#I usually fall on the 'I'd rather it be easy to design and complex to sew instead of easy to sew and complex to design' side of the scale

Text

Idk what I want to work on next besides probably another giant octopus and a Bucky Bear for my MTH auction fill, so I'm taking suggestions! What do you think I should make next?

#the person behind the yarn#as usual I make no promises or guarantees about what I will make#I never know what spark of imagination will ignite#and suddenly pivot my focus to be lasered in on making a giant octopus for like an entire day#could not have predicted that one lol#also I found someone else's large octopus plushie and their pattern looks significantly easier to design#way more complex to sew!#but simpler to design#I usually fall on the 'I'd rather it be easy to design and complex to sew instead of easy to sew and complex to design' side of the scale#so idk why the octopus was such an exception for me?#but it really is! it's surprisingly extremely easy to sew#I mean. like. a lotta curves to sew#but if you pull a bit on the fabric as you sew the tentacles you just get tentacles that are twisting a little#which is fine because they are tentacles. if anything it's a bonus and makes them look better

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

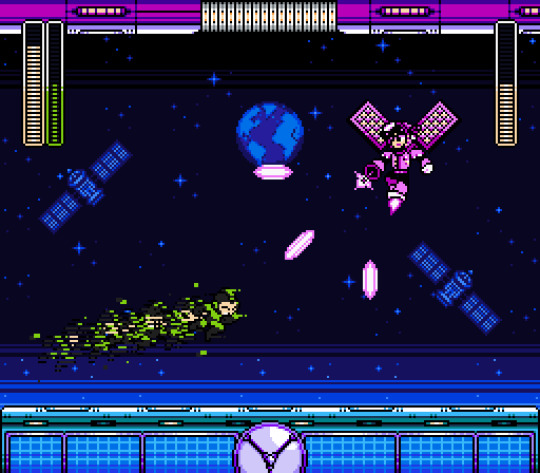

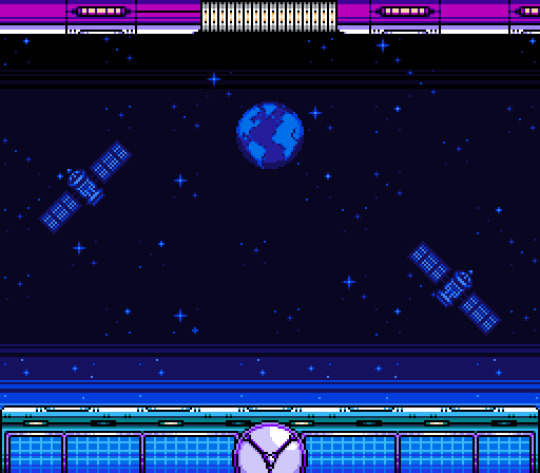

Longtime followers of mine may have seen my faux Mega Man Ultimate screenshots, which range from exemplary stage designs to full-on boss battles! However, it's been a little while since I've made another sprite piece of what certain in-game moments of Mega Man Ultimate would look like, and for my next screenshot, I knew just what I wanted to sprite!

My last faux screenshot detailed the electrifying battle against SLN-001, Zap Man, and seeing how easy it was to sprite full screens with the magic of tilesetting, I aimed to make a mockup of a battle against another one of the Synth Legion Numbers, Satellite Woman! And unlike Zap Man's simpler NES-esque boss arena...

... the boss arena of SLN-003 has a lot more going on!

Who doesn't love space? When it came time for me to decide which of the eight Synth Legion numbers to devote my next boss battle mockup to, Satellite Woman was my first choice, because that meant I got to sprite an out of this world background for her by way of tilesetting!

And there was a lot I could do with it, too. While I initially didn't have a whole lot of ideas as to what Satellite Woman's boss arena could look like, I did eventually come up with two goals: for it to have a Mega Man V feel to it as well as referencing her bio, which mentions her base of operations being exactly one hundred parsecs away from Earth.

This is what I came up with! One of the earliest design decisions I made was that I wanted to have Mega Man fall into the boss arena rather than walk into it— we haven't had a lot of robot master boss arenas of a vertical caliber since the original Mega Man! Fortress bosses have entrances of this type, so why can't more robot masters?

Secondly, the arena lacks walls, because I find that the quarters in which you do battle with Satellite Woman feel a lot more vast without them than they would with the usual boss-in-the-box formula. I first planned on having the satellite platform be shorter in width, where if you fell off, it'd be a one-hit KO, but I felt like that wouldn't be too fair (Even if Cloud Man did it first).

