#Shawnee National Forest Preserve

Video

20160326KW-DSC_5980-Edit.jpg by Kevin Wang

1 note

·

View note

Text

What does it mean to be for a Place?

The following is a summary of a recent publication in Pacific Conservation Biology by a group of David H. Smith Conservation Research Fellows: Stephanie Borrrelle, Jonathan Koch, Caitlin McDonough MacKenzie, Kurt Ingeman, Bonnie McGill, Max Lambert, Anat Belasen, Joan Dudney, Charlotte Change, Amy Teffer, and Grace Wu. You can read the full article here.

When asked “Is protecting biological diversity and the ecosystems that support all life important to you?” most people would say “yes.” This is the work that conservation scientists like me and my friends do. We do things like figure out how to protect endangered bee species in Hawaiʻi (Koch), inform agencies how to manage the endangered whitebark pine in the Sierra Nevada (Dudney), and study how plants that grow on mountaintops in Maine are impacted by climate change (McDonough MacKenzie). However, many of us are not from the Places* we’re working to protect. In fact, many conservation scientists are descendants of colonizers and settlers (settler-colonizers) who removed, or benefited from the removal of Indigenous Peoples from these Places, which are their ancestral lands. Indigenous Peoples practicing diverse cultures lived for millennia in North America stewarding the land.

The Indigenous Peoples displaced by colonialism have distinct knowledges and cultural identities directly rooted in their lands. For example, Mauna Kea is more than a dormant volcano on the island of Hawaiʻi to the kānaka maoli (Native Hawaiians). The mountain is their biophysical and genealogical ancestor, a sacred site for cultural and spiritual activities. Another example is how Aboriginal Peoples in Australia practice cultural fire “for biodiversity, to protect the landscape, and for cultural reasons, all in one” (Steffensen 2019, p233).

Indigenous Peoples’ distinct genealogical and cultural relationship to the land and all the other beings they share the land with is far different than the relationship of settler colonizers to Place and nature. Industrial society is traditionally and intentionally very disconnected from nature, beginning with European states removing peasants from forests and the commodification of nature (Tsing 2005). For example, many of us don’t know where our food comes from; don’t have religious or cultural traditions connecting us to Place, the land, or nature; and don’t know the natural history of the creatures we encounter everyday.

So you can imagine it is more than awkward for settler-colonizer conservation scientists to be the only or dominant source of knowledge about how to conserve a colonized Place, yet for decades this has been a common occurrence. In some cases, conservationists have attempted to act as “white saviors” to local Peoples by centering the work around themselves and excluding local experts (see this piece about conservation in Africa by Mordecai Ogada). In other cases, settler-colonizer conservation has furthered the oppression of local Indigenous People by removing them from their homelands and calling them poachers when they hunt there (see this piece on US National Parks by Isaac Kantor). All with few long term conservation achievements to show for it—for evidence, look no further than the UN Convention on Biological Diversity. Turns out, preserving biodiversity is hard, as is adapting to climate change. At the local level, both of these issues require some global settler-colonial science as well as intimate knowledge of and human interaction with individual Places. I wonder who has that? ...

Some settler-colonizer/non-Indigenous conservation scientists are now beginning to listen to Indigenous knowledge keepers, collaborate on research with Indigenous groups, and, in some cases, supporting and following the lead of Indigenous managers of their ancestral lands and waters. Conservation scientists are beginning to understand that the only way to long term conservation successes is to develop conservation strategies that also support the social and physical wellbeing and self-determination of the people who live there. But these settler-Indigenous partnerships are built on a troubled history of colonial violence and oppression. So, how do settler-colonizer conservationists proceed in a way that does not perpetuate harms to Indigenous Peoples? In other words, what does it mean to be for a Place when you’re not from that Place?

Several of my scientist friends and I wrestled with this issue after visiting kia’i (protectors) of Mauna Kea (Mauna a Wākea). It was October 2019 and we were hosted by Moana “Ulu” Ching and Noelani Puniwai, both of whom are kānaka maoli, conservation scientists, and friends with one of us (Koch).

Noelani Puniwai and Moana “Ulu” Ching (far left) met with our group of Smith Conservation Fellows at Pu’u Huluhulu near the base of Mauna Kea. We sat on black lava rock from an old lava flow. (Photo by Joan Dudney)

We met at the bottom of the access road to the summit of Mauna Kea. Here was a tent community of kiaʻi protesting the construction of a new telescope called the Thirty Meter Telescope on the summit of their ancestral Mauna Kea. They were occupying the entry road to prevent construction vehicles from accessing the summit; 33 kupuna (Elders, grandparents, ancestors) were arrested several months earlier marking the escalating tensions between the kiaʻi and the governmental and private institutions involved in developing the Thirty Meter Telescope. The telescope is the continuation of colonialism on Mauna Kea sponsored by 11 nations and universities against the wishes of and providing little economic benefit to kānaka maoli. Not only does construction of a 14th research structure threaten the fragile ecosystems and endangered species at the summit of Mauna Kea, construction also perpetuates a long history of colonization in Hawaiʻi that threatens the cultural, economic, and ecological well being of kānaka maoli.

One of the tents at the protest site. The upside down American and Hawaiian flags represent the kānaka maoli rejection of these colonial powers. The upside down Hawaiian flag can be seen on cars and buildings throughout Hawai’i. (Photo by Joan Dudney)

We listened as Ulu and Noelani described their experiences and perspectives on Mauna Kea and the telescope. Afterward they invited us to participate in midday protocol, and we were humbled by the experience. Protocol is a sacred community building activity that happens every day and consists of oli (chants), pule (prayer), and hula (dance). Non-kānaka maoli were allowed to observe the protocol and were invited to participate in a certain part. We showed our respect to Mauna Kea by standing in our bare feet on the road to her summit for the protocol. In one hula we were sending our energy and strength to Mauna Kea.

As conservation scientists we wanted to show our solidarity with the kiaʻi. We wanted to voice our objections to the Thirty Meter Telescope in terms of conserving the fragile summit ecosystem, and equally important, call for an end to continued colonialist practices in the name of settler-colonizer science. We channelled this energy into a policy statement opposing the construction of the Thirty Meter Telescope on Mauna Kea, which was later adopted by the Society for Conservation Biology. We further reflected on the experience and wondered what first-hand learning we could share with other conservation scientists embarking on anticolonial conservation work. We came up with a series of recommendations for scientists. You can read all of them here. Here are three major ones:

Recognize the ways conservation theory and practice perpetuate the myth that North America was “empty” and “new” upon European “discovery.” For example, the mistaken belief that US National Parks never had human inhabitants despite the fact that Indigenous People have been living in and managing the lands and waters of North America for millennia.

Build authentic relationships with the Indigenous Peoples whose lands we are working on. Realize that settler-colonizer science is not the “correct” or only way of knowing.

Educate ourselves by learning about the history of the Places where we work and live and the Indigenous people affected by colonization. Read books and articles written by Indigenous scholars. Teach ourselves. After you have done the work to learn about the history and people(s), then reach out to Indigenous scholars, land stewards and managers.

We believe that being “for a Place” when you’re not from a Place means respect for Indigenous knowledge, continuous reflection on the consequences of our actions, and a willingness to act with humility, embrace complexity, and maintain hope. We are excited to grow and learn and contribute to the transformation of conservation science into a more inclusive, equitable, and just discipline.

*I capitalized Place throughout to emphasize its importance, akin to a person’s name being capitalized.

The Carnegie Museum of Natural History is on Seneca land and waterways, the homeland of the people we call the Monongahela, and lands and rivers used by and culturally connected to the Lenape, Shawnee, Wyandot, and Osage. I honor these ancestors, am grateful for their stewardship of these lands and waters, and acknowledge and respect their descendants alive today.

