit—of the Speaker of the House of Representatives to Taiwan...it was a manufactured crisis by the government in Beijing. It was an overreaction.”

Burns added that it is now "incumbent upon the government here in Beijing to convince the rest of the world that it will act peacefully in the future” and observed that “there's a lot of concern around the world that China has now become an agent of instability in the Taiwan Strait and that's not in anyone's interest."

As drought, coronavirus lockdowns, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine hamstring the Chinese economy, China’s domination of the region seems wobbly. Apple is currently talking to Vietnam about making Apple Watches and MacBooks, moving production away from China. Vietnam already builds Apple products, but these new contracts would upgrade the Vietnamese technical sector in advance of what are expected to be more contracts.

(note - WHY NOT HAVE THESE MADE IN THE US??????)

This week, the EU and Indonesia launched their first ever joint naval exercise in the Arabian Sea, with an announcement that “[t]he EU and Indonesia are committed to a free, open, inclusive and rules-based order in the Indo-Pacific region, underpinned by respect for territorial integrity and sovereignty, democracy, rule of law, transparency, freedom of navigation and overflight, unimpeded lawful commerce, and peaceful resolution of disputes. They reaffirm the primacy of international law, including the United Nations Convention on Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).”The U.S. and Taiwan, which was not included in the earlier economic organization, will start formal trade talks in the fall.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Holidays 4.28

Holidays

Astronomy Day

Biological Clock Day

Bulldogs Are Beautiful Day

Chicken Tickling Day

Clean Comedy Day

Cubicle Day

Day for Safety and Health at Work (Poland)

Day of Dialogue

Days of Remembrance of Victims of the Holocaust, Day 1 (US)

Eat Your Friends Day

Ed Balls Day (UK)

Flag Day (Åland Islands)

Flat White Day

Food Pyramid Day

428 Day

Global Pay It Forward Day

Gone-ta-Pott Day [every 28th]

Great Poetry Reading Day

Hyacinth Day (French Republic)

International Astronomy Day

International Automation Professionals Day

International Consanguinamory Day

International Girls in Information and Telecommunication Technologies Day

Jester’s Day (Elder Scrolls)

Kenneth Kaunda Day (Zambia)

Kiss Your Mate Day

Lawyers’ Day (India)

Mujahideen Victory Day (Afghanistan)

Mutiny On the Bounty Day

National Anger Day (UK)

National BSL Day (UK)

National Brave Hearts Day

National Cubicle Day

National Day of Mourning (Canada)

National Franklin Day

National Great Poetry Reading Day

National Headshot Day

National Heroes’ Day (Barbados)

National Kiss Your Mate Day

National Poetry and Literature Day (Indonesia)

National “Say Hi to Joe” Day

National Suck Breast Day

National Superhero Day

National Teach Children to Save Day

National Willy Fog Day (UK)

National Workplace Wellbeing Day (Ireland)

Occupational Safety & Health Day

Pastele Blajinilor (Memory or Parent's Day; Moldova)

Restoration of Sovereignty Day (Japan)

Rip Cord Day

Saint Pierre-Chanel Day (Wallis and Futuna)

Santa Fe Trail Day

Sardinia Day (Italy)

Small Car Day

Steel Safety Day

Texas Wildflower Day

Turkmen Racing Horse Festival (Turkmenistan)

Victory Day (Afghanistan)

Workers’ Memorial Day (Gibraltar)

World Art Deco Day

World Day for Safety and Health at Work (UN)

Food & Drink Celebrations

National Blueberry Pie Day

4th & Last Sunday in April

Blue Sunday [Last Sunday]

Brasseries Portes Ouvertes (Open Breweries' Day; Belgium) [Last Sunday]

Dictionary Day [Sunday of Nat’l Library Week]

Divine Mercy Sunday [Last Sunday]

Drive It Day (UK) [4th Sunday]

Family Reading Week begins [Sunday before 1st Saturday in May]

International Search and Rescue Dog Day [Last Sunday]

International Twin Cities Day [Last Sunday]

Landsgemeinde (Switzerland) [Last Sunday]

Mother, Father Deaf Day [Last Sunday]

Music Minister Appreciation Day [Last Sunday]

National Blue Sunday and Day of Prayer for Abused Children [Last Sunday]

National Pet Parents Day [Last Sunday]

Pinhole Photography Day [Last Sunday]

Sunday of the Paralytic [Last Sunday]

Turkmen Racing Horse Festival (Turkmenistan) [Last Sunday]

World Day of Marriage [Last Sunday]

World Nyckelharpa Day [Last Sunday]

Worldwide Pinhole Photography Day [Last Sunday]

Weekly Holidays beginning April 28 (Last Week)

Go Diaper Free Week (thru 5.4) [From Last Sunday]

National Auctioneers Week (thru 5.4)

National Small Business Week (thru 5.4) [1st Week of May]

Preservation Week (thru 5.4)

Stewardship Week (thru 5.5) [Last Sunday to 1st Sunday]

Independence & Related Days

Maryland Statehood Day (#7; 1788)

Restoration of Sovereignty Day (Japan)

Festivals Beginning April 28, 2024

Blessing of the Fleet & Seafood Festival (Mount Pleasant, South Carolina)

