#Stadium Community Inclusion Task Force

Text

Can we give a round of applause to the Buffalo Stadium Community Inclusion Task Force?

Last year, the state of New York agreed to give $850 million taxpayer dollars to the Buffalo Bills to build a $1.7 billion dollar stadium. Because New York taxpayers are giving so much to this project, rules were put in place that stated when the stadium was being built, “36% of construction contracts” were to be given to businesses owned by minorities, women, and service disabled veterans. When…

View On WordPress

#April Baskins#Black Chamber of Commerce#Buffalo Bills#Buffalo News#Community Benefits Oversight Committee#Construction#Construction Contract#Erie County#Erie County Legislator#Gilbane Turner#Independent Contractors Guild of WNY#NAACP#New York#NFL#Stadium Community Inclusion Task Force#Task Force#WIVB

0 notes

Link

...This was the last day of the year for the class of 2018 at Glenelg High School. There was going to be an awards ceremony, a picnic, that end-of-a-journey feeling that always made [principal David Burton] so proud of his job. But as he was on his way to work at 6:25 a.m., the assistant principal had called, agitated and yelling about graffiti...

...Beneath his dress shoes, there were more swastikas. Spray painted around them were crude drawings of penises.

Then Burton saw the letters “KKK.” He saw the word “Fuck” again and again next to the words “Jews,” “Fags,” “Nigs” and “Burton.”

He kept walking, following the graffiti around the building’s perimeter. It was on the sidewalks, the trash cans, the loading dock, the stadium around back. There were more than 100 markings in total, though he didn’t bother to count.

He turned a corner and saw something written in large capital letters on the sidewalk: “BURTON IS A NIGGER.”

...A quarter of all hate crimes reported to the FBI, more than any other category, are similar to the attack discovered at Glenelg on May 24, 2018. Vandalism and destruction of property, a physical marking of an age-old threat: You don’t belong here.

...In one of those homes, 72-year-old Susan Sands-Joseph was watching. She knew Glenelg well. She was one of the first black students to attend the school after desegregation. Suddenly, all the memories that she tried not to dwell on were dredged up again: the words she was called, the tomatoes thrown at her head, the looks her parents gave her when she came home saying scalding hot soup had been pushed into her lap again. “It’s okay,” she had promised them. “I’m fine.”

...Panicked, [Seth Taylor, one of the vandals,] started Googling:

“How long do you go to jail for vandalism?”

And then: “Can you get a hate crime for painting swastikas?”

...He had already begun to separate what he’d done from who he believed himself to be. He hadn’t intended to hurt anyone, he said. He would always maintain he wasn’t an anti-Semite, a homophobe or a racist.

...At 11:35 p.m. on May 23, the students’ IDs began auto-connecting to the WiFi. It took only a few clicks to find out exactly who was beneath those T-shirt masks.

“You have the right to remain silent,” an officer said to Seth before long. “Anything you say or do . . . ”

They told him to remove his graduation cap and gown. They cuffed his arms behind his back.

Seth realized they were about to march him outside, past the windows of the cafeteria. By now it would be filled with students eating lunch.

“Can you cover my face so that the kids don’t videotape me?” he asked.

“No,” an officer replied. “You deserve this.”

...Most are unaware of the history that came before Columbia [a planned community founded on the principles of integration and inclusion in Howard County]. ... An estimated 2,800 people were enslaved in the county at the beginning of the Civil War. A century later, when the Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 that schools must be desegregated, Howard County was so resistant that it took more than a decade for the black-only school, Harriet Tubman, to close its doors. The opposition to black students learning alongside white ones was so fierce, a cross was burned. It happened outside a school dance at Glenelg High School.

...Among black families like [Tyler Hebron’s], there were doubts that the white teens would face the kind of punishment black teens receive for similar crimes. Two years earlier, a group of students had painted swastikas on a historic black schoolhouse in Northern Virginia. A Loudoun County judge sentenced them not to jail time or community service, but to reading: along with visiting the Holocaust museum, each had to choose a single book about Nazi Germany or the Jim Crow era and write a report on it.

...Two of [the vandals] had tried to have the hate-crime charges dismissed. Their attorneys claimed that their First Amendment rights were being violated. They could be punished for the vandalism, the argument went, but not for what they wrote.

It didn’t work.

Now, it was [Judge William V. Tucker’s] job to answer a question the community had been debating for nearly a year: What consequences did these young men, now 19, deserve?

...Seth said he just wanted all of them to understand: He is not a racist.

Later, he would explain himself this way: “I never really understood the symbol of the swastika. I knew it was wrong to plaster it somewhere. I didn’t learn exactly what [the Nazis] were doing to the Jews until I went to the Holocaust Museum. I never learned that they were mutilated. I knew that they were, like, burned. But I never learned that they had experiments done on them, were injected with diseases. The school didn’t include that. They just included the burning and the train cars.”

His understanding of the KKK was limited, too, he said. “Some people think it’s just a word, or a symbol or three letters put together. . . . But they were lynching people, hurting people for no good reason.”

...“I spray paint one racist thing and, suddenly, I become a racist? Just because I did it doesn’t mean I hate Jews, gay people or black people.”

He was standing before the judge, pleading guilty to a hate crime, but he would not admit that he harbored any hate.

...Behind her, Principal Burton was listening. He’d heard Joshua Shaffer’s attorney give a similar speech. When Matthew Lipp was sentenced, he would hear it then too. Tyler Curtiss had written it in a Facebook apology the day after the crime...

They all believed it was possible to do what they did without really meaning it.

Burton wanted to look them in the eye and say: “You did something very racist. How you don’t think you’re a racist, I don’t know.”

...He believed what possessed them to draw those words and symbols that night wasn’t a lack of knowledge, but something deeper, something ugly, something taught to them, consciously or unconsciously, along the way. If they couldn’t admit that now, maybe they never would. But it wasn’t his responsibility to educate them any more.

When it was Burton’s turn to speak at Seth’s sentencing, he didn’t say the word “racism.” He talked about all the people the crime had affected — the teachers crying in his office, the parents who pulled their kids out of his school, his daughter in tears, and for just a few moments, himself: “I know I give up my time, my effort, I give up my life for my students,” he said. “I think the only thing I am asking in return is just a little bit of respect.”

...[Burton] had to focus [this year] on his 1,200 current students: the LGBTQ kids who still felt isolated. The Jewish girl who told the local paper she still wishes she could transfer. Whoever was still scrawling swastikas on the bathroom stalls.

In the past year, he’d created a task force of diverse students to work on the school’s climate. Soon every freshman would go through an empathy workshop. And nearly 40 of his employees had spent the year meeting to discuss the book “Waking Up White,” a memoir of a white woman who comes to understand that racism is a system that she had been shaped by and contributed to her entire life without even realizing it. Maybe, he thought, that lesson would get passed on to Glenelg’s students...

[Read Jessica Contrera’s full piece at The Washington Post]

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Debate About Sports Activism Is Over – The Time Is Now

As we begin 2021, David Alexander, Managing Director of Calacus PR, looks at how the issue of sports activism altered over the past 12 months, and what is in store for 2021 as it continues to rise ahead of major events this summer.

There’s little doubt that 2020 was a difficult year for us all.

Sport suffered significantly due to lockdowns that have hindered competition, spectators attending in person and grassroots sport that means so much to so many.

But with more time on their hands, sports stars have been showing why the debate about sport and politics and sport and social good is essentially redundant.

If you go back in history, there are many instances of sports stars using their platform to make a political point.

“With more time on their hands, sports stars have been showing why the debate about sport and politics and sport and social good is essentially redundant.”

Muhammad Ali protested about the draft and refused to fight in the Vietnam war. That lost him his boxing licence and some of his peak years.

African-American athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised a black-gloved fist during the playing of the US national anthem, “The Star-Spangled Banner” during their medal ceremony in the Olympic Stadium in Mexico City in 1968.

And in more recent years we’ve had NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick take the knee to protest at inequality and police brutality in the United States.

Over in England, Manchester City and England forward Raheem Sterling has been vocal about racism in the game after both fans and media have targeted him.

