#Tusheti

Photo

“ Incredible sunset “ // alex stead

74 notes

·

View notes

Video

Lower Omalo, Tusheti by mikhail

Via Flickr:

Olympus OM-3ti, OM Zuiko 1.8/50, AGFA Optima Prestige 100 (expired 2007)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Caucasus Crossing - Tusheti

Tbilisi airport at 4:30 AM. Standing next next to luggage belt with a bunch of sleepy passengers, hoping my bike made it through the transfer in Riga.

My yellow bike box is easy to spot from afar. Half-asleep, I start pushing it towards arrivals hall. Despite the early hour, there are already several taxi drivers offering their services. My pre-arranged pickup from the hotel is nowhere to be…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Photo

The climb to Abano Pass, in Georgia is regarded as one of the most dangerous on Earth. Every autumn, a spectacular animal migration takes place in Georgia’s Tusheti region in the northern Caucasus Mountains. Radio Free Europe photographer Amos Chapple recently joined a group of shepherds and their dogs on what he refers to as a “deadly, boozy journey” from the steep mountains to the plains, as they brought their 1,200 sheep down to their winter pastures.

Amos Chapple

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Wild mountains of Tusheti. Georgia. [OC] [3040x1440]

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

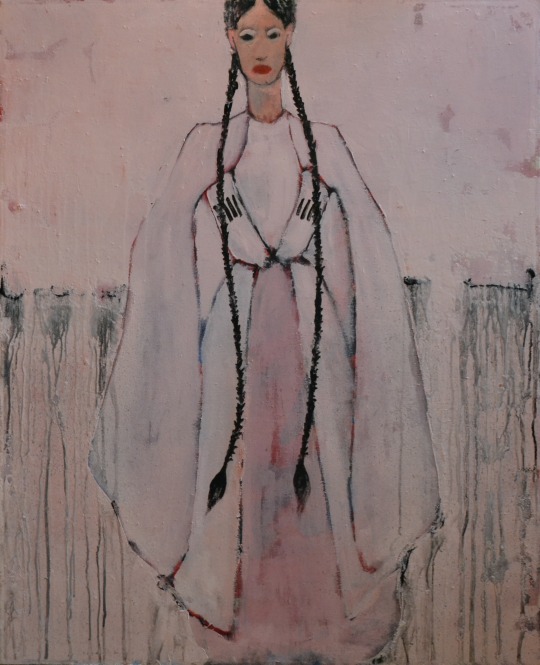

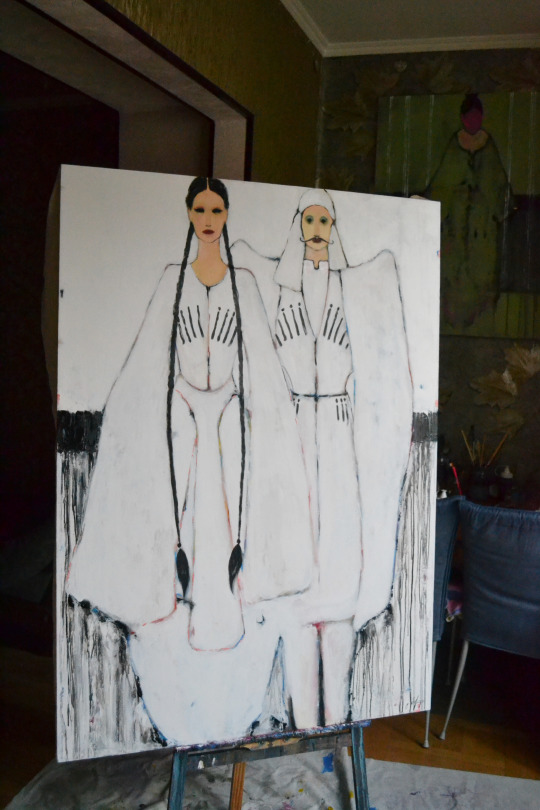

Georgian traditional clothing

The Roots series. Traditional clothing by Gela Mikava

Traditional lifestyles developed around the local climate and terrain, which in turn precipitated the creation of conventional clothing. Although every region of Georgia possessed its own distinct attire, an overarching similarity was seen in the chokha (Russian: cherkeska), a wool coat typically worn by men and noted for the cartridge holders sewn onto the chest. Women’s clothing was much more varied between the regions, particularly in the remote mountain communities.