The Good Food Awards (Portland, Oregon)

Heritage Fire (Atlanta, Georgia)

St. Thomas Carnival (Charlotte Amalie, U.S. Virgin Islands) [thru 5.5]

Sweet Corn Fiesta (West Palm Beach, Florida)

Taste of St. Augustine (St. Augustine, Florida)

Turkmen Racing Horse Festival (Turkmenistan) [Last Sunday]

Feast Days

Aphrodisius and companions (Christian; Saint)

Blueberry Pie Day (Pastafarian)

Chicken Tickling Day (Leprechauns; Shamanism)

Cronan of Roscrea, Ireland (Christian; Saint)

Cyril of Turov (Christian; Saint)

Didymus and Theodore (Christian; Martyrs)

Elmo’s Jacket (Muppetism)

Feast of Jamál (Beauty; Baha'i)

Floralia (Old Roman Goddess of Flowers)

Gianna Beretta Molla (Christian; Saint)

Harper Lee (Writerism)

José Malhoa (Artology)

Kirill of Turov (Orthodox, added to Roman Martyrology in 1969)

L’Africaine (The African Woman), by Giacomo Meyerbeer (Opera; 1865)

Louis Mary de Montfort (Christian; Saint)

Palmer Day (Church of the SubGenius; Saint)

Pamphilus of Sulmona (Christian; Saint)

Patricius, Bishop of Pruse, in Bithynia (Christian; Saint)

Paul of the Cross (Christian; Saint)

Peter Chanel (Christian; Martyr)

Phocion (Positivist; Saint)

Pollio and others (Christian; Martyrs in Pannonia)

Terry Pratchett (Writerism)

Theodora and Didymus (Christian; Martyrs)

Vitalis and Valeria of Milan (Christian; Saint)

Walpurgisnacht, Day VI (Pagan)

Yom HaShoah (began last night; Judaism)

Yves Klein (Artology)

Orthodox Christian Liturgical Calendar Holidays

Palm Sunday

Lucky & Unlucky Days

Butsumetsu (仏滅 Japan) [Unlucky all day.]

Fortunate Day (Pagan) [17 of 53]

Umu Limnu (Evil Day; Babylonian Calendar; 20 of 60)

Premieres

Akeelah and the Beer (Film; 2006)

The Art of Excellence, by Tony Bennett (Album; 1987) [1st CD-only Release]

Bananas (Film; 1971)

Before These Crowded Street, by Crowded House (Album; 1998)

The Birth of Britain, by Winston Churchill (History Book; 1956)

Bridesmaids (Film; 2011)

Buck and the Preacher (Film; 1972)

Casino Royale (Film; 1967) [James Bond non-series film]

Chicago Transit Authority, by Chicago (Album; 1969)

The Death of the Heart, by Elizabeth Bowen (Novel; 1938)

FM (Film; 1978)

Frequency (Film; 2000)

Hair (Broadway Musical; 1968)

Hard Candy (Film; 2006)

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (Film; 2005)

The Hockey Champ (Disney Cartoon; 1939)

A Hound for Trouble (WB MM Cartoon; 1951)

How to Be a Latin Lover (Film; 2017)

I Kissed a Girl, by Katy Perry (Song; 2008)

I’m the One, by DJ Khaled (Album; 2017)

Iron Man 2 (Film; 2010)

Kiss Me Deadly (Film; 1955)

Leave Well Enough Alone (Fleischer Popeye Cartoon; 1939)

Love Me, Love My Mouse (Tom & Jerry Cartoon; 1966)

Loverboy (Film; 1989)

Mighty Mouse Meets Jekyll and Hyde Cat (Terrytoons Cartoon; 1944)

Mud Squad (Tijuana Toads Cartoon; 1971)s

Night (Disney Cartoon; 1930)

Odd Ant Out (Ant and the Aardvark Cartoon; 1970)

A Painted House, by John Grisham (Novel; 2001)

Passport to Pimlico (Film; 1949)

Pennsylvania 6-5000, recorded by Glenn Miller (Song; 1940)

Polite Society (Film; 2023)

The Power of Positive Thinking, by Norman Vincent Peale (Book; 1954)

The Prison Panic (Oswald the Lucky Rabbit Cartoon; 1930)

Problem, by Ariana Grande (Song; 2014)

Robinson Crusoe (WB LT Cartoon; 1956)

The Secret of the Old Clock, by Carolyn Keene (Mystery Novel; 1930) [1st Nancy Drew]

*61 (Film; 2001)

Slave to Love, by Bryan Ferry (Song; 1985)

Smoked Hams (Woody Woodpecker Cartoon; 1947)

Starman, by David Bowie (Song; 1972)

Stick It (Film; 2006)

Suddenly It’s Spring (Noveltoons Cartoon; 1944)

Suffragette City, by David Bowie (Song; 1972)

Trailer Horn (Disney Cartoon; 1950)

Viva Las Vegas, by Elvis Presley (Song; 1964)

Today’s Name Days

Hugo, Ludwig, Pierre (Austria)

Dada, Ljudevit, Petar (Croatia)

Vlastislav (Czech Republic)

Vitalis (Denmark)

