#Governor Herbert Lehman

Text

Alphonse Brengard. Justice delayed, but not denied.

When New York cop-killer Alphonse Brengard walked his last mile at Sing Sing on September 6, 1934 it may have been with a firm sense of time and his crimes having finally caught up with him. Brengard died for a murder effectively committed years before, but he was not to wait in Sing Sing’s infamous ‘Death House’ for very long. After evading the law for several years after the shooting, Brengard…

View On WordPress

#Alphonse Brengard#Anna Antonio#appeal#capital punishment#clemency#death penalty#Eva Coo#Governor Herbert Lehman#Iron Mike Malloy#Judd Gray#Leonard Scarnici#Mad Dog Coll#Nassau County#New Jersey#New Jersey State Prison#New York#Patrolman John Kennedy#Robert Greene Elliott#Ruth Snyder#Sing Sing#State Electrician#Trenton#true crime

0 notes

Text

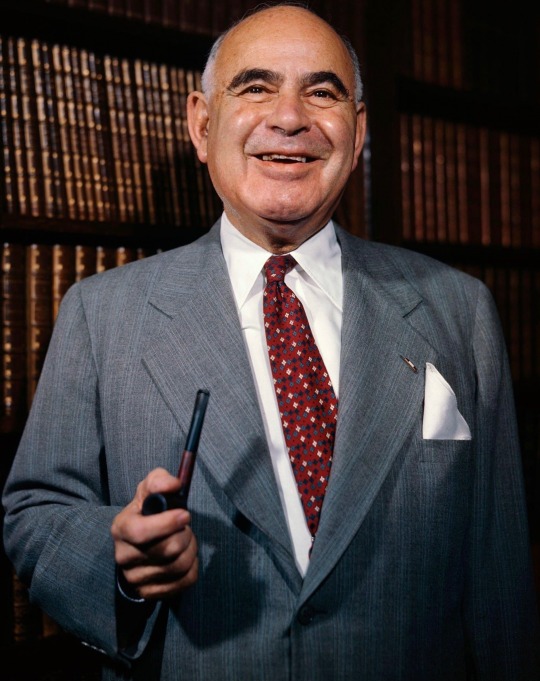

Herbert H. Lehman

#suitdaddy#suiteddaddy#suit and tie#suited daddy#daddy#men in suits#suited#suitfetish#suited men#suited grandpa#suitedman#suit daddy#suited man#buisness suit#suitedmen#americans#democrats#governor of new york#Herbert H. Lehman#Herbert Lehman

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

King George VI and Queen Elizabeth travel in a motorcade during their visit to New York. With them are New York Mayor Fiorello La Guardia and Governor Herbert H. Lehman // June 10, 1939

For reasons of safety and speed, the Royal procession bypassed Broadway and instead took a more ‘open’ route on the way to the World’s Fair in Flushing Meadows:

They seemed to know a great deal about the layout of the city, and they asked many questions about it. I don’t know whether it is just my own disappointment about not being able to take them up Fifth Avenue and Broadway, but I gathered that they would have preferred that route. As we drove up the West Side Highway both the King and Queen asked several times how far we were from Broadway, and how far from Fifth Avenue. They were very much interested in Broadway.

At one point in Queens there was a section that did not seem to be covered well, and a large crowd of people surged downhill to fill it up. One of our motorcycle policemen swung over to keep them in bounds, and the King remarked, as if voicing his thoughts:

‘Don’t worry - the crowd always takes care of itself.’

Fiorello La Guardia // quoted in Voyage of State by G. Gordon Young (1939)

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

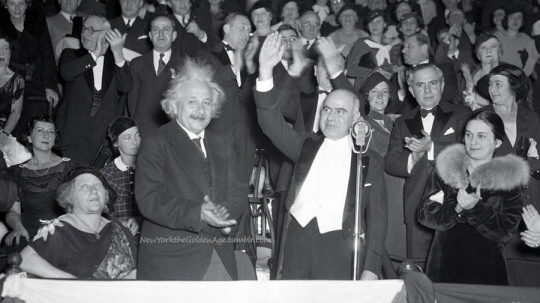

Albert Einstein at the Chanukah Festival, December 23, 1933. Governor Herbert H. Lehman, right, introduces Professor Einstein to the guests gathered at Madison Square Garden to celebrate the Chanukah Festival. Professor Einstein said, "I earnestly hope the Maccabean Festival will be a beautiful demonstration of Jewish solidarity in these critical times."

Photo: New York Sun/Getty Images/Newslea

#New York#NYC#vintage New York#1930s#Chanukah#Hannukah#Albert Einstein#Herbert Lehman#Dec. 23#Chanukah Festival#Madison Square Garden#Jewish solidarity#Festival of Lights#Hannukah Festival#December 23

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

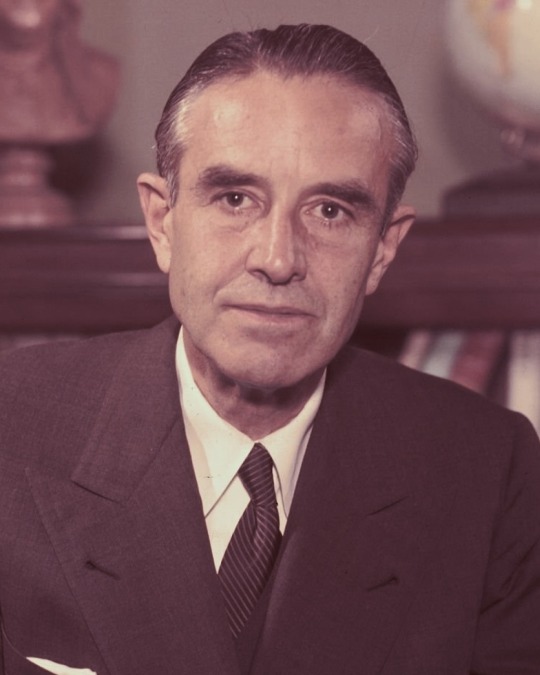

New York Governor DILFs

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Nelson Rockefeller, W. Averell Harriman, Charles Poletti, David Paterson, Mario Cuomo, George Pataki, Herbert H. Lehman, Eliot Spitzer, Malcolm Wilson, Hugh Carey

#Franklin Delano Roosevelt#Nelson Rockefeller#W. Averell Harriman#Charles Poletti#David Paterson#Mario Cuomo#George Pataki#Herbert H. Lehman#Eliot Spitzer#Malcolm Wilson#Hugh Carey#GovernorDILFs

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Milton Carver Davis (born March 29, 1949) is a lawyer who researched and advocated for the pardon of Clarence Norris, the last surviving Scottsboro Boy.

He graduated from Tuskegee University and received his JD from the University of Iowa College of Law. He was an American Political Science Foundation Graduate Fellow, a Ford Foundation Graduate Fellow, and a Herbert Lehman Foundation International Scholar.

