#Lyrical themes: Spirituality War Violence Slavery Politics

Audio

Soulfly - Prophecy

#Soulfly#Prophecy#Self titled#Release date: March 30th 2004#Full-length#Genre: Nu-Metal with Tribal influences (early); Groove#Lyrical themes: Spirituality War Violence Slavery Politics#USA

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Childish Gambino’s ‘This Is America’ and the New Shape of Protest Music

youtube

In 2014, a Rolling Stone poll declared Bob Dylan’s "Masters of War" the best protest song of our time. Recorded in April of 1963, during that fierce spell of racial and economic tumult, Dylan, in his folksy pragmatism, rages against the Cold War and the military industrial complex, singing: "You play with my world/ Like it’s your little toy." Corralled by social margins during that same era, the tenor of resistance for artists like Sam Cooke ("A Change Is Gonna Come") and James Brown ("Say It Loud—I’m Black and I’m Proud") was voiced in anthems of anti-racism and self-pride. Out of the 1970 Kent State shootings—where the National Guard killed four students during a school protest—Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young recorded the stringent "Ohio."

Donald Glover’s trap gospel "This Is America" is a piece of trickster art that soundly rebukes the natural DNA of the protest song and constructs it into a freakish chronicle of imprisoned torment. In the dozen or so times I’ve watched the 4-minute video, which was released last Saturday and has already amassed 50 million views on YouTube, I kept thinking how much it reminded me of Kara Walker’s grand Antebellum silhouettes, which juggle themes of the grotesque—torture, death, slavery—in one graceful sweep.

Related Stories

Jason Parham

Dear White People, The Rachel Divide, and the Hard Questions of Identity

Jason Parham

On Dirty Computer Janelle Monáe Breaks Out of Her Android Persona

Jason Parham

Beyoncé, Kendrick, Kanye, and How the World Seeks to Limit Black Genius

Working under his rap pseudonym Childish Gambino, Glover, like Walker, suggests a story of impossible escape. It’s tough work, blood-soaked and vacant redemption, but—and here’s where the artifice begins to reveal traces of brilliance—it’s playful and soul-moving to the point one only wants to keep peering into its dark interiors, waiting for the next truth to sprout.

Hiro Murai, who directed the video, is no stranger to Glover’s rhythms and deceptions, having lensed Atlanta’s wooziest, most disorienting episodes (“Teddy Perkins,” “The Woods”). Here, he seems content to let the scene unfold simply; all the kineticism comes from Gambino, who slinks, then transforms with cartoonish ferocity. With hollow-eyed conviction and no forewarning, he shoots a black man in the head from behind in one sequence, and rifles down a 10-person choir in another. The warehouse tornadoes into chaos and smoke. "This is America," Gambino insists. "Don’t catch you slippin’ up/ Look at how I’m livin’ now/ Police be trippin’ now." The lyrics are unadorned, raw, hauntingly spiritual. Later, over a ribbon of oily vocals, he tells us: "Grandma told me/ Get your money, black man." But the ironies have run flat by then—there are no riches to be had. The jig is up.

Notice, too, how the beat is uptempo, sporadically layered with Afrobeat pulses and church hymns. Gambino and his co-producer Ludwig Goransson trick the ears; they fabricate joy and stack it against Murai’s jamboree of ruin and violence. Atlanta rap contemporaries—among them, Young Thug, Quavo, Slim Jxmmi, and 21 Savage—enter the song’s orbit through a gumbo of yelps, ayes, skrrts, and woos. Both song and video take on the impression of collage.

RCA Records

"This Is America" is successful in the way all art should be: Its meaning wraps around each listener differently, a beautiful, nebulous showpiece with a thousand implications. How Gambino and Murai go about bringing those implications to the surface—turning the suffering and trauma of black people into a cinematic playhouse with no way out—and whether that makes it truly vital, is harder to sift through. (Notice that Gambino’s grim odyssey never takes him beyond the white walls of the warehouse, almost as if he’s trapped.) What "This Is America" ends up becoming is one of the most unconventional protest songs of the modern era.