Lagle, Luige (Estonia)

Ilpo, Ilppo, Tuure (Finland)

Valérie (France)

Hugo, Ludwig, Pierre (Germany)

Valéria (Hungary)

Manilio, Pietro, Valeria (Italy)

Gundega, Gunta, Terēze (Latvia)

Rimgailė, Valerija, Vitalius, Vygantas (Lithuania)

Vivi, Vivian (Norway)

Arystarch, Maria, Paweł, Przybyczest, Waleria, Witalis (Poland)

Iason, Sosipatru (Romania)

Tamara (Russia)

Jarmila (Slovakia)

Luis, Pedro, Prudencio (Spain)

Ture, Tyra (Sweden)

Valeria, Valerian, Valerie, Valery (USA)

Today is Also…

Day of Year: Day 119 of 2024; 247 days remaining in the year

ISO: Day 7 of week 17 of 2024

Celtic Tree Calendar: Saille (Willow) [Day 15 of 28]

Chinese: Month 3 (Wu-Chen), Day 20 (Ren-Xu)

Chinese Year of the: Dragon 4722 (until January 29, 2025) [Wu-Chen]

Hebrew: 20 Nisan 5784

Islamic: 19 Shawwal 1445

J Cal: 29 Cyan; Eightday [29 of 30]

Julian: 15 April 2024

Moon: 79%: Waning Gibbous

Positivist: 7 Caesar (5th Month) [Themistocles]

Runic Half Month: Lagu (Flowing Water) [Day 4 of 15]

Season: Spring (Day 41 of 92)

Week: 4th Week of April / 1st Week of May

Zodiac: Taurus (Day 9 of 31)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Holidays 4.28

Holidays

Astronomy Day

Biological Clock Day

Bulldogs Are Beautiful Day

Chicken Tickling Day

Clean Comedy Day

Cubicle Day

Day for Safety and Health at Work (Poland)

Day of Dialogue

Days of Remembrance of Victims of the Holocaust, Day 1 (US)

Eat Your Friends Day

Ed Balls Day (UK)

Flag Day (Åland Islands)

Flat White Day

Food Pyramid Day

428 Day

Global Pay It Forward Day

Gone-ta-Pott Day [every 28th]

Great Poetry Reading Day

Hyacinth Day (French Republic)

International Astronomy Day

International Automation Professionals Day

International Consanguinamory Day

International Girls in Information and Telecommunication Technologies Day

Jester’s Day (Elder Scrolls)

Kenneth Kaunda Day (Zambia)

Kiss Your Mate Day

Lawyers’ Day (India)

Mujahideen Victory Day (Afghanistan)

Mutiny On the Bounty Day

National Anger Day (UK)

National BSL Day (UK)

National Brave Hearts Day

National Cubicle Day

National Day of Mourning (Canada)

National Franklin Day

National Great Poetry Reading Day

National Headshot Day

National Heroes’ Day (Barbados)

National Kiss Your Mate Day

National Poetry and Literature Day (Indonesia)

National “Say Hi to Joe” Day

National Suck Breast Day

National Superhero Day

National Teach Children to Save Day

National Willy Fog Day (UK)

National Workplace Wellbeing Day (Ireland)

Occupational Safety & Health Day

Pastele Blajinilor (Memory or Parent's Day; Moldova)

Restoration of Sovereignty Day (Japan)

Rip Cord Day

Saint Pierre-Chanel Day (Wallis and Futuna)

Santa Fe Trail Day

Sardinia Day (Italy)

Small Car Day

Steel Safety Day

Texas Wildflower Day

Turkmen Racing Horse Festival (Turkmenistan)

Victory Day (Afghanistan)

Workers’ Memorial Day (Gibraltar)

World Art Deco Day

World Day for Safety and Health at Work (UN)

Food & Drink Celebrations

National Blueberry Pie Day

4th & Last Sunday in April

Blue Sunday [Last Sunday]

Brasseries Portes Ouvertes (Open Breweries' Day; Belgium) [Last Sunday]

Dictionary Day [Sunday of Nat’l Library Week]

Divine Mercy Sunday [Last Sunday]

Drive It Day (UK) [4th Sunday]

Family Reading Week begins [Sunday before 1st Saturday in May]

International Search and Rescue Dog Day [Last Sunday]

International Twin Cities Day [Last Sunday]

Landsgemeinde (Switzerland) [Last Sunday]

Mother, Father Deaf Day [Last Sunday]

Music Minister Appreciation Day [Last Sunday]

National Blue Sunday and Day of Prayer for Abused Children [Last Sunday]

National Pet Parents Day [Last Sunday]

Pinhole Photography Day [Last Sunday]

Sunday of the Paralytic [Last Sunday]

Turkmen Racing Horse Festival (Turkmenistan) [Last Sunday]

World Day of Marriage [Last Sunday]

World Nyckelharpa Day [Last Sunday]

Worldwide Pinhole Photography Day [Last Sunday]

Weekly Holidays beginning April 28 (Last Week)

Go Diaper Free Week (thru 5.4) [From Last Sunday]

National Auctioneers Week (thru 5.4)

National Small Business Week (thru 5.4) [1st Week of May]

Preservation Week (thru 5.4)

