#Northern pig-footed bandicoot

Text

†Pig-footed Bandicoots (Chaeropus)

Pig-footed bandicoots were recently considered separate to all other bandicoots. Two similar species are recognized, varying in historical ranges and morphology of dentition and feet. Their fur ranged from uniform grey-brown to russet and fawn tones, helping them camouflage into arid sandy desert and grassland. From 32 to 40cms long, they measured up similarly to a small rabbit.

Chaeropus, uniquely, had feet like tiny hooves. They walked on only two functional toes of the forefeet, and one toe of the hind-foot, the rest being vestigial. They were known to run very fast, with a quick bounding gait. Though reported to eat insects, it’s thought they were largely herbivorous.

The Southern pig-footed bandicoot, C. ecaudatus, occurred through desert shrub-lands in the lower part of South Australia extending into Western Australia. C. yirratji, the Northern pig-footed bandicoot, inhabited grassland and sandy desert in central Australia and WA.

Both species were never prolific according to Indigenous oral tradition. However, they were in serious decline by the 19th century and were extinct less than 150 years after European description. Foxes were not yet established in their ranges, and though some cats were, the cessation of thousands of years traditional burning practices is thought to have been the major contributor to their extinction. Burning provided a patchwork of new growth on which to feed alongside recovered zones of shelter. Introduction of sheep and cattle also changed the landscape dramatically, further decimating crucial food sources of native animals.

#Chaeropus#pig-footed bandicoot#Chaeropodidae#Southern pig-footed bandicoot#Northern pig-footed bandicoot#Chaeropus ecaudatus#Chaeropus yirratji#Peramelemorphia#marsupials#australian animals#australian wildlife#Australidelphia#extinction

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Multiple new cryptic species of bilby, and a case of mistaken identity among bandicoots leading to an accidental introduction:

Even after the catastrophic debacle of introducing non-native cane toads, European rabbits, foxes, dromedary camels, feral cats, and invasive invertebrates, Australian settler institutions are cursed with mistakes which unleash invasive animals even when attempting the well-meaning reintroduction of native species.

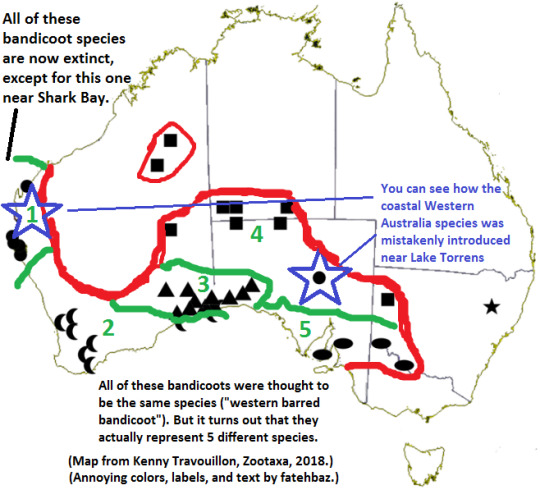

Some new research from 2018 revealed an alarming mistake in ecological management. Basically, you’ve got this cute little bilby from the remote far western coast near Shark Bay which was transported by scientists thousands of kilometers and now has a big strong population just chilling near Adelaide. Bilbies, or bandicoots, are understood to be important to maintaining healthy soils, especially in Mediterranean chaparral zone and the other climatically mild and temperate regions of the coast of southern Australia (ranging between Perth through Adelaide to the Melbourne area, and including Tasmania), so there is popular celebration of the reintroduction of bandicoots to environments which they historically inhabited before European agriculture and invasive species led to local extinction of many bandicoots. The western barred bandicoot (Perameles bougainville) went extinct across almost all of its range and disappeared from native habitats on the mainland after European invasion, but a few populations survived on extremely remote islands off the coast of Shark Bay in on the far western coast of Western Australia. Intending to help rehabilitate native soils and plant communities, Australian settler ecologists then took some bandicoots from Shark Bay islands and “reintroduced” the western barred bandicoot over 3000 kilometers away at the Arid Recovery Reserve, near Lake Torrens area north of Adelaide. This was done because settler scientists thought that this bandicoot species had historically lived across much of southern Australia. Uh oh: It turns out that this western barred bandicoot lineage was historically only native to a small portion of the western coast of Australia near Shark Bay far, far away and was never native to the Adelaide or Lake Torrens area, because what was assumed to be the “western barred bandicoot” was actually 5 different cryptic species. 4 of these species are now extinct. The only living member of this bandicoot lineage remains only at Shark Bay. But now, these Shark Bay bandicoots are living north of Adelaide, where a couple thousand of them live at Arid Recovery Reserve.