“First and foremost, I don’t really think about my job when things like this happen. I think about what is right,” he said when discussing racism in the game.

In light of the death of George Floyd in the United States, footballers have been taking the knee before most top-level matches, to highlight the importance of diversity and equality in society.

England captain Harry Kane explained why it is so important that the ritual is continued: “We are a huge platform to share our voices across the world,” he said.

“I hear people talking about taking the knee and whether we should still be doing it and for me I think we should. Education is the biggest thing we can do to teach generations what it means to be together and help each other no matter what your race.”

Fellow England forward Marcus Rashford has also been in the news for all the right reasons, somehow managing to help Manchester United on the pitch while changing UK government policy off it.

Rashford has opened up about the struggles his family endured, relying on free school meals, breakfast and after-school clubs, food banks and vouchers to ensure he could eat.

He addressed the issue of children missing out on a free school meal during the UK’s coronavirus lockdown, which saw the government make a U-turn and make the vouchers available.

He then partnered with Fareshare to ensure food that would otherwise be wasted was redistributed to good causes and in early September, Rashford went even further, creating the Child Poverty Task Force with the food industry to shed light on the issue of child food poverty in the UK. No wonder he was awarded an MBE.

France and Barcelona forward Antoine Griezmann also took a stand against electronics brand Huawei, after reports emerged that the company was developing facial recognition software to be used on Muslim Uighurs in China.

“I take this opportunity to invite Huawei to not just deny these accusations but to take concrete actions as quickly as possible to condemn this mass repression, and to use its influence to contribute to the respect of human and women’s rights in society,” said Griezmann in a statement.

“When sports stars, clubs or federations work with brands, particularly these days, there needs to be constant dialogue.”

Huawei responded that they would like to speak to Griezmann, which begs the question why these discussions were not had between Griezmann or his representatives and Huawei before he cut ties.

Griezmann’s resignation as an ambassador will make the news, but if he HAD spoken with the electronics brand, he could have potentially worked with them to ensure better treatment of Uighurs.

When sports stars, clubs or federations work with brands, particularly these days, there needs to be constant dialogue.

Aligning yourself with a brand just because of a logo or free merchandise is not enough these days – and there is a lot of research that suggests consumers want their brands to make a positive difference.

But we have seen this year that sports stars feel more empowered than ever to try and make a positive difference, using social media to communicate which gives them a huge reach on channels that THEY own and so avoiding any misinterpretation or sensationalism that may have come from sending out a press release or staging a press conference, for instance.

As we move into the new year, the Tokyo Olympic Games this summer will be fascinating and provide a strong indicator for future trends.

“Calls have increased this year for a change to Rule 50 of the Olympic Charter, which bans any form of political protest during the Games.”

Rule 50 of the Olympic Charter states that the field of play and medal events should be ‘separate from political, religious or any other type of interference’ but it has been criticised recently, with new independent body the Athletics Association saying it is not fit for purpose.

Calls have increased this year for a change to Rule 50 of the Olympic Charter, which bans any form of political protest during the Games.

World Athletics have, for instance, said that athletes should have the right to make gestures of political protest during the Games, contrary to official IOC policy.

IOC President Thomas Bach has said that the Rule will be reviewed but more recently has said that “Inclusiveness and mutual respect also by being politically neutral” is also important.

The Games are supposed to be unifying so it will be fascinating to see who protests if Rule 50 remains in place.

To read the original article, please click HERE

#Harry Kane#Marcus Rashford#IOC#Thomas Bach#Olympic Games#Huawei#Barcelona FC#England football#Raheem Sterling#Muhammad Ali#Manchester City#Manchester United

1 note

·

View note

Text

How the Globalisation of football can create forms of racial social exclusion?

Football is presented as a huge global phenomenon due to the process of globalisation, however the process can present forms of social exclusion. Globalisation is a term which many scholars have struggled to define. Miller et al. (2001) explains globalisation is a difficult, continuous word meaning different things to different people. From a sociological perspective, Globalization includes social structural and cultural changes reflecting the growing interdependence and increasing interaction between individuals and organisations in space and time in order to form social order (Goldthorpe, 2002). When exploring globalisation, there is a need to be aware of the difference between the process and its outcomes (Houlihan, 2003). The outcomes of globalisation in sport can present many forms of social exclusion, which is interesting as ‘sport is increasingly recognized as a means for promoting social inclusion’ (Liu, p.1 2009). Social exclusion is defined as ‘an inability to participate effectively in economical, social, political and cultural life, alienation and distance from the mainstream society’ (Levitas, p.365, 2000). Forms of social exclusion, such as racial exclusion can be seen at a global level across sports including football.

This essay examines the globalisation of football and the effect the process has had on racial social exclusion. The essay starts by exploring globalization in football, social exclusion and race/racism. The potential reasons as to why racial social exclusion is presented in the global age of football are mapped out and analysed. A case study that encapsulates forms of racial social exclusion in football on the global scale is examined to provide evidence to determine how the globalization of football can create forms of racial social exclusion.

Globalisation of football

Football has long been one of the most popular sports across the world, which has developed the sport into a global process. This process is otherwise known as globalisation. Close and Askew (2004) explain globalisation is a collection of processes that promote increased global flows such as industry, investment, individuals and information. Furthermore, Hargreaves (2002) explains the globalisation of football presents great variation as it acts as the product of interaction between independent economic, political and cultural forces. The cycle of globalisation in football is demonstrated by the World Cup, the biggest international football event that draws millions of foreign fans, is televised around the world for a whole month and includes more than 200 national teams vying for the same award (Washington, 2010).

International competitions such as the world cup present many global flows. One global flow is ethnoscapes - the global flow of people (Appadurai’s 1996). In football this sees the transfer of individuals to foreign clubs or in football competitions such as European champions league where the best players drawn from Europe, South America and Africa perform all around Europe (Maguire, 2000). This sees players performing away from home in unfamiliar surroundings for the public’s entertainment. New surroundings involve different cultures, religions and beliefs. This is otherwise known as the ideoscapes global flow, which focuses on values that are centrally associated with state or counterstate ideologies and movements (Maguire, 2000). Giulianotti and Robertson (2004) explain globalization is marked culturally by processes of ‘glocalization’, whereby local cultures adapt and redefine any global cultural product to suit their particular needs, beliefs and customs. Glocalization suggests, international competitions and foreign players are usually welcomed, however what happens when they are not welcomed?

Social exclusion

Sport is a social configuration that enhances social inclusion by promoting tolerance, respect for others, cooperation, loyalty, friendship, and values of fair play (Marivoet, 2014). The globalization of sport looks to further promote social inclusion by turning the world into a single place where there is a sense of togetherness, unity and equity (Robertson, 1992). In many ways, this is true with the spread of sports throughout the world and the diversity in athletes’ origins participating in many of the professional leagues around the world (Thibault, 2009). However, in some cases, the globalization of football creates the opposite. Social exclusion is a widespread and pain fully felt feature of contemporary life conditions that encompasses economic, social, political and cultural dimensions (Spaaij, Magee and Jeanes, 2014). Tacon (2007) explain social exclusion refers to the multiple and changing factors resulting in people being excluded from the normal exchanges, practices and rights of modern society. Social exclusion has transformed into a seemingly permanent problem where the worlds ‘losers’ are separated from the ‘winners’ (Spaaij, Magee and Jeanes, 2014). But who decides the winners and the losers?

Racism

One-way social standards and class has been historically decided is through race and ethnicity. Marjoribanks and Farquharson (2011) defines race as a social construction based on appearance, skin colour, hair texture and facial features that many believe hold importance regarding the individual. Race and ethnicity continue to act as markers for national culture which determines whether individuals and groups that are deemed to fall outside this are targets for exclusion (Cleland, 2015).