Stewardship Week (thru 5.5) [Last Sunday to 1st Sunday]

Independence & Related Days

Maryland Statehood Day (#7; 1788)

Restoration of Sovereignty Day (Japan)

Festivals Beginning April 28, 2024

Blessing of the Fleet & Seafood Festival (Mount Pleasant, South Carolina)

The Good Food Awards (Portland, Oregon)

Heritage Fire (Atlanta, Georgia)

St. Thomas Carnival (Charlotte Amalie, U.S. Virgin Islands) [thru 5.5]

Sweet Corn Fiesta (West Palm Beach, Florida)

Taste of St. Augustine (St. Augustine, Florida)

Turkmen Racing Horse Festival (Turkmenistan) [Last Sunday]

Feast Days

Aphrodisius and companions (Christian; Saint)

Blueberry Pie Day (Pastafarian)

Chicken Tickling Day (Leprechauns; Shamanism)

Cronan of Roscrea, Ireland (Christian; Saint)

Cyril of Turov (Christian; Saint)

Didymus and Theodore (Christian; Martyrs)

Elmo’s Jacket (Muppetism)

Feast of Jamál (Beauty; Baha'i)

Floralia (Old Roman Goddess of Flowers)

Gianna Beretta Molla (Christian; Saint)

Harper Lee (Writerism)

José Malhoa (Artology)

Kirill of Turov (Orthodox, added to Roman Martyrology in 1969)

L’Africaine (The African Woman), by Giacomo Meyerbeer (Opera; 1865)

Louis Mary de Montfort (Christian; Saint)

Palmer Day (Church of the SubGenius; Saint)

Pamphilus of Sulmona (Christian; Saint)

Patricius, Bishop of Pruse, in Bithynia (Christian; Saint)

Paul of the Cross (Christian; Saint)

Peter Chanel (Christian; Martyr)

Phocion (Positivist; Saint)

Pollio and others (Christian; Martyrs in Pannonia)

Terry Pratchett (Writerism)

Theodora and Didymus (Christian; Martyrs)

Vitalis and Valeria of Milan (Christian; Saint)

Walpurgisnacht, Day VI (Pagan)

Yom HaShoah (began last night; Judaism)

Yves Klein (Artology)

Orthodox Christian Liturgical Calendar Holidays

Palm Sunday

Lucky & Unlucky Days

Butsumetsu (仏滅 Japan) [Unlucky all day.]

Fortunate Day (Pagan) [17 of 53]

Umu Limnu (Evil Day; Babylonian Calendar; 20 of 60)

Premieres

Akeelah and the Beer (Film; 2006)

The Art of Excellence, by Tony Bennett (Album; 1987) [1st CD-only Release]

Bananas (Film; 1971)

Before These Crowded Street, by Crowded House (Album; 1998)

The Birth of Britain, by Winston Churchill (History Book; 1956)

Bridesmaids (Film; 2011)

Buck and the Preacher (Film; 1972)

Casino Royale (Film; 1967) [James Bond non-series film]

Chicago Transit Authority, by Chicago (Album; 1969)

The Death of the Heart, by Elizabeth Bowen (Novel; 1938)

FM (Film; 1978)

Frequency (Film; 2000)

Hair (Broadway Musical; 1968)

Hard Candy (Film; 2006)

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (Film; 2005)

The Hockey Champ (Disney Cartoon; 1939)

A Hound for Trouble (WB MM Cartoon; 1951)

How to Be a Latin Lover (Film; 2017)

I Kissed a Girl, by Katy Perry (Song; 2008)

I’m the One, by DJ Khaled (Album; 2017)

Iron Man 2 (Film; 2010)

Kiss Me Deadly (Film; 1955)

Leave Well Enough Alone (Fleischer Popeye Cartoon; 1939)

Love Me, Love My Mouse (Tom & Jerry Cartoon; 1966)

Loverboy (Film; 1989)

Mighty Mouse Meets Jekyll and Hyde Cat (Terrytoons Cartoon; 1944)

Mud Squad (Tijuana Toads Cartoon; 1971)s

Night (Disney Cartoon; 1930)

Odd Ant Out (Ant and the Aardvark Cartoon; 1970)

A Painted House, by John Grisham (Novel; 2001)

Passport to Pimlico (Film; 1949)

Pennsylvania 6-5000, recorded by Glenn Miller (Song; 1940)

Polite Society (Film; 2023)

The Power of Positive Thinking, by Norman Vincent Peale (Book; 1954)

The Prison Panic (Oswald the Lucky Rabbit Cartoon; 1930)

Problem, by Ariana Grande (Song; 2014)

Robinson Crusoe (WB LT Cartoon; 1956)

The Secret of the Old Clock, by Carolyn Keene (Mystery Novel; 1930) [1st Nancy Drew]

*61 (Film; 2001)

Slave to Love, by Bryan Ferry (Song; 1985)

Smoked Hams (Woody Woodpecker Cartoon; 1947)

Starman, by David Bowie (Song; 1972)

Stick It (Film; 2006)

Suddenly It’s Spring (Noveltoons Cartoon; 1944)

Suffragette City, by David Bowie (Song; 1972)

Trailer Horn (Disney Cartoon; 1950)