He gained international acclaim when as the Assistant Attorney General for Alabama he partnered with Donald Watkins to research and advocate for a full pardon of Clarence Norris, the last known surviving Scottsboro Boy based on innocence. Governor George Wallace granted the parole in 1976 as the first time in the state’s history that a pardon had been granted based upon innocence.

He was the 29th General President of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity. He created the Fraternity’s World Policy Council as a think tank to expand the organization’s involvement in politics and social and current policy to encompass important global and world issues. The World Policy Council has published white papers on the Politics of Nigeria, the War on Terrorism, Hurricane Katrina, the Millennium Challenge Account, and Extraordinary Rendition. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence #alphaphialpha #sigmapiphi

0 notes

Text

This Day In Jewish History

1936: In Atlanta, GA, social worker Arlene (Fox) Uhry and “furniture designer and artist” Ralph K. Uhry gave birth to Brown University alum Alfred Fox Uhry, who “received an Academy Award, two Tony Awards and the 1988 Pulitzer Prize for dramatic writing for Driving Miss Daisy.”

1937: Birthdate of British attorney and businessman Stephen Rubin. The founder of Pentland, he struck it rich with Reebok and Adidas.

1937: The Palestine Post reported that a large police unit accompanied by a detachment of Transjordanian Frontier Force, scoured Galilee in pursuit of Arab terrorists that had murdered two Arab policemen and apparently sought to escape to Syria. In London, Major C.S. Jarvis, the former British governor of Sinai, said that after he had seen what the Jewish settlers had done in various arid areas of Palestine, he would strongly recommend a large Jewish settlement of the entire Negev, which ought to be included in the Jewish state in any partition negotiations.

1937: The Palestine Post reported that the total official population of Palestine was given at the end of September 1937 as 811,347 Moslems, 389,504 Jews, 108,433 Christians and 11,588 others.

1938: The German government decrees that all Jewish industries, shops, and businesses must be forcibly "Aryanized."

1938: At the Ambassador Theatre, the curtain came down on “You Can't Take It with You” a comedic play in three acts by George S. Kaufman and Moss Hart that won the 1937 Pulitzer Prize for Drama after 838 performances.

1939: In Brooklyn, “Jack and Sylvia Israel” gave birth to Leonore Carol Israel who gained fame as forger Lee Israel.

1939: Among the patents issued this week was one issued to Rudoph Feige of Tel Aviv for “a tropical hat with a crown separated from the brim to provide and air circulating slot around the hat…”

1940: Heads of educational institutions and other prominent persons were among the 3,000 attending a funeral service for Rabbi Bernard (Dov) Revel, one of the founders of Yeshiva College which became Yeshiva University.

1940: Debut of Bugs Bunny with the voice supplied by Mel Blanc. Bugs Bunny was not Jewish but Mel was.

1941: Amidst the misery of the Lodz Ghetto, a newly arrived Viennese Pianist, Leopold Birkenfeld held a concert for his fellow Jews. He played Shubert, Liszt and Beethoven brilliantly.

1942(24th of Kislev, 5703): In the evening, kindle the first Chanukah candle.

1942(24th of Kislev, 5703): The Nazis shot three young girls who had escaped from Poznan labor camp

1942(24th of Kislev, 5703): One thousand Jews from Plonsk, Poland, are killed at Auschwitz.

1942(24th of Kislev, 5703): Salomon Malkes, an official of the Lódz Ghetto, commits suicide after becoming despondent over the deportation of his mother.

1942: Herbert Henry Lehman completed his service as the 45thGovernor of New York.

1942: An unknown photographer took a picture of Jews in the Drancy assembly and detention camp which was the departure point for sending French Jews to Auschwitz. The picture is part of the Yad Vashem Photo Archives.

1943: At a meeting with the German ambassador Francisco Franco said, “’Thank God a clear appreciation of dangers caused by Jews led our catholic Kings to insure ‘we have for centuries been relieved of that nauseating burden.’” Oddly enough, Franco actually protected that ‘nauseating burden’ from the clutches of the Final Solution.

1943: Popular American singer Dinah Shore (Frances Rose Shore) the graduate of Vanderbilt University where she was a member of AEPhi, the Jewish sorority, married her first husband today.

1944: Hungarian death march of Jews ends

1944: Beginning of the Greek Civil War in which pro-Soviet Communist forces attempt to destroy the pro-Western government.

1945: Abdul Azzam Bey, Arab League secretary general, announces that member states will boycott all Jewish-produced goods from Palestine beginning January 1, 1946.

1946: Today “The Joint Committee of Jewish Organizations, whose membership includes representatives of nine groups, praised the adoption of clauses by the Council of Foreign Ministers insuring restoration of rights and restitution of property to Jews in Hungary and Rumania in the proposed peace treaties.”

1947(20th of Kislev, 5708): While Jewish workers were evacuating undamaged goods from the Centre a group of Arabs attacked them, killing Yitzhak Penzo,

1947: Broadway Premiere of “A Streetcar Named Desire” which would be revived in London in 1974 with Claire Bloom playing “Blanche DuBois” – a portrayal that led the play’s author to state “I declare myself absolutely wild about Claire Bloom.”

1947: Arab violence continues with an attack on a synagogue in the Old City. Following threats by Arab gangs to burn their dwellings, “Eight Jews living in a house in the Musrara Quarter outside the Damascus Gate were forced to leave their homes”

A lot more: Here

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Union Square, Manhattan (No. 3)

Tammany Hall, also known as the Society of St. Tammany, the Sons of St. Tammany, or the Columbian Order, was a New York City political organization founded in 1786 and incorporated on May 12, 1789, as the Tammany Society. It was the main local political machine of the Democratic Party, and played a major role in controlling New York City and New York State politics and helping immigrants, most notably the Irish, rise in American politics from the 1790s to the 1960s. It typically controlled Democratic Party nominations and political patronage in Manhattan after the mayoral victory of Fernando Wood in 1854, and used its patronage resources to build a loyal, well-rewarded core of district and precinct leaders; after 1850 the great majority were Irish Catholics.The Tammany Society emerged as the center for Democratic-Republican Party politics in the city in the early 19th century. After 1854, the Society expanded its political control even further by earning the loyalty of the city's rapidly expanding immigrant community, which functioned as its base of political capital. The business community appreciated its readiness, at moderate cost, to cut through regulatory and legislative mazes to facilitate rapid economic growth. The Tammany Hall ward boss or ward heeler, as wards were the city's smallest political units from 1786 to 1938, served as the local vote gatherer and provider of patronage. By 1872 Tammany had an Irish Catholic "boss", and in 1928 a Tammany hero, New York Governor Al Smith, won the Democratic presidential nomination. However, Tammany Hall also served as an engine for graft and political corruption, perhaps most infamously under William M. "Boss" Tweed in the mid-19th century. By the 1880s, Tammany was building local clubs that appealed to social activists from the ethnic middle class. In quiet times the machine had the advantage of a core of solid supporters and usually exercised control of politics and policymaking in Manhattan; it also played a major role in the state legislature in Albany.Charles Murphy was the quiet but highly effective boss of Tammany from 1902 to 1924. "Big Tim" Sullivan was the Tammany leader in the Bowery, and machine's spokesman in the state legislature. In the early twentieth century Murphy and Sullivan promoted Tammany as a reformed agency dedicated to the interests of the working class. The new image deflected attacks and built up a following among the emerging ethnic middle class. In the process Robert F. Wagner became a powerful United States Senator, and Al Smith served four terms as governor and was the Democratic presidential nominee in 1928. Tammany Hall's influence waned from 1930 to 1945 when it engaged in a losing battle with Franklin D. Roosevelt, the state's governor (1929–1932) and later U.S. President (1933–1945). In 1932, Mayor Jimmy Walker was forced from office when his bribery was exposed. Roosevelt stripped Tammany of federal patronage. Republican Fiorello La Guardia was elected mayor on a Fusion ticket and became the first anti-Tammany mayor to be re-elected. A brief resurgence in Tammany power in the 1950s under the leadership of Carmine DeSapio was met with Democratic Party opposition led by Eleanor Roosevelt, Herbert Lehman, and the New York Committee for Democratic Voters. By the mid-1960s Tammany Hall ceased to exist.