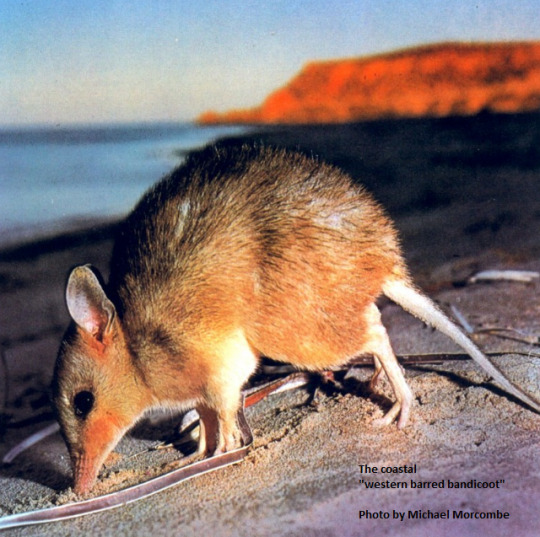

A western barred bandicoot from the coastal Western Australia population at the islands of Bernier and Dorre:

Kenny Travouillon, the lead researcher who reported the cryptic species and new understanding of bandicoot biodiversity, was featured recently in this report from Western Australian Museum, February 2018:

“For example, many people will have seen the Quenda (Isoodon obesulus fusciventer), a bandicoot familiar to Perth backyards. For more than 150 years the Quenda had been thought to be a subspecies of the Southern Brown Bandicoot (Isoodon obesulus) from the east coast of Australia, when in fact our research shows that it is a distinct species and more closely related to the Golden Bandicoot (Isoodon auratus) endemic to WA and found on Barrow Island and throughout the Kimberley.”

“We also re-evaluated the Western Barred Bandicoot (Perameles bougainville), a species now only found on islands near Shark Bay, and we found that it is in fact a complex of five distinct species. Four of these species had been named in the 1800s, but we described a new species from the Nullarbor region, the Butterfly Bandicoot or Nullarbor Barred Bandicoot (Perameles papillon). This is a new species that went extinct between 1920 and 1960, as a result of feral carnivores spreading west,” he said.

Four of the eight bandicoots that once lived in in WA are now extinct: the Pig-footed Bandicoot (Chaeropus ecaudatus), the Desert Bandicoot (Perameles eremiana), the Marl Bandicoot (Perameles myosuros) and the Butterfly Bandicoot (Perameles papillon). The four that remain are the Quenda (Isoodon fusciventer, previously known as the Southern Brown Bandicoot), Northern Brown Bandicoot (Isoodon macrourus), Golden Bandicoot (Isoodon auratus), and the Little Marl (Perameles bougainville), which was previously known as the Western Barred Bandicoot. [End of excerpt.]

Here’s a story on how the confusion has resulted in a non-native bandicoot species being reintroduced where it didn’t belong:

An endangered Australian bandicoot that was reintroduced to the Australian mainland is now believed to be one of five distinct species, and researchers say it may have been a mistake to introduce it to South Australia.

Scientists working for the Western Australian Museum have published research that concludes that what has been known as the western barred bandicoot is in fact five distinct species – four of which had become extinct by the 1940s as a result of agriculture and introduced predators. The species were closely related but occurred in different parts of Australia.

In the 2000s, western barred bandicoots that had survived on the arid Bernier and Dorre islands off Western Australia were reintroduced to the mainland, including to a predator-proof reserve in outback South Australia. But the new study shows the surviving species that was translocated to that part of the country would never have occurred there previously. Lead researcher Dr Kenny Travouillon made the findings after analysing skulls and DNA from tissue from specimens held in collections in Paris and London.He said the research, which was published in Zootaxa, came to the conclusion that the western barred bandicoot was the only remaining species of the five.

The species that has been reintroduced around Australia would have originally occurred only in parts of Western Australia. “On the mainland, that species should have only been in WA along the coast from Shark Bay to Onslow,” he said. “They should never have been brought to South Australia, but that decision was made from the old research.” Dr Kath Tuft, the general manager of the Arid Recovery Reserve in South Australia, said there were now as many as 2,000 western barred bandicoots at the reserve. She said what had been considered a reintroduction of the species was now technically an introduction. [End of excerpt.]

-----

Important distinction: There is another celebrated - and more successful - bandicoot reintroduction project involving a different species.