Viva Las Vegas, by Elvis Presley (Song; 1964)

Today’s Name Days

Hugo, Ludwig, Pierre (Austria)

Dada, Ljudevit, Petar (Croatia)

Vlastislav (Czech Republic)

Vitalis (Denmark)

Lagle, Luige (Estonia)

Ilpo, Ilppo, Tuure (Finland)

Valérie (France)

Hugo, Ludwig, Pierre (Germany)

Valéria (Hungary)

Manilio, Pietro, Valeria (Italy)

Gundega, Gunta, Terēze (Latvia)

Rimgailė, Valerija, Vitalius, Vygantas (Lithuania)

Vivi, Vivian (Norway)

Arystarch, Maria, Paweł, Przybyczest, Waleria, Witalis (Poland)

Iason, Sosipatru (Romania)

Tamara (Russia)

Jarmila (Slovakia)

Luis, Pedro, Prudencio (Spain)

Ture, Tyra (Sweden)

Valeria, Valerian, Valerie, Valery (USA)

Today is Also…

Day of Year: Day 119 of 2024; 247 days remaining in the year

ISO: Day 7 of week 17 of 2024

Celtic Tree Calendar: Saille (Willow) [Day 15 of 28]

Chinese: Month 3 (Wu-Chen), Day 20 (Ren-Xu)

Chinese Year of the: Dragon 4722 (until January 29, 2025) [Wu-Chen]

Hebrew: 20 Nisan 5784

Islamic: 19 Shawwal 1445

J Cal: 29 Cyan; Eightday [29 of 30]

Julian: 15 April 2024

Moon: 79%: Waning Gibbous

Positivist: 7 Caesar (5th Month) [Themistocles]

Runic Half Month: Lagu (Flowing Water) [Day 4 of 15]

Season: Spring (Day 41 of 92)

Week: 4th Week of April / 1st Week of May

Zodiac: Taurus (Day 9 of 31)

1 note

·

View note

Text

The U.S. policy on Myanmar is all wrong

#peace#Burma

NEW DELHI - U.S. President Joe Biden and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi recently issued a joint statement "expressing deep concern about the deteriorating situation in Myanmar" and calling for constructive dialogue to help the country transition to an inclusive federal democracy. Unfortunately, U.S.-led sanctions undermine this goal and make the situation worse.

Western sanctions, while inflicting pain on ordinary Myanmar citizens, have left the ruling military elite relatively unscathed, leaving the military junta with no incentive to loosen political control. The main beneficiary is China, which has been able to expand its foothold in a country it sees as a strategic gateway to the Indian Ocean and a vital source of natural resources.

This development has exacerbated regional security challenges. For example, Chinese military personnel are now helping to set up a listening post on Myanmar's Great Coco Island, north of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands where the Indian military's only tri-services command is located. Once operational, the new spy station is likely to assist China in its maritime surveillance of India, including monitoring the movements of nuclear submarines and tracking missile tests that often land in the Bay of Bengal.

0 notes

Text

NATO is seeking to expand its cooperation structures globally and also intensify its cooperation with Jordan, Indonesia and India. A “NATO-Indonesia meeting” was held yesterday (Wednesday) on the sidelines of the NATO foreign ministers’ meeting in Brussels – a follow-up to talks between Indonesia’s Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi and NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg in mid-June 2022. Last week, a senior NATO official visited Jordan’s capital Amman to promote the establishment of a NATO liaison office. Already back in June, a US Congressional Committee focused on China, had advocated linking India more closely to NATO. India’s External Affairs Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar, however, quickly rejected the suggestion. NATO diplomats are quoted saying that the Western military alliance could conceive of cooperating with South Africa or Brazil, for example. These plans would escalate the West’s power struggle against Russia and China, while non-Western alliances such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) are expanding their membership.

Already since some time, NATO has been seeking to expand its cooperation structures into the Asia-Pacific region, for example to include Japan. Early this year, NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg was in Tokyo, among other things, to sign a joint declaration with Prime Minister Fumio Kishida.[1] In addition, it is strengthening its cooperation with South Korea, whose armed forces are participating in NATO cyber defense and are to be involved more intensively in future conventional NATO maneuvers.[2] Japan’s prime minster and South Korea’s president have already regularly attended NATO summits. The Western military alliance is also extending its cooperation with Australia and New Zealand. This development is not without its contradictions. France, for example, opposes the plan to establish a NATO liaison office in Japan, because it considers itself an important Pacific power and does not want NATO’s influence to excessively expand in the Pacific. Nevertheless, the Western military alliance is strengthening its presence in the Asia-Pacific region – with maneuvers conducted by its member states, including Germany (german-foreign-policy.com reported.[3]).[...]

NATO has been cooperating with several Mediterranean countries since 1994 within the framework of its Mediterranean Dialogue and also since 1994, with several Arab Gulf countries as part of its Istanbul Cooperation Initiative.[4] However, the cooperation is not considered very intensive. At the beginning of this week, NATO diplomats have been quoted saying “we remain acutely aware of developments on our southern flank,” and are planning appropriate measures. The possibility of establishing a Liaison Office in Jordan is being explored “as a move to get closer to the ground and develop the relationship in the Middle East.[5] Last week, a senior NATO official visited Jordan’s capital Amman to promote such a liaison office.[6][...]