Prince Vakhushti Batonishvili (1696–1757) paved the way in the study of traditional Georgian clothing, giving particular attention to the attire from medieval times and that of his own generation. Foreign travelers such as Arcangelo Lamberti and Jean Chardin also made notable contributions to the topic. The latter travelled to Georgia in the 1670s, and his remarkably detailed notes provide valuable insights into local clothing of that time as well as the similarities and differences between Persian, Georgian and European attire.

Thanks to these and other such historical records, a picture of traditional Georgian clothing from each region of the country may be pieced together today.

Traditional Clothing of Kartli-Kakheti

According to Vakhushti Batonishvili, people from Kakheti and Kartli had similar clothing styles. For men in Kartli-Kakheti, the primary piece of apparel was the chokha. The Kartli-Kakheti chokha was longer than that of neighboring Khevsureti and had a triangular opening at the neck to reveal an inner cloth. The chokha, worn without a belt by men, included a slitted skirt and miniature pockets on either side of the chest that were traditionally loaded with bullets. The Kartli-Kakheti chokha was usually tan, blue, black or red in color.

In keeping with conservative Georgian culture at that time, women in Kartli-Kakheti wore long dresses with beautiful ornate bodices. The dress was tightened at the waist with a richly decorated belt that draped almost to the end of the skirt. The most important aspect of the outfit was the headdress, which was defined by a triangular white veil of tulle, a velvet rim and a dark headscarf.

Traditional Clothing of Pshav-Khevsureti

Clothing in Georgia’s mountain regions was made of a durable wool fabric that provided protection against harsh alpine conditions. Despite its practical nature, the apparel was always beautifully decorated, as women in Pshav-Kvevsureti were trained from childhood in wool processing and dyeing.

Kvevsureti’s chokha, known as talavari, were short with slits running down to the waist and a beautifully decorated fabric affixed to the front. Men’s outfits typically consisted of knitted pants called pachichebi, woven fiber shoes known as tatebi and chokha with colorful religious symbols embroidered on the front.

Traditional women’s dresses in Khevsureti were called sadiatso. Sadiatso were knee-length dresses decorated with baubles and sophisticated geometric patchwork. Just like their Kartli-Kakhetian neighbors, women in Khevsureti wore a headdress. Traditional Khevsur headdresses were greatly admired and decorated with cross-shaped ornamental patterns. Pshav and Khevsur women would also wear silver coins and cross necklaces.

Traditional Clothing of Tusheti

Tusheti’s highland inhabitants were known for their use of wool in making clothes, shoes and rugs, with solar symbols and crosses regularly employed in their remarkable clothing and jewelry designs.

Both women and men in Tusheti wore colorfully knitted shoes called chitebi. Men’s chitebi were plainer with polka dots, while women’s chitebi were striped and multicolored. When making chitebi, the weaver would start from the tip of the shoe and continue backwards towards the heel. Chitebi shoes also played a role in local superstition: On a Wednesday during Lent, mothers would put male chitebi under the pillow of their daughters right before they went to sleep, in the hope that they would see their future husband in their dreams.

Traditionally, a Tushetian woman wore a black headscarf which reached down to her knees, a loose-fitting dress underneath her robe and an outer garment adorned with jewelry across the chest. Men’s clothing consisted of a chokha and a warm black hat.