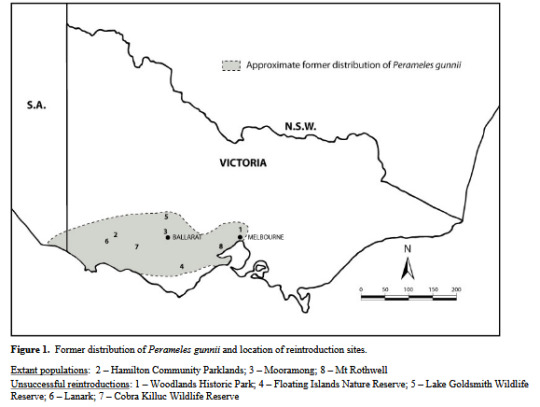

The eastern barred bandicoot (Perameles gunnii) lives on Tasmania and on the mainland in southern Victoria near Melbourne. The population that once inhabited mainland ecosystems almost went entirely extinct, but there are multiple successful reintroduction sites in Victoria and a captive breeding program.

The species also lives on Tasmania, but here are the reintroduction sites on the mainland near Melbourne [map from the species recovery plan, State Government Victoria]:

This bandicoot species does belong in mainland southern Australia.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Extinct Species Graveyard at the Bronx Zoo’s BOO AT THE ZOO Event was fascinating–and sad.

Nathan and I love to visit the Bronx Zoo, which is just about an hour from our house—it’s like being on vacation for a day, and it could be said the zoo is part of our lives (we’ve “financially adopted” many of their animals over the years, everything from a bat to a Madagascar Hissing Cockroach we named Mountain King). Since we’re members, we try to make it down for the zoo’s special events throughout the year.

October brought Boo at the Zoo: weekends full of activities such as a beer garden, pumpkin carving demonstration, not-really hay rides, marshmallow roasting pits, candy trails, a corn maze—and my favorite, a Haunted Forest in the abandoned World of Darkness Building. Little known fact about me? It was my first-ever walk-through Haunted House, and I did pretty well!

It was lots of fun to see kids in costume.

Look who I ran into in New York City!

…and to visit our hissing cockroach, Mountain King.

My Valentine’s Day Gift to Nathan

Check out Mountain King! He is clearly aptly named. Look how large he is compared to the others, and a spectacular gold color (which you can’t really see in this terrible light).

The exhibit that struck me most was the Extinct Species Graveyard, which was set up in a little-used grove of trees next to The Mouse House. It wasn’t there for a Halloween thrill, nor was it there as just another decoration to fill up space; it seemed part educational, and part memorial. I was surprised by the profound sense of sadness I felt as we wandered through the headstones.

Here’s a tour!

The graveyard was located on a perfect, flat, shady — and unused the rest of the year — spot next to The Mouse House.

The area where this was set up made it feel real.

Officially discovered in the late 1600s, the Falkland Islands Wolf’s tame nature spelled its doom—it hadn’t learned to fear humans, so settlers could easily trick it into coming close enough to kill it. They were hunted for meat and fur, and were considered threatening to sheep. The last one was killed in West Falkland in 1876. For a thorough history (that looks to be well-researched—loads of legitimate sources, here), visit http://messybeast.com/extinct/warrah.htm

Passenger Pigeons were abundant in the 19th century, and tales of their titanic flocks—they took over entire forests, appeared thick as waterfalls, and left entire towns blanketed in feces—are just plain hard to believe. They were basically hunted out of extinction, both for their meat by starving frontiersman, and because they were a nuisance: they competed with farm animals for foodstuffs, among other things. Once the railroads came into being, there was no stopping hunters and trappers from sporting these animals right out of existence. The last known Passenger Pigeon’s name was the Cincinnati Zoo’s Martha, and she died in September of 1914. For more information, check out Audubon’s “Why the Passenger Pigeon Went Extinct” here: http://www.audubon.org/magazine/may-june-2014/why-passenger-pigeon-went-extinct

The Tasmanian Tiger was killed off on the Australian mainland by widespread hunting, but survived on Tasmania until the last one died in a zoo in the 1930s. Australians haven’t given up on the hope that this thylacine is still alive, however—to this day, reports of sightings are frequent, and even a recent episode of Expedition Unknown had Josh Gates out hunting for it. Initially, scientists had proposed many theories for the creature’s extinction on Tasmania, although there is new evidence to suggest that it was a changing climate that was the culprit http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/09/28/mystery-disappeared-tasmanian-tiger-finally-solved/.