The images are especially significant to Gambino's puzzle. For most people, "This Is America" was first consumed in video form—the song and footage were released simultaneously during Glover’s Saturday Night Live performance last weekend. The images, above all I believe, are what Gambino wants to resonate, to burn, to damn. The sum is one of naked invention—destruction so bare in its presentation it’s hard to know what exactly the viewer should be looking for.

There are three videos happening within Murai's scope. The first is in the foreground, where Gambino and a cluster of school kids perform choreography sewn together from across the black diaspora, invoking the Gwara Gwara with identical rigor as they do Memphis rapper Blocboy JB’s popular "Shoot" dance (which went viral thanks to a collaboration with Drake). The second video is the background, a canvas of unblinking devastation: burning cars, falling bodies, raging crowds. A world of gun and flame. The third is both of these ecosystems working in symbiotic tandem. Together, they imply complicity on the part of its black actors—that there is plenty of fault to share in the destruction.

'This Is America' diverges from the protest song lineage, insisting instead on pain: working to accept it, to get past it, but never being able to.

That very duality, even if just teased at, is precisely what makes "This Is America" such an unorthodox protest song. Whether imbued with a social or political slant, songs of resistance typically envision a clear villain or threat—a president, a war—but Gambino doesn’t just cough up one, he gives us a multitude. There are no solutions. No paths forward. Just a trove of questions.

After the antiwar soundtrack of the 1960s and ’70s, the protest song pushed forward. Under the boot of Reaganomics, incendiary rap group NWA found a target in law enforcement with 1988’s "Fuck Tha Police," followed by Public Enemy’s rallying call "Fight the Power." Years later, in 2004, Green Day would damn the Bush administration with timeless punk brava. "Well, maybe I’m the faggot, America/ I’m not a part of a redneck agenda/ Now everybody do the propaganda/ And sing along to the age of paranoia," they sang on 2004’s "American Idiot."

With Black Lives Matter (Janelle Monae’s "Hell You Talmbout") and #MeToo (MILCK’s "Quiet") came resounding psalms to the opposition of the day. In 2016, YG and Nipsey Hussle’s "FDT" gave us a plain-spoken mantra—"Fuck Donald Trump"—that has yet to lose bite. Collectively, these were songs meant to check the power-drunk, the intolerant, the warmongering, the racist. Their force lay in their ability to defeat apathy, to anger, even to galvanize.

"This Is America" diverges from this lineage, insisting instead on pain: working to accept it, to get past it, but never being able to.

And in this, his ultimate trick is his most nightmarish. Throughout the video, Gambino and the school children are the lone people untouched, dancing with the history of Jim Crow alive in their feet, contorting and romping, faces plastered with sly, elastic grins. But it turns out to be a mirage—in the final flash, Gambino’s character is seen manically fleeing down a dark hall, a mob at his back. With harrowing clarity one last note boils, then pops: even when you play their game, they still turn on you. "This Is America," unlike so much protest music, ends as it began—with death, pain, blood. We never know what exactly comes of Gambino, but Young Thug’s closing lyrics bear the impact of a dagger. "You just a big dawg, yeah/I kenneled him in the backyard."

More WIRED Culture

What does “self-care” mean amid the barrage of news and social media?

The strange history of one of the Internet’s first viral videos

Believe it or not, our best hope for civil discourse is on …. Reddit

Related Video

Gadgets

How Hip-Hop Producer Steve Lacy Makes Hits With … His Phone

Steve Lacy is a pretty big deal. He's part of the band The Internet, he's a producer for J. Cole and Kendrick Lamar, and he just put out his first solo album which he made on his iPhone.