Lusted (2009) states Football continues to play a leading role in discussions around the politics of ‘race’ and social integration in European nation-states. There are dominant claims that football is colour blind and racism is used to sustain white hegemony in the structures and subcultures of the professional game (Burdsey, 2007). Similarly, Bradbury (2013) suggests football remains a site in which the complex configuration of overt, culturally coded and more institutional forms of racism and discrimination are presented and generated in and through its practice and encounters. This is not just treatment towards the players, there are low levels of minority coaches in the amateur and professional game and Less than 1% of senior administrators at professional clubs and executive committee members at national and regional federations are from minorities (Bradbury et al. 2011). Despite all of this, Burdsey (2006) argues that racism is often denied within the football industry due to the increased participation and growing acceptance of African-Caribbeans in the game. Wagg (2004) suggests there are contemporary concerns with social exclusion in relation to a consumption driven football industry and its associated supporter cultures.

Global football governance

Cleland (2015) believes that colour blind ideologies exists amongst the games governing bodies. Similarly, Giulianotti and Robertson (2004) have the view that footballs national governance harbours significant problems associated with political representation and social exclusion and believe a reformed football governance could help to promote social inclusion within the game. Bradbury et al. (2011) suggest patronage and sponsored mobility are evident within the hierarchical pyramid structures of football federations tasked with governance of football at international level. Bradbury et al. (2011) For some authors, the concept, practices and outcomes of institutional racism in football are underpinned by the ‘invisible centrality of whiteness’ found within the senior organizational tiers of the game. Bradbury (2013) argues that it is the unremarked, everyday taken for grantedness of whiteness which has enabled the games key power brokers to maintain their powerful position as ‘inside’ and ‘included’, whilst minorities remain ‘outside’ and ‘excluded’ from key decision-making positions within powerful administrative and legislative bodies within the sport. This colour-blind ideology presented by the football governing bodies is absorbed by football fans and mirrored in their behaviours.

Supporter cultures

Football supporter cultures provide vivid and varied representations of social transnationalism and connectivity (Giulianotti and Robertson 2004). Furthermore, football culture affects individuals’ notions of self-identity, belonging and interpersonal relations (Stone 2007). Different national supporter groups converge, displaying their own identity including their own songs, dresses and behaviour (Giulianotti and Robertson 2004). Due to globalisation many spectator cultures at leading clubs undergo continuing revitalization which attracts more fluid followers to form diversity (Giulianotti and Robertson 2004). However, some supporter cultures refuse to adapt and alter their identity, therefore excluding people from their club.

Racial abuse has been an occurring problem in football to date. Bradbury (2011) states the historical legacy of spectator racism at professional football games has contributed significantly to the relative paucity of BME fans attending live games and has impacted negatively on the experiences of BME stadium communities. Moreover, Giulianotti and Robertson (2004) suggests poorly articulated supporter alienation can degenerate into extremist politics, as witnessed by rising racist and neo‐fascist spectator subcultures in parts of the continent. In Europe wider political narratives around national identity and citizenship and the practical implementation of policies of multiculturalism, integration, assimilation or non-intervention impact strongly on the everyday lived experiences of minority populations in different ways across different nation states (Bradbury 2013).

Arnold and Veth (2018) expresses the major concerns about Russian fans before the 2018 world cup in Russia, due to their extreme right-wing beliefs and racism. Russian supporters do not want black players playing in their county as it doesn’t fit their culture and identity. This was seen when Zenit st Petersburg fans created a club manifesto that states no purchase of a black player was allowed at the club. The manifesto was ignored by the club and not dealt with, which links back to the colour-blind ideologies held at powerful positions in the game.

Case study

Racial social exclusion has unfortunately been presented throughout football on a number of occasions. The international game takes players across the globe, with players representing their country in a proud moment for them and their family. In October 2019, England's 6-0 win against Bulgaria in Sofia was stopped twice and could have been abandoned as England players received racial abuse from the parts of the home supporters. The Bulgarian fans' behaviour included Nazi salutes and monkey chants and the match was stopped twice for racist chanting by home supporters. After the game, both the president of the Bulgaria Football Union (BFU), Borislav Mihaylov, and Bulgaria manager Krasimir Balakov resigned. Following from the events, the Bulgaria Football Union said in a statement "We sincerely believe that in the future, Bulgarian football fans will prove with their behaviour that they have unjustifiably become the subject of accusations of lack of tolerance and respect for their opponents,". This provides evidence for Cleland(2015) claim that ‘colour blind ideologies exists amongst the games governing bodies’ as the Bulgarian FU believe their fans have done nothing wrong and have ‘unjustifiably become the subject of accusations of lack of tolerance and respect for their opponents’. This further expresses the need for a global reform of football governance to help to promote social inclusion within the game (Giulianotti and Robertson (2004). The racial abuse projected by the fans was beliefs that were mirrored by the country and their governing bodies. This abuse left the black English players feeling socially excluded from other players in their own national team. In a sport where they should feel equal, the globalization of sport and expanding international tournaments has left them with a feeling of not being accepted.

Conclusion

The globalization process in football can present forms of racial social exclusion. This is presented through rigid supporter cultures that fail to accept anyone who doesn’t fit the clubs culture or identity. This is seen in international or European competitions where globalisation creates ethnoscapes and ideoscape global flows which mixes different individuals with different beliefs and backgrounds. This results in exclusion for that individual and also can create forms of racial abuse or miss treatment. The colour-blind ideologies that are held by national governing bodies transmit through a country or club and are presented by fans and supporters. This is seen in the case study where black England players were racially abused by Bulgarian supporters and the Bulgarian FU and manager believed they had not done anything wrong. Football governing bodies need a reform if football is to become a ‘sport that is increasingly recognized as a means for promoting social inclusion’ (Liu, p.1 2009).

References

Appadurai, Arjun. Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 1996.

Arnold, R., & Veth, K. M. (2018). Racism and Russian Football Supporters’ Culture: A Case for Concern?. Problems of Post-Communism, 65(2), 88-100.

Bradbury, S. (2011). From racial exclusions to new inclusions: Black and minority ethnic participation in football clubs in the East Midlands of England. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 46(1), 23-44.

Bradbury, S., Amara, M., Garcia, B. and Bairner, A. 2011. Representation and Structural Discrimination in Football in Europe: The Case of Minorities and Women, Loughborough: Loughborough University.

Bradbury, S. (2013). Institutional racism, whiteness and the under-representation of minorities in leadership positions in football in Europe. Soccer & Society, 14(3), 296-314.

Burdsey, D. (2007). Role with the punches: The construction and representation of Amir Khan as a role model for multiethnic Britain. The Sociological Review, 55(3), 611-631.

Burdsey, D. (2006). British Asians and football: Culture, identity, exclusion. Routledge.

Close, P., & Askew, D. (2004). 15 Globalisation and football in East Asia. Football Goes East: Business, Culture and the People's Game in East Asia, 243.

Cleland, J. (2015). A sociology of football in a global context. Routledge.

Giulianotti, R., & Robertson, R. (2004). The globalization of football: a study in the glocalization of the ‘serious life’. The British journal of sociology, 55(4), 545-568

Goldthorpe, J. H. (2002). Globalisation and social class. West European Politics, 25(3), 1-28.

Hargreaves, J. (2002). Globalisation theory, global sport, and nations and nationalism. Power games: A critical sociology of sport, 25-43.

Houlihan, B. (2003). Sport and globalisation. Sport & Society. A Student Introduction, London: Sage, 345-364.

Levitas, R. (2000). What is social exclusion. Breadline Europe: The measurement of poverty, 357-383.

Liu, Y. D. (2009). Sport and social inclusion: Evidence from the performance of public leisure facilities. Social Indicators Research, 90(2), 325-337.

Lusted, J. (2009). Playing games with ‘race’: understanding resistance to ‘race’equality initiatives in English local football governance. Soccer & Society, 10(6), 722-739.

Maguire, J. (2000). Sport and globalization. Handbook of sports studies, 356-369.

Marivoet, S. (2014). Challenge of sport towards social inclusion and awareness-raising against any discrimination. Physical Culture and Sport. Studies and Research, 63(1), 3-11.

Marjoribanks, T., & Farquharson, K. (2011). Sport and society in the global age. M

Miller, T., Lawrence, G. A., McKay, J., & Rowe, D. (2001). Globalization and sport: Playing the world. Sage.

Robertson, R. (1992). Globalization: Social theory and global culture (Vol. 16). Sage.

Spaaij, R., Magee, J., & Jeanes, R. (2014). Sport and social exclusion in global society. Routledge.