NATO diplomats informed the online platform “Euractiv” that “many members of the Western military alliance believe that political dialogue does not have to be limited to the southern neighborhood. One can also seek cooperation with states further away. Brazil, South Africa, India, and Indonesia are mentioned as examples.[7][...]

In a paper containing strategic proposals for the U.S. power struggle against China, the Committee also advocated strengthening NATO’s cooperation with India.[8] The proposal caused a stir in the run-up to Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Washington on June 22. He was able to draw on the fact that India is cooperating militarily in the Quad format with the USA as well as NATO partners Japan and Australia in order to gain leverage against China. Close NATO ties could also facilitate intelligence sharing, allowing New Delhi to access advanced military technology.[9] India’s External Affairs Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar, however, rejected Washington’s proposal, stating that the “NATO template does not apply to India”.[10] Indian media explained that New Delhi was still not prepared to be pitted against Russia and to limit its independence.[11] Both would be entailed in close ties to NATO.

The efforts to link third countries around the world more closely to NATO are being undertaken at a time when not only western countries are escalating their power struggles against Russia and above all against China and are therefore tightening their alliance structures. They are also taking place when non-Western alliances are gaining ground. This is true not only for the BRICS, which decided, in August, to admit six new members on January 1, 2024 (german-foreign-policy.com reported [12]). This is also true for the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), a security alliance centered around Moscow and Beijing that has grown from its original six to currently nine members, including India, Pakistan and Iran, and continues to attract new interested countries. In addition to several countries in Southern Asia and the South Caucasus, SCO “dialogue partners” now include Turkey, Egypt and five Arabian Peninsula states, including Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Qatar. Iin light of the BRICS expansion, the admission of additional countries as full SCO members is considered quite conceivable. Western dominance will thus be progressively weakened.[13]

12 Oct 23

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

For more than 50 years, and especially since the Iranian revolution of 1979, U.S. policies and initiatives in the Middle East rested on a complex network of relations with four diverse regional pillars: Saudi Arabia, Israel, Turkey, and Egypt. At one time or another the United States worked with one or more of these states to contain the perennial fires ravaging the region (even when these same states ignited the fires in the first place, whether Saudi Arabia in Yemen, Israel in Lebanon and the occupied Palestinian territories, or Turkey in Iraq and Syria).

Over the years, the U.S. achieved some notable victories in the region, alone or with these erstwhile allies. But the world that gave rise to these relationships is undergoing changes that require a serious, even radical, reevaluation. There is no longer a Soviet threat to the Gulf region, and the U.S. has become the largest oil producer in the world. Meanwhile, the last U.S.-sponsored peace talks between Palestinians and Israelis collapsed almost a decade ago, the two-state solution has long been dead, and the extremists in charge of Israel today are on a messianic mission to formally annex all the Palestinian territories under their control.

The leaders of Saudi Arabia, Israel, Turkey, and Egypt have been charting their own paths, flagrantly disregarding Washington’s core interests. They believe that closer political, economic, and military relations with Russia, China, India, or each other—openly or clandestinely—will provide them with suitable alternatives to the United States. To put it bluntly, America’s four traditional pillars in the Middle East are now too brittle to be relied upon.

Much has been written recently about how the Turks, Israelis, and Arabs have been involved in dialogue with one another, exploring ways to revive regional diplomacy, cooperation, and investment. Some analysts went as far as to proclaim the dawn of a new era in the Middle East. But these de-escalations should be welcomed with much caution. The men who today sing the virtues of reconciliation were the same ones who ravaged Yemen; laid siege to Qatar; rampaged in Syria and Libya; and shunned Bashar al-Assad, Syria’s despot, after a popular uprising, only to welcome him after he committed war crimes and turned his country into a narcostate.

In reality, Saudi Arabia, Israel, Turkey, and Egypt have all been pursuing various forms of aggressive nationalism. Israel has already codified religious chauvinism and exclusivism, and some of its leaders regularly incite terrorism and call for the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians from the West Bank. In Saudi Arabia, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman has fostered a new culture of hyper-nationalism in an attempt to diminish the influence of the religious establishment and build by coercive means a Saudi national identity revolving around his authoritarian persona.

In Turkey, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is known for stirring up a version of aggressive Turkish nationalism, laced with religious overtones and mixed with Ottoman revivalism in his frequent campaigns of grievances and intimidation against the West. Erdogan projects himself as the embodiment of these corrosive values. And in Egypt, President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi’s decade-long reign has been the most autocratic and disastrous in modern Egyptian history.

Moreover, these countries have mostly stopped cooperating with the United States on its regional priorities. Sisi was planning to provide rockets and artillery rounds to Russia to use against Ukraine before he was caught by U.S. intelligence agencies earlier this year. Erdogan only barely managed to maneuver his way out of a major crisis with U.S. President Joe Biden and other NATO powers at the recent Vilnius summit, when he seemed to drop his opposition to Sweden’s accession to NATO after a year of obstruction. But his blackmailing of Europe by threatening to unleash waves of Syrian refugees continues. And Erdogan’s earlier purchase of the Russian S-400 missile defense system should have warranted harsher sanctions than it received.