Bonnie McGill is a science communication fellow in the Section of Anthropocene Studies. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Work cited

Steffensen, V. 2019. Putting the people back into the country. In: Decolonizing Research: Indigenous Storywork as Methodology. J. Archibald Q’um Q’um Xiiem, J. B. J. Lee-Morgan, and J. De Santolo, eds. Zed Books (London).

Tsing, A. L. 2005. Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection. Princeton University Press (Princeton and Oxford).

#Carnegie Museum of Natural History#Place#Anthropocene#Science Writing#Scientific Research#Hawaii#Mauna Kea

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Little Miami Scenic State Park

8570 East State Route 73

Waynesville, Ohio 45068-9719 The Little Miami Scenic Park is located within the beautiful and historic Little Miami River Valley. The Little Miami is a designated federal and state scenic river. It is protected because of its high water quality, panoramic setting, and the many historic sites that can be found along its banks. The Little Miami State and National Scenic River offers a trip into one of Ohio's most beautiful and historic areas. As the river twists and bends, visitors will discover many natural wonders such as steep rocky cliffs, towering sycamores and elegant great blue herons on the wing. The Little Miami State and National Scenic River offers bikers and paddlers a trip into one of Ohio's most beautiful and historic areas. Visitors can traverse the 50-mile linear park by water, on the Little Miami State and Natural Scenic River, or on land via the Little Miami Scenic Bikeway Trail.

A trail meanders with the river through four counties encountering rolling farm country, towering cliffs, steep gorges and forests along the way. This steep gorge offers evidence of the erosional forces of glacial meltwater. Outcroppings of dolomite and shale are now exposed. Mammoth sycamores border the river's edge where great blue herons reside. Because of the relatively cool sheltered climate in the gorge, eastern hemlocks and Canada yew are able to survive here. Birdwatchers delight in the abundance and variety of colorful warblers and other songbirds in the park. The shaded slopes offer a variety of woodland wildflowers for visitors to enjoy. More than 340 species of wildflowers are known in the river's corridor. Virginia bluebells, bellworts, wild ginger and wild columbines are only a few to be seen in the park.

The Little Miami River Valley is historically significant to the state of Ohio. The wooded lands were home to several early Ohio Indian cultures. Nearby are the largest and best known earthworks in the state known as Fort Ancient. Fort Ancient was built by the Hopewell Indians who inhabited the area from 300 B.C. to 600 A.D. In more recent history, this area was inhabited by the Miami Indians and the Shawnee. After the War of 1812, the Indian threat dissipated and the area attracted settlers. Numerous mills were developed on the river bank and several still stand today. Clifton Mill near Yellow Springs is still in operation. By the mid 1800s, the river corridor was bustling with grist mills, textile mills, stagecoach trails and a railroad line. Indian mounds and relics, historic buildings, grist mills and stagecoach trails can still be found in this historic river valley. The Little Miami Scenic Park became a state park in 1979.

Camping is limited along the developed portion of the trail. Several privately operated canoe liveries along the river offer camping for those backpacking or hiking long stretches of the river corridor. Other overnight accommodations can be found in the various bed and breakfast locations and motels in Lebanon, Morrow, Loveland and Milford. Smallmouth and rock bass provide excellent catches for anglers. Fishing is permitted from boats and from shore at the canoe access sites. A valid Ohio fishing license is required. Two picnic areas with shelterhouses are offered at the staging sites along the route. One area is in Morrow, the other is in Loveland. The shelterhouses are available on a first-come, first-served basis. Little Miami State Park introduces a new concept to the state park system--a trail corridor. This non-traditional approach focuses on offering numerous recreational pursuits--bicycling, hiking, cross-country skiing, rollerblading, backpacking and horseback riding. The corridor also provides access to canoeing the Little Miami River.

From the northernmost canoe access point to the Ohio River, the Little Miami River can provide numerous levels of excitement: an historic journey, an environmental experience, a fishing or recreational trip. The Little Miami River is approximately 105-miles long, of which nearly 86 miles are canoeable. Those who plan to canoe or boat the Little Miami Scenic River must exercise caution because the river's immense power is often hidden. All rivers may become dangerous when water is high and flow is rapid from heavy rainfall. Streams such as the Little Miami are always dangerous at lowhead dams and where log jams or submerged trees create powerful forces in the current. Approved, properly fitting life jackets are required. All boats and canoes require a current registration sticker.

Little Miami State Park is approximately 50 miles in length. It averages 66 feet in width and runs through four counties of southwest Ohio (Greene, Warren, Clermont and Hamilton). This abandoned railroad right-of-way, converted for public use, boasts 47 miles of paved trail from Milford to Hedges Road. The remainder of the trail to Springfield is paved and operated by Greene County Parks and Recreation. Three staging areas (Loveland, Morrow and Corwin) have been located along the developed portion of the park. These include parking lots, restrooms, public phones and trail access points. These facilities are wheelchair accessible.

Three state parks are nearby including Caesar Creek in Waynesville, East Fork in Bethel (both taking their names from branches of the Little Miami), and John Bryan near Yellow Springs, Ohio. All three parks offer camping, hiking and fishing opportunities. Two state nature preserves, Clifton Gorge and Caesar Creek Gorge are close by. Both preserves offer unique geological and botanical features for visitors to enjoy. Spring Valley Wildlife Area operated by the ODNR Division of Wildlife offers hunting and fishing opportunities for sportsmen and is also known as one of the best birdwatching areas in southwestern Ohio. A boardwalk leads to a wildlife observation tower over the marsh. Caesar Creek also has a wildlife area available for hunting. Kings Island Amusement Park, located at Kings Mill, Ohio and Loveland Castle both offer interesting side trips in the area.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Biogeography of unique shade-loving, cliff-dwelling French’s shootingstar of the central hardoowds forests of North America, and its isolated presence in Alabama:

Photo 1: French’s Shootingstar - Dodecatheon frenchii - under a sandstone overhang in Shawnee National Forest, southern Illinois. (Source.) Photo 2: A colony of the plant in typical habitat under an overhang at Devil’s Hollow in Cane Creek Canyon Nature Preserve in Alabama. (Source.)

Text from R. Scot Duncan’s Southern Wonder: Alabama’s Surprising Biodiversity:

Within the deep canyons of Little Mountain is found French’s Shootingstar, a lovely little plant whose presence in northwestern Alabama is linked to an ancient coastline. Early each spring, the shootingstar emerges from dormancy and grows low to the ground. By late spring, older plants will develop a thin stalk several inches long on which hang several delicate flowers. At the base of each petal is a strip of deep maroon bordered in yellow, but the rest of the petal is an immaculate white turning pink with age. The flower strongly recurves its petals skyward while aiming its pistil and stamens downward. As the name suggests, the overall display could resemble a meteorite streaking earthward.

However, these shootingstars will never see the sky, for they live exclusively beneath the lip of sandstone overhangs provided by the Cumberland Acidic Cliff and Rockhouse ecosystem. Why the shootingstar lives here is clear: light is so scarce and the soils can be so dry that virtually no other vascular plants vie for this habitat. What’s more, the rockhouse protects the plants from erosion and being smothered by the thick mats of leaf litter accumulating on the forest floor just a few feet away. [...] How rockhouses came to be in [northern Alabama] takes us back to 340 million years ago [...] when [...] the area that is now the Southwestern Appalachians [...] was a shallow tropical sea. [...] Just offshore, sands accumulated as a chain of barrier islands like those along the Gulf Coast. This island chain became a thick rock formation dubbed the Harstelle Sandstone.

The Pride Mountain and Hartselle Sandstone formations breach the surface of northern Alabama in several locales, but nowhere as prominently as in the Little Mountain ecoregion of the Interior Plateau. [...] The dry, sandy soils on the caprock sustain the Southern Interior Low Plateau Dry-Mesic Oak Forest that was once widespread in [the Deep South’s interior plateau region]. [...] The most intriguing ecosystems of Little Mountain occupy the valleys and canyons weaving through these hills. These sheltered slopes harbor another variation of the [the Deep South’s wetter interior mesophytic forests] and hundreds of animals and plants rare elsewhere in the Southeast. Among them are orchids, lilies, azaleas, American Ginseng, Goldenseal, American Columbo, Bosch’s Filmy Fern, Eastern Leatherwood, and Kentucky Yellowood, to name a few. [...] There’s so much plant diversity that plant enthusiasts return to Little Mountain year after year. The rockhouse homes of French’s Shootingstar occupy the steepest slops of Little Mountains canyons. They form because [...] softer and lower rocks of Pride Mountain Formation erode first, while the upper and harder Harstelle Sandstone yields more slowly. These differential rates of erosion create the overhangs. [...]

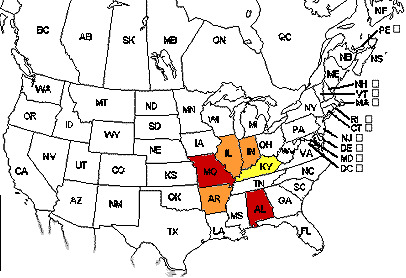

French’s Shootingstar is known from Arkansas and four Midwestern states, but its presence in Alabama is a biogeographical puzzle. None of Alabama’s neighboring states have populations. What’s more, Alabama’s only population is on Little Mountain, despite the proximity of rockhouses a dozen miles away in the Dissected Plateau ecoregion. For whatever reason, this little plant survives in Alabama thanks to those barrier islands from long, long ago.

The Shooting Star Cliffs of Perry County and Crawford County, Indiana, featuring some ecological communities more similar to Appalachia rather than the “typical” Heartland. (Source.)

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

woodland trails sussex

charles e burchfield nature & art center

sunshine park

wendt beach park

mill road park

kinzua rail viaduct

five mile park tucumcari

five mile park tucumari pool

cazenovia creek wildlife management area

harlem road park

dorrance park

switzer park

hillery park

brookdale park

children's memorial park

raymond park

honeycrest playground

dartwood park

orchard acres park

eiffel park

cheektowaga volunteer firemen's park

bailey peninsula natural habitat park

greenway nature trail

keysa park

heritage trail

meadow lea park

westwood park

walden pond park

port dalhousie waterfront trail

cranberry lake preserve

kenneglenn scenic and nature preserve

orchard hill nature center

dater mountain nature park

shagbark nature park

hunters creek county park

walker's creek

bell slip

dufferin islands nature area

rolin t grant gulf wilderness park

rosberg family park

larkin woods/franklin gulf

stevensville conservation area

golden orchard park

canal valley

rouge valley conservation center

wilma quinlan nature preserve

orchard hills park

merritt island park

niagara regional native center

victoria junction

humberstone marsh conservation area

siamese ponds wilderness

green ribbon trail

heartland forest nature experience

louth conservation area

larry delazzer nature park

marcy's woods

rouge national urban park

mud lake conservation area

heaven hill trails

rockway conservation area

tillman road wildlife management area

great baehre swamp wildlife management area

ellicott creek trail way park

hunters creek county park

walton woods park

swallow hollow

tow path park

darien lakes state park

tonawanda wildlife management area

tinker nature park/hansen nature center

panama rocks scenic park

turkey hill overlook trail

chimney bluffs state park

midway state park

great baehre conservation park

pop warner rail trail

laclair kindel wildlife sanctuary

ricketts glen

falls trail benton pa

delaware water gap national recreation area

shoshone park

hudson highlands state park

tucquan glen nature preserve

whitewater challengers

george w child's park

lytle nature preserve

shawnee state park

french creek state park

birdsong parklands

union canal tunnel park

hickory hollow natural area preserve

bushy run battlefield

sodus point new york

codorus state park

elizabeth a morton national wildlife refuge

woodward cave

friends of memorial lake and swarta state parks

mason dixon trail

conewago recreation trail

houghton park

kaaterskills falls trail head

storm king state park

frank e jadwin memorial state forest

abandoned restrooms lafayette square

shelton square comfort station

lafayette square comfort station

ps 75 abandoned

j.n. adam memorial hospital

sattler theatre

rail yard through tifft

jackson sanatorium

gallagher beach

gallagher beach silo

buffalo audubon society

town of lockport nature trail

abandoned roswell springville

witchs grave south of springville on the road walmart is on

buildings at intersection of west ave & tonawanda st near niagara

abandoned brylin in alden

ward road and niagara falls boulevard bell aircraft

perry projects abandoned

south long beach

kings park psychiatric center

floyd bennett field

clarence escarpment sanctuary

fort tilden

fort totten

flooded gypsum mines around old peanut line clarence

onondaga escarpment caves

landstone drive mansion abandoned clarence

blackrock/riverside train tracks

clarence bike path

abandoned buffalo china building

clarence nature center

bassett park

75 hayes place buffalo

abandoned art deco train terminal

the gel mac silo

abandoned millard fillmore gates hospital

delta reservoir

castle on the hill/physical culture hotel in dansville

doodletown

elko quaker bridge

love canal

concrete central elevator

southwick beach state park

ray bay

lake erie beach

split rock falls

otter falls

stony kill falls

vernooy falls

enfield falls

buttermilk falls

dunkley falls

bournes beach

the old sea plane ramp at lasalle park

murder creek

new ireland

frontier town schroon lake

rt. 77 lewiston road east of alabama

bethlehem steel lackawanna plant

onoville

kinzua dam

oswego new york hamlet

parksville

red house

iron island museum

venus fountain statue wolcott

worlds largest pancake griddle penn yan

central terminal buffalo

mount st mary's nursing home niagara falls

hh richardson complex

niagara falls police station ontario

st ann's cathedral buffalo

toronto power generating station ontario

mutual riverfront park

penn dixie fossil park & nature preserve

gorcica field

chestnut ridge park commissioner's cabin

eagle crest

seneca bluffs

erie county forest

buffalo harbor state park

wilkeson point

knox farm state park

eighteen mile creek lake

mountain meadows park

elma meadows park

hunters creek county park

como lake park

broderick park

lake erie beach park

windmill point park

ellicott creek park

westwood park

meadow lea park

hobuck flats

colden lakes resort

black rock canal park

town of orchard park skate park

beaver island golf course

town of sardinia music in the park

oppenheim county park

hyde park

reservoir state park

southtown salt cave

knights hide-away park

brook gardens

0 notes

Photo

Best Things To Do in Cuyahoga Valley National Park

Best Things To Do in Cuyahoga Valley National Park: Though it's only a short distance from the urban areas of Cleveland and Akron, Cuyahoga Valley National Park seems worlds away. The park is a refuge for native plants and wildlife, and provides routes of discovery for visitors. The winding Cuyahoga River gives way to deep forests, rolling hills, and open farmlands. Walk or ride the Towpath Trail to follow the historic route of the Ohio & Erie Canal. You can fish, golf and even enjoy skiing and snowboarding! My name is Rob Decker and I'm a photographer and graphic artist with a single great passion for America's National Parks! I've been to 48 of our 61 National Parks — and Cuyahoga Valley is a great place to visit - regardless of the time of year! Cuyahoga Valley is unusual in that it is adjacent to two large urban areas and includes a dense road network, small towns, and private attractions. I have explored much of the park — so I'm ready to help! If this is your first time to the park, or your returning after many years, here are some of the best things to do in Cuyahoga Valley National Park! Ride the Scenic Train The National Park Scenic Railway is a unique way to experience all the natural wonder Cuyahoga Valley National Park. Sit back and relax as the train weaves through the Cuyahoga Valley and races along with the rushing Cuyahoga River. Look for eagles, deer, beavers and otters in their natural habitat. From January-May, the National Park Scenic excursion is a two-and-a-half hour round trip through Cuyahoga Valley National Park. Board at Rockside Station, Peninsula Depot, or at Akron Northside Station. From June through October, the train runs Wednesdays-Sundays on an extended schedule. You can choose from a variety of seating options including coach, table top, first class, lounge, upper dome, executive class, or suites. Hiking You can hike more than 125 miles of trails in Cuyahoga Valley National Park that range from nearly level to challenging. ,Pass through various habitats including woodlands, wetlands, and old fields. Some trails require you to cross streams with stepping stones or log bridges, while others, including the Ohio & Erie Canal Towpath Trail, are nearly level and are accessible to all visitors. A portion of Ohio's Buckeye Trail also passes through the park. Biking Biking the Towpath Trail This multi-purpose trail was developed by the National Park Service and is the major trail through Cuyahoga Valley National Park. Mountain Biking The East Rim Trail System has stunning views, varied terrain, exciting obstacles, and an element of adventure for anyone who explores it. Bike and Hike Aboard Bike or hike the Towpath Trail in one direction and hop on the train on your way back! The train can be flagged down at boarding stations by waving both arms over your head. You should arrive 10 minutes prior to the train's scheduled arrival...and you can pay your fare when you board. Visit the Beaver Marsh The Beaver Marsh is among the most diverse natural communities in Cuyahoga Valley National Park. The exceptional scenery and wildlife make it one of the park's most popular destinations. Here you can enjoy photography, bird watching, and sharing nature with family and friends. Enjoy Brandywine Falls Brandywine Falls is one of the most popular locations in the park. This 65-foot waterfall is accessed via a partially accessible boardwalk. For a more challenging trip, take the steep stairs to the lower viewpoint or the 1.4-mile Brandywine Gorge Trail. Hike or Picnic at The Ledges The Ritchie Ledges are witnesses to change - from creation out of Sharon Conglomerate millions of years ago, to landscapes wrecked by humans and to preservation today. The Civilian Conservation Corps created the park you see today, building trails and shelters throughout the area. Explore Blue Hen Falls This 15-foot waterfall is a beautiful hike every time of year. There is a small parking lot located across the street from the main trailhead. From there, the falls are a steep half-mile hike. Fishing The Cuyahoga River and numerous ponds are open to fishing. Cuyahoga Valley National Park's philosophy is to maintain the predator-prey relationship rather than to stock fish for recreational fishing. Catch-and-release fishing is encouraged to maintain the fish populations needed for continued sport fishing. The park has over 65 species of fish that live in its waters. Steelhead trout and bullhead can be caught in the Cuyahoga River. Bluegill, bass, and crappie can be caught in lakes and ponds in the park. Kayaking and Canoeing People who want to canoe or kayak the Cuyahoga River in Cuyahoga Valley National Park need to bring their own equipment and have experience to manage the safety risks posed by the river. The National Park Service does not maintain the river for recreational use. Canoeing and kayaking the river can be dangerous. Water quality, low head dams, and debris in the river all pose hazards. Horse Riding Viewing the Cuyahoga Valley landscape from horseback is like no other experience. Horseback riding is permitted only on trails signed and designated as horse trails. Horses need to be brought in as there are no horse rentals adjacent to the bridle trails. Try Your Hand at Canalway Questing Find more than 40 adventures—called quests—along the Ohio & Erie Canal! Put on your sleuthing hat and follow rhyming clues and a curious map to each hidden quest box. Along the way, discover the area's treasures—the natural and cultural gems of the Canalway. Unlike geocaching, no GPS unit is needed and no trinkets are exchanged. When you find a quest box, collect its unique stamp, sign its logbook, and put it back in place for others to discover. Golfing Cuyahoga Valley National Park offers the unique opportunity for golfing within the park, although none of the golf courses are federally owned or operated. You can golf at any of the following courses: Astorhurst Country Club Brandywine Golf Course Shawnee Hills Golf Course Sleepy Hollow Golf Course I've created a poster to celebrate Cuyahoga Valley National Park that features the famous Brandywine Falls. The poster can also be purchased at the Conservancy for Cuyahoga Valley National Park shops in the park! Click here to see the Cuyahoga Valley National Park poster. Rob Decker is a photographer and graphic artist with a single passion for our National Parks! Rob is on a journey to explore and photograph each of our national parks and to create WPA-style posters to celebrate the amazing landscapes, vibrant culture and rich history that embody America's Best Idea! Click here to learn more about Rob & the National Park Poster Project! https://national-park-posters.com/blogs/national-park-posters/best-things-to-do-in-cuyahoga-valley-national-park?utm_source=rss&utm_medium=Sendible&utm_campaign=RSS

0 notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Story of Charles Willson Peale’s Massive Mastodon

https://sciencespies.com/nature/the-story-of-charles-willson-peales-massive-mastodon/

The Story of Charles Willson Peale’s Massive Mastodon

SMITHSONIANMAG.COM |

May 6, 2020, 10:44 a.m.

In the 18th century, French naturalist George-Louis Leclerc, Comte du Buffon (1706-1778), published a multivolume work on natural history, Histoire naturelle, générale et particuliére. This massive treatise, which eventually grew to 44 quarto volumes, became an essential reference work for anyone interested in the study of nature.

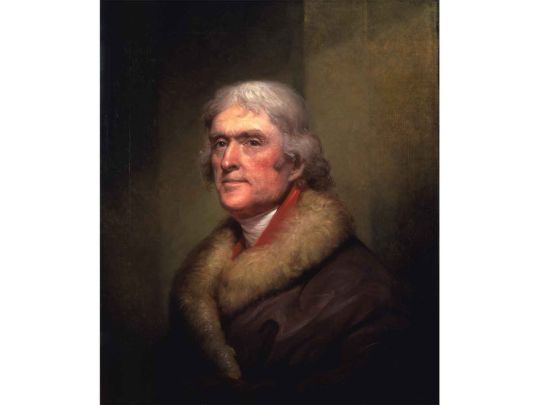

The Comte de Buffon advanced a claim in his ninth volume, published in 1797, that greatly irked American naturalists. He argued that America was devoid of large, powerful creatures and that its human inhabitants were “feeble” by comparison to their European counterparts. Buffon ascribed this alleged situation to the cold and damp climate in much of America. The claim infuriated Thomas Jefferson, who spent much time and effort trying to refute it—even sending Buffon a large bull moose procured at considerable cost from Vermont.

While a bull moose is indeed larger and more imposing than any extant animal in Eurasia, Jefferson and others in the young republic soon came across evidence of even larger American mammals. In 1739, a French military expedition found the bones and teeth of an enormous creature along the Ohio River at Big Bone Lick in what would become the Commonwealth of Kentucky. These finds were forwarded to Buffon and other naturalists at the Jardin des Plantes (the precursor of today’s Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle) in Paris. Of course, the local Shawnee people had long known about the presence of large bones and teeth at Big Bone Lick. This occurrence is one of many such sites in the Ohio Valley that have wet, salty soil. For millennia, bison, deer and elk congregated there to lick up the salt, and the indigenous people collected the salt as well. The Shawnee considered the large bones the remains of mighty great buffalos that had been killed by lightning.

An infuriated Thomas Jefferson (above: 1805 by Rembrandt Peale) spent much time and effort trying to refute Buffon’s claim—even sending him a large bull moose procured at considerable cost from Vermont.

(New York Historical Society)

Later, the famous frontiersman Daniel Boone and others, such as the future president William Henry Harrison, collected many more bones and teeth at Big Bone Lick and presented them to George Washington, Ben Franklin and other American notables. Sponsored by President Thomas Jefferson, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark also recovered remains at the site, some of which would end up at Monticello, Jefferson’s home near Charlottesville, Virginia.

Meanwhile in Europe, naturalists were initially at a loss of what to make of the large bones and teeth coming from the ancient salt lick. Buffon and others puzzled over the leg bones, resembling those of modern elephants, and the knobby teeth that looked like those of a hippopotamus and speculated that these fossils represented a mixture of two different kinds of mammals.

Later, some scholars argued that all the remains might belong to an unknown animal, which they called “Incognitum.” Keenly interested in this mysterious beast and based on his belief that none of the Creator’s works could ever vanish, Jefferson rejected the notion that the Incognitum from Big Bone Lick was extinct. He hoped living representatives were still thriving somewhere in the vast unexplored lands to the west.

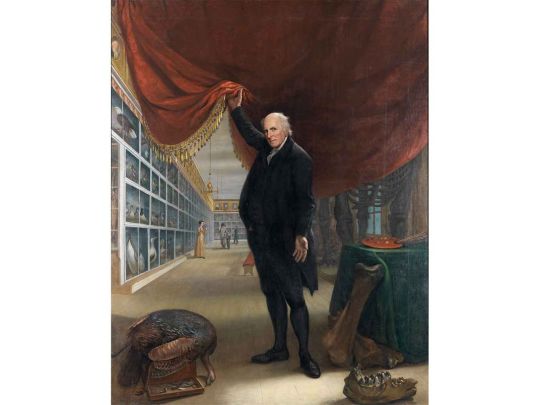

Charles Willson Peale, well-known for his portraits had a keen interest in natural history and so he created his own museum (above: The Artist in His Museum by Charles Willson Peale, 1822).

(Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, gift of Mrs. Sarah Harrison)

In 1796, Georges Cuvier, the great French zoologist and founder of vertebrate paleontology, correctly recognized that Incognitum and the woolly mammoth from Siberia were likely two vanished species of elephants, but distinct from the modern African and Indian species. Three years later, the German anatomist Johann Friedrich Blumenbach assigned the scientific name Mammut to the American fossils in the mistaken belief that they represented the same kind of elephant as the woolly mammoth. Later, species of Mammut became known as mastodons (named for the knob-like cusps on their cheek teeth).

By the second half of the 18th century, there were several reports of large bones and teeth from the Hudson Valley of New York State that closely resembled the mastodon remains from the Ohio Valley. The most noteworthy was the discovery in 1799 of large bones on a farm in Newburgh, Orange County. Workers had uncovered a huge thighbone while digging up calcium-rich marl for fertilizer on the farm of one John Masten. This led to a more concerted search that yielded more bones and teeth. Masten stored these finds on the floor of his granary for public viewing.

News of this discovery spread fast. Jefferson immediately tried to buy the excavated remains but was unsuccessful. In 1801, Charles Willson Peale, a Philadelphia artist and naturalist, succeeded in buying Masten’s bones and teeth, paying the farmer $200 (about $4,000 in today’s dollars) and tossing in new gowns for his wife and daughters, along with a gun for the farmer’s son. With an additional $100, Peale secured the right to further excavate the marl pit.

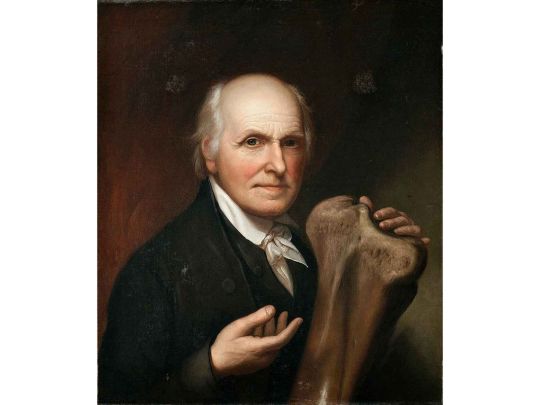

In 1801, Peale (above: Self-Portrait with Mastodon Bone, 1824) succeeded in buying Masten’s bones and teeth, paying the farmer $200 (about $4,000 in today’s dollars) and tossing in new gowns for his wife and daughters, along with a gun for the farmer’s son.

(New York Historical Society)

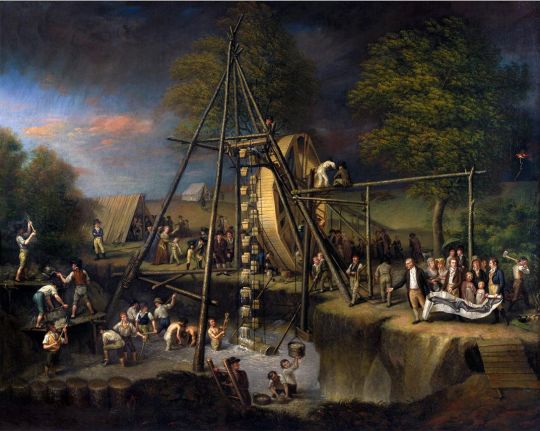

To remove water from the site, a millwright constructed a large wheel, so that three or four men walking abreast could provide the power to move a chain of buckets that bailed out the pit using a trough leading to a low-lying area of the farm. Once the water level had dropped sufficiently, a crew of workers recovered additional bones in the pit. In his quest to get as many bones and teeth of the mastodon as possible, Peale acquired additional remains from marl pits on two neighboring properties before shipping everything to Philadelphia. One of these sites, the Barber Farm in Montgomery, is today listed as “Peale’s Barber Farm Mastodon Exhumation Site” in the National Register of Historic Places.

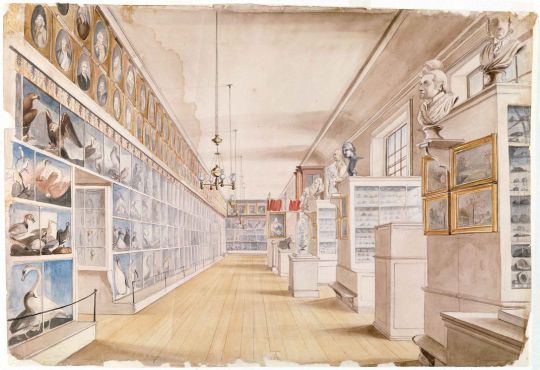

Peale, well-known for the portraits he had painted of several of the Founding Fathers as well as other prominent individuals, had a keen interest in natural history and so he created his own museum. A consummate showman, the Philadelphia artist envisioned the mastodon skeleton from the Hudson Valley as the star attraction for his new museum and set out to reconstruct and mount the remains for exhibition. For the missing bones, Peale crafted papier-mâché models for some and carved wooden replicas for others; eventually he reconstructed two skeletons. One skeleton was exhibited at his own museum—marketed on a broadside as “the LARGEST of Terrestrial Beings”—while his sons Rembrandt and Rubens took the other on tour in England in 1802.

Peale secured the right to further excavate the marl pit. To remove water from the site, a millwright constructed a large wheel, so that three or four men walking abreast could power a chain of buckets (above: Exhumation of the Mastodon by Charles Willson Peale, ca. 1806-08)

(Maryland Historical Society, gift of Bertha White)

Struggling financially, Peale unsuccessfully lobbied for public support for his museum where kept his mastodon. After his passing in 1827, family members tried to maintain Peale’s endeavor, but ultimately they were forced to close it. The famous showman P. T. Barnum purchased most of the museum’s collection in 1848, but Barnum’s museum burned down in 1851, and it was long assumed that Peale’s mastodon had been lost in that fire.

Fortunately, this proved not to be the case. Speculators had acquired the skeleton and shipped it to Europe in order to find a buyer in Britain or France. This proved unsuccessful. Finally, a German naturalist, Johann Jakob Kaup (1803-1873), bought it at a greatly reduced price for the geological collection of the Grand-Ducal Museum of Hesse in Darmstadt (Germany). The skeleton is now in the collections of what today is the State Museum of Hesse. In 1944, it miraculously survived an air raid that destroyed much of the museum, but which damaged only the mastodon’s reconstructed papier-mâché tusks.

Peale envisioned the mastodon skeleton as the star attraction for his new museum and set out to reconstruct and mount the remains for exhibition (above: The Long Room, Interior of Front Room in Peale’s Museum by Charles Willson Peale and Titian Ramsay Peale, 1822).

(Detroit Institute of Arts)

In recent years, Peale’s skeleton has been conserved and remounted based on our current knowledge of this extinct elephant. It stands 8.5 feet (2.6 meters) at the shoulder and has a body length, measured from the sockets for the tusks to the base of the tail, of 12.2 feet (3.7 meters). It has been estimated to be about 15,000 years old.

Mammut americanum roamed widely through Canada, Mexico and the United States and are now known from many fossils including several skeletons. It first appears in the fossil record nearly five million years ago and became extinct about 11,000 years ago, presumably a victim of changing climates following the last Ice Age and possibly hunting by the first peoples on this continent. Mastodons lived in open forests. A New York State mastodon skeleton was preserved with gut contents—pieces of small twigs from conifers such as fir, larch, poplar and willow—still intact.

This year Peale’s mastodon returns to her homeland to become part of the upcoming 2020 exhibition entitled “Alexander von Humboldt and the United States: Art, Nature, and Culture” at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Alexander von Humboldt had collected teeth of another species of mastodon in Ecuador and forwarded them to Cuvier for study. He also discussed them with Jefferson and Peale during his 1804 visit to the United States. The three savants agreed that Buffon’s claim concerning the inferiority of American animal life was without merit.

Currently, to support the effort to contain the spread of COVID-19, all Smithsonian museums in Washington, D.D. and in New York City, as well as the National Zoo are temporarily closed. The exhibition, “Alexander von Humboldt and the United States: Art, Nature, and Culture” will go on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in 2020.

#Nature

0 notes

Text

Not Content to Simply ‘Drink Local,’ These 8 Brewers Forage Ingredients from Nearby Lots, Yards, and Forests

As more brewers prioritize local ingredients and agriculture, a back-to-the-land ethos has become increasingly palpable in the beer industry. One way this philosophy has begun to resurface over the last decade is foraging, or searching for potable ingredients from one’s own property, nearby park or forest, or even neighbors’ backyards. Using ingredients harvested by hand, each foraged beer is a truly unique creation that brewers believe can enhance and encapsulate a sense of place.

Below are eight breweries hunting the local landscape for beer-friendly herbs, fruits, fungi, roots, and more raw ingredients for their foraged beers.

Fonta Flora

Morganton and Nebo, NC

Born in 2013 with a four-barrel brewhouse in downtown Morganton, N.C., Fonta Flora expanded its beer production with a nine-acre plot and 15-barrel brewhouse on Whippoorwill Farm, a former dairy farm near Lake James State Park in Nebo, N.C., in 2016. Along with foraging for ingredients for its beers, Fonta Flora hosts educational events and workshops so the public can join in on walking tours through the woods to find edible plants for future Fonta Flora products. Participants are eventually able to take home a bottle or 4-pack of the beer brewed after the hunt.

Forager Brewery / Humble Forager Brewery

Rochester, MN

Aptly named Forager Brewery, opened in 2015, recently announced it will launch a new brand in 2020, Humble Forager Brewery. “We decided to do it because of the constant calls and demands to get our beer into bars, liquor stores, and restaurants,” Austin Jevne, co-founder and brewer, told Growler magazine. The brand was created “as a workaround to Minnesota’s brewpub laws.” At present, its “scratch kitchen” and brewery offers seasonal dishes and beers made with local fruits, honeys, and grains.

Fullsteam Brewery

Durham, NC

Founded in 2010, Fullsteam Brewery emphasizes agricultural and culinary traditions of the “post-tobacco South” with beers like Farm’s Edge: Brumley Forest, made with ingredients foraged in Brumley Forest. A portion of proceeds is given back to the non-profit that maintains the public nature preserve.

Highland Park Brewery

Los Angeles, CA

L.A.’s Highland Park Brewery, opened in 2015, is known for its fun, funky brews like its Twiced Jura Blend, a farmhouse-style saison fermented in French oak puncheon barrels with house-mixed cultures along with spent whole-cluster Pinot Noir, Gamay, and Trousseau grapes from nearby Whitecraft Winery of Santa Barbara. Recently, Highland Park collaborated with Allagash Brewing on a pilsner made with local California grains and hops.

Scratch Brewing Company

Ava, IL

Scratch, located five miles from the Shawnee National Forest, is one of the small breweries that put foraged beer on the map, albeit from a fairly remote location. It aims to showcase “Southern Illinois terroir” with its beer (and pizza!) made with foraged ingredients like nettle, elderberry, ginger, maple sap, and chanterelle mushrooms. A majority of Scratch’s beers are sold in its taproom in Ava, Ill., as well as the newer Serpent Room opened in 2017. A select amount is distributed in-state and to a few neighboring states.

Urban Farm Fermentory

Portland, ME

“Fermentor” and culinary rising star Eli Cayer founded Urban Farm Fermentory in 2010. The fermentory produces beer, cider, mead, kombucha, and jun with foraged ingredients from Cayer’s home state of Maine. “Foraging is a huge part of what we do,” Urban Farm Fermentory says on its website. “Through foraging, we’re able to highlight what is growing seasonally as it’s still in season.” Beers include Lavender Lager and Saison de Gruit, a Belgian-style farmhouse ale made with bitter herbs instead of hops.

West Kill Brewing

West Kill, NY

West Kill Brewing recently celebrated a 2019 Great American Beer Festival win for its Kaaterskill IPA, but juicy brews aren’t all brewmaster Patrick “P.J.” Allen excels in. Working on a farm brewery in New York’s Catskill region, Allen utilizes the 127-acre property to forage unusual ingredients like knotweed for his rotating and “seasonally dependent” beers. Forsaken Fields, a mixed-culture saison with creeping thyme and spruce tips from the brewery’s surroundings, is currently on tap. The farm brewery also produces its own maple syrup.

Wunderkammer Bier

Greensboro Bend, VT

Hill Farmstead head brewer and production manager Vasilios Glestos started Wunderkammer as a homebrewing project and now produces his (extremely limited) foraged beers to sell. One release, From the Ruins of a Subterranean Feasting Hall, is made with mixed cultures along with cedar, spruce, fir, and pine tips foraged in Vermont.

The article Not Content to Simply ‘Drink Local,’ These 8 Brewers Forage Ingredients from Nearby Lots, Yards, and Forests appeared first on VinePair.

source https://vinepair.com/articles/foraged-beer-breweries/

0 notes

Text

Not Content to Simply ‘Drink Local,’ These 8 Brewers Forage Ingredients from Nearby Lots, Yards, and Forests

As more brewers prioritize local ingredients and agriculture, a back-to-the-land ethos has become increasingly palpable in the beer industry. One way this philosophy has begun to resurface over the last decade is foraging, or searching for potable ingredients from one’s own property, nearby park or forest, or even neighbors’ backyards. Using ingredients harvested by hand, each foraged beer is a truly unique creation that brewers believe can enhance and encapsulate a sense of place.

Below are eight breweries hunting the local landscape for beer-friendly herbs, fruits, fungi, roots, and more raw ingredients for their foraged beers.

Fonta Flora

Morganton and Nebo, NC

Born in 2013 with a four-barrel brewhouse in downtown Morganton, N.C., Fonta Flora expanded its beer production with a nine-acre plot and 15-barrel brewhouse on Whippoorwill Farm, a former dairy farm near Lake James State Park in Nebo, N.C., in 2016. Along with foraging for ingredients for its beers, Fonta Flora hosts educational events and workshops so the public can join in on walking tours through the woods to find edible plants for future Fonta Flora products. Participants are eventually able to take home a bottle or 4-pack of the beer brewed after the hunt.

Forager Brewery / Humble Forager Brewery

Rochester, MN

Aptly named Forager Brewery, opened in 2015, recently announced it will launch a new brand in 2020, Humble Forager Brewery. “We decided to do it because of the constant calls and demands to get our beer into bars, liquor stores, and restaurants,” Austin Jevne, co-founder and brewer, told Growler magazine. The brand was created “as a workaround to Minnesota’s brewpub laws.” At present, its “scratch kitchen” and brewery offers seasonal dishes and beers made with local fruits, honeys, and grains.

Fullsteam Brewery

Durham, NC

Founded in 2010, Fullsteam Brewery emphasizes agricultural and culinary traditions of the “post-tobacco South” with beers like Farm’s Edge: Brumley Forest, made with ingredients foraged in Brumley Forest. A portion of proceeds is given back to the non-profit that maintains the public nature preserve.

Highland Park Brewery

Los Angeles, CA

L.A.’s Highland Park Brewery, opened in 2015, is known for its fun, funky brews like its Twiced Jura Blend, a farmhouse-style saison fermented in French oak puncheon barrels with house-mixed cultures along with spent whole-cluster Pinot Noir, Gamay, and Trousseau grapes from nearby Whitecraft Winery of Santa Barbara. Recently, Highland Park collaborated with Allagash Brewing on a pilsner made with local California grains and hops.

Scratch Brewing Company

Ava, IL

Scratch, located five miles from the Shawnee National Forest, is one of the small breweries that put foraged beer on the map, albeit from a fairly remote location. It aims to showcase “Southern Illinois terroir” with its beer (and pizza!) made with foraged ingredients like nettle, elderberry, ginger, maple sap, and chanterelle mushrooms. A majority of Scratch’s beers are sold in its taproom in Ava, Ill., as well as the newer Serpent Room opened in 2017. A select amount is distributed in-state and to a few neighboring states.

Urban Farm Fermentory

Portland, ME

“Fermentor” and culinary rising star Eli Cayer founded Urban Farm Fermentory in 2010. The fermentory produces beer, cider, mead, kombucha, and jun with foraged ingredients from Cayer’s home state of Maine. “Foraging is a huge part of what we do,” Urban Farm Fermentory says on its website. “Through foraging, we’re able to highlight what is growing seasonally as it’s still in season.” Beers include Lavender Lager and Saison de Gruit, a Belgian-style farmhouse ale made with bitter herbs instead of hops.

West Kill Brewing

West Kill, NY

West Kill Brewing recently celebrated a 2019 Great American Beer Festival win for its Kaaterskill IPA, but juicy brews aren’t all brewmaster Patrick “P.J.” Allen excels in. Working on a farm brewery in New York’s Catskill region, Allen utilizes the 127-acre property to forage unusual ingredients like knotweed for his rotating and “seasonally dependent” beers. Forsaken Fields, a mixed-culture saison with creeping thyme and spruce tips from the brewery’s surroundings, is currently on tap. The farm brewery also produces its own maple syrup.

Wunderkammer Bier

Greensboro Bend, VT

Hill Farmstead head brewer and production manager Vasilios Glestos started Wunderkammer as a homebrewing project and now produces his (extremely limited) foraged beers to sell. One release, From the Ruins of a Subterranean Feasting Hall, is made with mixed cultures along with cedar, spruce, fir, and pine tips foraged in Vermont.

The article Not Content to Simply ‘Drink Local,’ These 8 Brewers Forage Ingredients from Nearby Lots, Yards, and Forests appeared first on VinePair.

source https://vinepair.com/articles/foraged-beer-breweries/

source https://vinology1.wordpress.com/2019/10/22/not-content-to-simply-drink-local-these-8-brewers-forage-ingredients-from-nearby-lots-yards-and-forests/

0 notes

Text

Not Content to Simply Drink Local These 8 Brewers Forage Ingredients from Nearby Lots Yards and Forests

As more brewers prioritize local ingredients and agriculture, a back-to-the-land ethos has become increasingly palpable in the beer industry. One way this philosophy has begun to resurface over the last decade is foraging, or searching for potable ingredients from one’s own property, nearby park or forest, or even neighbors’ backyards. Using ingredients harvested by hand, each foraged beer is a truly unique creation that brewers believe can enhance and encapsulate a sense of place.

Below are eight breweries hunting the local landscape for beer-friendly herbs, fruits, fungi, roots, and more raw ingredients for their foraged beers.

Fonta Flora

Morganton and Nebo, NC

Born in 2013 with a four-barrel brewhouse in downtown Morganton, N.C., Fonta Flora expanded its beer production with a nine-acre plot and 15-barrel brewhouse on Whippoorwill Farm, a former dairy farm near Lake James State Park in Nebo, N.C., in 2016. Along with foraging for ingredients for its beers, Fonta Flora hosts educational events and workshops so the public can join in on walking tours through the woods to find edible plants for future Fonta Flora products. Participants are eventually able to take home a bottle or 4-pack of the beer brewed after the hunt.

Forager Brewery / Humble Forager Brewery

Rochester, MN

Aptly named Forager Brewery, opened in 2015, recently announced it will launch a new brand in 2020, Humble Forager Brewery. “We decided to do it because of the constant calls and demands to get our beer into bars, liquor stores, and restaurants,” Austin Jevne, co-founder and brewer, told Growler magazine. The brand was created “as a workaround to Minnesota’s brewpub laws.” At present, its “scratch kitchen” and brewery offers seasonal dishes and beers made with local fruits, honeys, and grains.

Fullsteam Brewery

Durham, NC

Founded in 2010, Fullsteam Brewery emphasizes agricultural and culinary traditions of the “post-tobacco South” with beers like Farm’s Edge: Brumley Forest, made with ingredients foraged in Brumley Forest. A portion of proceeds is given back to the non-profit that maintains the public nature preserve.

Highland Park Brewery

Los Angeles, CA

L.A.’s Highland Park Brewery, opened in 2015, is known for its fun, funky brews like its Twiced Jura Blend, a farmhouse-style saison fermented in French oak puncheon barrels with house-mixed cultures along with spent whole-cluster Pinot Noir, Gamay, and Trousseau grapes from nearby Whitecraft Winery of Santa Barbara. Recently, Highland Park collaborated with Allagash Brewing on a pilsner made with local California grains and hops.

Scratch Brewing Company

Ava, IL

Scratch, located five miles from the Shawnee National Forest, is one of the small breweries that put foraged beer on the map, albeit from a fairly remote location. It aims to showcase “Southern Illinois terroir” with its beer (and pizza!) made with foraged ingredients like nettle, elderberry, ginger, maple sap, and chanterelle mushrooms. A majority of Scratch’s beers are sold in its taproom in Ava, Ill., as well as the newer Serpent Room opened in 2017. A select amount is distributed in-state and to a few neighboring states.

Urban Farm Fermentory

Portland, ME

“Fermentor” and culinary rising star Eli Cayer founded Urban Farm Fermentory in 2010. The fermentory produces beer, cider, mead, kombucha, and jun with foraged ingredients from Cayer’s home state of Maine. “Foraging is a huge part of what we do,” Urban Farm Fermentory says on its website. “Through foraging, we’re able to highlight what is growing seasonally as it’s still in season.” Beers include Lavender Lager and Saison de Gruit, a Belgian-style farmhouse ale made with bitter herbs instead of hops.

West Kill Brewing

West Kill, NY

West Kill Brewing recently celebrated a 2019 Great American Beer Festival win for its Kaaterskill IPA, but juicy brews aren’t all brewmaster Patrick “P.J.” Allen excels in. Working on a farm brewery in New York’s Catskill region, Allen utilizes the 127-acre property to forage unusual ingredients like knotweed for his rotating and “seasonally dependent” beers. Forsaken Fields, a mixed-culture saison with creeping thyme and spruce tips from the brewery’s surroundings, is currently on tap. The farm brewery also produces its own maple syrup.

Wunderkammer Bier

Greensboro Bend, VT

Hill Farmstead head brewer and production manager Vasilios Glestos started Wunderkammer as a homebrewing project and now produces his (extremely limited) foraged beers to sell. One release, From the Ruins of a Subterranean Feasting Hall, is made with mixed cultures along with cedar, spruce, fir, and pine tips foraged in Vermont.

The article Not Content to Simply ‘Drink Local,’ These 8 Brewers Forage Ingredients from Nearby Lots, Yards, and Forests appeared first on VinePair.

Via https://vinepair.com/articles/foraged-beer-breweries/

source https://vinology1.weebly.com/blog/not-content-to-simply-drink-local-these-8-brewers-forage-ingredients-from-nearby-lots-yards-and-forests

0 notes

Photo

A Royal Tour of Pennsylvania

From actual castles to Gothic-style mansions, Pennsylvania has many examples of majestic architectural wonders to explore and learn the history behind their construction.

Travel back in time to before the Industrial Revolution at Fonthill Castle and Mercer Museum. Designed as archaelogist and tile maker Henry Mercer Chapman's home and showcase for his exquisite collection of tiles and prints. The castle features 44 rooms with built-in furniture, hand-crafted ceramic tiles, artifacts from Chapman's world travels and over 6,000 books. The Mercer Museum displays exhibits from the arts and crafts movement and tools Mercer collected to preserve the era.

Nemacolin Castle, also known as Bowman’s Castle, was built to house Jacob Bowman’s nine children and his trading post. Throughout the 1800s it was expanded into the 22-room castle it is today. It was named for Nemacolin's Trail, named after the Shawnee chief who helped improve and mark the ancient Native American trail through the Alleghenies.

Dedicated to educating about the history of religion, Glencairn Museum originally served as a home for the Pitcairn family. The castle-like mansion displays more than 10,000 historical objects. Mainly religious in nature, the objects are from ancient Egypt and Greece, and the Roman Empire. Also inside are Early Medieval stained glass windows and a replica of the Biblical tabernacle. The nine-story, granite-and-ruddy-colored-stone mansion features more than 90 rooms on 10 floors.

Completed in 1894, the 72-acre Woodmont Manor House is a mansion and hilltop estate operated by the International Peace Mission Movement. In 1953, it became the home of evangelist Father M.J. Divine and the center of his International Peace Mission movement. It was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1998 for its well-preserved Chateau-style architecture.

Grey Towers was built by the father of Gifford Pinchot, the 28th Governor of Pennsylvania and first chief of the United States Forest Service. The Pinchot family's summer home was designed to reflect their French heritage. The mansion, a three-story L-shaped fieldstone chateau, has conical roofed towers at three of the corners which give the property its name.

Built in the heart of the University of Pennsylvania’s campus in the 1890s, the Fisher Fine Arts Library features towering staircases, stained-glass windows, high ceilings and a fortress-like exterior. The red sandstone, brick-and-terra-cotta Venetian Gothic giant - part fortress and part cathedral - was built to be the primary library of the University and to house its archaeological collection. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the Library has been declared a National Historic Landmark.

Contact Colonial Capital Tours to plan your royal tour of Pennsylvania's castles.

🗺Colonial Capital Tours

☎️ 800.334.3754

💻 www.ColonialCapitalTours.com

📧 [email protected]

#pennsylvaniacastles #castles #glencairn #visitpa #royaltourofcastles #historyteachers #daytrips #studenttours #educationaltours #schooltrips #fieldtrips #studentgroups #schoolgroups #grouptours #nycdoe #nycdoevendor #doe #multidaytrips #studenttrips #educationalprograms #colonialcapitaltours

0 notes

Text

Not Content to Simply ‘Drink Local,’ These 8 Brewers Forage Ingredients from Nearby Lots, Yards, and Forests

As more brewers prioritize local ingredients and agriculture, a back-to-the-land ethos has become increasingly palpable in the beer industry. One way this philosophy has begun to resurface over the last decade is foraging, or searching for potable ingredients from one’s own property, nearby park or forest, or even neighbors’ backyards. Using ingredients harvested by hand, each foraged beer is a truly unique creation that brewers believe can enhance and encapsulate a sense of place.

Below are eight breweries hunting the local landscape for beer-friendly herbs, fruits, fungi, roots, and more raw ingredients for their foraged beers.

Fonta Flora

Morganton and Nebo, NC

Born in 2013 with a four-barrel brewhouse in downtown Morganton, N.C., Fonta Flora expanded its beer production with a nine-acre plot and 15-barrel brewhouse on Whippoorwill Farm, a former dairy farm near Lake James State Park in Nebo, N.C., in 2016. Along with foraging for ingredients for its beers, Fonta Flora hosts educational events and workshops so the public can join in on walking tours through the woods to find edible plants for future Fonta Flora products. Participants are eventually able to take home a bottle or 4-pack of the beer brewed after the hunt.

Forager Brewery / Humble Forager Brewery

Rochester, MN

Aptly named Forager Brewery, opened in 2015, recently announced it will launch a new brand in 2020, Humble Forager Brewery. “We decided to do it because of the constant calls and demands to get our beer into bars, liquor stores, and restaurants,” Austin Jevne, co-founder and brewer, told Growler magazine. The brand was created “as a workaround to Minnesota’s brewpub laws.” At present, its “scratch kitchen” and brewery offers seasonal dishes and beers made with local fruits, honeys, and grains.

Fullsteam Brewery

Durham, NC

Founded in 2010, Fullsteam Brewery emphasizes agricultural and culinary traditions of the “post-tobacco South” with beers like Farm’s Edge: Brumley Forest, made with ingredients foraged in Brumley Forest. A portion of proceeds is given back to the non-profit that maintains the public nature preserve.

Highland Park Brewery

Los Angeles, CA

L.A.’s Highland Park Brewery, opened in 2015, is known for its fun, funky brews like its Twiced Jura Blend, a farmhouse-style saison fermented in French oak puncheon barrels with house-mixed cultures along with spent whole-cluster Pinot Noir, Gamay, and Trousseau grapes from nearby Whitecraft Winery of Santa Barbara. Recently, Highland Park collaborated with Allagash Brewing on a pilsner made with local California grains and hops.

Scratch Brewing Company

Ava, IL

Scratch, located five miles from the Shawnee National Forest, is one of the small breweries that put foraged beer on the map, albeit from a fairly remote location. It aims to showcase “Southern Illinois terroir” with its beer (and pizza!) made with foraged ingredients like nettle, elderberry, ginger, maple sap, and chanterelle mushrooms. A majority of Scratch’s beers are sold in its taproom in Ava, Ill., as well as the newer Serpent Room opened in 2017. A select amount is distributed in-state and to a few neighboring states.

Urban Farm Fermentory

Portland, ME

“Fermentor” and culinary rising star Eli Cayer founded Urban Farm Fermentory in 2010. The fermentory produces beer, cider, mead, kombucha, and jun with foraged ingredients from Cayer’s home state of Maine. “Foraging is a huge part of what we do,” Urban Farm Fermentory says on its website. “Through foraging, we’re able to highlight what is growing seasonally as it’s still in season.” Beers include Lavender Lager and Saison de Gruit, a Belgian-style farmhouse ale made with bitter herbs instead of hops.

West Kill Brewing

West Kill, NY

West Kill Brewing recently celebrated a 2019 Great American Beer Festival win for its Kaaterskill IPA, but juicy brews aren’t all brewmaster Patrick “P.J.” Allen excels in. Working on a farm brewery in New York’s Catskill region, Allen utilizes the 127-acre property to forage unusual ingredients like knotweed for his rotating and “seasonally dependent” beers. Forsaken Fields, a mixed-culture saison with creeping thyme and spruce tips from the brewery’s surroundings, is currently on tap. The farm brewery also produces its own maple syrup.

Wunderkammer Bier

Greensboro Bend, VT

Hill Farmstead head brewer and production manager Vasilios Glestos started Wunderkammer as a homebrewing project and now produces his (extremely limited) foraged beers to sell. One release, From the Ruins of a Subterranean Feasting Hall, is made with mixed cultures along with cedar, spruce, fir, and pine tips foraged in Vermont.

The article Not Content to Simply ‘Drink Local,’ These 8 Brewers Forage Ingredients from Nearby Lots, Yards, and Forests appeared first on VinePair.

source https://vinepair.com/articles/foraged-beer-breweries/

source https://vinology1.tumblr.com/post/188515647394

0 notes