Read more: https://www.wired.com/story/donald-glover-this-is-america-protest-music/

from Viral News HQ https://ift.tt/2G6gf7P

via Viral News HQ

0 notes

Text

Wailing Souls: Wailing

Jamaica had two realities then: a tropical paradise of sandy beaches, crystal blue seas, and feel-good music; the other, a nation overrun by violent drug posses, permanently scarred by a recent history of CIA intervention and subversion, and a deeper historical legacy of slavery and colonization. The question of which reality would prevail seemed to hang heavy in the air in 1980, as the Wailing Souls recorded their album Wailing—an album shaped by its earthly means and sung to the angelic spheres.

At the turn of the new decade, the post-independence euphoria that had defined Jamaica in the 1960s and the strident self-determination that defined the ’70s gave way to a new era of garrison politics, an unprecedented level of political violence (over 800 people killed in Kingston in the months leading up to the October elections), and the bloody consequences of Jamaica’s increasing role in the regional cocaine trade. The utopian vision of Rastafari—the Afro-Jamaican religion that preached a return to nature and repatriation to the ancestral African homeland—was being rapidly eclipsed by the hard local realities of the country’s position as a regional pawn in the Cold War and the effects of global free trade policies.

The music scene could not help but be affected by these shifts. If the ascension of Bob Marley and the influence of Rastafari on roots reggae were dramatic developments of the 1970s, the next dramatic turning point occurred in 1984 when producers abandoned the recording of live bands altogether, in favor of the stripped-down, pre-programmed rhythms of cheap Casio keyboards. These producers initially attempted to replicate the old reggae dancehall sound, but once the music went digital, it rapidly evolved into a radically different animal. Of course, the mechanization of Jamaican music followed a pattern that was already well underway in the United States and other parts of the world. But for those who had listened to reggae for its spiritual or political qualities or its earthy, organic sensibility, something seemed irretrievably lost.

The pre-digital early 1980s were a period of transition between these two dramatic eras of Jamaican music, an interregnum that symbolically began with the death of Bob Marley in May of 1981. Although many groups of the roots reggae era adapted to the new era and continued to make great music, the new style was largely defined by a younger generation of dancehall deejays with names like Yellowman, Charlie Chaplin, Josey Wales, Eek-A-Mouse, Tiger and others whose “slackness” lyrics of sex, ghetto violence, braggadocio and bling helped set the more aggressive tone of the new decade.

This new form of reggae, generally called “dancehall,” was associated with a number of emerging producers including Sugar Minott, Nkrumah Jah Thomas, Linval Thompson and Thompson’s protégé, Henry “Junjo” Lawes. Lawes in particular was on a hot streak during these years, best-known for the string of hits he produced with Yellowman. His unique sound was partially crafted by using the Roots Radics as his session band. The Radics were built around the rhythm section nucleus of Errol “Flabba” Holt, drummer Lincoln “Style” Scott, and guitarist Eric “Bingy Bunny” Lamont (augmented by a number of keyboardists including Winston Wright and Gladstone Anderson), and their sound was stripped-down and stark. Unlike the older, polyrhythmic roots reggae which had developed out of rock steady, the new rhythms tended to be minimalist in construction—at times martially tight and at other times heavy and lumbering—with Scott’s Syndrums garnishing the music with electronic beeps, buzzes and other quirky, futuristic sounds.

But the unique vibe of Lawes’ productions was also a result of them being mixed by Hopeton “Scientist” Brown, a young protégé of King Tubby, the acknowledged master of dub music. Scientist had initially been a mere apprentice at Tubby’s studio, only infrequently mixing until Thompson and Junjo started to use him on a regular basis. But his skills and reputation grew quickly and by 1980, he was mixing most of Junjo’s tunes and dub versions, compiling them on to the series of sci-fi and video game-themed albums that still form the core of his reputation today: Scientist Rids the World of the Evil Curse of the Vampires, Scientist Wins the World Cup, Heavyweight Dub Champion, Big Showdown, Scientist Meets the Space Invaders and Scientist Encounters Pac-Man. Unlike the warmer, more tropical sound of King Tubby’s dub mixing which had dominated the 1970s, Scientist’s treatment of the Roots Radics’ sounded as if he were suspended in the cold, stark spaces between planets, its emptiness only occasionally animated by the fleeting movements of comets, asteroids, and space debris.