Traditional Clothing of Svaneti

No discussion of Georgian traditional clothing would be complete without mentioning Svaneti’s famous hats. Svan hats were usually gray with black seams. Each hat was made from 200 grams of sheep’s’ wool and took about 30 hours to complete. The black seams were cross-shaped and reflected the popular Svan greeting , “May the cross protect you”. Svan hats were valued for providing warmth from winter’s chill and respite from summer heat.

Traditional Svan clothing consisted of a shirt, chokha, trousers and Svan hat. Women wore a woolen dress and headdress adorned with earrings and jewelry, while those who were wealthy also wore silk shirts and a velvet cloak.

Traditional Clothing of Racha

Iakob Gogebashvili, a leading 19th-century Georgian pedagogue, described female outfits from Racha in one of his writings, noting that they wore the chokha and an akhalukhi undershirt.

Women’s clothing from Racha also attracted the attention of many foreign travelers. In 1874, German scientist Dr. W. B. Pfaff could not hide his astonishment towards women’s clothing in Racha, exclaiming “I was amazed by the variety of women’s clothing, which in many ways reminds me of Anatolia”. In 1874, English explorer Philip Grove, upon seeing three local women, also noted “They wore short dresses and trousers…with grace”.

Apparently men’s attire in Racha was less noteworthy, as little information has reached us today regarding their traditional style of dress.

Traditional Clothing of Adjara and Guria

Traditional Georgian men’s clothing in the western Adjara and Guria provinces differed dramatically from that of eastern Georgia. The typical men’s outfit in Guria-Adjara, Samegrelo and the whole of southwest Georgia was the chakura, which consisted of a short waist-length chokha, wide-brimmed trousers and a colorful silk belt.

Throughout the ages, women in Adjara have worn three types of dresses. Zubun-faraga, the oldest of the three, derived its name from the Turkish word zubuni, meaning “coat”. The dress was long and hemmed in at the waist, with special attention paid to lavish embellishments on the bodice. A zubun-faraga dress can be seen today on display at the Simon Janashia Museum in Tbilisi.

The zubun-faraga dress was gradually replaced by the datexili dress, which was recognizable by its long, wrinkled appearance and multicolored threads worked into the fabric. It was tightly fitted to the body and had hidden pockets sewn into the wrinkles. In later years, the datexili dress evolved into a new variation known as the forka dress.

Traditional Georgian Shoes

Traditional Georgian shoes were typically made using muted colors of black, red, green and light brown. The 17th-18th century Georgian diplomat Sulkhan-Saba Orbeliani mentions several types of local shoes in his writings:

Tsugha were worn at home by both men and women. They were sewn from leather of various colors and the edges beautifully decorated.

Kalamani were common leather shoes worn by villagers beginning in the 10th-11th centuries.

Mogvi were tall leather boots worn by kings and nobles.

Additional Information

The best places to see Georgian traditional clothing today are at the Art Palace of Georgia (formerly known as the Museum of Cultural History) and at the Simon Janashia Museum, both located in Tbilisi. Traditional clothing, which has slowly been making a comeback in the 21st century, is also sometimes donned at Georgian traditional weddings and cultural events.

The Day of National Dress in Georgia is a recently established holiday celebrated on the 18th of May. In commemoration of their heritage, Georgian dancers and ordinary people alike dress in national costumes and march across the city to demonstrate the beauty of traditional Georgian attire. If you are visiting Georgia during this time, be sure to join the celebration to become familiar with diverse costumes from every region of Georgia!

1 note

·

View note

Text

Irakli Khvedaguridze, 80, is the only licensed doctor across nearly 386 square miles of mountainous land in the Tusheti region of northeast Georgia. Here he rides his white horse, Bichola, through the village of Omalo. In the background is the clinic where he obtains limited medical supplies.

This Doctor Braves Mountains By Horseback and On Foot To Make House Calls

This 80-year-old physician is a lifeline during brutal winters in the Caucasus Mountains.