Stone, C. (2007). The role of football in everyday life. Soccer & society, 8(2-3), 169-184.

Tacon, R. (2007). Football and social inclusion: Evaluating social policy. Managing leisure, 12(1), 1-23.

Thibault, L. (2009). Globalization of sport: An inconvenient truth1. Journal of sport management, 23(1), 1-20.

Wagg, S. (2004). British football & social exclusion. Routledge.

Washington, R. E. (2010). Globalization and football.

1 note

·

View note

Text

A black principal, four white teens and the ‘senior prank’ that became a hate crime

By Jessica Contrera July 9, 2019

The principal saw a swastika first. It was inky black, spray painted on a trash can just beside the entrance to the high school. David Burton switched off the engine of his SUV, unaware, even then, of the magnitude of what he was about to see.

This was the last day of the year for the class of 2018 at Glenelg High School. There was going to be an awards ceremony, a picnic, that end-of-a-journey feeling that always made Burton so proud of his job. But as he was on his way to work at 6:25 a.m., the assistant principal had called, agitated and yelling about graffiti. “It’s everywhere,” he kept saying, so Burton had leaned on the gas and rushed the last few miles.

Soon, everyone would be telling him how shocked they were. This was Howard County, after all: a Maryland suburb between Washington and Baltimore that is extremely diverse, extremely well-educated and home to Columbia, a planned community founded on the principles of integration and inclusion. People moved their families here for that reputation just as much as for the good schools.

“Pleasantville,” Burton liked to call it, but as a black man, and as the principal of the county’s only majority-white school, he knew this place was more complicated. When he stepped out into the bright spring day, he confronted the reality of just how much more.

Beneath his dress shoes, there were more swastikas. Spray painted around them were crude drawings of penises.

Then Burton saw the letters “KKK.” He saw the word “Fuck” again and again next to the words “Jews,” “Fags,” “Nigs” and “Burton.”

He kept walking, following the graffiti around the building’s perimeter. It was on the sidewalks, the trash cans, the loading dock, the stadium around back. There were more than 100 markings in total, though he didn’t bother to count.

He turned a corner and saw something written in large capital letters on the sidewalk: “BURTON IS A NIGGER.”

He paused only for a moment, looking at the words, trying to comprehend that all of this was real.

Later, school district officials, county administrators and prosecutors would have a name for what happened here. They would repeat it, condemn it and vow to prevent it from occurring again. Hate crime.

The phrase has become inescapable as hate-fueled incidents have spiked across the country. A quarter of all hate crimes reported to the FBI, more than any other category, are similar to the attack discovered at Glenelg on May 24, 2018. Vandalism and destruction of property, a physical marking of an age-old threat: You don’t belong here.

The majority are repaired, washed away or painted over without anyone arrested. When the perpetrators are caught, they are rarely charged with a hate crime. Here, there would be consequences, and with them, a division between those who wanted to confront the racism in their midst and those determined to explain it away.

But first, Burton, 50 years old and dressed in one of his best black suits, would walk back over the graffiti, retreat into his office, close the door and pray.

His staff scrambled to cover the spray paint with tarps, carpet pads, anything they could find. The maintenance team searched for a sandblaster. But there was too much to cover and too little time before the students and parents began arriving. The seniors were wearing red caps and gowns, ready for their awards ceremony. Everyone was directed to alternative entrances, away from the worst of the damage. But photos of the graffiti were already being texted, emailed and Snapchatted.

In the auditorium, Imani Nokuri looked for her family, who had come to see her perform the national anthem. She was one of fewer than 20 black students in the class of more than 260 seniors. She and her younger sister, a freshman at Glenelg, had been rapid-fire texting all morning, comforting each other. But when Imani saw the look of deep concern her grandmother gave her, she forced a smile onto her face. “It’s okay,” she promised. “I’m fine.”

In the central office, teachers who had led diversity and empathy training for students were crying. Police were arriving, asking to see security footage. Phones were ringing with calls from reporters. Photos of the damage were about to be broadcast on TV, making their way into homes across the region.

In one of those homes, 72-year-old Susan Sands-Joseph was watching. She knew Glenelg well. She was one of the first black students to attend the school after desegregation. Suddenly, all the memories that she tried not to dwell on were dredged up again: the words she was called, the tomatoes thrown at her head, the looks her parents gave her when she came home saying scalding hot soup had been pushed into her lap again. “It’s okay,” she had promised them. “I’m fine.”

By the time the awards ceremony was about to begin, Principal Burton had rewritten the speech he had been planning to give. “We are not going to let this ruin your celebration,” he would now tell students.

He emerged from his office with notes clutched in his hand and stopped to check in with the police. The security footage, they told Burton, confirmed what he had suspected.

The principal entered the auditorium to a burst of applause. He stepped up to the podium. He stood before his students, looked out into their faces and felt certain: The people who did this were looking back at him.

Seth Taylor tipped his head down so his graduation cap would block his view of the podium. It felt, he said later, like the principal was staring right at him. But he and the others hadhidden their faces behind masks the night before, Seth reminded himself. How could anyone know they were the ones who had done it?All morning, he had been replaying the vandalism in his mind. He’d been at his buddy Matt Lipp’s house, where the parents of all their friends had gathered the evening of May 23 to sort out the details of Senior Week. The teens’ parents had rented them a house in Ocean City, the annual destination for thousands of local students celebrating graduation, and were divvying up tasks: who would drive the group to the beach, who would stock their fridge, who would cook them dinners before leaving them for a week of beer pong, sunburns and meetups with houses full of girls.Afterward, Seth stayed to watch a Washington Capitals playoff game. He loved these kinds of nights and, really, everything about high school. Cheering crowds at his football and baseball games, late-night Xbox sessions, fishing trips, parties in their parents’ basements. He could do without the academic part — he was a B student, at best — but he was planning to join the Army Reserve and maybe go to community college.With him at Matt’s was Josh Shaffer, a hockey player he’d been friends with since seventh grade, and Tyler Curtiss, the baseball team captain who had been homecoming king and prom king.Matt and Josh declined interview requests, but Seth and Tyler agreed to talk to The Washington Post about the vandalism. When they tell the story of that evening, they start with the end of the Caps game, when everyone but Seth was deep into a supply of Bud Light, and the conversation turned, once again, to their senior prank.

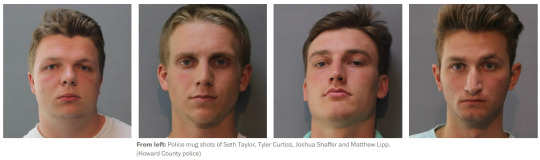

Seth Taylor

Tyler Curtiss

Tyler wanted to superglue locks. Seth suggested they grease up three pigs and release them into the school.

Or, somebody said, they could go spray paint the words “Class of 2018.”

Within minutes, they were driving to the school with spray paint from Matt’s parents’ garage. They parked at the church next door, tied T-shirts into masks over their faces and sprinted through the woods.

A shake of the can, the smell of fumes. The words went down easily, just as they had planned: “Class of 2018,” they wrote across the sidewalk.

And then Seth watched as Josh wrote something else: “BURTON IS A” it began.

Later, this was the moment he agonized over — the point at which he could have turned back. “I wish I said something, like, ‘This is stupid, guys. It’s not worth it. We could actually get in trouble for this.’”

Why he didn’t, he would always struggle to explain: “I don’t know. Everyone was doing it. We didn’t realize the consequences.”

“It was just spray paint. It just happened. It is all a blur.”

The blur went on for about seven minutes, during which all of them sprayed something hateful. Josh targeted the principal. Matt attacked Jewish, gay and black people. Tyler drew two swastikas. Seth drew swastikas, “fags” and “KKK.”

When a car drove by, they leaped behind the brick columns near the front entrance, hiding. A moment later, they started spraying again.

Finally, they ran back to their cars. They chucked their paint cans in the woods. They swore to each other that they would never admit what they did.

Seth came home to a quiet house. His sister was away at college, his father was on a business trip, and his mother was asleep. He went to the fridge and found the breakfast she had made for him to eat the next morning. Seth popped the eggs into the microwave. When he went to grab them, the plate slipped. The hot eggs tumbled onto his arms and legs. The shock somehow made it hit him. What had he just done?

