#FIlipino Military Leadership Book 1 Review

Text

FILIPINO MILITARY LEADERSHIP BOOK 1 (Book Review)

FILIPINO MILITARY LEADERSHIP BOOK 1 (Book Review)

Leadership in a broad context has been defined by various individuals in their respective fields and perspective. Amongst those leadership definitions are at par with the trends and can be co-related with present day leaders, the common notion on how people perceive leadership is through discipline and the capacity to circumvent the perils and circumstances according to what is expected of an…

View On WordPress

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Treading Unchartered Waters: The Philippine Water Crisis Goes On

The Water Crisis of the 1990s

To shed some light on how the water crisis of the Philippines had escalated to staggering proportions in the 1990s, one must dig a little deeper into history. The 20-year Marcos dictatorship had set the climate for water problems and system inefficiencies to prevail when cronies and monopolies in almost every industry, commanded the private and public sectors. Its aftermath left the country in shambles. Despite the initial victory of the 1986 People Power Revolution, it was an uphill battle for succeeding President “Cory” Aquino, having to maneuver around and dissolve long-standing political factions, opponents and corrupt protocols within the government, military and private sector. She also had to deal with a number of coup d’etats, a turbulent power crisis and basically trying to right the grave mistakes of her predecessor, that fixing water problems was not on her immediate list of priorities.

Prior to the 1997 Water Concession Agreements, government-controlled Metropolitan Waterworks and Sewerage System (MWSS) both regulated and distributed water in Metro Manila. Inefficiencies, incompetence and corruption in management pervaded the MWSS. [1]Non-revenue water was at a high of more than 60% due to leaks in pipes and widespread water theft. Metro Manila was experiencing constant water shortages; some areas had no water at all. MWSS’s other problem was financing. They were “deeply indebted to foreign creditors—the debts estimated at almost $900 million” (ADB 2008). Come 1994, it was during the Ramos administration (1992-1998) where President Fidel V. Ramos (FVR) sought to kill two birds with one stone by engaging the private sector to participate in a competitive bidding process which would privatize water, at the same time, resuscitate MWSS from its debts. Winners would handle water distribution, while the MWSS would be reduced to just the regulatory body.

Preparations for Water Privatization

According to a book written by senior civil servant in charge of the privatization, Mark Dumol (2000): After consultation and thorough research on successful water concession agreements done in foreign countries such as in Paris, France and Buenos Aires, Argentina, the Ramos administration patterned the water privatization and bidding process after such successful examples. They also sought technical assistance from multilateral agencies, such as, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and The International Finance Corporation (IFC) which is part of the World Bank, to help draft the terms of reference and budget.

Firstly, the Ramos administration began the tedious process of revamping MWSS’s leadership and employees and fixing internal operations to make MWSS efficient, and thus, attractive to bidders. Secondly, they also carefully designed the criteria and qualifications of the bidders that would be of the highest standards, and once they procured these pre-qualified bidders, they then proceeded with a transparent, fair and highly-publicized competitive bidding process. Below are excerpts from Dumol (2000):

Change in leadership and reduction of employees at MWSS

“In 1995, because of certain controversies, President Ramos decided to relieve the current MWSS Administrator. The President also asked the entire Board to submit their courtesy resignations.” FVR was then able to convince the highly respected and competent Angel Lazaro III to take on the role of Administrator (Dumol 2000). Moreover, “based ADB data, MWSS was, in fact, one of the most overstaffed water utilities in the region…Ordinarily, civil service rules would have made it difficult for to reduce the labor force. Fortunately, the [2]Water Crisis Act was the godsend. The Act provided MWSS with the legal basis to reduce its workforce. MWSS worked with labor and came out with an attractive compensation package. The package was so appealing that more than 30% of the employees accepted it” (Dumol 2000).

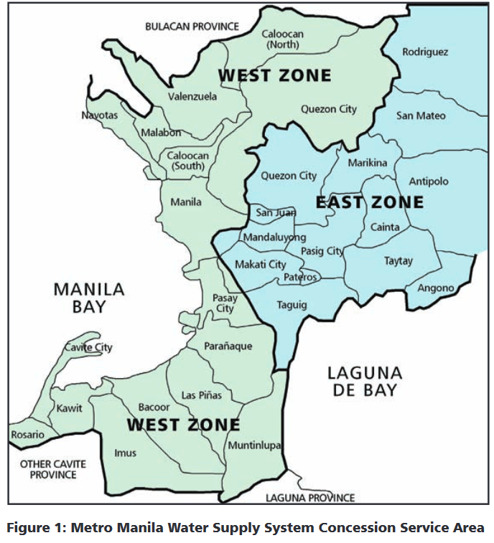

Splitting the Franchise Area into Two Zones

The idea to split the franchise area of Metro Manila into two zones – the East and West Zones, was supposedly inspired by what transpired in Paris. “It was explained to [the Ramos administration] that Paris was split into two zones: the left and right banks of the Seine River. The two concessionaires were the two large French water companies, Compagnie Generale des Eaux and Lyonnaise des Eaux. Intuitively, this model was appealing because of the quasi-competition that it fostered. Consumers could compare service quality of the two concessionaires. Each company would try to outdo the other. There would also be some benchmarks or comparisons between the two zones” (Dumol 2000). However, the differences between the two zones, in terms of residents’ demographics, population and other socio-economic factors, also resulted in differences in water tariffs. This too gave way to some difficulties later on.

The East Zone comprises 23 cities and municipalities. “They are Makati, Mandaluyong, Pasig, Pateros, San Juan, Taguig, Marikina, most parts of Quezon City, portions of Manila, and 14 areas in the province of Rizal” (Rivas 2019). The West Zone comprises 17 cities and municipalities. “It covers most of Manila, areas in Quezon City, areas in Makati, Caloocan, Pasay, Parañaque, Las Piñas, Muntinlupa, Valenzuela, Navotas, and Malabon, as well as Bacoor, Imus, Kawit, Noveleta, and Rosario, which are in Cavite province” (Rivas 2019).

Figure 1. Source: ADB 2008

Pre-Qualified Bidders

The final roster was composed of international water operators and local lead firms, but the Ramos administration “made it clear to all the bidders that the winning concessionaires need to be 60% Filipino-owned and that management of the firm had to be in Filipino hands” (Dumol 2000). They are as follows:

1. International Water (composed of United Utilities of the United Kingdom and Bechtel Corporation of the United States) and Ayala Corporation

2. Lyonnaise des Eaux (France) and Benpres Holdings (The Lopez Group)

3. Compagnie Generale des Eaux (France) and Aboitiz Equity Ventures (AEV)

4. Anglian Water International (United Kingdom) and Metro Pacific Corporation.

The Winners

The actual bidding day was held on January 23, 1997. “Ayala and Lopez-led Benpres both won the bidding and formed Manila Water and Maynilad Water Services, respectively. They got not only contracts, but also absorbed MWSS's debts. Manila Water took the East Zone, and Maynilad got hold of the West Zone” (Rivas 2019).