— Photographs By Tomer Ifrah | By Nadia Beard | March 16, 2022

TUSHETI, GEORGIA — During the summer and early autumn, before heavy snow blankets the mountain peaks, Irakli Khvedaguridze gets to his patients on his white horse, Bichola. Later in the season, when the snow reaches too high for the horse to gallop, Khvedaguridze converts his shoes into skis, using a pair of sanded birch planks nailed with wide canvas. Once the snow rises above his knees, he can only travel on foot.

Regardless of the elements, he never visits a patient without first packing a knife, a box of matches, food that will last for at least two days, and a hunting rifle—along with his stethoscope and other medical supplies. Such is the life of this 80-year-old mountain doctor.

Top: Region Map. Bottom Left: Irakli Khvedaguridze relies on his horse, Bichola, to visit patients and travel through the mountain villages of Tusheti, Georgia. He serves as a lifeline for the dwindling community of Tush people who remain in this remote area throughout the eight months of winter. Bottom Right: A view of Bochorna, a village of a dozen houses high above Tusheti’s pine-filled Gometsari gorge. Come winter, nearly all of the Tush people head to the lowlands.

“Each time you step out, no matter the season or weather, you know that anything could happen,” says Khvedaguridze, a muscular man with milky blue eyes and a shock of white hair that protrudes from underneath a navy-blue baseball cap he is rarely seen without. “You might fall off a cliff, injure something. This is wild nature.”

Top: Early morning clouds hover over the village of Omalo in Tusheti, Georgia. Bottom: Snow covers part of the land in the village of Borchorna.

Khvedaguridze, the only licensed doctor across nearly 386 square miles of mountainous land in this historic region in northeast Georgia, serves as a lifeline for the dwindling community of Tush people who remain in this remote area throughout the eight months of winter.

Top: Irakli Khvedaguridze tends to a shepherd, Rezo Partenishvili, who was experiencing agonizing back spasms, stomach cramps, and other ailments. Khvedaguridze gave him a packet of pink pills to take with meals and an injection to relieve the pain. Bottom Left: A patient suffering from alcohol poisoning is transported via helicopter to a hospital in Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia. Bottom Right: Irakli Khvedaguridze escorts a patient aboard a helicopter en route to the hospital.

A few years ago, an intoxicated patient in the village of Omalo had to be airlifted to a hospital in the lowlands of Kakheti after he accidentally shot himself in the stomach with a hunting rifle. In the early 2000s, Khvedaguridze saved a boy’s leg after he trod on an unexploded mine.

More frequently, he tends to common ailments: shepherds with back pain, aging locals complaining of heartburn, or tourists who get into accidents. One summer, a Czech visitor was mauled by shepherd dogs while hiking. Another year, an American got sick from drinking water out of a stream.

Top: Irakli Khvedaguridze, outside the clinic in Omalo, prepares his horse for the ride back to his home about six miles away in the village of Bochorna. Bottom Left: A mountaintop view outside the village of Bochorna in Tusheti, Georgia. Bottom Right: During the coldest winter days in Tusheti, temperatures can drop down to way below freezing.

Top: Irakli Khvedaguridze travels through the Tusheti region on his horse, Bichola. Bottom Left: During a medical excursion in August, Irakli Khvedaguridze made his way over the mountain to reach the home of an ailing shepherd. Bottom Right: Irakli Khvedaguridze looks through binoculars over the Tusheti mountains. “My father, my grandfather, all my ancestors were born here,” he says. “This area belonged to us.”

In December, while paying a visit to his friend at a hamlet in a gorge dotted with a few wooden houses and a sheep pen, Khvedaguridze received a call from Georgia’s 112 emergency services about a man in another village complaining of a racing heartbeat and chest pains. He made the 7.5-mile trek by foot to reach the patient.

The next day, when the helicopter landed on the snow-laced pastureland of Kvavlo, the patient was lying face up on the ground. The tall, thin man in his early 40s was so inebriated his legs buckled as he was loaded onto the helicopter for transport to the hospital. Khvedaguridze also climbed aboard the flight to monitor and escort the patient to the hospital. The patient was released a few days later, and returned to his village. But alcohol poisoning sent him back to the hospital in January.