In 1927 the building on 14th Street was sold, to make way for the new tower being added to the Consolidated Edison Building. The Society's new building at 44 Union Square, a few blocks north at the corner with East 17th Street, was finished and occupied by 1929. When Tammany started to lose its political influence, and its all-important access to graft, it could no longer afford to maintain the 17th Street building, and in 1943 it was bought by a local affiliate of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union. Tammany left, and its leaders moved to the National Democratic Club on Madison Avenue at East 37th Street, and the Society's collection of memorabilia went into a warehouse in the Bronx. The building at 44 Union Square housed the New York Film Academy and the Union Square Theatre, and retail stores at street level, until a complete renovation of the building began in January 2016. The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission designated it in October 2013. Plans to add a glass dome to the building were nixed by the Landmarks Commission in 2014; however, the interior is still slated to be completely rebuilt, including demolishing the theater. In 2015, a scaled-back version of the glass dome was approved by the commission.

Source: Wikipedia

#Everett Building#Century Building#Union Square#New York City#vacation#travel#USA#summer 2019#original photography#cityscape#landmark#tourist attraction#Tammany Hall Building#44 Union Square#lamp#lantern#Mftr’s of Civilian and Military Coat Fronts#ghost sign#glass dome#construction workers#Consolidated Edison Building#skyline#roof#window

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

King George VI, Sara D. Roosevelt, New York State Governor Herbert Lehman, and Elinor Morgenthau at the hotdog picnic at Top Cottage in Hyde Park, New York. June 11, 1939

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

1939 New York City Park Commissioner Robert Moses with model of proposed Battery Bridge in 1939. While this Moses project. In the late 1930s a municipal controversy raged over whether an additional vehicular link between Brooklyn and Lower Manhattan should be built as a bridge or a tunnel. Bridges can be wider and cheaper to build, but taller and longer bridges use more ramp space at landfall than tunnels do. A "Brooklyn Battery Bridge" would have decimated Battery Park and physically encroached on the financial district, and for this reason, the bridge was opposed by the Regional Plan Association, historical preservationists, Wall Street financial interests, property owners, various high society people, construction unions, the Manhattan borough president, Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia, and governor Herbert H. Lehman. Despite this, Moses favored a bridge, which could both carry more automobile traffic and serve as a higher visibility monument than a tunnel. More traffic meant more tolls, which to Moses meant more money for public improvements. LaGuardia and Lehman as usual had little money to spend, in part due to the Great Depression, while the federal government was running low on funds after recently spending $105 million ($1.8 billion in 2016) on the Queens-Midtown Tunnel and other City projects and refused to provide any additional funds to New York. Awash in funds from Triborough Bridge tolls, Moses deemed that money could only be spent on a bridge. He also clashed with chief engineer of the project, Ole Singstad, who preferred a tunnel instead of a bridge. Only a lack of a key federal approval thwarted the bridge project. President Roosevelt ordered the War Department to assert that bombing a bridge in that location would block East River access to the Brooklyn Navy Yard upstream. Thwarted, Moses dismantled the New York Aquarium on Castle Clinton and moved it to Coney Island in Brooklyn, where it grew much bigger. This was in apparent retaliation, based on specious claims that the proposed tunnel would undermine Castle Clinton's foundation. He also attempted to raze Castle Clinton itself, the historic fort surviving only after being transferred to the federal government. Moses now had no other option for a trans-river crossing than to build a tunnel. He commissioned the Brooklyn–Battery Tunnel (now officially the Hugh L. Carey Tunnel), a tunnel connecting Brooklyn to Lower Manhattan. A 1941 publication from the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority claimed that the government had forced them to build a tunnel at "twice the cost, twice the operating fees, twice the difficulty to engineer, and half the traffic," although engineering studies did not support these conclusions, and a tunnel may have held many of the advantages Moses publicly tried to attach to the bridge option. This had not been the first time Moses pressed for a bridge over a tunnel. He had tried to upstage the Tunnel Authority when the Queens-Midtown Tunnel was being planned.[19] He had raised the same arguments, which failed due to their lack of political support. alamy.photo wiki info.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Herbert H. Lehman

#suitdaddy#suiteddaddy#suit and tie#suited daddy#men in suits#suitfetish#three piece suit#waistcoat#suited grandpa#suitedman#suited man#buisness suit#suitedmen#americans#democrats#u.s. senate#new york state#governor of new york#Herbert H. Lehman#Herbert Lehman

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Grand Street Boys' Association, "headquarters of those who really love New York"

By Patricia Glowinski, Archivist at the Center for Jewish History

Processed in the Shelby White & Leon Levy Archival Processing Laboratory at the Center for Jewish History (CJH) are the Grand Street Boy's Association Records, just one of the many archival collections of the American Jewish Historical Society, one of the five partner institutions comprising CJH. The collection documents 20th century American Jewish history and New York City history, as they intersect in the activities of the once thriving club whose motto was "Good Fellowship, Benevolence, Charity."

The origins of the Grand Street Boys' Association date back to 1916 when a reunion was held in Manhattan for men who had grown up on or near bustling Grand Street, a main thoroughfare in the Lower East Side. Grand Street in the early 1900s was the center of a large immigrant neighborhood and was home to many Eastern European (many of them Jewish), Italian, and Irish immigrants. The success of that 1916 reunion led to a second reunion in 1920 where it was decided that a permanent club should be formed. The Grand Street Boys' Association was incorporated in 1921 and they opened their first clubhouse in 1924 in the former MacDougal Club, located at 106-108 West 55th Street in Midtown Manhattan. The clubhouse had a gym, lounge, dining room, barbershop, library, and an auditorium.