Although dub music developed out of reggae as the latter music’s experimental impulse, the two approaches have generally tended to appeal to different constituencies. Inside of Jamaica, dub was most typically used in the dancehalls as a backdrop for the tale-spinning of the sound system deejays. Outside of Jamaica, it tended to appeal to listeners whose ears had been primed by the spacey soundscapes of psychedelic rock. And producers generally encouraged this bifurcation, placing vocal songs on the A-sides of singles and dub versions on the B-sides. But there were occasions when the idea of the song and the dub mix were not necessarily mutually exclusive, and there is a select group of exalted reggae recordings that unite the sonic experimentation of dub with more traditional conceptions of songcraft. The best-known example of this is probably the Congos’ 1977 album Heart of the Congos, a collection of songs gorgeously performed by the Congos and given an equally gorgeous, dubwise production by Lee “Scratch” Perry at the height of his Black Ark studio.

A lesser-known album in the same category is the Wailing Souls album Wailing. The core of the Wailing Souls is the duo of Winston “Pipe” Matthews and Lloyd “Bread” McDonald, generally augmented by one or two additional vocalists as the occasion demands. Friends of Bob Marley & the Wailers since their early days singing together in Trench Town, they were—along with the Abyssinians, the Gladiators, and Burning Spear—one of a number of roots vocal groups that began to record for Coxsone Dodd at Studio One in the early 1970s. The Wailing Souls brought a poignant, yearning sound associated on one hand with musical traditions of the Jamaican countryside and on the other, with African-American soul outfits like the Impressions and the Temptations, who inspired the formation of scores of Jamaican vocal groups. Many of the latter had perfected their gentle harmonizing singing rock steady—the romantic, soul-inspired Jamaican music that, for two or three intense years, set the stage for roots reggae. But by the early 1970s, they had abandoned the smooth crooning of rock steady for a raw, less affected vocal quality, typified by the rough voices of Pipe, Bob Marley, and Burning Spear’s Winston Rodney.

Like the other groups, the Wailing Souls typically sung themes of Rastafarian devotion alongside philosophically-tinged love songs. They cut two albums for Coxsone before moving on to Channel One studio, where they cut a string of excellent records for the Hoo-Kim brothers. Their career took a major step forward in 1979 when they recorded the celebrated Wild Suspense album for Island Records. By the time they began to record for Junjo in 1980, their experience enabled them to blend the romanticism of rock steady and the mysticism and militancy of roots reggae with the new, minimalist dub sound Scientist was crafting for Junjo’s productions. Teaming up with Junjo and Scientist when both were at the peak of their creativity, Pipe’s voice has arguably never been showcased to better effect, and Wailing was to be one of the most special albums of the Souls’ long career.

In fact, the group was initially reluctant to work with Junjo, wary of the gangster element in the producer’s business, not to mention quality control issues. Junjo was one of the producers that made extensive use of versioning—recycling a rhythm track by overdubbing a succession of deejays on it—but the Souls preferred their music to stand alone so that the messages in their song lyrics remained accessible. Furthermore, while the rhythms that Junjo was cutting with Roots Radics undoubtedly hit hard in the dancehall, they sometimes lacked the inventiveness of the rhythms produced by earlier drum & bass teams like Sly Dunbar and Robbie Shakespeare (with Peter Tosh and Black Uhuru), Carlton & Aston Barrett (with Bob Marley & the Wailers) and “Santa” Davis and Fully Fulwood (with Soul Syndicate). But the Souls’ warm four-part harmonies and Rasta themes (filled out on this album by Garth Dennis and George “Buddy” Haye) brought a sonic and philosophical depth to those rhythms that Junjo’s usual deejays never could.