Panicked, he started Googling:

“How long do you go to jail for vandalism?”

And then: “Can you get a hate crime for painting swastikas?”

Now he was sitting in the Glenelg auditorium, thinking about what he’d told his mom. Early that morning, she’d received an email from the school informing parents about the graffiti. Horrified, she texted Seth, warning him what he would find when he arrived at the awards ceremony.

“Who would do that?” he had texted back.

And in a sense, he meant it. He had already begun to separate what he’d done from who he believed himself to be. He hadn’t intended to hurt anyone, he said. He would always maintain he wasn’t an anti-Semite, a homophobe or a racist.

From the podium a voice said: “Tyler Curtiss.”

Seth looked up. His friend was walking toward the stage. But Tyler wasn’t getting in trouble. He was accepting an athletic leadership award. He was walking across the stage and shaking the principal’s hand.

Seth felt a tap on his shoulder. The athletic director was standing over him. “Seth,” he said quietly. “You need to come with me.”

Seth followed him out, trying not to look at his classmates. On the other side of the auditorium doors, two police officers were waiting to take him to the office of the school resource officer, Steve Willingham.

On the TV screen inside was security footage from the night before. Seth could see his own stout frame, paint can in hand, frozen in high definition.

“I bet you don’t want to see that, do you?” he remembers Willingham saying.

“No,” Seth answered.

“Do you know why you’re in here?”

“Yes,” Seth said. He didn’t know then that the officers had been strategic in pulling him out first. Willingham had coached Seth’s sister in soccer. He was friends with Seth’s dad. He suspected that of all the boys, Seth was the most likely to confess.

It took only one question: “What happened?”

“Things got out of hand,” Seth recalls telling him. “I was under the impression we were going to do a prank, and it got bad.”

He started to cry. He would be the only one who immediately admitted what they did. The others, court records show, would deny it. Tyler wished Willingham good luck in finding out who did it.

Eventually they were told: The school’s WiFi system requires students to use individual IDs to get online. After they log in once, their phones automatically connect whenever they are on campus.

At 11:35 p.m. on May 23, the students’ IDs began auto-connecting to the WiFi. It took only a few clicks to find out exactly who was beneath those T-shirt masks.

“You have the right to remain silent,” an officer said to Seth before long. “Anything you say or do . . . ”

They told him to remove his graduation cap and gown. They cuffed his arms behind his back.

Seth realized they were about to march him outside, past the windows of the cafeteria. By now it would be filled with students eating lunch.

“Can you cover my face so that the kids don’t videotape me?” he asked.

“No,” an officer replied. “You deserve this.”

By the end of the day, charges had been filed. Not just vandalism and destruction of property, but a hate crime. Prosecutors believed the young men had committed their acts with animosity toward protected groups — and that they could prove it. In Maryland, that meant that the punishment could be intensified. It meant they were looking at up to six years of incarceration.

Before they were released from jail that night, the four students watched on a small TV screen outside their holding cell while their crime was broadcast on the local news — as it would be over and over in the coming days. Viewers saw four white teens, scowling at the camera, and the school system’s superintendent vowing at a news conference to hold them accountable.

“Howard County stands out as a place where diversity and acceptance are cherished,” Michael Martirano said. It sounded like something any superintendent would say. But here, many knew, it came with a story: one taught to children in school, bragged about to visitors and proclaimed on signs.

In the early 1960s, before the Fair Housing Act and the legalization of interracial marriage in Maryland, a white developer named James Rouse began purchasing huge swaths of Howard County farmland to build a planned community named Columbia.

He envisioned it as a mixed-race, mixed-income utopia. “The next America,” he called it, and although racial tensions could never be completely erased, to many people, that is what it became. Today, the suburb — home to a third of the county’s 300,000 residents — is renowned for its ethnic diversity, interracial marriages, interfaith centers and high-achieving schools. It appears frequently on national “Best Places to Live” lists.

Most are unaware of the history that came before Columbia. The farmland Rouse purchased included former slave-holding plantations. An estimated 2,800 people were enslaved in the county at the beginning of the Civil War. A century later, when the Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 that schools must be desegregated, Howard County was so resistant that it took more than a decade for the black-only school, Harriet Tubman, to close its doors. The opposition to black students learning alongside white ones was so fierce, a cross was burned. It happened outside a school dance at Glenelg High School.

Glenelg is in western Howard, the most rural part of the county, then and now. While the rest of Howard’s high schools have no racial majority, 76 percent of Glenelg students are white.

On the news that night, though, only students of color were interviewed.

“It’s just a small number of students who decide to make these decisions that negatively impact the image of our school,” one said.

“This is not representative of what Glenelg stands for,” said another.

That week, after Seth, Tyler, Matt and Josh were released from jail without having to pay bail, their classmates began to argue over whether those statements were true.

Tyler Hebron, a senior who was president of the school’s black student union, typed her feelings into an Instagram post. “It shouldn’t have taken this event to occur for us to observe the hateful actions of our peers,” she remembers writing. “We shouldn’t say we are surprised. We are not.”

During her freshman year, a student flew a Confederate flag at a football game. Swastikas were scratched into the bathroom stalls. In 2017, someone had written the n-word and Principal Burton’s name on a baseball dugout. She had heard boys play a game to see who could yell the n-word the loudest. To her, this crime was just high-profile proof of the hostility she had always felt.

Soon, comments started appearing beneath her Instagram post.

“You’re racist,” one said. “All you do is blame straight white males.”

The night before graduation, she found herself thinking about whether she should pack pepper spray in her purse. She wasn’t sure, she told her parents, that she felt safe.

Among black families like hers, there were doubts that the white teens would face the kind of punishment black teens receive for similar crimes. Two years earlier, a group of students had painted swastikas on a historic black schoolhouse in Northern Virginia. A Loudoun County judge sentenced them not to jail time or community service, but to reading: along with visiting the Holocaust museum, each had to choose a single book about Nazi Germany or the Jim Crow era and write a report on it.

Two black families came to Burton and told him they were pulling their kids out of Glenelg before the next school year. The principal tried to persuade them not to go.

But in his own house, his wife, Katrina, was wondering if he should leave, too.

They had two daughters to think about, an eighth-grader and a senior at another Howard County high school, who on the day of the hate crime had come home and collapsed in her mother’s arms, sobbing. Katrina knew about the parents who warned Burton not to talk about the incident in his speech at the graduation ceremony, and watched as some of them refused to stand and clap for him that day.

“Are you safe?” she kept asking her husband.

There had been so many incidents in his life that had made Burton question just that. When he was 16, and the parents of a white friend in his Michigan hometown called him the n-word. In college, when he and his fraternity brothers were pulled over and questioned by a group of white cops seemingly for no reason. At a convenience store in South Carolina just a few years ago, when a hostile clerk refused to serve him and his family.

But inside a school, he was an authority figure, the man in charge. For most of his career, he’d led schools in Prince George’s and Howard counties filled with students of color.

And then to his surprise, he was asked in 2016 to leave Howard County’s Long Reach High School, where a third of the students are black, and take over at Glenelg, where less than 5 percent are black. Here, he suspected, it would take time to win over the community.

He started standing in the halls every morning and every class break, looking students in the eye as he said hello. He attended as many games and plays and art shows as he could. He made sure the swastikas scratched in the bathroom were documented and investigated, but quietly, to avoid giving those who drew them the attention they were seeking.

After two years, he felt that he had earned the respect of this place, and these people. They welcomed him when he arrived at the annual end-of-the-year celebration for the senior class at an Ellicott City resort. Parents gave him hugs and thanked him for what he had done for their kids.

That night, he learned that one senior had been caught trying to order alcohol at the bar. The student was kicked out of the event, but the next day, Burton decided he didn’t want to be overly harsh in his punishment.

“Even though you did this, I am going to allow you to go to the school picnic,” he told the teen.

Less than a week later, it was the same student, Josh Shaffer, who would scrawl Burton’s name and the n-word onto the sidewalk.

“The person you married is not about to cower,” the principal told his wife. He wouldn’t be leaving Glenelg.