Mirroring the demographic makeup of the Lower East Side in the early 1900s, original members were primarily Jewish, but were also Irish and Italian, among other ethnicities. Open to all men (and eventually women) regardless of religion, ethnicity, or social class, the Grand Street Boys promoted welfare projects, acts of fellowship and tolerance, scholarships, youth employment, war efforts, and the elimination of discrimination in sports, among other projects. At first, only men who grew in the vicinity of Grand Street were eligible to enroll. This restriction was soon removed and the Association became the "headquarters of those who really love New York."

As documented in the extensive membership records from the collection (See Series 1, Subseries 4), membership spanned all sectors of social class and occupations. Alongside governors, mayors, judges, senators, and famous entertainers were bartenders, furriers, detectives, opera singers, restaurateurs, art therapists, umbrella salesmen, meter readers, and firemen. Well-known members included Irving Berlin, Eddie Cantor, Irving Caesar, Fiorello La Guardia, Al Smith, John Lindsay, Robert F. Wagner Jr., Jonah J. Goldstein, Herbert H. Lehman, Nelson A. Rockefeller, and Cardinal Patrick Hayes.

The collection documents the activities of the Association, as well as the Grand Street Boys' Foundation, its financial arm established in 1945, and its Hobbycraft Program, a charitable program tasked with collecting and redistributing donated items to charitable and nonprofit organizations. Materials include administrative records, financial records, correspondence, minutes, membership records, newsletters, yearbooks, artifacts, and photographs. The collection’s strengths include the membership records, the meeting minutes, the Grand Street Boys’ publications including the newsletter, Wuxtra, and the yearbooks, and the photographs which capture the spirit and essence of the Grand Street Boys' Association during its prime. Below are just a few photos that will (hopefully) inspire researchers to come to the Lillian Goldman Reading Room and use the collection!

1. Boy Scouts with Jonah J. Goldstein, President of the Grand Street Boys’ Association, at the Grand Street Boys’ clubhouse, circa 1960 (Photo credit: New York Times)

2. Irving Caesar (third from left), songwriter and Grand Street Boy, at Colony Records in Manhattan for the publication of the Grand Street Boys’ song, 1960

3. Golden wedding party at the clubhouse showing Mr. and Mrs. Frank Hershkowitz dancing to Jack Snyder’s accordion music, 1959 (Photo credit: Daily News)

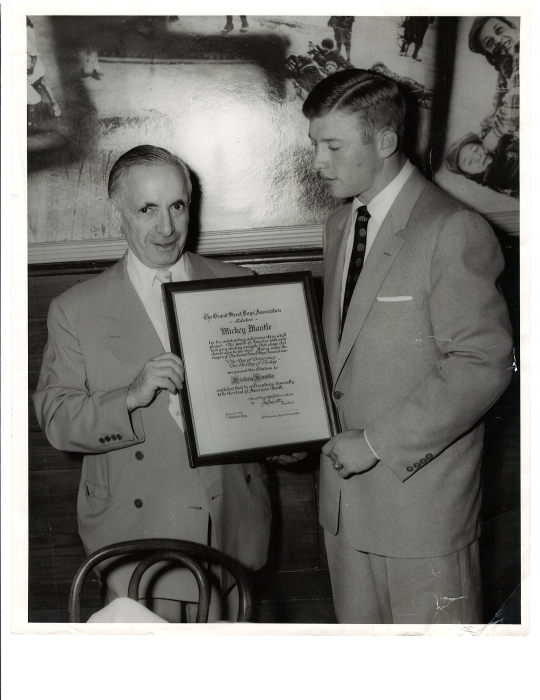

4. Jonah J. Goldstein presenting a Grand Street Boys’ Association award to Mickey Mantle, 1953

5. Grand Street House London showing Sir Louis Sterling (former Lower East Sider and life member of the Grand Street Boys), 1941 (Photo credit: Sport & General Press Agency, London)

6. Gramercy Boys Club, known for its marching band, performing in the auditorium at the clubhouse, circa 1960

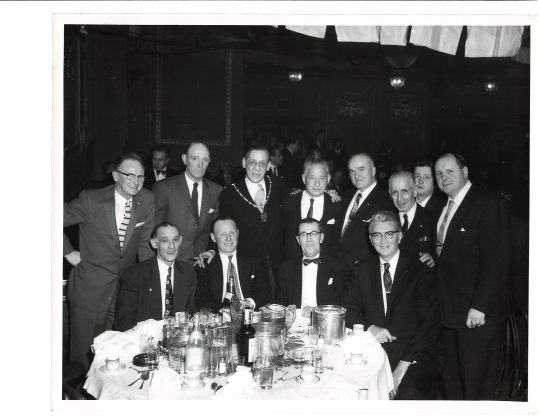

7. Robert Briscoe (standing, 3rd from left), who became the first Jewish Lord Mayor of Dublin in 1956, at a dinner at the Grand Street Boys’ clubhouse, with Abe Stark (standing, 4th from left), Jonah J. Goldstein (standing, 3rd from right), and others, circa 1957

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

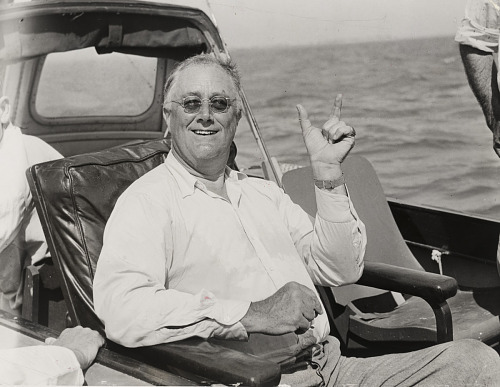

The Triborough (now the Robert F. Kennedy) Bridge opened on July 11, 1936. The span, which links Manhattan, the Bronx, and Queens, was built at a cost of about $50 million (over a billion in 2022 dollars). It was the most expensive public works project of the New Deal, surpassing even that of the Hoover Dam.

The photos above show the distinguished guests at the dedication: Mayor La Guardia (seated, left), New York Governor Herbert Lehman (seated to the mayor’s left), President Roosevelt (standing), and, in the picture on the right, not-quite-ten year old Anthony Benedetto of Astoria. The young boy, who later changed his name to Tony Bennett, marched across the bridge with the mayor, singing “Marching Along Together.” He was rewarded with a pat on the head by the mayor.

Below, the bridge as it looked in the 1950s.

Photo top left: Bettmann Archives/Getty Images. Top right: Tony Bennett/Twitter. Below: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

#New York#NYC#vintage New York#1930s#Triborough Bridge#Tony Bennett#Triboro Bridge#Robert F. Kennedy Bridge#Fiorello LaGuardia#Herbert Lehman#FDR#Franklin D. Roosevelt

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

These Artifacts Were Stolen. Why Is It So Hard to Get Them Back?

In 2004, Steve Dunstone and Timothy Awoyemi stood on a boat on the bank of the River Niger.