From Scott’s opening drum roll, the entire album is suffused with a feeling of the otherworldly, with the pensive chorus of Bread, Haye, and Dennis mixed like phantoms behind Pipe’s lead vocals, juxtaposed against the stark, hard rhythms of the Roots Radics and spaced-out by Scientist in a haze of echo and reverberation. The lyrics are generally understated, tending toward the poetic, the oblique, and the evocative. The album’s centerpiece is “Who No Waan Come Cyan Stay” (Who Didn’t Want to Come Can’t Stay), a languid, spacey paean of Rasta repatriation. Anyone doubting the emotional power of dub need only let themselves be transported by Scott’s snare chopping up the soundscape like gunshots, his bass drum kicking up thick clouds of reverberation, and Flabba Holt’s bass ringing out with analog delay like a buoy on the sea while Pipe beckons to non-believers one last time as he departs for a heavenly African Zion:

“Oh give us a home

Where the butterflies roam

and the birds sing so sweet…

Who no waan come cyan stay

You can stay, for I am going

It’s so long, so long

I’ve been warning you

Yet you’re trying hard not to accept my word

But when the master’s calling

You will find yourself stumbling

I’ll be waiting by the wayside

Who no waan come cyan stay

You can stay for I am going…”

The other songs continue in the same vein with wistful melodies of love, mystery, foreboding, and Rastafarian devotion. The opener “Penny I Love You” is poetic and philosophical, with the Souls professing their love into the echo chamber and setting the stage for the rest of the album. “Don’t Be Down Hearted” is a jaunty, spiritual exhortation for the Rasta faithful. “Rudy Say Him Bad” is a plea to the gun-toting “rude boys” of Kingston to heed the advice of their elders and renounce their violent ways, lest they “lay down to stay.” “Face the Devil” is rooted in the Biblical book of Revelation, warning of divine retribution and apocalyptic horrors to come. The album closes with the steady, plaintive “Mr. Big More,” with Pipe and the Souls calling out the wealthy for their greed while bemoaning the plight of suffering masses. In true “showcase album” fashion almost all of the songs here are followed by their dub versions, with the vocals entirely removed and Scientist kicking around in the echo chamber, using reverberation and dropping out parts to explore every nook, cranny, and cavern of the soundscape.

The juxtaposition of the Roots Radics’ dancehall rhythms and the rhapsodic voices of the Wailing Souls seemed to encapsulate Jamaica’s arrival at the crossroads of 1980, a moment when the violent changing of the political guard foreshadowed a new era for the island as a whole. In a tense and uncertain season when the smooth harmonizing of vocal groups was giving way to the raucous chanting of the dancehall deejays, the team of Junjo, Scientist, and the Wailing Souls managed to carve an exalted dub cathedral out of the hard rhythms of early dancehall. Casting the group as voices in the proverbial wilderness, Wailing sings the glories of love, while bemoaning the violence engulfing their society and the world, an angelically-voiced clarion call as society gradually arcs toward the dark side.

__

Michael E. Veal is the author of Dub: Soundscapes and Shattered Songs in Jamaican Reggae (Wesleyan University Press, 2007).

0 notes

Photo

Max Cavalera

#Max Cavalera#soulfly era#soulfly#sepultura#Ex Sepultura#Metal#Genre: Nu-Metal with Tribal influences (early); Groove/Thrash/Death Metal (later)#Lyrical themes: Spirituality War Violence Slavery Politics#Brazil#Usa#Years active: 1997-present#1997

38 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Max Cavalera of Soulfly for ESP Ltd Guitars & Basses, Signature Series,"Max-Axe"

#Max#Max Cavalera#Soulfly#Sepultura#Metal#Genre: Nu-Metal with Tribal influences#Lyrical themes: Spirituality War Violence Slavery Politics#Max-axe#signature#guitar#electric guitar#E S P#ESP#ESP Ltd Guitars & Basses