He could use the summer, he thought, to plan what he was going to do the following school year, the message he needed to send.

And if the prosecutors sought his help in holding his students accountable, he knew what his answer would be.

Every time Seth walked from the parking lot of the Howard County Circuit Court to its entrance, he passed a small, decaying building with barred windows and a slanted roof. He rushed by with his head down, passing a plaque that explained the structure's history. Here, slaves who'd tried to run to freedom were held before being returned to the people who owned them.

In late March, Seth entered the courthouse dressed in one of his father’s suits, accompanied by his parents. It was his final appearance in front of the judge overseeing all four Glenelg cases: William V. Tucker, a black man with a reputation for his interest in the way the criminal justice system handles young people.

One by one, they had come before him and pleaded guilty, or been found guilty after agreeing to a statement of facts.

Two of them had tried to have the hate-crime charges dismissed. Their attorneys claimed that their First Amendment rights were being violated. They could be punished for the vandalism, the argument went, but not for what they wrote.

It didn’t work.

Now, it was Tucker’s job to answer a question the community had been debating for nearly a year: What consequences did these young men, now 19, deserve?

They hadn’t been allowed to walk at graduation. Their post-high-school plans had been derailed, and they were working in landscaping, asbestos removal and, in Seth’s case, office furniture construction. Their names and mug shots were seared into Howard County’s memory and the Internet’s search results. It was up to Tucker to decide whether, on top of that, they should spend time in jail.

His view became clear when Joshua Shaffer was the first to be sentenced on March 8, 2019. Seth stayed home and kept refreshing his Internet browser, waiting for news. Finally, the local TV station published a video: Josh was being walked out of the courthouse in cuffs. He had been sentenced to three years of probation, 250 hours of community service and 18 consecutive weekends in Howard County Jail.

Seth’s parents called his attorney, Debra Saltz, in a panic. His case was different, she reminded them. He was different. They just had to persuade the judge to see that.

Saltz stood in court that March morning and pointed to her client.

“Your honor, I truly believe justice and mercy call on us to consider who he is,” she said. “And I believe it requires the court to consider what has happened in his life, what he has done since May 24.”

Seth, she explained, had been working to make amends. He’d completed 181 hours of community service. He’d written an apology letter to Principal Burton. He’d visited the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington and volunteered at the Jewish Museum of Maryland. He’d spent time with an African American pastor and attended regular diversity training with an African American counselor.

He did it all with the support of his parents, who had spent the year agonizing over how their son could have done something so heinous. Seth’s father, Scott Taylor, stood to tell the judge he blamed himself.

“The letters ‘KKK’ were painted on the school. Seth didn’t understand the pain, suffering and terror associated with those letters, because I never told him,” the father said. “I never told him how the Klan used to collect money after church in my neighborhood when I was growing up in the South, and how they would stand in the road like the fire department.”

“I’ve come to realize I did fail,” he continued. “It’s not what I said in my home; it’s what I didn’t say.”

When it was Seth’s turn to speak, he assured his parents that it was not their fault.

“You taught me better,” he said. “This isn’t who you raised.”

He apologized to the principal and to the communities he hurt.

“It was the worst decision I have ever made in my entire life. What I did there keeps me up at night. I deserve whatever punishment I get,” he said. “I have worked hard since that day to show my family, my school, my community and Principal Burton how sorry I am.”

Seth said he just wanted all of them to understand: He is not a racist.

Later, he would explain himself this way: “I never really understood the symbol of the swastika. I knew it was wrong to plaster it somewhere. I didn’t learn exactly what [the Nazis] were doing to the Jews until I went to the Holocaust Museum. I never learned that they were mutilated. I knew that they were, like, burned. But I never learned that they had experiments done on them, were injected with diseases. The school didn’t include that. They just included the burning and the train cars.”

His understanding of the KKK was limited, too, he said. “Some people think it’s just a word, or a symbol or three letters put together. . . . But they were lynching people, hurting people for no good reason.”

Now, he said, he knows. But he still doesn’t believe his actions that night make him a bigot.

“I spray paint one racist thing and, suddenly, I become a racist? Just because I did it doesn’t mean I hate Jews, gay people or black people.”

He was standing before the judge, pleading guilty to a hate crime, but he would not admit that he harbored any hate.

All around him, the adults agreed.

“He will forever be known as the racist kid at Glenelg, but that’s not who Seth is,” his father said in court that day.

“I told him that his act was racist, but don’t let it define him as a racist. He can and I pray that he will go on and do better,” Maxwell Ware, the African American pastor he met with, wrote in a letter supporting him.

“He is not a racist . . . he has a good heart,” his attorney told the judge.

Behind her, Principal Burton was listening. He’d heard Joshua Shaffer’s attorney give a similar speech. When Matthew Lipp was sentenced, he would hear it then too. Tyler Curtiss had written it in a Facebook apology the day after the crime. Tyler, Burton knew, had turned to Jesus, joining a church where he talked openly about the swastikas he painted that night. He had spent months telling his story to Jewish congregations, interfaith groups and the county’s board of rabbis. Come the day of his sentencing, Tyler would say: “I hold no hatred toward any human being, especially those in the communities that were affected.”

They all believed it was possible to do what they did without really meaning it.

Burton wanted to look them in the eye and say: “You did something very racist. How you don’t think you’re a racist, I don’t know.”

What he did know was what they’d been taught in school: Glenelg covered the Holocaust and the Klan in detail, in U.S. history and American government and world history and in the books they read for language arts.

He believed what possessed them to draw those words and symbols that night wasn’t a lack of knowledge, but something deeper, something ugly, something taught to them, consciously or unconsciously, along the way. If they couldn’t admit that now, maybe they never would. But it wasn’t his responsibility to educate them any more.

When it was Burton’s turn to speak at Seth’s sentencing, he didn’t say the word “racism.” He talked about all the people the crime had affected — the teachers crying in his office, the parents who pulled their kids out of his school, his daughter in tears, and for just a few moments, himself: “I know I give up my time, my effort, I give up my life for my students,” he said. “I think the only thing I am asking in return is just a little bit of respect.”

The courtroom waited in silence for Judge Tucker to reach his decision. Seth kept his gaze on the table. His father rubbed his mother’s back.

“I appreciate the fact that you are now trying to show that you are not a racist, that you committed a racist act,” Tucker finally told Seth. “But part of what I need to do is punish you. So the sentence is going to be as follows.”

Three years probation. Two hundred fifty hours in community service. And nine consecutive weekends in jail.

“A normal weekend incarceration is Friday 6 p.m. to Sunday 6 p.m.,” Tucker said. It was a Thursday. “For this weekend, it begins today.”

A black sheriff’s deputy stepped behind Seth and pulled out her handcuffs. His mother began to cry.

“Alright, Mr. Taylor, good luck to you,” the judge said, and the metal closed around Seth’s wrists.

Six weeks later, Seth backed his car out of his parents' driveway, headed to his final weekend in jail.

Good behavior during his weekends locked up meant he had to serve only two-thirds of them.

The following weekend, Tyler Curtiss, who had painted two swastikas, would finish his weekends, five in all.

Matt Lipp, whose graffiti attacked Jewish, black and gay people, would serve 11 of the 16 he was sentenced to. He has filed an appeal, still arguing that his First Amendment rights had been violated.

Josh Shaffer, who targeted the principal, was sentenced to the most jail time: 18 weekends. He would serve 12.

All four will be eligible to get the hate crimes expunged from their record when their probation is finished.

Together they had figured out how to navigate their 48-hour stints locked up: how to make the time pass, how to hide their toilet paper so it wouldn’t be stolen, what to do when the other inmates threw dominoes at their heads.

Seth didn’t know the names of the people who gave them trouble, but he had nicknames he made up for them. “String Bean,” for the tall, lanky one. “Pistachio” for the one with the mustache.“

Two black kids who just do not like us,” he called them.

Now he drove past the high school, yawning as he turned toward the highway. He’d been up late the night before, playing Mortal Kombat with strangers on his Xbox. He felt comfortable there, behind the anonymity of his username. He didn’t feel that way anywhere in Howard County. He grew nervous anytime he saw a person of color, wondering if they recognized him and knew what he had done.