The two middle-aged men, both police officers in Britain, were taking part in a journey through Nigeria, organized through the Police Expedition Society, and had reached the small town of Agenebode, in the country’s south. Their group brought gifts with them from British schoolchildren, including books and supplies. The local schools had been alerted in advance, and a crowd came down to the river banks to meet them; there was even a dance performance.

It was a wonderful — if slightly overwhelming — welcome, Mr. Dunstone recalled.

In the back of the crowd, Mr. Awoyemi, who was born in Britain and grew up in Nigeria, noticed two men holding what looked like political placards. They didn’t come forward, he said. But just as the boat was about to push off, one of the men suddenly clambered down toward it.

“He had a mustache, scruffy stubble, about 38 to 40, thin build,” Mr. Dunstone recalled recently. “He was wearing a white vest,” he added.

The man reached out his arm across the water and handed Mr. Dunstone a note, then hurried off with barely a word.

That night, Mr. Dunstone pulled the note from his pocket. Written on it were just six words: “Please help return the Benin Bronzes.”

At the time, he didn’t know what it meant. But that note was the beginning of a 10-year mission that would take Mr. Dunstone and Mr. Awoyemi from Nigeria to Britain and back again, involve the grandson of one of the British soldiers responsible for the looting, and see the pair embroiled in a debate about how to right the wrongs of the colonial past that has drawn in politicians, diplomats, historians and even a royal family.

By the end, Mr. Dunstone and Mr. Awoyemi would have done more to return looted art to Nigeria — with two small artifacts — than some of the world’s leading museums, where the debate over the right of return continues.

World Treasures

The Benin Bronzes are not actually from the country of Benin; they come from the ancient Kingdom of Benin, now in southern Nigeria.

They’re also not made from bronze. The various artifacts we call the Benin Bronzes include carved elephant tusks and ivory leopard statues, even wooden heads. The most famous items are 900 brass plaques, dating mainly from the 16th and 17th centuries, once nailed to pillars in Benin’s royal palace.

There are at least 3,000 items scattered worldwide, maybe thousands more. No one’s entirely sure.

You can find Benin Bronzes in many of the West’s great museums, including the British Museum in London and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. They’re in smaller museums, too. The Lehman, Rockefeller, Ford and de Rothschild families have owned some. So did Pablo Picasso.

Their importance was appreciated in Europe from the moment they were first seen there in 1890s. Curators at the British Museum compared them at that time with the best of Italian and Greek sculpture.

Today, the artifacts still leave people dumbstruck. Neil MacGregor, the British Museum’s former director, has called them “great works of art” and “triumphs of metal casting.”

There’s one place, however, where few of the original artifacts are found: Benin City, where they were made.

That may change. Benin’s royal family and the Nigerian local and national governments plan to open a museum in Benin City in 2023 with at least 300 Benin Bronzes. Currently the site is a bit of land that’s little more than a traffic island.

Those pieces will come mainly from the collections of 10 major European museums, such as the Humboldt Forum in Berlin, the Weltmuseum in Vienna and the British Museum. They will initially be on loan for three years, with the possibility to renew. Or, when those loans run out, other Benin Bronzes could replace them. The museum could become a rotating display of the kingdom’s art.

This hugely complex initiative — organized through the Benin Dialogue Group, which first convened in 2010 — is being celebrated as a chance for people in Nigeria to see part of their cultural heritage. “I want people to be able to understand their past and see who we were,” said Godwin Obaseki, governor of Edo State, home to Benin City, and a key figure in the project.

But is the Benin plan — a new museum filled with loans — a more practical solution than a full-scale return, long called for by many Nigerians and by some activists? That probably depends on what you think about how the Benin Bronzes were obtained in the first place.

Ill-Gotten Gains

On Jan. 2, 1897, James Phillips, a British official, set out from the coast of Nigeria to visit the oba, or ruler, of the Kingdom of Benin.

News reports said he took a handful of colleagues with him, and it’s assumed he went to persuade the oba to stop interrupting British trade. (He had written to colonial administrators, asking for permission to overthrow the oba, but was turned down.)

When Phillips was told the oba couldn’t see him because a religious festival was taking place, he went anyway.

He didn’t come back.

For the Benin Kingdom, the killing of Phillips and most of his party had huge repercussions. Within a month, Britain sent 1,200 soldiers to take revenge.

On Feb. 18, the British Army took Benin City in a violent raid. The news reports — including in The New York Times — were full of colonial jubilation. None of the reports mentioned that the British forces also used the opportunity to loot the city of its artifacts.

At least one British soldier was “wandering round with a chisel & hammer, knocking off brass figures & collecting all sorts of rubbish as loot,” Capt. Herbert Sutherland Walker, a British officer, wrote in his diary.

“All the stuff of any value found in the King’s palace, & surrounding houses, has been collected,” he added.

Within months, much of the bounty was in England. The artifacts were given to museums, or sold at auction, or kept by soldiers for their mantelpieces. Four items — including two ivory leopards — were given to Queen Victoria. Soon, many artifacts ended up elsewhere in Europe, and in the United States, too.

“We were once a mighty empire,” said Charles Omorodion, 62, an accountant who grew up in Benin City but now lives in Britain and has worked to get the pieces returned from British museums. “There were stories told about who we were, and these objects showed our strength, our identity,” he said.

He said that seeing the Benin Bronzes in the world’s museums filled him with pride, as they showed visitors how great the Benin Kingdom had been. But, he added, he also felt frustration, bitterness and anger about their being kept outside his country. “It’s not just they were stolen,” he said, “it’s that you can see them being displayed and sold at a price.”

Insult to Injury

Benin City has been calling for the return of its artifacts for decades. But a key moment came in the 1970s when the organizers of a major festival of black art and culture in Lagos, Nigeria, asked the British Museum for one prized item: a 16th-century ivory mask of a famous oba’s mother.

They wanted to borrow the work, to serve as the centerpiece of the 1977 event, but the British Museum said it was too fragile to travel. Nigeria’s news media told a different story, reporting that the British government had asked for $3 million insurance, a cost so high it was seen as a slap in the face.

That incident is still fresh in some Nigerians’ minds, more than 40 years later. At a recent meeting of the Benin Union of the United Kingdom, an expatriate group that meets at a church in south London, several members brought up versions of the festival incident when asked about the Benin Bronzes. Then they started criticizing British museums, which they said never seemed willing to return stolen items, despite repeated requests.

“I wouldn’t go there,” said Julie Omoregie, 61, when asked if she’d ever been to the British Museum, a half-hour away by subway, to see the mask. It was “an insult” that it was in the museum, she said. When she was a child, she recalled, her father would sing her a song about the raid, and she would cry every time. “It is time for them to give us back what they took from us,” she said.

David Omoregie, 64, another member of the group, said “The British are very good at telling you, ‘We are looking after it. If you’d been looking after it, it would have been stolen by now.’”

He agreed with that once, he said, but he didn’t anymore: “You can leave your car to rot outside your drive; at least it’s your car,” he added.

Some pieces stolen in the raid have gone back to Nigeria from institutions. In the 1950s, the British Museum sold several plaques to Nigeria for a planned museum in Lagos, for instance, and sold others on the open market. But those were not the free, full-scale returns people call for now.

Pressure for those types of returns has grown recently. In 2016, students at Jesus College, part of Cambridge University, campaigned to have a statue of a cockerel removed from the hall where it had been displayed for years. Last November, the college announced that the cockerel must be returned. (It has yet to say when or how.)

In the United States too, students have protested the presence of a Benin Bronze at the Rhode Island School of Design Museum. The museum has said it is looking to return the item, but was struggling to find out whom to actually work with: the Nigerian government, the Benin royal family or others.

But nothing has publicly gone back to Nigeria in decades, except, that is, for two small items. And, that’s thanks, at least in part, to Mr. Awoyemi and Mr. Dunstone.

Heading Back

When Mr. Dunstone got back to England from Nigeria, he couldn’t shake that note from his mind: “Please help return the Benin Bronzes.”

He didn’t even know what they were, he recalled recently, but Mr. Awoyemi did — he’d learned all about them and the 1897 raid as a teenager in Nigeria — and he filled Mr. Dunstone in.

Mr. Dunstone simply couldn’t understand why Britain still had the Benin artifacts, he said. That feeling grew one day when he went to the British Museum to look at its collection. He was blown away by the 50-odd plaques on display, and more so when a security guard told him that there were 1,000 more items in the basement. (In fact, the museum owns around 900 items from Benin, and many are in storage in another building.)

“We really did steal them,” Mr. Dunstone, now 61, said. “We weren’t at war, we turned up and hacked them off the walls.”

In 2006, Mr. Dunstone created a web page about the Benin Bronzes, with Mr. Awoyemi’s input. He added a note at the bottom of the page asking anyone with information about the whereabouts of any items to get in touch. The two men, who became friends as colleagues in the police force protecting the British royal family, even wrote to the oba in Benin and the Nigerian government, asking for permission to act as envoys to Britain’s museums to try and get the artifacts back to Nigeria.

No one replied, Mr. Awoyemi, 52, said. “We were so passionate,” he added, “but we were becoming frustrated with the whole thing.”

Mr. Awoyemi and Mr. Dunstone were just about to give up when, one day, in 2013, an email arrived. It was from a doctor from Wales named Mark Walker. Mr. Walker said he owned two of the looted items: a small bird that used to be on top of a staff, and a bell that had been struck to summon ancestors.

He wanted to give them back.

Mr. Walker, 72, is now retired and spends much of his time sailing. His grandfather was Captain Walker, who described the looting in his diary and took the pieces during the 1897 raid. They were once used as doorstops, Mr. Walker said, but after he inherited them they sat on a bookshelf, gathering dust. They’d be better off in Nigeria with the culture that created them, he said.

“My view is the British Museum should use modern technology to make perfect casts of its whole collection and send it all back,” he said recently. “You wouldn’t know the difference.”

At first, Mr. Walker didn’t want to go to Nigeria, afraid, Mr. Awoyemi said, that he might be prosecuted for having had them at all. But Mr. Awoyemi and Mr. Dunstone convinced him that the publicity from such a bold move could lead others to return items.

The Nigerian Embassy in London agreed to sponsor the trip, but pulled out when Mr. Walker insisted the items had to be returned directly to Benin City and the current oba, rather than to Nigeria’s president, Mr. Awoyemi said.

So Mr. Dunstone and Mr. Awoyemi mounted an amateur public relations campaign, securing appearances for themselves on radio and TV, to help raise the funds and show the royal court in Benin City that they were serious.

It worked.

In June 2014, Mr. Walker, Mr. Dunstone and Mr. Awoyemi headed to Benin City to return the artifacts to the oba.

The ceremony at the oba’s palace was as overwhelming as the welcome on the river bank that had begun the whole journey, Mr. Dunstone said. It was filled with so many dignitaries and journalists, there was initially no room for him.

Mr. Walker said he handed over the objects quickly, without fuss. In return, the oba gave him, just as calmly, a tray of gifts, including a modern sculpture of a leopard head’s that weighed about 40 pounds.

“I was horrified,” Mr. Walker said. “I’d gone all that way to get rid of stuff, not get more.”

Where Next?

If there aren’t more individuals like Mr. Walker on the horizon, looking to give unwanted artifacts back, is the new museum full of items on loan the best Benin City can hope for?

Maybe.

Nigerian government officials have played down the need for items to be permanently returned. Mr. Obaseki, the state governor, said at a news conference at the British Museum last year: “These works are ambassadors. They represent who we are, and we feel we should take advantage of them to create a connection with the world.” His message: Nigeria wants them on display in the world’s museums, not just in Benin City.

Some museums do appear open to returning looted objects permanently, rather than lending them. Last March, the National Museum of World Cultures in the Netherlands launched a policy to consider claims for cultural objects acquired during colonial times.

Nigeria could claim the museum’s 170 or so artifacts from Benin City under the policy, if it proves that the items had been “involuntarily separated” from their rightful owners, or that the items are of such value to Nigeria that it “outweighs all benefits of retention by the national collection in the Netherlands.”

German museums have agreed to a similar policy.

Given how many Benin Bronzes are in Western museums, it seems likely some requests made under those policies would be accepted.

Until the museum in Benin City is built, however, nothing is likely to be returned permanently unless it is done by individuals. No one has a firm idea how many looted items are in private hands, but they used to regularly come up at auction. (The record price, set in 2016, is well over $4 million.)

Mr. Dunstone said he had hoped that dozens of people would have come forward with items to return by now. The ceremony in 2014 received a flurry of media attention, and he went back to England expecting new Mr. Walkers to appear.

It didn’t happen. He got one email from a man in South Africa who claimed to have fished a Benin Bronze out of a river. He was willing to mail it to Mr. Dunstone for $2,500.

Mr. Dunstone, ever the police officer, suspected a scam and didn’t write back.

“I’m less proactive now,” he said. “But my heart’s still open.”

Mr. Awoyemi said he was disappointed, too, that no one came forward, but was excited by the museum plan. He was even willing to help with security, he said, if the oba would let him.

Mr. Walker can’t put the Benin Bronzes behind him, either. A few months ago, he was looking online at Benin Bronzes held by the Horniman Museum in London and came across an intricately carved wooden paddle. It was almost identical to two he had in his home, which he thought his parents had bought on vacation.

Then he realized his grandfather must have looted them from Benin City, too.

In December, he lent the paddles to the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford — a member of the Benin Dialogue Group — with one condition: They had to be returned to Benin City within three years.

He wasn’t going to be getting on a plane with Mr. Dunstone and Mr. Awoyemi this time. “It would be harder to get two six-foot paddles through customs,” he said. He also didn’t want his motives questioned. He’s wasn’t returning the items for glory, he said: They should just go back. It’s the right thing to do.

from WordPress https://mastcomm.com/event/these-artifacts-were-stolen-why-is-it-so-hard-to-get-them-back/

0 notes

Text

The Lehman Trilogy, an inventively staged, extraordinarily acted, and historically blinkered theatrical epic, begins and ends with the collapse of the Lehman Brothers, the venerable financial institution, in September, 2008. But these moments serve as tiny bookends to what is really the main story being told at the Park Avenue Armory – the story of the three Lehman brothers, after their arrival in America in the 18th century.

