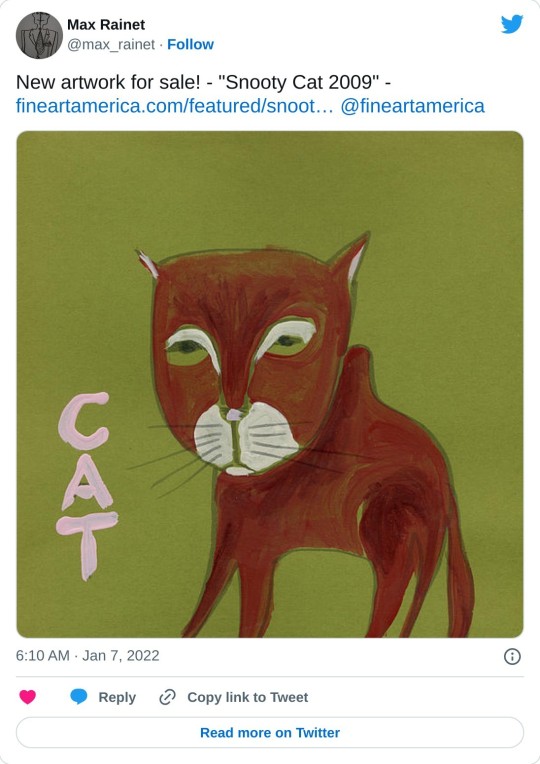

#Snooty Cat 2009

Text

#Snooty Cat 2009#Books#Art#Collectibles#For Sale#Max_Rainet at Ebay#bookshop#art dealer#retail guru#RT @max_rainet: New artwork for sale! - - https://t.co/1q7D5fYsic @fineartamerica https://t.co/6W94zKMBpX

0 notes

Photo

Happy Birthday our longest running comic, first published on July 30th 1938 the Beano is 80 years old today! .

An ostrich called Big Eggo was the front page star, and the comic only cost 2d. The central composition was also different. While the modern Beano is entirely based on comic strips, the early Beano had stories told with pictures with text beneath explaining what was going on, and stories told only with text. It also lacked many of the characters that are synonymous with it now, Dennis, Rodger and Minnie only arriving in the golden years of the 1950s.

A few months before The Beano came its sister paper, The Dandy, and a year after another sister, The Magic comic. Due to the Second World War however, only two of these were to survive. The war meant that comics had to use fewer pages, by printed in lesser numbers and less often. This meant that the Beano and Dandy were made smaller, only available to those who pre-ordered them, and were only printed on alternate weeks. They provided a vital service in the war, warning children to leave alone things like mines on beaches and printing stories to outline the difference between Nazis and normal Germans and so teaching children not to demonize people based on nationality. They also pictured the enemy leaders as bungling fools, such as in The Beano strip, Musso the Wop and in the many times that Lord Snooty and pals went to give the Fuhrer a piece of their mind.

The 1950s is thought to be the golden age of The Beano as so many of the most popular and long running characters were created then, such as Dennis the Menace, Minnie the Minx, Rodger the Dodger and the characters that would eventually become known as The Bash Street Kids, whose original incarnation was a basically identical story called When The Bell Rings.

As well as it's regular characters, the Beano also had it's supply of irregulars, who popped in every so often for one off-stories. These were usually less cartoony, the characters looking more realistic and detailed, and the stories themselves were often more serious. These stories included General Jumbo and The Iron Fish. A more recent example would be Billy The Cat.

In September 2009, The Beano's 3,500th issue was published it will strike 4000 in the summer of 2019.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Any animal is more elegant than this book: The Elegance of the Hedgehog

Unfortunately, this has to be the top contender for the worst “good” book I’ve read to date. So many words, so little substance– I’m shocked at how many words can be written about nothing much.

I really wanted to like this book, guys, I really did. I liked Heidi Sopinka’s “The Dictionary of Animal Languages”, which has the same stylistic fragrance that Hedgehog attempts.

The difference?

The narrator of Languages brightened my world, while I was suffocated by the alternating narrators here, named Renee and Paloma.

Renee is a concierge approaching her sixties while Paloma is a twelve-year-old intellectual prodigy who loves writing in her journal and wrist-wringing over the constant trauma of living in, uh, a patently elite apartment complex in a gorgeous Paris neighbourhood where she is surrounded by relatively pleasant people and their pampered pets. Renee, who unflinchingly pronounces herself as stout and ugly, works in this apartment complex, and takes extreme precautions to ensure that the residents never find out that she is passionate about fine art, loves experimental cinema, and worships the literary canon. She also has a cat named Leo, after Leo Tolstoy, and is at all times paralysingly worried that the residents will get the reference.