He didn’t think anyone would recognize him come Monday, when he was going to start a new job in a heating and cooling apprenticeship program an hour away. It was going to pay $14 an hour. If he liked it, he might get his HVAC license. And then in three years when his probation was over, he thought he might move to Florida. Do some fishing. Start over.

He pulled into the jail parking lot 20 minutes early, switched off his engine and pulled out his phone. He turned on Kodak Black, who started rapping about “nigga s---.”

A truck pulled up beside him and Seth rolled down his passenger window.

“Hey,” he called to Josh. The two were the only ones in the group who had stayed close friends. During the week, they went to the gym together late at night, when they wouldn’t see other people.

“You ready to play three hours of checkers?” Josh asked.

“I’m finding a book, man,” Seth said. “I can’t play Uno again. I’m never playing Uno again in my life as soon as I leave this jail.”

Josh pulled out a can of tobacco dip. Seth took a hit from his strawberry-flavored Juul. They sat there until Josh said, “You ready?” and then Seth followed him inside.

The principal steered into the high school lot a month later and parked in the same spot he had a year before. He stepped out of his SUV in one of his best black suits. It was the last day of school for the class of 2019.

Once again, there was going to be an awards ceremony and a picnic, but this year, there was no graffiti waiting for him.

In the weeks since his former students were sent to jail, he and his wife had been asked again and again what they thought of the punishment. People were outraged — either that the young men had received a “slap on the wrist” or that they had been so persecuted. Burton wouldn’t take a side. “To me, it felt like a crime,” he said. “But what happens because of that crime is not up to me to figure out.”

He had to focus on his 1,200 current students: the LGBTQ kids who still felt isolated. The Jewish girl who told the local paper she still wishes she could transfer. Whoever was still scrawling swastikas on the bathroom stalls.

In the past year, he’d created a task force of diverse students to work on the school’s climate. Soon every freshman would go through an empathy workshop. And nearly 40 of his employees had spent the year meeting to discuss the book “Waking Up White,” a memoir of a white woman who comes to understand that racism is a system that she had been shaped by and contributed to her entire life without even realizing it. Maybe, he thought, that lesson would get passed on to Glenelg’s students.

But on this morning, his job was to celebrate his seniors. He stood outside as they arrived in their red caps and gowns. Their parents and grandparents followed behind, cameras in hand.

Then he saw it: this year’s version of a senior prank. A tractor was pulling into the parking lot. On the front was an old couch bolted to the forklift, a sign that read “2019,” and a few students sprawled on the cushions. On the back was a blue flag. “TRUMP,” it read, “MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN.”

The assistant principal set off after them, and Burton decided to let him handle it. Instead he made his way to the auditorium. He stepped up to the podium, looking out at his students’ faces. Then their names were called, and they came on stage to shake his hand.

#Seth Taylor#Matt Lipp#Josh Shaffer#Tyler Curtiss#Glenelg High School#racism#hate crime#Maryland#donald drumpf#donald tRump#drumpf#drumpfster fire#dumpster fire#make donald drumpf again#this is not normal#this isn't normal#tRump#tRump is not normal#tRump isn't normal#tRumpster fire#fuck this republican administration

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Bear’s Den, December 3, 2018

BEAR DOWN, CHICAGO BEARS, BEAR DOWN!!!!

BEARRRSSSS

Haugh: Bears’ Loss More Frustrating Than Devastating - 670 The Score - All the Bears’ goals remain attainable despite an overtime loss to the Giants.

Emma: Bears Remain Optimistic In Aftermath Of Letdown Loss - 670 The Score - ”I’m proud of them for fighting to the end,” coach Matt Nagy says.

Emma: Bears QB Mitchell Trubisky Close To Return From Shoulder Injury - 670 The Score - With Trubisky sidelined, Chase Daniel struggled in a loss to the Giants.

Emma: Bears’ Matt Nagy On Costly Timeout Before Halftime - ‘I Take Responsibility For That’ - 670 The Score - Matt Nagy’s decision allowed the Giants to hit a field goal that proved crucial later.

Bernstein: Bears Can’t Overcome Themselves On Crazy Day - 670 The Score - The Bears didn’t deserve to win on a day they fell in overtime to the Giants.

Bears Lose Wild Overtime Contest To Giants - 670 The Score - The Bears rallied from down 10 late to tie before falling 30-27.

Chicago Bears-New York Giants Postgame Show: Bears Fall Short in Overtime After Epic Last-Minute Comeback - Da Bears Brothers Podcast - Da Bears Brothers share their comprehensive game recap with their instant analysis and insight on the Chicago Bears Week 13 loss to the New York Giants.

Kane: Bears force overtime with wild comeback but see winning streak snapped in 30-27 loss to Giants - Chicago Tribune - Bears quarterback Chase Daniel helped send the game against the Giants to overtime Sunday afternoon at MetLife Stadium, but he couldn’t complete the comeback as the Bears lost 30-27.

Stankevitz: Bears leave absurd loss to Giants with prevailing feeling: ‘We’re better than that’ - NBC Sports Chicago - The Bears had a lot of self-inflicted mistakes in Sunday's overtime loss to the Giants. They believe they can and will do better going forward.

Stankevitz: Mitch Trubisky still day to day as Chase Daniel shoulders blame for Bears’ loss - NBC Sports Chicago - After the game, Matt Nagy continued to classify to Trubisky as day-to-day.

Stankevitz: Bears don’t quit, but it’s not enough in overtime loss to Giants - NBC Sports Chicago - The Bears' inspired comeback came up just a bit short.

Ellis: Only one other NFL player has ever had the type of game Tarik Cohen had today - NBC Sports Chicago - Only one other player has ever had a receiving performance like Cohen did today ... and he's a hall of famer.

Under Center Podcast: Bears come back but come up short - NBC Sports Chicago - Laurence Holmes, Lance Briggs and Alex Brown explain why the Bears-Giants game felt off from the very start.

Game Recap: Bears rally but fall in OT thriller - ChicagoBears.com - The Bears scored 10 points in the final 1:13 of regulation Sunday in New York, but ended up losing a 30-27 overtime thriller against the Giants.

Pace talks Bears on pregame show - ChicagoBears.com - Bears general manager Ryan Pace appeared on the WBBM Newsradio 780 AM and 105.9 FM pregame show in advance of Sunday’s contest against the Giants.

Ugggggggh: Giants 30, Bears 27 (OT) – December 2, 2018 - Bleacher Nation - The Chicago Bears lost a game they had no business losing. Or is it that they had no business winning it? Either way, ugggggggh!

Nagy on Bears' trick play: 'It wasn't a hard choice' - ESPN Video - Bears head coach Matt Nagy details Chicago's trick play and prides his team for its execution.

Potash: Not their best work - ’Sloppy ... undisciplined’ Bears defense pays the price - Chicago Sun-Times - After allowing 74 yards on 24 plays (3.0 avg.) prior to the Barkley run, the Bears allowed 266 yards on 44 plays (6.0 avg.) the rest of the way.

Morrissey: Bears drop thrilling, painful game to Giants - Sun Times - Do you applaud them for a valiant comeback behind a backup QB or do you take them to task for not winning a game they should have won? Answer: Both.

Finley: Coach Matt Nagy's aggressiveness helps, hurts Bears in 30-27 loss to Giants - Chicago Sun-Times - At the end of regulation Sunday, Bears coach Matt Nagy was at his aggressive best. At the end of the first half, he was at his aggressive worst.

Jahns: Giants 30, Bears 27 0 It's time for Mitch Trubisky to return for Bears - Sun Times - Bears quarterback Mitch Trubisky missed his second game in a row because of his shoulder injury.

Finley: Bears upended by Giants in topsy-turvy overtime game - Chicago Sun-Times - The Giants were content to run to the locker room, it seemed. Then Bears coach Matt Nagy took a timeout that would prove a turning point.

Finley: The Fridge, Part II? Bears DL Akiem Hicks scores on handoff - Sun Times - Chase Daniel handed the ball off to Akiem Hicks, who plunged for a score.