The 1997 Water Concession Agreements

“The 1997 Water Concession Agreements and the MWSS were mandated to enter into PPP arrangements under Republic Act No. 8041. It entered into two concessions for water, wastewater and sanitation services, one for West Zone (Manila Water) and one for East Zone (Maynilad). Each concession was for 25 years with ambitious performance targets.” Firstly, “the concession agreement called for the two concessionaires to provide 24-hour water supply that meets water quality standards and maintains certain pressure levels” as stipulated in the contract. It also bound the “concessionaires to the following service connection targets (Figure 2):” (ADB 2008)

Figure 2. East and West Zone: service connection targets. Source: ADB 2008

Below are other related main points of the contract with regards to services and tasks to be rendered:

A. To undertake nationwide consultations on the water crisis and in depth and detailed study and review of the entire water supply and distribution structure;”

- To establish the foundation of the water supply

B. To enhance and facilitate cooperation and coordination between Congress and the executive department in formulating and implementing the government's water crisis management policy and strategy;”

- To make it clear the responsibility and who is going to execute

C. To recommend measures that will ensure continuous and effective monitoring of the entire water supply and distribution system of the country;”

- To set up Q&A and monitoring rules for the system

D. To conduct continuing studies and researches on policy options, strategies and approaches to the water crisis including experiences of other countries similarly situated, and to recommend such remedial and legislative measures as may be required to address the problem.”

- To expand the learning and strategy for the act

Secondly, another important provision in the contract that has become a primary point of debate through the years is what is known as [3]rate-rebasing. It is the process by which the private concessionaires can increase or change water tariffs based on certain circumstances, such as, but not limited to, “adjustments based on inflation (CPI) and price adjustment covering extraordinary events” (ADB 2008). According to a political and economic blog by Padilla (2009), “the concessionaires are entitled to adjust their basic rates every five years throughout the contract to achieve a guaranteed rate of return. During the rate rebasing exercise, the concessionaires submit their previous five-year performance, their new five-year business plans and their proposed tariffs to implement it, which the [4]MWSS-Regulatory Office (MWSS-RO) reviews and approves” (Padilla 2009).

As a result, revenue assumptions and efficiencies to be achieved in the short-term were overly optimistic and ambitious. In the months and years that followed, unprecedented events such as the Asian Financial Crisis which caused foreign exchange issues, caused both conglomerates and the MWSS to eventually agree to tariff increases. This will be discussed shortly.

Thirdly, the concessionaires also “had to service MWSS’s foreign debt through annual payments of concession fees and the posting of a USD 120 million performance bond. Given that the West Zone had the more developed infrastructure and larger customer base…[they] were assumed to require less capital infusion. Maynilad was made responsible for paying back 90% of MWSS’s debts (approximately USD 800 million).” History will later show us that “this skewed division of foreign debt service responsibilities was a major contributor to Maynilad’s downfall” (ADB 2008).

Issues that emerged in the years that followed

The 1997 Asian Financial crisis (1997-1998)

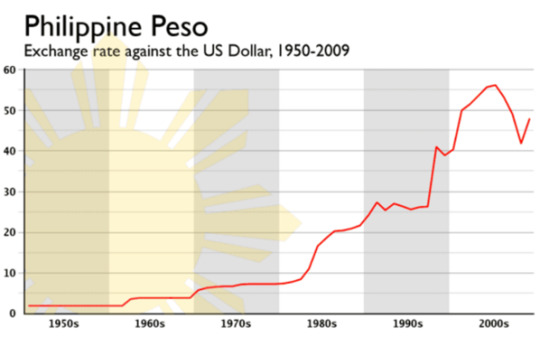

The tail-end of the Ramos administration was plagued with complications brought about by the advent of the [3]Asian Financial crisis in July 1997. Also known as the “Asian Contagion”, the Philippine Peso (Php), along with the Thai Baht (THB) and several other Asian currencies, suffered a tremendous devaluation against the USD. The USD/Php went from Php 26 to Php 41 in a single year, a 57.69% change, and then to Php 50 the following year, for a total of a 100% change in two years. Actually, compared to our counterparts in the region, the Philippines was already little better off, yet one disastrous effect was that entities who had borrowed heavily in USD, experienced rates soaring to almost 20%. Most found themselves unable to repay their foreign debt, especially if they were not USD-earning firms. Among these firms in deep financial trouble due to their inherited USD debt, coupled with the wrong management decisions, was the Lopez contingent of Maynilad.

According to an excerpt from a book appropriately entitled, A Tale of Two Concessionaires: A Natural Experiment of Water Privatisation in Metro Manila, Wu & Nepomoceno (2008) wrote, “Maynilad incurred high costs, in part because it awarded contracts to affiliates of Suez without competitive bidding. It also brought in new staff from its mother-company Benpres, who were inexperienced in water supply…Maynilad thus invested in expanding access in the Western zone, but due to its business model and the heavy load of inherited foreign-currency debt, it soon ran into financial difficulties” (Wu & Nepomoceno 2008).

Figure 3. USD/Php rates, 1950-2009. Source: The Coffee Blogspot

The Estrada Administration (1998-2001)

Sure enough, Maynilad found themselves in trouble. “In an effort to recover from foreign exchange losses, Maynilad petitioned for tariff increases and was granted an extraordinary price adjustment in 2000” (ADB 2008). However, increased water tariffs still could not cover their losses. “By April 2001, Maynilad stopped paying the concession fee to the government altogether. To avoid bankruptcy, the government had to provide financing from state-owned Filipino banks to MWSS. International banks were unwilling to lend to Maynilad after the Financial Crisis, and the owners were not willing to inject more equity” (Wu & Nepomoceno 2008). Investors, globally and domestically alike, were also naturally jittery and risk-averse during these years due to the instabilities brought about by the administration’s controversies such as, the [4]1999 BW Resources stock manipulation scandal and the double homicide case of Emmanuel Corbito and Bubby Dacer. All of which the President “Erap” Estrada was allegedly involved with, ultimately leading to his Impeachment Trial in 2000. These events had further undermined the credibility and integrity of the Philippine economy.

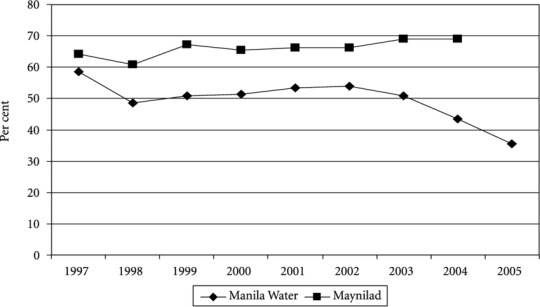

In contrast, Ayala-led Manila Water engaged in the complete opposite of what the Lopez Group had done, and their success was said to have been achieved and sustained through innovation, “corporate governance practices and prudent financial management” (Wu & Nepomoceno 2008). They were able to “reduce their non-revenue water significantly from 58% to 35%, whereas in the West Zone non-revenue water increased from 64% to 69%. Manila Water initially did not invest in system expansion in its Eastern Zone. It focused on reducing non-revenue water and initially borrowed only small amounts in local currency. It bid out works competitively and gained the trust of former MWSS employees who were trained in relevant fields. Only a few top positions were filled with outsiders seconded from its mother-company, Ayala, or its foreign partners. Manila Water used a "territory management" approach to reduce non-revenue water, under which decentralized operating units were responsible for decisions about appropriate actions. Staff evaluation and compensation were linked to their performance” (Wu & Nepomoceno 2008).