First of all, the central premise is questionable and absurd in that it goes great lengths to cloyingly counterpreach the stigmatisation of something that may not even be a stigma. The book in 140 characters or less: a concierge affectedly and pompously demonstrates that it is okay for her to be intelligent. Here’s an excerpt:

“Concierges do not read The German Ideology; hence, they would certainly be incapable of quoting the eleventh thesis on Feuerbach. Moreover, a concierge who reads Marx must be contemplating subversion, must have sold her soul to the devil, the trade union. That she might simply be reading Marx to elevate her mind is so incongruous a conceit that no member of the bourgeoisie could ever entertain it.”

The problem with this is that I don’t think anyone in the apartment complex would care if they found out that Renee was intelligent. Renee takes up half her narrative time belabouring how difficult it is to be someone who betrays societal expectations by being a smart concierge. Not once is her delusional hypothesis put to the test. Not once was Renee allowed to wonder whether, in fact, people had something against smart concierges at all. If she were, this brittle plotline would disappear and invalidate the whole book.

Second, there are many characters living in the apartment complex, and I was interested in getting to know them. Colombe, Paloma’s older sister, was especially interesting! I did my best to piece together a portrait of her through Paloma’s exasperatingly condescending and hate-filled journal entries. I couldn’t help but feel that the fake-deep so-called “social commentary” was self-defeating and managed to destroy the storytelling.

Where’s the due social commentary about hypocrites? You won’t find it in this book narrated by snobs devoid of self-reflexivity.

What’s worse is that the musings of Renee and Paloma are less sincere social commentary than snooty flexings of how brutally they can tear down other people. The other characters are ruthlessly flattened and it’s a shame, because I don’t know if this is entirely necessary. The narrators sentimentally and self-importantly capitalise the words “beauty”, “art”, and “humanity” but their intellectual posturing is soulless and regrettably anti-humanity and unbeautiful. They’re so deep in their heads that they’re not ruminating on the human condition at all— they use other people as sandpaper against which to sharpen their mean verbal acrobatics. This is so blatantly their point and I rolled my eyes when Renee called herself a prophet for contemporary times or whatever. What’s the point of endlessly contemplating beauty and art when you spend hours and hours overarticulating how other people are worthless? I was not impressed by their devotion to jasmine tea and camellias.

Reading about mean people is fun when the whole thing is graced with irony, when the author is so fully in on it. But the narrative voices of Paloma and Renee are so strikingly identical that I can’t help but feel that the author, Muriel Barbery, is writing with minimum effort, writing so close to her own heart that there isn’t much space for self-irony or self-parody. I could be wrong though.

I also took note of how Japan was depicted in this book— all hype, no depth. This contrasts with how Paloma conflates Asia with poverty in talking about a Thai boy adopted by a French family:

“And now here he is in France, at Angelina’s, suddenly immersed in a different culture without any time to adjust, with a social position that has changed in every way: from Asia to Europe, from poverty to wealth.”

I know she’s 12, but it struck me. Japan in this book is fetishised and immediately valued exclusively because of a handful of its cultural exports. Sushi, bonzai, haiku, Ozu, the traditional bow, and wabi-sabi are briefly mentioned. That’s all. What’s afforded is the Google-able iconography. The book goes no deeper, and the peppering of Japanese references did nothing to re-posture the characters, which is what it seemed to be going for.

Kakuro, the Japanese man introduced to change the narrator’s lives, was so thinly written. Extras in KDramas have received richer characterization. I was baffled as to why he, poised ummistakably as the pivotal character, was paper-thin and dimensionless, when the other characters were described with such precision albeit disdainfully. He “changes their lives” because the plot said so.

One last thing: this book was published in 2009, before discourse on mental health became more widespread. Words such as “anorexic”, “autistic”, and “retarded” are used a couple of times as adjectives, usually in derogatory contexts, which will date the book.

Man. I really wanted to like it.

Somewhat related recommendations:

“Pure Heroines”, an essay included in Jia Tolentino’s bestselling collection “Trick Mirror”. The essay explores the tropes performed by female literary characters, i.e. as children, they’re exceedingly crafty and prematurely disillusioned by their environment, and the plot hinges on how gloriously they can rewire themselves to escape it all; as teens, like Paloma, they’re angsty and hot and intellectual; and as grown women, they become casualties of certain institutions, such as religion, marriage, or what have you, and eventually kill themselves. Paloma, in this case, is a suicidal teenager. Interesting.

“The Dictionary of Animal Languages” by Heidi Sopinka. Also set in Paris. Also about an art-loving woman. Language is also somewhat florid but oftentimes delectable. Is a plotty book but doesn’t read as plotty, because it’s configured so diaristically. A sweet-smelling collection of painterly phrases.

0 notes