The historical factors that once cemented ties to the United States have also dissipated. The Soviet Union, which posed a threat to the countries of the region, is no more. (Ironically, Russian President Vladimir Putin today enjoys warmer personal relations with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, Mohammed bin Salman, and Erdogan than these leaders enjoy with Biden.) There are no longer any foreign threats to the Gulf.

The role played by oil has also changed dramatically. Oil had fueled America’s relations with Saudi Arabia dating back to World War II, with the U.S. and its allies in Europe and Asia coming to rely on imported oil and gas from Saudi Arabia and the rest of the Gulf states in exchange for the U.S. military guaranteeing the safety of these transactions. But the United States is no longer the lone outside power with an economic stake in the Gulf region. Asian powers such as China, India, and others have established or reestablished complex economic and trade relations with the Gulf. And it is only natural that higher economic Asian activity will bring with it a higher political and military profile.

And, in truth, this marks the return of a deeper history for the region. Long before the onset of large oil revenues, Gulf port cities resembled Indian Ocean port cities. The economies of these small port cities were dominated by merchant families: Arab, Persian, African, Baluch, Indian, and others, with Sunnis and Shiites living on both sides of the Gulf. Over the centuries, these families developed a rich maritime culture that created a complex exchange of people and goods across the Gulf cities, East Africa, and the port cities of the Indian subcontinent and beyond. These renowned traders with their ubiquitous dhows traversed these waters long before Western powers controlled them. For the new Gulf states to look eastward is nothing more than to reestablish the old maritime lanes.

Seen in this context, the hyperventilation in some official quarters in Washington and among the commentariat class over China’s limited role in reestablishing diplomatic relations between Saudi Arabia and Iran is both unwarranted and exaggerated. Most of the initial hard work was achieved earlier in quiet talks in Baghdad and Oman, until the Saudi leadership, with an eye on catching Washington’s attention, brought in China to produce and direct the last scene, giving Beijing credit for the whole production. The Biden administration responded as expected, which explains, in part at least, its current unseemly scramble to make peace between Saudi Arabia and Israel.

For the foreseeable future, no state or combination of states could seriously undermine America’s strategic, economic, and technical edge in the Gulf region, and the U.S. should make it clear to the Arab Gulf states that reckless cavorting with China at the expense of the United States will have consequences. (We should note that the Saudis made their first clandestine purchase of medium-range missile systems from China in the 1980s.) Riyadh is not about to halt its long Western orientation. American technology and expertise will continue to be essential for the Saudi energy sector, which remains the kingdom’s main source of income; we are not about to witness thousands of young Saudi students flocking to Beijing and Shanghai to study Mandarin.

The Biden administration’s seeming obsession with mediating a deal between Saudi Arabia and Israel to formalize their existing de facto normalization is a Sisyphean labor—one that, even if it is partially successful, will not benefit the U.S. politically or strategically in the long run. Its primary political result will be to strengthen the authoritarian rule of Mohammed bin Salman and embolden Netanyahu in his establishment of a more fundamentalist Israel. And such a deal, regardless of any assurances given to the Palestinians, will hardly change their fundamental lived reality—that of occupation and the denial of basic rights.

The price Saudi Arabia is trying to extract from the Biden administration—including more extensive security guarantees that would elevate the kingdom to the status of other U.S. formal allies, nuclear technology for a civilian energy program, and freer access to U.S. arms—is a burden too much to bear. Saudi Arabia, given Mohammed bin Salman’s character and aggressive history, is not a partner worthy of the price. The crown prince is exploiting Washington’s exaggerated fears of an assertive China in the Gulf region to gain concessions the U.S. will live to regret. A Saudi-Israeli peace deal, if it materializes, will at best be a deal among the existing elites of both countries, and accelerate the regional drift toward more autocracy and authoritarianism. Such a deal will not guarantee at all that Mohammed bin Salman or Netanyahu will not continue to pursue policies, such as the de facto support for Russia’s war against Ukraine, that either violate U.S. interests or negate its values.

The United States’ reassessment of relations with Saudi Arabia, Israel, Turkey, and Egypt should take place in the context of reducing its military footprint in the region. There are U.S. troops deployed throughout the region, from Turkey and Syria, to Jordan, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Oman. This is in addition to the periodic flights of U.S. strategic bombers on roundtrip missions to the Persian Gulf, along with frequent deployments of aircraft carriers to the Arabian Sea.

Are large U.S. air bases really necessary in Kuwait, Qatar, and the UAE? The U.S. could defend its interests in the Gulf (namely, deterring Iran and terrorist groups in the region) by maintaining the crucial naval base at Bahrain, the headquarters of the U.S. Fifth Fleet, and supplementing it with more concentrated air power. This force can be further buttressed by aircraft carriers sailing in nearby waters. Before the string of recent wars in the Gulf, beginning with Iraq’s invasion of Iran in 1980, this was the non-overbearing way that American power was felt in the region. A wise Arab Gulf leader told an American diplomat at the time, “We want you to be like the wind, we want to feel you, but we don’t want to see you.” That was sound advice then and would be mostly sound advice now.