The Doctor’s Journey

In 1941, the year Khvedaguridze was born, sheep-keeping was the lifeblood of Tusheti. The twice-yearly transhumance—shepherds migrating their flock on foot down to the lowland pastures for the winter and back up to the highlands for grazing in the spring—was just another event in the Tush calendar.

Top: Irakli Khvedaguridze stands for a portrait. He is the only licensed doctor across nearly 386 square miles of mountainous land in this historic region in northeast Georgia. Bottom: Irakli Khvedaguridze, who keeps his limited medical supplies—a stethoscope, pain killers, a suturing kit, injections for muscle spasm relief—in a German-made military first aid case emblazoned with a red cross, describes his profession as a "mediation between God and the sick."

Today, it signals the near-total departure of the Tush people to the lowlands for the winter, and their return when the Abano Pass—comprising winding, narrow, cliffside roads—reopens in spring.

Khvedaguridze lives in Bochorna, a village of a dozen houses high above Tusheti’s pine-filled Gometsari gorge. His two-story cottage is made from thin grey-brown slate and wood, and overlooks the wide, green valley. On the steep hillside below, some houses with rusted metal roofs speckle the grass beside the remains of stone towers long destroyed.

With his horse, Bichola, at his side, Irakli Khvedaguridze, walks down the steep descent en route to the home of a patient several miles away. To save time, the doctor chose to ride through winding mountain paths.

“My father, my grandfather, all my ancestors were born here,” Khvedaguridze says. “This area belonged to us.”

After graduating from the Medical Institute of Georgia (now called the Tbilisi State Medical University) in 1970, Khvedaguridze took his first job at a hospital in central Georgia. When the previous mountain doctor left Tusheti in 1979, he did one-month rotations there a couple of times a year. In 2009, he left his job as a neuropathologist at a hospital in Alvani, and the next year, instead of retiring, he took on the permanent post in Tusheti.

Khvedaguridze, who keeps his limited medical supplies—a stethoscope, pain killers, a suturing kit, injections for muscle spasm relief—in a German-made military first aid case emblazoned with a red cross, describes his profession as a “mediation between God and the sick.”

“For me, there’s no night or day,” he says. “If they call me to help someone, no matter the circumstances, no matter the rain, snow, day or night, I have to go. Even if I’m as old as 90, should there be people who need me, I will go to help them. It’s my duty.”

Mountain Doctor Treatments

Khvedaguridze’s 59-year-old neighbor, Elza Ivachidze, is among his patients. When she complained of shortness of breath and pain in her arm last summer, Khvedaguridze treated the symptoms with pain killers and an injection.

“He often gives old, traditional treatments, including herb teas and pears. It’s not always pills and antibiotics,” says Ivachidze, adding that she worries about what will happen once Khvedaguridze is gone. “He’s the oldest and wisest person we have. Who would replace him?”

During another medical excursion in August, Khvedaguridze saddled up Bichola to make his way over the mountain to reach the home of a shepherd, Rezo Partenishvili, who was experiencing agonizing back spasms for the third day and could not stand up, let alone walk his sheep onto the mountain for grazing.

On the descent an hour later, Khvedaguridze dismounted and soon three snarling Caucasian shepherd dogs alerted him that he was close to his destination. With the speed of someone a quarter his age, he dropped to the ground to snatch a handful of rocks to scare off the dogs but ultimately did not need to throw them.

At the sheep pen, Partenishvili, 39, was lying on a mattress of folded woolen blankets known as nabadi. He is one of five shepherds who graze the flock across the mountain. None of the others looked worried. Back pain, they say, is the most common ailment among shepherds. At this time of the season, they spend their days bent over, shearing the sheep.