32 notes

·

View notes

Audio

Soulfly - Ecstasy Of Gold

#Soulfly#Totem#Ecstasy Of Gold#Release date: August 5th 2022#Full-length#Genre:Groove/Thrash/Death Metal#Lyrical themes: Spirituality War Violence Slavery Politics#USA#max cavalera

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

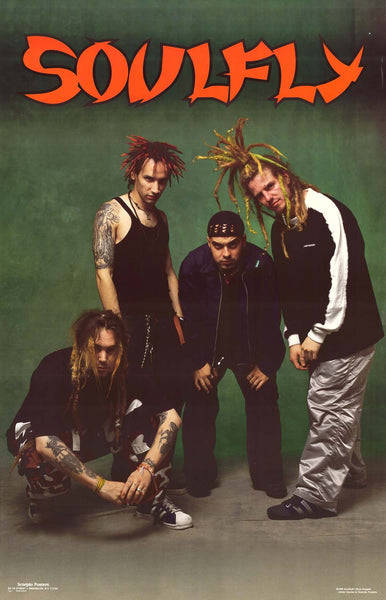

Soulfly

#Soulfly#Genre: Nu-Metal with Tribal influences (early); Groove/Thrash/Death Metal#Lyrical themes: Spirituality War Violence Slavery Politics#USA#1998#90's#90s#Max Cavalera#Max Cavalera (ex sepultura)#Marcello D. Rapp#Roy Mayorga#Logan Mader

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Soulfly

#Soulfly#Genre: Nu-Metal with Tribal influences#Lyrical themes: Spirituality War Violence Slavery Politics#USA#Max Cavalera#Max Cavalera (ex sepultura)#Marcello D. Rapp#Roy Mayorga#Logan Mader

15 notes

·

View notes

Audio

Soulfly - Terrorist (feat. Tom Araya)

#Soulfly#Primitive#Terrorist (feat. Tom Araya)#Release date: September 26th 2000#Full-length#Genre: Nu-Metal with Tribal influences (early); Groove/Thrash/Death Metal#Lyrical themes: Spirituality War Violence Slavery Politics#USA

11 notes

·

View notes

Audio

Soulfly - Corrosion Creeps

#Soulfly#Dark Ages#Corrosion Creeps#Release date: October 4th 2005#Full-length#Genre: Groove/Thrash/Death Metal#Lyrical themes: Spirituality War Violence Slavery Politics#USA#Max Cavalera#Dark ages is certainly my favorite Soulfly album

15 notes

·

View notes

Audio

Soulfly - Cannibal Holocaust

#Soulfly#Savages#Cannibal Holocaust#Release date: September 30th 2013#Full-length#Genre: Groove/Thrash/Death Metal#Lyrical themes: Spirituality War Violence Slavery Politics#USA#Max Cavalera#Post sepultura

10 notes

·

View notes

Audio

Soulfly - Rot In Pain

#Soulfly#Totem#Rot In Pain#Release date: August 5th 2022#Full-length#Genre: Nu-Metal with Tribal influences (early); Groove/Thrash/Death Metal#Lyrical themes: Spirituality War Violence Slavery Politics#USA

4 notes

·

View notes

Audio

Soulfly - Pain

#Soulfly#Primitive#Pain#Release date: September 26th 2000#Full-length#Genre: Nu-Metal with Tribal influences (early); Groove/Thrash/Death Metal#Pain (feat. Grady Avenell & Chino Moreno)#Lyrical themes: Spirituality War Violence Slavery Politics#USA

9 notes

·

View notes

Audio

Soulfly - Jumpdafuckup (feat. Corey Taylor)

#Soulfly#Primitive#Jumpdafuckup (feat. Corey Taylor)#Release date: September 26th 2000#Full-length#Genre: Nu-Metal with Tribal influences (early); Groove/Thrash/Death Metal#Lyrical themes: Spirituality War Violence Slavery Politics#USA

11 notes

·

View notes