Figure 4. Non-revenue water (NRW), Manila Water and Maynilad. Source: MWSS Regulatory Office

Arroyo Administration (2001-2010)

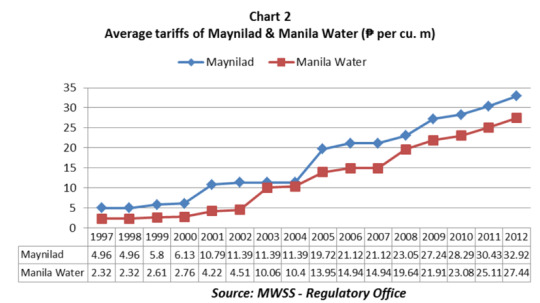

“In the first 5 years of the concession agreement, water tariffs remained low, until the first actual rate-rebasing took place in 2002” (Freedom from debt Coalition 2008). Maynilad’s rate hike was substantially higher than that of Manila Water (Figure 5). This stark discrepancy was already the foreshadowing of what was to happen next. To make the long story short, Maynilad eventually went bankrupt in 2003, and in 2006 (finalized in January 2017), 84% of their stake was acquired by (through competitive re-bidding) to the consortium of DM Consunji Holdings, Inc (DMCI) and Metro Pacific Investments Corporation (MPIC). The “new Maynilad” also then underwent a grueling corporate restructuring. (ADB 2008)

Figure 5. Historical average tariffs of Maynilad and Manila Water, 1997-2012

It was also during this term that President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo (GMA) extended the water concession agreements to the year 2037. The 25-year contracts were supposed to end by 2022, but GMA believed that her foresight to foster continuity would push both conglomerates to make better long-term investment plans and inject more capital into their businesses. The effects of this decision will be discussed below.

Aquino Administration (2010-2016)

Again, another round of disagreements on water tariffs emerged between the conglomerates and the Philippine government during the Aquino administration, and thus, they went into arbitration in Singapore to settle the dispute. However, it was only in 2019, during the Duterte administration where the Tribunal of Singapore had ruled in favor of both Maynilad and Manila Water. This will also be further discussed in depth below.

Current Issues in the Duterte Administration (2016-Present)

The 2019 Water Crisis

It was in March 2019, when another water crisis struck Metro Manila. Water services were suddenly cut off last March 7, 2019, and homes almost everywhere did not have water for an extended period. These water interruptions brought into question the efforts of the 1997 Concession Agreements of Manila Water and Maynilad, and where we are today in terms of the state of the country’s water services. An article from Rappler aimed to explain the reasons behind the recent water shortages. Rivas (2019) wrote, “Both Maynilad and Manila Water draw the water they supply from the Angat Dam, which is located in Norzagaray, Bulacan. Angat Dam supplies 96% of the water demands of Metro Manila. The dam lets out 4,000 million liters per day (MLD) for both Maynilad and Manila Water, where 2,400 MLD is allocated to Maynilad, while Manila Water gets 1,600 MLD. From Angat Dam, water flows to Ipo Dam, then to La Mesa Dam in Quezon City” (Rivas 2019). However, Manila Water is experiencing difficulty keeping up with the demand, as demand has gone up to an average of 1,740 MLD, higher than the company’s Angat Dam allocation of 1,600 MLD. This said deficit was then supplied by water from the La Mesa Dam, but the country then experienced El Niño in March as well which further exacerbated the situation. (Rivas 2019) While Angat Dam’s water level is still normal at over 200 meters, La Mesa dam’s level is already very problematic” (Rivas 2019). Because of the low water level of La Mesa Dam, water can no longer reach the gates of the aqueducts, as illustrated below:

Figure 6. La Mesa Dam. Source: Rappler

During that critical period, Manila Water deployed floating pumps to draw out water from the dam. They also said that they planned network adjustments to balance water supply allocation across distribution areas. However, they also admitted that they assumed customers would collect water only during regular hours, but when the advisories were sent out, the demand surged even from areas not covered in the announcements. The demand surge greatly reduced water pressure and supply levels across the distribution network. Consequently, reservoir volume in several areas dropped below minimum level, preventing water supply from reaching elevated communities. These events, per Manila Water, had caused the service interruptions – particularly in communities that did not get advisories.

The facts on increased demand are also supported by MWSS Chief Regulator, Atty. Patrick Ty, in a statement where he said, “the population keeps increasing, and [Manila Water] can’t reduce their non-revenue water below 12% anymore (international standard is 20%).” According to Manila Water, they had already predicted as early as 2010 that water supply would be insufficient, given the population boom in the capital. In fact, they said that the crisis could have happened in early 2018, but a typhoon somewhat "saved" the city and filled up the dams with much-needed water. Manila Water also indicated that they had proposed several projects and potential water sources, but these were not green-lighted by government One of these projects is the Kaliwa Dam which will be discussed shortly.

As an immediate solution to above-mentioned water shortage crisis, President Duterte ordered the MWSS and water concessionaires to “release” water from Angat Dam good to for 150 days. It was reported that water services improved since these government interventions and also with help of Maynilad. Maynilad also gave an additional 10 MLD of their raw water allocation from Angat Dam, but Maynilad cannot keep allotting their allocations to Manila Water. They also “need their allocation or else there might be water interruptions in the western side…Their non-revenue water is at 40%, but they need to reduce it to 20%, and they are safe” (excerpt from Atty. Patrick Ty, MWSS Chief Regulator).

Manila Water has also since then, activated its new water facility in Cardona, Rizal. The facility will eventually provide a total of 100 MLD once fully operational. Additionally, San Miguel Corporation’s Bulacan Bulk Water has also stepped in by providing potable water from its untapped 140 MLD through trucks and in coordination with local government units and MWSS. (Rivas 2019)

Arbitration Award that angered President Duterte

Months after the March 2019 water interruptions, on November 29, 2019, Manila Water made a public disclosure through the Philippine Stock Exchange (PSE) regarding the arbitration proceedings they (as well as Maynilad) underwent during the Aquino administration:

“Please be informed that Manila Water Company, Inc. (“Manila Water” or the “Company”) has received from its legal counsel the Award (the “Award”) rendered by the Arbitral Tribunal (“Tribunal”) in the arbitration proceedings between the Company and the Republic of the Philippines (the “Republic”) constituted under the Permanent Court of Arbitration (“PCA”), with proceedings held in Singapore.