In addition to back spasms, Partenishvili suffered from stomach cramps, diarrhea, and chronic sciatica. Khvedaguridze gave him a packet of pink pills to take with meals, then retrieved an injection with some red liquid from his bag: indomethacin to relieve the pain. Partenishvili muttered that he didn’t want it.

“Really? You’re telling me you’re afraid of such a small thing?” Khvedaguridze jested. He reminded Partenishvili that the other option was to stay in bed for a month unable to work. Partenishvili rolled over and pulled down his trousers for the shot.

As Khvedaguridze prepared to head back home, a man sitting nearby quietly puffing on cigarettes called out to complain about shortness of breath. “Get that cigarette out your mouth, then!” Khvedaguridze replied. The shepherd laughed but obeyed, throwing what was left of the cigarette into the fire pit in front of him.

Uncertain Future

Toward the end of the year, with the road now closed for two months, the mountain doctor’s birthplace is almost empty of both people and animals. The transhumance in October cleared the region of most sheep and their shepherds. Only one small flock grazed on a distant hill, and an old Jeep puffed out thick grey fumes before disappearing into the distance.

The arrival of snow quickly revealed the paucity of Tusheti’s infrastructure. Moving around demands sustained physical strength. Fetching water from the nearest tap or spring can take half the morning. With nowhere to get fuel, car journeys must be rationed. Military helicopters are used to deliver food and other necessities. Relatives in the lowlands prepare care packages for soldiers to deliver to family members up the mountains.

Loneliness can creep in from the isolation. “Sometimes I hear a wolf from afar,” he says. “That’s how I know there’s life out there somewhere.

An easier life would be possible elsewhere, but leaving Tusheti would sever Khvedaguridze’s connection to his ancestors’ land—and to his patients.

Despite his devotion, the day eventually will come when he can no longer handle it here. “I will leave,” Khvedaguridze says. “I don’t know if the next doctor will risk their life for this.”

0 notes

Photo

The Stark Beauty of Tushetian Shepherds’ Journey Across Georgia’s Caucasus Mountains

As spring begins to melt the snow in the mountains of northeastern Georgia, shepherds drive thousands of sheep across a perilous mountain pass to the stunning meadows of the Tusheti highlands. The meadows of the Tusheti have been called the last wild place in Europe and make for ideal summer grazing for the hardy, local sheep of the region—but the steep path is full of dangers, dangers that can sometimes prove fatal. Herding livestock to seasonal grazing grounds, a practice known as transhumance, is nothing new. Evidence of such journeys stretches back 10,000 years to when animals were first domesticated. The Tusheti shepherds of Georgia have moved their herds between seasonal pastures for at least half a millennium. Nestled in the Caucasus Mountains, the grassy fields of the Tusheti make ideal summer pastures for the hardy local sheep. Between June and September, the animals munch on high-protein grasses such as alpine bluegrass and toothed bellflower, giving the cheese made from the sheep’s prized milk its unique, strong flavor. In 2019, the gourmet cheese, known as Tushetian or Tushuri guda after the sheepskin, or guda, used in curing, earned a coveted appellation of origin, which verifies that cheese from the region is the real deal. In spring 2022, the Philippe Brothers, a documentary team made up of brothers François, Stéphane, and Michael Philippe, followed along as one group of shepherds made their way up the dangerous trail to the Tusheti. Shepherds are usually related, and the group of four shepherds they followed were all kin and grew up surrounded by the stunning mountain vistas of the region. In 2022, the four shepherds (who preferred not to share their names) set out on their annual trek with 1,200 sheep and eight herding dogs. “The scenery was epic but ruthless,” says Michael Philippe. “It was not a place to live in, yet we walked there for two days with them, alone in pure wilderness.” Days started early with the group easily covering more than 30 miles in a day. Food was basic, says Philippe. A quick lunch might consist of bread, a can of food, like stewed fish, and “lots of alcohol.” Often the shepherds downed shots of chacha, a strong, Georgian liquor made from the leftovers of wine production. At night, they bundled up in their jackets and slept outside on the cold mountainside. Along the way, the group had to cross several raging, freezing rivers—Philippe sometimes opted to take off his shoes and carry them. Wet shoes were worse than freezing feet. But by far the riskiest stretch of the journey was the Abano Pass, says Philippe. The unpaved, 43-mile stretch of road weaves across the Caucasus Mountains at an elevation of almost 10,000 feet. The unpredictable spring weather can cause sudden snow storms, rock slides, and dense fog. Snowmelt from the mountains destroys portions of the pass every year. “All the journey was difficult but the pass was the worst,” says Philippe. “We could [have] died many times because of the state of the road, falling rocks.” Once the shepherds made it to the Tusheti mountain valleys, they settled back into familiar rhythms—milking and tending to the sheep by day and then gathering around the fire to share songs and stories by night. Tusheti villages, abandoned for most of the year, come back to life in summer as entire communities return to their mountain homes. Despite climate change and natural disasters threatening their way of life, every year shepherds continue to make the difficult journey to and from the mountains. The Philippe brothers took these images of the transhumance, revealing the shepherds’ determination and triumph in completing the dangerous journey for yet another year.

