#Japanese Art Deco Lacquer and Textiles

Text

Deco Doings - September, 2023

View On WordPress

#1933 Chicago Wold&039;s Fair#Art Deco Society of California#Art Deco Society of Los Angeles#Art Deco Society of New York#Chicago Art Deco Society#Gatsby Summer Afternoon#Golden Age of Hollywood#Japanese Art Deco Lacquer and Textiles#New York Adventure Club#Sunnyside Queens#The Ringling; The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art#Travel in the Jazz Age#Vintage Cars

1 note

·

View note

Text

10 MOST OVERLOOKED WOMEN IN THE HISTORY OF ARCHITECTURE: EILEEN GRAY

Editor’s Note: This article was originally posted in January 2015. Read more about the 10 Most Overlooked Women in the History of Architecture.

In 2013 ArchDaily ran a post on the 10 Most Overlooked Women in Architecture History. This post is the third in a series of mini-tributes to each of these architects. Read the previous post on Marion Mahony Griffin.

Eileen Gray began her career in Paris at the beginning of the Twentieth Century as a designer of Japanese-style lacquered screens, and would eventually become one of Europe’s most influential Modernist designers. While embracing much of the “revolutionary new theories of design,”1 Gray always remained independent and did not align herself with any particular design movement or group.2

Eileen Gray was born in Ireland in 1878; growing up, her artist father encouraged her creative talent. “He also allowed Gray to enroll at the Slade School of Art in London to study painting.”2

Gray soon tired of studies there and headed to Paris where she worked designing lacquered screens in the studio of Sugiwara, a Japanese artisan. She exhibited her screens in Paris and notice of her work earned her interior design commissions. By the early twenties Gray was designing Art Deco furniture and textiles for her clients, the most notable of these projects was “an apartment on Rue de Lota.”2

Gray’s “contribution to the 1923 Salon d’Automne was praised by fellow exhibitors including Le Corbusier and architect Robert Mallet Stevens.”1 It was architecture critic Jean Badovici, however, who became Gray’s mentor and collaborator.3 In 1926 the pair designed House E-1027 in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, France with Gray designing the furniture. She furnished Badovici’s studio as well.2

At the end of the 1920s Gray designed her own home in Tempe à Pailla in southeastern France,3 but by the end of the 1930’s she had withdrawn into “an increasingly reclusive life”2 at her home there. Gray experienced great upheaval in her life and career during World War II. She was forced to leave her beloved home at Tempe à Pailla and lost most of her possessions stored in Saint-Tropez when the Germans bombed the area.3

After the War, Gray lived quietly in Paris, accepting the occasional commission, but dropped out of the mainstream design world. By the middle of the century her work became largely forgotten. In 1968 an article published in Domus Magazine gained new recognition for Gray’s designs.2 In the early 1970s, her last project was for Aram, “a London-based furniture store”2 to reintroduce her iconic furniture designs to market.1 “Gray died in 1976 at the age of 98.”3

Eileen Gray & Jean Badovici, House E-1027 (1926-27), Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, France. Source.

References

Aram, (2011). About the Designer: Eileen Gray. http://www.aram.co.uk/designers/eileen-gray.html#

Design Museum, (n.d.). Profile: Eileen Gray. http://designmuseum.org/designers/eileen-gray#sthash.h5VE5Xso.dpuf

Wikipedia, (2014). Eileen Gray. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eileen_Gray

0 Comments

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

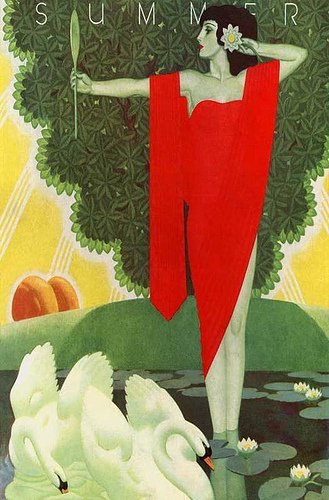

"Sunrise/Sunset" Screen. 1930. Jean Dunand (French (born Switzerland), Lancy 1877–1942 Paris). Lacquered wood, gold. 72" x 240". For centuries, Asian craftsmen had customarily applied coats of natural lacquer as a decorative and protective finish for their objects. In 1912 Dunand, fascinated by examples he had seen, learned the then closely guarded secrets of traditional Asian lacquering from Seizo Sugawara, a Japanese master living in Paris. Combining age-old techniques with contemporary forms and decorative designs, Dunand soon began producing stylish up-to-date furniture and decorative panels while experimenting with new ways of using lacquer, incorporating it into jewelry, textiles, and even society portraiture.

This spectacular screen is a tour-de-force of sumptuous restraint. The glimmering warmth of its monochromatic gold surface, appropriate to the solar imagery, typifies the French Art Deco approach to metallic finishes—luxurious rather than functional. While the rising-sun motif may have been used either in homage to his Japanese teacher or as a subtle reference to the Asian origins of his technique, the abstract simplicity of the composition shows Dunand at his best: elegant, lyrical, and thoroughly modern. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

4 notes

·

View notes