Hayum Lehmann (Simon Russell Beale) was the first to emigrate from Bavaria, Germany, arriving in New York Harbor in 1844. Quickly changing his name to Henry Lehman, he moves to Montgomery, Alabama and opens a general store that sells fabric and suits. To help him in his business, he brings over his two younger brothers – Emanuel, nee Mendel (Ben Miles) in 1847, and Mayer (Adam Godley) in 1850.

Responding to the needs of their customers, the brothers expand their business little by little – selling seeds and tools to plantation owners; then becoming middlemen, or brokers, between the Southern plantation owners and the Northern mill owners, buying and selling raw cotton. After Henry dies young from yellow fever, and the conflagration of the Civil War, the two remaining brothers convince the governor of Alabama to invest the state’s money in the Lehmans so that they can rebuild the cotton trade and revive the economy. This is how the Lehman brothers become bankers. From there, they also join the coffee exchange, move to New York, invest in railroads, help create the newly built New York Stock Exchange. “A brilliant idea,” the brothers say. Now

instead of negotiating iron at the Iron Market, fabric at the Fabric Market

coal at the Coal Market, they created one market.” For “every type of thing you can imagine” but the things themselves don’t exist – only the words “iron,” “fabric,” “coal.” “A temple of words” – and, left unsaid, the birth of modern capitalism.

The three actors, who begin the play portraying the three Old World Jews in 18th century frock coats, never change costumes to portray all the people with whom the brothers come into contact – including the wives they woo, and the toddlers they sire – and then the succeeding generations of Lehmans who take over the business. Most memorably, these are the frighteningly astute Philip Lehman (Beale), Emanuel’s son; Herbert (Miles), Mayer’s son, whom Philip pushes out of the firm and who acquires a second career as governor of New York; and Bobby, Philip’s smartly modern, mildly hedonistic son (Godley), who takes the firm’s investments in a new consumer-oriented direction – airlines, cigarettes, and motion pictures, including the original (and wildly remunerative) “King Kong.” After the second intermission, the actors portray the non-Lehmans who took over the firm in the last 40 years of its existence, the least engaging of the three acts.

Written by Italian playwright Stefano Massini, who conceived the show in 2012 as a five-hour radio play, the Lehman Trilogy has been adapted into English by Ben Miles for London’s National Theatre. Its narrative feels like a spoken novel; the characters largely talk about themselves in the third person, with only occasional dialogue. Its language resembles a fugue, with poetic repetition and interweaving of phrases. Under the direction of Sam Mendes (artistic director of Donmar Warehouse, Oscar winner of American Beauty, currently represented on Broadway by The Ferryman), it takes on the whimsical feel of a folk tale. It is, in other words, almost anything but a conventional play.

The three and a half hours play out on a stage designed by Es Devlin that looks like something created for a World’s Fair – four offices, complete with conference room, on a floor of a modern corporate office building, contained under a glass cube, which revolves at regular interviews around a turntable set on the shiny stage floor, and placed in front of a huge curved cyclorama with video designer Luke Hall’s ooh-inducing projections of skylines and clouds, and even fiery abstract dreams. Pianist Candida Caldicot unobtrusively underscores the actors’ words with an original composition by Nick Powell.

One need not understand international finance to realize that the creative team was more interested in storytelling and stagecraft than historical accuracy, more focused on the personal stories of the Lehman men than in the wider implications and context of their success. There is, notably, almost no mention of slavery, nor Anti-Semitism. When Henry arrives in America in 1844, the cyclorama has a sweeping view of the gray expanse of Upper New York Bay punctuated by the towering Statue of Liberty.

But the Statue of Liberty wasn’t placed in the bay until 1885, as anybody with an American education would know.

Click on any photograph by Stephanie Berger to see it enlarged.

Simon Russell Beale as Henry Lehman

Adam Godley

Ben Miles

Simon Russell Beale, Ben Miles, Adam Godley,

The Lehman Trilogy

Park Avenue Armory

Written by Stefano Massini. Adapted by Ben Power. Directed by Sam Mendes.

Set design by Es Devlin, costume design by Katrina Lindsay, video design by Luke Halls, lighting design by Jon Clark. Composer and sound designer Nick Powell. Co-sound designer Dominic Bilkey. Music director Candida Caldicott. Movement director Polly Bennett. Cast: Simon Russell Beale, Adam Godley, Ben Miles.

Running time: 3hrs 35mins, including two intermissions.

The Lehman Trilogy is on stage through April 20th.

Completely sold out, but $45 rush

The Lehman Trilogy Review: 164 Years Of One Capitalist Family Minus The Dark Parts The Lehman Trilogy, an inventively staged, extraordinarily acted, and historically blinkered theatrical epic, begins and ends with the collapse of the Lehman Brothers, the venerable financial institution, in September, 2008.

0 notes

Link

Babies were snatched off the streets by strangers in passing cars. Or taken from day-care centers or church basements where they played. Or stolen from hospitals, right after birth, passed from doctor to nurse to a uniformed “social worker” — before vanishing in an instant. Some were dropped into dismal orphanages; others were sent to a new family, their identities wiped, no questions asked. Most would never see their birth parents again. While it sounds like something out of Dickens or the Brothers Grimm, this happened in the United States in the 20th century. Thousands of times. She was the mastermind behind a black market for white babies.It was the dark handiwork of the Memphis branch of the Tennessee Children’s Home Society, a supposedly charitable organization, led by a woman named Georgia Tann. Tann was a pied piper without scruple; she was the mastermind behind a black market for white babies (especially blond, blue-eyed ones) that terrorized poor Southern families for almost three decades. It’s estimated that over 5,000 children were stolen by Tann and the society between 1924 and 1950 and that some 500 died at the society’s hands as a result of poor care, disease and, it is suspected, abuse. Particularly vulnerable were newborns. In 1945 alone, as many as 50 children perished in a dysentery outbreak. The precise figure, like so many terrible details about the society, is not known. Tann had various means of procuring babies and children for her wealthy customers. She bribed nurses and doctors in birthing wards, who would then tell new parents that their babies had been stillborn. MORE ON: ABDUCTIONS Teen girl saves kidnapped man after finding him tied up inside car trunk Man staged abduction to avoid paying Super Bowl debts: cops Cops uncover deadly plot to kidnap child from county fair: cops Homeless dad arrested in alleged abduction of 2-year-old daughter with autism Her organization was quick to snatch babies born in prisons and mental wards. Older children were grabbed off the street by Tann’s agents and were told their parents had died. To cover their tracks, the society falsified adoption records and destroyed any trace of these children’s origins. Lisa Wingate brings these shocking crimes and their long-term emotional impact to light in her affecting new novel, “Before We Were Yours” (Ballantine Books), out now. The book tells the story of two families — the wealthy, connected Staffords and the dirt-poor “river gypsy” Fosses. Though her tale is fictional, it stems from the true, terrible events of the Tennessee tragedy. Tann and her associates would tear apart one family to benefit another, creating wounds not easily healed. The loss would linger, like a phantom limb, for generations. Tann would tell adoptive parents that the children were “blank slates,” Wingate tells The Post. “What really resonated with me is that they’re not. Foster kids, adopted kids, they’re not blank slates. They’re people. And they have genetic tendencies and . . . talents and abilities that are all their own.” Tann’s background was a privileged one. She was born in 1891 in Hickory, Miss., where her father was a district court judge. One of Judge Tann’s responsibilities was dealing with homeless children who were wards of the state. Georgia’s older brother, Rob Roy Tann, may have been one of these children, adopted by the Tann family. Enlarge Image Movie stars including Joan Crawford (left) and June Allyson adopted kids from the society. Tann had designs on a career in the law, but her father deemed that profession too “masculine” for his only daughter. Forced to study music, she taught for a time before finding a job in the nascent field of social work in 1916. Working as a field agent for the Mississippi Children’s Home-Finding Society in Jackson, she may have gotten a taste for the power that she would later wield over so many families. She began placing poor children in adoptive homes, without the consent of both birth parents. Child welfare laws weren’t as strict as they are today, allowing Tann to wheel and deal in her role. But Tann was not careful with her work, nor with covering up her trail, and at least one birth parent sued for return of her children. It seemed Mississippi was not the right market for a baby-resale business. Judge Tann had connections in Memphis, and after a brief foray in Texas, his daughter moved there to work for the Tennessee Children’s Home Society in 1924. Soon after, she launched her adoption racket. To drum up business, Tann placed advertisements aimed at potential adoptive parents in newspapers. One featured a photo of smiling, towheaded infants with the caption, “Want a Real, Live Christmas Present?” As if children were dolls or puppies. Foster kids, adopted kids, they’re not blank slates. They’re people. And they have genetic tendencies and . . . talents and abilities that are all their own. Tann presented herself as a kindly matron and pioneer of a new kind of social work — all the while destroying lives and families. Tann was abetted by the famously corrupt political machine in Memphis, headed by E.H. “Boss” Crump. Crump, also a transplanted Mississippian, was the sometime mayor and leader of politics in the city for much of the first half of the 20th century. He developed a cozy patronage relationship with Tann — she paid him off and brought the fame of her society to Memphis. He in turn protected her from prying investigations, while city police ignored the complaints of families who’d lost children to Tann and sometimes even helped Tann seize kids. Tann’s most useful co-conspirator was Camille Kelley, a juvenile court judge in the city. Like Tann, Kelley pretended to act in the best interests of children. With the stroke of a pen, Kelley would remove parental rights and transfer them to Tann, clearing a path for adoption. Tann was essentially waging class war. She held to the belief that there were two kinds of people: the poor, whom she viewed as incompetent parents, and the wealthy. She fattened her own coffers in the process. The big money came from interstate adoptions, especially to New York and LA, for which the agency would charge as much as $5,000. Most of that fee was pocketed by Tann, who was given to traveling in chauffeured Packards. Among the Tennessee Children’s Home Society’s clientele was that paragon of maternal love Joan Crawford, who adopted her twin daughters, Cathy and Cynthia, through the organization in 1947. Mid-century Hollywood power couple June Allyson and Dick Powell used the agency to adopt their daughter, Pamela. Lana Turner, Pearl S. Buck and New York Gov. Herbert Lehman were also clients. And future pro wrestler Ric Flair was among Tann’s abductees. As word of Tann’s tactics started to spread, even some adoptive parents started to object. But, in many cases, Tann had these people over a barrel — they were complicit in her operation and feared losing their children. Whispers and accusations went nowhere. Enlarge Image The headquarters for the Tennessee Children’s Home Society, where abducted children were adopted by rich families.Special Collections Dept / The Uni For years, she was too prominent, too well connected, for anything to stick. In the mid-1940s, Tann was diagnosed with uterine cancer and could sense that her adoption racket was beginning to unravel. Boss Crump’s political influence was starting to wane. Gordon Browning, a Crump enemy, was elected governor in 1948. When rumors of Tann’s baby racket reached his ears, he saw a way to humiliate his political rival. In the final months of Tann’s life, Browning appointed a special investigator to look into her practices. Such was Tann’s remaining influence that the state’s case against her was announced only days before her death, in September 1950. Even then, the brunt of the accusations against Tann had to do with her pocketing money from a state-funded enterprise, rather than kidnapping. Georgia Tann was 59 years old when she died at home of cancer. She never had to face the music for her terrible crimes. She left no money to children’s causes, nor to the Tennessee Children’s Home Society. The home was closed two months later. Word of Tann’s shocking crimes became national news. “Dead Director Blamed in Baby Black Market,” reported the Chicago Tribune. But though Tann had placed children in every state, few attempts were made at the time to connect birth parents with their children. A version of the Tann story was told in the 1993 made-for-TV movie “Stolen Babies” (Mary Tyler Moore stars as the infamous baby-dealer), and a more thorough account of her crimes can be found in the non-fiction book “The Baby Thief” by journalist Barbara Bisantz Raymond. Shortly after Tann’s death, her co-conspirator Kelley announced her retirement from her judgeship. Protected by the Crump machine, she, too, avoided prosecution and died in 1955 from a stroke. It’s estimated that over 5,000 children were stolen by Tann.Boss Crump preceded Kelley in death by a year. Memphis drivers honor the former mayor by taking Crump Boulevard across town from Route 55 to Route 78. Today, the legacy of Georgia Tann and the Tennessee Children’s Home Society is a painful and complicated one. Ironically, an accidental benefit of her work was popularizing adoption for parents unable to conceive. Before Tann, adoption in the United States was uncommon, but after she became known, the stigma over the practice was largely lifted. At the same time, a damaging legal procedure was put in place: Tann championed the practice of closed, secretive adoptions. Adoption records were sealed, and adopted children were barred from learning the identities of their birth parents. This legislation is still in place in many states. Tellingly, Tennessee was the first state to lift these laws, in 1999. Meanwhile, the emotional cost of Tann’s decades-long scheme is incalculable. Thousands of families were torn apart; parents never saw their children again and siblings were permanently separated. Lisa Wingate’s novel tells of one such family. “If you’d invented that story, it would seem so far-fetched that you would think, ‘That could never happen. Not in this country,’” Wingate says. “And yet, it did, and it did for a long time.” For Wingate, this story “still matters today, because there are still so many kids that need that one advocate, that one place to be, that one person who will step in.” She continues, “We do have to still be watching for things that are not aboveboard or are corrupt, where children are being used for profits of one kind or another. That’s on all of us, as a public.”

0 notes