Once upon a time, there existed a great reservoir of good will in the Middle East toward the United States. America was seen by the people of the region as the educator that built the American University of Beirut (1866) and the American University in Cairo (1919), among other educational institutions from Turkey to the Gulf. America was hailed as the promoter of self-determination after World War I. America was the refuge of choice for the first wave of immigrants beginning in the late 1880s, fleeing the harsh conditions in Ottoman Syria (today’s Syria, Lebanon, and Palestine) and seeking the promise of freedom in the United States. Most importantly, America was a major Western power with no colonial legacy in the Middle East. America did not rule over Arabs and Muslims, unlike the European powers. The caption of a picture taken in 1878 of the Syrian family of the professor Yusif Arbili says it all: “here (at last) I am with the children exulting in freedom.”

That reservoir of good will began to dwindle with the growing U.S. support for repressive autocratic regimes in the quest to check local communists and the Soviet Union. America’s embrace of Israel following its conquest of more Arab lands during the 1967 Six-Day War deepened and widened the alienation of many Arabs from the U.S. Opinion polls throughout the region today confirm the negative views of U.S. policies in the Middle East and of America itself. Lowering Washington’s military profile and elevating its defense of human rights in a consistent, explicit, and universal fashion would go a long way toward restoring its credibility with the people of the region. It would also help them fend off autocracy, repression, and aggressive nationalism at home.

At a time when America’s democratic system of governance, its liberal open society, and its cherished concepts of inclusive patriotism and political pluralism are being challenged and eroded, it is folly to further undermine those values and the institutions that undergird them by seeking closer ties with indefensible regimes in the Middle East. Saudi Arabia, Israel, Turkey, and Egypt may be Washington’s traditional allies in the region, but they do not deserve that status today.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The U.S. policy on Myanmar is all wrong

#peace#Burma

NEW DELHI - U.S. President Joe Biden and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi recently issued a joint statement "expressing deep concern about the deteriorating situation in Myanmar" and calling for constructive dialogue to help the country transition to an inclusive federal democracy. Unfortunately, U.S.-led sanctions undermine this goal and make the situation worse.

Senegal’s elections and Africa’s future

RABAH AREZKI thinks what Bassirou Diomaye Faye's presidency could mean for one of Africa's most talked about democracies.

Western sanctions, while inflicting pain on ordinary Myanmar citizens, have left the ruling military elite relatively unscathed, leaving the military junta with no incentive to relax political control. The main beneficiary is China, which has been able to expand its foothold in a country it sees as a strategic gateway to the Indian Ocean and a vital source of natural resources.

This development has exacerbated regional security challenges. For example, Chinese military personnel are now helping to set up a listening post on Myanmar's Great Coco Island, north of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands where the Indian military's only tri-services command is located. Once operational, the new spy station is likely to assist China in its maritime surveillance of India, including monitoring the movements of nuclear submarines and tracking missile tests that often land in the Bay of Bengal.

To some extent, history is repeating itself. Starting in the late 1980s, previous U.S.-led sanctions paved the way for China to become Myanmar's main trading partner and investor. This sanctions regime lasted until 2012, when Obama announced a new US policy and became the first US president to visit Myanmar. In 2015, Myanmar elected its first civilian-led government, ending decades of military dictatorship.

However, in February 2021, the military staged a coup and detained civilian leaders including Aung San Suu Kyi, prompting the Biden administration to reimpose sweeping sanctions. Importantly, the reversal of Myanmar's democratic project was precipitated by earlier US targeted measures against the military leadership, including Commander-in-Chief Min Aung Hlaing, over human rights abuses against Rohingya Muslims that forced the majority Flee to Bangladesh. After President Trump's administration imposed sanctions on Min Aung Hlaing and other senior commanders in July 2019, the generals lost momentum to maintain Myanmar's democratization. A year and a half later, they overthrew the civilian government after denouncing the results of the November 2020 national election as fraudulent.

The lesson for Western policymakers should be clear. Separate sanctions on foreign officials—an essentially symbolic gesture—could severely hamper U.S. diplomacy and have unintended consequences. (Indeed, China has resisted direct military talks proposed by the Biden administration as a sign that the U.S.

The longstanding lack of contact between the United States and Myanmar’s nationalist military—the only functioning institution in a culturally and ethnically diverse society—is a chronic flaw in its Myanmar policy. Because of this limitation, Aung San Suu Kyi achieved near-saint status in the Western imagination, and the highly regarded Nobel Peace Prize winner came after she defended Myanmar's Rohingya policy against genocide charges. The reputation of the award winner plummeted.

With junta leaders under sanctions and civilian leaders in detention, the United States has few tools to influence political developments in Myanmar. Instead, the United States and its allies have tightened sanctions and supported armed resistance to military rule. To this end, the 2023 U.S. National Defense Authorization Act added a provision for Myanmar, authorizing the provision of "non-lethal assistance" to anti-regime armed groups, including the People's Defense Forces. People's Defense Forces This is a nominal army established by the shadow government of national unity. Biden now has considerable scope to help Myanmar's anti-junta insurgency, just as Obama provided "non-lethal assistance" in the form of battlefield support equipment to Ukrainian troops and Syrian rebels.