As it turned out, the Tribunal in Singapore had ruled in favor of Manila Water that they have a “right to indemnification for actual losses suffered by it on account of the [Philippine government’s] breach of its obligation. The Tribunal ordered the [Philippine government] to indemnify Manila Water the amount of Php 7,390,000,000, representing the actual losses it suffered from June 1, 2015 to November 22, 2019, and to pay 100% of the amounts paid by Manila Water to the PCA and 85% of Manila Water’s other claimed costs” (Romero 2019).

The timing of Manila Water’s announcement could not have been worse, as people were still somewhat reeling from the effects of the March 2019 water interruptions. Their pronouncement also called attention to the 1997 water concession agreement. A few days after the above disclosure, a very furious President Duterte lashed out at the media, threatening to file charges of “economic sabotage” against, not just Manila Water, but Maynilad as well, citing that the concession contracts of the two companies are disadvantageous to the public because they prohibit the government from adjusting water rates. (Romero 2019)

In a separate news article, as reported by Business Mirror in December 5, 2019, Manila Water released a statement to hash out the details of the arbitration results, as it seemed to be not well-understood by the general public and the Duterte administration. They explained that the 1997 Concession Agreement contained a procedure for the adjustment of water rates in accordance with the MWSS Charter because “MWSS decided to pay our services and reimburse our costs with the water tariff that we collect…The arbitral award issued in our favor is for acts in breach of the procedure committed by officials of the previous administration, not the Duterte administration.” Manila Water also said that they “wish to reiterate that [they] are more than willing and has started to work with the incumbent administration to come up with a workable solution to the arbitration decision” (BusinessMirror 2019).

However, what came as a shock only a few days later, in a calculated move to appease President Duterte and perhaps maintain good public image, Manila Water made a stunning announcement. They waived their right to collect the amount rewarded to them from the Arbitral Tribunal of Singapore. They released another disclosure dated December 11, 2019:

1. The Company will no longer collect the Php 7.39 Billion Award rendered by the Arbitral Tribunal in the arbitration proceedings between the Company and the Republic of the Philippines constituted under the Permanent Court of Arbitration.;

2. The Company will defer the implementation of the Approved Rate Adjustment effective 1 January 2020 and has signified its intention to establish a suitable arrangement with the Metropolitan Waterworks and Sewerage System (MWSS).

3. The Company has agreed to and started discussions with the MWSS on the provisions of the Concession Agreement identified for renegotiation and amendment.

Nevertheless, the President was still dissatisfied. He was on a witch hunt of sorts and still gave out marching orders to the Department of Justice (DOJ) to look into the 1997 concession contracts, and if they still indeed took hold. Valente (2019) of The Manila Times reported that [9]MWSS Administrator (Ret) Lt. Gen. Emmanuel Salamat stated that, “The MWSS and the concessionaires will exert all necessary efforts to comply with the directive of the President to execute a new water concession agreement after 2022 which is currently being drafted by the Department of Justice” (Valente 2019). After which, the MWSS revoked a board resolution created during the Arroyo administration that extended the contracts of the two firms from 2022 to 2037. It still remains to be seen if this is the final ruling. However, it is important to note that Salamat, made it clear that the 25-year concession agreements with Manila Water and Maynilad remained “valid and subsisting contracts.” He added that “this particular action of the board does not result in the rescission or outright cancellation of the said contracts, which requires a separate and distinct act to be legally effective” (Valente 2019).

“Onerous” Provisions?

The MWSS as the regulatory body, had also been given the directive to renegotiate the concession agreements with Manila Water and Maynilad to remove the supposed “illegal and onerous provisions” which were determined by the DOJ. Other provisions that are to be beneficial to the consumers and the entire nation should be added as well. The alleged seven onerous provisions are as follows:

1. Water concessionaires were called “agents” instead of “public utility companies” when they are managing “public water”. This interpretation allows them to pass on to consumers their business expenses, including corporate income taxes. Unfortunately, the “legal interpretation” is still pending today in the Supreme Court.

2. The “mere agents” explanation allows these companies to increase their return on investment to more than 12 percent (an imposition on public utility companies such as Meralco).

3. Extension of the concession agreement even before the lapse of the original term. Water concession contracts extended in 2009 by 15 years by then President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo or exactly 13 years before these were set to expire in 2022.

4. In the concession agreement, the national government or even Congress can’t interfere in water rate increases or the “yearly rate rebasing”

5. Concession agreement assign exclusively to the MWSS Regulatory Office the burden of overseeing the concessionaires’ operations. The regulatory office is purely recommendatory and unable to impose fines and penalties on erring concessionaires.

6. Both water companies fail to build adequate “sewerage facilities” in the last 22 years. In fact, the Supreme Court, by a 14-0 vote, fined each of them P921,464,184, on top of a daily fine of almost P322,102 subject to a 10-percent increase every two years.

7. The original and extended concession agreements allow “government guarantees” for both Maynilad and Manila Water.

Maynilad and Manila Water, being called as “agents” rather than “public utility companies” had certain implications on various areas such as taxation and revenue generation. Looking further into the ability of the water concessionaires’ ability to pass on their corporate income tax obligations to water consumers, while it is not illegal to do so, it is highly unusual for an entity dealing with public utility such as water to have this kind of ability. Furthermore, since they were dubbed as mere “agents”, they were allowed to establish more than 12% returns, as compared to other public utility entities like Meralco.

In the Concession Agreement, an applied discount rate (ADR) was included which basically granted the water concessionaires a guaranteed rate of return on their expenses. It was even stipulated that rates should be “set at a level that will permit the Concessionaire to recover over the 25-year term of the concession operating, capital maintenance and investment expenditures efficiently and prudently incurred, Philippine business taxes and payments corresponding to debt service on the MWSS loans and concessionaire loans incurred to finance such expenditures, and to earn a rate of return on these expenditures for the remaining term of the concession.”.

Political Motivations and Tactics

President Duterte’s threats to outright cancel the contracts of Manila Water and Maynilad, and instead, either open the field to new entrants or re-nationalize water are highly questionable and politically-charged. His ulterior motives must be assessed. There are many sides circulating about this. One opinion is that Duterte again, seems to be playing the populist; he wishes to appear to the public that he wants to lower water prices. However, the real case is that he is just really extorting money from the Ayalas in the guise of a pro-poor crusade. Secondly, another likely theory is that he is resorting to these tactics to divert public interest from another recent controversy – where the United States has canceled the visas of officials responsible in the alleged rigged proceedings and detention of Senator Leila de Lima.

Nonetheless, both scenarios: maintaining the privatization of water concessions or re-nationalizing water in Metro Manila are issues that should be open to discussion.

Maintaining the privatization of water concessions

The Advantages

The privatization of the MWSS’s water distribution leg was considered the solution to the then government-corporation’s poor service delivery performance of supplying water in Metro Manila, as well as the answer to the country’s huge foreign debt. The Ramos administration opened the water system to the concessions that offered distribution expansion, new water supply sources and a water system with reduced leaks (Dumol 2000).

To end the privatization of water in the Philippines means the country will revert to what it was prior to the 1997 Water Concession agreements. To delve into history again, before the privatization, MWSS maintained 825,000 water connections serving a total population of 7.21mio with 66.5% coverage, but billed only about 42.7% of its 3,000 million liters daily water production. Water availability averaged 17 hours daily, while non-revenue water stood at more than 60%. Back then, around 1.27 million or 11% of the population belonged to the poverty threshold of income. Of the low-income households, 80% had no legal water connections because they have no legal claims over the land they occupy. In the absence of legal piped water connection, people resort to buying from vendors or from those with legal water connection. Some drew water from wells, others even waited for the rain, but most resorted to illegal connections (Yu 2002). The reasons for its incompetence can be explained by its internal management. It was inefficient, overstaffed and suffering from very high water losses. According to the ADB, non-revenue water was more than 60% (McIntosh & Iniguez 1997). Tariffs were also low, and MWSS depended on government subsidies that were to be to abolished. Furthermore, they were burdened with a debt of USD 800 million owed to three major international banks: ADB, the World Bank and the Japan Bank of International Cooperation (Freedom from Debt Coaltion, 2009).

The competitive bidding process of 1997 which produced the winners: Ayala-led Manila Water and Lopez-led Maynilad was essentially deemed a success. However, five years after the concession agreement, improvements in terms of access were still limited and water losses even increased in West Manila. It was only around 2009, almost 12 years later, that performance improved in both the East and West Zones. In 2009, access had increased substantially, and efficiency and service quality had also improved significantly. Both companies also made efforts to reach the poor in the slums. However, tariffs also increased significantly, and said improvements still supposedly remain below the contractual obligations. (Marin 2009)

Today, the Philippines has come a long way since its pre-concession years. Despite some hiccups along the way, it is evident that privatizing water was the right decision. Below are the advantages of maintaining the water concession, based on what it has brought into improving the water systems in Metro Manila.

Improving Access

One of the most important advantage of maintaining the concession agreement is that it would sustain the access that the citizens of Metro Manila to clean water despite the surge in demand, limited resources and the El Nino Crisis. In East Manila between 1997 to 2009, the population that was served by the concessionaires doubled from 3 million to 6.1 million and the share with access to piped water increased from 49% to 94% (Marin 2009). While in West Manila, Maynilad claims to have connected 600,000 people to the water supply including many poor in the slums (Grefe 2003), the share of customers with 24-hour water supply increased from from 32% to 71% in early 2011, while the share of the population with access to piped water increased from 67% to 86% in 2006 (Marin 2009). Maintaining the concession is preserving the water access that the concession has already established over the years. It will not promise a water-crisis-free Metro Manila given that the demand will continuously increase, but it will ensure that the access will not be discontinued.

Sanitation and Waste Management

Another advantage of maintaining the concession is that it allows continuous innovations on wastewater management. Sanitation remains to be a key priority for the concessionaires. They are obliged to empty the 2.2 million septic tanks of Metro Manila by operating 60 desludging trucks that empty septic tanks for free (Manila Water 2012). As of 2012, Manila Water operates 36 small wastewater treatment plants designed to keep costs low with a total capacity of 0.135 million cubic meters per day. This is part of Manila Water’s “innovative and unconventional solution”. Manila Water is also licensed to package bio-solids or treated sewage sludges from its wastewater treatment plants as soil conditioners. Moreover, Manila Water has further plans on improving wastewater treatment capacity in its service area to 0.5 million cubic meters per day (Manila Water 2012).

Perhaps it can be argued that the sanitation efforts of both Maynilad and Manila Water, still remain to not be wholly sufficient after more than 20 years of service, but there is continuous development and improvement of wastewater management. Innovations to further improve the wastewater treatment will only be possible by maintaining the concession agreement because the concessionaires have already invested and initiated the projects.

Employment

Maintaining the concession agreement will also continuously contribute to the employment rate of the Philippines. Before the concession was awarded, government-controlled MWSS “had been one of the most overstaffed utilities in Asia with four times more employees per connection that other neighboring countries” (Dumol, 2000). Further improvements in labor productivity were achieved during the concession by increasing the number of connections without hiring new employees. In 2011, Manila Water was the first Filipino company to win the Asian Human Capital Award because of their improvement in employee management in terms of modernizing its management practices (ABS-CBN News 2011). Both concessionaries have contributed to the improvement of employment rate in the Philippines, while discontinuation of the concession agreement will displace numerous Filipino workers.

Connecting the Poor

Another advantage is of maintaining the concession is the continuous projects for the urban poor. Innovative solutions have also made its way to many poor Filipino citizens who do not have access to piped water supply because the land where they live is occupied illegally. In the East Zone for example, Manila Water’s approach to connect poor communities usually involved no pipes inside communities, but they have included a single bulk meter for up to 100 households. The community is then responsible to connect its members, and any losses beyond the bulk meter will not be incurred by the utility (Xun & Nepomuceno 2008). In the West Zone, Maynilad has initiated early attempts to connect the underprivileged in slum areas through the construction of piped networks via a small local company called Inpart Waterworks and Development Company (IWADCO), using its own funds and buying water in bulk for utilities. This was in partnership with the NGO, Streams of Knowledge, and together they were able to set up a discounted bulk rate for the less fortunate in those areas. The process is like this: Users pay their bills to water coordinators from the respective communities, which in turn pay Streams, which in turn pays a salary to the coordinator, pays the bulk water bill and returns part of the funds to the community (Yolanda & Mejia 2008). Piped networks were also installed in narrow alleys by Maynilad. Residents then distribute it among themselves with a rubber hose. This costs Php5,000, and can be paid via installment by the whole community, which is approximately Php 200 per month per household. This is about four times less than the underprivileged had to pay to water vendors pre-privatization (Grefe 2003).

Expertise, Efficiency and Economic Impact

To contrast the main advantages of maintaining the privatization of water versus to re-nationalize, according to a 2007 article on Water Privatization in Manila, Chia said it best when he wrote, “It is highly unlikely that the government can be more successful in the future in infrastructural provision, as they are encumbered by:

· irrational pricing policies to please voters;

· lack of arm’s length accountability;

· use of these public companies for political and self-interested motives;

· lack of fiscal resources and

· lack of know-how, efficiency and profit-seeking inclination”

The above points could not be any truer, especially for a country like the Philippines where so many issues have surfaced throughout history when projects are left to the machinations of the government alone. It is true that the private sector may have the motive of profit, but we know that they will still serve the Filipino people with more efficiency and competency than the government.

According to Filipovic (2005), “privatization plays an important role in economic growth because it may induce productivity, improve efficiency, provide fiscal relief and increase the availability of credit for the private sector.” It fosters competition and progress. As we can recall, the Ramos administration studied successful examples of foreign countries who privatized water, and then patterned the privatization process and 1997 Water Concession Agreement after such. As the Philippines aspires to one day become a developed nation, the importance of sustaining the water supply should always be a priority. For example, one of the United Nation’s developmental goals is ensuring environmental sustainability which includes reducing the number of people living without sustainable access to safe water. (UN 2008) This can serve as a guide to the Philippines that “for any [nation] or city, long-term sustainability of water services depends on, to a large extent, on the success of appropriate tariff policy and tariff revenue collection to cover costs, loans, and new developments to meet new demands. Non-revenue water must be constantly managed, as it affects revenue collection; thus, it can reduce net revenue and undermine project sustainability. Other factors that affect sustainability include the role of the regulatory office; maintenance of water production; financing of additional supply; timely tariff adjustment; responsible management of the concessionaires; and other sources of water supply (ADB 2008).

The Disadvantages

Continuous Increases in Water Tariffs

Maintaining the privatization of water has its downsides, specifically in how our two water concessionaires are perceived to have opportunistic tendencies. For example, earlier, it was already discussed how “in the first 5 years of the concession agreement, water tariffs remained in low levels until the first rate-rebasing took place in 2002. The significant increase continued and reached up to 89% higher than the pre-privatization tariff” (Freedom from debt Coalition 2008). Realistically though, perhaps such continuous adjustments are inevitable and will occur anyhow, whether water is privatized or nationalized, due to changes and fluctuations in the market and economy, such as inflation, interest rates and exchange rates. We understand however, that affordability remains the critical issue for impoverished communities and the underserved. With limited supply options and low bargaining power, unconnected urban poor households pay high prices monthly. Tariffs will continuously increase, as the two concessionaires charge higher water rates each year. This is a burden on the citizens of Metro Manila, especially the poor, but it is something that perhaps can be monitored or mitigated, but not entirely eliminated. (Chia, et al., 2007)

Water Monopolies and the Pursuit of Profit

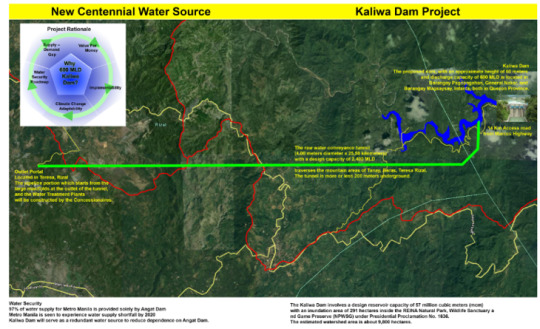

As Maynilad and Manila Water are private companies, we cannot discard the fact that ultimately, their priority is to generate profit from the water concession. These private conglomerates control the timelines in implementing improvement plans and may not necessarily have the urgency to meet the needs of the growing population. Improving water connection for the poor is also not their priority, and they have the power to delay such, if deemed not profitable or important. When it also comes to environmental or sanitation concerns, the importance of these issues may come last versus profit when it comes to the concessionaires’ discretion where to park or construct related projects. Such decisions can compromise the safety of water and quality of life overall, in Metro Manila and surrounding communities. For example, the recent heated topic is the Kaliwa Dam project which has long been delayed because it is embroiled in various social, political and environmental issues. Some of the issues are that indigenous peoples in the area like the Dumagats and Remontados will be displaced. Moreover, the construction of the dam can also endanger the ecosystem, habitats and natural wildlife living amidst the Sierra Madre which is located at the heart of the project. Protesters say that this project will only really benefit our water companies if pushed forward to fruition. However, entities among the water concessionaires say that actually, Chinese companies are being favored by the President to spearhead the Kaliwa Dam project, without supposedly undergoing any kind of bidding process.

Figure 7. Kaliwa Dam Project. Source: MWSS

Lastly and most importantly, Maynilad and Manila Water has long been criticized because they are water monopolies in their separate franchise areas. One can argue that the existence of two water companies in Metro Manila overall will foster competition – and thus will produce optimal rates and services. However, consumers in their respective East or West zones are still left with no choice or preference as to who will service them. Ultimately, we know what happens with monopolies: they are the product; they dictate the prices and everything that goes with it. How can the public truly ascertain that the water rates are fair and just? Even if for instance the government does open the field to other water players, do they really stand a chance?

Nationalizing the water concessions

The Advantages

When it comes to the nationalization of water and other public goods, it has seen growing support in advanced economies around the world. Democrats in the United States and Labor Party members in the United Kingdom have called for anti-capitalist approaches to public goods, whose private firms have earned profits at the expense of the public. There are greater calls for public goods to be returned to the government, or to face heavier regulation under privatization. In an economics reference website, British economics professor Geoff Riley (N.D.) argued that the immediate positive effect of water nationalization would be lower prices. The reality of the water industry is that it would be too difficult for several water companies to compete given the fixed underground waterworks and sewage system. Because of the infrastructure and investment requirements involved, water companies are natural monopolies that meet the economies of scale or providing water to everybody by themselves. Unfortunately, this also means that as monopolies, these water companies can control the water output and prices. Riley argued that a state-owned utility company would operate with public welfare in mind instead of profits. It could price water distribution rates closer to its marginal cost, which would reduce both marginal revenue and overall price level. Lower prices would encourage the income effect among households, who would have more excess income to save or spend on other goods. This is important to a country like the Philippines where household consumption accounts for more than 70% of its Gross Domestic Product (Trading Economics 2016). The government must enact policies to ensure that Filipino households continue to spend their disposable income and keep money circulating in the economy.

The government’s ability to spend on water distribution is another advantage of nationalization. One of the arguments against privatization is that firms justified charging higher prices because it required a high rate of return for working with the Philippine government. Lower Philippine economic standing when the concession agreements were entered into meant that these companies had to borrow at much higher interest rates, which it had to offset through revenues. Compared to private firms, the government can issue debt at relatively lower interest rates in order to fund continuous improvement of Manila’s water system (Riley N.D.).

Another major criticism against the private firms is that the profits are not being reinvested into the improvement of Manila’s water system. Manila Water in particular recorded Php 6.5 Billion and Php 6.8 Billion in net income in 2017 and 2018 respectively (Quismorio 2019). The concessionaires argue that those profits are the returns due to the investors who spent the same billions of pesos in the past to make the water concession agreement happen. However, politicians and leftist groups have exacerbated the crisis by making it an issue of capitalist greed versus government’s well intentions (CNN Philippines 2019).

The Disadvantages

Naturally, the main argument against water nationalization is that the Philippines had already done it before. The water concession agreement was entered into precisely because the Philippine government could not competently manage Manila’s water system (Santiago 2019). The current administration has called for re-nationalization but it has not shown any concrete plans on how it can improve on the concession model. The water shortage might just be aggravated even more and return to pre-water concession levels. President Duterte will be ending his term in 2022, which is coincidentally when the water concession will be ending. Calls for re-nationalization would be met with skepticism if there is no long-term plan for government to continue managing Manila’s water system after the Duterte administration. This indecisiveness would also affect the country’s reputation to foreign investors. It would give foreign investors the impression that the Philippines does not honor previously established contracts and agreements (Lee-Tan 2019).

According to a working paper by Ayn Torres and Dean Ronald Mendoza, PhD of the Ateneo School of Government, it is the MWSS that has failed to regulate the water rates and activities of the concessionaires. (Kho 2019). Yes, water distribution improved greatly but the prices being charged do not match the actual level of service rendered. It is the MWSS’ responsibility to ensure that Manila Water and Maynilad are continuously improving water distribution and looking for new water sources. Ironically, while the concession agreement states that it is the concessionaire’s responsibility to look for new water sources, MWSS’ website says that job belongs to the government.

Finally, several private sector groups have called for the water concession to be respected. The Joint Foreign Chambers of the Philippines & Philippine Business Groups and the Makati Business Club released statements that the concession has helped improve Manila’s water system in the last two decades (Kho 2019). There were barely 800,000 water service connections under nationalized water in 1994, compared to around 2.4 Million connections today. Non-revenue water has also improved from more than 60% to 12% for Manila Water and within the range of 27%-40% for Maynilad (Santiago 2019). It is highly possible that the private firms are correct that a combination of the climate crisis and overpopulation in Metro Manila have greatly strained the existing water sources. Even if the government intervenes, it would be forced to collect water from the same dams. Given the facts stated, the water concession has clearly improved access among Filipino households, but with scarce water resources and growing demand, the households may be forced to adjust.

Our water problems run deep

When it comes to the Philippines’s water situation, the obstacles that Manila Water and Maynilad face lie in: providing adequate and constant distribution of water and finding sustainable and feasible water sources and alternatives – all these things at aspired, “fair” rates to the eyes of consumers, but still at levels where they can be profitable. It is not as glamorous as people think. It is also a tough job, but that is what they signed up for, and thus, must continuously rise to the occasion.

We surmise that for the most part, large corporations, especially utility companies, will always be criticized on being supposedly greedy or having a disregard for public welfare when huge profits are dangled in their faces. However, today, and with the help of social media, information is more easily cascaded and accessible; such that, there is mounting pressure from the public for such corporations to be responsible and be guided by a moral compass. To be fair, what also often happens is that during times of problems like the said water interruptions or rate hikes, the public is quick to point fingers at our two concessionaires without fully understanding the underlying problems (political, environmental, social, economics– you name it). The multi-faceted issues are also further exacerbated by the current administration’s unreasonable antics.

Figure 8. Source: RigobertoTiglao.com

Liquidity Issues?

From the perspective of the consumer, yes, it is definitely arguable whether our current water rates are indeed “fair” and proportionate to their large revenues. Most, if not all Filipinos, will be quick to say that water rates are seem excessive. The provisions from the 1997 Water Concessions seemed to have favored the concessionaires, as they were made during a time when perhaps we can say the Philippine government was a little desperate. Today, what is the basis or reference really for water tariffs, if they are water monopolies in their own franchise area? This is an area where all stakeholders, the MWSS and Filipino citizens included, must be vigilant about. Yet to be realistic, rate hikes are pretty much expected over the years; it cannot be stopped, but it definitely can be mitigated and regulated.

Figure 9. Source: Pinoymoneytalk.com

Privatize or Nationalize?

This brings us now to the question: to privatize, or nationalize? To answer with a quote from a Forbes article by Worstall (2013), it was written, “Either of these could be great ideas or either of them could be terrible. At the end of the day, it all just comes down to the quality of the governance.” With this in mind, we can only truly conclude that the concrete advantages to maintain the privatization of water largely outweigh, what remains as mere potential opportunities to re-nationalize water, in the context of the Philippine landscape. The present water concessions are far from perfect, but the private sector will always outperform the Philippine government when it comes to such matters. Therefore, we do not agree with President Duterte’s stance to nationalize water in the Philippines, as this move will make the country truly vulnerable to a multitude of social and economic problems. In fact, his retorts and threats to cancel both Manila Water and Maynilad’s contracts are without basis, but only seems to fulfill a somewhat immature, personal vendetta. In effect, he is extorting these two conglomerates to give in to his whims. That is not democracy, and if they do bend over backwards, it will further undermine the country’s stability and integrity in the world arena and cause detrimental domino economic effects.

The government seems to be propagating this decision in the guise that it will keep water rates low and be seemingly beneficial to all. It is possible that the short-term effect is lower water rates; however, overtime, the whole country will just eventually experience again a shortage of water. Hence, nationalizing water is not sustainable, nor it is the answer. We cannot trust that this proposition of the Duterte administration has the best interest of the public in mind. As we have seen prior to the 1997 Water Concession agreements, government-controlled MWSS, engulfed in corruption and incompetency, were not able to adequately distribute water to Metro Manila. The Philippines will revert to the same circumstances – and worse, if water is to be nationalized.

Long-water: “Dr Michael Burry is focusing all his trading on one commodity: water," says a caption just before the credits roll in "The Big Short."

Written by:

Aguirre, Encarnacion, Qichao, Marcial, Sayson

Footnotes:

[1]Non-revenue water: Water that is lost due to leakages, illegal connections and used for public use (Taken from current MWSS Chief Regulator, Atty. Patrick Ty)

[2]The Water Crisis Act (WCA) gave the President the authority to privatize MWSS. This authority was strong because it did not prescribe any particular procedure for privatization. [The government] was free to create their own procedure” (Dumol 2000).

[3]Rate-rebasing or rate hikes refer to the basic charge only. If one were to “look at your water bill, there are other items that will also increase when the basic charge is raised. The environmental charge, for example, is 20% of the basic charge. Then, there is the foreign currency differential adjustment (FCDA), which accounts for the quarterly fluctuations in the foreign exchange rate (USD/Php). The FCDA is negative when the peso gains against the dollar and is positive when the peso weakens” (Padilla 2009)

[4]The 1997–98 Asian Financial Crisis began in Thailand and then quickly spread to neighboring economies. It began as a currency crisis when Bangkok unpegged the Thai baht from the U.S. dollar, setting off a series of currency devaluations and massive flights of capital… [The] crisis revealed the dangers of premature financial liberalization in the absence of established regulatory regimes, the inadequacy of exchange rate regimes, the problems with IMF prescriptions, and the general absence of social safety nets in East Asia.” (Britannica.com).

[5]The Best World (BW) Resources “stock price rose a staggering 18,025% in one year — from P0.80 in October 1998 to P145.00 in October 1999 — and its consequent crash that almost put the Philippine stock market into collapse. The PSE then stepped in and investigated the company. It uncovered several stock price manipulation strategies supposedly conducted by Dante Tan, a close ally of the President, and his cohorts” (PinoyMoneyTalk.com)

[6]Kaliwa Dam: Can provide “600 million-liters-a-day (MLD) capacity and its water supply tunnel has a 2,400-MLD capacity. It is expected to ease the demand on the Angat Dam, Manila’s sole water storage facility. When the project did not move forward by the time Aquino administration ended, the succeeding Duterte administration decided not to pursue the Japanese-proposed Kaliwa Low Dam plan and instead pursued a bigger, China-funded dam project.” The Kaliwa Dam project contains also various social, political and environmental issues.

List of References

Dumol, Mark. July 2000. The World Bank. The Manila Water Concession: A Key Government Official’s Diary of the World’s Largest Water Privatization.

Wu, Xun, Nepomoceno, A. (2008). Urban Studies. A Tale of Two Concessionaires: A Natural Experiment of Water Privatisation in Metro Manila. 45 (1): 207–229. doi:10.1177/0042098007085108., p. 212-217

Chia, et al. 07 May 2007. Water Privatization in Manila, Philippines Should Water be Privatized? A Tale of Two Water Concessions in Manila

Ba, Alice. ENCYCLOPEDIA BRITANNICA – The Asian Financial Crisis. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/event/Asian-financial-crisis

Rivas, Ralf. 06 December 2019. RAPPLER – Public Interest, Private Hands: How Manila Water, Maynila got the deal. Retrieved from https://www.rappler.com/business/246526-how-manila-water-maynilad-got-concession-agreements

Rivas, Ralf. 17 March 2019. RAPPLER - Manila Water’s supply crisis: What we know so far. Retrieved from https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/iq/225953-what-we-know-explanation-manila-water-supply-crisis

Romero, Alexis. 04 December 2019. THE PHILIPPINE STAR – Duterte slams water concessionaires. Retrieved from https://www.philstar.com/headlines/2019/12/04/1974134/duterte-slams-water-concessionaires

Philippine Stock Exchange (PSE) Edge, MWC Company Disclosures. Retrieved from https://edge.pse.com.ph/companyDisclosures/form.do?cmpy_id=270

05 December 2019. THE BUSINESS MIRROR – Manila Water explains how arbitral ruling came about. Retrieved from https://businessmirror.com.ph/2019/12/05/manila-water-explains-how-arbitral-ruling-came-about/

Valente, Catherine. 21 December 2019. THE MANILA TIMES – MWSS, water firms to ‘sanitize’ contract. Retrieved from https://www.manilatimes.net/2019/12/21/news/headlines/mwss-water-firms-to-sanitize-contract/666095/

Maderazo, Jake. 10 December 2019. THE PHILIPPINE DAILY INQUIRER – Provisions of water agreements raise a lot of issues. Retrieved from https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1199870/provisions-of-water-concession-agreements-raise-a-lot-of-issues

Yu, Sandra O. (2002). Infrastructure Development and the Informal Sector in the Philippines. International Labour Organization.

Mitlin, Diana. (2002). Competition, Regulation and the Urban Poor: A Case Study of Water. Regulation, Competition and Development: Setting a New Agenda. Centre on Regulation and Competition, CRC International Workshop, 4-6 September 2002, Crawford House Lecture Theatre, University of Manchester, 39pp.

McIntosh, Arthur C.; Yñiguez, Cesar E. (October 1997). Second Water Utilities Data Book – Asian and Pacific Region (PDF). Asian Development Bank. pp. 4–7. ISBN 978-971-561-125-1. Retrieved 2008-04-25.

Freedom from Debt Coalition (March 2009). "Recalibrating the Meter". pp. 1–4. Archived from the original on 2013-04-16. Retrieved 18 June2012.

Marin, Philippe: Public-Private Partnerships for Urban Water Utilities, World Bank, 2009, p. 56f.

Grefe, Christian. 21 August 2003. Wie das Wasser nach Happyland kam (How the water came to Happyland), Die Zeit, Germany.

Manila Water. "Wastewater Management". Retrieved 7 July 2012.

Regulation and corporate innovation: The case of Manila Water, by Perry Rivera, in: Transforming the world of water, Global Water Summit 2010, Presented by Global Water Intelligence and the International Desalination Association

ABS-CBNews.com. 9 September 2011. "Manila Water wins Asian Human Capital award". Retrieved 7 July 2012.

Gomez, Yolanda. Providing Pro-Poor Water Services in Urban Areas through Multi-Partnership:The Streams of Knowledge Experience. World Water Week Abstract Volume. pp. 279–280.

CNN Philippines (2019, March 17). Senate hopefuls urge government to take back control of the country’s water resources. Retrieved January 27, 2020, from https://cnnphilippines.com/news/2019/3/17/Water-privatization-Manila-Water-Maynilad.html

Kho, G. (2019, August 28). The GUIDON – Nationalized vs. private: Supplying Manila’s water. Retrieved January 27, 2020, from https://www.theguidon.com/1112/main/2019/08/nationalized-vs-private-supplying-manilas-water/

Lee-Tan, A. (2019, December 9). Philippine Daily Inquirer – Why govt shouldn’t nationalize water concessions. Retrieved January 27, 2020, from https://business.inquirer.net/285044/why-govt-shouldnt-nationalize-water-concessions

Quismorio, E. (2019, June 24). Manila Bulletin – Privatization blamed for water supply woes; gov’t urged to take over water utilities. Retrieved January 27, 2020, from https://news.mb.com.ph/2019/06/24/privatization-blamed-for-water-supply-woes-govt-urged-to-take-over-water-utilities/

Riley, G. (N.D.). Economics – Water Nationalisation. Retrieved January 27, 2020, from https://www.tutor2u.net/economics/reference/exam-answer-water-nationalisation

Santiago, E. (2019, December 25). The Philippine Star – Commentary: Water distribution from public to private sector and back? Retrieved January 27, 2020, from https://www.philstar.com/other-sections/news-feature/2019/12/25/1979679/commentary-water-distribution-public-private-sector-and-back

Trading Economics. (2016). Philippines – Household Final Consumption Expenditure. Retrieved January 27, 2020, from https://tradingeconomics.com/philippines/household-final-consumption-expenditure-etc-percent-of-gdp-wb-data.html

20 January 2009. The Philippine peso, from 1950 to 2009. Retrieved from http://mpgonz.blogspot.com/2009/01/philippine-peso-from-1950-to-2009.html

Chiplunkar, Anand et al. May 2008. Asian Development Bank. Maynilad on the mend: Rebidding Process infuses New Life to a struggling concessionaire.

Carson, Michael and John Clark. 22 November 2013. Federal Reserve History. Asian Financial crisis. Retrieved from https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/asian_financial_crisis

Padilla, Arnold (2012). A Radical’s Nut: Notes on Philippine economy and politics. Retrieved from https://arnoldpadilla.com/2012/12/20/ph-water-rates-among-asias-highest/water-rate-hike-gmanetwork-com/#main

http://mwss.gov.ph/projects/new-centennial-water-source-kaliwa-dam-project/

https://www.rappler.com/thought-leaders/243793-opinion-the-illegal-and-immoral-kaliwa-dam-ecc

http://www.chanrobles.com/republicactno8041.htm#.Xi-M9c4zaUk

https://ppp.worldbank.org/public-private-partnership/library/manila-water-concession-agreement-for-water-and-sanitation-services

http://ro.mwss.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/Manila-Water-Term-Extension-Agreement-with-Annexes.pdf

https://cnnphilippines.com/news/2019/12/13/manila-water-maynilad-contract-extension-still-stands.html

0 notes