https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/transhumance-tusheti-georgia-shepherds

0 notes

Text

Summit of Georgia; Original Occupation of Villagers Still Using Simple Rock Equipment.

Summit of Georgia; Original Occupation of Villagers Still Using Simple Rock Equipment.

Summit of Georgia; Original Occupation of Villagers Still Using Simple Rock Equipment. – Travel Ideas

Europe is one of the points in the world that are many nature, travel destinations being interesting and amazing. One of the most beautiful places in Europe is the summit of Mount Georgia, precisely in the Tusheti region. The summit of Georgia is the original dwelling of the villagers who still…

View On WordPress

#best places to live#cabin rentals#georgia mountains#georgia mountains cabins#georgia mountains map#list of georgia mountains#mountains europa#north georgia mountains

0 notes

Video

Abano Pass II by mikhail

Via Flickr:

The road to Tusheti, also known as Abano Pass, is regarded as one of the most dangerous roads in the world (by BBC). Olympus OM-3ti, OM Zuiko 35/2, AGFA RSX II 100 (expired 2007). No post processing of any kind.

1 note

·

View note

Text

オープンスタジオ2207

オープンスタジオのお知らせ

スタジオ・ツキミソウ OPEN STUDIO 2211

2022年7月28日(土) 12:00 -17:00

Mariam Kalandadze (from Georgia) painter, installation

斉藤 真人 画家

DIAMONDS ARE FOREVERメンバー 異性装の日本史(松濤美術館)予告

Mariam Kalandadze (from Georgia)

Born 21 November 1994 in Tbilisi, Georgia 35 Polikarpe Kakabadze str. Tbilisi,Georgia

[email protected] +995577525658

Education

2014 - 2015 Prép’art Paris, France

2015 - 2018 l’Ecole nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts Paris, France

Working Experience

2017 Artist in recidency “AqTushetii” Tusheti, Georgia

2018 Bronze Foundry internship at “Foundation De Coubertin” Saint-Rémy-lès-Chevreuse, France 2018- present Creating Cultural, Agricultural & Educational land “VELI” Bakurtsikhe, Georgia 2019 - present Set designer at Theatrical company “Haraki” Tbilisi, Georgia

Solo Shows

2016 “Fifth Element” Beaux arts de Paris, France 2017 “Part One” Kardanakhi, Georgia

2021 “Nakadi” Tbilisi, Georgia

Group Shows

2017“AqTushetii” Omalo,Georgia

2019 “Oxygen no fair” Tbilisi, Georgia 2019 “Rivers magic garden” Tbilisi, Georgia 2020 “Clean Hands” Tbilisi, Georgia

0 notes

Photo

Tusheti - Omalo ------------------------------ ომალო - თუშეთი (bij ომალო , თუშეთი) https://www.instagram.com/p/CkLvdlmoa_R/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes