#Raincoastgamer

Photo

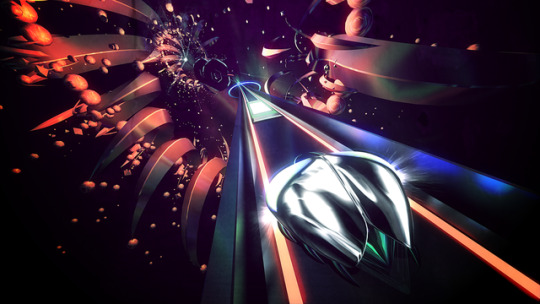

Thumper, by Drool. Available on Windows and PS4. Compatible with Oculus VR and PSVR (VR is optional).

Rhythm is a central part of our existence as breathing human beings with functioning hearts. There’s a rhythm in the movement of the planets, which dictates the rhythm of the seasons; the slow annual rhythm of a forest which pumps sap into dead wood every spring. There’s a rhythm inside every living creature, not only in the breath and heartbeat but also in the pulse of electrical charge which drives thought and movement. There’s a reason why percussion is the oldest form of music in the world; we are naturally tuned to find rhythms. Attempt to disrupt a beat and you’ll probably find yourself simply creating a new pattern. Syncopation is, after all, simply the intentional disruption of a rhythm to create the desired effect. Rhythms don’t have to be perfectly paced 4/4 affairs. I’m fond of the driving, eternal forward stumble of the 7/8 rhythm myself.

That’s probably the reason why a good many video games out there are based on rhythm. We have the Guitar Hero and Rock Band games made by Harmonix, the indie music-parser games like Audiosurf and Beat Hazard, DDR-style dance pad games, Crypt of the Necrodancer, Osu, a myriad of mobile games like Cytus and Deemo, and many, many more that I’ve probably never even heard of. Even games that aren’t focussed on music can have a rhythmic element to them at some deep, instinctual level. When playing Bloodborne I’ve found that there’s a sort of deliberate rhythm of dodge, strike, and parry when you fight NPC hunters, and that’s when the game is at its best. Rhythm and music, rhythm and action, these are familiar by now. Rhythm horror, though? That’s a new one.

Thumper has no jumpscares, and though the survival aspect of survival horror is very present this isn’t a slow and methodical creep-around-corners-and-hide-in-closets journey. Thumper is fast and deadly and violent in a metallic and bloodless but terribly visceral way. Thumper deals in the horror of the unknown, a Lovecraftian insignificance amidst the cosmos horror. Here you’ll find the creeping dread of uncertainty, of knowing that no matter how strange and unsettling the things just got, what comes next is probably going to be worse in a way that you can’t possibly foresee. This is probably why Thumper is a little difficult to describe.

You’re a metal beetle, eternally careening along a rail through a hellish void to the sound of thumping, crashing rhythm and electronic drones. The music is difficult to classify as anything that I’ve heard before, mostly percussion. This is fitting considering that one of the developers is ex-Harmonix artist Brian Gibson, the bassist for the noise rock duo Lightning Bolt. The things that you witness on your journey, pointed tentacles and abstract shapes, reflect the darkly-colored void like chrome plating yet move in a disconcertingly organic manner. Sometimes you speed between rows of waving, angular antennae. Occasionally you encounter some strange, otherworldly entity, some fractal thing made out of raw, folded firmament. Each of the game’s nine levels concludes by confronting a giant, increasingly twisted and inhuman skull. H.P. Lovecraft would likely use the word ‘cyclopean’ to describe what goes on in Thumper, though he’d be hard pressed to make any sort of racial metaphors with it. Sparks fly and the screen shakes when you hit corners and break barriers, and the combined music and sound effects fill every wavelength the aural spectrum to complete the utter sensory overload. ‘Rhythm violence’ is the tagline used by the developers, Drool, to describe Thumper, and it fits oh so well.

None of this really captures the full extent of what it is to actually play Thumper. Perhaps we can start again with the controls. It’s simple: one button and four directions. Your beetle will encounter glowing panels on the rail. Press the button when you pass over to create a bass thump. Holding the thump button tucks your shiny beetle body tighter into the track and lets you safely grind around turns and break through barriers. Two levels into the game, you learn that you can leap into the air to hover over spike traps and hit floating rings to snag more points. Three levels in, you’re taught to slam back down onto the thump pads while you’re in the air, sending a wave of distortion down the track. You’d do this to break the barriers some bosses will put up, and to create combos for more points if your timing is good. Later on, the rail will occasionally split into multiple lanes. You’ll need to flit between lanes to hit thumps and dodge obstacles, and jump back onto the right lane when they recombine into one. The controls are simple and the pace at which the game introduces new mechanics is gentle. It’s very easy to pick up and play, but from around Level 4 onwards Thumper takes the kid gloves off and cranks the intensity to the max.

Fortunately, it’s possible to simply survive your way through this game. Perfection isn’t required to progress, and, besides, perfection is difficult to achieve at the speed at which Thumper moves. Missing the thumps might cause you to lose your combo, but it won’t kill you. Running into a corner without turning in the right direction or hitting an obstacle, on the other hand, deals damage. In later levels a ring will occasionally appear around the track for short periods of time, zapping you with lasers if you miss a thump. The first hit causes you to lose your outer shell. The second hit kills you. Each of the game’s nine levels is divided into a number of sections, with checkpoints between. You respawn at a checkpoint when you die, so while the game does get very tough near the end it’s got a certain amount of leniency when it comes to progression. But then you encounter a boss, an entity of some kind which blocks your way forward. Are these things manifestations of the twisted space itself, are they beings running along the rail in front of you, or are they creating the rail moment by moment, placing the obstacles in your way as their only form of self-defense? Either way, now you’re required to hit all the thump pads in a segment of track that will begin repeating itself until you either get the pattern right or die. Thump all the pads in a segment and you get a special, brightly-glowing one that causes you to fire a blast of energy at the boss. Rinse and repeat until the boss disintegrates into a wash of debris.

The mere mechanics of the game don’t really do it justice either. The tight and simple controls are part of the whole thing, certainly, but it’s the game’s unrelenting aesthetic crossed with responsive controls, a visceral sense of feedback, the sheer sense of speed and, most importantly, a rock-solid understanding of rhythm that makes it all work. The beats that you, the player, the beetle are hitting aren’t necessarily going to be “on the beat” with the music. The developer duo Drool know how to play with a rhythm, how to syncopate, sub-divide, and subvert a beat. The thumps, slams, slides and ticks that the player makes as they speed along the track overlay and then weave into not only the background drones and beats but also the sounds that the various obstacles make as they appear on the track. There’s an important element of call-and-response to this game, with the various obstacles signaling their presence a (musical) bar before you need to react to them. In later levels the nearly-subconscious recognition of these aural cues is essential as obstacles come fast and thick, the track itself twisting, turning and obscuring obstacles until the last moment. It might even be possible to play this game with your eyes closed, though I personally wouldn’t attempt it.

The moment that Thumper really clicked for me, though, was when I returned to earlier levels to replay them with the knowledge and reflexes I’d learned from later levels. It was when I started really playing the earlier levels, not simply surviving them, that I started feeling a mix of apprehension, elation and flow. Thumper is possibly the only rhythm game in the world to make me feel like I was actually performing live music. Performing live music is to pour everything you have into a brief period of time in which everything could go wrong. Preparation can only take you so far. When you’re performing you are not only turning rote-remembered skills into a form of self-expression, you’re reacting and adjusting to your instrument and the performances of other performers moment by moment. Thumper creates that feeling by reducing nearly everything to percussion, thus tying all the sounds the player makes to the game’s simple controls. Playing Thumper means creating a piece of music which corresponds directly to your actions. Thumper builds on this by giving the player leeway to add their own flair, to increase risk and reward by adding aerial thumps and going for perfect turns. The beat will go on whether or not you hit all the cues, but there is a satisfaction in not only playing your part of the music but playing it well. You hear what seemed like a series of random obstacles turn into an entirely new section of the soundtrack, performed by you.

Some might express disappointment that Thumper doesn’t offer the sort of endless replayability that a game like Audiosurf provides. Thumper can’t dynamically parse custom music files, but, really, that misses the point of Thumper. Every element of Thumper, from the oppressive soundtrack to the placement of every obstacle to the responsive controls to the stark and alien visuals is designed to create a singular experience. The end result is something strange and unsettling. Thumper doesn’t gently coax the player into a flow state, it instead pushes you onto the edge of the precipice and challenges you to thrive there. The game may only require gentle taps and presses, but I’d find my thumb getting sore partway through a level through sheer tension and wouldn’t even notice until the level finished. I wouldn’t recommend playing for extended periods of time unless you want your arms to lock up out of stress. The mounting fear of what comes next is countered by the demands imposed by Thumper’s speed. You either focus and become one with the beat, reacting to and perhaps even overcoming everything the void throws at you, or else you crash and explode. You may never fully understand the hows, whys, whats and wheres of your situation, but you can still plunge into that abyss and master the rhythm. Perhaps you might even find some sort of meaning in the act of thumping itself.

Oh, and high scores. There’s a leaderboard for each level and all sorts of little nuances to eking out a high score, just in case you didn’t feel intimidated enough by the hellish void. If you like pushing your thumbs and reflexes to the limit, that’s for you.

Tune in next time when Taihus dedicates his life to the glory of mankind.

-Taihus “I am a space beetle hurtling towards infinity; shiny and chrome” @raincoastgamer

#Video Games#gaming#Reviews#Review#Thumper#Drool#VR#Raincoastgamer#A Rain Coast Gamer's Ramblings#Taihus#The Oblivian Studios#Oblivian Studios#Oblivian

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Red and the Transistor commission for @raincoastgamer !

I don’t know much about this game, but drawing these two was really fun!

386 notes

·

View notes

Text

Micro-Ramble: Hyper Light Drifter

Hyper Light Drifter, by Heart Machine. Available on Windows, OS X, Linux, Xbox One, PS 4, Ouya.

Having played through the game once, I can’t really find much to say that hasn’t been said already. I’ll keep this short.

It’s extremely pretty in just about every way. The pixel art style works well, the sprite animations are detailed and expressive, and the soundtrack by Disasterpeace is atmospheric and moody and hits all the right notes. The color palette of pastels, purples and greens creates a distinct and beautifully alien aesthetic that recalls its influences while being recognizably Hyper Light Drifter.

I can see why some people are then rather distressed about how this game actually plays. The atmosphere which the game creates suggests a quiet and moody exploration game, but the combat is a fast and precise affair that emphasizes timing, movement and the ability to juggle both ranged and melee combat. Some people have likened it to Dark Souls, and I’d personally compare it to something more along the lines of Bloodborne, what with a lack of purely defensive options.

As an aside, I want to give my sincerest thanks and congratulations to the brave programmers who updated Hyper Light Drifter to run at 60 frames a second. I don’t know what kind of technical wizardry you worked to make a Gamemaker game run at 60fps, but the effort was well worth it.

Dark Souls/Bloodborne is an interesting comparison, and a bit of a controversial one. Instead of going back and forth on whether or not it’s valid, I think I’ll just point out why I think some people make the mental connection. First off, Dark Souls has a lot of Zelda in its genes. Exploration in a big world full of secret corners and puzzles is an important part of both, and if anything HLD is one of the few true Zelda-like games to come out... ever, really. Secondly, HLD is pretty difficult. Combat encounters are demanding, and many secrets require perseverance, great observation and deduction skills, occasional leaps of faith and even manual dexterity when it comes to the dash-timing puzzles. Like Dark Souls, Hyper Light Drifter is a game about overcoming the challenges of an uncaring, brutal world. It simply wouldn’t be able to convey the oppressive nature of the protagonist’s journey if the game were easier. Third, neither game is very forthright with its story. Both the Soulsborne games and HLD are more concerned with an overall mood and themes communicated mostly through an opening cinematic, environmental details, and the process of playing the game itself. There’s a story if you’re willing to spend time and energy digging into the clues which the game gives you, but it’s not necessary to enjoy the experience and soak in the ambiance.

Finally, I just want to recognize that Hyper Light Drifter is very strongly influenced by an anime movie called Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind. This movie is considered by many fans of Studio Ghibli to be a sort of unofficial Ghibli movie; it was directed by Hayao Miyazaki and was what made the formation of the studio possible. A strange and colorful post-apocalyptic world, plus a non-specific apocalypse which involved giant, artificial beings whose remains can still be seen littered around the landscape are both signature elements of HLD and Nausicaa. I’d even go so far as to say that the ends of both HLD and the manga version of Nausicaa (which goes deeper into the characters and the world, is more epic in scope, but is perhaps just a bit too self-indulgent by the end) strike similar thematic and emotional notes.

All in all, a beautifully conceived and constructed game. Though perhaps not for anyone who wants a perfectly relaxing mood piece, or perhaps something with less combat and more puzzles, it’s a good title if you like fast and challenging combat crossed with the mood and atmosphere set by the game’s trailers.

Tune in next time when I turn into a space beetle and thump a rhythm beyond time and space.

-Taihus “Hyper Light Driftest” @raincoastgamer

#hyper light drifter#heart machine#gaming#rpg game#indie game#kickstarter#Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind#game ramble#game review#ramble

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Game Ramble: Helldivers is Other People

Helldivers, developed by Arrowhead Studios, published by Playstation Mobile, Inc. Available on PS4 and Windows (Steam).

It’s interesting how I started playing Helldivers just this year, as the climate of North American politics becomes ever more absurd. Interesting because Helldivers is “Starship Troopers: The Game” in all but name. Not Starship Troopers, the novel, but rather the Verhoeven movie which satirized everything from fascist ideology to Hollywood’s idea of battle strategy to military propaganda films. Like all good satire a good many people failed to see the joke, but that’s another story. Luckily for us, Helldivers’ satire is very on-the-nose with its vainglorious musical themes, the defense of Democracy for Super Earth™, and various Helldiver vocal barks such as “How d’you like the taste of democracy?!”, “Freedom delivery!” and “Have a nice cup of liber-TEA!”. Taking Helldivers seriously is like taking any aspect of the Warhammer 40000 setting seriously. Indeed Helldivers does seem to have some 40k in its rather Imperial Guard skulls-and-fascism aesthetic.

The fact that I’ve only begun to play Helldivers in the recent few months is also interesting because the game is extremely focused on cooperative multiplayer, and my friends are three time zones away from me. I’ve had to mostly play Helldivers with random strangers, and while I’ve had some great moments of team triumph and disaster, it’s really not the same as experiencing those kinds of moments with friends. Helldivers’ co-op nature won’t be a surprise to anyone who has played Arrowhead Studios’ claim to fame: a little game called Magicka, in which a team of between one and four incompetent wizards try to save the world. Part of what made that game tick was the spell casting system; you controlled your wizard using a top-down Diablo-like control scheme, and you could combine eight different magical elements on the fly in various quantities and combinations to create spells. Learning various spell combinations and unleashing over-the-top displays of elemental death was a big portion of the game. Either that, or you’d accidentally leave a crucial element out of a spell and set yourself on fire, or electrocute yourself, or heal an enemy instead of disintegrate them, or... well, let’s just say that there’s a reason Magicka is known to many as the Mage Suicide Simulator.

The other thing that made the game tick was other players, since spells could interact with other spells, and there was no option to turn friendly fire off. Fire a beam of healing energy and if it accidentally touched your friend’s arcane death beam it would create an explosion, probably hurling your friend off a cliff. Cast a bubble shield to keep everyone safe while your friend is firing a blast of electricity and the energy would ricochet around inside the bubble, zapping everyone. What kept it from turning into a rage-fest were a couple of things. Firstly, the revive spell was very easy to cast even while you were being mobbed by enemies and it would bring all your dead friends back to life immediately. Secondly, a team of wizards who knew what they were doing would become a force of nature, combining elemental effects to devastating effect. Occasionally even a competent team of wizards would self-destruct in spectacular fashion (my “favorite” is “exploding circle of electrified arcane ice walls”. That’s right, Thegiant, I’m talking to you), but the results are generally as hilarious as they are explosive.

Helldivers, then, is a decent if finicky top-down shooter when played solo, but truly shines when you start playing it with others. It takes a little more nuance to play than you might expect from the seemingly standard twin-stick shooter template. Weapons have a fairly small amount of ammunition per magazine, the number of magazines you can carry is limited, reloading takes a long time, and whatever ammunition was left in your magazine when you reload is dropped forever. It’s the kind of thing you’d expect from a simulation-focused game like ARMA, not from a twin-stick shooter. On top of this, your character can equip four “stratagems” - air support and special equipment dropped from orbit. These are called in by pressing a sequence of direction keys, a system which is a little reminiscent of the famous Konami code. Completing the sequence correctly gives your character a beacon which they then throw like a grenade. The stratagem will then arrive at the beacon’s location: generally a pod containing the requested equipment, landing at terminal velocity from space. As this is a game from the people who made Magicka, the pod (or airstrike, or vehicle) will kill anything it lands on. The contents of the stratagem usually need to be treated with care as well, since things like turrets and airstrikes will not care if you happen to be in the way. They won’t deliberately target you, but a turret can and will shoot anything that’s between itself and its target. All in all, at this point Helldivers is a game that requires some finesse to play, but doesn’t seem all that special. In fact, a lot of the things it does seem like small inconveniences for the sake of inconveniencing the player.

And then comes the point at which you call in some friends or strangers, or join someone else’s mission in progress. On the easier missions, what usually happens next is pure chaos. Friendly fire is once again a reality of life, not an option to be turned off. It’s easy enough to call in dead friends as reinforcements from orbit, but the stratagem beacon is damnably imprecise, and its resemblance to a grenade means that all too many people will throw it at a mob of enemies. Then again, the pod you arrive in will kill anything it lands on, but that can also include the guy who dropped the respawn beacon in the first place. Being killed by your own friends is a reality in Helldivers, even by complete accident. Even something as simple as waiting for the shuttle to pick you up at the end of the mission can become deadly as people start calling in spare mech suits, extra turrets, landmines and airstrikes whether they’re actually needed or not. The shuttle itself will crush anyone incautious enough to be standing under it when it arrives.

But then you play enough games with the same group or with your friends, you start playing harder missions, and something magical happens: everyone starts working as a team. You start noticing how entire systems of the game are built to encourage, nay, require cooperative play. The camera itself, locked into a top-down view which forces all four players to be on the screen at once, ensures that everyone is always moving as a team. The risk of friendly fire means that everyone instinctively starts moving in staggered formations and will maintain clear cones of fire. Simply calling in an essential stratagem can take time and attention away from incoming enemies, and having friends to cover you when you’re stratagem-ing and reloading your gun is enormously helpful. Since each player can only bring four stratagems into a mission, this encourages specialization. One player might use two slots for mech suits so she has a spare if one is destroyed or runs out of ammo. Another player brings a personal shield generator and a repair gun to act as the engineer. Another one brings turrets and barbed wire. The fourth brings a variety of heavy weapon options.

Many weapons and vehicles themselves flat out work better if you’re playing with a team. Simply wielding a lot of the heavy weapons keeps you stationary, so you’re relying on teammates to watch your back. Mech suits turn slowly and have a weak point in the rear, so it’s a good idea for other players to keep enemies off of the flanks. The APC has huge blind spots in its firing angles unless a full team of four are manning all the turrets. The rocket launchers in Helldivers come with a support pack which carries all the spare ammunition. The player using the rocket launcher can carry the support pack themselves and reload their weapon solo, but this takes several seconds during which they’re immobile. If another player carries the support pack and reloads the launcher for their friend when prompted, however, this only takes about half a second. A team of players who know what they’re doing can bring a truly impressive amount of firepower to bear, and are all the more impressive for the fact that this represents a lot of trust, communication and genuine teamwork between them.

The final thing that makes Helldivers a blast to play is the way that the game throws in small bits of chaos. Mainly these involve the inherent lack of precision when tossing out stratagem beacons crossed with the abundance and power of friendly fire. The finicky nature of a lot of this game’s mechanics at this point become points of failure, things that can and do go wrong when you’re under attack and just want to call in some more ammo, dammit! Small crises can cascade into larger crises, leading to panic and improvisation and the moments of triumph or disaster which make a good co-op action game shine. Two people reload at the same time, and suddenly cyborg dogs are eating your faces off. A stratagem beacon, thrown in the middle of a pitched fight, might bounce off a rock. Seconds later, your respawning friend arrives in a pod dropped from orbit and flattens your team’s APC. The guy piloting a mech suit might step backwards at the wrong moment and take off most of your health. One enemy patrol might wander in while you were dealing with a persistent tank, extending the engagement long enough for two more patrols to wander in, and then what was only a small, controlled engagement becomes a full on brawl. A turret might get placed just a few feet short of where you had meant to put it, and your friends were paying too much attention to the incoming wave of enemies to notice that they were between the turret and its targets. Like Magicka, the ease with which dead friends can be brought back means that death is mainly a source of comedy rather than a major setback. Like Magicka, it is when you’re teetering right at the edge of triumph or disaster with a dozen small things that could tip you either way that the game is really at its best.

A knife’s-edge of tension and a lot of balls to juggle isn’t required for all cooperative multiplayer games, but it certainly seems to be an important element of the shooter ones at least. Left 4 Dead’s Director AI was designed explicitly to keep players constantly on their toes, and the composition of later waves in Killing Floor is tuned to overwhelm the players unless they prioritize targets properly. The famous Nazi Zombies mode of the later Call Of Dutys kept players running around performing damage control by putting up barricades to keep the horde at a manageable level. Helldivers accomplishes the same thing by giving everyone a dozen things to do and get wrong at the same time, but compensates by keeping the price for each individual failure fairly small. A great mission in Helldivers is one in which each small crisis leads into another just as the previous one is resolved, and you don’t quite get the opportunity to recover and brace yourself for the next one. A great mission in Helldivers ends when the extraction shuttle lands on top of a giant alien bug and narrowly avoids crushing the player that the bug was about to eat. That player piles in just as another player dives out of the way of a badly placed strafing run and the third player sprints over from where he’d been taking cover next to his minigun turret and a pile of bug corpses. Finally, the shuttle takes off moments before the explosion of a nuclear bomb stratagem someone dropped just for the hell of it.

Tune in next time when Taihus thumps a rhythm somewhere out beyond the limits of sanity.

-Taihus “How about a nice cup of liber-TEA?!” @raincoastgamer

#Video Games#Gaming#The Oblivian Studios#Oblivian Studios#Raincoastgamer#A Rain-Coast Gamer's Ramblings#Game Ramble#Review#reviews#ramble#Helldivers#Magica#Arrowhead#Arrowhead Studios

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Card Ramble: Android: Netrunner

Android: Netrunner, produced by Fantasy Flight Games

Author’s plug: if you live in the Greater Toronto Area and want to get in touch with local Netrunner players, you can find us on the Torsaug City Grid facebook group. Netrunner players are a friendly bunch, so don’t be shy! If you let us know you’re a new player ahead of time, someone is guaranteed to bring along a couple of starter decks.

Author’s note: Well, this article is now going up three months or so after I had intended it to. Chalk it up to life getting in the way of actually playing the game I’m writing about.

I’ve become a little obsessed with Android: Netrunner. This is unusual for a number of reasons, not least of which are the facts that I’ve recently moved myself across the country to a place where I have no friends and don’t know the lay of the land. Also unusual is the fact that A:NR is a card game. With physical cards. That you have to buy and shuffle. Manually. With your hands.

Barbaric, I know.

I’m an inveterate inhabitant of the virtual world. A childhood spent convinced that the world was beneath me was followed by an adolescence catching up with social conventions and learning how to actually make friends. The net result is that I had never managed to actually get involved in any IRL gaming until very recently. Perhaps it is all for the best, since I didn’t end up with a Magic: The Gathering addition, even though I did briefly try to acquire one. Nowadays I’m not sure if Magic is the right game for me, though I can appreciate the genius of its design. Netrunner, on the other hand, has got me by the brainstem and refuses to let me jack out. I’ve taken to recommending Android: Netrunner to pretty much anyone on the off chance that they might like it. In fact, if you have a tendency of disliking Trading Card Games and their ilk (for example, say, Hearthstone) I’ll recommend this game to you even more.

This is because Android: Netrunner is guaranteed to be like nothing you’ve ever played. The main (and most obvious) reason I say this is because A:NR is completely asymmetrical. Each of the two players plays using a completely different set of cards and rules. You’d think that this would make A:NR into a solitaire game with only occasional interaction between players, yet I’ve seen few games outside of Poker or Bridge in which each player needs to pay so much attention to what their opponent is doing. Android:Netrunner is a game of skill and getting into the other guy’s head as much as it is a game of having the better deck, and I think it’s down to the fact that it’s a game not about hitting the other person with numbers but instead about either trying to steal the other person’s stuff, or trying to keep the other guy from stealing your stuff. More on that in a few paragraphs.

Magic has a certain, well, magic to its design. It’s approachable and easy to learn, with a fairly low number of options to consider on any given turn. Of course, once you buy a few booster packs the real depth of the game becomes apparent and opens into a bottomless pit, which is why a lot of game stores rely on sales of MtG booster packs and cards to pay the bills. The majority of that depth is in the construction of a deck, which is why acquiring good cards is such an important part of the game. A good deck plays itself, as they say, and a game of Magic can be won or lost from the first few moves. A game of Magic can even be won before the match starts, if the decks are particularly mismatched. Android: Netrunner is a bit trickier to learn than Magic, since mastering the turn-by-turn play of the game is just as important as the construction of a good deck. Nearly every turn is a calculated gamble, a balancing of the known facts and the possibilities, trying to get the person sitting across from you to slip up and tip their hand just one turn earlier or later than they should. Even towards the closing turns a game can be tipped one way or the other, and victory is rarely certain even on the turn when you win.

What’s interesting about A:NR’s design history is the fact that it was designed by none other than Richard Garfield, the designer of possibly the most-imitated TCG design in the world: Magic: The Gathering. Back in the 90’s, after creating the utter genius that was MtG, Mr. Garfield wanted to try designing something that would integrate the kind of information control and bluffing that was such an integral part of poker into a TCG. As he wrote, hidden information means that calculation and optimization can only take you so far before you have to start figuring out what the other person is up to. Your calculation might be flawed because the other person could be misleading you. Being able to read the other player’s loadout and setup would be just as important as a well-constructed deck, and even a bad situation could be turned around with some smart play and bluffing. Netrunner was the result, and was released as a TCG, like Magic, in 1996 and proceeded to get buried under the pile of other TCGs which were trying to copy Magic’s success. It got some cult recognition, people would occasionally say things like “oh, yeah, Netrunner was great, a pity they stopped printing it”, but it ultimately drowned. Today’s article is only possible thanks to Fantasy Flight Games, who bought the rights to Netrunner’s design in 2012, reprinting it with a few rule changes and integrating it into their own Android universe as Android: Netrunner.

I want to take a moment now to appreciate just how cyberpunk a name like Android: Netrunner is. I’m not sure how much more cyberpunk you can get. Say “Android: Netrunner”, and you might think of things like trench coats, cool shades, punk culture, cybernetics, mega-corporations, neural implants, urban sprawl, clones, the ethical dilemmas brought on by the fusion of man and circuitry and rampant capitalism.

So, perhaps in this shiny dystopian future you’d prefer the safety and security up on top of the pile. One of the two players in a game of Android: Netrunner is the Corporation, or Corp. This is your quintessential megacorporation, organizations with control over vast flows of information and the economies of nations at their beck and call. On their turn, the Corp player spends action points, called clicks, to place servers. These face-down cards represent mass marketing campaigns and resource processing operations, traps to punish an unwary intruder, or agenda cards representing the Corp’s plans. Private militaries and corporate takeovers. Psychic clones and putting your logo on the moon. Agenda cards are what win the game. The Corp devotes resources--credits and clicks--to place advancement tokens on their agenda cards. With enough advancement tokens the agenda card can be removed from the table, giving the corp points. If the corp reaches seven points, they win.

This being a cyberpunk world, all of these agendas and assets are accessible through the ‘net. To defend their servers from intrusion, Corporations deploy Intrusion Countermeasures, or Ice. These are nasty bits of software, standing guard against cyberspace intruders. The corp player spends clicks and credits to place Ice cards horizontally in layers in front of their servers. As the game progresses, the Corp uses more and more table space as they set up servers and reinforce their defences. A visual counterpoint to the Corp’s increasing power and influence.

Of course, you may not want to be a mere gear in the vast corporate machine. Maybe you want to show The Man what’s coming. Sitting across from the Corp is the titular Runner, a hacker/cracker who is the reason why the Corp needs all that Ice in the first place. The Runner plays with an entirely different deck, with cards representing their skills and resources instead of agendas and assets. Instead of building an array of servers and defenses, the Runner spends clicks and credits to build their rig, a set of cards which represents the runner’s programs, hardware and other resources such as underworld contacts, jobs, and contracts. Some Runners use the best software and hardware they can build. Some use favors called in to supply them with tools. Some call on blackmailed employees to get them into the system. And, of course, it wouldn’t be cyberpunk without the quintessential Punks with a capital P, taking it to the fat cats armed with the profits from a day job and all the brainpower a nap and an energy drink (Diesel: It gives you flames!) can give them, then running at the Corp using a computer jacked directly into their stimmed-up nervous system.

Once everything is ready or a weakness has been spotted, the Runner hacks into the Corp’s servers. This is called a run, and is quite probably why the game is called Netrunner. In game terms, the Runner chooses a server to run on, then encounters each piece of Ice on that server from the outside in. No matter the archetype, the most important parts of any Runner’s rig are icebreaker programs which allow them to spend resources to avoid the effects of any Ice they encounter while running. Some Ice may simply block access, bouncing the Runner out of the server, but some goes further: destroying software or even zapping the unfortunate intruder’s brain. Some Ice traces the intruder and then simply tags the Runner’s location in meatspace (good old non-virtual real life), which sounds like the softer option. That is, until you realize that the corporation may simply prefer to do things a bit more old-school by contracting some private security to search the runner’s home and make all their contacts disappear. In fact, better to just level the city block (and call it “urban redevelopment”), then freeze all their bank accounts.

Once the Runner gets through the Ice, they get to access the server’s contents. If the server contains an asset, they can spend credits to trash the card, forcing the Corp to discard a resource. If the server contains an agenda card, the Runner gets to steal it and takes the points. No mucking around with advancement tokens or anything like that; if the Runner grabs the agenda, they get the points. Like the Corp, if the Runner reaches seven agenda points they win.

The Corp wins by scoring seven points, and the Runner wins by stealing seven points. Simple, right? Not quite. This is where things get interesting. You see, everything that the Corp plays on the table is initially face-down, which includes their Ice defenses. The Corp doesn’t actually have to pay to rez, or activate, the Ice on a server until it is actually being approached by the Runner. That Ice could be a painful Neural Katana or lethal Archer, or it could just be a harmless Wall of Static. The server’s contents, too, are often a mystery. That face-down card could be a valuable 3-point agenda, or it could be a pad marketing campaign or even a trap that’s been advanced to make it look like an agenda.

The Corp’s ability to hide the true nature of their setup makes every run a calculated gamble, and changes the game from one of simple calculation, i.e. “do I have the right numbers and cards to break through their defenses” to one of information control and bluffing. The Runner doesn’t know what they’re actually running on until they’re already there and facing the consequences. On top of that, the Runner must spend credits to use their icebreakers and get through the Corp’s defenses. On the other side of the table, the Corp can see the Runner’s rig and knows what they’re capable of. One bad run might set the Runner back far enough that the Corp can then score their agendas off the table, safe in the knowledge that it will be a few turns before the Runner can successfully run again.

A bad run might even outright kill the Runner. One of my favorite bits of design in Android: Netrunner is the fact that the Runner’s hand of cards is also their health bar. Ice that deals net damage and hitmen who deal meat damage force the Runner to discard cards. Some Ice even deals permanent brain damage, reducing the Runner’s maximum hand size. If the Runner is forced to discard from an empty hand, they’re flatlined and the Corp wins. The Corp, then, wants to make the Runner overstep their bounds, spend their credits and cards getting into the wrong server at the wrong time, and maybe just end the game right then and there.

On the other hand, rezzing Ice to make it actually do anything takes credits. More powerful Ice takes more credits, and the Runner knows this. A common Runner tactic is to make a run on one server, fooling the Corp into spending their money, and then running again on the real target now that the Corp can’t afford to rez the big guns. In addition, now that the Ice has been revealed the Runner can see exactly what they need to prepare for next time they run. It’s for these reasons that Corp players will sometimes choose not to rez Ice when the Runner is encountering it, preferring to save the money for other things and keeping their defenses secret until it will hurt the Runner the most.

Then again, this might not be enough. In a stroke of design genius, the Corp’s hand, draw pile, and discard pile are also servers that the Runner can decide to run on. These are known in Netrunner parlance as the central servers: HQ, RnD, and Archives. To put it another way: while the Runner has to worry about faceplanting into defenses or traps they weren’t expecting, the Corp has to worry about the Runner looking through the contents of their hand and deck. If they happen to access agenda cards while doing so, these are stolen and scored by the Runner. By running the corp’s HQ and R&D early on, before the Corp gets a chance to set up their heavier defenses, the Runner can get a view of what’s to come and get an early agenda point lead.

Even later on, it’s important for the Corp to defend these three central servers. If too many turns go by without agendas drawn, the Runner will grab them out of RnD (draw pile). If the Corp is keeping them in their HQ (hand), this leaves them with fewer options and creates a massive point of vulnerability. With four clicks every turn, a Runner can potentially steal four agendas with four runs on an HQ full of agendas. If the corp is forced to ditch some of these agendas into their Archives (discard pile) to create some room and give themselves options, this creates yet another point of access that they must dedicate resources to protecting. This can lead to the strange situation where the Runner wins the game by finding all of the corp’s nefarious plans just lying around in the trash bin.

It’s also important to note that a lot of Ice doesn’t actually block access to its server but simply inflicts effects, such as damage, on the runner while still letting them pass through. This means that an intimidating stack of Ice may gut the Runner’s rig and leave them brain-damaged and broke with private security kicking down the door, but if none of the Ice technically ended the run then they’re still alive and accessing the server’s contents. It might be worth blowing everything on a last Hail Mary run if victory or defeat is close enough. The Runner can’t afford to wait too long to run, since the Corp will have already advanced agendas while the Runner was setting up, but Running unprepared has plenty of its own risks as well. This makes the ability to scout out and evaluate your opponent’s strategy just as important as a good running setup, since you definitely don’t want to blow everything you have just to access a decoy server.

Unlike the original Netrunner, Android: Netrunner introduced the concept of factions. A:NR’s factions are similar to the heroes of Hearthstone: a deck is built around a single Identity card, or ID, which determines the minimum number of cards in the deck, available influence points for including out-of-faction cards, and provides some sort of bonus or rule change. These can range from providing simple discounts when playing certain cards all the way to tying the player’s hand size to the number of credits in their bank. Runner ID’s represent individual hackers and belong to one of three runner factions, while corp ID’s represent divisions or branches of one of the four corporate factions.

Each faction is a different flavor of cyberpunk. On the Runner side, the Anarchs are classic punks who play fast and loose and can flat out destroy the Corp’s stuff, whereas Criminals prefer to accumulate money, develop a network of contacts and favors, and pull off the perfect heist by flat out avoiding security measures. Shapers are the geniuses, savants and artists who run because they can, building big, specialized rigs with exactly the right tool for the right job. On the Corp side, Haas-Bioroid are the manufacturers of self-aware robotic labor; making their clicks efficient, plugging artificial brains directly into the ‘net as their Ice, and dealing permanent brain damage to Runners. On the other hand, Jinteki prefers to use clone labor, and positively welcomes people into their servers. Just remember: Japan has rather lenient laws when it comes to net implant feedback and- oh, dear, that Fetal AI doesn’t like being poked. Gomenasai! Weyland (who’s this Yutani person anyways?) is an old-school megacorporation and enjoys lots of money, throwing money at problems, hitmen, and a complete lack of subtlety. NBN are the new media, and they’re watching you so they can give you exactly the content you need. They’re masters of keeping the Runner tagged and exploiting that fact to accelerate their game while keeping the Runner bogged down.

Since every ID and faction has an associated playstyle, simply seeing your opponent’s ID gives you an idea of what to expect from them. An ID’s influence limit helps change that up. Every faction-specific card is worth a certain number of influence points, and a deck can include out-of-faction cards so long as the total influence cost doesn’t exceed the ID card’s maximum. The big question when building a deck is “how do I use my influence?” Some cards are considered to be universally useful, such as the Shapers’ Clone Chip that allows the Runner to install programs from their discard pile, or the NBN executive Jackson Howard (aka Action Jackson, our lord and savior) who increases Corp card draw and rescues lost agendas from the Archives. A more savvy player will seek to combine the strengths of multiple factions. Possibly the best-known combo is the Weyland-NBN “tag-n-bag”, which uses NBN cards to tag the runner, something Weyland lacks, which then enables the use of Weyland’s pyrotechnic methods of retaliation/urban restructuring normally unavailable to NBN. The core set itself comes out of the box with enough cards to make at least one deck for each runner and corp faction, and there’s more than enough combo potential between factions to make for a good few hours of deck building.

As a side note, it’s important to mention that Android: Netrunner is being distributed using Fantasy Flight’s Living Card Game (LCG) system. What this means is that cards are released in fixed, non-random packs, as opposed to randomized booster packs and decks. There are pros and cons to either system. A:NR has no secondary card market, the ongoing cost of maintaining a competitive card collection is fairly low, and finding a desirable card is a simple matter of buying the corresponding pack. However, it’s important to remember that this means there’s also no secondary card market, and the up-front cost of building one’s initial collection is intimidatingly high. The first two “cycles” of expansion packs are going to rotate out of the tournament card pool this year, but this still leaves a new player facing the prospect of buying at least one, probably two core sets, four deluxe expansion boxes, and 5 or 6 cycles of 6 expansion packs each if they want every single tournament-legal card. This is only important if you want a full collection, though. The core set is a self-contained experience and more than enough to play with a friend. If you’re looking to play with others, chances are that a few questions asked on Reddit or at a local play group will give you suggestions for deck building on a budget. I personally recommend starting with the Creation and Control big-box expansion, and the Blood Money data pack from the recent Flashpoint cycle is full of solid all-round cards. (Paperclip is love. Paperclip is life.)

I’d like to close this unhealthily long ramble by quickly pointing out that Android: Netrunner has some fantastic art direction. Oh, the style is consistent and characterful, the artists are well chosen and the cyberspace art is mind-boggling, but that’s not the best part. The best part is that the card art features very little of what I’d refer to as unnecessary fanservice or “ye gods people STILL think sex sells?!” Not only do we have 14 out of 36 Runner ID’s who are female, and who kick ass in reasonable outfits (Khan is amazing, can we just have a Khan appreciation moment here? Actually, let’s just appreciate all of Matt Zeilinger’s work.), we also have Quetzal, who is doing their own non-binary gene-modded thing. It’s refreshing to play a beautifully illustrated game of any kind where the female characters don’t look like strippers by default. On top of that, there’s some great POC representation, what with an array of races and nationalities across the board and an entire card cycle which takes place across cyberpunk India. It’s great stuff all round, and a sign of hope that game culture can be turned into something more accepting and diverse.

Also, yeah, the cyberspace art is kind of insane.

I’ll admit, at the end of all this obsessive nerdlove, that Android: Netrunner can be difficult to get into. It’s got its own vocabulary and an array of mechanics found nowhere else in the gaming world. I wrote all of the above without going into the details about the rules, and that’s because it’s so very easy to get buried in minutiae. Like Chess, A:NR has a lot of moving parts. Familiarizing yourself with how all the pieces move is just the beginning, because then comes the process of learning when to do what move, and why. On top of this, new pieces are released on a regular basis. This constantly gives everyone new options to learn, but I wouldn’t have it any other way. This is a game like no other that offers nearly unparallelled variety of play and consistently tense and engaging matches. Even with an outmatched deck I’m able to surprise my opponent and keep them on their toes.

But if you like cyberpunk and really engrossing card games, the only advice I can give you is this: grab a friend, split the cost of a core set, get some cool sunglasses, and put on your favorite cyberpunk soundtrack (I recommend the Neotokyo soundtrack, by Ed Harrison or the Frozen Synapse soundtrack, by nervous_testpilot). Array your defenses, pool your funds, and hide the fact you’ve drawn a hand full of agendas. Balance the odds, build your rig, and make one more run.

Tune in next time when Taihus writes something shorter (thank goodness).

-Taihus “tl;dr I like Netrunner a lot and so should you” @raincoastgamer

Android: Netrunner at Fantasy Flight Games

Design Lessons from Poker - Richard Garfield -- ETC Press (a great little article if you’re interested in strategy game design)

#Video Games#Gaming#Card Games#Android Netrunner#Android#Netrunner#Hearthstone#Magic the Gathering#The Oblivian Studios#Oblivian Studios#Oblivian#Raincoastgamer#A Rain-Coast Gamer's Ramblings#Taihus#Review#Reviews

5 notes

·

View notes