Perhaps the most appealing part about the entire background are the drifting satellites and the gorgeous view of Earth— both of which took me quite some time to sprite! The Earth sprite in particular (Which I think was the asset that took me the longest to sprite) fits snugly into a 32x32 tile, whereas the satellites make up a 48x48 tile.

The last design choice I'd like to mention are the colors in this piece. For Satellite Woman's boss arena, I wanted to stray away from the usual NES limitations and go for something a little more flashy— hence my decision to make the space background all kinds of blue hues instead of a solid black (Plus, if I went with the latter, you wouldn't be able to make out Satellite's complex sprites very well!).

I kept switching between purple and light green for the bottom platform, and when I couldn't reach a consensus, I tried a turquoise color to see what that would look like, and it made for a stellar in-between! It was always a given for the space station up above to be colored after Satellite Woman, so I didn't have a lot of trouble figuring out colors there.

And finally, as I've started to do for my art posts, this was the process I went about in designing the arena! Starting with a conceptual sketch of the room I drew in MS Paint, it follows up with a general layout made up of placeholder green and purple tiles, and from there you can see the final product start to form!

With design specifics out of the way, we can touch base on what it's like to be pitted against the connoisseur of the cosmos, Satellite Woman! Her battle takes a lot of inspiration from Star Man's battle from Mega Man 5, with the emphasis on the robot master constantly being shielded and zero-gravity jumping aplenty.

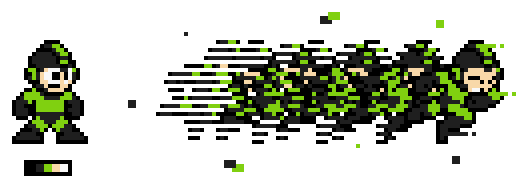

When she's not putting her Reflect Satellite to good use, Mega Man may attempt to land a blow on her... if she doesn't land a blow on him first! The only time you can do damage to Satellite Woman is when her shields are down or when she's firing lasers from her Satellite Buster (Pictured above), so it's very much easier said than done...

That is, of course, unless you arrive with her weakness weapon in tow!

Enter Glitch Strike, the weapon you acquire after defeating the bug-tastic Glitch Man! Glitch Strike allows Mega Man to speedily glitch a lengthy distance in any direction, passing through any projectiles without harm and— with precise aim— may ram into opponents. However, this ability comes with a hefty energy cost (Much like Tornado Blow in Mega Man 9), and you'll only see four or five uses of it with a full meter. Better use them wisely!

Well, that's about everything— this ended up being one of my biggest sprite pieces in a while, and it took a whole lot of thought and experimentation to look just right! I hope you've enjoyed reading through the design process, and more importantly the fruits of my labor!

#Mega Man Ultimate#Rockman U: The Renegades Rise#Mega Man#Rockman#Satellite Woman#Sprite Art#Concept Art#Deep Dives with Star#Coolness#NOW T H I S IS A GALAXY FANTASY. Take notes Galaxy Man!#If you look E X T R E M E L Y closely at Mega Man's sprite in the last image... you'll notice it's a bit different!#I made some alterations to his pose and helmet so it's more of a stylized take of the usual stiffly posed Mega Man sprite#Speaking of poses... Mega Man's Glitch Strike pose took me a while.#I actually referenced another sprite of Mega Man in a similar action-y pose but put my own spin on it so it'd stand out#Spriting his buggy after-images was quite a bit of fun though!#Fun Facts with Star: One big inspiration for Satellite Woman's arena background is a personal favorite background of mine...#Mega Man 10's Wily Capsule background!#You can see Satellite Woman's whole arena takes several cues from it too— from the Earth presence to the lack of walls

33 notes

·

View notes

Note

I had a thought earlier and thought I'd shoot you an ask about it: Do you have any tips on getting better at world-building (I think you're great at it btw)? Also, have you always liked world-building, in itself? I find myself often using worlds other people create, because I'm not very good at creating/thinking of my own, and was wondering if that was lazy of me? Just was wondering what your opinion was, on all that! Just food for thought. c:

Thank you! I’m glad you think I’m good at it!

World-building is a very interesting subject, but it took me a while to even really appreciate what it was. I’ve also spent a lot of time in other people’s worlds and environments, that’s pretty common among fanfiction writers, but I wouldn’t consider it lazy. Not unless you think any fiction set in our world is also lazy. There will always be parts of a story that some people are better at or prefer to focus on, or still need to build up their skills at. It’s normal.