The story of the last authenticated Labrador Duck’s demise is rather sad http://www.chemunghistory.com/pages/labradorduck.html, but literally, almost nothing is known about this bird—its breeding was done in such remote areas (it’s suspected way up in Greenland) that it died out almost before we noticed. Apparently once prevalent on Long Island Sound, we do know, thanks to a journal called Arctic Zoology in 1785, that a specimen was sent from Connecticut to England (see where I got this from here: https://birdsna.org/Species-Account/bna/species/labduc/introduction). Not very exciting, but there is one ornithologist who made it his mission to visit every single specimen (there are 55) left in existence, which he details in his book The Curse of the Labrador Duck. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/the-curse-of-the-labrador-duck-16641319/

Probably the poster child for extinction, the Dodo Bird has something in common with the Falkland Island Wolf—it had no fear of humans, because it had never had to fear anything before. Although it’s widely held that sailors arriving on the island of Mauritius, near Madagascar, hunted them and ate their eggs, another theory suggests that it was the cats, rats, pigs and other animals the sailors brought with them went feral. Read more in a Forbes Magazine Quora reprint, “What Happened to the Last Dodo Bird?” here. https://www.forbes.com/sites/quora/2016/09/20/what-happened-to-the-last-dodo-bird/#2eb2d48e9c2b

The Pig-footed Bandicoot, an adorable little Australian marsupial, is believed to have not survived the introduction of European cattle, as that would’ve cause a major change to the environment and the availability of food. Although the last verified individual was seen in the early 1900s, there’s photographic, video and audio evidence to suggest the creature may still be alive and well…sounds a little far-fetched to me, but judge for yourself: http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2007/04/pig-footed-bandicoot-rises-dead

Related to today’s manatees and dugongs, Steller’s Sea Cow, indigenous to the northern Pacific, were hunted to extinction in the 1700s by Russian and European fur traders. Another theory floating around out there attributes the final blow for this species to the stress on the sea otter population which caused a rise in sea urchins which caused a depletion of kelp—the Steller’s main foodstuff. More information here: https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2017/04/pleistoseacow/522831/

The Golden Toad lived in Costa Rica’s Monteverde Cloud Forest and was declared officially extinct in 2004. This animal was unique in that males were a dazzling orange, but the females came in many different colors, among them yellow and green. For a long time it was thought that global warming killed these stunning animals, but now they think it might’ve been a fungus: http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2010/03/global-warming-didnt-kill-golden-toad

In another case of “we didn’t realize what we were doing,” the Quagga, which was indigenous to South Africa, died out in the late 1800s. Like many other animals of the plains, they were ruthlessly hunted—they were regarded as competitors for the same food as sheep and goats. What’s come to light is that they were not a separate species of zebra, but a subspecies of the zebra we all know and love. There is a revival project going on in South Africa, which you can read more about here: https://quaggaproject.org/

The Greak Auk—which I’ve seen referred to as “the original penguin”—was scattered all over the northern Atlantic, and was exploited for its eggs, feathers, oil, and fat. Archeological finds also suggest that it was important to ancient maritime peoples. The saddest story, though, is the one of the crew of a ship which tied the bird’s feet together and attempted to take it home. When a violent storm hit, the sailors were certain it was the work of the “devil bird” they’d brought on board, so they stoned it to death. An extensive history in Smithsonian Magazine’s “When the Last of the Great Auks Died, It Was by the Crush of a Fisherman’s Boot,” here: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/with-crush-fisherman-boot-the-last-great-auks-died-180951982/

The Carolina Parakeet’s story is especially tragic, because it was the only species of parrot native to the United States. The last known wild specimen was killed in 1904, and the last captive one died in a zoo in 1918. This bird had a few causes of death: habitat loss, the pet and fashion trades, and farming. There’s a pretty extensive discussion in Audubon’s “The Last Carolina Parakeet” here: http://johnjames.audubon.org/last-carolina-parakeet

I’ve always had an affinity for toads, so here I played around with getting a selfie. Not great.

Me and the toad’s ass. Nathan took this one.

Nathan loves the Tasmanian Tiger. So this is the one he chose to pose with.

The Bronx Zoo’s Extinct Species Graveyard Nathan and I love to visit the Bronx Zoo, which is just about an hour from our house—it’s like being on vacation for a day, and it could be said the zoo is part of our lives (we’ve “financially adopted” many of their animals over the years, everything from a bat to a Madagascar Hissing Cockroach we named Mountain King).

#Boo at the Zoo#Carolina Parakeet#Dodo Bird#extinct species list#Falkland Islands Wolf#Golden Toad#Great Auk#Halloween events in New York City#Labrador Duck#Madagascar Hissing Cockroaches#Passenger Pigeon#Pig-footed Bandicoot#Quagga#Steller’s Sea Cow#Tasmanian Tiger#The Bronx Zoo#where can the kids go to dress up in costumes in New York

1 note

·

View note