Campbell: 'I let my team down.' Chase Daniel's 2 interceptions, 5 sacks and 4 fumbles dig Bears a hole they can't escape - Chicago Tribune - Bears quarterback Chase Daniel threw two interceptions, fumbled four times and was sacked five in the 30-27 overtime loss to the Giants on Sunday.

Wiederer: Gritty comeback? Horrible loss? Wacky overtime game with Giants leaves Bears dizzy - Chicago Tribune - In a wild affair in New Jersey, the Chicago Bears lost 30-27 in overtime to the New York Giants, squandering a gritty late comeback with too much overall sloppiness. Now at 8-4, the first-place Bears needs to move on quickly.

Kane: Surprising call at the end of regulation results in Tarik Cohen-to-Anthony Miller tying TD pass - Chicago Tribune - The Bears had been practicing the play called "Oompa Loompa" for months. So when they had the ball on the Giants 1-yard line with three seconds to play in regulation, Bears coach Matt Nagy made the surprising call.

Rosenbloom: Bears gag a chance to move closer to a playoff bye - Chicago Tribune - This was a bad loss. The Bears's 30-27 OT loss to the Giants showed they hadn’t learned from an OT road loss to the Dolphins earlier in the season. All the Bears needed Sunday in the Meadowlands was to get out with a win and get healthy. At least they’re healthy. Hopefully they’ll get smarter.

Alper: Chase Daniel - I let my team down – ProFootballTalk - Bears quarterback Chase Daniel was able to guide the team to a win on Thanksgiving in his first start since the 2014 season, but things didn't go nearly as well against the Giants on Sunday.

Finley: Bears coach Matt Nagy mum about Kareem Hunt - and Bears' plans - Chicago Sun-Times - The star Chiefs running back who was cut Friday after video surfaced of him assaulting a woman.

Finley: Via the pass, catch and run, Bears' Tarik Cohen being 'the playmaker I am' - Chicago Sun-Times - He set a career high with 186 scrimmage yards. His career-best 156 receiving yards were the most by any Bears running back since at least 1960.

POLISH SAUSAGE

Kareem Hunt: Kansas City Chiefs were right to cut me - NFL.com - Kareem Hunt took responsibility for the actions that led to his release by the Chiefs on Friday, saying the team was right to cut him after video showed him pushing and kicking a woman.

KNOW THY ENEMY

Vikings fail to pick up game on Bears in NFC North, but still control playoff fate - ESPN - The Vikings (6-5-1) are still alive in the NFC playoff picture, but they still haven’t beaten an opponent with a winning record.

5 coaching decisions that may have cost the Lions the game vs. Rams - Pride Of Detroit - Coaching played a huge part in Sunday’s loss to the Rams.

3 things we learned in the Detroit Lions’ loss to the Los Angeles Rams - Pride Of Detroit - Detroit came close, but ultimately fell short against one of the best teams in football.

New England Patriots 24, Minnesota Vikings 10: Vikings come up small in big game - Daily Norseman - They had their opportunities, but couldn’t take advantage

Packers’ 2018 season is over after unthinkable 20-17 loss to hapless Cardinals - Acme Packing Company - Mason Crosby’s kick sailed wide right in a game Green Bay never looked like it deserved to win.

Odell Beckham: Don’t question my effort – ProFootballTalk - The Giants became one of the few teams to fall victim to an onside kick after the league’s rules for kickoffs changed this offseason and that gave the Bears life at the end of regulation on Sunday.

Packers fire coach Mike McCarthy after 13 seasons - NFL.com - The Mike McCarthy era in Green Bay is over. The Packers announced Sunday that they have fired the head coach of 13 seasons. OC Joe Philbin has been named interim coach.

Detroit's Take: Green Bay Packers fire Mike McCarthy after 13 seasons - Pride Of DetroitThe - second head coach firing of the season has happened. And it’s coming from inside the division.

Green Bay's Take: Mike McCarthy fired as head coach of the Green Bay Packers - Acme Packing Company - It finally happened.

IN CASE YOU MISSED IT ON WINDY CITY GRIDIRON

Wiltfong: Packers fire head coach Mike McCarthy - Windy City Gridiron In a move that - shouldn’t come as much of a surprise, the Green Bay Packers have fired head coach Mike McCarthy just hours after they lost to the Arizona Cardinals 20 to 17, to fall to 4-7-1 on the...

Curl's 2018 NFL Week 13 Postgame: Bears take it to overtime but unable to recover from big mistakes in 30-27 loss to the Giants - Windy City Gridiron - After a 5 game win streak, the Bears tease us with some magic at the end but walk away from Met Life stadium with a loss.

WCG CONTRIBUTORS BEARS PODCASTS & STREAMS

2 Minute Drill - Website - iTunes - Andrew Link; Steven’s Streaming – Twitch – Steven Schweickert; T-Formation Conversation - Website - iTunes - Lester Wiltfong, Jr.; WCG Radio - Website - iTunes - Robert Zeglinski

THE RULES

Windy City Gridiron Community Guidelines - SBNation.com - We strive to make our communities open and inclusive to sports fans of all backgrounds. The following is not permitted in comments, FanPosts, usernames or anywhere else in an SB Nation community: Comments, FanPosts or usernames that are intolerant or prejudiced; racial or other offensive epithets; Personal attacks or threats on community members; Gendered insults of any kind; Trolling; Click link for full information.

The Bear’s Den Specific Guidelines – The Bear’s Den is a place for Chicago Bears fans to discuss Chicago Bears football, related NFL stories, and general football talk. It is NOT a place to discuss religion or politics or post political pictures or memes, and any posts that do this will be deleted and the poster will be admonished. We do not allow comments posted where the apparent attempt is to cause confrontation in the community. We do not allow gender-directed humor or sexual assault jokes. The staff of WCG are the sole arbiters of what constitutes “apparent attempt to cause confrontation”. We do not allow the “calling out” of other members in any way, shape or form. Posts that do this will be deleted on sight. Bottom line, it’s fine to debate about football, but personal jabs and insults are strictly prohibited. Additionally, if you keep beating the same dead horse over and over and fail to heed a moderator’s warning to stop, you will be banned.

Click on our names to follow us on Twitter:

WCG Contributors: Jeff Berckes; Patti Curl; Eric Christopher Duerrwaechter; Kev H; Sam Householder; Jacob Infante; Aaron Lemming; Andrew Link; Ken Mitchell; Steven Schweickert; Jack Silverstein; EJ Snyder; Lester Wiltfong, Jr.; Whiskey Ranger; Robert Zeglinski; Like us on Facebook.

Source: https://www.windycitygridiron.com/2018/12/3/18122957/chicago-bears-2018-season-news-updates-analysis-game-twelve-new-york-giants-daniel-mccarthy-nagy

0 notes

Text

For centuries, the transgender people have been ubiquitous in the population of our country – from the times of royalties to the busy, bottleneck traffic of Indian streets, they are everywhere. One might argue that they are not much visible in the professional settings, but is that really true?

There are hundreds of people around us, working with us, taking the same bus, train or metro with us who do not conform to the gender they were assigned at birth. But the fact that they do not cannot express that outwardly with their behaviour or appearance is where the real issue lies.

The psyche of the Indian people is conditioned to stereotype transgenders as people who sing at weddings, bless a newborn, beg at traffic jams or on trains and are involved with sex work. Automatically in their mind, they associate the community with substandard occupations; but what they do not want to think is the reason why they are forced to take up these jobs.

source: https://goo.gl/1JFRFJ

If identifying as genderqueer is a challenge in India, coming out as a transgender is even more difficult. From subtle alienations to getting ousted from family to full-blown hatred, the hurdles come in a wholesome package deal.

However, with the Government and the legislation taking baby steps towards enforcing equal rights for the community, a handful of organisations and society members are coming forward to work towards debunking the taboos and myths and including them in the mainstream.

Kerala is the torchbearer of this crusade among the Indian States.

In September 2015, Kerala became the first State to bring out a policy to give the marginalised transgender community what they truly deserve. The social justice department’s draft was in compliance with the Supreme Court’s 2014 judgement recognising the community as the third gender.

source: https://goo.gl/sQB6he