I think a few things are very key to good world-building, though. Or at least in my experience, it’s the stuff I’ve figured out that’s helped me the most.

1. Nothing is original. You might not be entirely sure of where an idea has come to you from, but at the end of the day, there are only so many facets to human existence out there. Our imaginations only carry us so far, and our ideas come from the people around us, and also from their ideas. Artists draw from the things they see and experience, and use references to make stuff more realistic. So do writers. Do not worry that your stuff is unoriginal. Doing your best to abandon that fear is one of the biggest favours you can do for yourself as a writer; there’s a difference between similar concepts and ideas, and plagiarism, and only plagiarism is really a problem.

2. Nothing is without real-world context. This is related to the above. The things you make are coming from somewhere, and that means that they will have implications and real-world parallels. It pays to stop and consider where you’re getting your ideas, and what those ideas are implying about the world around you, too. In order to write stories, you have to be willing to take the stuff of your daydreams, and hammer it out into a narrative. It’s like turning a hunk of rock into a gemstone. You have to cut pieces out, decide what to reshape, what to keep, and what to throw away. If you can’t attack your own presumptions about the real world, you’ll have a harder time shaping a consistent fictional one. But also, at the end of the day, a rough diamond and a faceted one are both still diamonds. People will often be able to tell where you’re pulling your ideas from, so what you say about certain subjects can still have an impact on real-world concepts, and on your readers.

3. Let your setting be bigger than you. When writing, it’s extremely easy to get caught up in your own ideals and frames of reference, and that can mean that you design a world that acts more like how you think it should, rather than how it would. Worlds are big, and to some extent you can mitigate this by being aware that there is more going on than what you’re describing - that your story’s perspective is limited to the characters and events in it, and that contradictory things or mysterious unknowns still linger in the wider scheme of the setting. Your characters shouldn’t know everything that you, the author, knows, and you, the author, shouldn’t know everything about the world, either. An exhaustive list of details can even work against you, because it makes it trickier to keep track of what all your characters do and don’t know as well.

4. Big events are great, but cause and effect is better. When you look at history, you can see the way certain figures and events impacted one another, and connected together to get people to their ends or beginnings. A common mistake in world building is to take the big events - wars, coronations, the fall of empires, the rise of them, etc, etc - and just throw them into the setting without much thought for how they all interact with one another. But it’s like… if you have a nation that’s got a standing army, that’s expensive. Most nations have very small armies of professional soldiers, and instead tend to temporarily conscript people to bulk up their armies in times of crisis, because someone who is busy training and fighting isn’t doing other vital work, like raising livestock or farming crops or building homes, making babies, running households, etc, etc. But they still need to be fed and clothed and offered some kind of shelter from the elements, provided with equipment and a certain degree of entertainment, and things like that. Professional soldiers can spend their time focusing on being the best fighters they can be, so there’s an advantage to it, but you also need to justify having them around, especially if the rest of your country is having to work overtime to keep them fed. So a nation with a big standing army is going to be a nation that finds a lot of reasons to go to war - war lets you bring home spoils, lets you raid someone else’s farms to feed your soldiers, and expand your territory, and tax or enslave conquered peoples, and so on and so forth. You can start your world-building at the point of ‘I want this nation to have a big army’, or you can start it at the point of ‘I want this nation to be war-like’, or somewhere else on the chain of events - but certain things will also imply certain other things. It’s best to be aware of what those elements are when you’re laying out your setting. If you make a nation with a big army that is ‘peaceful’, you either need to explain how that works, or else people will probably think that the reputation is inaccurate (and that’s fine, too, as along as you’re willing to create a nation with one hell of a propaganda machine instead). But if you have a warlike nation, then there will also be other nations that have taken the brunt of its actions and conquests. So you will do better to let a few key traits expand into their implications, than to try and railroad everything into a framework that doesn’t flow naturally from those things. Because if you have your big nation with its standing army and militant inclinations, every other part of the world is probably going to be impacted by its quest for expansion, and if they aren’t, you need to be thinking about why, or else the pieces of your setting won’t fit together very well.

5. Avoid the Golden Mean Fallacy. The Golden Mean Fallacy, also known as the ‘argument to moderation’, is the idea that the perfect solution to any problem lies in compromise. But thereare some situations where saying ‘both sides are in the wrong’ requires a lotof false equivalents or narrative contrivances, even though people often tend to think that this is the most reasonable or neutral stance to take as the sort of arbitrator of the setting. Approaching societal conflicts in your world-building withthe idea that compromise is an ideal solution can actually be really offensive, though, and less ‘neutral’ than beneficial to aggressive qualities in the setting.For example, if one group is trying to commit genocide against another, looking at it and going ‘okay you guys want to live, but these other guys want to killyou, so I think the solution here is to just let them eradicate your culture –that’s really what they’re objecting to, anyway, and then you get to live andthey still get to destroy you, everybody wins!’ is not something you want to present as a fair solution. Sometimes people are just plainly in the wrong. That said…

6. Nevermake any culture/race/ethnicity/etc ‘evil’ in your stories. Doesn’t matter ifit’s orcs, robots, aliens, faeries, or what-have-you. The ‘savage tribe ofmonster people’ or Always Chaotic Evil Race™ is a bad trope and it needs to godie in a fire. If you want an ‘evil group’, you will do far better to alignpeople based on something like ideology or political corruption than race, geography, or traits theyare born with. There are other tropes along these lines that should be avoided, too, in fact there are more of them than I could successfully list in a timely fashion. As a general rule, though, if taking your world-building principles and applying them to real-life groups would result in an appalling statement, you should either change it, or else work it in as a form of propaganda and prejudice which you’re well aware of. That’s the difference between something like ‘mages are the most dangerous people in Thedas’ versus ‘the Templars believe that mages are the most dangerous people in Thedas’. One is you, the writer, making a blanket statement that some groups of people are just born dangerous, whereas the other is you, the writer, creating a scenario where prejudice exists in the setting.

7. Taking something out is often harder than adding something in. For example, building a setting without something like sexism or racism is usually much more complex than building a setting with something like magic or dragons or something. Fantastical elements are flexible, and you can shift the rules of them around to suit your needs without too many people crying foul. Whereas something like sexism is built into a lot of aspects of our society, and sinks into things that many people don’t even think twice about. Trying to create a fictional world where there is no sexism or history of it is, therefore, very hard, because you have to learn as much as you can about the ways in which this prejudice impacts our society and our presumptions, and then try and extrapolate how that would change everyone’s behaviour in a different world. And what you don’t change will immediately tilt your setting towards being the kind of place where biased presumptions are true facts of nature, rather than being a place where bad attitudes merely exist among the people and cultures there. This applies to basically everything, by the way, although it’s usually the most glaring when someone decides that they don’t want to deal with X kind of bigotry, and think that just going ‘it doesn’t exist in this world’ is the simple way out. (It’s not, the simple way out is to go ‘it exists in this world just the same way it does in ours, but I’m not focusing on it’.)

8. Keeping track of things is more important than knowing them off the bat. Everybody knows you’re making stuff up. That’s what they came to this party for. Inconsistencies can happen, but it’s also entirely possible to get so caught up in the planning stage that you never actually do any writing. So a good compromise between spontaneous invention and consistency is to just note the things you add in when you add them in, and then figure out how they might impact the other elements in your story, and set aside potential consequences in case they’re interesting or useful later on. Editing is your friend, and ‘I don’t know, let’s think about it until I do’ is also a vital element to incorporate into your thinking.

9. Be aware that you can mess up, and probably will. In order for any story to be inclusive of a wide enough range of people and cultures to make a whole world, it’s going to require you stepping outside of your own experience, or incorporating stuff that you have only a limited amount of knowledge on. You may very well fuck this up. This doesn’t mean the attempt was doomed, and it doesn’t mean you’re bad at world-building, and it also doesn’t mean that you have to defend your mistake in order to keep your setting from being deemed a worthless heap of junk. Your honour doesn’t ride upon whether or not you can make a convincing argument as to why your intentions outweigh the unintended implications of your actions. If someone points out a mistake, you should think about the ways you can go about handling it and/or fixing it. Maybe you just suddenly made your virtuous heroic group a lot more shady than you thought. Maybe you have to abandon a plot twist you were originally angling for. Maybe you have to make your narrator a lot more unreliable than you initially planned. There are solutions, and most importantly, you gotta listen to the people in the real world whose cultures or traits you borrowed from for your story. Just like when you borrow anything. If it’s not yours, you need to respect that and be mindful of how you use it.

10. Have fun. When you make a new world, there should be things in it that you love. That speak to your delight and sense of wonder. These are the things that often help the most when you’re deciding what to actually make in your world. You want unicorns? Put in unicorns. You want talking dragons? Put in talking dragons. Just think about how they would work, and how people would react to them, and how having them around might change the way the world operates. A lot of stuff will build naturally out of that.

I hope some of this helps!

46 notes

·

View notes